3. Staffing Supply Chains

3.2.2 Evaluating Candidate Capabilities

3.3 Global Staffing Considerations

3.3.1 Global Hiring Philosophy

3.4.1 Staffing Retention Sabbaticals

3.4.3 Human Resource Succession Program

3.4.4 Developing Supply Chain Procurement Teams

Terms

American Production and Inventory Control Society (APICS)

Career-path mapping

Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP)

Cross-functional succession

Ethnocentric

Geocentric

Global oriented

Home country national

Host country national

Institute of Supply Management (ISM)

Polycentric

Regiocentric

Third-country national

Vice president of operations (COO)

3.1. Prerequisite Material

This section is chiefly to acquaint less-experienced students of supply chain management with basic and elemental content and terminology. Experienced supply chain executives and managers might be tempted to skip this section in chapters where it is included, but they might instead want to use it as a review of basic concepts and terminology.

Jobs in supply chain management entail a wide spectrum of tasks and assignments. Staffing supply chain jobs requires finding talented people who will bring to the positions the right competencies and skills to overcome diverse challenges the organizations face in the global economy. Some of these competencies are listed in Table 3.1. There are, of course, many more, but these illustrate how staffing supply chain managers seek special individuals who are competent in many dimensions of social behavior.

Table 3.1. Staffing Competencies

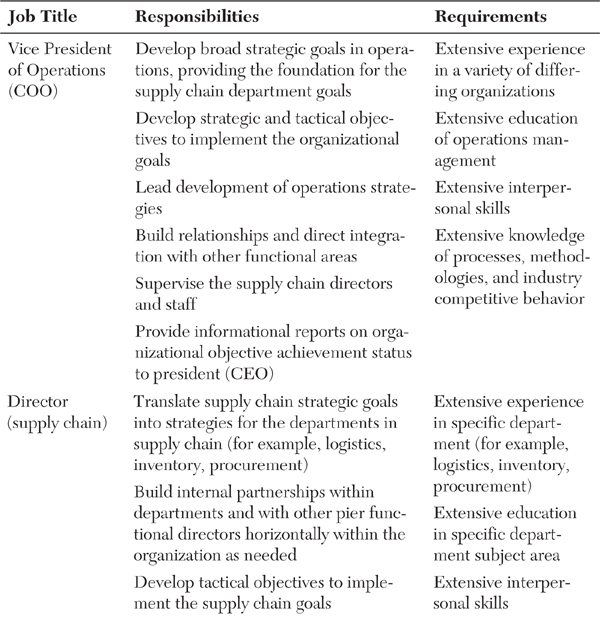

In any organization with a supply chain, basic jobs must be performed. Although titles may vary considerably from organization to organization, basic titles, responsibilities, and requirements are fairly standard for all organizations. To help conceptualize these positions, Table 3.2 describes a few of these positions.

Table 3.2. Types of Staffing Positions, Responsibilities and Requirements

Some of the best sources for recruiting, staffing and education are provided by professional supply chain organizations. Three major professional organizations that provide education and employment support in the area of supply chain management are the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) (www.ism.ws/), American Production and Inventory Control Society (APICS) (www.apics.org/default.htm), and the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) (http://cscmp.org/). Collectively, they represent tens of thousands of supply chain professionals and educators offering certifications in supply chain management, including the content and requirements for staffing activities needed.

3.2. Staffing Supply Chains

3.2.1. Recruiting Strategies

Entry-level positions today should require a college degree in supply chain management. Recruiting these personnel involves establishing a college and university campus interviewing program. For organizations interested in recruiting entry-level employees, this might involve traveling to universities and working with student job placement departments or giving workshops on career opportunities where allowed by the campus. Developing a general career roadmap brochure explaining to the student what a career in supply chain management is about, what positions it can lead to, and how they can benefit is one useful tactic of the staffing strategy.

A more aggressive strategy is to build partnerships with specific universities where the supply chain organization can offer potential candidate students internships before they graduate. These internships can be either paid or not paid, and will offer the student an opportunity to gain experience in a real supply chain organization. They will also allow the firm to evaluate the student’s potential for a future job.

Entry-level talent can also be located and recruited online with the variety of social networks such as Facebook or Twitter that allow for personal information to be made public. These are actually valuable sources of information. Much of what is available through these social networks is information that could not be requested under governmental laws restricting privacy.

For midlevel managers, recruiting can be efficiently performed with the help of major supply chain professional organizations. Major supply chain professional organizations, such as the ISM, CSCMP, and APICS, provide forums for job placement. They are general markets that act as conduits of candidate information and availability. All three organizations are actively involved in job placement, helping both the employee and employer to connect.

The midlevel and upper-level positions require more experience, which is a key factor in recruiting these employees. For supply chain executives within a firm, establishing a network of peer professionals that share information about employees can be a valuable and inexpensive way to identify candidates. Personal social networking can help find experienced personnel for midlevel and upper-level senior positions in supply chains. It goes without saying that job opportunities are still a function of “who you know” in an industry. A critical success factor (CSF) is to carefully review references (for example, who they are, what they say or not about criteria important to hiring firm). This information should be followed by interviews at all levels of responsibility in a department, functional area, and organization-wide. Each level of interviewers within an organization can bring unique perspectives and understanding to the recruitment process and selection.

Other recruiting for midlevel or upper-level senior supply chain management positions can be undertaken by professional recruiting organizations. Some of these include third-party recruiters or executive search firms. A third-party recruiter serves as an employment agency. It acts as an independent contact between the client company and the candidates. These recruiters tend to specialize in permanent, full-time, direct-hire positions or contract positions.

For supply chain executives, such as at the vice president level, executive search firms specialize in recruiting executive personnel. Executive search professionals typically have a wide range of personal contacts in the industry or field of specialty. They are knowledgeable in specific areas (for example, focusing research expertise in a limited field), such as supply chain management. Executive search professionals are typically involved in conducting detailed interviews and presenting candidates to clients selectively. They usually have long-lasting relationships with clients.

3.2.2. Evaluating Candidate Capabilities

Although certifications and degrees can be viewed as a general statement of the capabilities of personnel, there may be unique skills and competencies desired of the supply chain staff based on departmental needs. For example, being able to negotiate may be important for procurement employees, and being able to evaluate personnel is always important for candidate managers. A particular company’s culture and philosophy of negotiating or evaluating personnel might require unique skills for new hires. To measure this, firms undertake skill assessments and diagnostic analyses to determine whether new hires possess the skills and competencies needed.

Flynn (2008, pp. 239–240) recommends a gap analysis to determine if employees need training for an additional or new skill or competency. Gap analysis is a tool that uses a survey method to measure the level of skills and competencies possessed by employees that are then compared to desired levels. Basically, a set of measures are taken of a desired set of skills. For supply chain personnel, Flynn (2008, p. 240) suggests this set of skills might include managerial skills (for example, project management, time management), interpersonal skills (for example, cross-culture communications, business ethics), analytical skills (for example, accounting, cost and price analysis), and commercial skills (for example, risk management, quality). A survey is given to new or existing employees that measures skill level by numeric responses (for example, 1 to 5 scale) to questions designed to reveal capabilities. These measures are then compared with a set developed by existing managers in the firm who excel at jobs in each area. The latter measures are the standard for comparison. The gap between the employee measures and the standard set from the managers reveals (if it exists) gaps between the employee’s actual score and the manager’s desired score and helps to specifically pinpoint the need for further training and competency development.

3.2.3. Retaining Employees

There are many CSFs that cause an employee to stay with or be retained by a firm. If not considered, CSFs can also become reasons why employees leave organizations. These CSFs include job satisfaction, compensation, work environment, and career succession opportunities.

Job satisfaction is the perception by employees of how fulfilling the tasks they perform are to themselves and their organizations. It is viewed as an emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job and attitudes toward the job. The more satisfied an employee is with their job, the more likely they are to be to want to keep their job.

Job satisfaction can be measured in many ways. The most common method for collecting data about job satisfaction is based on a numeric scale (for example, from 1, which represents agreement, to 7, which represents no agreement) with survey questions about job content, like “I am generally a happy person.” A more standardized instrument for use in any firm is the job descriptive index (JDI), which has a specific questionnaire for measuring satisfaction along five dimensions: pay, promotions and promotion opportunities, coworkers, supervision, and the work itself. The scale used in this instrument has participants answer either yes, no, or can’t decide (indicated by ?) in response to whether given statements accurately describe how they feel about the job.

Compensation and benefits are both very important in staffing retention. Compensation is the pay package of salary and benefits given to an employee for performing jobs. Salary is often a determiner of retention if it is out of line with peers or the market salary for a particular position. Benefits can be viewed as a part of an organization’s compensation program. Benefits are where firms can be creative to encourage retention. Beyond providing compensation, firms can also include healthcare benefits, reimbursement for education, paid vacations, free travel benefits (for example, taking spouses on trips), flexible work hours, time off, and sabbaticals. Flexibility in structuring benefits can encourage retention.

The work environment is more than the physical locations where the employees work; it is also the psychological environment created by the organizations. Many supply chain managers are traveling more than working onsite in an office. The psychological environment is created by organization policies (avoiding rigidity in policies but seeking flexibility to seize opportunities), by upper management through their style of leadership (avoiding dictatorial styles but seeking styles that are supportive and nurturing), and by staff (seeking optimistic, energetic and communicative staffers who encourage the same from employee). Work environments that encourage a positive attitude about job content will be better able to retain like-minded people.

For many supply chain executives, career succession is as important as compensation or any other job-retention CSF. Knowing that advancement is possible in the future because of a clearly defined career succession program will encourage retention. Also, the knowledge of what career succession will bring in terms of future job satisfaction, compensation, and work environment will help foster an environment that encourages retention of employees. Everyone needs the hope that tomorrow will bring a brighter day, and for career-minded supply chain managers, hoping for better times tomorrow is what helps get them through rough times today. Mapping out a possible career path for employees and communicating it to them helps establish a personal interest perception (for the organization to the employee) that can be a strong motivator to stay with a firm. It helps them look ahead to opportunities and motivates them to want to stay in their jobs.

3.2.4. Terminating Employees

People who violate organization standards or fail to meet performance expectations may need to be terminated. Other reasons might include insubordination, theft, substance abuse, or physical violence. Ideally, the organization should have a formal process to exercise when a termination becomes necessary. The process has to comply with local, state, and federal laws. In foreign countries, the process may be easier or more complex, but regardless, the process of termination should be viewed as a serious event requiring care by and sensitivity to all involved.

In situations where large numbers of employees have lost jobs because tasks were outsourced to other organizations, many firms can negotiate with the outsourcer to hire the firm’s employees to work for the outsourcer. In other situations, hiring freezes and retirements might prevent the need for major terminations when plant closings occur due to shifts in demand.

Whenever employees are terminated or let go, the organization should seek to undertake exit interviews. An exit interview is an interview conducted of the departing employee by the firm that is letting them go. Human resource staff members generally conducted these interviews. They seek to determine useful, perceptual, or factual information about why the employee is leaving the firm (either being fired or just leaving). Exit interviews can be conducted via paper and pencil forms, telephone interviews, in-person meetings, or online. Some employers choose to use a third-party human resource organization to conduct the interviews and provide feedback.

3.3. Global Staffing Considerations

3.3.1. Global Hiring Philosophy

In a very real sense, all supply chains today are global in scope, and staffing them offers managers incredible challenges and opportunities. One the first steps in staffing a global operation is to determine the type of individual a firm wants to recruit for global operations. There are different ways to categorize potential employees. One way is to look at candidates in the context of a firm’s hiring philosophy. There are four different categories of potential employees to staff global operations, based on a firm’s hiring philosophy: home country national, host country national, third-country national, and global oriented (see Table 3.3). The selection of a hiring philosophy represents a general guideline that can be used for all hires by a global firm regardless of the location, or it can be exercised based on the needs of the individual firm, the type of job, and willingness to trust the employees. Many factors can guide a global hiring philosophy selection, such as a firm’s global strategies. For example, suppose that a U.S. firm has a low-cost objective for a new production facility that is being located in foreign country. Although most any of the four philosophies will apply, there may be some startup advantages of hiring a host country national or polycentric philosophy due to employees being familiar with the host country.

Table 3.3. Categories of Global Employees Based on a Firm’s Hiring Philosophy

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans (1998), pp. 37–38.

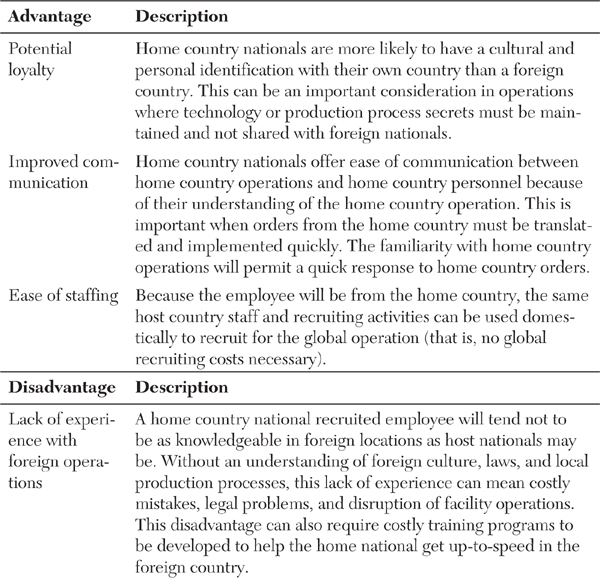

Why one type of employee would be selected over another rests largely in the advantages and disadvantages each hiring philosophy offers. Some of the advantages and disadvantages are listed for the home country national employee ethnocentric philosophy in Table 3.4, the host country national employee polycentric philosophy in Table 3.5, the third-country national regiocentric philosophy in Table 3.6, and the global-oriented geocentric philosophy in Table 3.7. In combination with other personnel information (for example, employee capabilities) and the organization needs, these philosophies can help in guiding a global hiring decision.

Table 3.4. Advantages and Disadvantages of a Home Country National Ethnocentric Hiring Philosophy

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans (1998), pp. 39–41.

Table 3.5. Advantages and Disadvantages of a Host Country National Employee Polycentric Hiring Philosophy

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans (1998), p. 41.

Table 3.6. Advantages and Disadvantages of a Third-Country National Regiocentric Hiring Philosophy

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans (1998), p. 42.

Table 3.7. Advantages and Disadvantages of a Global-Oriented Geocentric Hiring Philosophy

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans (1998), pp. 43–44.

The balancing of the advantages and disadvantages listed for differing hiring philosophies in Tables 3.4 to 3.7 is a difficult task. Fortunately, it can be made easier by choosing the global-oriented philosophy for recruitment and selection. The global-oriented philosophy tends to have all the advantages of other recruitment and selection philosophies with little of the disadvantages. It is also a philosophy characteristic of current top supply chain talent (Slone et al., 2010, pp. 63–68).

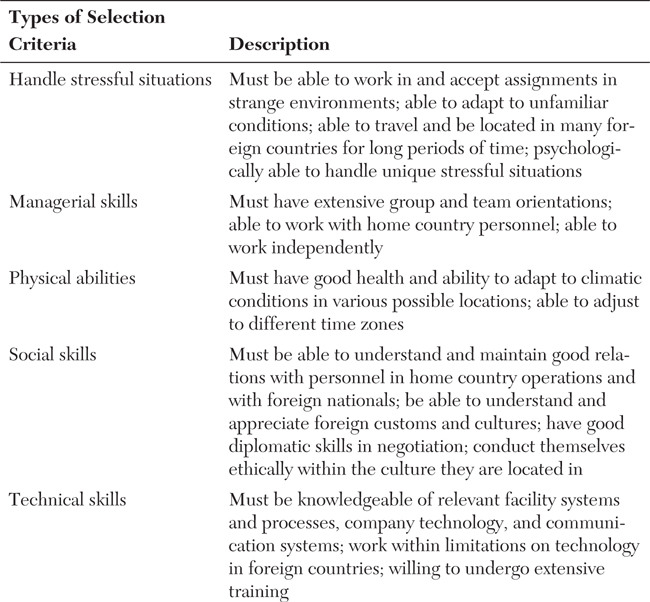

3.3.2. Employee Selection

Obtaining the right global-oriented employee, developing them, and retaining them are all important factors in staffing global supply chains. Selection of global-oriented employees should start with an organization-specific set of criteria that can act to guide the selection process. Although the uniqueness of an organization makes the subject too voluminous to cover here, general guidelines can be suggested (see Table 3.8). While skills and abilities are important, being able to handle the stress in a supply chain management position in a foreign country is clearly a CSF for any global-oriented employee. The stress capacity of an employee, as well as the skills and abilities, should be measured, documented, and weighed in the analysis as critical inputs to the selection decision.

Table 3.8. Global-Oriented Selection Criteria

Source: Adapted from Table 3.3 in Schniederjans (1998), p. 46.

3.3.3. Employee Training

For important hires or individuals who are transferred from other countries and may lack a particular set of skills, training is an important part of the employee development program. Training can be used to determine and confirm whether a person has the ability to run global operations. Also, supply chain executives should be aware that a global operation using expatriates or home country nationals can expect to have substantially larger budgets for training than a typical domestic organization. Some firms try to keep training costs down by using specialized firms that focus on training specific skill sets. For example, language alone is a most important skill for expatriates to possess to be successful in jobs and adapt to the host country. Some global firms utilize private tutoring, such as Berlitz training classes (www.berlitz.us/). Another strategy is to use older employees and retirees to help educate and orient foreign employees in host country languages and share cultural experiences.

One of the most important types of training for anyone working in a global operation is intercultural training. Intercultural training is an educational program that can help impart knowledge to employees to prepare them to be sensitive to differing cultures. Intercultural training provides useful culture, customs, and role expectations for employees and their relationships in business settings. As a form of sensitivity training, the training begins with a self-awareness step where global managers learn to recognize their own personal assumptions and values and how they might impact or alter their understanding of differing cultures. Once self-awareness is established, training usually focuses on developing an appreciation of multiple perspectives, allowing employees to understand points of view from other cultures. Table 3.9 describes some other components of intercultural training. The implementation of this training often requires an investment in specialists, consultants, and educators with experience in foreign cultures.

Table 3.9. Intercultural Training Program Elements

Source: Adapted from Table 3.4 in Schniederjans (1998), p. 47.

3.3.4. Employee Compensation

Global compensation requires consideration of pay-related factors impacting what employees receive in remuneration. Compensation can include the consideration of factors related to an employee’s base salary, taxation, benefits and allowances, and pension.

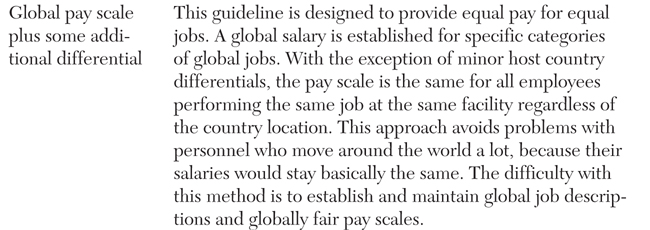

The amount of base salary necessary to pay a global employee should be based at least in part on the following guidelines: (1) a rate consistent and fair in treatment of all employees regardless of position in the organization structure, (2) a rate that will attract and retain employees regardless of the global location of employment or the nature of the jobs, (3) a rate that will motivate employees to excel, and (4) one that establishes a system of pay facilitating movement within the global network. Table 3.10 describes additional guidelines.

Table 3.10. Global Compensation Guidelines

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans (1998), p. 48.

One problem with all these guidelines is the rate of exchange impact that salaries experience in a global context. Some employees work in one country while their families are located in another country. If the rate of exchange does not favor a particular family located in another country, the employee will view this as a reduction in pay (and the appropriate motivational discouragement that comes from this reduction). Adequate adjustments to compensate for any exchange-rate penalties should always be considered when setting up global compensation programs. This adjustment is particularly important when country currencies are experiencing rapid valuation fluctuations.

Taxation is also an important consideration of any compensation program. Many expatriate employees are doubly taxed (that is, taxed by their home country and the host country). While in the United States, Section 911 of the U.S. Federal Government Internal Revenue Service Code allows a substantial deduction to mitigate the impact of double taxation. Most other nations tax part or all of their foreign-employed nationals’ income. To help compensate for this double taxation where it is enforced, additional base salary or nontaxable benefits can be included in a compensation program.

3.3.5. Benefits and Allowances

Benefits and allowances (financial and nonfinancial) are important considerations in employee compensation programs. Benefits can include such items as medical and dental insurance, social security payments, pension plans, time off, membership fees in professional organizations, sabbaticals, vacation, sick leave, life insurance, and so on. Allowances can be financial equivalents to the benefits, as well, and they can be unique, such as a cost-of-living allowance or relocation allowance for shipping, moving, storage, or temporary living expenses for transferring employees. When establishing global benefits and allowances, supply chain managers should consider many factors, including the following:

• The benefits and allowances that should be included in a global benefits program

• Whether the home country employees and global employees should receive the same benefits and allowances

• Whether the host country, third-country, or global-oriented employees should receive the same social security payments as in the home country

• Whether there should be differentials in the benefits and allowances for employees in the global operations that are made up by salary increases

• What considerations should be made to address benefits and allowance limitations and requirements placed on the firm by non-home-country governments

Given the size and complexity of pension programs, which are sometimes mandated by governments, great care should be given to the management of any global pension plan. An explicit policy statement should be established documenting how pensions are managed and who is responsible for them. When developing a policy, an organization must address the following issues:

• Calculating the costs of global pension obligations and how they are financed

• Controls, reports, and approval procedures relating to pension planning implemented by the home country office or host country office managers

• What the home company’s responsibility should be with regard to investing pension assets, and which executives from the finance department of a regional organization or national office control such decisions

• Guidelines for the organization’s investment philosophy regarding pension funds and who must approve them

• Local, regional, state, and federal government law compliance

• Who is responsible for monitoring and reporting the performance of the pension fund investments in a timely manner

Creative employment benefit arrangements can be used to recruit host country national employees by offering them opportunities to work in their country of origin for a period and then return to a foreign country of choice. For example, Jennings (2011) reports that recruiting Chinese host country national employees can be difficult when they have been educated in the United States. Some Chinese nationals would like to get a job in the United States, but prospective companies need host country national employees for the advantages they offer in dealing with issues regarding operations facilities in China. One strategy is to offer these employees an attractive expatriate financial plan, which includes a future opportunity to return to the United States. Jennings suggests this is a key factor for having a permanent Chinese native working for U.S. firms in their offshore U.S. operations in China.

3.4. Other Staffing Topics

3.4.1. Staffing Retention Sabbaticals

When factoring in required travel, psychological pressure of constantly meeting deadlines, global competition, and many other typical tasks and considerations, few jobs are as stressful and demanding as those in supply chain management. For organizations, the best employees are ones who work the hardest (and smartest). As a result, many supply chain executives can become burned out mentally and physically well before they retire. For organizations that want to keep these talented staffers, they need to consider developing a sabbatical program. A sabbatical program allows employees a leave of absence from their jobs (Allen, 2011). It can be paid or unpaid time off from what they do on a regular basis.

Like an added vacation (whether paid or not), the sabbatical is a way of disengaging the employee from the job and the accompanying stress for a period of time. Unlike a regular vacation that a family may fill with work or one where the supply chain manager is still on call, a sabbatical is a means for really getting away from the work environment.

Some companies are not well suited for sabbatical programs because of the continuous nature of demands on executives whose roles are so significant that they cannot be spared for sabbaticals of any kind. Those who might be interested in implementing a sabbatical program might consider the steps in Table 3.11.

Table 3.11. A Procedure for Implementing a Sabbatical Program

Source: Adapted from Allen (2011), p. 44.

3.4.2. Lateral Staffing Moves

Due to downturns in the economies of world, high-performing supply chain executives have found moving laterally to another internal functional area in an organization or laterally externally to a competitor’s organization is a means to grow in experience and knowledge. Tuel (2011) suggests the best supply executives are those who have broad experience and knowledge in multiple functions of an organization and in multiple organizations. For example, an executive who has worked in both marketing and operations is likely to be more efficient in integrating those two functional areas than a less-experienced manager who only has marketing or operations experience.

Tuel suggests several beneficial ways to make the best of a lateral move, which also serves the organization. One way is to develop relationships and network with leaders of other internal supply chain functions to communicate a desire to learn. This will enhance organizational learning and knowledge sharing for both the employees who move laterally and those who are working with the new employee.

Lateral moves should be encouraged in organizations where upward mobility is limited or where highly successful employees might be restless and look to move elsewhere. Lateral moves help to cross-train executives and other staffers, making them better able to understand the organization and integrating their job with others for the benefit of the organization

3.4.3. Human Resource Succession Program

Its not enough to attract talented supply chain leaders. They must be retained. High-performing supply chain managers are assets to the organizations in which they work. Like talented sports figures, top-performing supply chain managers are highly mobile and represent a scarce resource that can easily be lost to competitive supply chain organizations that offer greater opportunities for advancement.

A successful strategy for retaining supply chain personnel involves establishing a succession program. A succession program uses a variety of methods for identifying and developing talented supply chain managers (Fulmer and Bleak, 2011). By identifying talents and career preferences of supply chain managers, a succession plan allows the firm to match them to future jobs within the organization. This best practices program helps firms track their employees own successes. It also helps the firm identify developmental opportunities, placing the right people in those positions, and identifying future shortages of talent.

Successful succession programs usually involve quantitative and qualitative measures that seek to determine talent dimensions of a manager’s ability to lead an organization. Data for these measures can come from a broad range of raters, who are well trained in communicating such data. The raters might include administration staff, internal and external customers, support staff, superiors, and subordinates. A suggested method, 360-degree input (that is, input provided by a variety of sources throughout an organization, including personnel who deal regularly with the employee and not just the immediate superior, but staff, subordinates, peers, and so on) provides a comprehensive collection of information that better characterizes the employee’s abilities. Quantitative measures might include how well the manager meets goals important to the organization (for example, ethnic or gender diversity goals), retention and attrition rates, and job-performance evaluations. Qualitative measures might be based on a participant’s transition experience in a new role, how well he or she was prepared, and reasons for attrition.

Long-term success in succession programs requires continual organizational commitment and continuous improvement according to Fulmer and Bleak (2011). Table 3.12 describes several characteristics of successful succession programs.

Table 3.12. Successful Succession Characteristics

3.4.4. Developing Supply Chain Procurement Teams

Creating, developing, and nurturing teams for projects and programs are important staffing functions for any organization. Building a supply chain procurement team, for example, can be a challenge for supply chain executives. Trowbridge (2011) reports there are fundamental CSFs that can lead to extraordinary results (see Table 3.13). The continuous application of the CSFs in Table 3.13 can result in outstanding procurement teams better trained, motivated, and empowered to do their jobs.

One final aspect of team building should be suggested. Some employees may be productive individually but are not team oriented. Some specialized team training might be able to move them toward more of a team work ethic. However, it might be better to remove such employees from team projects. Effective supply chain management leadership requires a willingness to add and delete personnel to maximize the organization’s outcomes.

3.5. What’s Next?

The daunting task of training supply chain and manufacturing personnel does not appear to be getting easier. In fact, the future trends suggest a major effort is needed to bring prospective employees “up-to-speed” (Gold, 2012). The Manufacturing Institute (www.themanufacturinginstitute.org/) survey on skills gaps shows more than 80% of manufacturers say they are experiencing a moderate to severe shortage of skilled production workers. These shortages are present in the supply chain area as well. In a study by KPMG International (“Global Manufacturing...,” 2011), the availability of skilled workers now tops the list of human resource concerns in emerging markets.

To help fill the gap between the desire to staff supply chains with capable people and the reality of shortages, many firms have chosen to enhance personnel capabilities they have and to develop strong training programs for new hires. The Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation (MAPI) (www.mapi.net/) surveyed top human resource executives in manufacturing (Gold, 2012). The survey results revealed firms were planning to offer substantial in-house training. Many are expanding and diversifying their educational offerings. Some of the observed and recommended educational strategies to deal with shortages are as follows:

• Training entry-level and intermediate/advanced employees with in-person classes taught by internal and outside instructors

• Training programs giving more emphasis to enhancing team-building skills and the capacity to think through the logic of a process

• Training and development programs offered to engineers so that they can understand the needs of customers

• Financial support for employees to obtain multiple course certificates and certifications at technical schools or community colleges

• Financial support for Bachelor’s degree programs for production employees