The standard commodity

An inevitable measure of value

Giorgio Gilibert*

The discovery of a right measure puts down rebellion and favours harmony. Unfairness disappears and justice prevails. With a right measure, men will agree about their mutual obligations.

(Archytas of Tarentum)

And Cain invented weight and measure, and transformed innocent and generous men into cunning and selfish beings, corrupting their lives.

(Flavius Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae)

The ‘invariable standard of value’ is a theme that Piero Sraffa considered of central importance. Indeed, he dedicated more than half of the first part of his book to this. And yet — almost fifty years after the book’s publication — there is no general consensus among scholars regarding the significance and the analytical utility of the standard commodity.

Perhaps this unsettledness can be partly attributed to a peculiar form of strabismus among scholars: much more attention has been paid to the physical nature of this composite commodity than to the fundamental analytical role that it was called to play and that is its obvious raison d’être. This fact, combined with a common disregard for the Sraffian claim not to assume constant returns to scale, provoked a trivial, but widespread, misunderstanding: that this ‘purely auxiliary construction’ (Sraffa, 1960, Section 43) has anything to do with the physical structure that, in linear models, corresponds to the maximum growth rate ‘for the whole economy’ (v. Neumann, 1937).

I propose here to revisit the whole topic in the simplest meaningful setting, in order to avoid as far as possible unnecessary technicalities, and to focus attention on the conceptual issues.

Suppose that only two commodities are produced: x and y (wheat and iron), and that they are produced by two different industries. The two industries are not self-sufficient, i.e. they depend on mutual exchange for their survival, and an exchange-value, or relative price, is necessary.

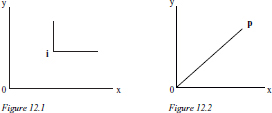

Any amount of the two commodities can be represented as a point in the commodity space xy. In particular, we can consider the social input point: i.

If the corresponding social gross output point lies in the quadrant N-E of i, the economic system is viable with a surplus. If the social product does not lie in the quadrant, the system cannot survive. Eventually, if the social product coincides exactly with i (Figure 12.1), we find ourselves in that ‘simple society which produces just enough to maintain itself (Sraffa, 1960, Section 1).

The price p can be interpreted as a conversion rate, which transforms iron quantities into their wheat-equivalents (and vice versa) and it can be visualized as the slope of an oblique line passing through the origin (Figure 12.2).

The simplest formula expressing the relationship between price and production cost is: Price ≥ production costs. This formula is not a result of a scientific analysis of the phenomena of economic life, but a simple statement of the self-evident fact that production cannot continue (at least for any appreciable length of time) if the price of the product does not cover the cost incurred. (Dmitriev, 1974 [1904])

This price, which covers production costs, may be called ‘reproduction price’. It can easily be shown that, if the economic system is not viable (the output point lying outside the N-E quadrant), there is no reproduction price line passing in the positive quadrant. If the output and the input points coincide, there is only one such line. If the economy is viable with a surplus, a whole set of reproduction prices spans out. The amplitude of the fan is intuitively related to the productivity of the system (Figure 12.3).

Figure 12.3

At the end of the last century, many continental European economists were puzzled by the following problem: does a reproduction price that grants a common profit rate on advanced capital to industries always exist? And can we ‘express this process in an exact mathematical formula which will allow us to determine the profit rate deriving from this adjustment’? (Conigliani, 1900). A first positive answer was given by Dr Mühlpfordt in 1895.

This price, which covers production costs and grants a uniform profit rate, has often been called ‘production price’. It can be shown that (i) to any viable economic system there corresponds only one production price, and that (ii) the corresponding common profit rate is higher the bigger the surplus produced (valued at the production price) and the wider the reproduction prices fan.

The rate of profits can therefore be considered as the strategic variable that summarizes, in one single number, the ‘productivity’ of the whole economic system.

Figure 12.4

What about the measure of value? In order to determine the profit rate, we have to express the price in terms of wheat, or of iron (or indeed of any basket of the two commodities). This means that we choose to align our accounts horizontally in terms of wheat-equivalent quantities, or vertically in terms of iron-equivalent quantities. Or indeed along any oblique line in terms of some basket of the two commodities. However, the choice of the standard, which of course affects the price, does not affect the rate of profits, which is a pure number (Figure 12.4, where the symbols have their usual meaning and πx is the profit in the corn industry). Therefore, at this stage of the analysis, we can consider the standard chosen as analytically insignificant: ‘an arbitrarily chosen commodity’ (Sraffa, 1960, Section 3, 12).

Then, Sraffa explores the properties of a new type of price: a price that covers costs and grants a uniform profit rate to the capital advanced and a uniform net wage rate to the workers employed. Let us label it as Sraffa price. (A similar problem was studied in the 1930s by the Guillaume brothers, but without particular insight.)

The wage, like the price, must be expressed in terms of a standard, i.e. as a purchasing power over the commodity chosen as standard.

If we consider the wage as the independent variable, the choice of the standard becomes obviously significant. The standard chosen should coincide with the commodities actually bought by the wage earners. However, we cannot assume those purchases as known except in two extreme cases: when the net wage is zero, the gross wage is necessarily spent in buying the subsistence basket; and when the net wage is at its maximum, it is spent buying the entire surplus.

There is therefore a good reason in favour of the choice of the surplus (a composite commodity) as standard, which means making its value, i.e. the net national income, equal to unity (Sraffa, 1960, Section 12). This choice has an attractive consequence: with a suitable normalization of the social annual labour (total labour employed being taken as unity), the net wage can be seen to oscillate between 1 and 0, corresponding to a profit rate oscillating between 0 and its maximum value, determined according the production price.

However, there is a second and deeper reason why the emergence of a net wage makes the choice of the value standard important. The price enters the relation between the wage and the profit rate, and, as the price is affected by the choice of the standard, in a sense we can say that this choice affects the profit rate. The strategic variable of the economic system, showing its physical productivity or, more accurately, showing its capacity to produce a surplus net of wages, is affected by the choice of the standard: a most disturbing conclusion. And, from this point of view, the surplus is not a better standard than any other arbitrarily chosen commodity.

Sraffa set the following problem: is there a suitable standard so that the relation between the wage measured in terms of this standard and the profit rate becomes a simple function (linear, when the wage is paid post factum) not affected by prices?

The answer does not consist of an arbitrarily chosen commodity, i.e. wheat or iron: in other words, we cannot organize any wished ‘transparent’ accountancy on one or other of the two coordinate axes. We must utilize a composite standard (and therefore an oblique accounting line), but, unfortunately, the already suggested actual surplus will not normally work.

The solution consists in measuring the wage in terms of a basket of com modities, whose composition is a weighted average between the technical capitals used in the industries (where the weights are the components of their input vectors): the standard commodity (‘a medium between two extremes’: Sraffa, 1960, app. D, 2).

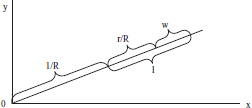

Our standard accountancy lies on an oblique line in the commodity space that coincides with the production price line (Figure 12.5 where: R is the maximum rate of profit; 1/R is the invested capital; r is the actual rate of profit; r/R is the profit; and w is the net wage). This elegant result was first noticed by Georg v. Charasoff (1910). But Charasoff was primarily interested in production prices and was not particularly concerned with the wage—profit relation. He did not pay attention to the properties of the newly discovered composite commodity as a value standard and developed instead an interesting but somewhat meta physical theory about an original substance, called Urkapital, which identifies every economic system.

Figure 12.5

At this stage of the analysis, the only remaining ‘arbitrary’ choice is the unit length along the accounting line: Sraffa considers the standard surplus corresponding to one unit of labour employed suitable for his purposes, and makes therefore equal to one the standard national income.

We are now able to consider a secondary, but no less controversial topic: the relation between the standard commodity and Ricardo’s corn model and his search for an invariable measure of value.

The Ricardian corn economy is popularly represented as a one-commodity world. At first sight, this is inconsistent with the original Ricardian proposition, that ‘it is the profits of the farmer that regulate the profits of all other trades’.

It could be easily answered, however, that the corn industry is a sort of core of a multi-commodity economy, and that is therefore analytically legitimate to consider it provisionally as a self-sufficient sub-economy. If we call x our corn, and if we adopt Sraffa’s conventions, we have the following equation:

Figure 12.6

where the wage, consisting of the corn necessary for subsistence, is included in the corn advanced for production (Figure 12.6). The production price in the equation proves the existence of another commodity in the economy, but does not play any role in the determination of the profit rate. Once r has been determined, we can easily calculate the price, assuming a uniform profit rate.

This is an interesting model that allows a sequential determination of the profit rate and of the price, but has nothing to do with Sraffa’s particular problem of the choice of the standard.

Let us consider the reference to the corn model that can be found in Production of commodities: the idea,

is that of singling out corn as the one product which is required both for its own production and for the production of every other commodity (…) Another way of saying this, in the terms adopted here, is that corn is the sole ‘basic product’ in the economy under consideration.

(Sraffa, 1960, app. D, 1)

(Remember also Section 6: ‘We shall assume throughout that any system contains at least one basic product’.)

Figure 12.7

Following this suggestion, we have the equation (see also Figure 12.7):

![]()

We can divide this by the price, which is no longer pleonastic:

![]()

where the wage does not necessarily consist of corn but is measured in terms of corn. The relationship between r and w is not independent of price, but depends on a price that can, so to speak, be sterilized by making it equal to unity.

This is the corn theory of profits found in Production of commodities. (But what of Ricardo? A suggestive statement by Sraffa can here be remembered: ‘it was only when the Standard system (…) had emerged in the course of the present investigation that the above interpretation of Ricardo’s theory suggested itself as a natural consequence’; 1960, app. D, 1.) It is definitely not a one-commodity model, because other non-basic commodities can be produced and priced. Neither is it an economy with a one-commodity industry in which the profit rate can be seen as a simple ratio between two homogeneous quantities. There is, in fact, no reason why wages should be spent on corn.

It is indeed a most interesting example, in which the ‘right’ choice of the accounting line is immediately evident to the observer. As we wish to obtain a simple and linear relation between wages and the profit rate, the correct line is the corn axis. The ensuing accounting system makes the economy wonderfully transparent.

In general, we cannot rely on a corn theory of profits: i.e. we cannot utilize a commodity axis as a suitable accounting line for our purposes. The standard system was devised precisely to identify in general the desired line in the positive quadrant.

Figure 12.8

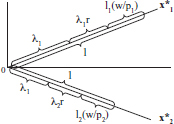

The way used here to present the problem of the standard of value may call to mind Goodwin’s ‘principal’ or ‘general’ coordinates (other names, such as ‘normalized’ coordinates are somewhat unfortunate, because the axes, as will be obvious, can no longer be orthogonal). However, the two approaches do not coincide.

Goodwin suggested transforming the present system of coordinates by which our commodity space is described into a new system of principal coordinates. In this new system, two different types of ‘corn’ (or of standard commodity) are measured on each axis, and we can use any coordinate axis as our accounting line. For every type of corn, we can show the following equation in the notation that is usual for linear models:

materials cost + profit on invested capital + labour cost =

![]()

where λi is the corresponding eigenvalue (Figure 12.8).

What we have here is a curious U-turn: the Ricardian corn example was used by Sraffa for singling out the general problem of finding a correct standard of value. The Sraffian solution — the standard commodity — is then used by Goodwin, in a most ingenious way, to reconstruct a sort of artificial corn economy that is valid generally.

The difference between the two approaches would be of a merely aesthetic character if the two problems could be proved to be equivalent, but they are not. It can be shown that the conditions for the existence of a meaningful system of principal coordinates are more restrictive than those usually required for the existence of one ‘standard’ accounting line in the positive quadrant.

Note

* Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche e Statistiche, Università di Trieste.

References

Charasoff, G. v. (1910) Das System des Marxismus, Berlin, H. Bondy.

Conigliani, C. (1900) Sul conguaglio dei saggi di profitto, in Archivio giuridico F. Serafini, Vol. 1.

Dmitriev, V.K. (1974 [1904]) Economic essays on value, competition and utility, London, Cambridge University Press.

Mühlpfordt, W. (1895) ‘Karl Marx und die Durchschnittsprofitrate’, in Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie, LXV.

Neumann, J. v. (1937) ‘Über ein ökonomischen Gleichungsystem und eine Verall — gemeinerung des Brouwerschen Fixpunktsatzes’, in Ergebnisse eines mathematischen Kolloquiums, VIII.

Sraffa,P. (1960) Production of commodities by means of commodities, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.