The aggregate neoclassical theory of distribution and the concept of a given value of capital

The lines of a more general critique

Paola Potestio

Introduction

Some years ago, in a book on The theory of production, Kurz and Salvadori (K—S hereafter) presented a reconstruction of the critique of neoclassical theory of distribution (Kurz and Salvadori, 1995). Using the main results of the debates on capital theory from the 1960s and 1970s, this reconstruction offered an opportunity to return to important aspects of those controversies that were left open in previous discussion. In particular, a crucial point of those controversies and K—S’s reconstruction deserves new consideration: the specific demonstration of the impossibility of extending the schema of the determination of distribution in the one—good economy (the so—called corn economy) to multi—good models. The current line of critique of the aggregate neoclassical theory of distribution, represented by this demonstration, is very weak. It can (and must) be corrected. Following previous contributions of mine on this theme,1 the aim of this paper is to further specify and develop the issue of reformulating in more effective terms the critique of the aggregate approach of neoclassical theory.

The critique of neoclassical theory of capital and distribution

The reference point of our discussion is the critique of the neoclassical theory of capital and distribution developed in Chapter 14 of K—S’s Theory of production. A long—period analysis (1995). This chapter deals with ‘The neoclassical theory of distribution and the problem of capital’.

In the first section of Chapter 14, the ‘core of traditional neoclassical theory’ is identified by K—S with the attempt to generalise the approach to the deter mination of wage and profit rates of the ‘corn’ economy to multi—good models. With continuously variable proportions of labour and corn in the production of corn, wage and profit rates can emerge from the equilibrium between given supplies of, respectively, labour and corn and demand curves for labour and corn that are given by the respective marginal product curves. How can this schema be extended to a framework with heterogeneous capital goods? The first point underlined by K—S is that, with heterogeneous capital goods, ‘Expressing the “quantity of capital” in given supply in value terms is necessitated’ (p. 430) by consistency with the long—term equilibrium that the theory aims to determine. A given capital endowment in kind would generally not be able to admit such an equilibrium. Thus

the ‘quantity of capital’ available for productive purposes had to be expressed as a value magnitude, allowing it to assume the physical ‘form’ suited to the other data of the theory.

(p. 431)

The analogy with the corn economy then requires that

With the ‘quantity of capital’ in given supply … a monotonically decreasing demand function for capital in terms of the rate of profit had to be established.

(p. 431)

The substitutability postulated by neoclassical theory between capital and labour in consumption (that is, the increase, as the rate of profit rises, in the relative prices of — and the consequent decrease in demand for — goods produced with a high proportion of capital to labour) and in production (that is, the switch, as the rate of profit rises, to more labour—intensive methods of production) would have assured the existence of such a decreasing demand function for capital. The way is therefore open to an explanation of distribution

in terms of the ‘scarcity’ of the respective ‘factors of production’: labour and capital, where the latter is conceived as a value magnitude that is considered independent of the rate of profit.

(p. 432)

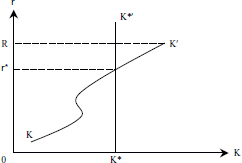

This, as the title of Section 1 anticipates, is considered ‘The core of traditional neoclassical theory’ and is synthesised in Figure 12.1, which therefore ‘appears to illustrate not only the hypothetical world with corn and capital alone, but also the “real world” with heterogeneous capital goods’ (p. 432). Of course, in this diagram, the curves KK′ and K*K*′ express, respectively, the demand function for capital (constructed on the hypothesis of full employment of the labour force) and the given supply of capital.

As is well known, this approach is undermined by a basic result, to which Sraffa’s Production of commodities by means of commodities (1960) made a prominent contribution: in multi—good models there is, in general, no possibility of obtaining a measure of capital that, being independent of the rate of profit, can contribute to the determination of the rate of profit itself. In Section 3 of Chapter 14 (devoted to ‘The critique of traditional neoclassical theory’) K—S observe, however, that, although the demonstration of this result is independent

Figure 12.1

of the occurrence of reswitching of techniques, the phenomenon of reswitching is also crucial in the critique of neoclassical theory, in that it ‘serves to counter the particular neoclassical claim of a decreasing demand function for capital’ (p. 447). They argue that, with a multiplicity of techniques, reswitching prevents the operation of the substitution principle postulated by neoclassical economists and thus the possibility of maintaining the properties of the neoclassical schema in the relations between wage and profit rates and the quantities of labour and capital.

K—S write:

The demonstration that a fall in w may lead to the adoption of the less ‘labor intensive’, that is, more ‘capital intensive’, of two techniques destroyed … the whole basis for the neoclassical view of substitution in production. More —over, since a fall in w may cheapen some of the commodities, the production of which at a higher level of w was characterized by a relatively low labor intensity, the substitution among consumption goods contemplated by the traditional theory of consumer demand may result in a higher, as well as in a lower, labor intensity. It follows that the principle of substitution in con sumption cannot offset the breakdown of the principle of substitution in production.

(pp. 447–8)

This critique is summarised by K—S in Figure 12.2. They comment:

if we conceived of the curve KK′ as the ‘demand curve’ for capital, which, together with the corresponding ‘supply curve’ K*K*′ , is taken to determine the equilibrium value of r, we would have to conclude that this equilibrium, although unique, is unstable. With free competition … a deviation of r from r* would lead to the absurd conclusion that one of the two income categories, wages and profits, would disappear. According to the critiques of traditional neoclassical theory, this result demonstrates all the more impressively the

Figure 12.2

failure of the supply and demand approach to the theory of normal distribution, prices and quantities.

(p. 448)

My aim is to show that this line of critique in one sense says both too little and too much, and that Figure 12.2, which summarises their position, is meaningless and therefore seriously misleading.

An assessment of the K—S critique

Premises

K—S’s critique raises two orders of problem. The first regards the interpretative aspects. The second concerns the analytical aspects or the analytical effectiveness of K—S’s critical approach.

This paper focuses essentially on the analytical aspects of the issues involved, not on the historical points of the development of neoclassical theory, nor on the specific characteristics of the positions of earlier neoclassical writers. Nevertheless, one might ask which neoclassical positions are actually depicted by Figure 12.1 and are thus the object of the critique of Figure 12.2, or even whether the schemas in Figures 12.1 and 12.2 correctly summarise these positions.

This question, i.e. the exact delimitation of the neoclassical field that is expressed and criticised by Figures 12.1 and 12.2, as well as the interpretative correctness of this schema, is not entirely clear in K—S’s discussion. They refer to two kinds of distinction within the neoclassical tradition. On the one hand, they distinguish between the macroeconomic version, founded on the aggregate production function, ‘with total labour employed together with the capital stock in existence’, and the microeconomic version,2 within which ‘production functions with capital as an input can be formulated for each single commodity’ (p. 432). On the other, on the basis of the consideration that ‘all versions of neoclassical theory start from the premise of a given endowment of the economy as a whole with a “quantity of capital”’ (p. 432), they distinguish between versions of neo —classical theory according to the way in which the given endowment of capital is intended. They identify three main references: the subsistence fund (Jevons, Böhm—Bawerk), the set of quantities of heterogeneous capital goods (Walras) and the value magnitude (Clark, Marshall, Wicksell). Which of these three versions, and their possible variants, may be encapsulated in Figures 12.1 and 12.2 is a subtle question that is not directly addressed or adequately clarified by K—S.3

Without entering into this question here, which largely pertains to the history of analysis, we must nevertheless recognise that the comparison between a given value of total capital and a demand for total capital to determine the rate of profit, which is the schema set out in Figures 12.1 and 12.2, directly reflects the approach of the neoclassical tradition that, in determining distribution, prices and quantities from the data — factors, technology and preferences — treats the given factors as (homogeneous) labour and capital in value terms. Thus, the version with capital as a value magnitude appears certainly to be a reference for the schema of Figures 12.1 and 12.2. The possibility, or the necessity, of reducing other approaches in the neoclassical field to such a schema falls outside the scope of this paper. Similarly, the exact extension of the ability of this schema to synthesise the position of individual scholars within the version that treats capital as a value magnitude and their respective variants is another question that falls outside our scope.

In conclusion — it is worth stressing — the focus of this paper emerges from the conviction that the serious conceptual problems underlying Figures 12.1 and 12.2 make it advisable to isolate the conceptual and analytical aspects from any issues concerning a reconstruction of the neoclassical tradition.

There is a second premise to our discussion. K—S’s critique is a reconstruction and a synthesis of positions within the neo—Ricardian field in the debate on capital theory. We will disregard the relation between this synthesis and the individual positions of neo—Ricardian authors that underlie that synthesis. Our reference is to the neo—Ricardian critique as it is formulated by K—S, a version that K—S seem to hold entirely in any case.

I will develop my discussion around four points: the quantity of capital in value terms in multi—good models, a brief note on the controversy between Böhm— Bawerk and Clark, substitutability in consumption, and the importance of reswitching and capital reversal.

The quantity of capital in value terms in multi—good models

As we have seen, K—S develop their critique essentially by asking whether the phenomena generated by the interdependence between prices and distribution preclude the possibility of verifying the properties that the curve KK′ exhibits in the corn economy and thus of considering the curves KK′—K*K*′ as determining the equilibrium rate of profit. Asking this question deserves much more attention. Actually, the scheme of curves KK′ and K*K*′ is highly questionable in multi—good models, quite apart from the occurrence or not of capital reversal and reswitching.

Let us start with the curve K*K*′, which expresses the assumption Ks = ![]() . The difficulties with this assumption are the following. Even accepting the automatic switch from assumptions on magnitudes in kind to assumptions on magnitudes in value,4 one can wonder about the meaning of ‘a given value of capital stock’. K—S raise no objection to the meaningfulness of this hypothesis and, hence, to the curve K*K*′. Their critique is founded solely on the possibility of perverse demand—side cases. Thus if, ad absurdum, perverse cases were not possible, we should conclude that K—S have no critique of this schema. Matters are rather different.

. The difficulties with this assumption are the following. Even accepting the automatic switch from assumptions on magnitudes in kind to assumptions on magnitudes in value,4 one can wonder about the meaning of ‘a given value of capital stock’. K—S raise no objection to the meaningfulness of this hypothesis and, hence, to the curve K*K*′. Their critique is founded solely on the possibility of perverse demand—side cases. Thus if, ad absurdum, perverse cases were not possible, we should conclude that K—S have no critique of this schema. Matters are rather different.

How can we conceive of ‘a given value of capital stock’? Does this mean that the value of capital is fixed in terms of a certain good or that the value is fixed whatever good is used to express it? The first case means, for example: Capital is ![]() dollars. If dollars are the numeraire, the given value of capital is

dollars. If dollars are the numeraire, the given value of capital is ![]() . Naturally, when we change the numeraire, the value of

. Naturally, when we change the numeraire, the value of ![]() changes.5 We can change the numeraire, but we cannot change the good in which capital is fixed. Thus, we cannot know the value of capital in any other good except

changes.5 We can change the numeraire, but we cannot change the good in which capital is fixed. Thus, we cannot know the value of capital in any other good except ![]() dollars. The second case means to conceive of the given capital in the long term as a sort of pure value entity: capital is not fixed in anything and is compatible with a possibly infinite series of quantities and baskets of goods.6 In this case, one might find it convenient to express the condition Ks =

dollars. The second case means to conceive of the given capital in the long term as a sort of pure value entity: capital is not fixed in anything and is compatible with a possibly infinite series of quantities and baskets of goods.6 In this case, one might find it convenient to express the condition Ks = ![]() in terms of a specific numeraire, but changing the numeraire does not change the assumed magnitude

in terms of a specific numeraire, but changing the numeraire does not change the assumed magnitude ![]() .

.

These two ways of conceiving the curve K*K*′, which we will indicate with K*K*′a and K*K*′b, respectively, must be assessed in a slightly different way and have different consequences for the critique of neoclassical theory. First, consider the reading K*K*′a. Following statements of neoclassical authors about the expression of the given value of capital in terms of a basket of consumption goods, K—S’s reference seems to be to this reading. Then, in their reply to Potestio (1999), they strongly reaffirm that taking into account the neoclassical consideration of capital as forgone consumption ‘the “quantity of capital” in given supply is to be expressed in terms of the consumption good (if there is only one) or, more generally, the consumption unit (that is, a bundle of consumption goods, if commodities are consumed in given proportions)’ (Kurz and Salvadori, 2001, p. 482). I fear that K—S fail to see the conceptual problem I raise. Unfortunately, this historical reading to which they refer cannot give substance to an inconsistent concept. Considering capital as forgone consumption can determine the choice of a numeraire, but cannot be a basis for fixing the good(s) in which capital must be expressed. In other words, this position can lead to choosing a unit of measure of capital, but cannot identify what capital is. The latter is a sort of metaphysical question, which, as such, is extraneous to any analytical argument. It is worth insisting in particular on the implications of these choices. The choice of a numeraire can obviously be changed. The identification of what capital is implies that we cannot change the good(s) in which capital is fixed and that we cannot know the value of capital in any other good except the one (those) in which it has been decided to identify capital. It is this arbitrary choice that underlies the K*K*′a reading. ‘Capital is 100 or 1000 consumption units’ has no serious economic meaning, just as any other definition that fixed the value of capital in any other good or basket of goods would have no substantive significance. This way of conceiving of a given value of capital stock must be considered untenable, and the hypothesis K*K*′a must be considered economically inconsistent.

Moreover, we also have to stress the consequences of reading K*K*′a as a consumption basket. As we cannot, in general, assume the structure of consumption before (simultaneously) determining distribution, prices and quantities, reading K*K*′ as a consumption basket requires (as K—S suggest) the adoption of a very special assumption, i.e. that consumption goods be consumed in given proportions. De facto, the hypothesis of given proportions amounts to making many consumption goods equivalent to only one consumption good.

To end our reading of K*K*′a, paradoxically it raises no difficulties only in a one—good context. In fact, the impossibility of a true generalisation to an economy with many consumption goods and the much more important impossibility, in any case, of an economically significant choice of the good(s) in which capital has to be fixed means that the only context in which any difficulty is surmounted is a one—good economy, a context in which no discussion of the neoclassical approach has ever emerged. Thus, if K*K*′a is the interpretation of the curve K*K*′, the critique of neoclassical long—term theory of distribution can immediately stop with the economic inconsistency of a value of capital fixed in something; that is, with the difficulties of curve K*K*′. Reswitching, capital reversal and the instability of the equilibrium of Figure 12.2 are unimportant for this critique, in the same sense in which the lack of a pen is unimportant for an illiterate person. It would be useful for such a person to have a clear idea of the relative importance of his lack of a pen and his illiteracy.

I do not feel I can judge K*K*′b as economically inconsistent. However, one can ask if the consistency of this reading goes together with a clear meaning of a concept of a pure value entity. Unfortunately, an affirmative reply seems impossible. In fact, the reading K*K*′b appears not inconsistent precisely because it has substantially no meaning.

In conclusion, the hypothesis of a long—term, given value of capital is either economically inconsistent or indefinite. In the first case, no other consideration is necessary to reject the schema of Figures 12.1 and 12.2. We will show in a moment that the second case also (apart from the vagueness of hypothesis K*K*′b ) does not leave any room for taking the schema of Figures 1 and 2 seriously.

Let us now consider the curve KK′. KK′ gives the value of total capital employed by firms at each level of r, under the assumption that employment is at its full level, ![]() . Obviously, this value depends on the choice of numeraire. Not having economic content, this choice cannot be but free. Now, dependence on the numeraire makes it impossible to interpret KK′ as a demand curve for capital. Changing the numeraire not only changes the value of capital employed at each rate of profit, but could also change the direction in which this value moves. As r rises, increasing values of capital with one numeraire could become decreasing values of capital with another numeraire. If this is the case, we can attribute no unique or important economic meaning to these movements in the value of capital as r changes. Hence, in general, the curve KK′ cannot be read as a demand curve for capital, whatever its behaviour may be.

. Obviously, this value depends on the choice of numeraire. Not having economic content, this choice cannot be but free. Now, dependence on the numeraire makes it impossible to interpret KK′ as a demand curve for capital. Changing the numeraire not only changes the value of capital employed at each rate of profit, but could also change the direction in which this value moves. As r rises, increasing values of capital with one numeraire could become decreasing values of capital with another numeraire. If this is the case, we can attribute no unique or important economic meaning to these movements in the value of capital as r changes. Hence, in general, the curve KK′ cannot be read as a demand curve for capital, whatever its behaviour may be.

The demand side of Figures 12.1 and 12.2 is as economically inconsistent as its supply side, a characteristic that obviously we can also extend to the equilibrium that emerges from these curves. Compare the demand side KK′ with the hypothesis K*K*′b. In this case, changing the numeraire does not affect curve K*K*′, but moves curve KK′. We, therefore, reach the totally meaningless result that if we interpret curves KK′—K*K*′ as demand for and supply of capital, the equilibrium profit rate depends on the numeraire. Changing the numeraire, the equilibrium profit rate, prices and quantities all have to change! Inconvenient characteristics of the equilibrium could possibly be transformed into virtuous characteristics simply by changing the numeraire. On the other hand, more meaningful results would not be obtained if we were expressing the supply side on the basis of hypothesis K*K*′a. In this case, changing the numeraire moves both KK′ and K*K*′. The value (or, possibly, values) of the profit rate at which Ks = Kd is (are) unaffected by the change of the numeraire, as is the nature (stable or unstable) of the equilibrium. Let us examine this point more closely. In general terms in equilibrium:

| (1) |

Changing the numeraire amounts to dividing both sides of (1′) by the price of the new numeraire (say, pj) in terms of the old numeraire (say, pi), i.e. it implies dividing both functions Ks and Kd by the function of r, (pj/pj)(r) ≡ g(r). Obviously, the change of the numeraire does not affect equilibrium (1′). To compare the slopes of the functions Ks and Kd in terms of the new numeraire j at the equilibrium point, differentiate Ks(r)/g(r) and Kd(r)/g(r) with respect to r:

Clearly, if Ksr > Kdr, Ksrg > Kdrg, and dKs(r)/dg(r) > dKd(r)/dg(r). The change in the numeraire does not change the relation between the slopes of Ks and Kd and thus the characteristics of the equilibrium.7

This demonstration, however, leaves a crucial question unsolved: in what sense within this framework can we reasonably speak of a stable or unstable equilibrium? To further underscore the importance of this question, let us refer to an extremely simplified model with two goods and given technique and quantities produced. We know that the relative priceP1/p2 (or p2/P1) is a monotonic function of r. Suppose that dp1/dr > 0 (p2= 1). In this case, it is easy to demonstrate that, if the given value of capital is expressed in terms of good 1, at the equilibrium value of r (if it exists),

![]()

whichever the chosen numeraire,8 i.e. the equilibrium is stable. Vice versa, if the given value of capital were expressed in terms of good 2, the equilibrium (if it exists) would be unstable. Opposite results hold if dp1 /dr 0.9 If capital were fixed in terms of some composite basket of goods 1 and 2, the equilibrium (if it exists) would be stable or unstable according to the weights x2 and x2. Note, incidentally, that, in this context, an unstable equilibrium is defined without any occurrence of reswitching and capital reversal. The point to stress, however, is that the necessarily arbitrary assumption of the good (or goods) in which the given value of capital is expressed is crucial in determining the stability or instability of the equilibrium. This arbitrariness, i.e. the economic inconsistency of hypothesis K*K*′a, can only lead to the complete meaninglessness of the nature of the resulting equilibrium.

Actually, the occurrence of reswitching and capital reversal phenomena risks losing its importance in a framework that is economically insubstantial. Thus, the critique of neoclassical theory of distribution can be immediately directed to the economic meaninglessness of the framework in Figure 12.1 itself (both its supply and demand sides) and its consequent inability to determine anything. In order to underscore the inability of Figure 12.1 to determine the rate of profit, there is no need to investigate which ‘perversities’ that framework can contain. We can stop before reaching this point, by simply observing that (1) the supply treatment is at best meaningless, and (2) the general interdependence between prices and distribution precludes any possibility of considering or assimilating curve KK′ with a demand curve for capital, whatever its behaviour may be.10

In conclusion, Figure 12.2 constitutes a fatal critique of neoclassical theory of distribution, not because there could be instability caused by reswitching of techniques, but because it expresses an exercise that is useless, inconclusive and without any economic meaning.

The critique of Hayek and Böhm—Bawerk

Despite our decision here to isolate the conceptual or analytical problems underlying Figures 12.1 and 12.2 from any historical reconstruction of the neoclassical tradition, we have to underline two strong critical positions against the concept of ‘pure capital’, i.e. the positions of Böhm—Bawerk and Hayek.

Without distinguishing the readings K*K*′ a and K*K*′ b, but referring to the tradition of the ‘subsistence fund’, Hayek defined the ‘given quantity of “capital disposal” or of “pure capital” in the abstract’ as ‘pure mysticism’ (Hayek, 1941, p. 93). A much more extensive discussion of the idea of the ‘true capital’ in Clark’s approach (Clark, 1899) is developed by Eugene Böhm—Bawerk. In two articles in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, Böhm—Bawerk harshly criticised the distinction between capital goods and pure capital as a basis for the theory of capital. Capital as ‘a permanent abiding fund of productive wealth’, ‘a quantum of matter of the kind defined as producers’ goods, measured in terms of value and having the characteristics of forever shifting its bodily identity’ (Clark, 1899, pp. 120–1), ‘an endless succession of shifting goods always worth a certain amount’ (Clark, 1899, p. 121) are the definitions that Böhm—Bawerk qualifies as totally unable to support capital theory. Böhm—Bawerk’s critique is radical: ‘a supply of true capital, which is not a supply of available capital goods, is pure necromancy’ (Böhm—Bawerk, 1907, p. 255). And further:

Would any one wish to base upon this state of facts, or rather upon this use of language, the scientific conclusion that the service is not identical with the totality of the pieces, but is an essential different entity? What manner of entity should this be? Surely, not bodily different. Is there a different spiritual entity, which is embodied as a sort of soul in the plates and knives? The notion is absurd. Or there is, perhaps, no entity at all, but only a mode of speech, a mere abstraction?

(Böhm—Bawerk, 1906, p. 8)

Böhm—Bawerk does not raise any particular objections to the abstraction of ‘capital’, but argues that this abstraction is removed from or harmful for economic theory:

If we ascribe to capital any real effect in production, we mean always the concrete capital goods. Professor Clark tries to intercalate a third notion between the abstract conception of capital and the concrete capital goods, and ascribes to this third thing a real existence as a material entity; which is simply an error. There is no such third thing.

(Böhm—Bawerk, 1906, p. 14)

Certainly the remarks by Hayek and Böhm—Bawerk represent an effective way of underscoring the difficulties of a concept of capital in the long term as a given value magnitude, a problem to which the controversies of the 1960s and 1970s unfortunately gave no attention. To comment on the Clark—Böhm—Bawerk debate briefly, while Böhm—Bawerk’s arguments appear very strong in rejecting the concept of pure capital, the implications of this concept, that is what a given value of capital analytically means, remain not completely clarified. Our readings K*K*′ a and K*K*′b have tried to underscore this aspect and clarify the insignificant consequences of the ‘given value of capital’ approach.

The substitutability in consumption

As we have seen, K—S’s critique of neoclassical theory attributes a strong role to substitutability in consumption. I would like to add some remarks on this issue.

To discuss this point, however, we have to start with substitutability in pro duction, which we will consider in isolation, so to speak, by stipulating that net products, y, are given. Now, it is unambigously possible to state when substitutability in production leads to normal or perverse cases. Let us refer to capital reversal, for which there is only the problem of correctly describing its occurrence. The switching points between two adjacent techniques on the frontier of factor prices permit an unambiguous comparison between the capital intensities of the two techniques, because production prices in both techniques are the same, whichever the numeraire one chooses.11 Let r = r* be a switch point between two techniques (A1, l1) and (A2, l2), where lj is the vector of unitary labour coefficients. At r = r*, w1 = w2 = w* and p1 = p2 = p*. From the equalities between the value of net product and the value added of the economy under the two techniques,12

subtracting the first from the second equation, we obtain the following relation:

![]()

where Lj is total employment. Suppose that, in moving from lower to higher levels than r*, there is a switch from the first to the second technique. The switch point (r*, w*) represents a perverse case if p*A2x2 − p*A1x1> 0. In this case, it also follows immediately that (p*A1x1)/L1 (p*A2x2)/L2. Changing the numeraire, the magnitude (p*A2x2 − p*A1x1) obviously changes, but its negativity or positivity is uniquely determined. Hence, with reference to switching points,13 we can unambigously state whether the optimising behaviour of firms as such — i.e. given y − leads to results in strict contrast with the neoclassical model.

Does substitutability in consumption make it possible to unambiguously identify perverse or normal cases?

To isolate substitutability in consumption, let us now suppose that there is only one technique (![]() ,

, ![]() ). Hence, there is no substitutability in production. In this context, only changes in final demands for goods, following changes in prices and distribution, lead to changes in demand for factors, capital and labour. Suppose that final demands y, and therefore activity levels x are continuous functions of prices p and distributive variables, w and r. In turn, prices p and real wages w are continuous functions of r. It is worth underscoring that, within this framework, we can unambiguously say what happens to L (=lx), the level of total employment, as real wages change. But we might not be able to say anything about the relation between the rate of profit and K (= pAx), the value of total capital employed, precisely because such a relation depends on the numeraire. Differentiating Kd = [p(r)Ax(p(r), w(r), r)] with respect to r yields

). Hence, there is no substitutability in production. In this context, only changes in final demands for goods, following changes in prices and distribution, lead to changes in demand for factors, capital and labour. Suppose that final demands y, and therefore activity levels x are continuous functions of prices p and distributive variables, w and r. In turn, prices p and real wages w are continuous functions of r. It is worth underscoring that, within this framework, we can unambiguously say what happens to L (=lx), the level of total employment, as real wages change. But we might not be able to say anything about the relation between the rate of profit and K (= pAx), the value of total capital employed, precisely because such a relation depends on the numeraire. Differentiating Kd = [p(r)Ax(p(r), w(r), r)] with respect to r yields

![]()

where the tth component of vector dx/dr is

![]()

Increasing values in r lead unambiguously to an increase in K (perverse case) only if, for any admissible numeraire, both terms

![]()

are positive, or the absolute value of the positive term between them is greater than the absolute value of the negative term. If neither case occurs, the value of total capital employed as r rises increases with some numeraires and decreases with others. This is not at all surprising. Moreover, it is useful to stress that, under a constant technique, we have no general points of reference that admit meaningful comparisons between the values of capital employed as r changes. Analogously, the circumstances under which an appropriate choice of the numeraire can change the direction of the change in the value of capital remain in general undefined in multi—good models.

Thus, to rely on substitution in consumption and to affirm that there can be circumstances in which ‘the principle of substitution in consumption cannot offset the breakdown of the principle of substitution in production’ is very difficult to specify more carefully. Actually, relying on substitution in consumption can introduce ambiguities. At switching points, we can unambigously compare the capital intensities of the two adjacent techniques: the numeraire has no influence, and final demands are equal. When we move from switching points, the changes in demands and quantities introduce a further element of indeterminacy, in addition to the changes in prices, for the behaviour of the value of capital. In summary, to investigate capital reversal, when demand and quantities change, is an exercise (a) that does not lead to general conclusions, and (b) possibly, may not lead to any specific and significant conclusions. Finally, I wish also to note that, even in those circumstances in which we can unambiguously state that the value of capital rises following an increase in r, it is very difficult to identify this case as a ‘perverse’ case. In fact, these circumstances include both the preference system of agents and the technology (![]() ,

, ![]() ). Thus, the nature of the rise of the value of capital does not seem sufficiently clear to permit us to define this case as a perverse case in the same sense in which such a definition is used in the analysis of substitution in production.

). Thus, the nature of the rise of the value of capital does not seem sufficiently clear to permit us to define this case as a perverse case in the same sense in which such a definition is used in the analysis of substitution in production.

The importance of reswitching and capital reversal

From the remarks in the section on ‘The quantity of capital in value terms in multi—good models’, it emerges that reswitching and capital reversal are unimportant for the critique of neoclassical distribution theory. K—S’s specific use of such phenomena to formulate this critique is at least unnecessary, and their claim that ‘to consider this phenomenon [reswitching] “unimportant” is difficult to sustain’ (p. 447) is unwarranted. The very fact of interdependence between prices and distribution within multi—good models prevents us from considering the relation between the rate of profit and the value of total capital employed as a demand curve for capital, precisely because the behaviour of this relation comes to depend on the chosen numeraire. To rely on reswitching ‘to counter the particular neoclassical claim of a decreasing demand function for capital’ (p. 447) is unnecessary and in a sense misleading, because it attributes to the relation between the value of capital employed and the rate of profit the role of a demand curve for capital, a role that this relation cannot meaningfully have. We can certainly compare switching points and thus techniques taking the curve KK′ as our reference, but this does not enable us, in general, to read this curve as a demand curve for capital.

If perverse cases, i.e. reswitching and capital reversal, are unnecessary for the critique of neoclassical theory of distribution, they still represent crucial points for denying significant general analogies between the simple production theory of the corn economy and the production theory of the fixed coefficients, multi—good economy. In particular, the importance of reswitching and capital reversal appears clearly and without ambiguities in a framework in which net products are maintained constant (or in simplified models, in which net product consists of only one good). The hypothesis of a given vector of net products permits us, so to speak, to isolate the optimising behaviour of firms. This is very useful, because reswitching and capital reversal have to do exclusively with this behaviour.

We cannot order techniques available to the economy in such a way that each switch leads to a technique that has never been used before, and the value of capital of the new technique adopted as r rises is always, at the prices of the switch point, lower than the value of capital of the technique that was dominant at lower levels of r. This is a strong result, and it is important to stress that it is additional to, and conceptually distinct from, the demonstration of the impossibility of constructing a meaningful demand curve for capital in multi—good models. The strength of this result lies in the fact that it eliminates any possibility, within the ground of the theory of production,14 of stating general analogies between one—good and multi—good models.

The schema of the corn economy for the determination of distribution simply vanishes in a multi—good world. The simple relations that the theory of production could state in the corn economy also collapse in such a world. The reasons for these failures are closely related, but it is useful to bear in mind that, at the same time, these reasons are conceptually distinct.

Conclusions

We have shown that the critique of the theory that tries to generalise the determination of distribution of the corn—economy model to multi—good models must be directly founded on the meaninglessness of both supply and demand curves for capital, whatever the behaviour of these curves may be. This implies the irrelevance of the phenomena of reswitching and capital reversal for this critique.

We have deliberately avoided analysing or taking into consideration the historical roots of the concept of a given value of the capital stock in the long term. We have chosen to concentrate only on its content, in order to underscore its economic inconsistency. This concept does not describe any reasonable supply of capital in the long term and represents a solution of a problem of aggregation of capital goods in the long term, which is simply unacceptable. The reading of the relation between the value of capital employed at each rate of profit and the rate of profit as a demand curve for capital appears to be equally meaningless, whatever behaviour this relation may have, depending on the chosen numeraire. The weakness of this treatment of supply of, and demand for, capital in aggregate terms gives rise to an equally weak concept of equilibrium, whose characteristics come to depend either on the chosen numeraire or the good or basket of goods in which it has been decided (without any logical basis) that the value of capital must be fixed. In conclusion, both the supply of, and demand for, capital are economically insignificant, and, consequently, they cannot say anything about either the long—term equilibrium or the adjustment processes towards such an equilibrium, quite independently from reswitching and capital reversal.

Notes

1 See Potestio (1996, 1999, 2001).

2 All the italics are in the original.

3 We should only note that this question has a trivial solution only for the Walrasian approach, which is clearly incompatible with Figures 12.1 and 12.2. Incidentally, even for this reason alone, doubts can be raised as to the identification of Figure 12.1 as the core of traditional neoclassical theory and the utilisation of Figure 12.2 as a general reference for criticising neoclassical tradition.

4 The general inconsistency with the long—term equilibrium, it is argued, forced neoclassical economists to assume the given quantity of capital in value terms. But the impossibility of assuming a given quantity of capital in kind per se only implies that the quantities must adjust for a long—term equilibrium. The step — capital cannot be given in kind, thus it must be given in value — is actually neither logically necessary nor automatic. This consideration, however, opens the way to a critical assessment of the positions of the individual neoclassical authors, a task that is outside the scope of this article.

5 Suppose mimetype="image" xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink" xlink:href="z_macro_i"/> is equal to $1,000. Quite obviously $1,000 in terms of corn are not equal to 1,000. Hence, note that, in this first case, the supply curve for capital is vertical only when we express relative prices in terms of the good in which capital was fixed.

6 Note that only in this case is it possible to translate the hypothesis, for example ‘given the value of capital in corn expressed in terms of money’ into the hypothesis ‘given the value of capital in money expressed in terms of corn’, precisely because capital is not fixed in anything, and thus changing the numeraire does not change the assumed value of capital.

7 This demonstration first appeared in Potestio (1996).

8 With p2 = 1, we have

as, by hypothesis, (dp2/dr) < 0 .

9 Moreover, observe the symmetry of results in this simplified model between the KK′—K*K*′a framework and the KK′—K*K*′b framework. Let dp1/dr > 0. With the supply of capital expressed in terms of good 1 (the KK′—K*K*′a framework) and with good 1 as the numeraire (the KK′—K*K*′b framework) the equilibrium, if it exists, is stable. If good 2 had been chosen in the two frameworks, the equilibrium would be unstable. Opposite results hold, if dp1/dr < 0.

10 I would like to note that this conclusion was implicit in Potestio (1993), in which the symmetrical demonstration of the meaninglessness of constructing a demand curve for labour ‘given K’, the value of the capital stock, was provided. Further, we should also recall here Burmeister’s (1980) insistence in the debates on capital theory on not reaching conclusions that depend on the numeraire.

11 See Pasinetti (1989), Chapter V. See also Pasinetti’s discussion in this chapter of traditional neoclassical theory. It is important to note that, in this discussion, Pasinetti explicitly assumes a stationary state only in illustrating capital reversal phenomena.

12 On this procedure for identifying phenomena of capital reversal, see D’Ippolito (1987a) and Potestio (1993).

13 If we compare the value of capital employed at any rates r1 and r2, at which techniques 1 and 2 are dominant, respectively, we do not necessarily obtain a unique result, that is a result that is invariant to the choice of the numeraire.

14 I wish, however, to note that there is one aspect of the importance of perverse cases that is still an open question. I am referring to the issue of the probability of such phenomena, an issue first raised in D’Ippolito (1987a, 1987b). Obviously, however, these aspects are not related to the matter at hand.

References

Böhm-Bawerk, E. (1906), ‘Capital and interest once more: I. Capital vs. capital goods’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, November, pp. 1–21.

Böhm-Bawerk, E. (1907), ‘Capital and interest once more: II. A relapse to the productivity theory’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, February, pp. 247–82.

Burmeister, E. (1980), Capital theory and dynamics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Clark, J.B. (1899), The distribution of wealth. A theory of wages, interest and profits. Reprint 1965, New York, Kelley.

D’Ippolito, G. (1987a), ‘Probabilità di perverso comportamento del capitale al variare del saggio dei profitti: il modello embrionale a due settori’, Note Economiche, 2, pp. 5–37.

D’Ippolito, G. (1987b), ‘Delimitazione dell’area dei casi di comportamento perverso del capitale in un punto di mutamento della tecnica’, in L.L. Pasinetti (ed.), Aspetti controversi della teoria del valore, Bologna, I1 Mulino, pp. 191–7.

Hayek, F.A. (1941), The pure theory of capital, London, Routhdge & Kegan Paul.

Kurz, H.D. and Salvadori, N. (1995), Theory of production. A long-period analysis, Cambrige University Press.

Kurz, H.D. and Salvadori, N. (2001), ‘The aggregate neoclassical theory of distribution and the concept of a given value of capital: a reply’, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, pp. 479–85.

Pasinetti, L. (1989), Lezioni di Teoria della Produzione, Il Mulino.

Potestio, P. (1996), On certain aspects of neo-Ricardian critique of neoclassical distribution theory, Discussion Papers, Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche, Università degli Studi ‘La Sapienza’, Roma.

Potestio, P. (1993), ‘Salario reale e domanda di lavoro: un confronto tra modelli con un numero diverso di merci’, Note Economiche, 1, pp. 37–61.

Potestio, P. (1999), ‘The aggregate neoclassical theory of distribution and the concept of a given value of capital: towards a more general critique’, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, pp. 381–94.

Potestio, P. (2001), ‘The aggregate neoclassical theory of distribution and the concept of a given value of capital: a counter-reply’, structural change and economic dynamics, pp. 487–90.

Sraffa, P. (1960), Production of commodities by means of commodities. Prelude to a critique of economic theory, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Steedman, I. and Metcalfe J.S. (1985), ‘Capital goods and the pure theory of trade’, in D. Greenaway (ed.), Current issues in international trade, London, Macmillan.