Sraffa and the interpretation of Ricardo

The Marxian dimension

Samuel Hollander*

Sraffa … bit out a piece of Ricardo’s shirt and ran it up on a flagstaff claiming that it was all that the man had on

(Sir John Hicks, letter dated 2 November 1978)

1 Introduction: Sraffa’s attributions to Ricardo

Piero Sraffa’s Production of commodities by means of commodities (PCMC) (1960) concerns the problem of a given physical surplus to be distributed to assure a uniform profit rate. Output levels (‘gross output quantities’) are included among the technological data determined outside the system along with the wage rate. (Alternatively, the profit rate may be taken as an independent variable and the wage as one of the unknowns (1960, p. 33).) Assume a physical surplus in the sense of an excess of one or more commodities over the amount(s) used up as input, then the (general) profit rate (r) will be determined ‘through the same mechanism and at the same time as the prices of commodities’ (p. 6), for to distribute the (physical) surplus so as to assure a uniform profit rate requires knowledge of prices in order to calculate the value of the means of production (which are heterogeneous products), while conversely to calculate the prices implies knowledge of r. But these propositions regarding price and profit-rate determination apply specifically to basic commodities, or commodities entering (directly or indirectly) as input into the production of all commodities including itself. The simultaneous emergence of profit rate and prices is not the case in the so-called standard system, where distribution has absolute priority. A brief summary of this position is in order.

Sraffa constructs a measure of value that has the property that it is itself invariable to a change in distribution; and though a change in distribution will alter its rate of exchange against other commodities produced under different technical conditions, the variation can be said not to ‘originate’ in the measure itself but in the commodities being measured. The ‘commodity’ in question is one produced with the ‘balancing input proportion’ recurring at all stages in the vertical production process (p. 16). Although no individual commodity is likely to have the requisite characteristics, a composite commodity can be constructed — it is a weighted average of ‘actual’ commodities, which includes all basics and only basics (pp. 23–5) — with the property that the commodity-mix of the aggregate (gross) product is identical with the commodity-mix of the aggregate means of production. Sraffa proves, first, that any ‘actual’ system can be reduced to a ‘standard system’ that describes the input—output relations relating to the sought-after composite commodity, and, second, that only one such miniature system will apply (p. 26 ff.). Finally, in the standard system, the ratio of net output to means of production (the standard ratio R) can be specified independently of prices, as effectively we have the same ‘physical’ commodity in the denominator and numerator of the expression — the proportionate mix of commodities being the same for both.

And now to the major uses of the device. First and foremost, changes in the division of the net product between wages and profits may affect relative prices in terms of the measure, but the ratio (R) of the net product to means of production in the standard system will be unaffected; indeed, the role of the standard system is to ‘give transparency to an [actual] system and render visible what was hidden’ (p. 23).1 Second, when the net product is divided between wages and profits — these shares as well as the total consisting of the standard commodity — then the rate of profit will equal the profit share times the standard ratio. Like the standard ratio itself, the rate of profit in the Standard system is effectively a ratio between quantities of commodities and is therefore unaffected by movements in relative prices (p. 22). These results may be expressed as

![]()

where r is the profit rate, w the share of wages in the net product, and R the standard ratio (or the maximum rate of profit). Variations of (proportionate) wages from 1 to 0 entail inverse variations in r in direct proportion, generating a straight-line inverse relation. Thus, in the standard system, with the wage paid in standard commodity units, the residual profit is also a quantity of that commodity, of the same mix precisely as the means of production. In brief, the profit rate is yielded as a physical ratio independent of relative prices — and a wage increase implies a directly proportional fall in the profit rate.

At first sight, Sraffa’s demonstration appears to be restricted entirely to the standard system as distinct from the ‘actual economic system of observation’ (p. 22). However, the straight-line relation in fact holds quite generally, ‘provided only that the wage is expressed in terms of the standard product’ (p. 23), for the equations of the actual system are identical to those in the standard system, except in their proportions. Given the wage in terms of the standard commodity, the profit rate is determined in both systems.

Sraffa represented PCMC as written from the ‘standpoint … of the old classical economists from Adam Smith to Ricardo [which] has been submerged and forgotten since the advent of the “marginal” method’ (1960, p. v). His ‘investigation’ would be ‘concerned exclusively with such properties of an economic system as do not depend on changes in the scale of production or in the proportions of “factors” allowing no place for marginal products or marginal costs’. To suppose his argument entails constant returns in all industries would be an error easily made by ‘anyone accustomed to think in terms of the equilibrium of demand and supply’. Such equilibrium evidently plays no role either in his own model or in his attributions to Ricardo.2

The Introduction to Ricardo’s Principles (1951) is further indicative of the relation Sraffa perceived between himself and Ricardo. Appendix D of PCMC alludes to that Introduction with reference to the corn-profit interpretation of Ricardo’s Essay on profits:

A method devised by Ricardo (if the interpretation given in our Introduction to his Principles is accepted) [in Ricardo 1951–73, I, pp. xxxi–xxxii] is that of singling out corn as the one product which is required both for its own production and for the production of every other commodity. As a result, the rate of profits of the grower of corn is determined independently of value, merely by comparing the physical quantity on the side of the means of production to that on the side of the product, both of which consist of the same commodity; and on this rests Ricardo’s conclusion that ‘it is the profits of the farmer that regulate the profits of all the other trades’. Another way of saying this, in the terms adopted here, is that corn is the sole ‘basic product’ in the economy under consideration.

(Sraffa 1960, p. 93)

Sraffa here represents the interpretation as a conjecture, arising only when, in the 1930s and early 1940s, ‘the standard system and the distinction between basics and non-basics had emerged’; it was then that the corn-ratio theory of profits ‘suggested itself as a natural consequence’. Yet more than a mere ‘rational reconstruction’ is actually at play, for Sraffa, in 1951, also maintained, positively, that Ricardo ‘must have formulated [the corn-profit model] either in his lost “papers on the profits of capital” of March 1814 or in conversation’ (emphasis added), and that he came close to an explicit statement in a letter of June 1814 (‘The rate of profits and of interest must depend on the proportion of production to the consumption necessary to such production’), and also in the table to the Essay on profits, which expresses both capital and ‘neat produce’ in corn and calculates the profit per cent ‘without need to mention price’ (Sraffa 1951–73, I, pp. xxxi–xxxii). More important still, we have moved far from a ‘rational reconstruction’ when Sraffa observes: ‘The advantage of Ricardo’s method of approach is that, at the cost of considerable simplification, it makes possible an understanding of how the rate of profit is determined without the need of a method for reducing to a common standard a heterogeneous collection of commodities’ (p. xxxii; emphasis added). As for the Principles, ‘the problem of value which interested Ricardo was how to find a measure of value which would be invariant to changes in the division of the product; for, if a rise or fall in wages by itself brought about a change in the magnitude of the social product, it would be hard to determine accurately the effect on profits’ (p. xxiii). Thus though the corn-ratio theory was no more than a passing stage, it constituted a type of analysis ‘render[ing] distribution independent of value’, and emerging again in the Principles where it was ‘labour, instead of corn, that appeared … both as input and output: as a result, the rate of profits was no longer determined by the ratio of the corn produced to the corn used up in production, but, instead, by the ratio of the total labour of the country to the labour required to produce the necessaries of labour’ (pp. xxxii–xxxiii).

To summarize: the features of PCMC attributed by Sraffa to Ricardo include a pricing analysis that denies a role for demand, with the outcome that equilibrium in the sense of profit-rate uniformity cannot be of the market-clearing variety; and construction of a measure of value with the property that it is itself invariable to changes in distribution, such changes treated as exogenous to the system.

I have questioned elsewhere Sraffa’s understanding of Ricardo (Hollander 1979, 1995). On my reading, Ricardo did not ignore the influence of demand on value and price, either of inputs or outputs, and either in the short or the long run, and treated supply and demand as functional relations, not fixed quantities. Output levels adjust to demand, and ‘natural’ prices satisfy the market-clearing condition (as was the case for Adam Smith); more generally, his economics allows for inter dependence between — and simultaneous determination of — prices, output levels, and the distributive variables.3 Assuming this to be the case, the question arises how Sraffa ‘may have gone astray’ (Bronfenbrenner 1989, pp. 40–1). Bronfenbrenner’s own ‘guess’ runs along these lines:

Sraffa was a Marxist, a refugee from Mussolini’s Fascist regime … Since Marx professed himself an admirer of Ricardo — as nearly a disciple as Marx could ever admit being of any predecessor — it may have seemed natural to attribute the same system first to Ricardo, and thence to classical economics in general — not, of course, to Smith, Malthus, Say, or the ‘hired prize-fighters’ of ‘vulgar economy’.

That Sraffa could only have come by his reading of Ricardo in post-Marx hindsight has been similarly argued by Pier Luigi Porta: ‘Sraffa [chose] to disguise Marx in a Ricardian garb’ (1986b, p. 484). For ‘no scholar of Ricardo would have discovered [the analogy between corn and the standard commodity suggested by Sraffa (1951–73, I, pp. x1viii–x1ix)] except through the Marxian reading of Ricardo’ (Porta 1986a, pp. 450–1). Porta points first to Sraffa’s admission that his corn-profit interpretation of the early Ricardo — entailing the determination of a rate of surplus independently of value — followed his own discovery of the standard system and the distinction between basics and non-basics in PCMC, implying that the interpretation constituted no more than a ‘logical by-product of the study of the standard system’, for there was ‘no evidence — as Sraffa acknowledged — that Ricardo ever explicitly recognized the importance of the rational foundation of his supposed “corn model”’ (pp. 444, 447, n. 22). Such a perspective Porta finds rather in Marx’s surplus doctrine, where surplus value emerges divorced from ‘the sphere of circulation’ or prices, with the market mechanism acting only at a subsequent stage to equalize profit rates (pp. 445–6). This is clear, runs Porta’s argument, from Marx’s use of a commodity (or commodities) of average capital composition in transforming the V-system (with its uniform s/v) to the P-system (with uniform profit rates), such that, in the average sphere(s), price corresponds to value, and profit to surplus, and the uniform profit rate corresponds to the rate prevailing in the average sphere(s) (pp. 447–8). The determination of the general profit rate in the sphere of average composition thus permits, at least in principle, an ‘escape [from] the logical necessity of determining the rate of profit and prices simultaneously’ (p. 448). Sraffa’s analysis of 1960 had ‘the merit of discovering a situation in which Marx’s approach works; certainly the standard system is one of those situations’ (p. 451).4

Not only does Porta reject the corn-profit reading of the early Ricardo (p. 447, n. 22). He also finds no analysis in the later Ricardo equivalent to Marx’s use of the mean commodity, so that Sraffa’s standard system is seen as wholly irrelevant to Ricardo (p. 444; also Porta 1979, pp. 91–7; 1982, pp. 734–7); Ricardo’s own ‘just mean’ had no more than negative significance as a sort of ‘counter example proving … the impossibility of finding an invariable measure of value’ (p. 444). In brief, only for Marx was the ‘true fundamental problem’ to obtain a measure of value invariant to changes in distribution (p. 444; also p. 445, n. 15). Ricardo’s ‘true problem’ entailed rather the link between diminishing returns and distributional change, and he proceeded with that analysis though he recognized that finding a measure was impossible (see also Porta 1992, p. xx).

* * *

This paper approaches the general position of Bronfenbrenner and Porta as a hypothesis: can the ‘Sraffian’ reading of Ricardo only be rationalized in ‘post-Marxian’ terms? I shall then go one step further and ask: how in actuality did Sraffa arrive at his reading? Section 2 demonstrates that to take the ‘Sraffian’ view requires that one constrains the reading of Ricardo to those parts of select chapters in the Principles — specifically Chapters 1 and 6 — involving highly simplified illustrative exercises. This constrained view neglects a broader body of evidence pointing to the market determination of wages and prices and their interdependence. Though a given wage permits (ceteris paribus) a ‘forecast’ of the average profit rate, independent of prices, and thus entails the priority of distribution, the wage is not in fact a datum, but is determined in the labour market and played upon both by the growth rate of capital (motivated by the return on capital) and the pattern of final demand, the latter itself partly governed by the (variable) income distribution. The breakdown between ‘surplus’ and ‘necessary’ labour time is, for Ricardo, a variable determined within the market economy. These objections to the Sraffa perspective are outlined in Section 3.

As an appropriately ‘truncated’ view of Ricardo does yield the Sraffian attributions, Professor Porta’s objections to the Sraffa reading prove too severe. Nonetheless, the hypothesis that the Sraffian perspective entails a reading through Marx’s spectacles cannot be dismissed, for it was certainly a central part of Marx’s programme to establish the priority of distribution.5 Anyone imbued with Marx’s vision and purpose would be predisposed towards the truncated perspective on Ricardo. Moreover, it seems to me perfectly reasonable for one to retain the ‘spirit’ of Marx, even though dispensing with the ‘letter’.6

What then do we know of Sraffa’s Marxian orientation? Sections 4 and 5 approach the issue in terms of the development of Sraffian historiography from the 1920s and draw heavily on the unpublished Cambridge Lectures on Advanced Theory, 1928–31. These materials support Porta’s position that Sraffa read Ricardo in a wholly Marxian fashion.7 I differ only in suggesting that there is an ‘objective’ dimension to this reading, taking the truncated view of Ricardo, where the profit-rate formula (should the denominator cover variable capital alone) emerges as identical with Marx’s rate of exploitation.

Throughout Sraffa’s accounts of the development of economics, we encounter his fervent hostility towards subjectivist economics, as manifested in functional relations entailing motivation to work and save, and in theories of value that formally allow for the demand side, characterized by Marshallian two-legged ‘symmetry’. Whether this hostility can be said to be ‘due to’ Marx is not wholly clear, but Sraffa’s praise along Marx’s lines for the Petty perspective on cost as ‘quantities of things used up in production’, and his ideologically centred reading of nineteenth-century developments, including the notion of the development of marginal-utility theory as a defensive reaction against Marx, are both suggestive.

2 The ‘truncated’ Ricardo and the Marx—Ricardo relation

The Sraffian perspective on Ricardo — at least Ricardo of the Principles — holds good as far as it goes. The problem is that it truncates Ricardo by concentrating on the profit-rate formula emerging in his Chapter 6 and applied in Chapter 1 to calculate equilibrium prices. Provided one takes so narrow a perspective, one may justify the Sraffa historiography. I proceed to clarify this assertion, attending first to a detail in the Ricardo formulation that justifies the emphasis on Ricardo’s concern to escape from the logical necessity of determining the profit rate and prices simultaneously.

As Sraffa explains, the chosen measure in the first two editions of Ricardo’s Principles is a commodity produced by given ‘unassisted labour’, regarded initially as an extreme type of process in terms of which, when the wage rises, all commodity prices decline; Ricardo, under pressure from Malthus, came in the third edition to represent this same commodity as a ‘just mean’ (allowing for com modities with a greater labour intensity) in terms of which some commodity prices rise with a rise in wages (1951–73, I, pp. x1iv–x1v). ‘If measured in such a standard’, Sraffa proceeds, ‘the average price of commodities, and their aggregate value, would remain unaffected by a rise or fall of wages.’ Ricardo himself emphasized the presumed circumstance that the majority of goods will not vary in price upon a change in the wage rate since most are produced under conditions of average composition.8 But he comes close to the Sraffa formulation in his Notes on Malthus:

To whatever corrections must be made for [the] irremediable imperfection in the most perfect measure of value that can be conceived, I have no objections to offer. It may affect some commodities one way, some the contrary way, the general average however will not be much affected.

(1951–73, II, p. 288)

And there is also a letter to J.R. McCulloch, dated 13 June 1820:

the medium between these two [extremes] is perhaps best adapted to the general mass of commodities; those commodities on one side of this medium, would rise in comparative value with it, with a rise in the price of labour, and a fall in the rate of profits; and those on the other side might fall from the same cause.

(1951–73, VIII, p. 193)

But it is McCulloch, in his exposition of Ricardo’s doctrine after his own conversion from Smithian price theory, who phrases the matter more precisly in the Sraffa fashion:

Though fluctuations in the rate of wages occasion some variation in the exchangeable value of particular commodities, they neither add nor take from the total value of the entire mass of commodities. If they increase the value of those produced by the least durable capitals, they equally diminish the value of those produced by the more durable capitals. Their aggregate value continues, therefore, always the same. And though it may not be strictly true, of a particular commodity, that its exchangeable value is directly as its real value, or as the quantity of labour required to produce it and bring it to market, it is most true to affirm this of the mass of commodities taken together.

(1825, pp. 312–13)

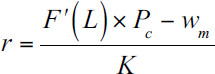

Ricardo’s presumption that most commodities, and pre-eminently corn, are produced under the same conditions as the mean measure coupled with the ‘Sraffa—McCulloch’ rationalization would help explain why he felt able to proceed in his main distribution chapters of the Principles in terms of a strict labour theory, thus avoiding the complications created by the possible effect of wage changes on relative values. In terms of such reasoning, he deduced his proposition that the profit rate is inversely related to labour’s proportionate share in the invariable value of the ‘marginal’ product — invariable precisely because of the constant labour embodied in that (variable) product. More specifically, he calculated absolute profits at the agricultural (and manufacturing) ‘margins’ as some constant reflecting the incremental labour application (his 10 men) less the labour embodied in the wages paid or F′(L) × Pc − wm, where F′(L) is the corn product at the margin, Pc the gold price of corn — ‘gold’ designed to serve as a measure of labour input such that Pc varies inversely to the marginal product of labour — and wm the gold wage, i.e. the labour embodied in the wage. A similar formula applies to manufacturing, where labour productivity, reflected in F′(L), is constant, such that,

in every case, agricultural, as well as manufacturing profits are lowered by a rise in the price of raw produce, if it be accompanied by a rise of [gold] wages. If the farmer gets no additional value for the corn which remains to him after paying rent, if the manufacturer gets no additional value for the goods which he manufactures, and if both are obliged to pay a greater value in wages, can any point be more clearly established that that profits must fall, with a rise of wages.

(1951–73, I, p. 115)

The rate of profit is then set by expressing profits relative to a capital stock (K) extending beyond wage goods. In Ricardo’s numerical example we have an initial situation with F′(L) at 180 quarters of corn, the price per quarter at £4, the wages of 10 men (earning a given fixed-proportions wage basket composed of corn and manufactures) at £240 and K at £3000, so that the profit rate

A decline in F′(L) to 170 qs and a corresponding increase in Pc to approximately £4.23 implies a larger wage deduction corresponding to the higher labour cost of producing the corn component in the wage basket, thus reducing the profit rate to

![]()

In brief therefore: ‘in all cases, the same sum of £720 must be divided between wages and profits’. The arbitrary choice of K = £3000 in fact adds little, since the major technical concern in the chapter on profits is to establish the numerator, especially the constant value of the (marginal) product in terms of Ricardian labour-measuring ‘gold’, such that the money wage reflects both labour embodied in the wage and proportionate wages. Nothing would have been lost as far as concerns the demonstration of a fall in the rate of profit with a rise in the money or proportionate wage, had the denominator been taken relative to a numerator reflecting solely the value of wage-goods capital, namely wm, especially as the substance of the argument in the chapter neglects fixed capital.

Marx fully appreciated that the more-inclusive capital tacked on at the end of the substantive argument added nothing essential and took Ricardo to task for effectively identifying the rate of profit with the rate of surplus-value (1968 [1862–3], p. 373; 1971 [1862–3], p. 236). As Marx read Ricardo, quite understandably,

Indeed, if we define Ricardo’s F′(L) × Pc as the value of the product due to a workday, taken as the minimum unit of labour (instead of the value of the product of 10 men), the modified formula for r expresses precisely the fraction of the workday devoted to producing goods for the capitalist-employer (Marx’s s) relative to the fraction devoted to producing wage goods (Marx’s v).

Now Ricardo’s position in his first chapter ‘On value’ takes for granted the result emerging later in his text, namely the inverse wage—profit relation: ‘There can be no rise in the value of labour without a fall of profits’ (1951–73, I, p. 35).9 But the later demonstration in his chapter ‘On profits’ is the same across all three editions of the Principles, though in the first and second he had assumed gold to be produced (like corn) by an ‘unassisted labour’ process, and in the third takes gold (again like corn) as a mean-proportions product. (As already mentioned, it is not the measure that changes in 1821 — only a recognition that some commodities entail more labour-intensive processes than gold and corn.) In either event, a labour theory is applied in the chapter ‘On profits», as uniform factor proportions are assumed in gold and corn (and manufactures), as evidenced by the fact that no price changes are generated by the wage change.10 The transition from an unassisted-labour measure to a mean-proportions measure in the 1821 chapter ‘On value’ allows prices to rise as well as fall upon a wage increase, but, as in 1817 and 1819, the inverse relation itself, whereby knowledge of the wage suffices to fix the profit rate independently of prices, is taken for granted as proven. Thus in 1821:

Suppose then, that owing to a rise of wages, profits fall from 10 to 9 per cent … all commodities which are produced by very valuable machinery, or in very valuable buildings, or which require a great length of time before they can be brought to market, would fall in relative value, while all those which were chiefly produced by labour, or which would be speedily brought to market would rise in relative value.

(p. 35)11

Now, as the third edition’s derivation of the inverse wage—profit relation in Chapter 6 is presumably based on the same measure as in that edition’s chapter ‘On value’ — it scarcely makes sense to switch measures between chapters — we have effectively the distributive rule based on the assumption that gold, corn, and manufactures are all produced by a mean process, which rule is then used to calculate the set of new equilibrium prices (satisfying the condition of uniform profit rates) emerging with an increase in wages, in the case of commodities produced with factor ratios deviating from the mean.

The profit rate is therefore derived by Ricardo in the mean industries — where value and price coincide (prices are unaffected by a change in the wage) — and then applied generally to all products. This is how Marx proceeded, with the difference that Ricardo obtained his profit rate in Chapter 6 on the basis of a strict labour theory of value, assuming uniform factor ratios, whereas Marx insisted on non-uniformity (his labour values in the transformation are non-equilibrium values).12

Ricardo was, then, as Sraffa maintained, preoccupied with obtaining a measure of value itself invariant to changes in distribution and in terms of which, given the wage, the profit rate can be calculated without the intrusion of prices. However, by working in terms of a strict labour theory in his distribution chapters, Ricardo cut corners; Marx’s procedures entail a more meaningful use of the measuring device, though Ricardo may be said to have invited such a use by his transition in the third edition between measures in the chapter ‘On profits’ to correspond to the switch in ‘On value’; and we have seen that McCulloch was inspired along these lines.

What though of Professor Porta’s insistence that Ricardo’s ‘true’ problem related to linking diminishing returns and distributional change, not to obtaining a measure of value invariant to changes in distribution? One must obviously allow for Ricardo’s conspicuous concern with the effect of diminishing returns on the wage and profit rates. But this concern in no way negates the ‘problem’ as set out by Sraffa. The exercise involving a constant value of a declining marginal product allowed Ricardo to demonstrate how, despite a falling real wage rate, the ‘gold’ wage — reflecting both labour embodied in the wage basket and proportionate wages — necessarily rises. If anything, the urgency of a solution to Ricardo’s problem as portrayed by Sraffa, is reinforced, not negated, by the diminishing-returns application.

3 Objections to Sraffa’s reading: Ricardo generalized13

The characteristic Sraffian priority of distribution emerges in Ricardo’s Principles, provided one concentrates solely on the formulae of Chapter 6 relating to surplus labour time. Given the wage (or assuming a given change in the wage), the profit rate (or its new level) can be forecast and then applied to ascertain the equilibrium structure of cost prices; distribution might then be said to have priority over pricing, in that relative prices will be such as to assure a uniformity of profit rates at a level dictated by the wage independently of pricing — precisely the impression Marx intended to convey by his transformation (and applied by him in his analysis of the inverse wage—profit relation) to the end of undermining productivity theories of distribution (1962 [1894], III, p. 805). Yet the notion of a ‘pre-existing’ surplus distributed across industries by a process of ‘circulation’ neglects the broader picture: the demonstrable fact that for Ricardo the wage is determined by labour-market pressures, including those exerted by the pattern of activity. Thus no ‘forecast’ can be made of the profit rate, as the wage is an endogenous variable partly dependent on the structure of final demand; distribution is not divorced from the pricing process, except in the context of the formal expository examples of Ricardo’s Chapters 6 and 1.

There is first Ricardo’s insistence on the validity of demand—supply analysis in general, an insistence that sets him apart from Sraffa. Here we do well to take note of Malthus’ distinction between cases of independent and interdependent demand—supply relations, with the negative link between quantity demanded and price applicable only where ‘demand is exterior to, or independent of, the production itself’; then only does contraction of supply raise price above costs, and conversely, in the opposite case (1986 [1815], pp. 7, 121–2; 1820, pp. 146–7; 1836, pp. 145–6). This situation, Malthus maintained, was ruled out in the case of corn:

In the production of the necessaries of life, on the contrary, the demand is dependent upon the product itself; and the effects are, in consequence, widely different. In this case, it is physically impossible that [1836: beyond a certain narrow limit] the number of demanders should increase, while the quantity of produce diminishes as the demanders [1820: can] only exist by means of this produce.

Ricardo objected, drawing attention to the subjective dimension: ‘the question is not about the number of demanders but of the sacrifices they are willing to make to obtain the commodity demanded. On that must its value depend’ (1951–73, II, p. 114). And in the Principles, he insisted that the demand—supply mechanism applied equally to all products including corn,

for you would as surely raise the rent of land yielding scarce wines, as the rent of corn land, by increasing the abundance of its produce, if, at the same time, the demand for this peculiar commodity increased; and without a similar increase of demand, an abundant supply of corn would lower instead of raise the rent of corn land.

(1951–73, I, p. 405)

The fallacious contrast could in part be explained by the presumption that increased food supply preceded population growth and demand: ‘

Mr. Malthus appears to me to be too much inclined to think that population is only increased by the previous provision of food, — ‘that it is food that creates its own demand’ — that it is by first providing food, that encouragement is given to marriage, instead of considering that the general progress of population is affected by the increase of capital, the consequent demand for labour, and the rise of wages; and that the production of food is but the effect of that demand.

(p. 406)

As for cost prices, these depended on output levels and therefore upon demand. In the first place, the magnitude of labour costs in agriculture is in part determined by the degree of land scarcity. For example, should pressure on land be relaxed in consequence of a fall in the demand for corn, or an effective increase in land supply, marginal (labour) costs and long-run price would be reduced:

Any circumstances … which should make it unnecessary to employ the same amount of capital on the land, and which should therefore make the portion last employed more productive, would lower rent … Every reduction of capital is … necessarily followed by a less effective demand for corn, by a fall of price, and by diminished cultivation.

(p. 78)

Consider next a net increase in the demand for domestic corn due to the granting of a corn-export subsidy. If agriculture is a constant-cost industry (as Ricardo provisionally assumes), the adjustment proceeds until the corn price, initially raised above costs, falls to its original level (pp. 301–2). But, in the more usual case, the equilibrium outcome reflects a higher marginal labour cost and corn price:

I have already attempted to show, that the market price of corn would, under an increased demand from the effects of a bounty, exceed its natural price, till the requisite additional supply was obtained, and that then it would again fall to its natural price. But the natural price of corn is not so fixed as the natural price of manufactured commodities; because, with any great additional demand for corn, land of a worse quality must be taken into cultivation, on which more labour will be required to produce a given quantity, and the natural price of corn will be raised.

(p. 312; emphasis added)

Here Pc/Pm rises with a switch in the policy-induced pattern of demand favouring agriculture.14

An equally clear indication of the role Ricardo accorded demand in determining the margin, and the relevant marginal labour costs, is provided by the analysis of a contemporary case where certain firms in an industry had their labour costs subsidized, thus generating a (discrete) increasing-cost supply schedule. The appropriate margin and corresponding marginal labour cost are explicitly assumed to be governed by ‘the quantity of produce required’, i.e. by demand considerations. Should the level of demand be sufficiently low for the output of the subsidized firms alone to be ‘equal to all the wants of the community’, the unsubsidized firms would be excluded, and the equilibrium will be determined by the low-cost conditions; at a higher demand, the higher marginal cost becomes pertinent (p. 73).

The role of demand in determining the location of the margin and thus marginal cost emerges very clearly in the analysis of population expansion, particularly in objections against Malthus’s linkage of population growth to preceding accumulations of food. Only if improved living conditions with higher demand for labour should generate higher marriage and birth rates will there occur an increased demand for food — in place of worker’s demand for luxuries — and in that case the agricultural margin is extended in response:

When a high price of corn is the effect of an increasing demand, it is always preceded by an increase of wages, for demand cannot increase, without an increase of means in the people to pay for that which they desire. An accumulation of capital naturally produces an increased competition among the employers of labour, and a consequent rise in its price. The in creased wages are not [‘not always’ in the third edition] immediately expended on food, but are first made to contribute to the other enjoyments of the labourer. His improved condition however induces, and enables him to marry, and then the demand for food for the support of his family naturally supersedes that of those other enjoyments on which his wages were temporarily expended. Corn rises then because the demand for it increases, because there are those in the society who have improved means of paying for it; and the profits of the farmer will be raised above the general level of profits, till the requisite quantity of capital has been employed on its production.

(pp. 162–3; emphasis added)

Long-run cost price may rise or stay unchanged, depending on the constancy or otherwise of (marginal) costs:

whether, after this has taken place, corn shall again fall to its former price, or shall continue permanently higher, will depend on the quality of the land from which the increased quantity of corn has been supplied. If it be obtained from land of the same fertility, as that which was last in cultivation, and with no greater cost of labour, the price will fall to its former state; if from poorer land, it will continue permanently higher.15

Changes in demand patterns thus directly affect relative long-run cost prices by playing upon the margin of cultivation. But there may also be an effect on relative cost prices generated by an alteration in distribution, turning on the allocative rule that ‘through the inequality of profits … capital is moved from one employment to another’ (p. 119). In the event that the wage increase impinges equally on all commodities, prices are unaffected, so that profits are uniformly depressed. But in the general case, a wage increase does disturb the structure of profit rates, thereby setting in motion appropriate supply adjustments that lead to the establishment of a new long-run cost-price structure, assuring again uniform profit rates in all industries, with markets cleared at a lower general level. This mechanism — which is the only one fully consistent with Ricardo’s own analysis of economic adjustment — is in fact explicitly elaborated in his exposition of Ricardian theory by McCulloch, who spells out (1) the expansion of relatively capital-intensive, and contraction of relatively labour-intensive, industries — and the corresponding price adjustments — engendered by the initial wage-rate change; and (2) the constancy of the supply and therefore of the prices of commodities produced with the ‘medium’ coefficients:

It is plain, however, that this discrepancy in the rate of profit [created by the initial wage increase] must be of very temporary duration. For the undertakers of those businesses, in which either the whole or the greater portion of the capital is laid out in paying the wages of labour, observing that their neighbours, who have laid out the greater portion of their capital on machinery, are less affected by the rise of wages, will immediately begin to withdraw from their own businesses, and to engage in those that are more lucrative. The class of commodities produced by the most durable capitals, Nos. 7, 8, 9, 10, &c. will, therefore, become redundant, as compared with those produced by the least durable capitals, Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, &c.; and this increase on the one hand, and diminution on the other, will have the effect to sink the value of the commodities produced by the most durable capitals as compared with those produced by the least durable; or, which is the same thing, to raise the value of the latter compared with the former, till they all yield the same rate of profit.

The class of commodities produced by capital of the medium degree of durability, or by No. 6, would not be affected by the rise; for, whatever they lost in exchangeable value, as compared with the commodities produced by the less durable capitals, they would gain as compared with those produced by the more durable capitals.

(1825, pp. 303–4)

Inter-industry substitution thus provides the key to the Ricardian analysis of the allocative effects of a wage change; and in the general case of non-uniform factor ratios such changes in distribution affect relative cost prices by generating appropriate output variations. There is not that separation of value and distribution characteristic of the Sraffian system.

The interdependence of distribution and pricing extends further. Ricardo maintained the market determination of the wage, taking account of a possible effect on the wage exerted by the pattern of final demand by way of relative factor scarcity. Consider his analysis of the transition from war to peace:

At the termination of the war, when part of my revenue reverts to me, and is employed as before in the purchase of wine, furniture, and other luxuries, the population which it before supported, and which the war called into existence, will become redundant, and by its effect on the rest of the population, and its competition with it for employment, will sink the value of wages, and very materially deteriorate the condition of the labouring classes.

(1951–73, I, pp. 393–4)

From this it followed that ‘the labouring class have no small interest in the manner in which the net income of the country is expended’ (p. 392); ‘they must naturally desire that as much of the revenue as possible should be diverted from expenditure on luxuries, to be expended in the support of menial servants’ (p. 393). A second illustration entails alternative capital compositions induced by alternative taste patterns:

A society does one or the other [invest in labour — or machine-intensive processes] in proportion to the demand for either the objects of men’s work; or for objects which are almost exclusively produced by machinery; — in general the capital accumulated will consist of a mixture of both, of fixed and of circulating capital … [To] the capitalist it can be of no importance whether his capital consists of fixed or of circulating capital, but it is of the greatest importance to those who live by the wages of labour … If capital is realized in machinery, there will be little demand for an increased quantity of labour, — if it create an additional demand for labour it will necessarily be realized in those things which are consumed by the labourer.

(1951–73, II, pp. 234–6)

It should be added that Ricardo also recognized the reverse effect of variations in distribution on the pattern of demand, thereby endogenizing the latter: ‘if in the division of the gross produce, the labourers commanded a great proportion, the demand would be for one set of commodities — if the masters had more than a usual share, the demand would be for another set’ (1951–73, VIII, pp. 272–3).

The market determination of the wage is elaborated in the context of secular tendencies. There is first the initially upward course of the real wage in an economy not yet subject to land scarcity:

It has been calculated, that under favourable circumstances population may be doubled in twenty-five years; but under the same favourable circumstances, the whole capital of a country might possibly be doubled in a shorter period. In that case, wages during the whole period would have a tendency to rise, because the demand for labour would increase still faster than the supply.

(1951–73, I, p. 98)

This is followed by a subsequently declining course of the real wage under the market pressures engendered by increasing land scarcity:

In the natural advance of society, the wages of labour will have a tendency to fall, as far as they are regulated by supply and demand; for the supply of labourers will continue to increase at the same rate, whilst the demand for them will increase at a slower rate. If, for instance, wages were regulated by a yearly increase of capital, at the rate of 2 per cent, they would fall when it accumulated only at the rate of 11/2 per cent. They would fall still lower when it increased only at the rate of 1 or 1/2 per cent., and would continue to do so until the capital became stationary, when wages also would become station ary, and be only sufficient to keep up the numbers of the actual population.

(p. 101)

Now, as capital growth rate is partly motivated by the return on capital — ‘The motive for accumulation will diminish with every diminution of profits’ (p. 111) — the entire concept of ‘surplus’ is undermined.

The market (‘demand—supply’) determination of the real wage, the application of demand—supply analysis to pricing (including corn pricing) and to the inverse wage—profit relation; the dependence of long-run cost prices both upon demand — in the presence of increasing-cost industries — and upon distribution; and the endogenization of the pattern of demand combine to create an impenetrable barrier between the Sraffian and Ricardian orientations.

4 The origins of Sraffa’s reading of Ricardo16

Our conclusion thus far leads on to the obvious question: why did Sraffa take the ‘narrow’ view of Ricardo? The general Bronfenbrenner—Porta hypothesis (above, Section 1), that Sraffa ‘mistook’ Ricardo for Marx, cannot be dismissed out of hand, as anyone starting out from Marx would be encouraged to read Ricardo in the same light. But this is inconclusive, as many non-Marxists have read Ricardo thus, at least insofar as concerns the alleged denial of demand—supply analysis and the subsistence-wage attribution. To make any progress with our investigation, we must consider Sraffian historiography itself.

Classical value theory

In summer 1921, Sraffa as a ‘general research student’ attended Edwin Cannan’s course at the LSE on the theory of value and distribution (Potier 1991, 8). We can be sure then of an early familiarity with Ricardo.17 And we have information regarding his perspective on the English classics soon afterwards.

In an obituary notice of 1924, Sraffa described Maffeo Pantaleoni’s Principii di economia pura (1889) as ‘the first organic treatise in which — in accordance with the teaching of Marshall — the doctrines of the classical writers were harmonised with the new theories of Gossen and Jevons’, and also as ‘the most efficacious disseminator of the theory of utility in Italy as well as in other Latin countries’ (1924, pp. 650–1). This would suggest a cost-oriented perspective, of some sort, on classical value theory. The 1925 essay ‘Sulle relazioni fra costo e quantità prodotta’ — which rejected the Marshallian ‘teoria simmetrica’ on the grounds of two sorts of interdependence in cases where diminishing returns apply, namely that between the supply (cost) curves of the various industries and that between the supply and demand curves of each individual industry (Sraffa 1986 [1925], pp. 59–60)18 — refers to the constant-cost case as ‘normal’, in keeping with the opinion of Ricardo: ‘si debba, caso mai, riguardare come normale il caso dei costi costanti, piuttosto che quelli dei costi crescenti o decrescenti. Tale doveva essere l’opinione di Ricardo, poiché egli afferma che le merci che possono venir prodotte a costi costanti costituiscono “di gran lunga la maggior parte delle merci che vengono giornalmente scambiate sul mercato”’ (p. 54, citing Ricardo 1951–73, I, p. 12). Sraffa thus regarded Ricardian diminishing returns as at most a special case. And this is confirmed in the 1926 paper on ‘Laws of return under competitive conditions’. Here, Sraffa again insisted that interdependence between supply and demand conditions flowing from variation of return precluded ‘the study of the equilibrium value of single commodities produced under competitive conditions’; for the assumption of independence ‘becomes illegitimate, when a variation in the quantity produced by the industry under consideration sets up a force which acts directly, not merely upon its own costs, but also upon the costs of other industries; in such a case the conditions of the “particular equilibrium” which it was intended to isolate are upset, and it is no longer possible, without contradiction, to neglect collateral effects’ (1926, pp. 538–9). And, as in 1925, the relevance of diminishing returns for the classical analysis of value is said to be minimal:

The law of diminishing returns has long been associated mainly with the problem of rent, and from this point of view the law as formulated by the classical economists with reference to land was entirely adequate. It had always been perfectly obvious that its operation affected, not merely rent, but also the cost of the produce; but this was not emphasised as a cause of variation in the relative price of the individual commodities produced, because the operation of diminishing returns increased in a like measure the cost of all. This remained true even when the English classical economists applied the law to the production of corn, for, as Marshall has shown, ‘the term “corn” was used by them as short for agricultural produce in general’.

(Marshall 1920, VI. I. p. 2, note)

The position occupied in classical economics by the law of increasing returns was much less prominent, as it was regarded merely as an important aspect of the division of labour, and thus rather as a result of general economic progress than of an increase in the scale of production.

The result was that, in the original laws of returns, the general idea of a functional connection between cost and quantity produced was not given a conspicuous place; it appears, in fact, to have been present in the minds of the classical economists much less prominently than was the connection between demand and demand price.

The development that has emphasized the former aspect of the laws of returns is comparatively recent. At the same time, it has removed both laws from the position that, according to the traditional partition of political economy, they used to occupy, one under the heading of ‘distribution’ and the other under ‘production’, and has transferred them to the chapter of ‘exchange value’; there, merging them in the single ‘law of non-proportional returns’, it has derived from them a law of supply in a market such as can be co-ordinated with the corresponding law of demand; and on the symmetry of these two opposite forces it has based the modern theory of value (1926, pp. 536–7; emphasis added).

To summarize: at this early stage, Sraffa perceived the ‘classical economists’ as working either with constant costs or with increasing costs, which, because they apply across-the-board are irrelevant to relative price determination. And though he did recognize their connecting ‘demand and demand price’, he did not attribute to them Marshall’s ‘fundamental symmetry’ of demand and supply. This fact is also implied by a further observation that such symmetry rendered value theory irrelevant in the study of ‘social change’, an issue that had preoccupied Ricardo and Marx:

A striking feature of the present position of economic science is the almost unanimous agreement at which economists have arrived regarding the theory of competitive value, which is inspired by the fundamental symmetry existing between the forces of demand and those of supply, and is based upon the assumption that the essential causes determining the price of particular commodities may be simplified and grouped together so as to be represented by a pair of intersecting curves of collective demand and supply. This state of things is in such marked contrast with the controversies on the theory of value by which political economy was characterised during the past century, that it might almost be thought that from these clashes of thought the spark of an ultimate truth had at length been struck. Sceptics might perhaps think the agreement in question is due, not so much to everyone being convinced, as to the indifference which is justified by the fact that this theory, more than any other part of economic theory, has lost much of its direct bearing upon practical politics, and particularly in regard to doctrines of social changes, which had formerly been conferred upon it by Ricardo and afterwards by Marx, and in opposition to them by the bourgeois economists.

(p. 535; emphasis added)19

Sraffa’s unpublished Lectures on the Advanced Theory of Value given in 1928–31 to Cambridge University students suggests that he had come to regret the formulation of 1926 which implied that the premises of orthodox theory did hold good in the case of constant returns (cf. Sraffa 1960, p. vi). For we now find an indication of the ‘standpoint’ of 1960 that allowed no place for marginal products or marginal costs (above, Section 1), expressed in the assertion that the classics did not operate with a functional relation between costs and quantity produced; even the notion of ‘classical’ constant costs was anachronistic:

The interdependence of cost and quantity produced is quite a modern idea. All the classical economists ignore it altogether so much so that it cannot even be said that they assume constant costs to operate throughout, as their argument implies, since they don’t take the question into consideration at all; and their discussions of what are the causes of value refer only to whether it is only the quantity of labour, or also profits and also rent: but they are all agreed in looking for the causes only on the side of supply.

It was only with the introduction of the concept of marginal utility that a possible quantitative connection between value and utility was perceived; and it was only after this, and in consequence of it that the variations of cost as a function of quantity produced were connected with the determination of value.

The dependence of marginal utility upon the quantity of the commodity consumed is immediate and obvious; in fact marg. ut. [sic], being the rate of increase of total utility cannot be conceived apart from variations in quantity consumed. But cost of production per unit is an independent notion, that was quite clear long before that of marginal costs.

(PSP, D2/4, pp. 66–7)

As for the so-called ‘laws’ of increasing and diminishing returns, though well known to the classics, they were not applied to the theory of relative value at all, but to aspects of ‘production’ theory:

Increasing returns indeed played a very little part in classical economics, the only aspect taken into consideration being that of division of labour as a means of increasing productiveness: but division of labour was regarded much more as a result of the general progress of society than of the growth of a particular industry.

(p. 68)

A comment on the classical treatment of diminishing returns to the effect that all products are affected equally so that relative prices remain unchanged, confirms the published version of 1926, with an added identification of Ricardo with Petty on usage of the term corn:

The increase in cost consequent to an increased application of capital and labour to land, reduced the means of subsistence available per head of a larger population, and increased the share of the landlord in the produce. But it could not change the values of particular commodities because diminishing returns from land affected to the same extent different commodities, because they all, directly or indirectly, were products of agriculture, and therefore their relative positions remained unchanged. It is true that Ricardo usually speaks only of the production of corn in connection with diminishing returns: but no doubt he uses the term ‘corn’ for agricultural produce in general, as Sir W. Petty, in an often quoted passage, speaks of the ‘Husbandry of Corn, which we will suppose to contain all the necessaries of life, as in the Lord’s Prayer we suppose the word Bread does’

(Marshall, p. 509n) (Sraffa, pp. 68–9)20

Sraffa then summarized by insisting that a fortiori the two tendencies of increasing and diminishing returns were never put on the same plane by the classics: ‘But even less than they saw any connection between the cost of a particular product and the quantity produced, did they see that there was any similarity between the two opposite tendencies’. Responsibility for such parallelism, and more generally for the ‘coordination of supply with demand conditions’, is laid at Marshall’s door: ‘All this: coordination between the two; connection between quantity and cost; coordination with demand is [a] very recent development, chiefly [the] work of Marshall, and [a] consequence of [the] theory of marg. ut. [sic] and attempt at compromise’ (p. 69). Marshall’s responsibility for ‘unifying’ the Ricardian cost approach with the Jevonian utility approach had been spelled out earlier in the Lectures thus:

The point I wish to make is the independence in the development of the two opposite conceptions, of cost and utility. In M’s theory they appear as closely connected, in fact they are for him two quantities of the same nature one positive and the other negative; they can be added or subtracted and balanced against one another. But this unification, and therefore the statement of the symmetry between cost and utility, and through them of supply and demand, has been to a large extent the result of Marshall’s work — not of the historical development of the theory of value. Their origin has to be traced to entirely distinct sources, and their development has been quite independent of one another. Then Marshall brought them together and has made an attempt to conciliate the two opposite views, which I shall refer to as of Ricardo and of Jevons, each of whom thought that it was possible to group all causes of values under one single notion, at the exclusion of the other. What is important to realize, however, is that the notion of cost of production, as understood by the classical economists, would not have allowed such a unification; to make this possible it had itself to pass through a series of small changes which gradually brought it to its present position. It is only when cost is conceived as a quantity of disutility, that is to say, of negative utility, that is can be brought together with marginal utility in a single theory of value.

(pp. 17–18)21

On classical ‘surplus’ theory

We take up next various propositions in Sraffa’s Cambridge Lectures relating to the classical notions of ‘surplus’ and ‘costs’. These clearly presage the Introduction to the Works and correspondence of David Ricardo (1951), particularly the corn-profit interpretation there given of the Essay on profits and the extension to labour attributed to the Principles.

In this context, Sraffa contrasts Marshall’s ‘real cost’, in the sense of ‘efforts and sacrifices’ respecting waiting and labour, with what in the theories of Petty and the Physiocrats ‘plays the role of cost’, namely

a stock of material, that is required for production of a commodity; the material being of course mainly food for the workers. But Petty wants to make it quite clear that his notion of cost has nothing to do with the pleasant or unpleasant feelings of men, and he defines ‘the common measure of value’ as ‘the day’s food of an adult Man, at a Medium, and not the day’s labour’.

This cost is therefore something concrete, tangible and visible, that can be measured in tons or gallons. It stands therefore at the opposite extreme of Marshall’s cost, which is absolutely private to each individual, and can only be measured (if at all) by means of the monetary inducement required to call forth the exertion.

(PSP, D2/4, p. 21)22

Thus for Marshall wages and profits,

are the inducement required to call forth certain sacrifices … and … also the reward of those sacrifices. Their importance to production is equally subordinate: what is really necessary for producing is only the efforts, not their rewards. It is not necessary for the actual goods which compose real wages and profits to be in existence at the beginning of the process of production — the hope, or the promise, of these goods is equally effective as an inducement. They operate on production only by being expected; but they come into existence only when production is finished, as shares in the product.

(pp. 23–4)

But ‘Petty and all the classics … don’t regard at all wages as an inducement; they regard them as necessary means of enabling the worker to perform his work’ (p. 24). Accordingly:

Wages are the stock of goods that exists before production and which is destroyed during the productive process: they come thus to be identified with capital or at least an important part of capital. Profits (and rent of course) are a part of the product, and precisely the excess of the product over the initial stock. All the product belongs to the capitalist, who has advanced the wages: out of it he draws his profits and uses the rest to replace the capital consumed, thus replenishing the wages fund to be used in the following process of production. There never is at any moment of time, a division of the product between capitalist and worker; their incomes are received at the opposite ends in time of the period of production in relation to which they are paid.

On this ‘classical’ notion of ‘costs’ as ‘quantities of things used up in production’, ‘cost had to be measured in order to compare it with product and thus determine whether the product contains a surplus over and above cost’ (pp. 25–6). The Petty perspective is also attributed to the Physiocrats, though for Quesnay and the earlier members of his school ‘the idea of cost is not necessarily linked up to that of price or value’. Sraffa then traces this notion of physical surplus, which turns on the idea that ‘producing meant to increase material weight’ (p. 26), to real-world circumstances. The calculation of the surplus ‘without introducing the disturbing element of price’ is possible only where input and output are homogeneous:

We can see how the Physiocrats came to hold this view. Measuring both the product and the cost in physical amount it is obvious that in agriculture, say in a corn farm, the amount of corn produced is greater than the amount used for seed and for subsistence of the workers. But in industry such a calculation leads to opposite results: e.g. in a spinning mill the amount, in weight, of the yarn produced is necessarily smaller than the weight of the cotton consumed. But apart from this absurdity, it is no doubt true that in agriculture, owing to the identity in the quality of the product and of the materials used up in production, the comparison for the calculation of the surplus is possible to some extent without introducing the disturbing element of price for measuring the quantities: whereas in industry the quality of the two things is so fundamentally different that only their values can be compared. The idea of the ‘net produce’ or surplus product, regarded as a difference between an amount of goods advanced (consumed) in production and the larger amount of goods produced is the corner stone of the physiocratic systems.

(pp. 26–7; emphasis added)

Now, though the strict Physiocratic position that ‘only agriculture produces a net surplus … was soon discarded, the notion of the surplus product plays an important part of the classical economics’ (p. 27). Smith, however, was ambiguous regarding the nature of costs23 giving rise both to the perspective of J.B. Say running along embryonic ‘Marshallian’ lines, and that of Ricardo, who — in contrast with Say — ‘reduces cost to a single element, labour, with some doubts as to whether to include the services of capital in addition to the labour that has produced the capital goods and who definitely excludes rent from cost’ (p. 36). For Ricardo,

all considerations about the pleasantness and unpleasantness of labour are irrelevant to this question. Workers are paid in exact proportion to what is required to keep them alive and efficient and thus to enable them to produce: the amount of wages necessary for this object is completely independent of the different sacrifices made by workers in different trades. Of course in trades in which greater efforts are expected higher wages will be paid, but this only to the extent that the greater effort requires a greater amount of food in order to be accomplished. But insofar as wages are different in different trades, this arises always only from the necessity of enabling the workers to accomplish the efforts, and not from the necessity to induce them.

(pp. 36–7)

A constant corn wage is thus central to the picture:

Wages are kept at what Ricardo calls ‘their natural level’ by the tendency of population to increase: it is no use paying to the workers more than the natural wage, because they will use the additional income to increase their numbers, and the competition of the newcomers will bring wages back to the natural level.

(p. 37)24

(Admittedly, ‘the natural level of wages is not fixed once and for ever: but it changes very slowly, with the changes in the habits of the people, and not with temporary fluctuations in the supply and demand of particular classes of workers.’) If followed that, for Ricardo,

labour is the ultimate constituent of cost not because it represents the human element in production, but only because it has necessarily used up a given amount of capital as its wages, and this amount must be replaced out of the price fetched by the product. Profits being proportional to capital and capital being reduced entirely to wages as direct and indirect labour, they affect according to Ricardo in the same proportion all the different commodities and therefore do not affect relative exchange values.

(p. 38)

Ricardo subsequently recognized difficulties in that differential values emerged with differential capitals, but ‘in this again he did not regard it as entering in the form of a human element, as abstinence, but only as time lost by capital goods in one employment, while they might have been properly employed elsewhere to support labour’ (p. 39).25

5 The Marxian input

Where in all this does Marx make an appearance? By way of general background, it should be mentioned that Sraffa adopted a perspective on the development of economics in general and the nineteenth century in particular that is entirely Marxian in its emphasis on ideology.26 This fact emerges clearly in the Cambridge Lectures. For example:

There are opposite interests which support either one solution [to social problems] or the other and they find theoretical, that is universal, arguments in order to prove that the solution they advocate is comfortable to natural laws, or to the public interest, or to the interest of the ruling class or to whatever ideology which at the particular moment is dominating.

(PSP, D2/4, p. 2; emphasis added)

Similarly: ‘A further disturbing element is that in the background of every theory of value there is a theory of distribution … and often theories of distribution in their turn are meant not so much as a means of analysing the actual process through which the product is distributed between different classes, as for showing either that the present system is wrong and should be changed, or that it is right and should be preserved. Thus an analysis of what is the theory becomes a form of propaganda for what [it] ought to be’ (p. 4; emphasis added).

The development of theory is also said to reflect environmental factors — in Ricardo’s case the clash between landlords and others (both capitalists and labourers); in the post-Ricardian period, the increasing importance of the conflict between manufacturing employers and labour (p. 10). There is reference to the use made of Ricardo’s value theory by Thompson and Hodgskin, who had understood it as maintaining that labour quantity is the ‘only cause of value’ — whatever qualifications ‘may have been in the back of [Ricardo’s] mind, as expressed in footnotes and correspondence’ — a perspective that in Ricardo’s own day favoured manufacturers (employers and labour) against landlords, but after his death, labour alone (p. 11). The use of ‘orthodox Ricardian economics’ in this ‘unexpected way’ led to a reaction by Torrens, McCulloch, Senior, and J.S. Mill (pp. 12–14), though ‘the prestige of the Ricardian theory was far too great to enable it to be discarded altogether as being, in the circumstances, definitely mischievous’ (p. 12).27 Thus the English Ricardians, Torrens and McCulloch,

made a whole series of attempts in order to save the substance of the labour theory of value and at the same time taking away from it, its anti-capitalist implications’. And ‘thanks to the influence of Mill, the Ricardian theory, though considerably qualified and changed in important respects, dominated political economy up to the seventies.

(p. 14)

Most significant is the view taken of the development of marginal utility theory as a defensive reaction against Marx. Specifically,

Marx published the Capital [sic] in which his critique of capitalism is entirely based upon Ricardo’s theory of value, although of course he interpreted it in an entirely different way from the earlier Utopian socialists. On the other hand, the entirely new theory of value, based exclusively on marginal utility, was found [sic] (or invented) almost simultaneously and independently by Jevons in England, Menger in Austria, and Walras in France.

(pp. 14–15)

Various precursors — Cournot, Dupuit, and Gossen — were considered ‘cranks’ and ‘amateurs’ (p. 15). The success of utility theory and its further development by professional economists entailed an ‘absolute break in the tradition of Political Economy’ (p. 16) and was explicable in ideological terms, Sraffa referring to,

that close relation between the emerging of Marxism and the extraordinarily ready acceptance which the theory of m.u. [sic] [received] amongst orthodox economists … Conservative minded people were only too glad to seize the opportunity of getting rid of the labour theory of value, notwithstanding the enormous authority it derived from the tradition of classical economists.

(pp. 15–16)

So much for Sraffa’s Marxian historiographical outlook turning on ideology and environmental considerations, an outlook also conspicuous in Dobb 1973 and Bharadwaj 1978.

Sraffa’s familiarity with, and sympathy for, Marx in fact goes back to his early years, before his first travels to Britain in 1920 (see, e.g., Roncaglia 1998). Potier observes regarding 1924–25 that ‘it is not easy today to determine precisely what might have been Sraffa’s opinion of Marx’s Capital’ (1991, p. 16),28 but it may be significant that, at the close of his 1926 paper on costs after discussing credit and the like, Sraffa concludes in Marxian terms: ‘these are mainly aspects of the process of diffusion of profits throughout the various stages of production and of the process of forming a normal level of profits throughout all the industries of a country’ (1926, p. 550).29 We also know that, in the mid 1920s, the research culminating in PCMC was set in motion, Sraffa drawing on notes from that period when preparing the work (see the Piero Sraffa Papers) and that by the late 1920s its ‘central propositions had taken shape’ (Sraffa 1960, p. vi).30 Now Sraffa is on record as expressing his indebtedness to Marx at this time:

Sraffa told us [in June 1973] that he would not have been able to write Production of commodities by means of commodities if Marx had not written Capital. It is clear, he told us, that the work of Marx strongly influenced him, and that he felt more in sympathy with him than with those he called the ‘camouflagers’ [les camoufleurs] of capitalist reality.

(Dostaler 1982, p. 103; my translation: see also 1986, p. 468)31

More specifically: ‘Sraffa considered that his model described some aspects of the same reality that Marx had described, a reality characterized by class antagonism between workers and capitalists, the exploitation of the first by the second’; and his equation r = R(1 − w) derived from the standard commodity was seen by Sraffa to be the equivalent of Marx’s rate of exploitation, for it was

immaterial whether this reality is expressed in terms of the worker working x hours to reproduce his labour-power and y hours to create surplus-value for the capitalist, or in terms of a physical surplus, R, the distribution of which constitutes the stake [l’enjeu] in a struggle expressed ‘algebraically’ by the famous equation r = R(1 − w).

And it will indeed be recalled that the role of his standard system was, Sraffa tells us, to ‘give transparency to an [actual] system and render visible what was hidden’ (1960, p. 23), a formulation that conveys Marx’s description of his own procedures in the transformation context, where he applied the methodological rule that ‘all science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided’ (1962 [1894], p. 797), seeking to avoid errors of interpretation flowing from appearance — that ‘normal profits themselves seem immanent in capital and independent of exploitation’ (p. 808), and that wages, profit and rent are ‘three independent magnitudes of value, whose total magnitude produces, limits and determines the magnitude of the commodity-value’ (p. 841).32

The informal record of Sraffa’s position that PCMC was inspired by Marx’s perspective on exploitation should be read together with Sraffa’s insistence that the main features of his own work — concerned with the problem of a given physical surplus to be distributed to assure a uniform profit rate — reflect Ricardo’s ‘method of approach’ of the Principles, not only the passing phase of the Essay, which ‘rendered distribution independent of value’ (above, pp. 285–6). Sraffa himself emphasized that Marx’s critique of capitalism turned on Ricardian value theory (above, p. 306); and we recall that Ricardo’s profit-rate formula (assuming only variable capital) is indeed identical with Marx’s rate of exploitation. Sraffa, therefore, emerges as fully in the Marxian tradition, keeping in mind always his allowance for the profound influence on Marx flowing from Ricardo.

* * *

We have also seen that Sraffa, in his Cambridge Lectures, provided a historiographical perspective relating to the Physiocrats and the British classics, Ricardo in particular, and traced back to Petty, in terms of surplus, wherein cost is perceived as ‘quantities of things used up in production’, and surplus as the excess in physical terms over such cost, thereby avoiding ‘the disturbing element of price for measuring the quantities’ (above, p. 303). Strangely, Sraffa himself — in lecturing on the surplus approach — made no mention of Marx; yet it is indubitably Marxian historiography that he was expounding. For Marx had portrayed Petty precisely as did Sraffa, considering him to be ‘the father of English political economy’, and citing precisely the same passage as Sraffa (above, note 22) — where Petty ‘proposes to speak “in Terms of Number, Weight or Measure” and leave aside arguments that depend upon the mutable Minds, Opinions, Appetites, and Passions of particular Men’ (Marx 1970 [1859], p. 53). Also relevant are Marx’s references to various ‘striking passages’ by Petty, including the subsistence wage (1954 [1862–3], p. 346) and to the notion of corn surplus, both (we have seen) alluded to by Sraffa:

Suppose a man could with his own hands plant a certain scope of land with Corn, that is Digg, or Plough, Harrow, Weed, Reap, Carry home, Thresh, and Winnow so much as the Husbandry of his Land requires; and had withal Seed wherewith to sowe the same. I say, that when this man hath subducted his seed out of the proceed of his Harvest, and also, what himself hath both eaten and given to others in exchange for Clothes, and other Natural necessaries; that the remainder of the Corn is the natural and true Rent of the Land for that year.

(pp. 346–7; Marx’s emphasis; cf. p. 177)33

And, similarly, Marx had adopted precisely the same perspective on the Physiocrats as did Sraffa:

In manufacture the workman is not generally seen directly producing either his means of subsistence or the surplus in excess of his means of subsistence. The process is mediated through purchase and sale, through the various acts of circulation, and the analysis of value in general is necessary for it to be understood. In agriculture it shows itself directly in the surplus of use-values produced over use-values consumed by the labourer, and can therefore be grasped without an analysis of value in general, without a clear understanding of the nature of value.

(p. 46; cf. pp. 48–9, 50)

The physical basis of surplus-value is this ‘gift of nature’, most obvious in agricultural labour, which originally satisfied nearly all human needs. It is not so in manufacturing labour, because the product must first be sold as a commodity. The Physiocrats, the first to analyse surplus-value, understand it in its natural form (1971 [1862–3], pp. 115–16).

The corn-profit interpretation thus falls into the Marxian reading. And this seems to be confirmed by the 1960 account. For Sraffa notes a parallelism between Ricardo’s Essay of 1815 — as he understood it — and the Physiocrats:

Ricardo’s view of the dominant role of the farmer’s profits thus appears to have a point of contact with the Physiocratic doctrine of the ‘produit net’ insofar as the latter is based, as Marx has pointed out, on the ‘physical’ nature of the surplus in agriculture which takes the form of an excess of food produced over the food advanced for production; whereas in manufacturing, where food and raw materials must be bought from agriculture, surplus can only appear as a result of the sale of the product

(1960, p. 93)

6 Summary and concluding remarks

We have gone some way towards confirming Sraffa’s Marxian orientation concerning the place of Ricardo in the development of the history of economics, in particular with reference to the significance of the surplus conception. In fact, PCMC itself was designed, so it appears, to convey the essence of Marx’s exploitation doctrine. Now Marx had himself learned much of his economics — including the rate of surplus value based on a mean-proportions measure — from Ricardo. This interdependence — it has elements of a dog chasing its tail (Chidem Kurdas, in correspondence, 4 May 1997) — was appreciated by Sraffa, who emphasized the dependence of Marx’s theory of exploitation on Ricardian value theory.34