Ricardo’s standard of value

A new proposal

Christian Bidard*

1 The question of value

Ricardo’s quest for an invariable standard of value aims at identifying the origin of a move in relative prices by looking at the evolution of the conditions of production. When, after a change of techniques, the exchange ratio between corn and iron decreases from 2:1 to 1:1, the cause of the variation may be either a deterioration in agricultural production (less fertile lands are cultivated) or a technical improvement in metallurgy, or any combination of these motives. Though the change in relative prices is the same in all cases, the economic consequences of these phenomena differ drastically. That is why Ricardo asked for a measure of absolute values:

No one can doubt that it would be a great desideratum in Political Economy to have such a measure of absolute value in order to enable us to know, when commodities altered in exchangeable value, in which the alteration in value had taken place.

(Ricardo, 1823b)

A theory of value (i.e. absolute value) goes beyond the question of relative prices. In Ricardo’s views, political economy is a science that explains the market phenomena by relying on a deeper understanding of the causes that determine them. Its tools and ways of reasoning cannot be restricted to market magnitudes: for their specific purposes, economists are led to define the values of iron in Portugal and England, even if these commodities are not exchanged one against the other. This conviction is the basis for Ricardo’s contempt of the merchants’ pretensions, merchants who are ‘notoriously ignorant of the most obvious principles of political oeconomy’ (Ricardo, 1810b). Suppose that the knowledge of absolute values shows us that the value of corn, which is a measure of its difficulty of production, has doubled, while that of iron is unchanged. The conclusion sheds light on the origin of the variation in relative prices and, more importantly, on the dramatic evolution of the economy. If, on the contrary, the measure of values indicates that the difficulty of production of corn is unchanged and that of iron is halved, the economy is moving on a progressive path. Therefore, beyond an explanation of relative prices, absolute values can be used for intertemporal comparisons (measure of technical change in each industry) or, at a given moment of time, for a comparison between countries. In a well-known example drawn from Chapter 7 of Principles (1817), Portugal is assumed to be more productive than England for both wine and cloth, with a relative advantage for wine and a relative disadvantage for cloth. The situation is represented in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1

| Portugal | England | |

| absolute value of wine | 80 | 120 |

| absolute value of cloth | 90 | 100 |

Here, Ricardo used labour values: in Portugal, eighty units of labour are incorporated into a pipe of wine. The labour content of a commodity is the typical example of a measure of absolute values: to claim that a pipe of wine requires eighty units of direct and indirect labour is to estimate its difficulty of production, independently of and prior to any comparison with another commodity. Were exchangeable values equal to relative labour values, that measure would be the final answer. However, even if Ricardo adopted labour value in the Principles and showed the efficiency of the approach, he remained worried about the shaky foundations of his construction. That is why he came back time and again to the concept of absolute value and, slightly discouraged, eventually expressed doubts on the very possibility of finding more than a proxy. In his very last manuscripts (1823a, 1823b), he adopted an axiomatic approach and tried to define the ideal characteristics of an invariable standard, the tool by which absolute values are or would be measured.

In this paper, we follow Ricardo’s endeavour, propose an interpretation and construct a standard of value that intends to be a partial answer to Ricardo’s problem. The construction and the definition of these absolute values are foreign to the notion of labour value. Beyond the short-term evolutions of market prices, relative prices move in the long run with either distribution or change of methods. Sraffa (1960) built an invariable standard of value in the face of variations in distribution. We shall not discuss it for two reasons. First, our failure to understand the meaning of that construction is, upon academic standards, a sufficient justification for not entering into a debate. We shall, however, adopt Sraffa’s ingenious trick in order to generalize our own approach from a corn model to a multisector economy. Second, the stress in Ricardo’s works is on technical change more than distribution. In order to isolate the influence of technical change, we freeze distribution by assuming that each worker receives a given real wage. When every unit of labour is replaced by its equivalent wage basket, explicit labour disappears from the input matrix. This once done, the reference to the labour theory of value falls of necessity, not the question of an absolute value: if the production of iron in Portugal requires less of every input than in England, it can be said that iron is easier to produce there and that its absolute value is smaller (there remains, however, to define how much it is smaller). The argument shows that the theory of absolute values cannot be identified with that of labour value. Note that in Ricardo’s (1823a and b) general approach, the notion of absolute value is strongly connected with the definition of an invariable standard, and that the notion of a standard basket leaves no room for the labour theory of value.

In Section 2, we summarize the evolution of Ricardo’s thought on value. Our reading is influenced by Sraffa’s interpretation (1951) but differs from it on several points. Section 3 builds a measure of value in the face of technical change in successive steps. The first steps deal with a simple economy, with corn as the unique basic commodity. The important lesson derived from this examination is that, contrary to Ricardo’s claim, the question of value cannot be identified with the search for, or the definition of, an absolute standard: we introduce the notion of sliding standard as a tool to measure absolute values. Section 4 borrows Sraffa’s idea of a homothetic basket to extend the construction to multisector economies.

2 The embodiments of value

What is the meaning of the notion of difficulty of production? How can that difficulty be measured? The question appears early in Ricardo’s work in conjunction with the concept of standard commodity, but the answers evolve. Ricardo’s (1810a) initial position was that precious metals have a permanent value, an advantage that has made them adopted as universal means of exchange. However, the invariance property attributed to gold is mainly conventional. The necessity to clarify the concept of value led Ricardo to return to the question in the Essay (1815).

Sraffa’s idea that the Essay’s reasoning is based on a model in which agriculture constitutes the basic sector is illuminating. The corn model eliminates relative prices and makes possible a physical measurement of distribution. However, we do not follow Sraffa when he considers that the question of value itself is evacuated from the corn model. On the contrary, the model makes the difficulty of production, as it is measured by the ratio between the stock of seeds and the product, immediately visible. Let us remind the reader that, at Ricardo’s time, it was not uncommon to estimate agricultural productivity in terms of returns per seed rather than per acre: a modern estimate based on evidences related by A. Young, a British traveller and a specialist of agriculture, has led historians to conclude that, at the time of the French Revolution, the productivity per seed was about 5:1 in France against 12:1 in England. Such a measure was prosaically inspired by the necessity for the peasants to withdraw the amount of future seeds from the annual crop, a requirement that was hard to meet in case of food shortage. Returning to economic theory, the difficulty of the production of wheat, that is the very question of value, is at the heart of Ricardo’s reasoning, and it is that point that Malthus failed to understand. In the controversy that followed the publication of the Essay, Malthus argued that, if the relative price of wheat rises, the same happens to the rate of profit of the farmer. Ricardo’s answer (letter dated 14 March 1815) must be read with care:

I cannot hesitate in agreeing with you that if from a rise in the relative value of corn less is paid for fixed capital and wages, — more of the produce must remain for the landlord and farmer together —, this is indeed self evident, but is really not the matter in dispute between us, and I cannot help thinking that you overlook some of the circumstances most important connected with the question.

(Ricardo, 1951–73, WCDR, vol. VI, p. 189)

Ricardo went back from the phenomenon (the rise in the relative price of wheat) to its cause, which is the increasing difficulty of production:

My opinion is that corn can only permanently rise in its exchangeable value when the real expences of its production increase. If 5000 quarters of gross produce cost 2500 quarters for the expences of wages &c., and 10000 quarters cost double or 5000 quarters, the exchangeable value of corn would be the same, but if 10000 quarters cost 5500 quarters for the expences of wages &c., then the price would rise 10 pct because such would be the amount of the increased expences.

(ibid.)

Ricardo’s reasoning is based on the notion of value or real price (which is the meaning of the word ‘price’ in the quotation). The exchange value of wheat grows because its real price rises by 10 per cent between economies represented, respectively, by the methods 5,000 qr. wheat → 10,000 qr. wheat and 5,500 qr. wheat → 10,000 qr. wheat:

[T]he cause of the rise of the price of corn is solely on account of the increased expence of production.

(ibid.)

The abandonment of the corn standard after the Essay resulted from the extreme specificity of the corn model: even in agriculture, the product and the capital are not homogeneous. The theory of labour value elaborated during the preparation of the Principles (1817) frees itself from the homogeneity hypothesis and constitutes the answer adopted in that book. Value is no longer embodied in a reference commodity, and the amount of direct and indirect labour is a self-sufficient measure. Consequently, the theme of the invariable standard was withdrawn.

In the third edition of the Principles , published in 1821, the chapter On Value was reorganized, reformulated and developed. This was necessary after the publication of Malthus’s book to which Ricardo replied in his Notes on Malthus’ principles (1820). Similarly, it was in reaction to The measure of value that Ricardo wrote a draft of Absolute value and exchangeable value (1823a). He was then fully aware of the analytical defects of labour value: (i) prices are not proportional to the labour contents; (ii) relative prices, but not labour values, are affected by changes in distribution; and (iii) for a given quantity of labour, the price depends on the delay of production. The theory of labour value was henceforth expressed in terms of the best possible approximation. Depending on whether one insists on the imperfection of approximation or its quality, the last writings of Ricardo seem to distance him from, or to draw him close to, the notion of labour value. In our view, the essential point is less the conclusion than the approach adopted in these manuscripts. In his last examination of the problem, Ricardo attempted an analysis ab ovo of the question of value while embarking on a path reminiscent of the Essay. Though Ricardo’s failure is often attributed to the impossibility of resolving the jigsaw of heterogeneity, the thesis we uphold is that it is due to a more profound reason that has not been identified up to now.

3 A standard for corn economies

This section proposes the construction of a standard of value when the conditions of production change. In order to neutralize the effects of distribution, the real wage is given and incorporated into the inputs. We compare two economies in which corn is the only basic commodity: E1 is the initial economy, E2 the economy after technical change. In this simple framework, our aim is to show that the notion of an absolute value is based on the notion of standard of value but need not be identified with the definition of an invariant standard. ‘Value’ always means absolute value, except when otherwise specified.

3.1 Corn as an absolute standard

Consider two economies in which corn (= commodity C) is the only basic commodity, commodity N being non-basic. Let there be a technical change in the production of the non-basic (‘non basic technical change’):

Table 13.2

| E1 | E2 | |

| 5,000 qr. corn → 10,000 qr. corn | 5,000 qr. corn → 10,000 qr. corn | (1) |

| 400 C ⊕ 300 N → 1,000 qr. N | 200 C ⊕ 200 N → 1,000 qr. N | (2) |

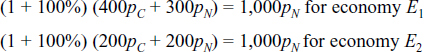

Its difficulty of production being constant, corn is the invariable standard of value. By convention, we set that the difficulty of production of corn as it is represented by relation (1) is such that the value of a quarter of corn is one unit of value (this is but a normalization of the unit of value, in the same way as the unit of measure for labour values may be the hour or the day). In view of the production relationships (2), commodity N is easier to produce in the second economy. The rate of profit r = 100 per cent being determined by the conditions of production in agriculture, the price equations corresponding to the physical relations (2) are, respectively, written

from which the relative prices follow: (pN/pC)1 = 2 > (pN/pC)2 = 2/3. The decline in the relative price of N reflects a decreasing difficulty of production. However, when the relative price pN/pC is only known, its fall from 2 to 0.67 provides no hint as to the origin of the change: it might stem from an improvement in the production of N or a degradation in the production of C. The definition of values aims at making the cause of the variation visible. In the present case, as the conditions of production of corn are unchanged, we set:

![]()

(letter V is for value, the upper index for the good and the lower index for the economy.) An economist who has no direct knowledge of the conditions of production can read in these figures the evolution of relative prices, from (VN:VC)1 = 2 to (VN:VC)2 = 0.67, and the reason for their variation: as the value of corn is unchanged, whereas that of N has decreased, commodity N is easier to produce in the second economy. The economist knows more than the merchant …

That construction adopts the Ricardian hypothesis that the relative prices do reflect the relative difficulties of production. Once the value of corn has been determined, the values of the other commodity(ies) are calculated in order to fit with relative prices: by construction, relative prices and relative values are identical.

3.2 Ricardo on measure

We consider now a change in the production of corn (‘basic’ technical change). To start with, corn is supposed to be the only existing commodity: the economies E3 and E4 are described by the production relationships shown in Table 13.3.

Table 13.3

| E3 | E4 | |

| 5,000 qr. corn → 10,000 qr. corn | 5,500 qr. corn → 10,000 qr. corn | (3) |

The notion of relative price has no meaning in such a framework, nor that of value, and our purpose is precisely to give an expression, in terms of value, to the increasing difficulty to produce corn. This is simply achieved by stating that the value of corn is higher in E4 (V4C > V3C). Then, an economist who has no direct knowledge of the conditions of production learns, directly from the values, that the production of corn has become more difficult. In quantitative terms, what is the exact increase in the difficulty of production after technical change? There is some part of arbitrariness here, but, in order to fit with Ricardo’s numerical example in the letter to Malthus quoted in Section 2, let us identify the difficulty of production with the amount of seeds necessary to obtain two quarters of corn (the artificial reference to a gross product equal to two quarters reminds us that the definition of the unit of value is conventional). Then V3C = 1 and V4C = 1.1, so that the difficulty of production rises by 10 per cent from E3 to E4.

The solution to the question of value is trivial in this example, but the simplicity of the framework makes a contradiction appear in Ricardo’s thought. Ricardo (1823a) did not distinguish the measure of value from the definition of an absolute standard, i.e. from the search for a commodity with a constant difficulty of production:

The only qualities necessary to make a measure of value a perfect one are, that it should itself have value, and that that value should itself be invariable, in the same manner as in a perfect measure of length the measure should have length and that that length should be neither liable to be increased or diminished; or in a measure of weight that it should have weight and that such weight should be constant.

(Introductory sentence, Absolute value and

exchangeable value, Ricardo, 1823a)

Ricardo stated a general methodological principle in the introductory sentence of the manuscript because he reconsidered the problem of value from its very foundations. The principle itself corresponds to Ricardo’s permanent conviction (‘A measure of value should itself be invariable’, The high price of bullion (1810a), WCDR, vol. III, p. 52) and is in accordance with the physical (Galileo, Newton) and philosophical (Kant) conceptions of his time. Our point is that the principle is and must be violated for the measure of value: even in a onecommodity economy, corn has not an invariable value after a technical change. Similarly, in a multisector economy with technical progress in all industries, no commodity or basket of commodities has a constant difficulty of production.

Sraffa’s contribution made clear that the passage from one to several commodities is a serious obstacle in the definition of a standard basket, and most economists tend to believe that the main difficulty in Ricardo’s quest is located here. Our opinion, on the contrary, is that the origin of Ricardo’s failure is rooted in his methodological principle: namely, the improper identification of the measure of absolute values with the characterization of an invariable standard. The approach led Ricardo to make reference to activities such as shrimping (which is not affected by technical progress) and, finally, to accept a measure of value in terms of everlasting elementary labour.

Is an alternative way of thinking conceivable? Yes, if the idea of absolute value is dissociated from the search for an invariable standard. In a world of generalized technical change, ‘the only qualities necessary to make a measure of value’ are that the change concerning the commodity or basket of commodities chosen as standard is easily measurable. That commodity is a sliding standard (sliding, because its value need not be constant); then, the variations of the other commodities are obtained by comparing their value with that of the sliding standard. In somewhat grandiloquent terms, the approach we propose is based on a relativity principle: to calculate the speed of a cyclist, it is not necessary to be on the land; it suffices to observe her from a boat, provided one knows the speed relative to the boat (the change relative to the standard) and the drift of the boat (the change in the standard). That procedure is the only possibility in the absence of a fixed point on the mainland.

3.3 Corn as a sliding standard

To combine the two features we have examined successively, we consider two economies in which corn is the only basic commodity, and technical change affects both the production of corn and that of a non-basic. The data are shown in Table 13.4.

Table 13.4

| E1 | E5 | |

| 5,000 C → 10,000 C | 5,500 C → 10,000 C | (4) |

| 400 C ⊕ 300 N → 1,000 qr. N | 200 C ⊕ 200 N → 1,000 qr. N | (5) |

Even if the method of production of the non-basic was unchanged, that commodity could not be taken as an absolute standard of value because its production requires corn, which has become more difficult to produce in E5. To determine the values, we first proceed as in Section 3.2 and calculate the evolution in the production of corn from one economy to the other. The result is V1C = 1 and V5C = 1 = 1.1: corn is a sliding standard, and its difficulty of production has risen by 10 per cent. Next, as in Section 3.1, we consider that the relative price and the relative value, i.e. the ratio of values, coincide in each economy. The calculation of relative price in each economy separately leads us to V1N:V1C = 2 for economy E1, as already seen, and to V5N:V5C = 0.57 for economy E5. On the whole, the absolute values are V1C = 1, V5C = 1.1, V1N = 2 and V5N = 1.14. It turns out that the difficulty of production of the non-basic is smaller in E5, because the slight degradation in the production of corn is more than compensated by a significant improvement in that of N. The absolute values of both commodities are well defined, in spite of the absence of an absolute standard.

4 Multisector economies

Let us now extend the construction to the comparison of multisector basic economies. To compare two single-product economies E1 and E2, represented by the input matrices A1 and A2, we first identify a sliding standard: it is a commodity or basket of commodities, the difficulty of production of which, as it is represented by the amount of inputs necessary for its production, evolves but can be followed precisely.

Sraffa’s device (1960, Chapter IV) can be adapted to this problem. To produce a given basket represented by the row vector s, the input baskets amount to sA1 and sA2, respectively. For an arbitrary basket s, these baskets are not comparable. However, for some adequately chosen basket s, it may be the case that they are proportional:

| (6) |

As the production of such a basket s requires α times fewer inputs in the second economy, it can be said that its value is α times smaller in E2 than in E1. That basket plays a role analogous to corn in the previous section and defines the sliding standard. The absolute values of each commodity are then calculated by means of the following procedure:

• The value of the standard s decreases by the factor α defined by equality (6).

• In each economy, the vectors of absolute values and those of relative prices are proportional.

• The value of a numeraire, which may or may not be the standard basket, in the first economy is equal to one (normalization convention).

Let us illustrate the construction by means of a numerical example concerning the economies represented by the input matrices A1 and A2:

![]()

An immediate calculation shows that the inputs required for producing basket s = 1X ⊕ 2Y amount to sA1= 1X ⊕ 2/3Y and sA2 = 0.9X ⊕ 0.67, respectively; hence the equality sA2 = 0.9sA1: basket s is a sliding standard. The calculation of the relative price in each economy separately (1:1 and 3:1) shows that the vectors of values are written V1 = (λ, λ) and V2 = (3μ, μ). For a given X, the scalar μ is determined by the evolution of the value of the sliding standard, which is equal to 3λ in E1 and to 5μ in E2: the equality 5μ = 0.9 × 3λ determines μ = 0.54λ. If we adopt the inessential convention that the value of the first commodity in the first economy is equal to one, we have λ = 1. Eventually, it turns out that the absolute values are (1, 1) in economy E1 and (1.62, 0.54) in E2: the difficulty of production of the first good has increased by 62 per cent, whereas that of the second has decreased by 46 per cent.

The construction of a standard basket is not a complete answer to Ricardo’s ambition. First, it is only concerned with technical change, not distribution. Second, the standard is defined for a pair of economies. The existence of a ‘universal’ standard for all economies is highly improbable, and a restriction of the initial programme seems realistic (Bidard, 2004, Chapter VII). With regard to Sraffa’s position (Introduction, 1951; Production, 1960), we consider that the identification of a corn model in the Essay and its formal extension to multisector economies constitute brilliant interpretations. However, we strongly disagree with the idea that the corn model eliminates the problem of value when, on the contrary, it isolates it in its purest form (Section 3.2). We also reject the identification between the concepts of absolute value and embodied labour, an equality set explicitly by Dobb, who collaborated with Sraffa for the edition of Ricardo’s works:

In particular I think we [Dobb and Sraffa, C.B.] conclusively establish […] that there was no ‘weakening’ of Ricardo’s enunciation of the labour theory as time went on […] [The unpublished manuscript on ‘Absolute value and exchangeable value’ shows that Ricardo] was at the last still exercised with a notion of an Absolute Value (= embodied labour) as something distinct from, but underlying, exchange-value: in fact the notion and the distinction is more explicit in this last paper than in the ‘Principles’.

(Correspondence, Dobb to Th. Prager, 23 December 1950;

quoted from Pollitt, 1990, p. 524)

These disagreements lead us to a different understanding of Ricardo’s last works.

4 Conclusion

It is often claimed that the difficulty encountered in defining a standard of value in the presence of a change of technique stems from the interindustrial relationships and the heterogeneity of commodities. The direct cause of Ricardo’s failure in his quest has been found elsewhere: given his methodological premises on measurement, Ricardo associated the notion of absolute value with that of an invariable standard, which does not and cannot exist in general. This is why Ricardo, after having examined several theoretical alternatives, finally reverted to a measure in terms of labour. Our proposal is to abandon Ricardo’s premises and to use a sliding standard to measure absolute values.

Some theorists refer to Ricardo’s reflections on value as an example of the classical economists’ mistakes. Ricardo’s problem is deeper than it may appear to a superficial examiner and constitutes the archetype of most problems concerning the measurement of change. The difficulty in understanding Ricardo is that his level of abstraction is higher than is the norm in economics.

Note

* University of Paris Ouest-Nanterre-La Défense, Economix.

References

Bidard, C. (2004), Prices , reproduction, scarcity, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Pollitt, B.H. (1990), ‘Clearing the path for Production of commodities by means of commodities: notes on the collaboration of Maurice Dobb in Piero Sraffa’s edition of The works and correspondence of David Ricardo’, Essays on Piero Sraffa, Bharadwaj K. and Schefold B. eds, Unwin Hyman, London, pp. 516–28.

Ricardo, D. (1809), ‘The price of gold. Three contributions to the Morning Chronicle, The works and correspondence of David Ricardo [WCDR]’, vol. III: ‘The price of gold’, 15–21; First reply to a ‘Friend of bank-notes’, 21–7; Second reply to a ‘Friend of bank-notes’, 28–33.

Ricardo, D. (1810a), ‘The high price of bullion, a proof of the depreciation of bank notes’, WCDR, vol. IIIf, 47–99.

Ricardo, D. (1810b), First letter to the Morning Chronicle on the Bullion Report, WCDR, vol. III, 131–9.

Ricardo, D. (1815), ‘An essay on the influence of a low price of corn on the profits of stock’, WCDR, vol. IV, 9–41.

Ricardo, D. (1817), ‘On the principles of political economy and taxation’, WCDR, vol. I.

Ricardo, D. (1820), ‘Notes on Mathus’s principles of political economy’, WCDR, vol. II.

Ricardo, D. (1823a), ‘Absolute value and exchangeable value (a rough draft)’, WCDR, vol. IV, 361–97.

Ricardo, D. (1823b), ‘Absolute value and exchangeable value’ (later version, unfinished),WCDR, vol. IV, 398–412.

Ricardo, D. (1951–73), The works and correspondence of David Ricardo [WCDR], edited by Sraffa, P. with the collaboration of M.H. Dobb, 13 vols., Cambridge University Press,Cambridge.

Sraffa, P. (1951), Introduction to the works and correspondence of David Ricardo [WCDR], vol. I, xiii–lxiii.

Sraffa, P. (1960), Production of commodities by means of commodities, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.