Selecting Methods or Tools

Each researcher must decide which tools to use in order to answer study questions, how the tools should be implemented to the best effect, and who should implement them. The decisions researchers make about which tools to use will depend on the research questions, the training and skills of the research team, and the amount of time and money available to conduct research in the study setting. How much researchers actually know about the study setting also influences the tools they use for data collection. Those with prior experience in the setting, or who are already members of the study community, generally know more than novices or researchers new to the community and thus would resort less to exploratory approaches.

Further, the ability to engage in informed observation and interviewing and the sequencing of data collection activities is enhanced by being able to speak the local language. A student who is learning Swahili, Wolof, or Spanish in the field might like to begin with a few simple, structured interview questions that require limited mastery of the language (for example, asking vendors in a market where their products come from, asking teachers what languages their students speak, or asking people in a park where they live and how often they come there). Experienced researchers who speak the language used in the study site or researchers working in partnership with informed residents might not require these preliminary activities and can begin their qualitative research immediately by interviewing local experts on the study topic.

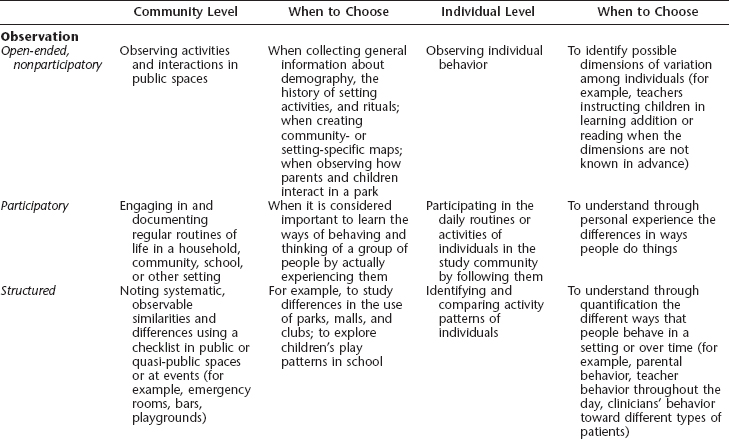

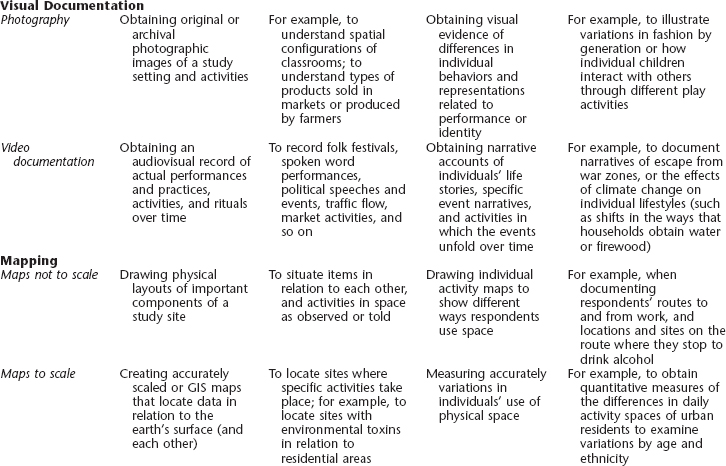

Table 4.3 summarizes the main types of qualitative research tools and provides some general suggestions as to when to use them in order to understand either the broader context of individual beliefs and behaviors (at the community level) or the individual perspective. Ideally these methods are complementary. It is convenient to introduce them sequentially, beginning with open-ended observations, interviews, and mapping, supplemented with various forms of cultural consensus modeling and photography. The community-level data provide the framework and information to move to semistructured observations and interviewing with specific samples of activities and individuals. In a true qualitative field study, participant observation (whereby the researcher observes and participates at the same time) and informal interviewing along with photographic documentation can occur throughout the life of the study, allowing the researcher to accumulate data on the community level. The data collected through these steps provide the basis for a qualitatively derived survey, the results of which can be explained with the qualitative data and by member checking, reviewing the results with members of the study community. The end result is an interpretive document or documentary that reflects both the views and voices of the study community (the emic perspective) and the theoretically framed analysis of the researcher (the etic perspective).

Table 4.3 Guide to Qualitative Research Tools

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- Can you identify any of the data collection methods described above that you would not feel comfortable implementing? Why? Which ones would you be most likely to choose, and why would you choose to apply them?

- Can you think of any situations in which you could not apply one of these approaches?

Use of Cameras and Digital Recorders in Qualitative Research

Photo and video cameras and digital recorders are useful in recording live situations and in-depth interviews. All three aids to data collection are visible and to some degree intrusive. However, if the researcher has a good and trusting relationship with the respondents, obtains permission to film or record, and has undergone review by an institutional review board to ensure human subjects' protection and the absence of such threats as loss of confidentiality (see the next section for more on this review process), it is usually possible to use all three tools. Researchers should be sensitive to the possibility that certain people may not like to be photographed for a variety of reasons, including the belief that photographs capture the soul of the person, a desire for privacy, and gendered rules that preclude photographing women. Thus researchers should always ask permission before taking photographs of people in a research setting. Researchers should also be prepared to describe the storage, analysis, use, and destruction of audiovisual materials after the study is done. Finally, if the audiovisual materials will be used in any scientific productions (for example, a film, photographic exhibit, publication, installation, or Web site), the individuals involved should be asked to sign a release form and offered a clear explanation, in their own language, of how the materials will be used and what, if any, consequences there might be for the respondent and his or her community. (Chapter Two offers full details on these issues.)

Ethical Issues in Data Collection

All studies, including qualitative studies, require a review and approval by institutional review boards (IRBs). IRBs are university- or community-based ethics committees that meet regularly to provide an independent review of ethical considerations related to a study and the protection of “human subjects” or respondents, as well as the communities or other settings in which the research will be conducted. For example, qualitative researchers often pay respondents or give them small gifts for taking the time to participate in interviews or surveys. These payments are considered to be incentives. Researchers usually determine the value of incentives based on prevailing rates for similar studies in the area, and by taking into consideration what incentives could have a possible coercive effect on individual respondents in the study. Incentive amounts are intended to cover the cost of time required to participate in the study. They should be substantial enough to attract volunteers for a study, and small enough to avoid being considered coercive, especially when respondents have modest or low incomes, may need additional sources of financial support, or might not feel that they can refuse voluntarily. Insights and guidance in the ethics of qualitative research with diverse populations can be found on the Web site of the American Anthropological Association (www.aaanet.org/ar/irb/index.htm), and in publications by Trimble and Fisher (2006) and Hoonaard (2002, 2011), among others.

Although all interview schedules should be approved by an institutional review board, it is also important for IRB members to understand that in qualitative research interviewers do not always know in advance what all the relevant questions may be. Thus it is often the case that the community-level in-depth or focus group interview protocol or the individual-level in-depth interview schedule that is submitted to the IRB consists of only a few open-ended questions.