Ready About: Don't Lose Your Bearings

Mark Berns has a flair for navigating treacherous waters.

A passionate sailor, Berns also heads Ready About, a consulting firm that guides companies through potentially disruptive changes, such as strategic realignments, mergers, and acquisitions.

Plans for organizational change often look lucrative on paper and meet resounding approval at the highest levels of management. But they can go awry when they fail to account for a company's intangible–but often most valuable–assets. These can include group or corporate culture, operational strategy, and trusted avenues of internal communication. It doesn't help matters if key employees resist the coming change because they resent the strategy or don't have enough information about what's going to happen.

“If culture is a company's DNA, acquisitions are a bit like gene splicing. You want to combine the best of both worlds so you don't end up with Frankenstein, Inc.”

–Mark Berns.b

Enter Ready About, named after the command a captain issues to make sure his crew is ready to chart a new course. Berns and his team help organizations thrive before and after big changes. They specialize in organizational strategy, team effectiveness, and mergers and acquisitions.

Whether brought into a company to manage change or keeping in close contact as a consulting partner, Ready About makes sure companies stay watchful of the “soft” assets that bring them value.

Berns himself has been involved in more than 100 acquisitions, and he's quick to emphasize the importance of culture in defining an organization. “I see culture as the story we tell about ourselves,” he says. “It's mission, vision, and our relationships with each other and the broader world. It's the all-out company effort to support a food pantry. It's even that we always dress casually and have muffins on Friday.”a

Quick Summary

- Ready About helps clients manage and survive large organizational changes such as mergers, acquisitions, and strategy realignments.

- Immersed in day-to-day operations, many companies lack the perspective to understand how organizational change will affect their soft assets, such as company culture and successful internal communication.

- Ready About's consulting emphasizes helping companies understand and monitor the health of these resources while managing operational or material change.

FYI: 83% of mergers fail to increase shareholder value.c

you can't do it alone

14 Leadership Challenges and Organizational Change

Some challenges of leadership and organizational change are quite new; others have been recognized for decades. In leadership, these issues are addressed relative to moral persuasion, cultural differences, and strategy. Moreover, one of the key challenges to leaders, as illustrated in the Ready About chapter opener, is managing change.

chapter at a glance

What Is Moral Leadership?

What Is Shared Leadership?

How Do You Lead Across Cultures?

How Do You Lead Organizational Change?

Moral Leadership

LEARNING ROADMAP Authentic Leadership / Spiritual Leadership / Servant Leadership / Ethical Leadership

All of us are aware of recent concerns about moral leadership issues. American International Group (AIG), for example, joined the growing list of firms such as Enron and Merrill Lynch, which at one time had highly questionable leadership. It appears that leaders of various government, religious, and educational entities made decisions based on short-term individual gain rather than long-term collective benefit.

As these problems have gained attention and scrutiny, there has been a stronger emphasis in research on topics including authentic leadership, servant leadership, spiritual leadership, and ethical leadership. These are the topics we will cover in our treatment of moral leadership. Essentially the moral leader is attempting to use transcendent values to stimulate action that is considered beneficial. The challenge of moral leadership starts with who you are and what you think the job of a leader should be.

Authentic Leadership

Authentic leadership essentially argues “know thyself.”1 It involves both owning one's personal experiences (values, thoughts, emotions, and beliefs) and acting in accordance with one's true self (expressing what you really think and believe, and acting accordingly). Although no one is perfectly authentic, authenticity is something to strive for. It reflects the unobstructed operation of one's true or core self. It also underlies virtually all other aspects of leadership, regardless of the particular theory or model involved.

Those high in authenticity are thought to have optimal self-esteem, or genuine, true, stable, and congruent self-esteem, as opposed to fragile self-esteem based on outside responses. Leaders who desire authentic leadership should have genuine relationships with followers and associates and display transparency, openness, and trust.2 All of these points draw on psychological well-being emphasized in positive psychology literature.3.

In positive psychology we find emphasis on self-efficacy, which is an individual's belief about the likelihood of successfully completing a specific task; optimism, the expectation of positive outcomes; hope, the tendency to look for alternative pathways to reach a desired goal; and resilience, the ability to bounce back from failure and keep forging ahead. An increase in any one of these traits is seen as increasing the others. These are important traits for a leader to demonstrate and are believed to positively influence his or her followers.

• Self-efficacy is a person's belief that he or she can perform adequately in a situation.

• Optimism is the expectation of positive outcomes.

• Hope is the tendency to look for alternative pathways to reach a desired goal.

• Resilience is the ability to bounce back from failure and keep forging ahead.

Perhaps the most important aspect of authentic leadership is the notion that being a leader begins with you and your perspective on leading others. But being authentic is just one aspect of moral leadership. A second feature is your view of the leader's task.

Spiritual Leadership

In contrast to authentic leadership, spiritual leadership can be seen as a field of inquiry within the broader setting of workplace spirituality.4 Western religious theology and practice coupled with leadership ethics and values provide much of the base for the actions of a spiritual leader. As one might expect with a view based on religion, there is considerable disagreement. One key point of contention is whether spirituality and religion are the same. To some, spirituality stems from their religion. For others, it does not. Researchers note that organized religions provide rituals, routines, and ceremonies, thereby providing a vehicle for achieving spirituality. Of course, one could be considered religious by following religious rituals but could lack spirituality, or one could reflect a strong spirituality without being religious.

OB IN POPULAR CULTURE

AUTHENTIC LEADERSHIP AND BRAVEHEART

Contemporary leadership styles are based heavily on the values of leaders. Authentic leadership exists when a leader knows her or his values and leads in accordance with them. An authentic leader will develop genuine relationships with others. Characteristics associated with this style of leadership include self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience.

Braveheart is an account loosely based on the life of William Wallace, the Guardian of Scotland, who helped liberate Scotland from England. In the movie, nobleman Robert the Bruce (Angus Macfayden), the seventeenth Earl of Scotland, finds out that Wallace (Mel Gibson) has started a rebellion. He reports to his father, who advises him to embrace the movement while he opposes it. Frustrated, the younger Bruce describes Wallace as a commoner who fights with passion and inspires others. When the father suggests a meeting with the nobles, the younger Bruce complains that they are all talk (with no action).

William Wallace brings about change because he fights not for himself, but for the rights of all Scotsmen. He exhibits self-efficacy in his belief that he can defeat the English when others have been unsuccessful. He is optimistic that he can obtain freedom for Scotland–even to the point of death. There is a hope that this freedom will allow fellow Scotsmen to live a life he dreams about. Finally, he is resilient, fighting against incredible odds, including betrayal by the Scottish nobles.

Get to Know Yourself Better At its core, authentic leadership is about knowing yourself. This requires not only understanding your strengths and weaknesses, but also knowing your core values and acting in line with them. The OB Skills Workbook provides self-assessments that paint a picture of you as a leader. Is your leadership style in accordance with your core values? What factors work against your ability to be authentic as a leader, and how do you deal with these?

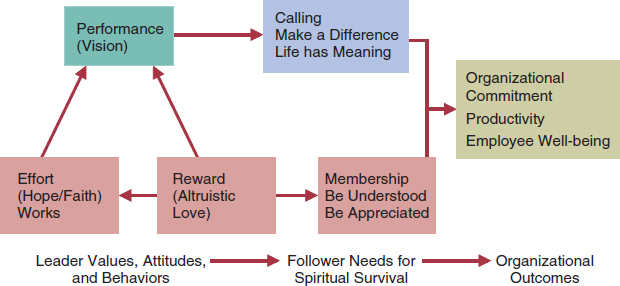

Even though spiritual leadership does not yet have a strong research base in organizational behavior, there has been some research resulting in the term Spiritual Leadership Theory, or SLT. It is a causal leadership approach for organizational transformation designed to create an intrinsically motivated, learning organization. Spiritual leadership includes values, attitudes, and behaviors required to intrinsically motivate the leader and others to have a sense of spiritual survival through calling and membership. In other words, the leader and followers experience meaning in their lives, believe they make a difference, and feel understood and appreciated. Such a sense of leader and follower survival tends to create value congruence across the strategic, empowered team and at the individual level; it ultimately encourages higher levels of organizational commitment, productivity, and employee well-being.

Figure 14.1 Causal model of spiritual leadership theory.: Source: Lewis W. Fry, Steve Vitucci, and Marie Cedillo, “Spiritual Leadership and Army Transformation: Theory, Measurement, and Establishing a Baseline,” The Leadership Quarterly 16.5 (2005), p. 838.

Figure 14.1 summarizes a causal model of spiritual leadership. It shows three core qualities of a spiritual leader: Vision—defining the destination and journey, reflecting high ideals, encouraging hope/faith; Altruistic love—trust/loyalty as well as forgiveness/acceptance/honesty, courage, and humility; Hope/Faith— endurance, perseverance, do what it takes, have stretch goals.

Servant Leadership

Servant leadership, developed by Robert K. Greenleaf, is based on the notion that the primary purpose of business should be to create a positive impact on the organization's employees as well as the community. In an essay he wrote about servant leadership in 1970, Greenleaf said: “The servant-leader is servant first…. It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead.”5

The servant leader is attuned to basic spiritual values and, in serving these, assists others including colleagues, the organization, and society. Viewed in this way servant leadership is not a unique example of leadership but rather a special kind of service. The servant leader helps others discover their inner spirit, earns and keeps the trust of their followers, exhibits effective listening skills, and places the importance of assisting others over self-interest. It is best demonstrated by those with a vision and a desire to serve others first rather than by those seeking leadership roles. Servant leadership is usually seen as a philosophical movement, with the support of the Greenleaf Center for Servant Development, an international nonprofit organization founded by Robert K. Greenleaf in 1964 and headquartered in Indiana. The Center promotes the understanding and practice of servant leadership, holds conferences, publishes books and materials, and sponsors speakers and seminars throughout the world.

While servant leadership is not rooted in OB research, its guiding philosophy is consistent with that of the other aspects of moral leadership discussed here. In this case, the power of modeling service is the basis for influencing others. You lead to serve and ask others to follow; their followership then becomes a special form of service.

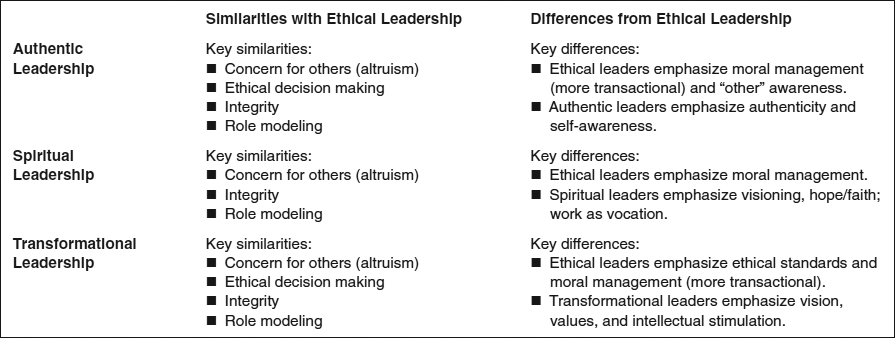

Ethical Leadership

There is no simple definition of ethical leadership. However, many believe that ethical leadership is characterized by caring, honest, principled, fair, and balanced choices by individuals who act ethically, set clear ethical standards, com-municate about ethics with followers, and reward as well as punish others based on ethical or unethical conduct.6 Figure 14.2 summarizes the similarities and differences among ethical, authentic, spiritual, and transformational leadership. A key similarity cutting across all these dimensions is role modeling. Altruism, or concern for others, and integrity are also important similarities. Leaders influence others by appealing to transcendent values. In terms of differences, authentic leaders stress authenticity and self-awareness and tend to be more transactional than do the other leaders. Ethical leaders emphasize moral concerns, while spiritual leaders stress visioning, hope, and faith, as well as work as a vocation.

Transformational leaders emphasize values, vision, and intellectual stimulation. Taken as a whole, it is clear that any of these related approaches are important and ready for systematic empirical and conceptual development. Even servant leadership would lend itself to further developments.7 Despite the lack of research, ethical leadership can and should be a driving force for improving today and tomorrow's leaders. Take a look at Ethics in OB for one example.8

Figure 14.2 Similarities and differences between ethical, spiritual, authentic, and transformational theories of leadership.: Source: Michael E. Brown and Linda K. Trevino, “Ethical Leadership: A Review and Future Directions,” The Leadership Quarterly 17.6 (December 2006), p. 598.

ETHICS IN OB

COLLEGE ATHLETES MAKE ETHICAL CHOICES

During a volleyball game, player A hits the ball over the net. The ball barely grazes off player B's fingers and lands out of bounds. However, the referee does not see player B touch the ball. Because the referee is responsible for calling rule violations, player B is not obligated to report the violation and lose the point. Do you “strongly agree,” “agree,” are “neutral” about, “disagree,” or “strongly disagree” that player B should be silent? At an increasing rate, athletes are answering “strongly agree.” In other words, winning is more important than fair play.

The above is one example of work conducted by Sharon Stoll, a University of Idaho faculty member and administrator, to see if athletes are as morally developed as the normal population. A 20-year study of some 80,000 high school, college, and professional athletes, showed that the athletes' responses on moral reasoning are less ethical than those of nonathletes. From the time male athletes enter big-time sports, their moral reasoning does not improve and it sometimes declines. The same has also recently become true of female athletes.

As part of a leadership role in this problem, Stoll has developed an educational program as a component of “Winning with Character.” The universities of Georgia and Maryland, among other athletic programs, hold weekly group discussions with athletes about ethical problem areas.

Make Ethics Personal Would you expect the ethical response differences between athletes and nonathletes? What kinds of details might you suggest be included in the weekly group discussions?

Shared Leadership

LEARNING ROADMAP Shared Leadership in Work Teams / Shared Leadership and Self-Leadership

Shared leadership is defined as a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals, or both. This influence process often involves peer or lateral influence; at other times it involves upward or downward hierarchical influence. The key distinction between shared leadership and traditional models of leadership is that the influence process involves more than just downward influence on subordinates by an appointed or elective leader. Rather, leadership is broadly distributed among a set of individuals instead of centralized in the hands of a single individual who acts in the role of a superior.9

• Shared leadership is a dynamic, interactive influence process through which individuals in teams lead one another.

Shared Leadership in Work Teams

So far our treatment of leadership has tended to treat it as vertical influence. The notion of vertical leadership is best depicted by the old Westerns of Hollywood fame. A single rider wearing a white hat and riding a white horse—the bad guys wear black hats and ride black horses—arrives in town. The townsfolk are passive and docile while they stand by and watch as the hero cleans up the town, eliminates the bad guys, and declares, “My work here is done.” You should recognize that leadership is not restricted to the vertical influence of the lone figure in a white hat but extends to other people as well. Shared and vertical leadership can be more specifically illustrated in terms of self-directing work teams.

Locations of Shared Leadership Leadership can come from outside or inside the team. Within a team, leadership can be assigned to one person, rotate across team members, or even be shared simultaneously as different needs arise across time.10 Outside the team, leaders can be traditional, formally designated, first-level supervisors, or outside vertical (top down) leaders of a self-managing team whose duties tend to be quite different from those of a traditional supervisor. Often these nontraditional leaders are called coordinators or facilitators. A key part of their job is to provide resources to their unit and serve as a liaison with other units, all without the authority trappings of traditional supervisors. Here, team members tend to carry out traditional managerial/leadership functions internal to the team along with direct performance activities.

The activities or functions vary and could involve a designated team role or even be defined more generally as a process to facilitate shared team performance. In the latter case, you are likely to see job rotation activities, along with skill-based pay, where workers are paid for the mix and depth of skills they possess as opposed to the skills of a given job assignment they might hold.

Desired Shared Conditions The key element to successful team performance is to create and maintain conditions for that performance. Although a wide variety of characteristics may be important for the success of a specific effort, five important characteristics have been identified across projects: (1) efficient, goal-directed effort; (2) adequate resources; (3) competent, motivated performance; (4) a productive, supportive climate; and (5) a commitment to continuous improvement.

Efficient, Goal-Directed Effort The key here is to coordinate the effort both inside and outside the team. Team leaders can play a crucial role and need to coordinate individual efforts with those of the team, as well as team efforts with those of the organization or major subunit. Among other things, such coordination calls for shared visions and goals.

Leaders Unlock Talent Through Diversity

Max DePree is a noted author and former CEO of the innovative furniture maker Herman Miller, Inc. He says “It is fundamental that leaders endorse the concept of persons” and that “this begins with an understanding of the diversity of people's gifts, talents, and skills.”

Adequate Resources Teams rely on their leaders to obtain enough equipment, supplies, and so on to carry out the team's goals. These are often handled by the outside facilitator and almost always involve internal and external negotiations enabling the facilitator to do his or her negotiating outside the team.

Competent, Motivated Performance Team members need the appropriate knowledge, skills, abilities, and motivation to perform collective tasks well. Leaders may be able to influence team composition so as to enhance shared efficacy and performance. We often see this demonstrated with short-term teams such as task forces.

A Productive, Supportive Climate Here, we are talking about high levels of cohesiveness, mutual trust, and cooperation among team members. Sometimes these aspects are part of a team's “interpersonal climate.” Team leaders contribute to this climate by role-modeling and supporting relationships that build the high levels of cohesion, trust, and collaboration. Team leaders can also work to enhance shared beliefs about team efficacy and collective capability.

Commitment to Continuous Improvement and Adaptation A successful team should be able to adapt to changing conditions. Again, both internal and external team leaders may play a role. The focus on continuous improvement may be through formal mechanisms. Often, however, teams recognize that a failure to strive for improvement actually results in a deterioration of performance.

Shared Leadership and Self-Leadership

These shared and vertical self-directing team activities tend to encourage self-leadership activities. Self-leadership can help both the individual and the team. All members, at one point or another, are expected to be leaders. Self-leadership represents a portfolio of self-influence strategies that positively influence individual behavior, thought processes, and related activities. Self-leadership activities are divided into three broad categories: behavior-focused, natural-reward, and constructive-thought-pattern strategies.11

Behavior-Focused Strategies Behavior-focused strategies tend to increase self-awareness, leading to the handling of behaviors involving necessary but not always pleasant tasks. These strategies include personal observation, goal setting, reward, self-correcting feedback, and practice. Self-observation involves examining your own behavior in order to increase awareness of when and why you engage in certain behaviors. Such examination identifies behaviors that should be changed, enhanced, or eliminated. Poor performance could lead to informal self-notes documenting the occurrence of unproductive behaviors. Such heightened awareness is a first step toward behavior change.

Self-Rewards It helps if you, as a team member, set high but reachable goals and provide yourself with rewards when they are reached. Self-rewards can be quite useful in moving behaviors toward goal attainment. Self-rewards can be real (e.g., a steak dinner or a new outfit) or imaginary (imagining a steak dinner or a new outfit). Also, such things as the rehearsal of desired behaviors you know will lead to self-established goals before the actual performance can prove quite useful. Rehearsals allow you to perfect skills that will be needed when the actual performance is required.

Innocent Protects Its Identity

Coco-Cola invested $44 million in Innocent, the highly regarded British maker of healthy smoothies. Innocent uses recycled bottles, gives 10 percent of profits to charity, and follows ethical marketing practices, all while selling a product consumers love. By not allowing Coke to have a majority stake for its millions, Innocent plans to keep its identity and integrity while gaining the advantages of Coke's global reach.

Constructive Thought Patterns Constructive thought patterns focus on the creation or alteration of cognitive thought processes. Self-analysis and improvement of belief systems, mental imagery of successful performance outcomes, and positive self-talk can help. Developing a mental image of the necessary actions allows you to think about what needs to be accomplished and how it will be accomplished before the stress of performance takes hold.

These activities can influence and control the team members' thoughts through the use of cognitive strategies designed to facilitate ways of thinking that can positively affect performance. Where these activities occur, they tend to serve as partial substitutes for hierarchical leadership even though they may be encouraged in a shared situation in contrast to a vertical leadership setting.

A final thought is in order before we move on. Leadership should not be restricted to the traditional style of vertical leadership, nor should the focus be primarily on shared leadership. Shared leadership appears in many forms and is often used successfully in combination with vertical leadership. As with a number of the leadership approaches discussed in this book, various contingencies operate that influence the emphasis that should be devoted to each of the leadership perspectives.

Leadership across Cultures

LEARNING ROADMAP The GLOBE Perspective / Leadership Aspects and Culture / Culturally Endorsed Leadership Matches / Universally Endorsed Aspects of Leadership

At some point in your career you will confront the challenge of cross-cultural leadership. This may come in the form of leading team members from different cultures, or it may come when you are offered your first international assignment. Or it might happen when you are asked to join in a cooperative venture with a foreign-based supplier or distributor. There are a wide variety of approaches to meeting the challenge of cross-cultural leadership. A major research project conducted by an international team of researchers provides an excellent overview of the factors you need to consider. Called Project GLOBE, it outlines the common dimensions of leadership that are important, as well as the significant differences in how effective managers lead in different cultures.

The GLOBE Perspective

Project GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Program) is an ambitious program involving over 17,000 managers from 951 organizations functioning in 62 nations throughout the world. The project, which is led by Robert House, has involved over 140 country co-investigators, as well as a coordinating team and a number of research associates.12

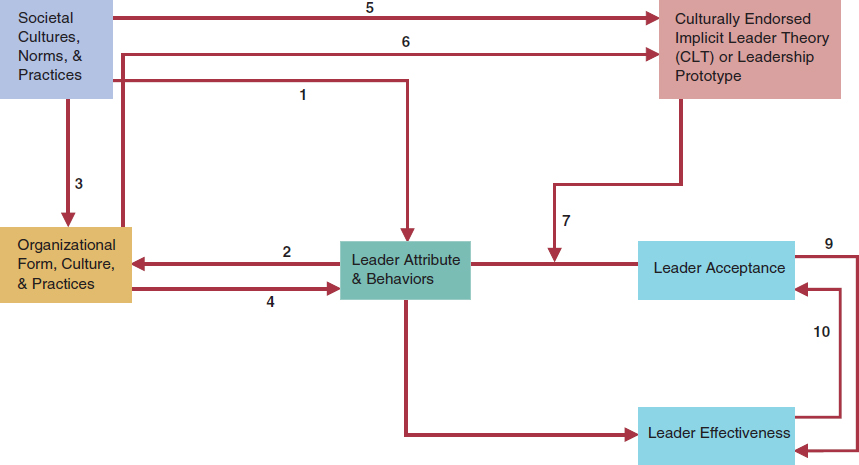

The GLOBE approach argues that leadership variables and cultural variables can be meaningfully applied at societal and organizational levels. Congruence between cultural expectations and leadership is expected to yield superior performance. The central assumption behind the model, shown in Figure 14.3, is that the attributes and entities that differentiate a specified culture predict organizational practices, leader attributes, and behaviors that are most often carried out and are most effective in that culture.

A variety of leadership assumptions are evident in the Globe theoretical model as summarized in Figure 14.3. For example, societal cultural norms, values, and practices affect leaders' attributes and behaviors, as do organizational forms, cultures, and practices. Founders and organization members are immersed in their own societal cultures as well as in the prevailing practices in their industries. Societal cultural norms, values, and practices also affect organizational culture and practices. Both societal culture and organizational culture, in turn, influence the culturally endorsed leadership prototype. And leader attributes and behaviors affect organizational forms, cultures, and practices.

Figure 14.3 also shows that acceptance of leaders by followers facilitates leadership effectiveness. Leaders who are not accepted by organization members will find it more difficult and arduous to influence these members than leaders who are accepted. Furthermore, leader effectiveness over time increases leader acceptance. Demonstrated leader effectiveness causes some members to adjust their behaviors toward the leader in positive ways. Those followers who do not accept the leader are likely to leave the organization either voluntarily or involuntarily.

Figure 14.3 A simplified version of the original GLOBE theoretical model.: Source: See Robert J. House, Paul J. Hanges, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, and Vipin Gupta (eds.), Culture, Leadership, and Organizations (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004).

Leadership Aspects and Culture

So far the GLOBE researchers have identified and studied six broad-based dimensions that can be more or less effective in different cultures. These leadership dimensions are as follows.

- Charismatic/value-based—the extent to which the leader inspires, motivates, and expects high-performance outcomes

- Team-oriented—the degree to which the leader stresses team building and implementation of a common goal among team members

- Participative—the degree to which subordinates are involved in making an implementation

- Humane-oriented—the degree to which the leader stresses support, consideration, compassion, and generosity

- Autonomous—the degree to which the leader stresses independent and individualistic leadership

- Self-protective—the degree to which the leader stresses ensuring the safety and security of the individual, self-centered, and face saving

In addition to these leadership dimensions, the GLOBE researchers also identified and studied variations in national cultures. They chose to emphasize cultural aspects known to have some relationship to effective leadership. The presumption was that leaders in different cultures would be required to adjust their approaches to best fit these cultural differences. In other words, effective leadership is based on a good fit of leadership approach and culture. The nine dimensions of societal/cultural used in the GLOBE studies are:

- Assertiveness: assertive, confrontational, and aggressive approaches in relationships versus nonconfrontational approaches

- Future orientation: future-oriented behaviors such as delaying gratification and investing in the future versus a stress on immediate gratification

- Gender egalitarianism: belief that the collective minimizes gender inequality versus asserting major differences by gender

- Uncertainty avoidance: reliance on social norms, rules, and the like to alleviate future unpredictability versus adaptation to rapid change

- Power distance: expectation that power is equally distributed versus large differences in the power of positions and individuals

- Institutional collectivism: organization/society rewards and collective resources/action versus individual rewards

- In-group collectivism: individual's expression of pride, loyalty, and similar attitudes in organizations/families versus individualism

- Performance orientation: the collective's encouragement/reward of group for performance improvement versus rewards for membership

- Humane orientation: the collective encouragement/reward of individuals for being fair, generous, and kind.

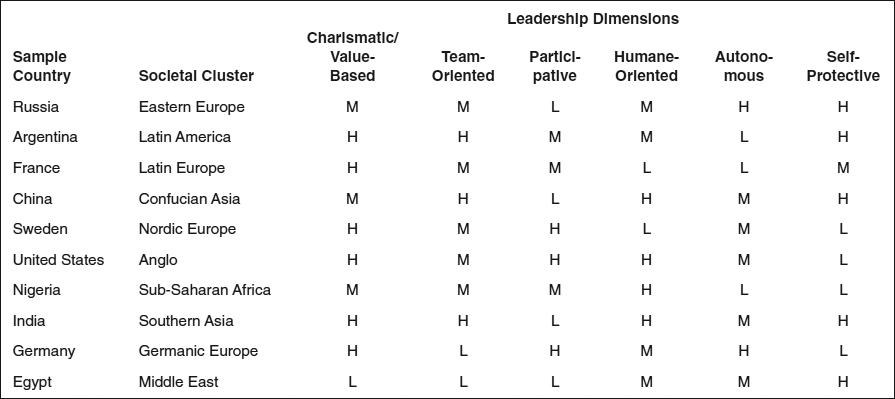

Figure 14.4 Summary of GLOBE comparisons for culturally endorsed leadership dimensions.: Source: Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, Mary Sully de Luque, and Robert J. House, “In the Eye of the Beholder: Cross Cultural Lessons in Leadership from Project GLOBE,” Academy of Management Perspectives 20.7 (2006), pp. 67-90.

Note: H = high rank; M = medium rank; L = low rank as a culturally endorsed leadership dimension.

Although each culture has its own unique pattern across these nine dimensions, nations do have enough similarities to be grouped in societal clusters. These clusters often form around geographic areas where there is a common language and an extensive pattern of interaction. For example, Argentina is a member of the Latin American societal cluster, whereas India is a member of the Southern Asian societal cluster. Figure 14.4 shows some of the major societal clusters identified in Project GLOBE and highlights a representative country for each cluster.

Culturally Endorsed Leadership Matches

So far GLOBE researchers have matched cultural and leadership dimensions for over 62 countries and have collapsed them to form 10 geographic clusters. For the six broad-based leadership dimensions, Figure 14.4 shows the degree to which a particular aspect of leadership is endorsed with an H for highly endorsed, an M for moderately endorsed, and an L for not endorsed. Where an emphasis on a specific leadership dimension is matched with an H on a cultural dimension, it is labeled a culturally endorsed leadership dimension. This aspect of leadership is characteristic of what individuals in the culture expect from an effective leader.

• A culturally endorsed leadership dimension is one that members of a culture expect from effective leaders.

Perhaps the best way to grasp this complicated perspective is to examine the patterns across the leadership dimensions by cluster in Figure 14.4. For example, in the United States the charismatic dimension is highly endorsed, whereas the protective dimension is not. For team orientation, endorsement is medium. In Russia, the self-protective dimension is culturally endorsed. Note the differences in the degree to which specific dimensions of leadership are endorsed or refuted. For instance, there is a very sharp contrast between the Anglo cluster (of which the United States is a part) and the Middle East.

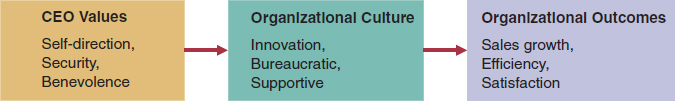

RESEARCH INSIGHT

CEO Values Make a Difference

Although there has been a lot of discussion about how the values of the CEO impact performance, comparatively few comprehensive studies have been done. Recently, Y. Berson, S. Oreg, and T. Dvir started to remedy this gap with a study of CEO values, organizational culture, and performance. They suggested that individuals are drawn to and stay with organizations that have value priorities similar to their own. That includes the CEO. Furthermore, the CEO reinforces some values over others, and this has a measurable impact on the organizational culture. The organizational culture, then, emphasizes some aspects of performance over others.

The researchers hypothesized and found the following in a study of some 22 CEOs and their firms in Israel: CEOs tend to place a high priority on self-direction or security or benevolence. This priority tends to emphasize a particular type of organizational culture. Specifically, when a CEO values self-direction, there is more cultural emphasis on innovation; when a CEO values security, there is more cultural emphasis on bureaucracy; and when a CEO values benevolence, the culture is more supportive of its members. Then they linked aspects of organizational culture with specific elements of performance (organizational outcomes). More innovation was associated with higher sales growth. A bureaucratic culture was linked to efficiency, while a supportive culture was associated with greater employee satisfaction. In sum, CEO values are linked to organizational culture, which, in turn, is associated with organizational outcomes. Schematically, it looks like this:

What Do You Think? Do you think this study would transfer to firms located in North America? Is it possible that firms with an established innovative culture select a CEO that values self-direction?

Source: Yair Berson, Shaul Oreg, and Taly Dvir, “CEO Values, Organizational Culture and Firm Outcomes.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 29 (2008), pp. 615–633.

Universally Endorsed Aspects of Leadership

Finally, GLOBE seeks to understand which attributes of leadership are universally endorsed. To date, across the sampled countries, some aspects of leadership are associated with effective leadership while others portray ineffective leadership. Leadership described in terms of integrity, charismatic-visionary, charismatic-inspirational, and team-oriented are almost universally endorsed as indications of outstanding leadership. Leadership described in terms of irritability, egocentricity, noncooperativeness, malevolence, as well as being a loner, dictatorial, and ruthless, are identified as indicators of ineffective leadership. Some aspects of leadership were seen as effective in only some national samples and involved characterizing leaders as individualistic, status conscious, risk taking, or self-sacrificing.

The important point to remember is that there are dramatically different expectations for leaders in different cultures. Leading across cultures is far from simple, as this overview of the GLOBE project suggests. Throughout the book we have stressed integrity, and the discussion of shared leadership emphasizes a team orientation. These aspects of leadership appear to be important in most cultures. In many respects the GLOBE perspective on leadership highlights the difficulty in prescribing exactly what a leader should do in our increasingly global economy. As your career progresses and you become more engaged in cross-cultural leadership, it will be important for you to go beyond a universalist view to study cultural expectations. Each culture is unique, and the pattern of cultural expectations for leaders is also unique.

Leading Organizational Change

LEARNING ROADMAP Contexts for Leadership Action / Leaders as Change Agents / Planned Change Strategies / Resistance to Change

Leaders can also change the situation facing them and their followers. Change leadership deals with the idea that an organization needs to master the challenges of change while creating a satisfying, healthy, and effective workplace for its employees. For over a decade firms have dealt with a “new economy [that] has ushered in great business opportunities—and great turmoil.”13 The terms turmoil and turbulence are particularly salient in the current economic environment. In addition to the traditional challenges, the forces of globalization provide a number of problems and opportunities, and the new economy is constantly springing surprises on even the most experienced organizational executives. Flexibility, competence, and commitment are the rules of the day. People in the new workplace must be comfortable dealing with adaptation and continuous change, along with greater productivity, willingness to learn from the successes of others, total quality, and continuous improvement.

To deal with all of these concerns and more, we will examine leaders as change agents, phases of planned change, change strategies, and resistance to change.

Contexts for Leadership Action

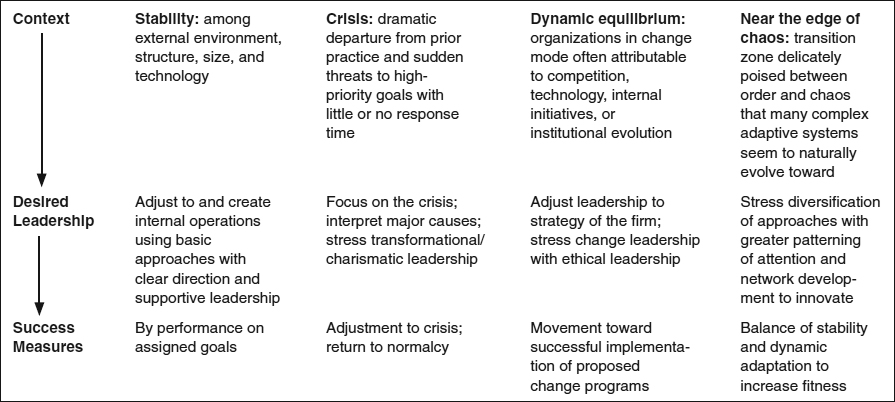

During the recent recession, it became quite clear that leaders are facing new and unique challenges. Not only have North American-based firms fully entered the information age, they have recognized the need to innovate or die. The old titans of the industrial age, the Fords, the GMs, the U.S. Steels, today look like remnants of a bygone era. Now we send tweets instead of handwritten letters; we check e-mails on our Blackberry or iPad anytime and anywhere; and we even display our photos electronically on our blogs or social networking sites, instead of in frames or photo albums. Increasingly, leaders in every level of the organization are confronting the necessity and challenges of continual innovation and the uncertainty of the age. Simply put, leaders need to be acutely aware of the setting in which they lead.14 And the leadership needed in a routine setting is not the same leadership that is needed in other contexts.15

Contextual leadership perspectives detail the conditions facing the leader and then suggest the type of leadership that is needed for success. In organizational behavior, the term context is used to describe the collection of opportunities and constraints that affect the occurrence and meaning of behavior as well as the relationships among variables.16 The different contexts may be described in terms of the stability and uncertainty facing the leader and his or her other unit.

• Context is the collection of opportunities and constraints that affect the occurrence and meaning of behavior and the relationships among variables.

For most managers there are three major sources of instability. The first is market and environmental instability. During a recession, for example, the market is extremely unstable. Second is technological instability, where what is produced and how it is produced are changing. For example, competitors may be innovating rapidly but in ways your firm cannot easily predict. Finally, there is firm instability with an emphasis on process and procedure or internal administration instability. An example is an internal production and delivery system that needs changing, but the instability is so great that the design changes cannot keep up with system demands. In other words, managers cannot clear the swamp because the alligators keep eating the workers.

Four Leadership Contexts These sources of instability can be combined to depict the overall character of the opportunities and constraints facing the leader. For simplicity consider the four contexts in Figure 14.5.17 In context 1 (Stability), stable conditions exist, and the focus is on adjusting and creating internal operations to enhance system goals. This is often the context for earlier leadership perspectives. Note that to measure success, the leader should judge progress on the basis of goals assigned to his or her unit.

In context 2 (Crisis), there are identifiable and dramatic departures from prior practice and sudden threats to high-priority goals, providing little or no response time. For many managers the current recession is such a crisis and calls for dramatic action and active leadership where charismatic and transformational leadership can be particularly important. Although the situation appears dire, leaders are aware of factors contributing to the crisis and can develop action plans to try and weather the storm. For example, in a recession, downsizing is a way to preserve the firm until the economy improves. To judge success, the leader should monitor the degree to which the unit is coping with the crisis and make sure it is on track to return to normal operations. While those in the middle can face a crisis, in cases of a dramatic downturn the firm may even bring in a new CEO.

Figure 14.5 Four situational contexts, the desired leadership, and how to measure success.: Source: Based on Osborn, Hunt, and Jauch (2002).

Finding the Leader in You

PATRICIA KARTER USES CORE VALUES AS HER GUIDE

Sweet is what one gets when digging into one of Dancing Deer Baking's Cherry Almond Ginger Chew cookies. Co-founded by Trish Karter, Dancing Deer sells over $10 million of cookies, cakes, and brownies a year. Each product is made with all-natural ingredients, packaged in recycled materials, and comes from inner-city Boston.

This story began for Karter in 1994 when she and her husband made a $20,000 Angel investment in a talented baker and set her up in a former pizza shop. Karter hadn't planned on working in the company, but growth came quickly and for the company to prosper, their baker partner, Suzanne Lombardi, needed more support and Karter jumped in. Customer demand led to product development and expansion; many positive press call outs and industry awards, such as being recognized on national TV as having the “best cake in the nation” and winning (the first of 11) Sophie awards, the food industry's equivalent of the Oscars, fueled growth further.

It isn't always easy for a leader to stay on course and in control while changing structures, adding people, and dealing with competition. But for Karter the anchor point has always been clear—let core values be the guide. Dancing Deer's employees get stock options and a package of benefits well above the industry standard; 35 percent of the sales price from the firm's Sweet Home line of cake and cookie gifts are donated to fund scholarships for homeless and at-risk mothers. When offered a chance to make a large cookie sale to Williams-Sonoma, Karter declined. Why? Because to fulfill the order would have required the use of preservatives, and that violated the company's values.

Williams-Sonoma was so impressed that it contracted to develop bakery mixes and eventually, many more products and a substantial relationship. Instead of losing an opportunity, by sticking with her values, Karter's firm gained more sales.

“There's more to life than selling cookies,” says the Dancing Deer's Web site, “but it's not a bad way to make a living.” And Karter hopes growth will soon make Dancing Deer “big enough to make an impact, to be a social economic force.” As she says on www.dancingdeer.com: “It has been an interesting journey. Our successes are due to luck, a tremendous amount of dedication and hard work, and a commitment to having fun while being true to our principles. We have had failures as well—and survived them with a sense of humor.”

What's the Lesson Here?

Do you know your core values? Do those core values guide your leadership decisions? Have you ever had your core values tested, and how did you respond?

In context 3 (Dynamic Equilibrium), organizational stability occurs only within a range of shifting priorities with programmed change efforts. This is the well-known dynamic equilibrium setting found in many analyses of corporate strategy, strategic leadership, and change leadership.

Context 4 (Near the Edge of Chaos) is a transition zone poised between order and chaos. Here, the system must rapidly adjust while maintaining sufficient stability to learn.18 While globally operating high-tech firms are classic examples of those at the edge of chaos,19 more conventional analyses of today's corporations have suggested that many firms are moving toward the edge of chaos. Why? By moving forward with a balance of exploration and exploitation, they find superior performance. Poised near the edge of chaos, firms stress innovation, responsiveness, and adaptability over routine efficiency.

Networking Leadership for the Greater Good

Managers can emphasize leadership by encouraging the formation of giving circles that bring people together for a charitable purpose.

A number of charities may arise informally or as part of a formal voluntary organization. Here are some tips for establishing the circles.

- Find out who is interested in participating in a giving circle comprised of employees who will contribute a fixed amount of money and/or time toward a charitable cause.

- Once the circle is established, provide a schedule of meeting times and locations.

- Assign an appropriate number of people, depending on the size of the group, to bring forward a cause for support.

- Educate members in a variety of activities and organizations in order to get more people involved.

- Decide on the scope of the charitable cause, whether broad, narrow, or variable.

- Keep in touch with other volunteer organizations and giving circles.

Near the edge of chaos, context 4 leaders operate in uncertainty where no one person can actually describe the challenges and opportunities facing the firm. The context is just too complex. With this level of complexity some of the traditional aspects of leadership are expected to yield very poor performance. For example, transformational leadership often fails simply because no single leader is capable of charting the necessary goals and paths to keep the system viable.20 More transactional leadership appears to provide stability but often reinforces sticking to a failed approach. The challenge is to stimulate innovation while keeping the learning environment stable. Patterning of Attention and Network Development Recent research suggests that in order to meet context challengers, leaders need to emphasize two often neglected aspects of leadership, patterning of attention and network development.21

Patterning of attention involves isolating and communicating important information from a potentially endless stream of events, actions, and outcome. The term patterning is used to stress the establishment of a norm where the leader is expected to ask questions, raise issues, and help gather information for unit members. The leader is not telling others what the goal is or how to reach it. Nor is the leader stressing an ideology or a moral position. The leader is merely stimulating discussion among others in the setting. This discussion, in turn, produces new knowledge and information as individuals develop coping strategies.

• Patterning of attention involves isolating and communicating what information is important and what is given attention from a potentially endless stream of events, actions, and outcome.

In combination, greater patterning of attention and network development increases the size, interconnectedness, and diversity of the unit to provide a variety of world views. By increasing the depth and breadth of talent in combination with increased interaction, the chances are much greater that the unit will isolate reachable goals and develop a sustaining way of accomplishing them. Too much patterning of attention and/or network development, however, can decrease the chances of effective adaptation. This becomes the case when there is too much talk and not enough action. Managers must realize that patterning of attention and network development is a delicate balancing act. Finally, network leadership can be an important aspect of influence in many contexts. An example of how it is used to establish a philanthropic entity can be found in the accompanying sidebar.22

Leaders as Change Agents

While change is the watchword for most firms, it is important to separate transformational from incremental change. Some of this change may be described as radical change, or frame-breaking change.23 This is transformational change, which results in a major overhaul of the organization or its component systems. Organizations experiencing transformational change undergo significant shifts in basic characteristics, including the overall purpose/mission, underlying values and beliefs, and supporting strategies and structures.24 In today's business environments, trans-formational changes are often initiated by a critical event, such as a new CEO, a new ownership brought about by merger or takeover, or a dramatic failure in operating results. When it occurs in the life cycle of an organization, such radical change is intense and all encompassing.25

• Transformational change radically shifts the fundamental character of an organization.

How to Increase Your Chances of Success with Transformational Change

- Develop a sense of urgency.

- Have a powerful guiding coalition.

- Have a compelling vision.

- Communicate the vision.

- Empower others to act.

- Celebrate short-term wins.

- Build on accomplishments.

- Institutionalize results.

The most common form of change is incremental change, or frame-bending change. This type of change, being part of an organization's natural evolution, is frequent and less traumatic than other types of change. Typical incremental changes include the introduction of new products, technologies, systems, and processes. Although the nature of the organization remains relatively the same, incremental change builds on the existing ways of operating to enhance or extend them in new directions. The capability of improving continuously through incremental change is an important asset in today's demanding business environment.

• Incremental change builds on the existing ways of operating to enhance or extend them in new directions.

The success of both radical and incremental change in organizations depends in part on change agents who lead and support the change processes. These are individuals and groups who take responsibility for changing the existing behavior patterns of another person or even the entire social system. Although change agents are sometimes consultants hired from outside the organization, most managers in today's dynamic times are expected to act in the capacity of change agents. Indeed, this responsibility is essential to the leadership role. Simply put, being an effective change agent means being effective at “change leadership.”

Planned and Unplanned Change Not all change in organizations is the result of a change agent's direction. Unplanned changes can occur spontaneously or randomly. They may be disruptive, such as a wildcat strike that ends in a plant closure, or beneficial, such as an interpersonal conflict that results in a new procedure designed to improve the flow of work between two departments. When the forces of unplanned change appear, the goal is to act quickly in order to minimize negative consequences and maximize possible benefits. In many cases, an unplanned change can be turned into an advantage.

• Unplanned change occurs spontaneously or randomly.

In contrast, planned change is the result of specific efforts led by a change agent. It is a direct response to someone's perception of a performance gap—a discrepancy between the desired and actual state of affairs. Performance gaps may represent problems to be solved or opportunities to be explored. Most planned changes are efforts intended to deal with performance gaps in ways that benefit an organization and its members. The processes of continuous improvement require constant vigilance to spot performance gaps and to take action to resolve them.

• Planned change is a response to someone's perception of a performance gap—a discrepancy between the desired and actual state of affairs.

• Performance gap is a discrepancy between the desired and the actual conditions.

Change Is Shorthand for Opportunity

For Fred Smith, founder and CEO of FedEx, “change is shorthand for opportunity.” He claims, “You'll get extinguished if you think you will not have to change.” Organizational change calls for a high degree of trust and outstanding communication capability.

Forces and Targets for Change The driving forces for change are ever present in and around today's dynamic work settings. They are found in the organization—environment relationship, with mergers, strategic alliances, and divestitures among the examples of organizational attempts to redefine their relationships in challenging social and political environments. They are found in the organizational life cycle, with changes in culture and structure among the examples of how organizations must adapt as they evolve from birth through growth and toward maturity. They are found in the political nature of organizations, with changes in internal control structures, including benefits and reward systems that attempt to deal with shifting political currents.

Planned change based on any of these forces can be internally directed toward a wide variety of organizational components, most of which have already been discussed in this book. As shown in Figure 14.6, these targets include organizational purpose, strategy, structure, and people, as well as objectives, culture, tasks, and technology. When considering these targets, it must be recognized that they are highly intertwined in the workplace. Changes in any one are likely to require or involve changes in others. For example, a change in the basic tasks—what people do—is inevitably accompanied by a change in technology—the way in which tasks are accomplished. Changes in tasks and technology usually require alterations in structures, including changes in the patterns of authority and communication as well as in the roles of workers. These technological and structural changes can, in turn, necessitate changes in the knowledge, skills, and behaviors of the members of the organization.26 In all cases, tendencies to accept easy-to-implement, but questionable, “quick fixes” to problems should be avoided.

Figure 14.6 Organizational targets for planned change.

Planned Change Strategies

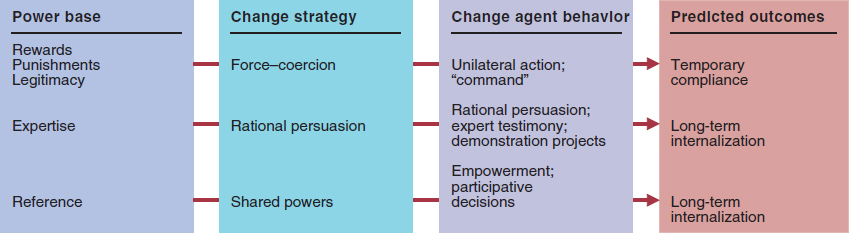

There are a variety of power change strategies utilized to mobilize power, exert influence over others, and get people to support planned change efforts. Three pure strategies—force–coercion, rational persuasion, and shared power—are described in Figure 14.7. Each of these strategies builds from the various bases of social power. Note in particular that each power source has somewhat different implications for the planned change process.27

Force–Coercion A force–coercion strategy uses authority, rewards, or punishments as primary inducements to change. Here, the leader acts unilaterally to “command” change through the formal authority of his or her position, to induce change via an offer of special rewards, or to bring about change through threats of punishment. People respond to this strategy mainly out of the fear of being punished if they do not comply with a change directive or out of the desire to gain a reward if they do. Coercion compliance is usually temporary and continues only as long as the leader is present. With reliance on legitimate authority and rewards, compliance remains as long as supervision is visible and rewards keep coming. The actions as a change agent using the force–coercion strategy might match the following profile:

• Force–coercion strategy uses authority, rewards, and punishments to create change.

You believe that people who run things are motivated by self-interest and by what the situation offers in terms of potential personal gain or loss. Since you feel that people change only in response to such motives, you try to find out where their vested interests lie and then put the pressure on. If you have formal authority, you use it. If not, you resort to whatever possible rewards and punishments you have access to and do not hesitate to threaten others with these weapons. Once you find a weakness, you exploit it and are always wise to work “politically” by building supporting alliances wherever possible.28

Figure 14.7 Power bases, change strategies, and predicted change outcomes.

Rational Persuasion Change agents using a rational persuasion strategy attempt to bring about change through the use of special knowledge, empirical support, or rational arguments. This strategy assumes that rational people will be guided by reason and self-interest in deciding whether or not to support a change. Expert power is mobilized to convince others that the change will leave them better off than before. It is sometimes referred to as an empirical-rational strategy of planned change. When successful, this strategy results in a longer-lasting, more naturalized change than does force–coercion. A change agent taking the rational persuasion approach to a change situation might behave as follows:

• Rational persuasion strategy uses facts, special knowledge, and rational argument to create change.

You believe that people are inherently rational and are guided by reason in their actions and decision making. Once a specific course of action is demonstrated to be in a person's self-interest, you assume that reason and rationality will cause the person to adopt it. Thus, you approach change with the objective of communicating—through information and facts—the essential “desirability” of change from the perspective of the person whose behavior you seek to influence. If this logic is effectively communicated, you are sure of the person who is adopting the proposed change.29

Shared Power A shared-power strategy actively involves the people who will be affected by a change in planning and making key decisions relating to this change. Sometimes called a normative-reeducative approach, this strategy tries to develop directions and support for change through involvement and empowerment. It builds essential foundations, such as personal values, group norms, and shared goals, so that support for a proposed change emerges naturally. Managers using normative-reeducative approaches draw on the power of personal reference and share power by allowing others to participate in planning and implementing the change. Given this high level of involvement, the strategy is likely to result in a longer-lasting and internalized change. A change agent who shares power and adopts a normative-reeducative approach to change is likely to fit this profile:

• Shared-power strategy uses participatory methods and emphasizes common values to create change.

You believe that people have complex motivations and behave as they do as a result of sociocultural norms and commitments to these norms. You also recognize that changes in these orientations involve changes in attitudes, values, skills, and significant relationships, not just changes in knowledge, information, or intellectual rationales for action and practice. Thus, when seeking to change others, you are sensitive to the supporting or inhibiting effects of group pressures and norms. In working with people, you try to find out their side of things and identify theirfeelings and expectations.30

Resistance to Change

In organizations, resistance to change is any attitude or behavior that indicates unwillingness to make or support a desired alteration. Leaders often view any resistance as something that must be “overcome” in order for change to be successful. This is not always the case, however. It is helpful to view resistance to change as feedback that the leader can use to facilitate gaining change objectives.31 The essence of this constructive approach to resistance is to recognize that when people resist change, they are defending something that is important to them that appears to be threatened.

• Resistance to change is any attitude or behavior that indicates unwillingness to make or support a desired change.

Why People Resist Change People have many reasons to resist change—fear of the unknown, insecurity, lack of a felt need to change, threat to vested interests, contrasting interpretations, and lack of resources, among other possibilities. A work team's members, for example, may resist the introduction of an advanced workstation of computers because they have never used the operating system and are apprehensive. They may wonder whether the new computers will eventually be used as justification for “getting rid” of certain members of their department, or they may believe that they have been doing their jobs just fine and do not need the new computers. These and other viewpoints often create resistance to even the best and most well-intended planned changes.

Resistance to the Change Itself Sometimes a leader experiences resistance to the change itself. People may reject a change because they believe it is not worth their time, effort, or attention. They may believe that the proposed change asks them to do more for less. To minimize resistance in such cases, the leader should make sure that everyone who may be affected by a change knows how it satisfies the following criteria.32

Benefit—The change should have a clear advantage for the people being asked to change; it should be perceived as “a better way.”

Compatibility—The change should be as compatible as possible with the existing values and experiences of the people being asked to change.

Complexity—The change should be no more complex than necessary; it must be as easy as possible for people to understand and use.

Triability—The change should be something that people can try on a step-by-step basis and make adjustments as things progress.

Resistance to the Change Strategy Leaders must also be prepared to deal with resistance to the change strategy. Someone who attempts to bring about change via force–coercion, for example, may create resistance among individuals who resent management of leadership by “command” or the use of threatened punishment. People may resist a rational persuasion strategy in which the data are suspect or the expertise of advocates is not clear. They may resist a sharedpower strategy that even appears manipulative and insincere.

Resistance to the Change Agent Resistance to a leader implementing the change often involves personality differences and a poor history of relationships. Leaders who are isolated and aloof from other persons in the change situation, who appear self-serving, or who have a high emotional involvement in the changes are especially prone to such problems. Research indicates that leaders who differ from other persons on such dimensions as age, education, and socioeconomic status may encounter greater resistance to change.33

How to Deal with Resistance An informed leader has many options available for dealing positively with resistance to change. Figure 14.8 summarizes insights into how and when each of these methods may be used to deal with resistance to change. Regardless of the chosen strategy, it is always best to remember that the presence of resistance typically suggests that something can be done to achieve a better fit among the change, the situation, and the people affected. A good leader deals with resistance to change by listening to feedback and acting accordingly.34

Figure 14.8 Methods for dealing with resistance to change.

The first approach in dealing with resistance to change is through education and communication. The objective is to teach people about a change before it is implemented and to help them understand the logic of the change. Education and communication seem to work best when resistance is based on inaccurate or incomplete information. A second way is the use of participation and involvement. With the goal of allowing others to help design and implement the changes, this approach asks people to contribute ideas and advice or to work on task forces or committees that may be leading the change. This is useful when the leader does not have all the information needed to successfully handle a problem situation. Here, for instance, the increased use of patterning of attention and network development by the leader may help resolve tensions.

Facilitation and support help to deal with resistance by providing help—both emotional and material—for people experiencing the hardships of change. Here a leader increases consideration by actively listening to problems and complaints. This is matched with a greater initiating structure whereby the leader provides training in the new ways and helps others to overcome performance pressures. Facilitation and support are highly recommended when people are frustrated by work constraints and difficulties encountered in the change process.

A negotiation and agreement approach offers incentives to actual or potential change resistors. Trade-offs are arranged to provide special benefits in exchange for assurances that the change will not be blocked. It is most useful when dealing with a person or group that will lose something of value as a result of the planned change.

Frustrated managers may attempt to use manipulation and co-optation in covert attempts to influence others, selectively providing information and consciously structuring events so that the desired change occurs. Although manipulation and co-optation are common when other tactics do not work, only the more astute and experienced executives find they can gain temporary reductions in resistance.

In a crisis, some leaders find that in order to overcome resistance to change they must resort to explicit or implicit coercion. Often, resistors are threatened with a variety of undesirable consequences if they do not go along with the plan. In a crisis, the temporary compliance to the change may be all that is necessary to weather the storm. Unfortunately, crises are much rarer than the use of this approach. When the crisis is past, even the temporary use of coercion means that leaders will need to embark on a new change program that stresses facilitation and support.

Finally, it is important to recognize the history, change, and culture of the firm as it undergoes planned change. Often a planned change will yield unanticipated alterations in the culture of the organization. We will spend the next chapter delving into the concept of organizational culture and the necessity to promote innovation, a unique kind of planned change.

14 study guide

Key Questions and Answers

What is moral leadership?

- Moral leadership includes authentic leadership, servant leadership, and spiritual and ethical leadership.

- Authentic leadership emphasizes owning one's personal experiences and acting in accordance with one's true or core self which underlies virtually all other aspects of leadership.

- Servant leadership is where the leader is attuned to basic spiritual values and, in serving these, serves others, including colleagues, the organization, and society.

- Spiritual leadership is a field of inquiry within the broader setting of workplace spirituality; it includes values, attitudes, and behaviors required to intrinsically motivate self and others to have a sense of spiritual survival through calling and membership.

- Ethical leadership emphasizes moral concerns.

What is shared leadership?

- Shared leadership is a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals or both.

- The influence process often involves peer or lateral influence and at other times involves upward or downward hierarchical influence within a team.

- Though broader than traditional vertical leadership, shared leadership may be used in combination with it.

- Self-leadership techniques can be used to improve the effectiveness of shared leadership.

How do you lead across cultures?

- Cross-cultural leadership emphasizes Project GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Program), which involves 62 societies, 951 organizations, and about 140 country co-investigators.

- It assumes that the attributes and entities that differentiate a specified culture predict organizational practices and leader attributes and behaviors that are most often carried out and most effective in that culture.

- It identifies a number of potentially important aspects of culture that form the basis for culturally based leader prototypes.

- It matches key aspects of leadership to the important aspects of culture to identify endorsed elements of leadership.

- It suggests both universally endorsed elements of leadership and those unique to a particular culture and group of nations.

How do you lead organizational change?

- Change leadership helps deal with the idea of an organization that masters the challenges of both radical and incremental change while still creating a satisfying, healthy, and effective employee workplace.

- Change leadership deals with leaders as change agents, phases of planned change, change strategies, and resistance to change.

- Radical or transformational change results in a major overhaul of the organization or its component systems.

- Incremental or frame-bending change as part of an organization's natural evolution is frequent and less traumatic than radical change.

- Change agents are individuals and groups who take responsibility for changing the existing behavior pattern or social system; being a change agent is an integral part of a manager's leadership role.

- Planned change strategies consist of force–coercion, rational persuasion, and shared power.

- Dealing with resistance to change involves education and communication, participation and involvement, facilitation and support, negotiation and agreement, manipulation and co-optation, and explicit or implicit agreement.

Terms to Know

Context (p. 333)

Culturally endorsed leadership dimension (p. 330)

Force-coercion strategy (p. 338)

Hope (p. 320)

Incremental change (p. 336)

Optimism (p. 320)

Patterning of attention (p. 335)

Performance gap (p. 336)

Planned change (p. 336)

Rational persuasion strategy (p. 339)

Resilience (p. 320)

Resistance to change (p. 339)

Self-efficacy (p. 320)

Shared leadership (p. 324)

Shared-power strategy (p. 339)

Transformational change (p. 335)

Unplanned change (p. 336)

Self-Test 14

Multiple Choice

- Authentic leadership__________. (a) is easily attainable (b) is the most common type of leadership (c) involves acting in accordance with one's true or core self (d) focuses on awareness of others

- Research on project GLOBE found that___________. (a) some dimensions of leadership are universally endorsed (b) there are no commonalities in leadership across cultures (c) expectations for leaders are pretty similar across cultures (d) risk-taking and self-sacrificing are the most important aspects of leadership

- The__________leader helps others discover their inner spirit, earns and keeps the trust of their followers, exhibits effective listening skills, and places the importance of assisting others over self-interest. (a) ethical (b) shared (c) servant (d) spiritual

- ___________is a causal leadership approach for organizational transformation designed to create an intrinsically motivated, learning organization. (a) Servant leadership (b) Spiritual leadership (c) Shared leadership (d) Ethical leadership

- Shared leadership_________. (a) emphasizes managerial relationships (b) is an extension of participative leadership (c) replaces vertical leadership (d) is a dynamic, interactive influence process

- Characteristics that are important for successful team performance include all but which of the following? (a) a strong vertical leader (b) efficient, goal directed effort (c) commitment to continuous improvement (d) competent, motivated performance

- Which of the following is not one of the three broad categories of self-leadership? (a) constructive-thought-pattern strategies (b) natural-reward (c) behavior-focused (d) achievement-focus

- In shared leadership teams, non-traditional leaders are often called__________. (a) task leaders (b) project managers (c) facilitators (d mentors

- Contexts are usually described in terms of_________and_________. (a) high, low (b) stability, uncertainty (c) shared, vertical (d) individualism, collectivism

- In edge of chaos contexts, transformational leadership_________. (a) is highly successful (b) is better than transactional (c) is the same as patterning of attention (d) often fails

- Two often neglected aspects of leadership are__________and_________. (a) transformational, transactional (b) shared, vertical (c) patterning of attention, network development (d) strategic, contextual

- Which type of change radically shifts the fundamental character of an organization? (a) transformational (b) incremental (c) transactional (d) hierarchical

- The most common form of change is__________. (a) transformational (b) incremental (c) transactional (d) hierarchical

- In a__________strategy, leaders use authority, rewards or punishments as primary inducements to change. (a) rational persuasion (b) shared power (c) benefit-compatibility (d) force-coercion

- _________is a change approach in which managers offer incentives to actual or potential change resistors. (a) Manipulation and co-optation (b) Explicit or implicit coercion (c) Negotiation and agreement (d) Education and communication

Short Response

- 16. Explain three ways in which shared leadership can be used in a self-directed work team.

- 17. What are the three core qualities of a spiritual leader?

- 18. What should a manager do when forces for unplanned change appear?

- 19. What internal and external forces push for change in organizations?

Applications Essay

- 20. When Jorge Maldanado became general manager of the local civic recreation center, he realized that many changes would be necessary to make the facility a true community resource. Having the benefit of a new bond issue, the center had the funds for new equipment and expanded programming. All he needed to do now was get the staff committed to new initiatives. Unfortunately, his first efforts have been met with considerable resistance to change. A typical staff comment is, “Why do all these extras? Everything is fine as it is.” How can Jorge use the strategies for dealing with resistance to change, as discussed in the chapter, to move the change process along?

Next Steps