OB Skills Workbook

SUGGESTED USES AND APPLICATIONS OF WORKBOOK MATERIALS

This is a Wiley resource—www.wiley.com/college/schermerhorn

Step 1.

Take the Learning Style Instrument at www.wiley.com/college/schermerhorn

Step 2.

The instrument will give you scores on seven learning styles:

- Visual learner—focus on visual depictions such as pictures and graphs

- Print learner—focus on seeing written words

- Auditory learner—focus on listening and hearing

- Interactive learner—focus on conversation and verbalization

- Haptic learner—focus on sense of touch or grasp

- Kinesthetic learner—focus on physical involvement

- Olfactory learner—focus on smell and taste

Step 3.

Consider your top four rankings among the learning styles. They suggest your most preferred methods of learning.

Step 4.

Read the following study tips for the learning styles. Think about how you can take best advantage of your preferred learning styles.

WHAT ARE LEARNING STYLES?

Have you ever repeated something to yourself over and over to help remember it? Or does your best friend ask you to draw a map to someplace where the two of you are planning to meet, rather than just tell her the directions? If so, then you already have an intuitive sense that people learn in different ways. Researchers in learning theory have developed various categories of learning styles. Some people, for example, learn best by reading or writing. Others learn best by using various senses—seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting, or even smelling. When you understand how you learn best, you can make use of learning strategies that will optimize the time you spend studying. To find out what your particular learning style is, go to www.wiley.com/college/boone and take the learning styles quiz you find there. The quiz will help you determine your primary learning style:

Visual Learner

Print Learner

Auditory Learner

Interactive Learner

Haptic Learner

Kinesthetic Learner

Olfactory Learner

Then, consult the information below and on the following pages for study tips for each learning style. This information will help you better understand your learning style and how to apply it to the study of business.

Study Tips for Visual Learners

If you are a Visual Learner, you prefer to work with images and diagrams. It is important that you see information.

Visual Learning

- Draw charts/diagrams during lecture.

- Examine textbook figures and graphs.

- Look at images and videos on WileyPLUS and other Web sites.

- Pay close attention to charts, drawings, and handouts your instructor uses.

- Underline; use different colors.

- Use symbols, flowcharts, graphs, different arrangements on the page, white spaces.

Visual Reinforcement

- Make flashcards by drawing tables/charts on one side and definition or description on the other side.

- Use art-based worksheets; cover labels on images in text and then rewrite the labels.

- Use colored pencils/markers and colored paper to organize information into types.

- Convert your lecture notes into “page pictures.” To do this: –Use the visual learning strategies outlined above.

- –Reconstruct images in different ways.

- –Redraw pages from memory.

- –Replace words with symbols and initials.

- –Draw diagrams where appropriate.

- –Practice turning your visuals back into words.

If visual learning is your weakness: If you are not a Visual Learner but want to improve your visual learning, try re-keying tables/charts from the textbook.

Study Tips for Print Learners

If you are a Print Learner, reading will be important but writing will be much more important.

Print Learning

- Write text lecture notes during lecture.

- Read relevant topics in textbook, especially textbook tables.

- Look at text descriptions in animations and Web sites.

- Use lists and headings.

- Use dictionaries, glossaries, and definitions.

- Read handouts, textbooks, and supplementary library readings.

- Use lecture notes.

Print Reinforcement

- Rewrite your notes from class, and copy classroom handouts in your own handwriting.

- Make your own flashcards.

- Write out essays summarizing lecture notes or text book topics.

- Develop mnemonics.

- Identify word relationships.

- Create tables with information extracted from textbook or lecture notes.

- Use text-based worksheets or crossword puzzles.

- Write out words again and again.

- Reread notes silently.

- Rewrite ideas and principles into other words.

- Turn charts, diagrams, and other illustrations into statements.

- Practice writing exam answers.

- Practice with multiple choice questions.

- Write paragraphs, especially beginnings and endings.

- Write your lists in outline form.

- Arrange your words into hierarchies and points.

If print learning is your weakness: If you are not a Print Learner but want to improve your print learning, try covering labels of figures from the textbook and writing in the labels.

Study Tips for Auditory Learners

If you are an Auditory Learner, then you prefer listening as a way to learn information. Hearing will be very important, and sound helps you focus.

Auditory Learning

- Make audio recordings during lecture. Do not skip class; hearing the lecture is essential to understanding

- Play audio files provided by instructor and textbook.

- Listen to narration of animations.

- Attend lecture and tutorials.

- Discuss topics with students and instructors.

- Explain new ideas to other people.

- Leave spaces in your lecture notes for later recall.

- Describe overheads, pictures, and visuals to somebody who was not in class.

Auditory Reinforcement

- Record yourself reading the notes and listen to the recording.

- Write out transcripts of the audio files.

- Summarize information that you have read, speaking out loud.

- Use a recorder to create self-tests.

- Compose “songs” about information.

- Play music during studying to help focus.

- Expand your notes by talking with others and with information from your textbook.

- Read summarized notes out loud.

- Explain your notes to another auditory learner.

- Talk with the instructor.

- Spend time in quiet places recalling the ideas.

- Say your answers out loud.

If auditory learning is your weakness: If you are not an Auditory Learner but want to improve your auditory learning, try writing out the scripts from pre-recorded lectures.

Study Tips for Interactive Learners

If you are an Interactive Learner, you will want to share your information. A study group will be important.

Interactive Learning

- Ask a lot of questions during lecture or TA review sessions.

- Contact other students, via e-mail or discussion forums, and ask them to explain what they learned.

Interactive Reinforcement

- “Teach” the content to a group of other students.

- Talking to an empty room may seem odd, but it will be effective for you.

- Discuss information with others, making sure that you both ask and answer questions.

- Work in small group discussions, making a verbal and written discussion of what others say.

If interactive learning is your weakness: If you are not an Interactive Learner but want to improve your interactive learning, try asking your study partner questions and then repeating them to the instructor.

Study Tips for Haptic Learners

If you are a Haptic Learner, you prefer to work with your hands. It is important to physically manipulate material.

Haptic Learning

- Take blank paper to lecture to draw charts/tables/diagrams.

- Using the textbook, run your fingers along the figures and graphs to get a “feel” for shapes and relationships.

Haptic Reinforcement

- Trace words and pictures on flash-cards.

- Perform electronic exercises that involve drag-and-drop activities.

- Alternate between speaking and writing information.

- Observe someone performing a task that you would like to learn.

- Make sure you have freedom of movement while studying.

If haptic learning is your weakness: If you are not a Haptic Learner but want to improve your haptic learning, try spending more time in class working with graphs and tables while speaking or writing down information.

Study Tips for Kinesthetic Learners

If you are a Kinesthetic Learner, it will be important that you involve your body during studying.

Kinesthetic Learning

- Ask permission to get up and move during lecture.

- Participate in role-playing activities in the classroom.

- Use all your senses.

- Go to labs; take field trips.

- Listen to real-life examples.

- Pay attention to applications.

- Use trial-and-error methods.

- Use hands-on approaches.

Kinesthetic Reinforcement

- Make flashcards; place them on the floor, and move your body around them.

- Move while you are teaching the material to others.

- Put examples in your summaries.

- Use case studies and applications to help with principles and abstract concepts.

- Talk about your notes with another kinesthetic person.

- Use pictures and photographs that illustrate an idea.

- Write practice answers.

- Role-play the exam situation.

If kinesthetic learning is your weakness: If you are not a Kinesthetic Learner but want to improve your kinesthetic learning, try moving flashcards to reconstruct graphs and tables, etc.

Study Tips for Olfactory Learners

If you are an Olfactory Learner, you will prefer to use the senses of smell and taste to reinforce learning. This is a rare learning modality.

Olfactory Learning

- During lecture, use different scented markers to identify different types of information.

Olfactory Reinforcement

- Rewrite notes with scented markers.

- If possible, go back to the computer lab to do your studying.

- Burn aromatic candles while studying.

- Try to associate the material that you're studying with a pleasant taste or smell.

If olfactory learning is your weakness: If you are not an Olfactory Learner but want to improve your olfactory learning, try burning an aromatic candle or incense while you study, or eating cookies during study sessions.

Copyright © 1998 by James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 0-7879-4425-4

Jossey-Bass is a registered trademark of Jossey-Bass Inc., a Wiley Company.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ. 07030-5774, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008. [email protected].

Printed in the United States of America.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly, call (888) 378-2537, fax to (800) 605-2665, or visit our Web site at www.josseybass.com.

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Jossey-Bass books are available to corporations, professional associations, and other organizations. For details and discount information, contact the special sales department at Jossey-Bass.

Printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

This book is printed on acid-free, recycled stock that meets or exceeds the minimum GPO and EPA requirements for recycled paper.

| CHAPTER 1 Leadership: What People Do When They're Leading |

W-14 |

| CHAPTER 2 Questions Frequently Asked About the Student LPI |

W-16 |

| CHAPTER 3 Recording Your Scores |

W-17 |

| CHAPTER 4 Interpreting Your Scores |

W-21 |

| CHAPTER 5 Summary and Action-Planning Worksheets |

W-25 |

| About the Authors | W-26 |

1 Leadership: What People Do When They're Leading

“Leadership is everyone's business.” That's the conclusion we have come to after nearly two decades of research into the behaviors and actions of people who are making a difference in their organizations, clubs, teams, classes, schools, campuses, communities, and even their families. We found that leadership is an observable, learnable set of practices. Contrary to some myths, it is not a mystical and ethereal process that cannot be understood by ordinary people. Given the opportunity for feedback and practice, those with the desire and persistence to lead—to make a difference—can substantially improve their ability to do so.

The Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI) is part of an extensive research project into the everyday actions and behaviors of people, at all levels and across a variety of settings, as they are leading. Through our research we identified five practices that are common to all leadership experiences. In collaboration with others, we extended our findings to student leaders and to school and college environments and created the student version of the LPI.1 The LPI is a tool, not a test, designed to assess your current leadership skills. It will identify your areas of strength as well as areas of leadership that need to be further developed.

The Student LPI helps you discover the extent to which you (in your role as a leader of a student group or organization) engage in the following five leadership practices:

Challenging the Process. Leaders are pioneers—people who seek out new opportunities and are willing to change the status quo. They innovate, experiment, and explore ways to improve the organization. They treat mistakes as learning experiences. Leaders also stay prepared to meet whatever challenges may confront them. Challenging the Process involves

- Searching for opportunities

- Experimenting and taking risks

As an example of Challenging the Process, one student related how innovative thinking helped him win a student class election: “I challenged the process in more than one way. First, I wanted people to understand that elections are not necessarily popularity contests, so I campaigned on the issues and did not promise things that could not possibly be done. Second, I challenged the incumbent positions. They thought they would win easily because they were incumbents, but I showed them that no one has an inherent right to a position.”

Challenging the Process for a student serving as treasurer of her sorority meant examining and abandoning some of her leadership beliefs: “I used to believe, 'If you want to do something right, do it yourself.' I found out the hard way that this is impossible to do.… One day I was ready to just give up the position because I could no longer handle all of the work. My adviser noticed that I was overwhelmed, and she turned to me and said three magic words: ‘Use your committee.’ The best piece of advice I would pass along about being an effective leader is that it is okay to experiment with letting others do the work.”

Inspiring a Shared Vision.

Leaders look toward and beyond the horizon. They envision the future with a positive and hopeful outlook. Leaders are expressive and attract other people to their organization and teams through their genuineness. They communicate and show others how their interests can be met through commitment to a common purpose. Inspiring a Shared Vision involves

- Envisioning an uplifting future

- Enlisting others in a common vision

Describing his experience as president of his high school class, one student wrote: “It was our vision to get the class united and to be able to win the spirit trophy. … I told my officers that we could do anything we set our minds on. Believe in yourself and believe in your ability to accomplish things.”

Enabling Others to Act. Leaders infuse people with energy and confidence, developing relationships based on mutual trust. They stress collaborative goals. They actively involve others in planning, giving them discretion to make their own decisions. Leaders ensure that people feel strong and capable. Enabling Others to Act involves

- Fostering collaboration

- Strengthening people

It is not necessary to be in a traditional leadership position to put these principles into practice. Here is an example from a student who led his team as a team member, not from a traditional position of power: “I helped my team members feel strong and capable by encouraging everyone to practice with the same amount of intensity that they played games with. Our practices improved throughout the year, and by the end of the year had reached the point I was striving for: complete involvement among all players, helping each other to perform at our very best during practice times.”

Modeling the Way. Leaders are clear about their personal values and beliefs. They keep people and projects on course by behaving consistently with these values and modeling how they expect others to act. Leaders also plan projects and break them down into achievable steps, creating opportunities for small wins. By focusing on key priorities, they make it easier for others to achieve goals. Modeling the Way involves

- Setting the example

- Achieving small wins

Working in a business environment taught one student the importance of Modeling the Way. She writes: “I proved I was serious because I was the first one on the job and the last one to leave. I came prepared to work and make the tools available to my crew. I worked alongside them and in no way portrayed an attitude of superiority. Instead, we were in this together.”

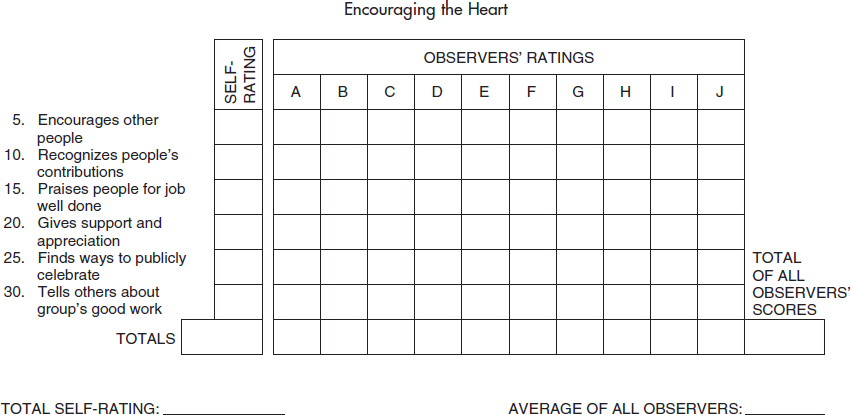

Encouraging the Heart. Leaders encourage people to persist in their efforts by linking recognition with accomplishments and visibly recognizing contributions to the common vision. They express pride in the achievements of the group or organization, letting others know that their efforts are appreciated. Leaders also find ways to celebrate milestones. They nurture a team spirit, which enables people to sustain continued efforts. Encouraging the Heart involves

- Recognizing individual contributions

- Celebrating team accomplishments

While organizing and running a day camp, one student recognized volunteers and celebrated accomplishments through her actions. She explains: “We had a pizza party with the children on the last day of the day camp. Later, the volunteers were sent thank you notes and 'valuable volunteer awards' personally signed by the day campers. The pizza party, thank you notes, and awards served to encourage the hearts of the volunteers in the hopes that they might return for next year's day camp.”

2 Questions Frequently Asked About the Student LPI

Question 1: What are the right answers?

Answer: There are no universal right answers when it comes to leadership. Research indicates that the more frequently you are perceived as engaging in the behavior and actions identified in the Student LPI, the more likely it is that you will be perceived as an effective leader. The higher your scores on the Student LPI-Observer, the more others perceive you as (1) having personal credibility, (2) being effective in running meetings, (3) successfully representing your organization or group to nonmembers, (4) generating a sense of enthusiasm and cooperation, and (5) having a high-performing team. In addition, findings show a strong and positive relationship between the extent to which people report their leaders engaging in this set of five leadership practices and how motivated, committed, and productive they feel.

Question 2: How reliable and valid is the Student LPI?

Answer: The question of reliability can be answered in two ways. First, the Student LPI has shown sound psychometric properties. The scale for each leadership practice is internally reliable, meaning that the statements within each practice are highly correlated with one another. Second, results of multivariate analyses indicate that the statements within each leadership practice are more highly correlated (or associated) with one another than they are between the five leadership practices.

In terms of validity (or “So what difference do the scores make?”), the Student LPI has good face validity and predictive validity. This means, first, that the results make sense to people. Second, scores on the Student LPI significantly differentiate high-performing leaders from their less successful counterparts. Whether measured by the leader, his or her peers, or student personnel administrators, those student leaders who engage more frequently, rather than less frequently, in the five leadership practices are more effective.

Question 3: Should my perceptions of my leadership practices be consistent with the ratings other people give me?

Answer: Research indicates that trust in the leader is essential if other people (for example, fellow members of a group, team, or organization) are going to follow that person over time. People must experience the leader as believable, credible, and trustworthy. Trust—whether in a leader or any other person—is developed through consistency in behavior. Trust is further established when words and deeds are congruent.

This does not mean, however, that you will always be perceived in exactly the same way by every person in every situation. Some people may not see you as often as others do, and therefore they may rate you differently on the same behavior. Some people simply may not know you as well as others do. Also you may appropriately behave differently in different situations, such as in a crisis versus during more stable times. Others may have different expectations of you, and still others may perceive the rating descriptions (such as “once in a while” or “fairly often”) differently.

Therefore, the key issue is not whether your self-ratings and the ratings from others are exactly the same, but whether people perceive consistency between what you say you do and what you actually do. The only way you can know the answer to this question is to solicit feedback. The Student LPI-Observer has been designed for this purpose.

Research indicates that people tend to see themselves more positively than others do. The Student LPI-Self norms are consistent with this general trend; scores on the Student LPI-Self tend to be somewhat higher than scores on the Student LPI-Observer. Student LPI scores also tend to be higher than LPI scores of experienced managers and executives in the private and public sector.

Question 4: Can I change my leadership practices?

Answer: It is certainly possible—even for experienced people—to learn new skills. You will increase your chances of changing your behavior if you receive feedback on what level you have achieved with a particular skill, observe a positive model of that skill, set some improvement goals for yourself, practice the skill, ask for updated feedback on your performance, and then set new goals. The practices that are assessed with the Student LPI fall into the category of learnable skills.

But some things can be changed only if there is a strong and genuine inner desire to make a difference. For example, enthusiasm for a cause is unlikely to be developed through education or job assignments; it must come from within.

Use the information from the Student LPI to better understand how you currently behave as a leader, both from your own perspective and from the perspective of others. Note where there are consistencies and inconsistencies. Understand which leadership behaviors and practices you feel comfortable engaging in and which you feel uncomfortable with. Determine which leadership behaviors and practices you can improve on, and take steps to improve your leadership skills and gain confidence in leading other people and groups. The following sections will help you to become more effective in leadership.

3 Recording Your Scores

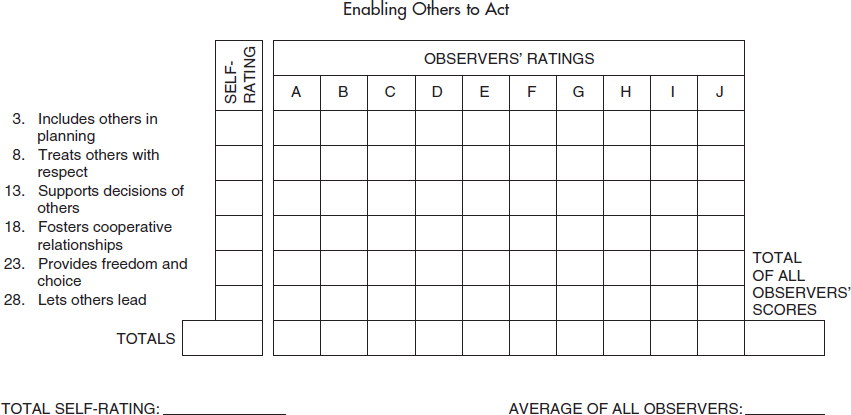

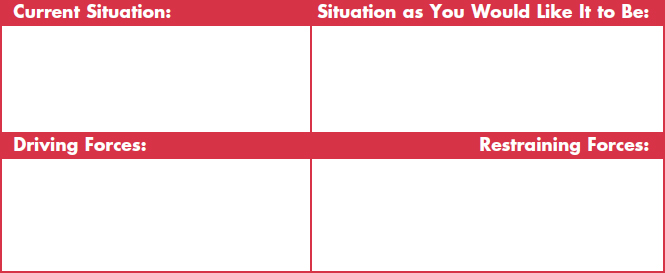

On pages W-18 through W-21 are grids for recording your Student LPI scores. The first grid (Challenging the Process) is for recording scores for items 1, 6, 11, 16, 21, and 26 from the Student LPI-Self and Student LPI-Observer. These are the items that relate to behaviors involved in Challenging the Process, such as searching for opportunities, experimenting, and taking risks. An abbreviated form of each item is printed beside the grid as a handy reference.

In the first column, which is headed “Self-Rating,” write the scores that you gave yourself. If others were asked to complete the Student LPI-Observer and if the forms were returned to you, enter their scores in the columns (A, B, C, D, E, and so on) under the heading “Observers' Ratings.” Simply transfer the numbers from page W-18 of each Student LPI-Observer to your scoring grids, using one column for each observer. For example, enter the first observer's scores in column A, the second observer's scores in column B, and so on. The grids provide space for the scores of as many as ten observers.

After all scores have been entered for Challenging the Process, total each column in the row marked “Totals.” Then add all of the totals for observers; do not include the “self” total. Write this grand total in the space marked “Total of All Observers' Scores.” To obtain the average, divide the grand total by the number of people who completed the Student LPI-Observer. Write this average in the blank provided. The sample grid shows how the grid would look with scores for self and five observers entered.

The other four grids should be completed in the same manner.

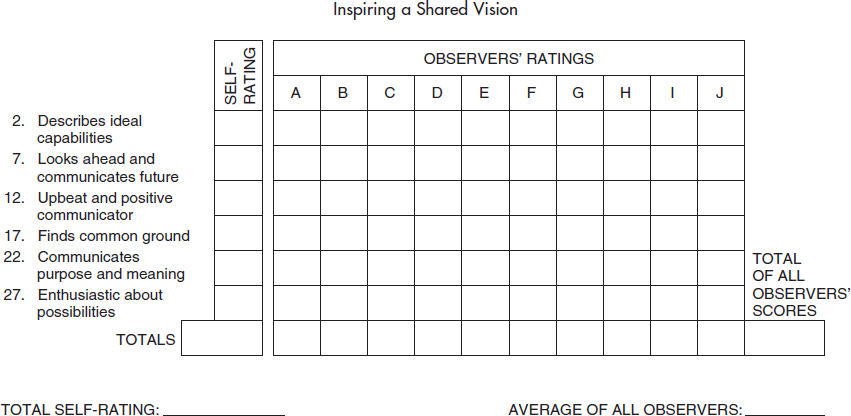

The second grid (Inspiring a Shared Vision) is for recording scores to the items that pertain to envisioning the future and enlisting the support of others. These include items 2, 7, 12, 17, 22, and 27.

The third grid (Enabling Others to Act) pertains to items 3, 8, 13, 18, 23, and 28, which involve fostering collaboration and strengthening others.

The fourth grid (Modeling the Way) pertains to items about setting an example and planning small wins. These include items 4, 9, 14, 19, 24, and 29.

The fifth grid (Encouraging the Heart) pertains to items about recognizing contributions and celebrating accomplishments. These are items 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30.

Grids for Recording Student LPI Scores

Scores should be recorded on the following grids in accordance with the instructions on page W-17. As you look at individual scores, remember the rating system that was used:

- “1” means that you rarely or seldom engage in the behavior.

- “2” means that you engage in the behavior once in a while.

- “3” means that you sometimes engage in the behavior.

- “4” means that you engage in the behavior fairly often.

- “5” means that you engage in the behavior very frequently.

After you have recorded all of your scores and calculated the totals and averages, turn to page W-21 and read the section on interpreting scores.

4 Interpreting Your Scores

This section will help you to interpret your scores by looking at them in several ways and by making notes to yourself about what you can do to become a more effective leader.

Ranking Your Ratings

Refer to the previous chapter, “Recording Your Scores.” On each grid, look at your scores in the blanks marked “Total Self-Rating.” Each of these totals represents your responses to six statements about one of the five leadership practices. Each of your totals can range from a low of 6 to a high of 30.

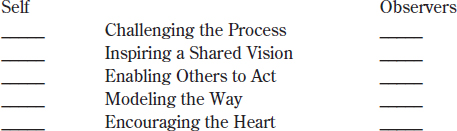

In the blanks that follow, write “1” to the left of the leadership practice with the highest total self-rating, “2” by the next-highest total self-rating, and so on. This ranking represents the leadership practices with which you feel most comfortable, second-most comfortable, and so on. The practice you identify with a “5” is the practice with which you feel least comfortable.

Again refer to the previous chapter, but this time look at your scores in the blanks marked “Average of All Observers.” The number in each blank is the average score given to you by the people you asked to complete the Student LPI-Observer. Like each of your total self-ratings, this number can range from 6 to 30.

In the blanks that follow, write “1” to the right of the leadership practice with the highest score, “2” by the next-highest score, and so on. This ranking represents the leadership practices that others feel you use most often, second-most often, and so on.

Comparing Your Self-Ratings to Observers' Ratings

To compare your Student LPI-Self and Student LPI-Observer assessments, refer to the “Chart for Graphing Your Scores” on the next page. On the chart, designate your scores on the five leadership practices (Challenging, Inspiring, Enabling, Modeling, and Encouraging) by marking each of these points with a capital “S” (for “Self'). Connect the five resulting “S scores” with a solid line and label the end of this line “Self' (see sample chart below).

If other people provided input through the Student LPI-Observer, designate the average observer scores (see the blanks labeled “Average of All Observers” on the scoring grids) by marking each of the points with a capital “O” (for “Observer”). Then connect the five resulting “O scores” with a dashed line and label the end of this line “Observer” (see sample chart). Completing this process will provide you with a graphic representation (one solid and one dashed line) illustrating the relationship between your self-perception and the observations of other people.

Look again at the “Chart for Graphing Your Scores.” The column to the far left represents the Student LPI-Self percentile rankings for more than 1,200 student leaders. A percentile ranking is determined by the percentage of people who score at or below a given number. For example, if your total self-rating for “Challenging” is at the 60th percentile line on the “Chart for Graphing Your Scores,” this means that you assessed yourself higher than 60 percent of all people who have completed the Student LPI; you would be in the top 40 percent in this leadership practice. Studies indicate that a “high” score is one at or above the 70th percentile, a “low” score is one at or below the 30th percentile, and a score that falls between those ranges is considered “moderate.”

Using these criteria, circle the “H” (for “High”), the “M” (for “Moderate”), or the “L” (for “Low”) for each leadership practice on the “Range of Scores” table below. Compared to other student leaders around the country, where do your leadership practices tend to fall? (Given a “normal distribution,” it is expected that most people's scores will fall within the moderate range.)

Range of Scores

Exploring Specific Leadership Behaviors

Looking at your scoring grids, review each of the thirty items on the Student LPI by practice. One or two of the six behaviors within each leadership practice may be higher or lower than the rest. If so, on which specific items is there variation? What do these differences suggest? On which specific items is there agreement? Please write your thoughts in the following space.

Challenging the Process

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

Inspiring a Shared Vision

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

Enabling Others to Act

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

Modeling the Way

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

Comparing Observers' Responses to One Another

Study the Student LPI-Observer scores for each of the five leadership practices. Do some respondents' scores differ significantly from others? If so, are the differences localized in the scores of one or two people? On which leadership practices do the respondents agree? On which practices do they disagree? If you try to behave basically the same with all the people who assessed you, how do you explain the difference in ratings? Please write your thoughts in the following space.

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

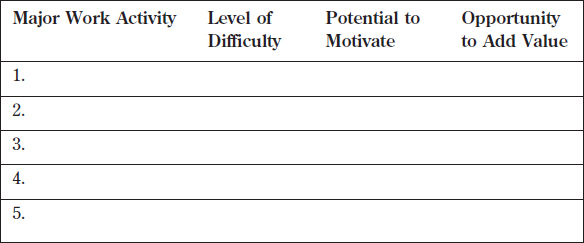

5 Summary and Action-Planning Worksheets

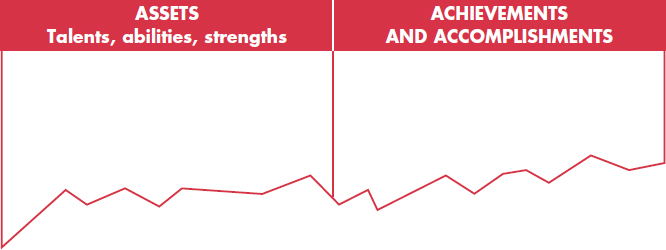

Take a few moments to summarize your Student LPI feedback by completing the following Strengths and Opportunities Summary Worksheet. Refer to the “Chart for Graphing Your Scores,” the “Range of Scores” table, and any notes you have made.

After the summary worksheet you will find some suggestions for getting started on meeting the leader-ship challenge. With these suggestions in mind, review your Student LPI feedback and decide on the actions you will take to become an even more effective leader. Then complete the Action-Planning Worksheet to spell out the steps you will take. (One Action-Planning Worksheet is included in this workbook, but you may want to develop action plans for several practices or behaviors. You can make copies of the blank form before you fill it in or just use a separate sheet of paper for each leadership practice you plan to improve.)

Strengths and Opportunities Summary Worksheet

Strengths

Which of the leadership practices and behaviors are you most comfortable with? Why? Can you do more?

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

What can you do to use a practice more frequently? What will it take to feel more comfortable?

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

The following are ten suggestions for getting started on meeting the leadership challenge.

Prescriptions for Meeting the Leadership Challenge

Challenge the Process

- Fix something

- Adopt the “great ideas” of others

Inspire a Shared Vision

- Let others know how you feel

- Recount your “personal best”

Enable Others to Act

- Always say “we”

- Make heroes of other people

Model the Way

- Lead by example

- Create opportunities for small wins

Encourage the Heart

- Write “thank you” notes

- Celebrate, and link your celebrations to your organization's values

Action-Planning Worksheet

- What would you like to be better able to do?

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________ - What specific actions will you take?

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

- What is the first action you will take? Who will be involved? When will you begin?

Action_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

People Involved_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

Target Date_____________________

- Complete this sentence: “I will know I have improved in this leadership skill when …”

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________ - When will you review your progress?_____________________

About the Authors

James M. Kouzes is chairman of TPG/Learning Systems, which makes leadership work through practical, performance-oriented learning programs. In 1993 The Wall Street Journal cited Jim as one of the twelve J most requested “nonuniversity executive-education providers” to U.S. companies. His list of past and present clients includes AT&T, Boeing, Boy Scouts of America, Charles Schwab, Ciba-Geigy, Dell Computer, First Bank System, Honeywell, Johnson & Johnson, Levi Strauss & Co., Motorola, Pacific Bell, Stanford University, Xerox Corporation, and the YMCA.

Barry Z. Posner, PhD, is dean of the Leavey School of Business, Santa Clara University, and professor of organizational behavior. He has received several outstanding teaching and leadership awards, has published more than eighty research and practitioner-oriented articles, and currently is on the editorial review boards for The Journal of Management Education, The Journal of Management Inquiry, and The Journal of Business Ethics. Barry also serves on the board of directors for Public Allies and for The Center for Excellence in Non-Profits. His clients have ranged from retailers to firms in health care, high technology, financial services, manufacturing, and community service agencies.

Kouzes and Posner are coauthors of several best-selling and award-winning leadership books. The Leadership Challenge: How to Keep Getting Extraordinary Things Done in Organizations (2nd ed., 1995), with over 800,000 copies in print, has been reprinted in fifteen languages, has been featured in three video programs, and received a Critic's Choice award from the nation's newspaper book review editors. Credibility: How Leaders Gain and Lose It, Why People Demand It (1993) was chosen by Industry Week as one of the five best management books of the year. Their latest book is Encouraging the Heart: A Leader's Guide to Rewarding and Recognizing Others (1998).

STUDENT LEADERSHIP PRACTICES INVENTORY – SELF

Your Name:_________________________________________________________

Instructions

On the next two pages are thirty statements describing various leadership behaviors. Please read each statement carefully. Then rate yourself in terms of how frequently you engage in the behavior described. This is not a test (there are no right or wrong answers).

Consider each statement in the context of the student organization (for example, club, team, chapter, group, unit, hall, program, project) with which you are most involved. The rating scale provides five choices:

- (1) If you RARELY or SELDOM do what is described in the statement, circle the number one (1).

- (2) If you do what is described ONCE IN A WHILE, circle the number two (2).

- (3) If you SOMETIMES do what is described, circle the number three (3).

- (4) If you do what is described FAIRLY OFTEN, circle the number four (4).

- (5) If you do what is described VERY FREQUENTLY or ALMOST ALWAYS, circle the number five (5).

Please respond to every statement.

In selecting the response, be realistic about the extent to which you actually engage in the behavior. Do not answer in terms of how you would like to see yourself or in terms of what you should be doing. Answer in terms of how you typically behave. The usefulness of the feedback from this inventory will depend on how honest you are with yourself about how frequently you actually engage in each of these behaviors.

For example, the first statement is “I look for opportunities that challenge my skills and abilities.” If you believe you do this “once in a while,” circle the number 2. If you believe you look for challenging opportunities “fairly often,” circle the number 4.

When you have responded to all thirty statements, please turn to the response sheet on the back page and transfer your responses as instructed. Thank you.

STUDENT LEADERSHIP PRACTICES INVENTORY – SELF

How frequently do you typically engage in the following behaviors and actions? Circle the number that applies to each statement.

After you have responded to the thirty statements on the previous two pages, please transfer your responses to the blanks below. This will make it easier to record and score your responses. Notice that the numbers of the statements are listed horizontally. Make sure that the number you assigned to each statement is transferred to the appropriate blank. Fill in a response for every item.

Further Instructions

Please write your name here:__________________________________________

Please bring this form with you to the workshop (seminar or class) or return this form to:

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

If you are interested in feedback from other people, ask them to complete the Student LPI-Observer, which provides you with perspectives on your leadership behaviors as perceived by others.

Jossey-Bass is a registered trademark of Jossey-Bass Inc., a Wiley Company.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ, 07030-5774, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008.

Printed in the United States of America.

Jossey-Bass Publishers

350 Sansome Street

San Francisco, California 94104

(888) 378-2537

Fax (800) 605-2665

Printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

This instrument is printed on acid-free, recycled stock that meets or exceeds the minimum GPO and EPA requirements for recycled paper.

ISBN: 0-7879-4426-2

STUDENT LEADERSHIP PRACTICES INVENTORY – OBSERVER

Name of Leader:____________________________________________________

Instructions

On the next two pages are thirty descriptive statements about various leadership behaviors. Please read each statement carefully. Then rate the person who asked you to complete this form in terms of how frequently he or she typically engages in the described behavior. This is not a test (there are no right or wrong answers).

Consider each statement in the context of the student organization (for example, club, team, chapter, group, unit, hall, program, project) with which that person is most involved or with which you have had the greatest opportunity to observe him or her. The rating scale provides five choices:

- (1) If this person RARELY or SELDOM does what is described in the statement, circle the number one (1).

- (2) If this person does what is described ONCE IN A WHILE, circle the number two (2).

- (3) If this person SOMETIMES does what is described, circle the number three (3).

- (4) If this person does what is described FAIRLY OFTEN, circle the number four (4).

- (5) If this person does what is described VERY FREQUENTLY or ALMOST ALWAYS, circle the number five (5).

Please respond to every statement.

In selecting the response, be realistic about the extent to which this person actually engages in the behavior. Do not answer in terms of how you would like to see this person behaving or in terms of what this person should be doing. Answer in terms of how he or she typically behaves. The usefulness of the feedback from this inventory will depend on how honest you are about how frequently you observe this person actually engaging in each of these behaviors.

For example, the first statement is, “He or she looks for opportunities that challenge his or her skills and abilities.” If you believe this person does this “once in a while,” circle the number 2. If you believe he or she looks for challenging opportunities “fairly often,” circle the number 4.

When you have responded to all thirty statements, please turn to the response sheet on the back page and transfer your responses as instructed. Thank you.

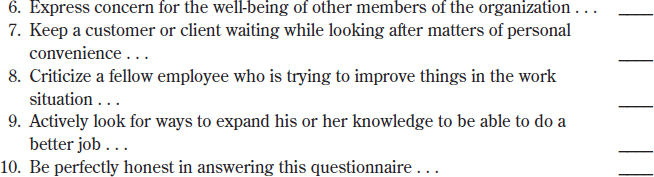

STUDENT LEADERSHIP PRACTICES INVENTORY – OBSERVER

How frequently does this person typically engage in the following behaviors and actions? Circle the number that applies to each statement:

After you have responded to the thirty statements on the previous two pages, please transfer your responses to the blanks below. This will make it easier to record and score your responses. Notice that the numbers of the statements are listed horizontally. Make sure that the number you assigned to each statement is transferred to the appropriate blank. Fill in a response for every item.

Further Instructions

The above scores are for (name of person):______________________________

Please bring this form with you to the workshop (seminar or class) or return this form to:

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

_____________________

ISBN: 0-7879-4427-0

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

Jossey-Bass Publishers

350 Sansome Street

San Francisco, California 94104

(888) 378-2537

This instrument is printed on acid-free, recycled stock that meets or exceeds the minimum GPO and EPA requirements for recycled paper.

Printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ASSESSMENT 1

Managerial Assumptions

Instructions

Read the following statements. Write “Yes” if you agree with the statement, or “No” if you disagree with it. Force yourself to take a “yes” or “no” position for every statement.

- Are good pay and a secure job enough to satisfy most workers?

- Should a manager help and coach subordinates in their work?

- Do most people like real responsibility in their jobs?

- Are most people afraid to learn new things in their jobs?

- Should managers let subordinates control the quality of their work?

- Do most people dislike work?

- Are most people creative?

- Should a manager closely supervise and direct work of subordinates?

- Do most people tend to resist change?

- Do most people work only as hard as they have to?

- Should workers be allowed to set their own job goals?

- Are most people happiest off the job?

- Do most workers really care about the organization they work for?

- Should a manager help subordinates advance and grow in their jobs?

Scoring

Count the number of “yes” responses to items 1, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12; write that number here as [X =___]. Count the number of “yes” responses to items 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 14; write that score here [Y =___].

Interpretation

This assessment gives insight into your orientation toward Douglas McGregor's Theory X (your “X” score) and Theory Y (your “Y” score) assumptions. You should review the discussion of McGregor's thinking in Chapter 1.1 and consider further the ways in which you are likely to behave toward other people at work. Think, in particular, about the types of “self-fulfilling prophecies” you are likely to create.

ASSESSMENT 2

A Twenty-First-Century Manager

Instructions

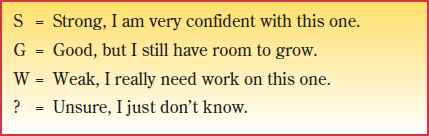

Rate yourself on the following personal characteristics. Use this scale.

- Resistance to stress: The ability to get work done even under stressful conditions.

- Tolerance for uncertainty: The ability to get work done even under ambiguous and uncertain conditions.

- Social objectivity: The ability to act free of racial, ethnic, gender, and other prejudices or biases.

- Inner work standards: The ability to personally set and work to high-performance standards.

- Stamina: The ability to sustain long work hours.

- Adaptability: The ability to be flexible and adapt to changes.

- Self-confidence: The ability to be consistently decisive and display one's personal presence.

- Self-objectivity: The ability to evaluate personal strengths and weaknesses and to understand one's motives and skills relative to a job.

- Introspection: The ability to learn from experience, awareness, and self-study.

- Entrepreneurism: The ability to address problems and take advantage of opportunities for constructive change.

Scoring

Give yourself 1 point for each S, and 1/2 point for each G. Do not give yourself points for W and ? responses. Total your points and enter the result here [PMF =___].

Interpretation

This assessment offers a self-described profile of your management foundations (PMF). Are you a perfect 10, or is your PMF score something less than that? There shouldn't be too many 10s around. Ask someone who knows you to assess you on this instrument. You may be surprised at the differences between your PMF score as self-described and your PMF score as described by someone else. Most of us, realistically speaking, must work hard to grow and develop continually in these and related management foundations. This list is a good starting point as you consider where and how to further pursue the development of your managerial skills and competencies. The items on the list are recommended by the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) as skills and personal characteristics that should be nurtured in college and university students of business administration. Their success—and yours—as twenty-first-century managers may well rest on (1) an initial awareness of the importance of these basic management foundations and (2) a willingness to strive continually to strengthen them throughout your work career.

Turbulence Tolerance Test

Instructions

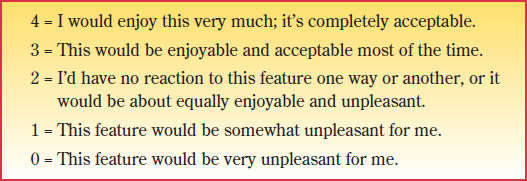

The following statements were made by a 37-year-old manager in a large, successful corporation. How would you like to have a job with these characteristics? Using the following scale, write your response to the left of each statement.

- — 1. I regularly spend 30 to 40 percent of my time in meetings.

- — 2. Eighteen months ago my job did not exist, and I have been essentially inventing it as I go along.

- — 3. The responsibilities I either assume or am assigned consistently exceed the authority I have for discharging them.

- — 4. At any given moment in my job, I have on average about a dozen phone calls to be returned.

- — 5. There seems to be very little relation between the quality of my job performance and my actual pay and fringe benefits.

- — 6. About 2 weeks a year of formal management training is needed in my job just to stay current.

- — 7. Because we have very effective equal employment opportunity (EEO) in my company and because it is thoroughly multinational, my job consistently brings me into close working contact at a professional level with people of many races, ethnic groups and nationalities, and of both sexes.

- — 8. There is no objective way to measure my effectiveness.

- — 9. I report to three different bosses for different aspects of my job, and each has an equal say in my performance appraisal.

- — 10. On average, about a third of my time is spent dealing with unexpected emergencies that force all scheduled work to be postponed.

- — 11. When I have to have a meeting of the people who report to me, it takes my secretary most of a day to find a time when we are all available, and even then I have yet to have a meeting where everyone is present for the entire meeting.

- — 12. The college degree I earned in preparation for this type of work is now obsolete, and I probably should go back for another degree.

- — 13. My job requires that I absorb 100–200 pages of technical materials per week.

- — 14. I am out of town overnight at least one night per week.

- — 15. My department is so interdependent with several other departments in the company that all distinctions about which departments are responsible for which tasks are quite arbitrary.

- — 16. In about a year I will probably get a promotion to a job in another division that has most of these same characteristics.

- — 17. During the period of my employment here, either the entire company or the division I worked in has been reorganized every year or so.

- — 18. While there are several possible promotions I can see ahead of me, I have no real career path in an objective sense.

- — 19. While there are several possible promotions I can see ahead of me, I think I have no realistic chance of getting to the top levels of the company.

- — 20. While I have many ideas about how to make things work better, I have no direct influence on either the business policies or the personnel policies that govern my division.

- — 21. My company has recently put in an “assessment center” where I and all other managers will be required to go through an extensive battery of psychological tests to assess our potential.

- — 22. My company is a defendant in an antitrust suit, and if the case comes to trial, I will probably have to testify about some decisions that were made a few years ago.

- — 23. Advanced computer and other electronic office technology is continually being introduced into my division, necessitating constant learning on my part.

- — 24. The computer terminal and screen I have in my office can be monitored in my bosses' offices without my knowledge.

Scoring

Total your responses and divide the sum by 24; enter the score here [TTT =___].

Interpretation

This instrument gives an impression of your tolerance for managing in turbulent times—something likely to characterize the world of work well into the future. In general, the higher your TTT score, the more comfortable you seem to be with turbulence and change—a positive sign. For comparison purposes, the average scores for some 500 MBA students and young managers was 1.5-1.6. The test's author suggests the TTT scores may be interpreted much like a grade point average in which 4.0 is a perfect A. On this basis, a 1.5 is below a C! How did you do?

ASSESSMENT 4

Global Readiness Index

Instructions

Use the scale to rate yourself on each of the following items to establish a baseline measurement of your readiness to participate in the global work environment.

Rating Scale

- — 1. I understand my own culture in terms of its expectations, values, and influence on communication and relationships.

- — 2. When someone presents me with a different point of view, I try to understand it rather than attack it.

- — 3. I am comfortable dealing with situations where the available information is incomplete and the outcomes unpredictable.

- — 4. I am open to new situations and am always looking for new information and learning opportunities.

- — 5. I have a good understanding of the attitudes and perceptions toward my culture as they are held by people from other cultures.

- — 6. I am always gathering information about other countries and cultures and trying to learn from them.

- — 7. I am well informed regarding the major differences in government, political systems, and economic policies around the world.

- — 8. I work hard to increase my understanding of people from other cultures.

- — 9. I am able to adjust my communication style to work effectively with people from different cultures.

- — 10. I can recognize when cultural differences are influencing working relationships and adjust my attitudes and behavior accordingly.

Interpretation

To be successful in the twenty-first-century work environment, you must be comfortable with the global economy and the cultural diversity that it holds. This requires a global mind-set that is receptive to and respectful of cultural differences, global knowledge that includes the continuing quest to know and learn more about other nations and cultures, and global work skills that allow you to work effectively across cultures.

Scoring

The goal is to score as close to a perfect “5” as possible on each of the three dimensions of global readiness. Develop your scores as follows.

ASSESSMENT 5

Personal Values

Instructions

Below are 16 items. Rate how important each one is to you on a scale of 0 (not important) to 100 (very important). Write the numbers 0-100 on the line to the left of each item.

- — 1. An enjoyable, satisfying job.

- — 2. A high-paying job.

- — 3. A good marriage.

- — 4. Meeting new people; social events.

- — 5. Involvement in community activities.

- — 6. My religion.

- — 7. Exercising, playing sports.

- — 8. Intellectual development.

- — 9. A career with challenging opportunities.

- — 10. Nice cars, clothes, home, etc.

- — 11. Spending time with family.

- — 12. Having several close friends.

- — 13. Volunteer work for not-for-profit organizations, such as the cancer society.

- — 14. Meditation, quiet time to think, pray, etc.

- — 15. A healthy, balanced diet.

- — 16. Educational reading, TV, self-improvement programs, etc.

Scoring

Transfer the numbers for each of the 16 items to the appropriate column below, then add the two numbers in each column.

Interpretation

The higher the total in any area, the higher the value you place on that particular area. The closer the numbers are in all eight areas, the more well-rounded you are. Think about the time and effort you put forth in your top three values. Is it sufficient to allow you to achieve the level of success you want in each area? If not, what can you do to change? Is there any area in which you feel you should have a higher value total? If yes, which, and what can you do to change?

ASSESSMENT 6

Intolerance for Ambiguity

Instructions

To determine your level of tolerance (intolerance) for ambiguity, respond to the following items. PLEASE RATE EVERY ITEM; DO NOT LEAVE ANY ITEM BLANK. Rate each item on the following seven-point scale:

Rating

- — 1. An expert who doesn't come up with a definite answer probably doesn't know too much.

- — 2. There is really no such thing as a problem that can't be solved.

- — 3. I would like to live in a foreign country for a while.

- — 4. People who fit their lives to a schedule probably miss the joy of living.

- — 5. A good job is one where what is to be done and how it is to be done are always clear.

- — 6. In the long run it is possible to get more done by tackling small, simple problems rather than large, complicated ones.

- — 7. It is more fun to tackle a complicated problem than it is to solve a simple one.

- — 8. Often the most interesting and stimulating people are those who don't mind being different and original.

- — 9. What we are used to is always preferable to what is unfamiliar.

- — 10. A person who leads an even, regular life in which few surprises or unexpected happenings arise really has a lot to be grateful for.

- — 11. People who insist upon a yes or no answer just don't know how complicated things really are.

- — 12. Many of our most important decisions are based on insufficient information.

- — 13. I like parties where I know most of the people more than ones where most of the people are complete strangers.

- — 14. The sooner we all acquire ideals, the better.

- — 15. Teachers or supervisors who hand out vague assignments give a chance for one to show initiative and originality.

- — 16. A good teacher is one who makes you wonder about your way of looking at things.

- — Total

Scoring

The scale was developed by S. Budner. Budner reports test-retest correlations of .85 with a variety of samples (mostly students and health care workers). Data, however, are more than 30 years old, so mean shifts may have occurred. Maximum ranges are 16-112, and score ranges were from 25 to 79, with a grand mean of approximately 49.

The test was designed to measure several different components of possible reactions to perceived threat in situations which are new, complex, or insoluble. Half of the items have been reversed.

To obtain a score, first reverse the scale score for the eight “reverse” items, 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15, and 16 (i.e., a rating of 1 = 7, 2 = 6, 3 = 5, etc.), then add up the rating scores for all 16 items.

Interpretation

Empirically, low tolerance for ambiguity (high intolerance) has been positively correlated with:

- Conventionality of religious beliefs

- High attendance at religious services

- More intense religious beliefs

- More positive views of censorship

- Higher authoritarianism

- Lower Machiavellianism

The application of this concept to management in the 1990s is clear and relatively self-evident. The world of work and many organizations are full of ambiguity and change. Individuals with a higher tolerance for ambiguity are far more likely to be able to function effectively in organizations and contexts in which there is a high turbulence, a high rate of change, and less certainty about expectations, performance standards, what needs to be done, and so on. In contrast, individuals with a lower tolerance for ambiguity are far more likely to be unable to adapt or adjust quickly in turbulence, uncertainty, and change. These individuals are likely to become rigid, angry, stressed, and frustrated when there is a high level of uncertainty and ambiguity in the environment. High levels of tolerance for ambiguity, therefore, are associated with an ability to “roll with the punches” as organizations, environmental conditions, and demands change rapidly.

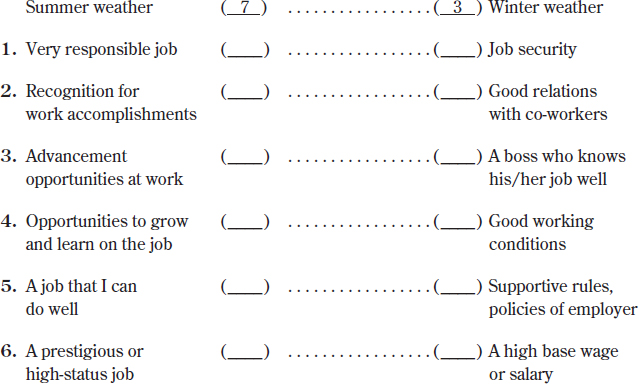

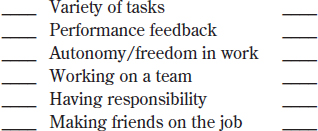

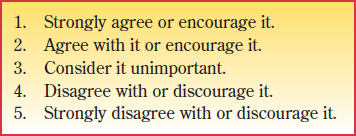

Two-Factor Profile

Instructions

On each of the following dimensions, distribute a total of 10 points between the two options. For example:

Scoring

Summarize your total scores for all items in the left-hand column and write it here: MF =___.

Summarize your total scores for all items in the right-hand column and write it here: HF =___.

Interpretation

The “MF” score indicates the relative importance that you place on motivating or satisfier factors in Herzberg's two-factor theory. This shows how important job content is to you. The “HF” score indicates the relative importance that you place on hygiene or dissatisfier factors in Herzberg's two-factor theory. This shows how important job context is to you.

ASSESSMENT 8

Are You Cosmopolitan?

Instructions

Answer the questions using a scale of 1 to 5: 1 representing “strongly disagree”; 2, “somewhat disagree”; 3, “neutral”; 4, “somewhat agree”; and 5, “strongly agree.”

- — 1. You believe it is the right of the professional to make his or her own decisions about what is to be done on the job.

- — 2. You believe a professional should stay in an individual staff role regardless of the income sacrifice.

- — 3. You have no interest in moving up to a top administrative post.

- — 4. You believe that professionals are better evaluated by professional colleagues than by management.

- — 5. Your friends tend to be members of your profession.

- — 6. You would rather be known or get credit for your work outside rather than inside the company.

- — 7. You would feel better making a contribution to society than to your organization.

- — 8. Managers have no right to place time and cost schedules on professional contributors.

Scoring and Interpretation

A “cosmopolitan” identifies with the career profession, and a “local” identifies with the employing organization. Total your scores. A score of 30–40 suggests a cosmopolitan work orientation, 10–20 a “local” orientation, and 20–30 a mixed orientation.

ASSESSMENT 9

Group Effectiveness

Instructions

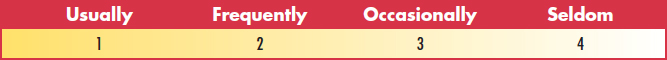

For this assessment, select a specific group you work with or have worked with; it can be a college or work group. For each of the eight statements below, select how often each statement describes the group's behavior. Place the number 1, 2, 3, or 4 on the line next to each of the 8 numbers.

- — 1. The members are loyal to one another and to the group leader.

- — 2. The members and leader have a high degree of confidence and trust in each other.

- — 3. Group values and goals express relevant values and needs of members.

- — 4. Activities of the group occur in a supportive atmosphere.

- — 5. The group is eager to help members develop to their full potential.

- — 6. The group knows the value of constructive conformity and knows when to use it and for what purpose.

- — 7. The members communicate all information relevant to the group's activity fully and frankly.

- — 8. The members feel secure in making decisions that seem appropriate to them.

Scoring

— Total. Add up the eight numbers and place an X on the continuum below that represents the score.

Effective group 8 … 16 … 24 … 32 Ineffective group

Interpretation

The lower the score, the more effective the group. What can you do to help the group become more effective? What can the group do to become more effective?

ASSESSMENT 10

Least Preferred Co-worker Scale

Instructions

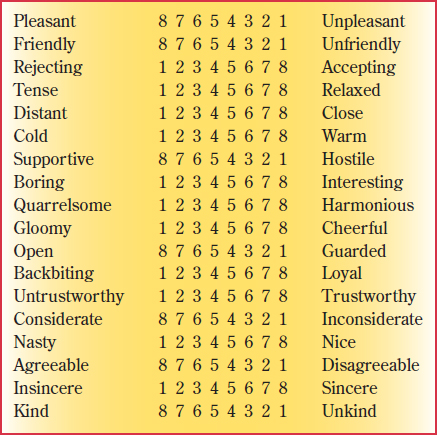

Think of all the different people with whom you have ever worked—in jobs, in social clubs, in student projects, or whatever. Next, think of the one person with whom you could work least well—that is, the person with whom you had the most difficulty getting a job done. This is the one person—a peer, boss, or subordinate—with whom you would least want to work. Describe this person by circling numbers at the appropriate points on each of the following pairs of bipolar adjectives. Work rapidly. There are no right or wrong answers.

Scoring

This is called the “least preferred co-worker scale” (LPC). Compute your LPC score by totaling all the numbers you circled; enter that score here [LPC =___].

Interpretation

The LPC scale is used by Fred Fiedler to identify a person's dominant leadership style. Fiedler believes that this style is a relatively fixed part of one's personality and is therefore difficult to change. This leads Fiedler to his contingency views, which suggest that the key to leadership success is finding (or creating) good “matches” between style and situation. If your score is 73 or above, Fiedler considers you a “relationship-motivated” leader; if your score is 64 and below, he considers you a “task-motivated” leader. If your score is between 65 and 72, Fiedler leaves it up to you to determine which leadership style is most like yours.

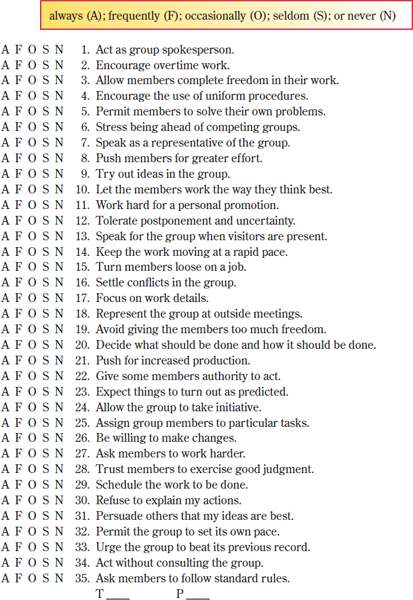

Leadership Style

Instructions

The following statements describe leadership acts. Indicate the way you would most likely act if you were leader of a workgroup, by circling whether you would most likely behave in this way:

Scoring

- Circle items 8, 12, 17, 18, 19, 30, 34, and 35.

- Write the number 1 in front of a circled item number if you responded S (seldom) or N (never) to that item.

- Write a number 1 in front of item numbers not circled if you responded A (always) or F (frequently).

- Circle the number 1's which you have written in front of items 3, 5, 8, 10, 15, 18, 19, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, and 35.

- Count the circled number 1's. This is your score for leadership concern for people. Record the score in the blank following the letter P at the end of the questionnaire.

- Count the uncircled number 1's. This is your score for leadership concern for task. Record this number in the blank following the letter T.

ASSESSMENT 12

“TT” Leadership Style

Instructions

For each of the following 10 pairs of statements, divide 5 points between the two according to your beliefs, perceptions of yourself, or according to which of the two statements characterizes you better. The 5 points may be divided between the a and b statements in any one of the following ways: 5 for a, 0 for b; 4 for a, 1 for b; 3 for a, 2 for b; 1 for a, 4 for b; 0 for a, 5 for b, but not equally (2 1/2) between the two. Weigh your choices between the two according to the one that characterizes you or your beliefs better.

-

- (a) As leader I have a primary mission of maintaining stability.

- (b) As leader I have a primary mission of change.

-

- (a) As leader I must cause events.

- (b) As leader I must facilitate events.

-

- (a) I am concerned that my followers are rewarded equitably for their work.

- (b) I am concerned about what my followers want in life.

-

- (a) My preference is to think long range: what might be.

- (b) My preference is to think short range: what is realistic.

-

- (a) As a leader I spend considerable energy in managing separate but related goals.

- (b) As a leader I spend considerable energy in arousing hopes, expectations, and aspirations among my followers.

-

- (a) Although not in a formal classroom sense, I believe that a significant part of my leadership is that of teacher.

- (b) I believe that a significant part of my leadership is that of facilitator.

-

- (a) As leader I must engage with followers at an equal level of morality.

- (b) As leader I must represent a higher morality.

-

- (a) I enjoy stimulating followers to want to do more.

- (b) I enjoy rewarding followers for a job well done.

-

- (a) Leadership should be practical.

- (b) Leadership should be inspirational.

-

- (a) What power I have to influence others comes primarily from my ability to get people to identify with me and my ideas.

- (b) What power I have to influence others comes primarily from my status and position.

Scoring

Circle your points for items 1b, 2a, 3b, 4a, 5b, 6a, 7b, 8a, 9b, 10a and add up the total points you allocated to these items; enter the score here [T =___]. Next, add up the total points given to the uncircled items 1a, 2b, 3a, 4b, 5a, 6b, 7a, 8b, 9a, 10b; enter the score here [T =___].

Interpretation

This instrument gives an impression of your tendencies toward “transformational” leadership (your T score) and “transactional” leadership (your T score). You may want to refer to the discussion of these concepts in Chapter 4. Today, a lot of attention is being given to the transformational aspects of leadership—those personal qualities that inspire a sense of vision and desire for extraordinary accomplishment in followers. The most successful leaders of the future will most likely be strong in both “T”s.

Empowering Others

Think of times when you have been in charge of a group—this could be a full-time or part-time work situation, a student workgroup, or whatever. Complete the following questionnaire by recording how you feel about each statement according to this scale.

When in charge of a group I find:

- — 1. Most of the time other people are too inexperienced to do things, so I prefer to do them myself.

- — 2. It often takes more time to explain things to others than just to do them myself.

- — 3. Mistakes made by others are costly, so I don't assign much work to them.

- — 4. Some things simply should not be delegated to others.

- — 5. I often get quicker action by doing a job myself.

- — 6. Many people are good only at very specific tasks, and thus can't be assigned additional responsibilities.

- — 7. Many people are too busy to take on additional work.

- — 8. Most people just aren't ready to handle additional responsibilities.

- — 9. In my position, I should be entitled to make my own decisions.

Scoring

Total your responses; enter the score here [___].

Interpretation

This instrument gives an impression of your willingness to delegate. Possible scores range from 9 to 45. The higher your score, the more willing you appear to be to delegate to others. Willingness to delegate is an important managerial characteristic. It is essential if you—as a manager—are to “empower” others and give them opportunities to assume responsibility and exercise self-control in their work. With the growing importance of empowerment in the new workplace, your willingness to delegate is well worth thinking about seriously.

Machiavellianism

Instructions

For each of the following statements, circle the number that most closely resembles your attitude.

Scoring and Interpretation

This assessment is designed to compute your Machiavellianism (Mach) score. Mach is a personality characteristic that taps people's power orientation. The high-Mach personality is pragmatic, maintains emotional distance from others, and believes that ends can justify means. To obtain your Mach score, add up the numbers you checked for questions 1, 3, 4, 5, 9, and 10. For the other four questions, reverse the numbers you have checked, so that 5 becomes 1; 4 is 2; and 1 is 5. Then total both sets of numbers to find your score. A random sample of adults found the national average to be 25. Students in business and management typically score higher.

The results of research using the Mach test have found: (1) men are generally more Machiavellian than women; (2) older adults tend to have lower Mach scores than younger adults; (3) there is no significant difference between high Machs and low Machs on measures of intelligence or ability; (4) Machiavellianism is not significantly related to demographic characteristics such as educational level or marital status; and (5) high Machs tend to be in professions that emphasize the control and manipulation of people—for example, managers, lawyers, psychiatrists, and behavioral scientists.

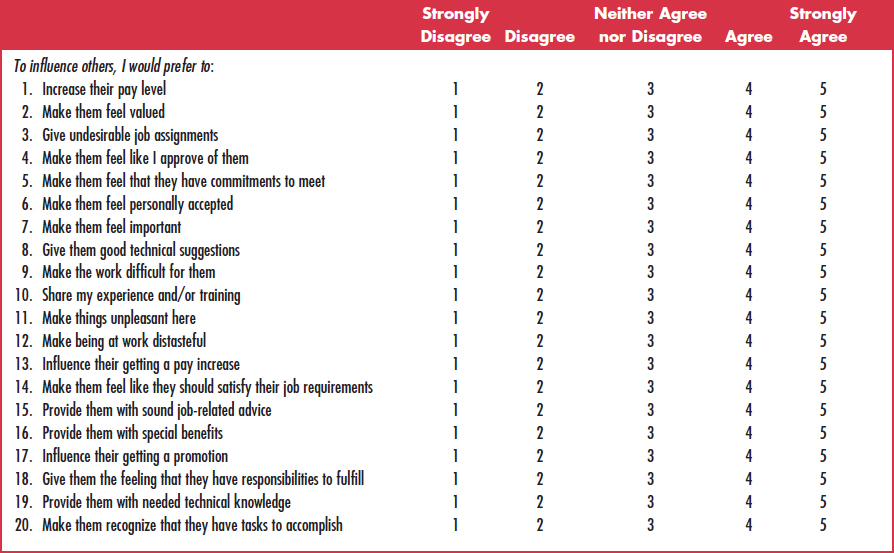

Personal Power Profile

Contributed by Marcus Maier, Chapman University

Instructions

Below is a list of statements that may be used in describing behaviors that supervisors (leaders) in work organizations can direct toward their subordinates (followers). First, carefully read each descriptive statement, thinking in terms of how you prefer to influence others. Mark the number that most closely represents how you feel. Use the following numbers for your answers.

Using the grid below, insert your scores from the 20 questions and proceed as follows: Reward power—sum your response to items 1, 13, 16, and 17 and divide by 4. Coercive power—sum your response to items 3, 9, 11, and 12 and divide by 4. Legitimate power— sum your response to questions 5, 14, 18, and 20 and divide by 4. Referent power—sum your response to questions 2, 4, 6, and 7 and divide by 4. Expert power—sum your response to questions 8, 10, 15, and 19 and divide by 4.

Interpretation

A high score (4 and greater) on any of the five dimensions of power implies that you prefer to influence others by employing that particular form of power. A low score (2 or less) implies that you prefer not to employ this particular form of power to influence others. This represents your power profile. Your overall power position is not reflected by the simple sum of the power derived from each of the five sources. Instead, some combinations of power are synergistic in nature—they are greater than the simple sum of their parts. For example, referent power tends to magnify the impact of other power sources because these other influence attempts are coming from a “respected” person. Reward power often increases the impact of referent power, because people generally tend to like those who give them things that they desire. Some power combinations tend to produce the opposite of synergistic effects, such that the total is less than the sum of the parts. Power dilution frequently accompanies the use of (or threatened use of) coercive power.

ASSESSMENT 16

Intuitive Ability

Instructions

Complete this survey as quickly as you can. Be honest with yourself. For each question, select the response that most appeals to you.

- When working on a project, do you prefer to:

- (a) Be told what the problem is but be left free to decide how to solve it?

- (b) Get very clear instructions about how to go about solving the problem before you start?

- When working on a project, do you prefer to work with colleagues who are:

- (a) Realistic?

- (b) Imaginative?

- Do you most admire people who are:

- (a) Creative?

- (b) Careful?

- Do the friends you choose tend to be:

- (a) Serious and hard working?

- (b) Exciting and often emotional?

- When you ask a colleague for advice on a problem you have, do you:

- (a) Seldom or never get upset if he or she questions your basic assumptions?

- (b) Often get upset if he or she questions your basic assumptions?

- When you start your day, do you:

- (a) Seldom make or follow a specific plan?

- (b) Usually first make a plan to follow?

- When working with numbers do you find that you:

- (a) Seldom or never make factual errors?

- (b) Often make factual errors?

- Do you find that you:

- (a) Seldom daydream during the day and really don't enjoy doing so when you do it?

- (b) Frequently daydream during the day and enjoy doing so?

- When working on a problem, do you: