Virtual Teams: Here, There, Everywhere

In an average workday, Sarah strategizes with her teammates, consults with vendors, and advises clients in several time zones. And most workdays, she's still in her pajamas.

That's one of the perks of working for a virtual team–a group whose members collaborate across time, geographic, or organizational boundaries.a Once favored mostly by creative agencies, call centers, and multinational businesses, a growing number of organizations trade the security of managing employees in house for managing them in virtual space. The hope is for increased performance, improved employee satisfaction, and ultimately, a wider selection of potential collaborators.

But when teamwork goes virtual, the potential risks as well as gains are real. Any deficiencies in employee performance or management oversight will be magnified through the lens of team-member separation. Given the extra effort needed for every communication, virtual team members may experience loneliness or perceive social isolation. And teams may suffer if all members don't have a high degree of trust and regard for each other.b

Companies wouldn't accept the risks of virtual teams if the potential payoff wasn't worth it. When teams straddle time zones, companies benefit from longer work hours, more uptime, and greater access by both fellow employees and customers. As for virtual employees, who wouldn't be happy with a flexible work schedule and a 0-minute commute?c

“My deadlines now no longer affect a voice on Skype or a person writing email–they affect my friends and colleagues.”

–Angela Sasso, on meeting her virtual teammates for the first time.d

These days, virtual employees have an impressive suite of tools that keep them tethered to their teammates. Webcams, chat, and VoIP services like Skype are de facto in most remote offices. As the quote suggests, with the right technology distant strangers become real teammates and friends. Execs who insist that it feel like virtual team members are right there (and who have deep pockets) invest in HD-quality videoconference systems.

Quick Summary

- Facilitated by the emergence of new networking technologies and ubiquitous broadband Internet, more organizations are making frequent use of virtual teams.

- Virtual teams can reduce employee travel costs, help companies approach 24/7 uptime, and give workers more flexible work schedules.

- To succeed, virtual teams require good technology, constant communication, shared priorities and deadlines, and a high degree of trust among all members.

FYI: The virtual world of workplace learning is the subject of the bestseller, The New Social Learning: A Guide to Transforming Organizations Through Social Media, by Tony Bingham, Marcia Conner, and Daniel H. Pinke

teams are hard work, but worth it

8 Teamwork and Team Performance

the key point

In order for any team–virtual or face-to-face–to work well and do great things, its members must get things right. This means paying attention to things like team building and team processes. Team performance can't be left to chance. Yes, teams can be hard work. But it's also worth the effort. The opportunities of teams and teamwork are simply too great to miss.

chapter at a glance

- What Are High-Performance Teams and How Do We Build Them?

- How Can Team Processes Be Improved?

- How Can Team Communications Be Improved?

- How Can Team Decisions Be Improved?

High-Performance Teams

LEARNING ROADMAP Characteristics of High-Performance Teams / The Team-Building Process / Team-Building Alternatives

Are you an iPod, iPhone, iPad, MacBook, or iMac user? Have you ever wondered why Apple, Inc. keeps giving us a stream of innovative and trend-setting products?

In many ways today's Apple story started years ago with its co-founder Steve Jobs, the first Macintosh computer, and a very special team. The “Mac” was Jobs's brainchild. To create it he put together a team of high-achievers who were excited and motivated by a highly challenging task. They worked all hours and at an unrelenting pace, while housed in a separate building flying the Jolly Roger to display their independence from Apple's normal bureaucracy. The Macintosh team combined youthful enthusiasm with great expertise and commitment to an exciting goal. In the process they set a new benchmark for product innovation as well as new standards for what makes for a high-performance team.1

Apple remains today a hotbed of high-performing teams that harness great talents to achieve innovation. But let's not forget that there are a lot of solid contributions made by good, old-fashioned, everyday teams in all organizations—the cross-functional, problem-solving, virtual, and self-managing teams introduced in the last chapter. We also need to remember, as scholar J. Richard Hackman points out, that many teams underperform and fail to live up to their potential. They simply, as Hackman says, “don't work.”2 The question for us is: What differentiates high-performing teams from the also-rans?

Characteristics of High-Performance Teams

Teams Gain from Great Leaders and Talented Members that Do the Right Things

- Set a clear and challenging direction

- Keep goals and expectations clear

- Communicate high standards

- Create a sense of urgency

- Make sure members have the right skills

- Model positive team member behaviors

- Create early performance “successes”

- Introduce useful information

- Help members share useful information

- Give positive feedback

Some “must-have” team leadership skills are described in the sidebar. And it's appropriate that setting a clear and challenging direction is at the top of the list.3 Again, a look back in time to the original Macintosh story sets an example. In November 1983, Wired magazine's correspondent Steven Levy was given a sneak look at what he had been told was the “machine that was supposed to change the world.” He says: “I also met the people who created that machine. They were groggy and almost giddy from three years of creation. Their eyes blazed with Visine and fire. They told me that with Macintosh, they were going to “put a dent in the Universe.” Their leader, Steven P. Jobs, told them so. They also told me how Jobs referred to this new computer: ‘Insanely Great.’”4

Whatever the purpose or tasks, the foundation for any high-performing team is a set of members who believe in team goals and are motivated to work hard to accomplish them. Indeed, an essential criterion of a high-performance team is that the members feel “collectively accountable” for moving in what Hackman calls “a compelling direction” toward a goal. Getting to this point isn't always easy. Hackman points out that members of many teams don't agree on the goal and don't share an understanding of what the team is supposed to accomplish.5

Whereas a shared sense of purpose gives general direction to a team, commitment to targeted performance results makes this purpose truly meaningful. High-performance teams turn a general sense of purpose into specific performance objectives. They set standards for taking action, measuring results, and gathering performance feedback. And they provide a clear focus for solving problems and resolving conflicts.

Members of high-performance teams have the right mix of skills, including technical, problem-solving, and interpersonal skills. A high-performance team also has strong core values that help guide team members' attitudes and behaviors in consistent directions. Such values act as an internal control system keeping team members on track without outside direction and supervisory attention.

You should recall from the last chapter the notion of collective intelligence, or the ability of a team to do well on a wide variety of tasks. This concept really i summarizes what we mean by a “high-performance” team. It is not a team that excels only once. It is a team that excels over and over again while performing different tasks over time. Researchers point out that collective intelligence is higher in teams whose processes are not dominated by one or a few members. Collective intelligence is also associated with having more female members, something researchers link to higher social sensitivity in the team process.6

• Collective intelligence is the ability of a team to perform well across a range of tasks.

The Team-Building Process

In the sports world, coaches and managers spend a lot of time at the start of each season joining new members with old ones and forming a strong team. Yet we all know that even the most experienced teams can run into problems as a season progresses. Members slack off or become disgruntled with one another; some have performance “slumps,” and others criticize them for it; some are traded gladly or unhappily to other teams.

Even world-champion teams have losing streaks. And at times even the most talented players can lose motivation, quibble among themselves, and end up contributing little to team success. When these things happen, concerned owners, managers, and players are apt to examine their problems, take corrective action to rebuild the team, and restore the teamwork needed to achieve high-performance results.7

Workgroups and teams face similar challenges. When newly formed, they must master many challenges as members learn how to work together while passing through the stages of team development. Even when mature, most work teams encounter problems of insufficient teamwork at different points in time. At the very least we can say that teams sometimes need help to perform well and that teamwork always needs to be nurtured.

This is why a process known as team-building is so important. It is a sequence of planned activities designed to gather and analyze data on the functioning of a team and to initiate changes designed to improve teamwork and increase team effectiveness.8 When done well and at the right times, team-building can be a good way to deal with teamwork problems or to help prevent them from occurring in the first place.

• Team-building is a collaborative way to gather and analyze data to improve teamwork.

Figure 8.1 Steps in the team-building process.

The action steps for team-building are highlighted in Figure 8.1. Although it is tempting to view the process as something that consultants or outside experts are hired to do, the fact is that it can and should be part of any team leader and manager's skill set.

Team-building begins when someone notices an actual or a potential problem with team effectiveness. Data are gathered to examine the problem. This can be done by questionnaire, interview, nominal group meeting, or other creative methods. The goal is to get good answers to such questions as: “How well are we doing in terms of task accomplishment?” “How satisfied are we as individuals with the group and the way it operates?” After the answers to such questions are analyzed by team members, they then work together to plan for and accomplish improvements. This team-building process is highly collaborative and participation by all members is essential.

Team-Building Alternatives

Team-building can be accomplished in a wide variety of ways. On one fall day, for example, a team of employees from American Electric Power (AEP) went to an outdoor camp. They worked on problems such as how to get six members through a spider-web maze of bungee cords strung 2 feet above the ground. When her colleagues lifted Judy Gallo into their hands to pass her over the obstacle, she was nervous. But a trainer told the team this was just like solving a problem together at the office. The spider web was just another performance constraint, like the difficult policy issues or financial limits they might face at work. After “high-fives” for making it through the web, Judy's team jumped tree stumps together, passed hula hoops while holding hands, and more. Says one outdoor team trainer, “We throw clients into situations to try and bring out the traits of a good team.”9

This was an example of the outdoor experience approach to team-building. It is increasingly popular and can be done on its own or in combination with other approaches. The outdoor experience places group members in a variety of physically challenging situations that must be mastered through teamwork. By having to work together in the face of difficult obstacles, team members are supposed to grow in self-confidence, gain more respect for each others' capabilities, and leave with a greater commitment to teamwork.

Reality Team-Building Is Catching More Attention

Some organizations are finding that borrowing ideas from “reality” TV offers novel ways to accomplish team-building and drive innovation. It sounds radical, but Best Buy sent small teams to live together for 10 weeks in Los Angeles apartments. The purpose was to demonstrate new ideas and lay the groundwork for new lines of business as well as potential independent businesses. One participant says: “Living together and knowing we only had 10 weeks sped up our team-building process”

In the formal retreat approach, team-building takes place during an off-site “retreat.” The agenda, which may cover one or more days, is designed to engage team members in the variety of assessment and planning tasks just discussed. Formal retreats are often held with the assistance of a consultant, who is either hired from the outside or made available from in-house staff. Team-building retreats are opportunities to take time away from the job to assess team accomplishments, operations, and future potential.

In a continuous improvement approach, the manager, team leader, or group members themselves take responsibility for regularly engaging in the team-building process. This method can be as simple as periodic meetings that implement the team-building steps; it can also include self-managed formal retreats. In all cases, the goal is to engage team members in a process that leaves them more capable and committed to continuous performance assessment and improved teamwork.

Improving Team Processes

LEARNING ROADMAP Entry of New Members / Task and Maintenance Leadership / Roles and Role Dynamics / Team Norms / Team Cohesiveness / Inter-Team Dynamics

As more and more jobs are turned over to teams, and as more and more traditional supervisors are asked to function as team leaders, special problems and challenges of managing team processes become magnified. Team leaders and members alike must be prepared to deal positively with such issues as introducing new members, handling disagreements on goals and responsibilities, resolving delays and disputes when making decisions, reducing personality friction, and dealing with interpersonal conflicts. These are all targets for team-building. And given the complex nature of group dynamics, team-building is, in a sense, never finished. Something is always happening that creates the need for further leadership efforts to help improve team processes.

Entry of New Members

Special difficulties are likely to occur when members first get together in a new group or team, or when new members join an existing team. Problems arise as new members try to understand what is expected of them while dealing with the anxiety and discomfort of a new social setting. New members, for example, may worry about—

- Participation—“Will I be allowed to participate?”

- Goals—“Do I share the same goals as others?”

- Control—“Will I be able to influence what takes place?”

- Relationships—“How close do people get?”

- Processes—“Are conflicts likely to be upsetting?”

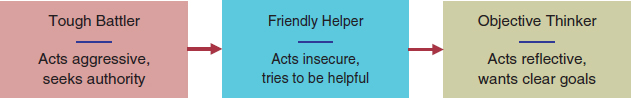

Edgar Schein points out that people may try to cope with individual entry problems in self-serving ways that may hinder team development and performance.10 He identifies three behavior profiles that are common in such situations.

Tough Battler The tough battler is frustrated by a lack of identity in the new group and may act aggressively or reject authority. This person wants answers to this question: “Who am I in this group?” The best team response may be to allow the new member to share his or her skills and interests, and then have a discussion about how these qualities can best be used to help the team.

Friendly Helper The friendly helper is insecure, suffering uncertainties of intimacy and control. This person may show extraordinary support for others, behave in a dependent way, and seek alliances in subgroups or cliques. The friendly helper needs to know whether he or she will be liked. The best team response may be to offer support and encouragement while encouraging the new member to be more confident in joining team activities and discussions.

Objective Thinker The objective thinker is anxious about how personal needs will be met in the group. This person may act in a passive, reflective, and even single-minded manner while struggling with the fit between individual goals and group directions. The best team response may be to engage in a discussion to clarify team goals and expectations, and to clarify member roles in meeting them.

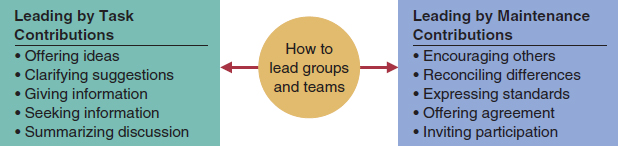

Task and Maintenance Leadership

Research in social psychology suggests that teams have both “task needs” and “maintenance needs,” and that both must be met for teams to be successful.11 Even though a team leader should be able to meet these needs at the appropriate times, each team member is responsible as well. This sharing of responsibilities for making task and maintenance contributions to move a group forward is called distributed leadership, and it is usually well evidenced in high-performance teams.

- Distributed leadership shares responsibility among members for meeting team task and maintenance needs.

Figure 8.2 Task and maintenance leadership in team dynamics.

Figure 8.2 describes task activities as things team members and leaders do that directly contribute to the performance of important group tasks. They include initiating discussion, sharing information, asking information of others, clarifying something that has been said, and summarizing the status of a deliberation.12 A team will have difficulty accomplishing its objectives when task activities are not well performed. In an effective team, by contrast, all members pitch in to contribute important task leadership as needed.

• Task activities directly contribute to the performance of important tasks.

The figure also shows that maintenance activities support the social and interpersonal relationships among team members. They help a team stay intact and healthy as an ongoing and well-functioning social system. A team member or leader can contribute maintenance leadership by encouraging the participation of others, trying to harmonize differences of opinion, praising the contributions of others, and agreeing to go along with a popular course of action. When maintenance leadership is poor, members become dissatisfied with one another, the value of their group membership diminishes, and emotional conflicts may drain energies otherwise needed for task performance. In an effective team, by contrast, maintenance activities support the relationships needed for team members to work well together over time.

• Maintenance activities support the emotional life of the team as an ongoing social system.

In addition to helping meet a group's task and maintenance needs, team members share additional responsibility for avoiding and eliminating any disruptive behaviors that harm the group process. These dysfunctional activities include bullying and being overly aggressive toward other members, showing incivility and disrespect, withdrawing and refusing to cooperate, horsing around when there is work to be done, using meetings as forums for self-confession, talking too much about irrelevant matters, and trying to compete for attention and recognition. Incivility or antisocial behavior by members can be especially disruptive of team dynamics and performance. Research shows that persons who are targets of harsh leadership, social exclusion, and harmful rumors often end up working less hard, performing less well, being late and absent more, and reducing their commitment.13

• Disruptive behaviors in teams harm the group process and limit team effectiveness.

Roles and Role Dynamics

New and old team members alike need to know what others expect of them and what they can expect from others. A role is a set of expectations associated with a job or position on a team. And, simply put, teams tend to perform better when their members have clear and realistic expectations regarding their tasks and responsibilities. When team members are unclear about their roles or face conflicting role demands, performance problems are likely. Although this is a common situation, it can be managed with good awareness of role dynamics and their causes.

• A role is a set of expectations for a team member or person in a job.

Role ambiguity occurs when a person is uncertain about his or her role or job on a team. Role ambiguities may create problems as team members find that their work efforts are wasted or unappreciated. This can even happen in mature groups if team members fail to share expectations and listen to one another's concerns.

• Role ambiguity occurs when someone is uncertain about what is expected of him or her.

Being asked to do too much or too little as a team member can also create problems. Role overload occurs when too much is expected and someone feels overwhelmed. Role underload occurs when too little is expected and the individual feels underused. Both role overload and role underload can cause stress, dissatisfaction, and performance problems.

• Role overload occurs when too much work is expected of the individual.

• Role underload occurs when too little work is expected of the individual.

Role conflict occurs when a person is unable to meet the expectations of others. The individual understands what needs to be done but for some reason cannot comply. The resulting tension is stressful and can reduce satisfaction. And, it can affect an individual's performance and relationships with other group members. People at work and in teams can experience four common forms of role conflict:

• Role conflict occurs when someone is unable to respond to role expectations that conflict with one another.

- Intrasender role conflict occurs when the same person sends conflicting expectations. Example: Team leader—“You need to get the report written right away, but now I need you to help me get the Power Points ready.”

- Intersender role conflict occurs when different people send conflicting and mutually exclusive expectations. Example: Team leader (to you)—“Your job is to criticize our decisions so that we don't make mistakes.” Team member (to you)—“You always seem so negative; can't you be more positive for a change?”

- Person–role conflict occurs when a person's values and needs come into conflict with role expectations. Example: Other team members (showing agreement with each other)—“We didn't get enough questionnaires back, so let's each fill out five more and add them to the data set.” You (to yourself)—“Mmm, I don't think this is right.”

- Inter-role conflict occurs when the expectations of two or more roles held by the same individual become incompatible, such as the conflict between work and family demands. Example: Team leader—“Don't forget the big meeting we have scheduled for Thursday evening.” You (to yourself)—“But my daughter is playing in her first little-league soccer game at that same time.”

A technique known as role negotiation is a helpful way of managing role dynamics. It's a process where team members meet to discuss, clarify, and agree upon the role expectations each holds for the other. Such a negotiation might begin, for example, with one member writing down this request of another: “If you were to do the following, it would help me to improve my performance on the team.” Her list of requests might include such things as: “respect it when I say that I can't meet some evenings because I have family obligations to fulfill”—indicating role conflict; “stop asking for so much detail when we are working hard with tight deadlines”—indicating role overload; and “try to make yourself available when I need to speak with you to clarify goals and expectations”—indicating role ambiguity.

• Role negotiation is a process for discussing and agreeing upon what team members expect of one another.

Team Norms

The role dynamics we have just discussed all relate to what team members expect of one another and of themselves. This brings up the issue of team norms—beliefs about how members are expected to behave. They can be considered as rules or standards of team conduct.14 Norms help members to guide their own behavior and predict what others will do. When someone violates a team norm, other members typically respond in ways that are aimed at enforcing it and bring behavior back into alignment with the norm. These responses may include subtle hints, direct criticisms, and even reprimands. At the extreme, someone violating team norms may be ostracized or even expelled.

• Norms are rules or standards for the behavior of group members.

Beware the Sins of Deadly Meetings

The sins of deadly meetings are easy to spot, but harder to avoid: meeting scheduled in the wrong place; meeting scheduled at a bad time; people arrive late; meeting is too long; people go off topic; discussion lacks candor; right information not available; no follow-through when meeting is over.

Types of Team Norms A key norm in any team setting is the performance norm. It conveys expectations about how hard team members should work and what the team should accomplish. In some teams the performance norm is high and strong. There is no doubt that all members are expected to work very hard and that high performance is the goal. If someone slacks off they get reminded to work hard or end up removed from the team. But in other teams the performance norm is low and weak. Members are left to work hard or not as they like, with little concern shown by the other members.

• The performance norm sets expectations for how hard members work and what the team should accomplish.

Many other norms also influence the day-to-day functioning of teams. In order for a task force or a committee to operate effectively, for example, norms regarding attendance at meetings, punctuality, preparedness, criticism, and social behavior are needed. Teams may have norms on how members deal with supervisors, colleagues, and customers, as well as norms about honesty and ethical behavior. The following examples show norms that can have positive and negative implications for teams and organizations.15

- Ethics norms—“We try to make ethical decisions, and we expect others to do the same” (positive); “Don't worry about inflating your expense account; everyone does it here” (negative).

- Organizational and personal pride norms—“It's a tradition around here for people to stand up for the company when others criticize it unfairly” (positive); “In our company, they are always trying to take advantage of us” (negative).

- High-achievement norms—“On our team, people always want to win or be the best” (positive); “No one really cares on this team whether we win or lose” (negative).

- Support and helpfulness norms—“People on this committee are good listeners and actively seek out the ideas and opinions of others” (positive); “On this committee it's dog-eat-dog and save your own skin” (negative).

- Improvement and change norms—“In our department people are always looking for better ways of doing things” (positive); “Around here, people hang on to the old ways even after they have outlived their usefulness” (negative).

SOCIAL LOAFING MAY BE CLOSER THAN YOU THINK

- Psychology study: A German researcher asked people to pull on a rope as hard as they could. First, they pulled alone. Second, they pulled as part of a group. Results showed that people pull harder when working alone than when working as part of a team. Such “social loafing” is the tendency to reduce effort when working in groups.

- Faculty office: A student wants to speak with the instructor about his team's performance on the last group project. There were four members, but two did almost all of the work. The other two largely disappeared, showing up only at the last minute to be part of the formal presentation. His point is that the team was disadvantaged because the two “free-riders” caused reduced performance capacity for his team.

- Telephone call from the boss: “John, I really need you to serve on this committee. Will you do it? Let me know tomorrow.” John thinks: I'm overloaded, but I don't want to turn down the boss. I'll accept but let the committee members know about my limits. I'll be active in discussions and try to offer viewpoints and perspectives that are helpful. However, I'll tell them front that I can't be a leader or volunteer for any extra work. Some might say this is an excuse to “slack off while still doing what the boss wants.” John views it as being honest.

You Decide Whether you call it “social loafing,” “free-riding” or just plain old “slacking off,” the issue is the same: What right do some people have to sit back in team situations and let other people do all the work? Is this ethical? Does everyone on a team have an ethical obligation to do his or her fair share of the work? And when it comes to John, does the fact that he is going to be honest with the other committee members make any difference? Isn't he still going to be a loafer, and yet earn credit with the boss for serving on the committee? Would it be more ethical for John to decline becoming a part of this committee?

How to Influence Team Norms Team leaders and members alike can do several things to help their teams develop and operate with positive norms, ones that foster high performance as well as membership satisfaction. The first thing is to always act as a positive role model. In other words, be the exemplar of the norm, always living up to the norm in everyday behavior. It is helpful to hold meetings where time is set aside for members to discuss team goals and also discuss team norms that can best contribute to their achievement. Norms are too important to be left to chance. The more directly they are discussed and confronted in the early stages of team development, the better.

It's always best to try to select members who can and will live up to the desired norms, be sure to provide training and support, and then reward and positively reinforce desired behaviors. This is a full-cycle approach to developing positive team norms—select the right people, give them support, and then offer positive reinforcement for doing things right. Finally, teams should remember the power of team-building and hold regular meetings to discuss team performance and plan how to improve it in the future.

Team Cohesiveness

The cohesiveness of a group or team is the degree to which members are attracted to and motivated to remain part of it.16 We might think of it as the “feel good” factor that causes people to value their membership on a team, positively identify with it, and strive to maintain positive relationships with other members. Feelings of cohesion can be a source of need satisfaction, often providing a source of loyalty, security, and esteem for team members. And because cohesive teams are such a source of personal satisfaction, their members tend to display fairly predictable behaviors that differentiate them from members of less cohesive teams—they are more energetic when working on team activities, less likely to be absent, less likely to quit the team, and more likely to be happy about performance success and sad about failures.

• Cohesiveness is the degree to which members are attracted to a group and motivated to remain a part of it.

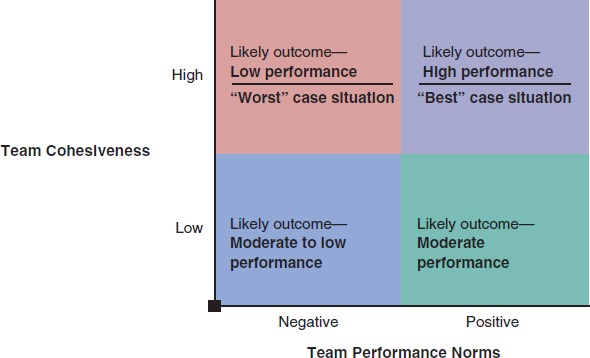

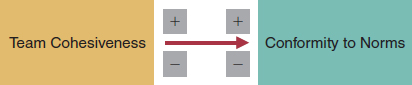

Team Cohesiveness and Conformity to Norms Even though cohesive groups are good for their members, they may or may not be good for the organization. The question is: Will the cohesive team also be a high-performance team? The answer to this question depends on the match of cohesiveness with conformity to norms.

The rule of conformity in team dynamics states that the greater the cohesiveness of a team, the greater the conformity of members to team norms. So when the performance norms are positive in a highly cohesive work group or team, the resulting conformity to the norm should have a positive effect on both team performance and member satisfaction. This is a best-case situation for team members, the team leader, and the organization. But when the performance norms are negative in a highly cohesive group, as shown in Figure 8.3, the rule of conformity creates a worst-case situation for the team leader and the organization. Although the high cohesiveness leaves the team members feeling loyal and satisfied, they are also highly motivated to conform to the negative performance norm. In between these two extremes are two mixed-case situations for teams low in cohesion. Because there is little conformity to either the positive or negative norms, team performance will most likely fall on the moderate or low side.

• The rule of conformity is the greater the cohesiveness, the greater the conformity of members to team norms.

Figure 8.3 How cohesiveness and conformity to norms influence team performance.

How to Influence Team Cohesiveness What can be done to tackle the worst-case and mixed-case scenarios just described? The answer rests with the factors influencing team cohesiveness. Cohesiveness tends to be high when teams are more homogeneous in makeup, that is when members are similar in age, attitudes, needs, and backgrounds. Cohesiveness also tends to be high in teams of small size, where members respect one another's competencies, agree on common goals, and like to work together rather than alone on team tasks. And cohesiveness tends to increase when groups are physically isolated from others and when they experience performance success or crisis.

Figure 8.4 shows how team cohesiveness can be increased or decreased by making changes in goals, membership composition, interactions, size, rewards, competition, location, and duration. When the team norms are positive but cohesiveness is low, the goal is to take actions to increase cohesion and gain more conformity to the positive norms. But when team norms are negative and cohesiveness is high, just the opposite may have to be done. If efforts to change the norms fail, it may be necessary to reduce cohesiveness and thus reduce conformity to the negative norms.

Inter-Team Dynamics

The presence of competition with other teams tends to increase cohesiveness within a team. This raises the issue of what happens between, not just within, teams. We call this inter-team dynamics. Organizations ideally operate as cooperative systems in which the various groups and teams support one another. In the real world, however, competition and inter-team problems often develop. Their consequences can be good or bad for the host organization and the teams themselves.

• Inter-team dynamics occur as groups cooperate and compete with one another.

Figure 8.4 Ways to increase and decrease team cohesiveness.

Demographic Faultlines Pose Implications for Leading Teams in Organizations

According to researchers Dora Lau and Keith Murnighan, strong “faultlines” occur in groups when demographic diversity results in the formation of two or more subgroups whose members are similar to and strongly identify with one another. Examples include teams with subgroups forming around age, gender, race, ethnic, occupational, or tenure differences. When strong faultlines are present, members are expected to identify more strongly with their subgroups than with the team as a whole. Lau and Murnighan predict that this will affect what happens with the team in terms of conflict, politics, and performance.

Using subjects from ten organizational behavior classes at a university, the researchers randomly assigned students to casework groups based on sex and ethnicity. After working on their cases, group members completed questionnaires about group processes and outcomes. Results showed, as predicted, that members in strong faultline groups evaluated those in their subgroups more favorably than did members of weak faultline groups. Members of weak faultline groups also experienced less conflict, more psychological safety, and more satisfaction than did those in strong faultline groups. More communication across faultlines had a positive effect on outcomes for weak faultline groups but not for strong faultline groups.

Do the Research See if you can verify these findings. Be a “participant observer” in your work teams. Focus on faultlines and their effects. Keep a diary, make notes, and compare your experiences with this study in mind.

Source: Dora C. Lau and J. Keith Murnighan, “Interactions within Groups and Subgroups: The Effects of Demographic Faultlines,” Academy of Management Journal 48 (2005), pp. 645–659; and “Demographic Diversity and Faultlines: The Compositional Dynamics of Organizational Groups,” Academy of Management Review 23 (1998), pp. 325–340.

On the positive side of inter-team dynamics, competition among teams can stimulate them to become more cohesive, work harder, become more focused on key tasks, develop more internal loyalty and satisfaction, or achieve a higher level of creativity in problem solving. This effect is demonstrated at virtually any intercollegiate athletic event, and it is common in work settings as well.17 On the negative side, such as when manufacturing and sales units don't get along, inter-team dynamics may drain and divert work energies. Members may spend too much time focusing on their animosities or conflicts with another team and too little time focusing on their own team's performance.18

A variety of steps can be taken to avoid negative and achieve positive effects from inter-team dynamics. Teams engaged in destructive competition, for example, can be refocused on a common enemy or a common goal. Direct negotiations can be held among the teams. Members can be engaged in intergroup team-building that encourages positive interactions and helps members of different teams learn how to work more cooperatively together. Reward systems can also be refocused to emphasize team contributions to overall organizational performance and on how much teams help out one another.

Improving Team Communications

LEARNING ROADMAP Communication Networks / Proxemics and Use of Space / Communication Technologies

Chapter 11 discusses many issues on communication and collaboration. The focus there is on such things as communication effectiveness, techniques for overcoming barriers and improving communication, and the use of collaborative communication technologies. And in teams, it is important to make sure that every member is strong and capable in basic communication and collaboration skills. In addition, however, teams must address questions like these: What communication networks are being used by the team and why? How does space affect communication among team members? Is the team making good use of the available communication technologies?

Finding the Leader in You

AMAZON'S JEFF BEZOS WINS WITH TWO-PIZZA TEAMS

Amazon.com's founder and CEO Jeff Bezos is considered one of America's top businesspersons and a technology visionary. He's also a great fan of teams. Bezos coined a simple rule when it comes to sizing the firm's product development teams: If two pizzas aren't enough to feed a team, it's too big.

The business plan for Amazon originated while Bezos was driving cross-country. He started the firm in his garage, and even when his Amazon stock grew to $500 million he was still driving a Honda and living in a small apartment in downtown Seattle. Clearly, he's a unique personality and also one with a great business mind. His goal with Amazon was to “create the world's most customer-centric company, the place where you can find and buy anything you want online.”

If you go to Amazon.com and click on the “Gold Box” at the top, you'll be tuning in to his vision. It's a place for special deals, lasting only an hour and offering everything from a power tool to a new pair of shoes. Such online innovations don't just come out of the blue. They're part and parcel of the management philosophy Bezos has instilled at the firm. The Gold Box and many of Amazon's successful innovations are products of many “two-pizza teams.” Described as “small,” “fast-moving,” and “innovation engines,” these teams typically have five to eight members and thrive on turning new ideas into business potential.

Don't expect to spot a stereotyped corporate CEO in Jeff Bezos. His standard office attire is still blue jeans and blue collared shirt. A family friend describes him and his wife as “very playful people.” Bezos views Amazon's small teams as a way of fighting bureaucracy and decentralizing, even as a company grows large and very complex. He is also a fan of what he calls fact-based decisions. He says they help to “overrule the hierarchy. The most junior person in the company can win an argument with the most senior person with fact-based decisions.”

What's the Lesson Here?

Do you need to be in control as a team leader, or are you comfortable delegating? Do you consider yourself more informal or formal in your approach to leadership? How would you feel if a person junior to you had more say in a decision than you did?

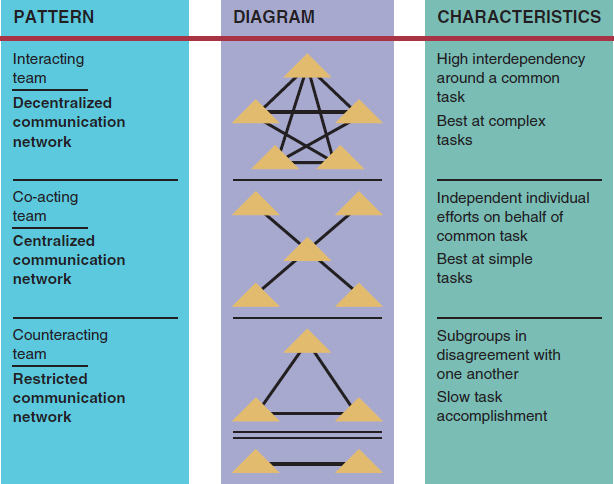

Communication Networks

Three patterns typically emerge when team members interact with one another while working on team tasks. We call them the interacting team, the co-acting team, and the counteracting team shown in Figure 8.5.

In order for a team to be effective and high-performing, the interaction pattern should fit the task at hand. Indeed, a team ideally shifts among the interaction patterns as task demands develop and change over time. One of the most common mistakes discovered during team-building is that members are not using the right interaction patterns. An example might be a student project team whose members believe every member must always be present when any work gets done on the project; in other words, no one works on his own and everything is done together.

Figure 8.5 links interaction patterns with team communication networks.19 When task demands require intense interaction, this is best done with a decentralized communication network. Also called the star network or all-channel network, it operates with everyone communicating and sharing information with everyone else. Information flows back and forth constantly, with no one person serving as the center point.20 Decentralized communication networks work well when team tasks are complex and nonroutine, perhaps tasks that involve uncertainty and require creativity. Member satisfaction on such interacting teams is usually high.

• In decentralized communication networks members communicate directly with one another.

Figure 8.5 Communication networks and interaction patterns found in teams.

When task demands allow for more independent work by team members, a centralized communication network is the best option. Also called the wheel network or chain network, it operates with a central “hub” through which one member, often a formal or informal team leader, collects and distributes information. Members of such coaching teams work on assigned tasks independently while the hub keeps everyone and everything coordinated. Work is divided up among members and results are pooled to create the finished product. The centralized network works well when team tasks are routine and easily subdivided. It is usually the hub member who experiences the most satisfaction on successful coacting teams.

• Centralized communication networks link group members through a central control point.

Counteracting teams form when subgroups emerge within a team due to issue-specific disagreements, such as a temporary debate over the best means to achieve a goal, or emotional disagreements, such as personality clashes. This creates a restricted communication network in which the subgroups contest each other's positions and restrict interactions with one another. The poor communication often creates problems. But there are times when it can be useful. Counteracting teams might be set up to stimulate conflict and criticism to help improve creativity or double check decisions about to be implemented.

• Restricted communication networks link subgroups that disagree with one another's positions.

Proxemics and Use of Space

An important but sometimes neglected part of communication in teams involves proxemics, or the use of space as people interact.21 We know, for example, that office or workspace architecture is an important influence on communication behavior. It only makes sense that communication in teams might be improved by arranging physical space to best support it. This might be done by moving chairs and tables closer together, or by choosing to meet in physical spaces that are most conducive to communication. Meeting in a small conference room at the library, for example, may be a better choice than meeting in a busy coffee shop.

• Proxemics involves the use of space as people interact.

Some architects and consultants specialize in office design for communication and teamwork. When Sun Microsystems built its San Jose, California, facility, public spaces were designed to encourage communication among persons from different departments. Many meeting areas had no walls, and most walls were glass.22 At Google headquarters, often called Googleplex, specially designed office “tents” are made of acrylics to allow both the sense of private personal space and transparency.23 And at b&a advertising in Dublin, Ohio, an emphasis on open space supports the small ad agency's emphasis on creativity; after all, its Web address is www.babrain.com. Face-to-face communication is the rule at b&a to the point where internal e-mail among employees is banned. There are no offices or cubicles, and all office equipment is portable. Desks have wheels so that informal meetings can happen by people repositioning themselves for spontaneous collaboration. Even the formal meetings are held standing up in the company kitchen.24

Communication Technologies

It hardly seems necessary in the age of Facebook, Twitter, and Skype to mention that teams now have access to many useful technologies that can facilitate communication and reduce the need to be face to face. We live and work in an age of instant messaging, tweets and texting, wikis, online discussions, video chats, videoconferencing, and more. We are networked socially 24–7 to the extent we want, and there's no reason the members of a team can't utilize the same technologies to good advantage.

Think of technology as allowing and empowering teams to use virtual communication networks in which team members communicate electronically all or most of the time. Technology in virtual teamwork acts as the “hub member” in the centralized communication network and as an ever-present “electronic router” that links members in decentralized networks on an as-needed and always-ready basis. And new developments with social media keep pushing these capabilities forward. General Electric, for example, started a “Tweet Squad” to advise employees how social networking could be used to improve internal collaboration. The insurer MetLife has its own social network, connect. MetLife, which facilitates collaboration through a Facebook-like setting.25

• Virtual communication networks link team members through electronic communication.

Of course and as mentioned in the last chapter, certain steps need to be taken to make sure that virtual teams and communication technologies are as successful as possible. This means doing things like online team-building so that members get to know one another, learn about and identify team goals, and otherwise develop a sense of cohesiveness.26 And we shouldn't forget protocols and everyday good manners when using technology as part of teamwork. For example, Richard Anderson, CEO of Delta Airlines, says: “I don't think it's appropriate to use Blackberrys in meetings. You might as well have a newspaper and open the newspaper up in the middle of the meeting.”27 Might we say the same for the texting now commonplace in classrooms?

Improving Team Decisions

LEARNING ROADMAP Ways Teams Make Decisions / Assets and Liabilities of Team Decisions / Groupthink Symptoms and Remedies / Team Decision Techniques

One of the most important activities for any team is decision making, the process of choosing among alternative courses of action. The quality and timeliness of decisions made and the processes through which they are arrived at can have an important impact on how teams work and what they achieve.

• Decision making is the process of choosing among alternative courses of action.

Ways Teams Make Decisions

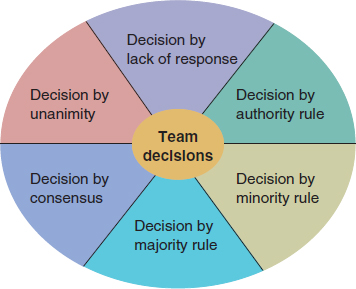

Consider the many teams of which you have been and are a part. Just how do major decisions get made? Most often there's a lot more going on than meets the eye. Edgar Schein, a noted scholar and consultant, has worked extensively with teams to identify, analyze, and improve their decision processes.28 He observes that teams may make decisions through any of six methods discussed here. Schein doesn't rule out any method, but he does point out their advantages and disadvantages.

Lack of Response In decision by lack of response one idea after another is suggested without any discussion taking place. When the team finally accepts an idea, all others have been bypassed and discarded by simple lack of response rather than by critical evaluation. This may happen early in a team's development when new members are struggling for identities and confidence. It's also common in teams with low-performance norms and when members just don't care enough to get involved in what is taking place. But whenever lack of response drives decisions, it's relatively easy for a team to move off in the wrong, or at least not the best, direction.

Figure 8.6 Alternative ways that teams make decisions.

Authority Rule In decision by authority rule the chairperson, manager, or leader makes a decision for the team. This is very time efficient and can be done with or without inputs by other members. Whether the decision is a good one or a bad one depends on if the authority figure has the necessary information and if other group members accept this approach. When an authority decision is made without expertise or member commitment, problems are likely.

Minority Rule In decision by minority rule two or three people are able to dominate, or “railroad,” the group into making a decision with which they agree. This is often done by providing a suggestion and then forcing quick agreement. The railroader may challenge the group with statements like: “Does anyone object? … No? Well, let's go ahead then.” While such forcing and bullying may get the team moving in a certain direction, member commitment to making the decision successful will probably be low. “Kickback” and “resistance,” especially when things get difficult, aren't unusual in these situations.

Majority Rule One of the most common ways that groups make decisions is through decision by majority rule. This usually takes place as a formal vote to find the majority viewpoint. When team members get into disagreements that seem irreconcilable, for example, voting is seen to be an easy way out of the situation. But, majority rule is often used without awareness of its potential problems. The very process creates coalitions, especially when votes are taken and results are close. Those in the minority—the “losers”—may feel left out or discarded without having had a fair say. They may not be enthusiastic about implementing the decision of the “winners.” Lingering resentments may hurt team effectiveness in the future if they become more concerned about winning the next vote than doing what is best for the team.

Consensus Another of the decision alternatives in Figure 8.6 is consensus. It results when discussion leads to one alternative being favored by most team members and other members agree to support it. When a consensus is reached, even those who may have opposed the chosen course of action know that they have been listened to and have had a fair chance to influence the outcome. Consensus does not require unanimity. What it does require is the opportunity for any dissenting members to feel that they have been able to speak and that their voices have been heard.29 Because of the extensive process involved in reaching a consensus decision, it may be inefficient from a time perspective. But consensus is veiy powerful in terms of generating commitments among members to making the final decision work best for the team.

• Consensus is a group decision that has the expressed support of most members.

Unanimity A decision by unanimity may be the ideal state of affairs. Here, all team members wholeheartedly agree on the course of action to be taken. This “logically perfect” decision situation is extremely difficult to attain in actual practice. One reason that teams sometimes turn to authority decisions, majority voting, or even minority decisions, in fact, is the difficulty of managing the team process to achieve decisions by consensus or unanimity.

When in Doubt, Follow the Seven Steps for Consensus

It's easy to say that consensus is good. It's a lot harder to achieve consensus, especially when tough decisions are needed. Here are some tips for how members should behave in consensus-seeking teams.

- Don't argue blindly; consider others' reactions to your points.

- Be open and flexible, but don't change your mind just to reach quick agreement.

- Avoid voting, coin tossing, and bargaining to avoid or reduce conflict.

- Act in ways that encourage everyone's involvement in the decision process.

- Allow disagreements to surface so that information and opinions can be deliberated.

- Don't focus on winning versus losing; seek alternatives acceptable to all.

- Discuss assumptions, listen carefully, and encourage participation by everyone.

Assets and Liabilities of Team Decisions

Just as with communication networks, the best teams don't limit themselves to any one of the decision methods just described. Rather, they move back and forth using each in appropriate circumstances. In our cases, for example, we never complain when a department head makes an authority decision to have a welcome reception for new students at the start of the academic year or calls for a faculty vote on a proposed new travel policy. Yet we'd quickly disapprove if a department head made an authority decision to hire a new faculty member—something we believe should be made by faculty consensus.

The key for the department head in our example and for any team leader is to use decision methods that best fit the problems and situations at hand. This requires a good understanding of the potential assets and liabilities of team decision making.30

On the positive side, the more team-oriented decision methods, such as consensus and unanimity, offer the advantages of bringing more information, knowledge, and expertise to bear on a problem. Extensive discussion tends to create broader understanding of the final decision, and this increases acceptance. It also strengthens the commitments of members to follow through and support the decision.

But as we all know, team decisions can be imperfect. It usually takes a team longer to make a decision than it does an individual. Then, too, social pressures to conform might make some members unwilling to go against or criticize what appears to be the will of the majority. And in the guise of a so-called team decision, furthermore, a team leader or a few members might “railroad” or “force” other members to accept their preferred decision.

GROUPTHINK AND MADAGASCAR

Cohesiveness is generally a good thing, but sometimes it can lead to problems. Groupthink occurs when group members fail to critically evaluate circumstances and proposed ideas. They don't actually lose the ability to criticize, they simply don't exercise it. Members go out of their way to conform, as cohesiveness actually works against the group.

In the movie Madagascar, four animals try to escape from the New York Central Zoo. Local residents complain about the danger, so the animals are shipped to Africa when they are captured. The animals' crates are tossed overboard during a storm and they end up in Madagascar.

Local King Julian, leader of the lemurs, hatches a plan to make friends with the mysterious animals that arrive on the island. He suggests that Alex the lion might be helpful in protecting them from other predators on the island. When Maurice, Julian's assistant, asks why predators are scared of Alex, he is quickly silenced. All the other lemurs are quick to agree with King Julian. But Alex is later discovered to be a hungry carnivore and banished from the lemur colony.

This movie segment shows how easy it is for dissension to be squelched in highly cohesive groups. King Julian, for example, demeans individuals that question his ideas or offer contrasting views. The scene also shows mind guarding. Acknowledging that Alex was a dangerous predator might force the lemurs to deal with an unpleasant reality, so they pretend it does not exist.

Get to Know Yourself Better Experiential Exercise 21, Work Team Dynamics, in the OB Skills Workbook can be a good gauge of whether your group/team is working effectively or might be susceptible to groupthink. Take a minute and assess a group to which you currently belong. If you are the leader, what can you do to guard against groupthink? If you are not the leader, what actions would you take if your team was heading toward groupthink?

Groupthink Symptoms and Remedies

An important potential problem that arises when teams try to make decisions is groupthink—the tendency of members in highly cohesive groups to lose their critical evaluative capabilities.31 As identified by social psychologist Irving Janis, groupthink is a property of highly cohesive teams, and it occurs because team members are so concerned with harmony that they become unwilling to criticize each other's ideas and suggestions. Desires to hold the team together, feel good, and avoid unpleasantries bring about an overemphasis on agreement and an underemphasis on critical discussion. This often results in a poor decision.

• Groupthink is the tendency of cohesive group members to lose their critical evaluative capabilities.

By way of historical examples Janis suggests that groupthink played a role in the U.S. forces' lack of preparedness at Pearl Harbor before the United States entered World War II. It has also been linked to flawed U.S. decision making during the Vietnam War, to events leading up to the space shuttle disasters, and, most recently, to failures of American intelligence agencies regarding the status of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Perhaps you can think of other examples from your own experiences where otherwise well-intentioned teams end up doing the wrong things.

The following symptoms of teams displaying groupthink should be well within the sights of any team leader and member.32

- Illusions of invulnerability—Members assume that the team is too good for criticism or beyond attack.

- Rationalizing unpleasant and disconfirming data—Members refuse to accept contradictory data or to thoroughly consider alternatives.

- Belief in inherent group morality—Members act as though the group is inherently right and above reproach.

- Stereotyping competitors as weak, evil, and stupid—Members refuse to look realistically at other groups.

- Applying direct pressure to deviants to conform to group wishes—Members refuse to tolerate anyone who suggests the team may be wrong.

- Self-censorship by members—Members refuse to communicate personal concerns to the whole team.

- Illusions of unanimity—Members accept consensus prematurely, without testing its completeness.

- Mind guarding—Members protect the team from hearing disturbing ideas or outside viewpoints.

Groupthink Can Be Avoided When Team Leaders and Team Members Follow These Tips

- Assign the role of critical evaluator to each team member.

- Have the leader avoid seeming partial to one course of action.

- Create subgroups that each work on the same problem.

- Have team members discuss issues with outsiders and report back.

- Invite outside experts to observe and react to team processes.

- Assign someone to be a “devil's advocate” at each team meeting.

- Hold “second-chance” meetings after consensus is apparently achieved.

There is no doubt that groupthink is a serious threat to the quality of decision making in teams at all levels and in all types of organizations. But it can be managed if team leaders and members are alert to the above symptoms and quick to take action to prevent harm.33 The accompanying sidebar identifies a number of steps to avoid groupthink or at least minimize its occurrence. For example, President Kennedy chose to absent himself from certain strategy discussions by his cabinet during the Cuban Missile Crisis. This reportedly facilitated critical discussion and avoided tendencies for members to try to figure out what the president wanted and then give it to him. As a result, the decision-making process was open and expansive, and the crisis was successfully resolved.

Team Decision Techniques

In order to take full advantage of the team as a decision-making resource, care must be exercised to avoid groupthink and otherwise manage problems in team dynamics. Team process losses often occur, for example, when meetings are poorly structured or poorly led as members try to work together. Decisions can easily get bogged down or go awry when tasks are complex, information is uncertain, creativity is needed, time is short, “strong” voices are dominant, and debates turn emotional and personal. These are times when special team decision techniques can be helpful.34

Brainstorming In brainstorming, team members actively generate as many ideas and alternatives as possible, and they do so relatively quickly and without inhibitions. IBM, for example, uses online brainstorming as part of a program called Innovation Jam. It links IBM employees, customers, and consultants in an “open source” approach. Says CEO Samuel J. Palmisano: “A technology company takes its most valued secrets, opens them up to the world and says, O.K., world, you tell us what to do with them.”35

• brainstorming involves generating ideas through “freewheeling” and without criticism.

You are probably familiar with the rules for brainstorming. First, all criticism is ruled out. No one is allowed to judge or evaluate any ideas until they are all on the table. Second, “freewheeling” is welcomed. The emphasis is on creativity and imagination; the wilder or more radical the ideas the better. Third, quantity is a goal. The assumption is that the greater the number, the more likely a superior idea will appear. Fourth, “piggy-backing” is good. Everyone is encouraged to suggest how others' ideas can be turned into new ideas or how two or more ideas can be joined into still another new idea.

Nominal Group Technique Teams sometimes get into situations where the opinions of members differ so much that antagonistic arguments develop during discussions. At other times teams get so large that open discussion and brainstorming are awkward to manage. In such cases a structured approach called the nominal group technique may be helpful in face to face or virtual meetings.36

• The nominal group technique involves structured rules for generating and prioritizing ideas.

The technique begins by asking team members to respond individually and in writing to a nominal question, such as: “What should be done to improve the effectiveness of this work team?” Everyone is encouraged to list as many alternatives or ideas as they can. Next, participants in round-robin fashion are asked to read or post their responses to the nominal question. Each response is recorded on large newsprint or in a computer database as it is offered. No criticism is allowed. The recorder asks for any questions that may clarify specific items on the list, but no evaluation is allowed. The goal is simply to make sure that everyone fully understands each response. A structured voting procedure is then used to prioritize responses to the nominal question and identify the choice or choices having most support. This procedure allows ideas to be evaluated without risking the inhibitions, hostilities, and distortions that may occur in an open and less structured team meeting.

Delphi Technique The Rand Corporation developed a third group-decision approach, the Delphi Technique, for situations when group members are unable to meet face to face. In this procedure, questionnaires are distributed online or in hard copy to a panel of decision makers. They submit initial responses to a decision coordinator. The coordinator summarizes the solutions and sends the summary back to the panel members, along with a follow-up questionnaire. Panel members again send in their responses, and the process is repeated until a consensus is reached and a clear decision emerges.

• The Delphi Technique involves generating decision-making alternatives through a series of survey questionnaires.

8 study guide

Key Questions and Answers

What are high-performance teams and how do we build them?

- Team-building is a collaborative approach to improving group process and performance.

- High-performance teams have core values, clear performance objectives, the right mix of skills, and creativity.

- Team-building is a data-based approach to analyzing group performance and taking steps to improve performance in the future.

- Team-building is participative and engages all group members in collaborative problem solving and action.

How can team processes be improved?

- Individual entry problems are common when new teams are formed and when new members join existing teams.

- Task leadership involves initiating, summarizing, and making direct contributions to the group's task agenda; maintenance leadership involves gate-keeping, encouraging, and supporting the social fabric of the group over time.

- Distributed leadership occurs when team members step in to provide helpful task and maintenance activities and discourage disruptive activities.

- Role difficulties occur when expectations for group members are unclear, overwhelming, underwhelming, or conflicting.

- Norms are the standards or rules of conduct that influence the behavior of team members; cohesiveness is the attractiveness of the team to its members.

- Members of highly cohesive groups value their membership and are very loyal to the group; they also tend to conform to group norms.

- The best situation is a team with positive performance norms and high cohesiveness; the worst is a team with negative performance norms and high cohesiveness.

- Inter-team dynamics are forces that operate between two or more groups as they cooperate and compete with one another.

How can team communications be improved?

- Effective teams vary their use of alternative communication networks and decision-making methods to best meet task and situation demands.

- Interacting groups with decentralized networks tend to perform well on complex tasks; co-acting groups with centralized networks may do well at simple tasks.

- Restricted communication networks are common in counteracting groups where subgroups form around disagreements.

- Wise choices on proxemics, or the use of space, can help teams improve communication among members.

- Information technology ranging from instant messaging, video chats, video conferencing, and more, can improve communication in teams, but it must be well used.

How can team decisions be improved?

- Teams can make decisions by lack of response, authority rule, minority rule, majority rule, consensus, and unanimity.

- Although team decisions often make more information available for problem solving and generate more understanding and commitment, their potential liabilities include social pressures to conform and greater time requirements.

- Groupthink is a tendency of members of highly cohesive teams to lose their critical evaluative capabilities and make poor decisions.

- Special techniques for team decision making include brainstorming, the nominal group technique, and the Delphi technique.

Terms to Know

Brainstorming (p. 189)

Centralized communication network (p. 184)

Cohesiveness (p. 179)

Collective intelligence (p. 171)

Consensus (p. 186)

Decentralized communication network (p. 183)

Decision making (p. 185)

Delphi Technique (p. 190)

Disruptive behavior (p. 175)

Distributed leadership (p. 174)

Groupthink (p. 188)

Inter-team dynamics (p. 180)

Maintenance activities (p. 175)

Nominal group technique (p. 190)

Norms (p. 176)

Performance norm (p. 177)

Proxemics (p. 184)

Restricted communication network (p. 184)

Role (p. 175)

Role ambiguity (p. 176)

Role conflict (p. 176)

Role negotiation (p. 176)

Role overload (p. 176)

Role underload (p. 176)

Rule of conformity (p. 179)

Task activities (p. 175)

Team-building (p. 171)

Virtual communication networks (p. 185)

Self-Test 8

Multiple Choice

- One of the essential criteria of a true team is _____. (a) large size (b) homogeneous membership (c) isolation from outsiders (d) collective accountability

- The team-building process can best be described as participative, data-based, and _____. (a) action-oriented (b) leader-centered (c) ineffective (d) short-term

- A person facing an ethical dilemma involving differences between personal values and the expectations of the team is experiencing _____ conflict. (a) person-role (b) intrasender role (c) intersender role (d) interrole

- The statement “On our team, people always try to do their best” is an example of a(n) _____ norm. (a) support and helpfulness (b) high-achievement (c) organizational pride (d) personal improvement

- Highly cohesive teams tend to be _____. (a) bad for organizations (b) good for members (c) good for social loafing (d) bad for norm conformity

- To increase team cohesiveness, one would _____. (a) make the group bigger (b) increase membership diversity (c) isolate the group from others (d) relax performance pressures

- A team member who does a good job at summarizing discussion, offering new ideas, and clarifying points made by others is providing leadership by contributing _____ activities to the group process. (a) required (b) disruptive (c) task (d) maintenance

- When someone is being aggressive, makes inappropriate jokes, or talks about irrelevant matters in a group meeting, these are all examples of _____ that can harm team performance. (a) disruptive behaviors (b) maintenance activities (c) task activities (d) role dynamics

- If you heard from an employee of a local bank that “it's a tradition here for us to stand up and defend the bank when someone criticizes it,” you could assume that the bank employees had strong _____ norms. (a) support and helpfulness (b) organizational and personal pride (c) ethical and social responsibility (d) improvement and change

- What can be predicted when you know that a work team is highly cohesive? (a) high-performance results (b) high member satisfaction (c) positive performance norms (d) status congruity

- When two groups are in competition with one another, _____ may be expected within each group. (a) greater cohesiveness (b) less reliance on the leader (c) poor task focus (d) more conflict

- A co-acting group is most likely to use a(n) _____ communication network. (a) interacting (b) decentralized (c) centralized (d) restricted

- A complex problem is best dealt with by a team using a(n) _____ communication network. (a) all-channel (b) wheel (c) chain (d) linear

- The tendency of teams to lose their critical evaluative capabilities during decision making is a phenomenon called _____. (a) groupthink (b) the slippage effect (c) decision congruence (d) group consensus

- When a team decision requires a high degree of commitment for its implementation, a(n) _____ decision is generally preferred. (a) authority (b) majority rule (c) consensus (d) minority rule

Short Response

- 16. Describe the steps in a typical team-building process.

- 17. How can a team leader build positive group norms?

- 18. How do cohesiveness and conformity to norms influence team performance?

- 19. How can inter-team competition be bad and good for organizations?

Applications Essay

- 20. Alejandro Puron recently encountered a dilemma in working with his employer's diversity task force. One of the team members claimed that a task force must always be unanimous in its recommendations. “Otherwise,” she said, “we will not have a true consensus.” Alejandro, the current task force leader, disagrees. He believes that unanimity is desirable but not always necessary to achieve consensus.

Question You are a management consultant specializing in teams and teamwork. Alejandro asks for advice. What would you tell him and why?

Next Steps