Zappos Insights: Revealing Corporate Secrets

Tony Hsieh doesn't see the need to protect the secrets to Zappos's wild success. In fact, the CEO is happy to share them with anyone who comes by the office.

Hsieh has built a $635 million Internet superstore by doing two things very well: exceeding customers' expectations and driving positive word-of-mouth recommendations. Hsieh believes so strongly in the organizational culture that he's on a mission to share it with anyone who will listen.

It all comes together In a program called Zappos Insights. The core experience is a tour of Zappos's headquarters. “Company Evangelists” lead groups of 20 around the cubicles, overflowing with kitschy action figures and brightly colored balloons. Staffers blow horns and ring cowbells to greet participants in the 16 weekly tours, and each department tries to offer a more outlandish welcome than the last.a

“We open our doors and say, 'Be part of our family and talk to anybody you want.' And you see it's the real deal.” —Robert Richman, co-leader of Zappos Insights.d

The tours are free, but many visitors actually come for paid one-and two-day seminars that immerse participants in the Zappos culture. The capstone of the two-day boot camp is dinner at Tony Hsieh's house, with ample time to talk customer service with the CEO himself. Seminars range from $497 to $3,997. “There are management consulting firms that charge really high rates,” says Hsieh. “We wanted to come up with something that's accessible to almost any business.”b

Those who want to learn Zappos's secrets without venturing to Las Vegas have a few options. You can subscribe to a members-only community that grants access to video interviews and chats with Zappos management or get a free copy of Zappos Family Culture Book about Zappos's mission and core values.

They may be giving away hard-earned knowledge, but Zappos definitely isn't losing money—profits from the seminars pay for the program, and Hsieh hopes it will someday represent 10 percent of Zappos's operating profit. “There's a huge open market,” says Robert Richman, co-leader of Zappos Insights. “We were afraid that we've been talking about this for free for so long. 'Are people going to be upset we are charging for it?' Instead, the reaction is opposite.”c

Quick Summary

- In addition to free tours of their Las Vegas headquarters, Zappos now offers one-and two-day seminars. Attendees immerse themselves in Zappos's culture, which CEO Tony Hsieh believes is inseparable from the company's success.

- Attendees have unprecedented one-on-one access to Zappos executives and managers, all of whom are happy to espouse the customer and employee-centric policies that increase profits and retain employees year after year.

- While the project is in its infancy, Hsieh hopes to develop Zappos's management consulting business into a venture that earns 10 percent of annual profits.

FYI: Customers from over 30 countries have attended Zappos Insights seminars.e

13 Leadership Essentials

the key point

Not all managers are leaders and not all leaders are managers. In a managerial position, being a leader requires understanding how to adapt one's management style to the situation to generate willing and effective followership. As shown in the Zappos example, the most successful leaders are those who are able to generate strong cultures in which employees work together to get things done.

chapter at a glance

What Is Leadership?

What Are Situational Contingency Approaches to Leadership?

What Are Follower-Centered Approaches to Leadership?

What Are Inspirational and Relational Leadership Perspectives?

Leadership

LEARNING ROADMAP Managers versus Leaders / Trait Leadership Perspectives / Behavioral Leadership Perspectives

Most people assume that anyone in management, particularly the CEO, is a leader. Currently, however, controversy has arisen over this assumption. We can all think of examples where managers do not perform much, if any, leadership, as well as instances where leadership is performed by people who are not in management. Researchers have even argued that failure to clearly recognize this difference is a violation of “truth in advertising” because many studies labeled “leadership” may actually be about “management.”1

Managers versus Leaders

A key way of differentiating between managers and leaders is to argue that the role of management is to promote stability or to enable the organization to run smoothly, whereas the role of leadership is to promote adaptive or useful changes.2 Persons in managerial positions could be involved with both management and leadership activities, or they could emphasize one activity at the expense of the other. Both management and leadership are needed, however, and if managers do not assume responsibility for both, then they should ensure that someone else handles the neglected activity. The point is that when we discuss leadership, we do not assume it is identical to management.

For our purposes, we treat leadership as the process of influencing others to understand and agree about what needs to be done and how to do it, and the process of facilitating individual and collective efforts to accomplish shared objecttives.3 Leadership appears in two forms: (1) formal leadership, which is exerted by persons appointed or elected to positions of formal authority in organizations, and (2) informal leadership, which is exerted by persons who become influential because they have special skills that meet the needs of others. Although both types are important in organizations, this chapter will emphasize formal leadership; informal leadership will be addressed in the next chapter.4

• Leadership is the process of influencing others and the process of facilitating individual and collective efforts to accomplish shared objectives.

The leadership literature is vast—thousands of studies at last count—and consists of numerous approaches.5 We have grouped these approaches into two chapters: Leadership Essentials, Chapter 13, and Leadership Challenges and Organizational Change, Chapter 14. The present chapter focuses on trait and behavioral theory perspectives, cognitive and symbolic leadership perspectives, and transformational and charismatic leadership approaches. Chapter 14 deals with such leadership challenges as how to be a moral leader, how to share leadership, how to lead across cultures, how to be a strategic leader of major units, and, of course, how to lead change. Many of the perspectives in each chapter include several models. Although each of these models may be useful to you in a given work setting, we invite you to mix and match them as necessary in your setting, just as we did earlier with the motivational models discussed in Chapter 5.

Change Brings Out the Leader in Us

Avon CEO Andrea Jung feels “there is a big difference between being a leader and being a manager.” That difference lies in being flexible and willing to change. According to Jung, if you have difficulty with change you will have a harder time being successful as a leader.

Trait Leadership Perspectives

For over a century, scholars have attempted to identify the key characteristics that separate leaders from nonleaders. Much of this work stressed traits. Trait perspectives assume that traits play a central role in differentiating between leaders and nonleaders in that leaders must have the “right stuff.”6 The great person-trait approach reflects the attempt to use traits to separate leaders from nonleaders. This list of possible traits identified only became longer as researchers focused on the leadership traits linked to successful leadership and organizational performance. Unfortunately, few of the same traits were identified across studies. Part of the problem involved inadequate theory, poor measurement of traits, and the confusion between managing and leading.

• Trait perspectives assume that traits play a central role in differentiating between leaders and nonleaders or in predicting leader or organizational outcomes.

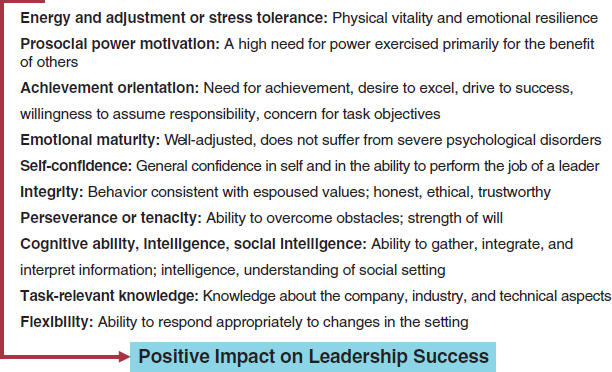

Fortunately, recent research has yielded promising results. A number of traits have been found that help identify important leadership strengths, as outlined in Figure 13.1. As it turns out, most of these traits also tend to predict leadership outcomes.7

Key traits of leaders include ambition, motivation, honesty, self-confidence, and a high need for achievement. They crave power not as an end in itself but as a means to achieve a vision or desired goals. At the same time, they must have enough emotional maturity to recognize their own strengths and weaknesses, and have to be oriented toward self-improvement. Furthermore, to be trusted, they must have authenticity; without trust, they cannot hope to maintain the loyalty of their followers. Leaders are not easily discouraged, and they stick to a chosen course of action as they push toward goal accomplishment. At the same time, they must be able to deal with the large amount of information they receive on a regular basis. They do not need to be brilliant, but usually exhibit above-average intelligence. In addition, leaders have a good understanding of their social setting and possess extensive knowledge concerning their industry, firm, and job.

Figure 13.1 Traits with positive implications for successful leadership.

Even with these traits, however, the individual still needs to be engaged. To lead is to influence others, and so we turn to the question of how a leader should act.

Behavioral Leadership Perspectives

How should managerial leaders act toward subordinates? The behavioral perspective assumes that leadership is central to performance and other outcomes. However, instead of underlying traits, behaviors are considered. Two classic research programs—at the University of Michigan and at the Ohio State University—provide useful insights into leadership behaviors.

• The behavioral perspective assumes that leadership is central to performance and other outcomes.

Michigan Studies In the late 1940s, researchers at the University of Michigan sought to identify the leadership pattern that results in effective performance. From interviews of high-and low-performing groups in different organizations, the researchers derived two basic forms of leader behaviors: employee-centered and production-centered. Employee-centered supervisors are those who place strong emphasis on their subordinates' welfare. In contrast, production-centered supervisors are more concerned with getting the work done. In general, employee-centered supervisors were found to have more productive workgroups than did the production-centered supervisors.8

These behaviors are generally viewed on a continuum, with employee-centered supervisors at one end and production-centered supervisors at the other. Sometimes, the more general terms human-relations oriented and task oriented are used to describe these alternative leader behaviors.

Ohio State Studies At about the same time as the Michigan studies, an important leadership research program began at the Ohio State University. A questionnaire was administered in both industrial and military settings to measure subordinates' perceptions of their superiors' leadership behavior. The researchers identified two dimensions similar to those found in the Michigan studies: consideration and initiating structure.9 A highly considerate leader was found to be one who is sensitive to people's feelings and, much like the employee-centered leader, tries to make things pleasant for his or her followers. In contrast, a leader high in initiating structure was found to be more concerned with defining task requirements and other aspects of the work agenda; he or she might be seen as similar to a production-centered supervisor. These dimensions are related to what people sometimes refer to as socioemotional and task leadership, respectively.

- A leader high in consideration is sensitive to people's feelings.

- A leader high in initiating structure is concerned with spelling out the task requirements and clarifying aspects of the work agenda.

At first, the Ohio State researchers believed that a leader high in consideration, or socioemotional warmth, would have more highly satisfied or better performing subordinates. Later results suggested, however, that many individuals in leadership positions should be high in both consideration and initiating structure. This dual emphasis is reflected in the leadership grid approach.

• Leadership grid is an approach that uses a grid that places concern for production on the horizontal axis and concern for people on the vertical axis.

The Leadership Grid Robert Blake and Jane Mouton developed the leadership grid approach based on extensions of the Ohio State dimensions. Leadership grid results are plotted on a nine-position grid that places concern for production on the horizontal axis and concern for people on the vertical axis, where 1 is minimum concern and 9 is maximum concern. As an example, those with a 1/9 style—low concern for production and high concern for people—are termed “country club management.” They do not emphasize task accomplishment but stress the attitudes, feelings, and social needs of people.10

Similarly, leaders with a 1/1 style—low concern for both production and people—are termed “impoverished,” while a 5/5 style is labeled “middle of the road.” A 9/1 leader—high concern for production and low concern for people— has a “task management” style. Finally, a 9/9 leader, high on both dimensions, is considered to have a “team management” style; this is the ideal leader in Blake and Mouton's framework.

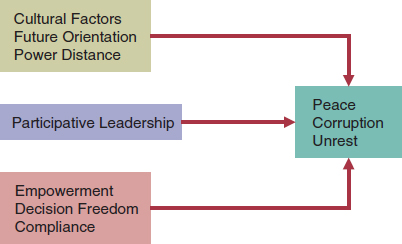

RESEARCH INSIGHT

Participatory Leadership and Peace

In an unusual cross-cultural organizational behavior study, Gretchen Spreitzer examined the link between business leadership practices and indicators of peace in nations. She found that earlier research suggested that peaceful societies had (1) open and egalitarian decision making and (2) social control processes that limit the use of coercive power. These two characteristics are the hallmarks of participatory systems that empower people in the collective. Spreitzer reasoned that business firms can provide open egalitarian decisions by stressing participative leadership and empowerment.

Spreitzer recognized that broad cultural factors could also be important. The degree to which the culture is future oriented and power distance appeared relevant. And she reasoned that she needed specific measures of peace. She selected two major indicators: (1) the level of corruption and (2) the level of unrest. The measure of unrest was a combined measure of political instability, armed conflict, social unrest, and international disputes. While she found a large leadership database that directly measured participative leadership, she developed the measures of empowerment from another apparently unrelated survey. Two items appeared relevant: the decision freedom individuals reported (decision freedom), and the degree to which they felt they had to comply with their boss regardless of whether they agreed with an order (compliance).

You can schematically think of this research in terms of the following model.

As one might expect with exploratory research, the findings support most of her hypotheses but not all. Participative leadership was related to less corruption and less unrest, as was the future-oriented aspect of culture. Regarding empowerment, there were mixed results; decision freedom was linked to less corruption and unrest, but the compliance measure was only linked to more unrest.

Do the Research Do you agree that when business used participatory leadership, it legitimated the democratically based style and increased the opportunity for individuals to express their voice? What other research could be done to determine the link between leadership and peace?11

Source: Gretchen Spreitzer, “Giving Peace a Chance: Organizational Leadership, Empowerment, and Peace,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 28 (2007), pp. 1077-1095.

Cross-Cultural Implications It is important to consider whether the findings of the Michigan, Ohio State, and grid studies transfer across national boundaries. Some research in the United States, Britain, Hong Kong, and Japan shows that the behaviors must be carried out in different ways in alternative cultures. For instance, British leaders are seen as considerate if they show subordinates how to use equipment, whereas in Japan the highly considerate leader helps subordinates with personal problems.12 We will see this pattern again as we discuss other theories. The concept seems to transfer across boundaries, but the actual behaviors differ. Sometimes the differences are slight, but in other cases they are not. Even subtle differences in the leader's situation can make a significant difference in precisely the type of behavior needed for success. Successful leaders adjust their influence attempts to the situation.

Situational Contingency Leadership

LEARNING ROADMAP Fiedler's Leadership Contingency View / Path-Goal View of Leadership/ Hersey and Blanchard Situational Leadership Model/ Substitutes for Leadership

The trait and behavioral perspectives assume that leadership, by itself, would have a strong impact on outcomes. Another development in leadership thinking has recognized, however, that leader traits and behaviors can act in conjunction with situational contingencies—other important aspects of the leadership situation—to predict outcomes. Traits are enhanced by their relevance to the leader's situational contingencies.13 For example, achievement motivation should be most effective for challenging tasks that require initiative and the assumption of personal responsibility for success. Leader flexibility should be most predictive in unstable environments or when leaders lead different people over time.

Prosocial power motivation, or power oriented toward benefiting others, is likely to be most important in situations where decision implementation requires lots of persuasion and social influence. “Strong” or “weak” situations also make a difference. An example of a strong situation is a highly formal organization with lots of rules, procedures, and policies. An example of a weak situation is one that is ambiguous and unstructured. In a strong situation traits will have less impact than in a weaker, more unstructured situation because the leader has less ability to influence the nature of the situation. In other words, leaders can't show dynamism as much when the organization restricts them.

• Prosocial power motivation is power oriented toward benefiting others.

Traits may also make themselves felt by influencing leader behaviors (e.g., a leader high in energy engages in directive, take-charge behaviors).14 In an attempt to isolate when particular traits and specific combinations of leader behavior and situations are important, scholars have developed a number of situational contingency theories and models. Some of these theories emphasize traits, whereas others deal exclusively with leader behaviors and the setting.

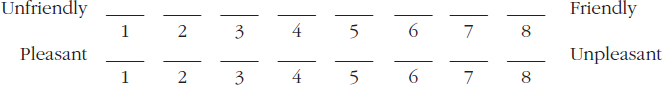

Fiedler's Leadership Contingency View

Fred Fiedler's leadership contingency view argues that team effectiveness depends on an appropriate match between a leader's style, essentially a trait measure, and the demands of the situation.15 Specifically, Fiedler considers situational control—the extent to which a leader can determine what his or her group is going to do—and leader style as important in determining the outcomes of the group's actions and decisions.

• Situational control is the extent to which leaders can determine what their groups are going to do and what the outcomes of their actions are going to be.

To measure a person's leadership style, Fiedler uses an instrument called the least-preferred co-worker (LPC) scale. Respondents are asked to describe the person with whom they have been able to work least well—their least preferred co-worker, or LPC—using a series of adjectives such as the following two:

• The least-preferred co-worker (LPC) scale is a measure of a person's leadership style based on a description of the person with whom respondents have been able to work least well.

Fiedler argues that high-LPC leaders (those describing their LPC very positively) have a relationship-motivated style, whereas low-LPC leaders have a task-motivated style. Because LPC is a style and does not change across settings, the leaders' actions vary depending on the degree of situational control. Specifically, a task-motivated leader (low LPC) tends to be nondirective in high-and low-control situations, and directive in those in between. A relationship-motivated leader tends to be the opposite. Confused? Take a look at Figure 13.2 to clarify the differences between high-LPC leaders and low-LPC leaders.

Figure 13.2 shows the task-motivated leader as being more effective when the situation is high and low control, and the relationship-motivated leader as being more effective when the situation is moderate control. The figure also shows that Fiedler measures situational control with the following variables:

- Leader-member relations (good/poor)—membership support for the leader

- Task structure (high/low)—spelling out the leader's task goals, procedures, and guidelines in the group

- Position power (strong/weak)—the leader's task expertise and reward or punishment authority

Figure 13.2 Fiedler's situational variables and their preferred leadership styles.

Consider an experienced and well-trained production supervisor of a group that is responsible for manufacturing a part for a personal computer. The leader is highly supported by his group members and can grant raises and make hiring and firing decisions. This supervisor has very high situational control and is operating in situation 1 in Figure 13.2. For such high-control situations, a task-oriented leader style is predicted as the most effective. Now consider the opposite setting. Think of the chair of a student council committee of volunteers who are unhappy about this person being the chair. They have the low-structured task of organizing a Parents' Day program to improve university-parent relations. This low-control situation also calls for a task-motivated leader who needs to behave directively to keep the group together and focus on the task; in fact, the situation demands it. Finally, consider a well-liked academic department chair who is in charge of determining the final list of students who will receive departmental honors at the end of the academic year. This is a moderate-control situation with good leader-member relations, low-task structure, and weak position power, calling for a relationship-motivated leader. The leader should emphasize nondirective and considerate relationships with the faculty.

Fiedler's Cognitive Resource Perspective Fiedler later developed a cognitive resource perspective that built on his earlier model.16 Cognitive resources are abilities or competencies. According to this approach, whether a leader should use directive or nondirective behavior depends on the following situational contingencies: (1) the leader's or subordinates' ability or competency, (2) stress, (3) experience, and (4) group support of the leader. Cognitive resource theory is useful because it directs us to leader or subordinate group-member ability, an aspect not typically considered in other leadership approaches.

The theory views directiveness as most helpful for performance when the leader is competent, relaxed, and supported. In this case, the group is ready, and directiveness is the clearest means of communication. When the leader feels stressed, his or her attention is diverted. In this case, experience is more important than ability. If support is low, then the group is less receptive, and the leader has less impact. Group-member ability becomes most important when the leader is nondirective and receives strong support from group members. If support is weak, then task difficulty or other factors have more impact than either the leader or the subordinates.

Evaluation and Application The roots of Fiedler's contingency approach date back to the 1960s and have elicited both positive and negative reactions. The biggest controversy concerns exactly what Fiedler's LPC instrument measures. Some question Fiedler's behavioral interpretations that link the style measure with leader behavior in all eight conditions. Furthermore, the approach makes the most accurate predictions in situations 1 and 8 and 4 and 5; results are less consistent in the other situations.17 Tests regarding cognitive resources have shown mixed results.18

In terms of application, Fiedler has developed leader match training, which Sears, Roebuck and Co. and other organizations have used. Leaders are trained to diagnose the situation in order to “match” their LPC score. The red arrows in Figure 13.2 suggest a “match.” In cases with no “match,” the training shows how each of these situational control variables can be changed to obtain a match. For instance, a leader with a low LPC and in setting 4 could change the position power to strong and gain a “match.” Another way of getting a match is through leader selection or placement based on LPC scores.19 For example, a low LPC leader would be selected for a position with high situational control, as in our earlier example of the manufacturing supervisor. A number of studies have been designed to test this leader match training. Although they are not uniformly supportive, more than a dozen such tests have found increases in group effectiveness following the training.20

- In leader match training, leaders are trained to diagnose the situation to match their high and low LPC scores with situational control.

LOOKING FOR LEADER MATCH AT GOOGLE

The news came as a surprise: Eric Schmidt was out as CEO of Google, and Larry Page was in. Schmidt had been brought in by board of directors in 2001 to provide “adult supervision” to then 27-year-old founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin. For 10 years Google's management structure was described as something of a three-ring circus, with co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin running the business behind the scenes, and Schmidt as the public face. Now, the three decided, it was time for Page to take the stage.

“For the last 10 years, we have all been equally involved in making decisions. This triumvirate approach has real benefits in terms of shared wisdom, and we will continue to discuss the big decisions among the three of us. But we have also agreed to clarify our individual roles so there's clear responsibility and accountability at the top of the company,” said Eric Schmidt.

The objective is to simplify the management structure and speed up decision making. “Larry will now lead product development and technology strategy, his greatest strengths … and he will take charge of our day-to-day operations as Google's Chief Executive Officer,” according to Schmidt.

That leaves Sergey Brin, with title of co-founder, to focus on strategic projects and new products, and Schmidt to serve as executive chairman, working externally on deals, partnerships, customers, and government outreach. As described on the official Google blog, “We are confident that this focus will serve Google and our users well in the future.”

In many ways, Page is taking over at an ideal time. Google's business is doing well, with the company reporting revenues of $29.3 billion, up 24 percent from the year before and profits soaring. But the concern isn't for the present; it is for the future. As reported in Newsweek, “there has been a gnawing sense that Google's best days may be behind it.” Google is facing tough competition from Facebook and Microsoft, and has been losing top talent to younger tech shops.

Page's job is clear: Shake things up and knock loose some new ideas. But it's a risky move. As reported in Newsweek, “Page is a computer scientist, not a business strategist. And not all founders make great leaders. Page is no Steve Jobs.”

Steve Jobs or not, Page is a brilliant entrepreneur who has been heavily involved in running the business and gets along well with the engineers. The question now is whether the new leadership structure will work, and if Google has found its match between leader capabilities and company needs.

We conclude that although unanswered questions concerning Fiedler's contingency theory remain, especially concerning the meaning of LPC, the perspective and the leader match program have relatively strong support.21 The approach and training program are especially useful in encouraging situational contingency thinking.

Path-Goal View of Leadership

Another well-known approach to situational contingencies is one developed by Robert House based on the earlier work of others.22 House's path-goal view of managerial leadership has its roots in the expectancy model of motivation discussed in Chapter 5. The term path-goal is used because of its emphasis on how a leader influences subordinates' perceptions of both work goals and personal goals, and the links, or paths, found between these two sets of goals.

• Path-goal view of managerial leadership assumes that a leader's key function is to adjust his or her behaviors to complement situational contingencies.

The theory assumes that a leader's key function is to adjust his or her behaviors to complement situational contingencies, such as those found in the work setting. House argues that when the leader is able to compensate for things lacking in the setting, subordinates are likely to be satisfied with the leader. For example, the leader could help remove job ambiguity or show how good performance could lead to an increase in pay. Performance should improve as the paths by which (1) effort leads to performance—expectancy—and (2) performance leads to valued rewards—instrumentality—become clarified.

House's approach is summarized in Figure 13.3. The figure shows four types of leader behavior (directive, supportive, achievement-oriented, and participative) and two categories of situational contingency variables (follower attributes and work-setting attributes). The leader behaviors are adjusted to complement the situational contingency variables in order to influence subordinate satisfaction, acceptance of the leader, and motivation for task performance.

Before delving into the dynamics of the House model, it is important to understand each component. Directive leadership has to do with spelling out the subordinates' tasks; it is much like the initiating structure mentioned earlier. Supportive leadership focuses on subordinate needs and well-being and on promoting a friendly work climate; it is similar to consideration. Achievement-oriented leadership emphasizes setting challenging goals, stressing excellence in performance, and showing confidence in the group members' ability to achieve high standards of performance. Participative leadership focuses on consulting with subordinates, and seeking and taking their suggestions into account before making decisions.

• Directive leadership spells out the what and how of subordinates' tasks.

• Supportive leadership focuses on subordinate needs, well-being, and promotion of a friendly work climate.

- Achievement-oriented leadership emphasizes setting goals, stressing excellence, and showing confidence in people's ability to achieve high standards of performance.

- Participative leadership focuses on consulting with subordinates and seeking and taking their suggestions into account before making decisions.

Figure 13.3 Summary of major path-goal relationships in House's leadership approach.

Important subordinate characteristics are authoritarianism (close-mindedness, rigidity), internal-external orientation (i.e., locus of control), and ability. The key work-setting factors are the nature of the subordinates' tasks (task structure), the formal authority system, and the primary workgroup.

Predictions from Path-Goal Theory Directive leadership is predicted to have a positive impact on subordinates when the task is ambiguous; it is predicted to have just the opposite effect for clear tasks. In addition, the theory predicts that when ambiguous tasks are being performed by highly authoritarian and closed-minded subordinates, even more directive leadership is called for.

Supportive leadership is predicted to increase the satisfaction of subordinates who work on highly repetitive tasks or on tasks considered to be unpleasant, stressful, or frustrating. In this situation the leader's supportive behavior helps compensate for adverse conditions. For example, many would consider traditional assembly-line jobs to be highly repetitive, perhaps even unpleasant or frustrating. A supportive supervisor could help make these jobs more enjoyable. Achievement-oriented leadership is predicted to encourage subordinates to strive for higher performance standards and to have more confidence in their ability to meet challenging goals. For subordinates in ambiguous, nonrepetitive jobs, achievement-oriented leadership should increase their expectations that effort leads to desired performance.

Participative leadership is predicted to promote satisfaction on nonrepetitive tasks that allow for the ego involvement of subordinates. For example, on a challenging research project, participation allows employees to feel good about dealing independently with the demands of the project. On repetitive tasks, open-minded or nonauthoritarian subordinates will also be satisfied with a participative leader. On a task where employees screw nuts on bolts hour after hour, for example, those who are nonauthoritarian will appreciate having a leader who allows them to get involved in ways that may help break up the monotony.

Evaluation and Application House's path-goal approach has been with us for more than 30 years. Early work provided some support for the theory in general and for the particular predictions discussed earlier.23 However, current assessments by well-known scholars have pointed out that many aspects have not been tested adequately, and there is very little current research concerning the theory.24 House recently revised and extended path-goal theory into the theory of work-unit leadership. It's beyond our scope to discuss the details of this new theory, but as a base the new theory expands the list of leader behaviors beyond those in path-goal theory, including aspects of both leadership theory and emerging challenges of leadership.25 It remains to be seen how much research it will generate.

In terms of application there is enough support for the original path-goal theory to suggest two possibilities. First, training could be used to change leader-ship behavior to fit the situational contingencies. Second, the leader could be taught to diagnose the situation and learn how to try to change the contingencies, as in leader match.

Hersey and Blanchard Situational Leadership Model

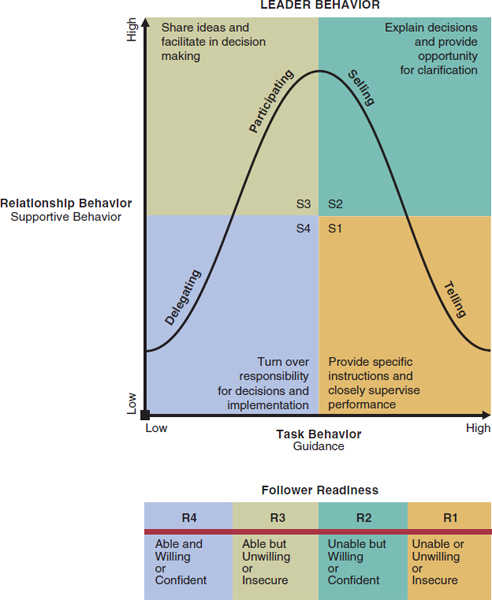

Like other situational contingency approaches, the situational leadership model developed by Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard indicates that there is no single best way to lead.26 Hersey and Blanchard focus on the situational contingency of maturity, or “readiness,” of followers, in particular. Readiness is the extent to which people have the ability and willingness to accomplish a specific task. Hersey and Blanchard argue that “situational” leadership requires adjusting the leader's emphasis on task behaviors—for instance, giving guidance and direction— and relationship behaviors—for example, providing socioemotional support— according to the readiness of followers to perform their tasks. Figure 13.4 identifies four leadership styles: delegating, participating, selling, and telling. Each emphasizes a different combination of task and relationship behaviors by the leader. The figure also suggests the following situational matches as the best choice of leadership style for followers at each of four readiness levels.

• The situational leadership model focuses on the situational contingency of maturity or “readiness” of followers.

PATH-GOAL AND REMEMBER THE TITANS

A leader following the Path-Goal View will adjust her or his style in response to a number of situations that may exist. If followers lack ability, a directive style might be used. If the work is unpleasant, a supportive approach is needed. Achievement-oriented and participative styles can be used to increase follower motivation. A leader must be aware of the conditions that exist and help clear the paths that lead followers to achieve goals (both individual and organizational).

In Remember the Titans, legendary Coach Herman Boone (Denzel Washington) has a daunting task. In assuming the position of head football coach at the newly integrated T.C. Williams High School, he demonstrates Path-Goal leadership. Boone knows that many of the players will not respect a “colored” coach. When it comes to practice, he uses a very directive leadership style-my way or else, get the plays right or expect to run. At the same time, he respects the difficulties his players face. When Louie Lastik (Ethan Suplee) says he does not have the grades to go to college, Boone whispers that they will work on his grades together because he does not want that to keep Lastik from going to college. “Let's just keep that between you and me” he adds at the end.

Herman Boone clearly knew when to be tough and when to use a softer, more understanding approach. He was clearly the leader, making tough decisions even in situations involving assistant coaches and star players. Still, he recognized the impact his leadership would have on the lives of the young men who played for him.

Get to Know Yourself Better Coach Boone was an effective coach because he knew what it took to get a team in shape and meet the individual needs of his players. What about you? Complete Assessment 11, Leadership Style, in the OB Skills Workbook to see if your concern for task is balanced in terms of your concern for people. Too much emphasis on one aspect over the other could lead to problems. Can you show enough concern for individuals and still keep them focused on getting the job done?

A “telling” style (S1) is best for low follower readiness (R1). The direction provided by this style defines roles for people who are unable and unwilling to take responsibility themselves; it eliminates any insecurity about the task that must be done.

Figure 13.4 Hersey and Blanchard model of situational leadership.

A “selling” style (S2) is best for low-to-moderate follower readiness (R2). This style offers both task direction and support for people who are unable but willing to take task responsibility; it involves combining a directive approach with explanation and reinforcement in order to maintain enthusiasm.

A “participating” style (S3) is best for moderate-to-high follower readiness (R3). Able but unwilling followers require supportive behavior in order to increase their motivation; by allowing followers to share in decision making, this style helps enhance the desire to perform a task.

A “delegating” style (S4) is best for high readiness (R4). This style provides little in terms of direction and support for the task at hand; it allows able and willing followers to take responsibility for what needs to be done.

This situational leadership approach requires that the leader develop the capability to diagnose the demands of situations and then choose and implement the appropriate leadership response. The model gives specific attention to followers and their feelings about the task at hand and suggests that effective leaders focus on emerging changes in the level of readiness of the people involved in the work.

In spite of its considerable history and incorporation into training programs by a large number of firms, this situational leadership approach has received very little systematic research attention.27

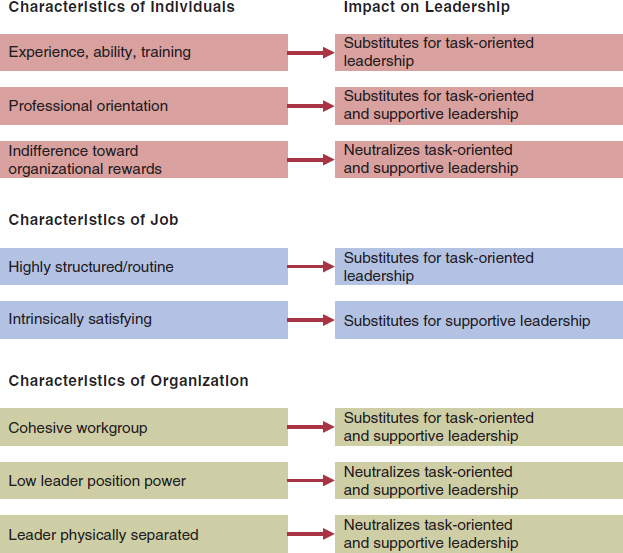

Substitutes for Leadership

A final situational contingency approach is leadership substitutes.28 Scholars using this approach have developed a perspective indicating that sometimes managerial leadership makes essentially no difference. These researchers contend that certain individuals, jobs, and organization variables can serve as substitutes for leadership or neutralize a managerial leader's impact on subordinates. Some examples of these variables are shown in Figure 13.5.

Substitutes for leadership make a leader's influence either unnecessary or redundant in that they replace the leader's influence. For example, in Figure 13.5 it will be unnecessary and perhaps impossible for a leader to provide the kind of task-oriented direction already available from an experienced, talented, and well-trained subordinate. In contrast, neutralizers can prevent a leader from behaving in a certain way or nullify the effects of a leader's actions. If a leader has little formal authority or is physically separated, for example, his or her leadership may be neutralized even though task supportiveness may still be needed.

• Substitutes for leadership make a leader's influence either unnecessary or redundant in that they replace a leader's influence.

Figure 13.5 Some examples of leadership substitutes and neutralizers.

Research suggests some support for the general notion of substitutes for leadership.29 First, studies involving Mexican, U.S., and Japanese workers suggests both similarities and differences between various substitutes in the countries examined. Again, there were subtle but important differences across the national samples. Second, a systematic review of 17 studies found mixed results for the substitutes theory. The review suggested a need to broaden the list of substitutes and leader behaviors. It was also apparent that the approach is especially important in examining self-directed work teams. In such teams, for example, in place of a hierarchical leader specifying standards and ways of achieving goals (task-oriented behaviors), the team might set its own standards and substitute them for those of the leader's.

Central to the substitutes for leadership perspective is the question of whether leadership makes a difference at all levels of the organization. At least one researcher has suggested that at the very top of today's complex firms, the leader-ship of the CEO makes little difference compared to environmental and industry forces.30 These leaders are typically accountable to so many groups of people for the resources they use that their leadership impact is greatly constrained, so the argument goes. Instead of a dramatic and an important effect, much of the impact a top leader has is little more than symbolic. Further, much of what is described as CEO leadership is actually part of explanations to legitimize their actions.

Such symbolic treatment of leadership occurs particularly when performance is either extremely high or extremely low or when the situation is such that many people could have been responsible for the performance. The late James Meindl and his colleagues call this phenomenon the romance of leadership, whereby people attribute romantic, almost magical, qualities to leadership.31 Consider the firing of a baseball manager or football coach whose team does not perform well. Neither the owner nor anyone else is really sure why the poor showing occurred. But the owner can't fire all the players, so a new team manager is brought in to symbolize “a change in leadership” that is “sure to turn the team around.”

• Romance of leadership involves people attributing romantic, almost magical, qualities to leadership.

Follower-Centered Approaches

LEARNING ROADMAP Implicit Leadership Theories / Implicit Followership Theories

So far we have dealt with leader traits, leader behavior, and the situations facing the leader and his or her subordinates. But what about followers and their part in the leadership process? Interestingly, until very recently, issues of followership have been largely ignored in leadership research. It seems that our fascination with leaders has caused us to overlook the importance of followers. As discussed in this section, this issue is addressed in cognitive approaches to leadership, but is also becoming its own field of study in newly emerging work on followership.

Implicit Leadership Theories (ILTs)

In the mid-1970s, Dov Eden and Uri Leviatan32 wrote an article in which they concluded that “leadership factors are in the mind of the respondent.” This radical idea sparked what is known as the cognitive revolution in leadership, in which researchers recognized that if leadership resides in the minds of followers, then it is imperative to discover what followers are thinking.33

Scholars began using cognitive categorization theory to learn more about how followers process information regarding leaders.34 Recall from Chapter 4 on perception and attribution that cognitive categorization is a type of mental shortcut that helps us simplify our cognitive understanding of the world by attaching labels when we are faced with a stimulus target. For example, think about your first day of class. Did you look around the room and find yourself making assessments of the teacher, and even your classmates? Were your assessments accurate? This is the process of cognitive categorization, and it occurs automatically and spontaneously when individuals categorize others on the basis of visually salient cues (e.g., age, race, gender, and appearance) and social roles (e.g., leader and follower). We do it because it helps us process and act on information quickly and easily.

Leadership Categorization Theory In leadership research, these ideas developed into leadership categorization theory. According to this theory, individuals naturally classify people as leaders or nonleaders using implicit theories. Implicit leadership theories are preconceived notions about the attributes (e.g., traits and behaviors) associated with leaders.35 They reflect the structure and content of “cognitive categories” used to distinguish leaders from nonleaders.

• Implicit leadership theories are preconceived notions about the attributes associated with leaders that reflect the structure and content of “cognitive categories” used to distinguish leaders from nonleaders.

These attributes, or leadership prototypes, are mental images of the characteristics that make a “good” leader, or that a “real” leader would possess. Individuals engage in a two-stage categorization process.36 First, relevant prototypes, such as those shown in Table 13.1, are activated and the target person is compared with the prototype. Second, the target person is categorized as a leader or nonleader depending on the fit with the prototype.37

• Prototypes are a mental image of the characteristics that comprise an implicit theory.

For example, think of someone you consider to be a great leader. Make a list of attributes you associate with that person as a leader. These images that come to mind represent your implicit theory of leadership. The words you listed represent your “prototypes” for effective leadership. Now look at Table 13.1. Are the attributes you listed in the table? Chances are they are in the list, which is a measure of the implicit leadership theories developed in research by Lynn Offermann and colleagues.38

Table 13.1 Implicit Leadership Theories Prototypes

| Prototype | Description |

| Sensitivity | Sympathetic, sensitive, compassionate, understanding |

| Dedication | Dedicated, disciplined, prepared, hard-working |

| Tyranny | Domineering, power-hungry, pushy, manipulative |

| Charisma | Charismatic, inspiring, involved, dynamic |

| Attractiveness | Attractive, classy, well-dressed, tall |

| Masculinity | Male, masculine |

| Intelligence | Intelligent, clever, knowledgeable, wise |

| Strength | Strong, forceful, bold, powerful |

Source: Offermann, L. R., Kennedy, John K., Jr., & Wirtz, P. W. (1994). Implicit leadership theories: Content, structure, and generalizability. Leadership Quarterly, 5, 43–58.

Through sampling individuals about their implicit theories, research has identified eight predominant factors, both positive and negative, in peoples' images of leaders: sensitivity, dedication, tyranny, charisma, attractiveness, masculinity, intelligence, and strength. The prototypes show that people view leaders in a positive fashion and hold them to high standards. However, the negative prototypes also reveal that people recognize the possibility for leaders, who are in positions of power, to use that power negatively, such as to dominate, control, and manipulate others.

Since these factors were developed from an American sample, we should expect differences in prototypes by country and by national culture. For example, a typical business leader prototype in Japan is described as responsible, educated, trustworthy, intelligent, and disciplined, whereas the counterpart in the United States is portrayed as determined, goal-oriented, verbally skilled, industrious, and persistent.39 More in-depth insights on such prototypes, as related to culture, are provided by the broadscale Project GLOBE discussed in the next chapter.

Implicit Followership Theories

Although research on implicit theories has been around since the early 1980s, it wasn't until 2010 that these ideas were applied to followers. This work is now rapidly developing as the study of followership. Followership is defined as the behaviors of individuals acting in relation to leaders.40 To understand these behaviors, researchers are investigating whether an association exists between followers' implicit theories and the nature of their interactions with leaders.

• Followership is defined as the behaviors of individuals acting in relation to leaders.

Followership Categorization Theory Paralleling the approach described earlier in leadership categorization theory, Dr. Thomas Sy developed a measure of implicit followership theory (IFT) that we can refer to as followership categorization theory.41 Again using the concept of implicit theories, this research gathered the prototypical behavior of followers as described by leaders.

• Implicit followership theories are preconceived notions about prototypical and antiprototypical followership behaviors and characteristics.

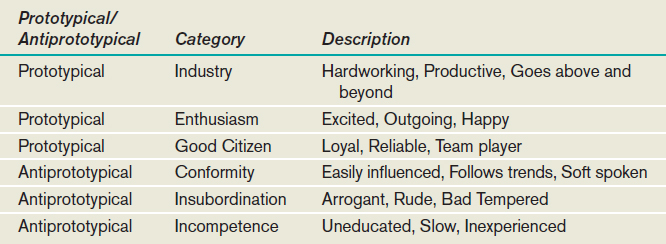

Using a sample of managers, the investigator asked leaders to identify characteristics associated with effective followers, ineffective followers, and subordinates. He then analyzed the responses to see whether categories of prototypes emerged. The result, as shown in Table 13.2, is an 18-item implicit followership theory (IFT) scale that contains two main factors: followership prototype and followership antiprototype. Followership prototype consists of factors associated with good followers, including being “industrious,” having enthusiasm, and being a good organizational citizen. Followership antiprototype consists of behaviors associated with ineffective followership, including conformity, insubordination, and incompetence.

Table 13.2 Implicit Followership Theories Prototypes and Antiprototypes

: Source: Sy, T. (2010). What do you think of followers? Examining the content, structure, and consequences of implicit followership theories. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 113(2), 73–84.

: Source: Sy, T. (2010). What do you think of followers? Examining the content, structure, and consequences of implicit followership theories. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 113(2), 73–84.

Although this work is very new, it has important practical implications. For example, if we think about leaders and recognize they have implicit theories of followers represented by follower prototypes, these prototypes may play a key role in shaping leaders' judgments of and reactions to followers. Remember that categorization processes are spontaneous and automatic. This suggests that leaders make assessments of followers very quickly and very early on in the relationship. Followers who fulfill leaders' prototypes will be judged more positively than those who match the follower antiprototype. It could also be that leaders' implicit followership theories (IFTs) may predispose them to certain socioemotional experiences. For example, leaders who endorse more prototypic perceptions of followers may be more likely to generate more positive affective tones in their workgroups, whereas leaders who endorse more antiprototypic perceptions of followers may generate more negative emotion with the group.

The Social Construction of Followership Using a somewhat different approach, Melissa Carsten and colleagues are exploring followership through a lens of “social construction.”42 According to social construction approaches, individual behavior is “constructed” in context, as people act and interact in situations. Social constructions are influenced by two things: the individuals' implicit theories about how they should act, and the nature of the situation in which they find themselves. For example, have you ever been in situations where you think you should do one thing but find yourself doing another? This is because your implicit belief is interacting with the situation to influence your behavior.

• Social construction approaches describe individual behavior as “constructed” in context, as people act and interact in situations.

Using a social construction approach, Carsten and colleagues found that followers tend to act in different ways according to their beliefs and the context. Some followers hold passive beliefs, viewing their roles in the classic sense of following—as passive, deferential, and obedient to authority (i.e., a passive belief). Others hold proactive beliefs, viewing their role as expressing opinions, taking initiative, and constructively questioning and challenging leaders (i.e., a proactive belief). These proactive followership beliefs more closely resemble leading (e.g., followers acting as leaders) than following. Not surprisingly, proactive beliefs were found to be strong among “high potentials”—people who have been identified by their organizations as demonstrating the skills and capabilities to be promoted to higher-level leadership positions in their organization. This makes sense. It suggests that one key to advancement in organizations is being able to demonstrate the ability to lead not only downward, but upward.

• Passive followership beliefs are beliefs that followers should be passive, deferent, and obedient to authority.

• Proactive followership beliefs are beliefs that followers should express opinions, take initiative, and constructively question and challenge leaders.

Because social construction is dependent on context, findings also show that not everyone is able to act according to their followership beliefs. This occurs when the work environment does not support the belief. Individuals holding proactive beliefs reported they could not be proactive when they were operating in authoritarian or bureaucratic work climates because these environments suppressed their ability to take the initiative and speak up. In this environment they were frustrated—they felt stifled and were not able to work to their potential. Alternatively, individuals with passive beliefs reported cases where an empowering climate encouraged them to offer ideas and opinions, but these situations were uncomfortable because their natural inclinations as followers were to follow rather than be empowered. They were stressed by leaders' demands that they be more proactive, and weren't comfortable engaging in those behaviors. These cases of mismatch created dissonance for these individuals, leading to varying levels of stress and discontent.

Although this work is still developing, similar to discussions of the importance of person-job fit, when the mismatch between one's followership beliefs and the work context is ongoing and pervasive it is likely to create strong feelings of dissonance. These feelings can be detrimental to workplace functioning, such as making one dissatisfied or highly stressed in their job, and potentially leading to high levels of burnout.

Inspirational and Relational Leadership Perspectives

LEARNING ROADMAP Charismatic Leadership / Transactional and Transformational Leadership / Leader-Member Exchange Theory

The role of the follower is also considered in inspirational and relational perspectives to leadership. Like follower-centered approaches, these perspectives consider how followers view and interact with leaders.

Charismatic Leadership

One of the reasons leadership is considered so important is simply because most of us think of leaders as highly inspirational individuals—heroes and heroines. We think of prominent individuals who appear to have made a significant difference by inspiring followers to work toward great accomplishments. In the study of leadership, this inspirational aspect has been studied extensively under the notions of charismatic leadership.

Studies of charismatic leadership have provided an extensive body of evidence indicating that charismatic leaders, by force of their personal abilities, are capable of having a profound and extraordinary effect on followers.43 Findings show that charismatic leaders are high in need for power and have high feelings of self-efficacy and conviction in the moral rightness of their beliefs. Their need for power motivates them to want to be leaders, and this need is then reinforced by their conviction of the moral rightness of their beliefs. The feeling of self-efficacy, in turn, makes these individuals believe they are capable of being leaders. These traits also influence such charismatic behaviors as role modeling, image building, articulating simple and dramatic goals, emphasizing high expectations, showing confidence, and arousing follower motives.

• Charismatic leaders are those leaders who are capable of having a profound and extraordinary effect on followers.

Some of the more interesting and important work based on aspects of charismatic theory involves a study of U.S. presidents.44 The research showed that behavioral charisma was substantially related to presidential performance and that the kind of personality traits described in the theory, along with response to crisis among other things, predicted behavioral charisma for the sample of presidents.45

The charisma trait also has a potential negative side as seen in infamous leaders such as Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin, who had been considered charismatic. Negative, or “dark-side,” charismatic leaders emphasize personalized power and focus on themselves—whereas positive, or “bright-side,” charismatic leaders emphasize socialized power that tends to positively empower their followers.46 This helps explain the differences between a dark-side leader such as David Koresh, leader of the Branch Davidian sect, and a bright-side leader such as Martin Luther King Jr.47

Jay Conger and Rabindra Kanungo have developed a three-stage charismatic leadership model.48 In the initial stage the leader critically evaluates the status quo. Deficiencies in the status quo lead to formulations of future goals. Before developing these goals, the leader assesses available resources and constraints that stand in the way of the goals. The leader also assesses follower abilities, needs, and satisfaction levels. In the second stage, the leader formulates and articulates the goals along with an idealized future vision. Here, the leader emphasizes articulation and impression-management skills. Then, in the third stage, the leader shows how these goals and the vision can be achieved. The leader emphasizes innovative and unusual means to achieve the vision.

Martin Luther King Jr. illustrated these three stages in his nonviolent civil rights approach, thereby changing race relations in this country. Conger and Kanungo have argued that if leaders use behaviors such as vision articulation, environmental sensitivity, and unconventional behavior, rather than maintaining the status quo, followers will tend to attribute charismatic leadership to them. Such leaders are also seen as behaving quite differently from those labeled “non-charismatic.”49

Transactional and Transformational Leadership

Building on notions originated by James MacGregor Burns, as well as on ideas from charismatic leadership theory, Bernard Bass has developed an approach that focuses on both transactional and transformational leadership.50

Transactional Leadership Transactional leadership involves leader-follower exchanges necessary for achieving routine performance agreed upon between leaders and followers. Transactional leadership is similar to most of the leadership approaches mentioned earlier. These exchanges involve four dimensions:

- Contingent rewards—various kinds of rewards in exchange for mutually agreed-upon goal accomplishment.

- Active management by exception—watching for deviations from rules and standards and taking corrective action.

- Passive management by exception—intervening only if standards not met.

- Laissez-faire—abdicating responsibilities and avoiding decisions.

• Transactional leadership involves leader-follower exchanges necessary for achieving routine performance agreed upon between leaders and followers.

Transformational leadership goes beyond this routine accomplishment, however. For Bass, transformational leadership occurs when leaders broaden and elevate their followers' interests, when they generate awareness and acceptance of the group's purposes and mission, and when they stir their followers to look beyond their own self-interests to the good of others.

Transformational Leadership Transformational leadership has four dimensions: charisma, inspiration, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Charisma provides vision and a sense of mission, and it instills pride along with follower respect and trust. For example, Steve Jobs, who founded Apple Computer, showed charisma by emphasizing the importance of creating the Macintosh as a radical new computer and has since followed up with products such as the iPod, iPhone, and iPad.

• Transformational leadership occurs when leaders broaden and elevate followers' interests and stir followers to look beyond their own interests to the good of others.

• Charisma provides vision and a sense of mission, and it instills pride along with follower respect and trust.

Inspiration communicates high expectations, uses symbols to focus efforts, and expresses important purposes in simple ways. As an example, in the movie Patton, George C. Scott stood on a stage in front of his troops with a wall-sized American flag in the background and ivory-handled revolvers in holsters at his side. Soldiers were told not to die for their country but make the enemy die for theirs. Intellectual stimulation promotes intelligence, rationality, and careful problem solving. For instance, your boss encourages you to look at a very difficult problem in a new way. Individualized consideration provides personal attention, treats each employee individually, and coaches and advises. This occurs, for example, when your boss drops by and makes remarks reinforcing your worth as a person.

• Inspiration communicates high expectations, uses symbols to focus efforts, and expresses important purposes in simple ways.

• Intellectual stimulation promotes intelligence, rationality and careful problem solving, by for example, encouraging looking at a very difficult problem in a new way.

• Individualized consideration provides personal attention, treats each employee individually, and coaches and advises.

Bass concludes that transformational leadership is likely to be strongest at the top-management level, where there is the greatest opportunity for proposing and communicating a vision. However, for Bass, it is not restricted to the top level; it is found throughout the organization. Furthermore, transformational leadership operates in combination with transactional leadership. Leaders need both transformational and transactional leadership in order to be successful, just as they need to display both leadership and management abilities.51

Reviews have summarized a large number of studies using Bass's transformational approach. These reviews report significant favorable relationships between Bass's leadership dimensions and various aspects of performance and satisfaction, as well as extra effort, burnout and stress, and predispositions to act as innovation champions on the part of followers. The strongest relationships tend to be associated with charisma or inspirational leadership, although in most cases the other dimensions are also important. These findings are consistent with those reported elsewhere.52 They broaden leadership outcomes beyond those cited in many leadership studies.

Issues in Charismatic and Transformational Leadership In respect to leaders and leadership development, it is reasonable to ask: Can people be trained in charismatic/transformational leadership? According to research in this area, the answer is yes. Bass and his colleagues have put a lot of work into developing such training efforts. For example, they have created a workshop where leaders are given initial feedback on their scores on Bass's measures. The leaders then devise improvement programs to strengthen their weaknesses and work with the trainers to develop their leadership skills. Bass and Avolio report findings that demonstrate the beneficial effects of this training. They also report the effectiveness of team training and programs tailored to individual firms' needs.53 Similarly, Conger and Kanungo propose training to develop the kinds of behaviors summarized in their model.

Approaches with special emphasis on vision often emphasize training. Kouzes and Posner report results of a week-long training program at AT&T. The program involved training leaders on five dimensions oriented around developing, communicating, and reinforcing a shared vision. According to Kouzes and Posner, leaders showed an average 15 percent increase in these visionary behaviors 10 months after participating in the program.54 Similarly, Sashkin and Sashkin have developed a leadership approach that emphasizes various aspects of vision and organizational culture change. They discuss a number of ways to train leaders to be more visionary and to enhance cultural change.55 All of these leadership training programs involve a heavy handson workshop emphasis so that leaders do more than just read about vision.

CEO PAY-IS IT EXCESSIVE?

In corporate America today, there seems to be a perception that CEOs have a tremendous influence on company success, whereas workers are more or less interchangeable. In fact, CEO compensation is typically over 260 times greater than the compensation provided to the median full-time employee. A typical CEO will earn more in one workday than the average worker will earn all year.

While the pay gap between top executives and the average American worker has traditionally been relatively large, it has grown tremendously over the past few decades. For the decade 1995-2005, CEO compensation rose nearly 300 percent while the average employee salary rose less than 5 percent-both occurring during a timeframe in which average corporate profits rose by a little over 100 percent.

In support of rising CEO salaries, the argument has been made that companies have to pay a lot to attract the best executive talent and need to pay for performance. However, pay levels are now such that many CEOs are assured of getting rich no matter how the company performs. In fact, over 80 percent of executives receive bonuses even during down years for the stock market.

In the midst of the recent economic downturn, one might expect this gap to be significantly reduced. Surprisingly, though, that has not occurred, and the pay gap remains very high by historical standards. Many people continue to be shocked by the exorbitant salaries and bonuses received by top executives, especially at a time when many companies are laying off employees and freezing salaries among lower-level workers.

An underlying question seems to be whether it is ethical for a company to eliminate hundreds or thousands of jobs while its CEO remains very highly compensated.

What Do You Think? Is it ethical for executives to reap such high rewards when employees are being laid off and shareholders are seeing little to no return on their investment? Should CEO pay be capped at some multiple of the average worker's pay? Should CEOs be forced to take a pay cut during this difficult financial period? What are the consequences (both positive and negative) of unrestricted CEO salaries? If you were the CEO of a company that was struggling financially and was in the process of laying off thousands of employees, would you voluntarily give up some of your compensation?

A second issue in leadership and leadership development involves this question: Is charismatic/transformational leadership always good? As pointed out earlier, dark-side charismatics, such as Adolf Hitler, can have a negative effect on followers. Similarly, charismatic/transformational leadership is not always helpful. Sometimes emphasis on a vision diverts energy from more important day-to-day activities. It is also important to note that such leadership by itself is not sufficient. That leadership needs to be used in conjunction with all of the leadership theories discussed in this chapter. Finally, charismatic and transformational leadership is important not only at the top of an organization. A number of experts argue that for an organization to be successful, it must apply at all levels of organizational leadership.

Leader-Member Exchange Theory

While charismatic and inspirational theories emphasize leader behavior, relational leadership theories adopt a different perspective: They view leadership as produced in the relationship between leaders and followers. The most prominent of these theories is leader-member exchange (LMX) theory.

• Leader-member exchange (LMX) theory emphasizes the quality of the working relationship between leaders and followers.

LMX theory shows that leaders develop differentiated relationships with subordinates in their work groups.56 Some relationships are high-quality (high LMX) “partnerships,” characterized by mutual influence, trust, respect, and loyalty. These relationships are associated with more challenging job assignments, increased leader attention and support, and more open and honest communication. Other relationships are low quality (low LMX), more in line with traditional supervisory relationships. Low-quality relationships are characterized by formal status and strict adherence to rules of the employment contract. They have low levels of interaction, trust, and support.

According to LMX theory, leadership is generated when leaders and followers are able to develop “incremental influence” with one another that produces behavior above and beyond what is required by the work contract. Returning to our discussion of managers and leaders at the beginning of the chapter, we can state that LMX approaches assume that managers are leaders when, through development of high-quality relationships, they are able to generate “willing followership” with subordinates in their work unit.

These differentiated relationships are important for subordinates because they have strong associations with work outcomes.57 Research shows that high-quality LMX is associated with increased follower satisfaction and productivity, decreased turnover, increased salaries, and faster promotion rates. Low-quality relationships are associated with negative work outcomes, including low job satisfaction and commitment, greater feelings of unfairness, lower performance, and higher stress. Recent discussions of LMX suggest that to generate strong leadership, managers should try to develop high-quality relationships with all subordinates.

The LMX approach continues to receive increasing emphasis in organizational behavior research literature worldwide. The evidence for the benefits of high-quality relationships is robust, and the implications for both managers and employees are quite clear. Relationships matter, and working to develop them— whether you are a leader or a follower—is critical in terms of both organizational and personal career outcomes.

13 study guide

Key Questions and Answers

What is leadership?

- Leadership is the process of influencing others to understand and agree about what needs to be done and how to do it, and the process of facilitating individual and collective efforts to accomplish shared objectives.

- Leadership and management differ in that management is designed to promote stability or to make the organization run smoothly, whereas the role of leadership is to promote adaptive change.

- Trait or great-person approaches argue that leader traits have a major impact on differentiating between leaders and nonleaders or predicting leadership outcomes.

- Traits are considered relatively innate and hard to change.

- Similar to trait approaches, behavioral theories argue that leader behaviors have a major impact on outcomes.

- The Michigan and Ohio State approaches are important leader behavior theories.

- Leader behavior theories are especially suitable for leadership training.

What is situational contingency leadership?

- Leader situational contingency approaches argue that leadership, in combination with various situational contingency variables, can have a major impact on outcomes.

- The effects of traits are enhanced to the extent of their relevance to the situational contingencies faced by the leader.

- Strong or weak situational contingencies influence the impact of leadership traits.

- Fiedler's contingency theory, House's path-goal theory, Hersey and Blanchard's situational leadership theory, and substitutes for leadership theory are particularly important specific situational contingency approaches.

- Sometimes, as in the case of the substitutes for leadership approach, the role of situational contingencies replaces that of leadership, so that leadership has little or no impact in itself.

What are follower-centered approaches to leadership?

- Follower-centered approaches focus on how followers view leaders and how they view themselves. The former are called implicit leadership theories (ILTs), and the latter are called implicit followership theories (IFTs).

- Implicit leadership theories (ILTs) are part of leadership categorization theory. They describe the cognitive categorization processes individuals use to identify characteristics, or prototypes, of traits and behaviors they associate with leaders (and nonleaders).

- Typical prototypes of leaders are sensitivity, dedication, tyranny, charisma, attractiveness, masculinity, intelligence, and strength. They reflect both the positive and negative elements of leaders.

- Followership is defined as the behaviors of individuals acting in relation to leaders. Followership categorization theory is the study of implicit followership theories that leaders hold of followers.

- Prototypical follower behaviors have been identified as industriousness (e.g., hard-working), having enthusiasm, and being a good citizen. Follower antiprototypes include conformity, insubordination, and incompetence.

- Implicit followership theories have also been studied relative to social constructions of follower roles. Social construction approaches consider individuals' beliefs regarding how they should act and the contexts in which they act.

- Social construction perspectives of followership have identified passive and proactive followership beliefs. Passive beliefs are consistent with classic definitions of followers as obedient, passive, and deferential, while proactive beliefs reflect include expressing opinions, taking the initiative, and constructively challenging leaders.

What are inspirational and relational leadership perspectives?

- Inspirational and relational leadership perspectives focus on how leaders motivate and build relationships with followers to achieve performance beyond expectations.

- Particularly important among inspirational approaches are Bass's transformational/ transactional theory and House's and Conger and Kanungo's charismatic perspectives.

- Transformational behaviors include charisma, inspiration, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Transactional behaviors include contingent reward, management-by-exception, and laissez-faire leadership.

- Charismatic/transformational leadership is not always good, as shown by the example of Adolf Hitler.

- The most prominent relational leadership theory is leader-member exchange (LMX).

- LMX describes how leaders develop relationships with some subordinates that are high quality and some that are low quality. Subordinates in high-quality relationships receive much better benefits and outcomes than those in low-quality LMX.

- The most effective leaders should develop high-quality relationships with all subordinates.

Terms to Know

Achievement-oriented leadership (p. 300)

Behavioral perspective (p. 294)

Charisma (p. 311)

Charismatic leaders (p. 309)

Consideration (p. 294)

Directive leadership (p. 300)

Followership (p. 307)

Implicit followership theories (IFTs) (p. 307)

Implicit leadership theories (ILTs) (p. 306)

Individualized consideration (p. 311)

Initiating structure (p. 294)

Inspiration (p. 311)

Intellectual stimulation (p. 311)

Leader match training (p. 298)

Leader-member exchange (LMX) theory (p. 313)

Leadership (p. 292)

Leadership grid (p. 294)

Least-preferred co-worker (LPC) scale (p. 297)

Participative leadership (p. 300)

Passive followership beliefs (p. 308)

Path-goal view of managerial leadership (p. 300)

Proactive followership beliefs (p. 308)

Prosocial power motivation (p. 296)

Prototypes (p. 306)

Romance of leadership (p. 305)

Situational control (p. 297)

Situational leadership model (p. 301)

Social construction (p. 308)

Substitutes for leadership (p. 304)

Supportive leadership (p. 300)

Trait perspectives (p. 293)

Transactional leadership (p. 310)

Transformational leadership (p. 310)

Self-Test 13