Evaluation

Introduction

Although we have made only passing reference to evaluation so far, in fact, evaluation should permeate the whole process of analysis, design, development and teaching to support online learning and assessment. In this chapter we will introduce some concepts and strategies to help you to do this in simple ways that are not too demanding in terms of the resources you will need, including your time.

We begin by introducing a few evaluation concepts, including some older ideas from the educational evaluation literature, and some more recent ones that relate directly to evaluation of the use of educational technology. We emphasise the value of a cyclical approach which provides an overarching framework that can encompass all of the other evaluation concepts and methods that you choose to use. A cyclical approach also supports the idea that online design, development and implementation is an incremental, iterative process that will involve you in continual refinement of your teaching practice as you draw on the evidence available to you through experience and evaluation. Two other important concepts in this context are the importance of reflection, as part of this cycle, and also the value of taking a pragmatic approach to evaluation. We will expand on these ideas in the next section.

After we have considered these concepts, we will focus specifically on online learning design, development and implementation, suggesting some evaluation methods that you could implement at each of these stages. With these ideas in mind, we will then highlight components that you might consider in designing your evaluation plan, taking into account the purpose and audience of your evaluation. This will include appropriate learner-centred evaluation methods if your purpose is associated with the improvement of student learning. After this we suggest some issues that you might need to address in managing, implementing, reporting and acting on the results of your evaluation.

Once you have established an approach to evaluation that works for you, you should have in place a simple, practical, cyclical framework which draws on the idea of reflective practice to guide you in the iterative improvement of your online teaching and assessment practices.

Some evaluation concepts

The educational evaluation literature has developed rapidly over recent decades, introducing many new concepts that are useful in guiding evaluation. We will only be covering a few of them here, with a particular emphasis on evaluation of educational technology. Underpinning these newer concepts is the seminal work of Scriven (1967) who conceptualised evaluation as a form of inquiry undertaken primarily to determine the worth of something, and of Stufflebeam (1972) who conceptualised evaluation as an aid to decision-making. These two concepts will probably inform any evaluation you undertake to improve your online teaching or assessment practices. Scriven (1967) was also responsible for identifying the concepts of formative and summative evaluation:

When the cook tastes the soup, it is formative evaluation; when the dinner guest tastes the soup, it is summative evaluation. (Harvey, 1998, p. 7)

When you are developing online teaching or assessment components, formative evaluation is critical: the time, effort and possibly the cost involved mean that it is vital that you build in formative evaluation at various points to ensure that the emerging online learning environment will allow students to meet the learning objectives successfully.

Another ‘old’ but useful idea is that of evaluation as illumination (Parlett & Hamilton, 1977). Referring to evaluation in a classroom context, they explained the approach as follows:

It aims to be both adaptable and eclectic. The choice of research tactics follows not from research doctrine, but from decisions in each case as to the best available techniques: the problem defines the methods used, not vice versa. (Parlett & Hamilton, 1977, p. 13)

This idea has been used effectively over recent years by the United States Teaching, Learning and Technology (TLT) Group in its Flashlight Program, conveying the idea of shining a light on whatever it is that needs to be evaluated. The latest version of Flashlight Online uses a Web 2.0 tool (The TLT Group, 2009). With its emphasis on eclecticism and pragmatism, it also closely resembles the concept recommended by Reeves and Hedberg (2003) who suggest using an ‘Eclectic-Mixed Methods-Pragmatic Paradigm’ when evaluating educational technology as this approach is most capable of handling the complexities of society and technology. At a narrower level, an eclectic and pragmatic approach acknowledges the need for adaptability to support the specific decisions that need to be made in specific contexts which are characteristic of educational evaluation.

As we noted earlier, it is also useful to consider evaluation as part of an ongoing cycle. This is often used as a quality-control approach involving:

Student evaluations of teaching effectiveness frequently use this kind of approach for quality assurance purposes. They are increasingly being used in higher education institutions around the world, often in conjunction with major government initiatives to enhance institutional accountability for benchmarking purposes (Marsh, 2007). Although not usually focused on evaluation of online learning, you could include evaluation data of this kind in the design of your evaluation plan which we will discuss later.

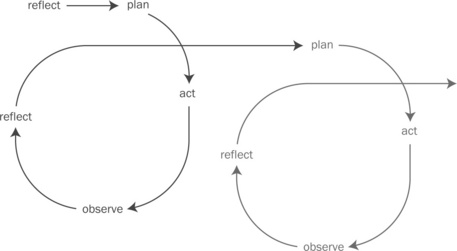

A cyclical approach also fits well with conceptualising the design, development and implementation of online learning and assessment approaches as an iterative process when you are designing your own evaluation strategies. In this way, evaluation can be seen in the context of an action research cycle (Figure 5.1). Kember (2000, p. 20) refers to seven features of action research which make it appropriate for quality enhancement in education. It is:

The ‘reflect’ part of the cycle indicated in Figure 5.1 is particularly important because it allows you and others involved to process the results gained from various evaluation strategies and determine what improvements you will make. A similar approach to evaluation, developed separately from the concept of action research, involves the ideas of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action (Schön, 1983; 1987) which are often used for evaluation in relation to professional education because they allow for the ‘messiness’ of the real world. Again, this suggests a pragmatic approach that lends itself well to evaluation during preparation and implementation of online learning and assessment.

Evaluation and online learning design, development and implementation

During the 1990s there were some useful contributions to developing an integrated approach to evaluation for educational technology projects, using a staged approach through design, development, implementation and institutionalisation (Alexander & Hedberg, 1994; Bain, 1999). A third framework, derived from these, was subsequently used by Phillips, Bain, McNaught, Rice and Tripp (2000) in an Australian national project on learning-centred evaluation of computer-facilita ted learning projects in higher education. In Table 5.1 we have adapted some elements of these frameworks to provide you with examples of the purpose of evaluation during design, development and implementation, the kinds of evaluation questions you might ask, and the methods you might use for answering them at each stage.

Table 5.1

An integrated evaluation framework

Source: Adapted from Alexander & Hedberg, 1994; Bain, 1999; Phillips et al., 2000.

![]() The examples just provide a small sample of the kinds of methods you might use.

The examples just provide a small sample of the kinds of methods you might use.

![]() The nature of the question you ask will often (but not necessarily) determine the nature of the method that lends itself to answering the question.

The nature of the question you ask will often (but not necessarily) determine the nature of the method that lends itself to answering the question.

![]() We have excluded the ‘institutionalisation’ phase which refers to transfer of the learning environment beyond the immediate context of the innovation, since we have presumed that your focus is likely to be on the immediate context only.

We have excluded the ‘institutionalisation’ phase which refers to transfer of the learning environment beyond the immediate context of the innovation, since we have presumed that your focus is likely to be on the immediate context only.

![]() Formative evaluation occurs during analysis, design and development and summative evaluation occurs at the implementation phase (though you might also implement formative evaluation processes while implementation is in progress).

Formative evaluation occurs during analysis, design and development and summative evaluation occurs at the implementation phase (though you might also implement formative evaluation processes while implementation is in progress).

Deciding on the evaluation methods you will use

When you use a pragmatic, mixed-methods approach to evaluation, your decisions about the methods will usually be determined by the purpose of the evaluation, the questions you want answered, and a range of practical issues, including resourcing, as your approach to data collection carries implications for time and, potentially, money. Ideally, a mix of quantitative and qualitative evaluation strategies is best since studying an issue using several different methods which allows triangulation, will strengthen the validity of the conclusions you draw. Considering the kind of data that you require, and the implications for interpretation, will help you to make decisions about qualitative versus quantitative methods, subject to the availability of resources.

Because we are focusing on a pragmatic approach to evaluation that is simple for you to implement, we do not suggest that you need to triangulate at every phase, but only when the purpose of the evaluation demands it. In fact, there are many circumstances where you should not underestimate the value of informal feedback – such as passing a draft to an appropriate colleague and asking for comments, or asking students for informal comments during implementation (and also noting unsolicited feedback). You might also include the results of university evaluations of teaching or subjects, which involves no effort on your part in terms of conducting the evaluation (though they will not give you information you might require during design and development). Another reason that triangulation is not always necessary is that if you are also using a cyclical evaluation approach, rigour is achieved through responsiveness to practice (Schön, 1995) so the process of iteration provides an inbuilt quality control mechanism, as we discussed earlier.

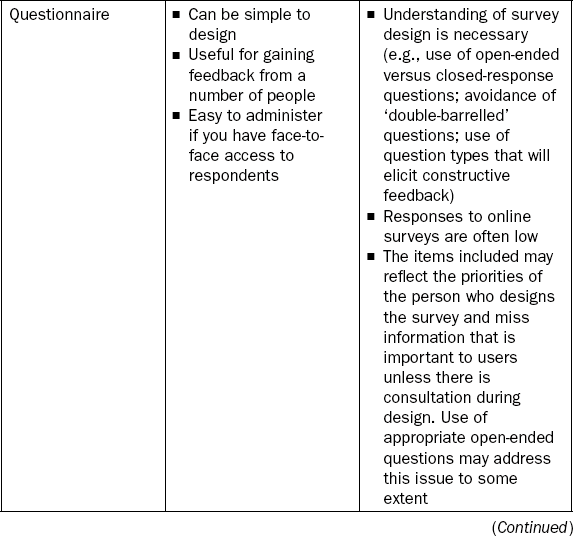

Methods mentioned in Table 5.1 include reviews, interviews, observation, questionnaires, tracking, focus groups and pre/post testing. Reviewing what is already known from the literature and what you know about your students and their learning context is important. You might gain this information from documentation and from talking to colleagues (peers) in your own discipline and in education and technology fields. Once you have some ideas ‘down on paper’ you will want to ask peers and experts to review your plans and give you feedback. This may be through a range of methods including conversation (from informal ‘tea-room chat’ to formal interview), document mark-up, or written comments and is most likely to be qualitative rather than quantitative. The documentation for evaluation may include text, a concept map, a site map or a storyboard. A storyboard is useful if you are planning a complex site where you are working with others on the development. Keep in mind the skills of those from whom you are seeking feedback: remember that an IT expert will be able to comment on the technology but may not have any perspective on the educational design.

By the time you are into the development stage you are likely to have a prototype of your online environment, or part of it, to try out. Here you will branch out and ask some new people for evaluation feedback, and ask about usability as well as design. You will probably first want to know where the key problems are rather than detailed feedback. When you have addressed these problems and you have developed enough of the prototype for a user to be able to complete a unit of work (such as an activity or an assessment task) you may benefit from observing how users go about studying in the environment, which link they go to first, and so on. Combining this approach with an interview or a focus group can give you valuable data from which you can further develop your prototype. When you think you have developed the prototype sufficiently to be usable by students it is wise to ask ‘student-like’ users to trial the environment. Students who have just completed the unit for which you are designing the environment, or postgraduate students, are good choices as they are familiar with the subject and will be able to tell you about gaps and inconsistencies.

At this stage you have a beta version of your environment and you are ready to implement it with your first group of students. This is where you will want to make the most of data collected automatically (e.g., user tracking) and choose methods which will allow you to gather data from a relatively larger number of users, such as questionnaires. Videorecording students in a computer laboratory while they use the environment can be useful for observation.

In Table 5.2 we summarise some advantages and issues to consider in relation to common evaluation methods that you might use.

During implementation, if you have access to a learning management system, you can consider the following options for collecting evaluation data.

![]() Reporting and tracking tools allow you to collect statistics on student activity so you can monitor when, how frequently and for how long students have engaged in or accessed particular parts of the site. This information should be interpreted cautiously: a long time spent on one page may indicate interest, difficulty or a coffee break.

Reporting and tracking tools allow you to collect statistics on student activity so you can monitor when, how frequently and for how long students have engaged in or accessed particular parts of the site. This information should be interpreted cautiously: a long time spent on one page may indicate interest, difficulty or a coffee break.

![]() You can use the online survey tool to evaluate your students’ responses to aspects of your online environment. This allows you to use the same question forms as in quizzes but responses are anonymous. Responses to online surveys often tend to be low so you need to think about ways of increasing the rate of return. Think of strategies that you respond to when asked to complete an evaluation. Reminders and repeated requests using a number of different modes (email, online announcements, text messages, requests in class and personal requests) can be effective to increase the response rate. Explaining what and why you are evaluating, and indicating how you intend to respond to the feedback may encourage responses.

You can use the online survey tool to evaluate your students’ responses to aspects of your online environment. This allows you to use the same question forms as in quizzes but responses are anonymous. Responses to online surveys often tend to be low so you need to think about ways of increasing the rate of return. Think of strategies that you respond to when asked to complete an evaluation. Reminders and repeated requests using a number of different modes (email, online announcements, text messages, requests in class and personal requests) can be effective to increase the response rate. Explaining what and why you are evaluating, and indicating how you intend to respond to the feedback may encourage responses.

![]() You can evaluate a discussion forum by looking at its transcript and by manually quantifying response levels to particular tasks. Although this may be time-consuming, an advantage is that the record of the discussion provides existing documentation for you to interpret.

You can evaluate a discussion forum by looking at its transcript and by manually quantifying response levels to particular tasks. Although this may be time-consuming, an advantage is that the record of the discussion provides existing documentation for you to interpret.

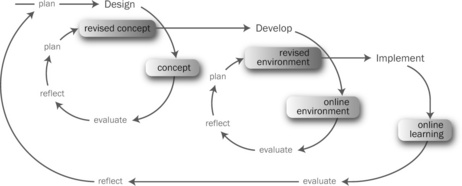

If you use a reflective cycle to ‘process’ the results of whatever methods you use at each evaluation phase, and make decisions which will inform the next phase, then the procedure you will follow is illustrated in Figure 5.2.

Using this approach you may work through each cycle several times, usually with increasingly formal evaluation methods. You may evaluate your design thoroughly before moving on to developing your environment. This way you will limit wasted time developing aspects of a design that are not clearly thought out. However, in reality, you will often work through the cycles bit by bit, designing one small part of your environment, developing a prototype of that one part, then going back to the design phase to refine it in the light of what you have discovered in development. At each stage, different methods for evaluation can be used which may include informal conversation, observation, survey, interview, focus groups and so on, as discussed earlier. Regardless of the method, it is necessary to reflect on the evaluation results and identify what they tell you so you can plan the improvements indicated. At the point of reflection you are looking back at the evaluation, and forward to the next planning stage. You will also have the opportunity to reflect on the evaluation itself and its design, and ask questions about its effectiveness and efficiency at indicating needed improvements.

It is advisable to record your initial plan for all phases in an evaluation plan, which we consider in the next section, because this will keep you ‘on track’ and it may also provide a useful record later for writing up what you did. You can regard this as a ‘living’ document which you change, if necessary, as you modify your plans.

If you are using reflection as a key component of your evaluation it is also worthwhile keeping a reflective log during design, development and implementation as this will increase the value of your data (it is very easy to forget key issues as you move on to address new ones). If you are asking students or others to provide reflections you should ask them to keep a log too.

A final but significant point to emphasise before completing this section is the role of your students in evaluation. If your ultimate goal is to improve the learning experiences of your students, you should consider their role in the evaluation very carefully. This does not mean that you need to supply them with more feedback forms, or that the role of other respondents in an evaluation is not important (the role of other respondents will depend on the purpose of the evaluation). What it does mean is that when you are seeking students’ experiences of your online environment you should ensure, as far as you can, that the focus is really on their experience, and not yours. Not surprisingly, teaching staff regularly design evaluation forms with items that they think are important but it is quite possible that the focus of students’ concerns (both positive and negative) may be on other things. The main point here is that, among the methods you use, make sure that you do address the issue of learner-centredness in your evaluation, though this may involve approaches that are time-consuming from your perspective.

Laurillard’s conversational framework can be used as the basis of an evaluation methodology which allows students’ perceptions to be fully acknowledged, with data obtained during the learning process analysed phenomenographically and then used to prompt and guide students’ explanations during follow-up interviews (Laurillard, 1993).

It is important to recognise, however, that students are often reluctant to participate in evaluations (even offering them a free lunch as an incentive for them to participate in a focus group may not be enough!). This reluctance may be related to repeated requests for their participation in evaluations. To resolve these problems consider your context and circumstances. For example, student representatives who may be on your course management committee are likely to be good sources of information. Otherwise short, informal data collection opportunities may work best. Whatever methods you choose, it is important to close the feedback loop by letting them know what will be/has been done as a result of their feedback so that they can see that their contributions have been valued and their time has not been ‘wasted’.

Taking into consideration the evaluation concepts, methods, and the staged approach to evaluation we have covered so far, in the next section we will look at using this, together with additional information, to design your evaluation plan.

Designing your evaluation plan

In this chapter we are focusing on evaluation of an online learning innovation through the design, development and implementation phases, with the ultimate aim of ensuring that the online learning environment is appropriate for enhancing students’ learning. However, it is important to recognise that evaluation of aspects of the learning and teaching environment can be undertaken for many different purposes, sometimes involving political and funding reasons far removed from the teaching situation itself. Consequently, evaluation can also be undertaken for many different audiences. The concept of stakeholders is important in this. These are the people or bodies with a direct interest in whatever it is you are evaluating. You might think that, in the context of your online development, the only stakeholders would be you and your students. You are certainly the primary stakeholders, but considering the concept more broadly, you would also need to include others in the university responsible for academic or administrative matters or technology support relating to your development, and beyond that to government, and other funding bodies, and so on. This is relevant because when you design your evaluation plan, you need to be very clear about the purpose of your evaluation and the main stakeholders involved.

There are some circumstances when you may need to pay particular attention to including other stakeholders in your evaluation.

If you are undertaking the evaluation as a formal research project, you will also need to seek ethics approval – check the requirements at your institution. Even when the purpose of evaluation is fairly narrowly defined, there are still a number of decisions to be made and questions to be answered about how the evaluation will be conducted, and it is useful to document these.

Reeves and Hedberg (2003) suggest the following components for a (full) evaluation plan:

![]() Introduction (covers the major sections of the plan and the primary people involved in writing it).

Introduction (covers the major sections of the plan and the primary people involved in writing it).

![]() Purposes (includes all purposes of the evaluation).

Purposes (includes all purposes of the evaluation).

![]() Decisions (anticipated decisions to be influenced by the evaluation).

Decisions (anticipated decisions to be influenced by the evaluation).

![]() Questions (the evaluation questions to be addressed – as in Table 5.1).

Questions (the evaluation questions to be addressed – as in Table 5.1).

![]() Method (involves matching options to purposes and questions, and considering budget and timeline).

Method (involves matching options to purposes and questions, and considering budget and timeline).

![]() Sample (includes rationale for sample sizes).

Sample (includes rationale for sample sizes).

![]() Instrumentation (includes all evaluation instruments and tools to be used).

Instrumentation (includes all evaluation instruments and tools to be used).

![]() Limitations (to generalisability and interpretation, including threats to reliability and validity).

Limitations (to generalisability and interpretation, including threats to reliability and validity).

![]() Logistics (outlines who will be responsible for what tasks).

Logistics (outlines who will be responsible for what tasks).

![]() Timeline (for implementation, analysis and reporting).

Timeline (for implementation, analysis and reporting).

![]() Budget (including personnel time, travel, data preparation such as transcribing, etc.).

Budget (including personnel time, travel, data preparation such as transcribing, etc.).

When you are planning a simple evaluation that you will undertake primarily yourself, without expectation of any external audience, we suggest that you should still prepare a modified version that includes the items in the left column of Table 5.3, with a view to answering the questions in the right column.

Table 5.3

Designing a simple evaluation plan

| Component | Questions to ask yourself |

| 1. Purposes | What are the purposes of this evaluation? |

| 2. Decisions | What decisions will be influenced by this evaluation? |

| 3. Questions | What questions do I need to ask to meet the purposes and help me to make the appropriate decisions? |

| 4. Data sources | Who are the respondents who will give me information to answer the questions and/or what sources do I need to consult? |

| 5. Method | What kind of evaluation design is appropriate to the purposes, questions, timeline and resources? |

| 6. Instrumentation | What evaluation instruments (e.g., questionnaire, rating form, focus group/interview protocol) do I need? |

| 7. Timeline | What timeline do I have available for evaluation during design, development and implementation, and analysis at each stage? |

| 8. Resources | What resources do I need and how will I obtain them? |

If you are using a questionnaire as an evaluation instrument it will consist of the questions that respondents will answer and rating scales where relevant. Once you have refined a questionnaire that suits your purpose you may use it as an instrument for evaluating other innovations.

This will keep you on track and, if you are intending to use your own reflections for planning the next cycle of development or implementation, will give you a structured way of collecting the evidence that you will need to draw on to make your decisions. Documenting your evaluation plan, together with results, may also have later, unforeseen, benefits.

We have discussed the first five components in Table 5.3 and alluded to the last three. There are many evaluation instruments available online which may be useful, either as they are or as a basis for an instrument you develop yourself. In Table 5.1 we referred to evaluation at different stages of design, development and implementation. As part of your evaluation plan you will need to build in a time component to allow this to happen, as well as ensuring you have other resources needed such as computer laboratories or video cameras, depending on the methods you have chosen. You may also need to plan and schedule input from others. This may be important in situations where you are ‘too close’ to your innovation to be able to run an unbiased evaluation or when you need an independent evaluator for your student cohort. Both these situations have an impact on reliability and validity. You may also need to involve others if you do not have the time or skills to run all aspects of the evaluation yourself.

Managing, reporting and acting on the evaluation

Managing and reporting

Issues relating to how you will manage and report on your evaluation again depend largely on what your purposes are and the extent to which other stakeholders will be involved. If there are direct implications for audiences other than you and your students, and the evaluation is summative, you (or someone else) will usually also need to prepare a formal evaluation report. Reeves and Hedberg (2003, p. 248) suggest that a typical evaluation report includes:

4. Overview and background (including description of what was evaluated and delineation of the purpose of the evaluation).

5. Decisions (intended to be influenced by the evaluation) and questions (that were addressed).

6. Methodology (including complete description of the design and any instruments that were adapted or developed).

7. Results (possibly organised by methodologies, e.g., interviews, questionnaires, observations, or by the major questions).

Owen (2006, p. 20) summarises the findings of an evaluation as:

![]() evidence (the data collected during the evaluation);

evidence (the data collected during the evaluation);

![]() conclusions (the interpretations or meanings made through analysis);

conclusions (the interpretations or meanings made through analysis);

![]() judgements (in which values are placed on the conclusions); and

judgements (in which values are placed on the conclusions); and

![]() recommendations (the suggested courses of actions in the light of the evidence and conclusions).

recommendations (the suggested courses of actions in the light of the evidence and conclusions).

Notice how the process of decision-making and judgements about worth, which we considered earlier as key evaluation concepts, are reflected in this summary. Nevertheless, Owen goes on to comment that:

What form should an evaluation report take?

The traditional evaluation report is a text-based document, as indicated by the components suggested by Reeves and Hedberg above. However, both they and Owen note the use of less traditional forms of reporting. Owen (2006, p. 126) lists the following types of reports:

In referring to non-written reports, he notes that displays and photography/videos may be used and that displays in the form of graphs and charts can summarise and present large amounts of information in an ‘attractive’ way. He adds that the detail of reporting will vary from evaluation to evaluation and should be negotiated in the planning stage and that generally, a combination of reporting methods is necessary to take into account the needs of different audiences.

These comments are especially relevant for evaluation of online learning environments, and particularly at the design and development stages. Informal reporting may be all that is needed and, because the environment is online, visual reporting that illustrates aspects of the environment and the way that it is used is likely to be highly appropriate.

Acting on the evaluation

Finally, please be aware of the importance of acting on an evaluation. You may wonder why this needs comment if the rationale for undertaking an evaluation is focused on improving the emerging or existing environment to enhance students’ learning. However, you might be surprised at how often evaluations are undertaken, and the recommendations are not acted upon. There might be good reasons for this: for example, you may not have the resources to act, or you may consider that some of the recommendations are not appropriate for your students in their current context. If this is the case, then it is important that you explain this to students if they have provided you with some of the data that has led to these recommendations. These situations are probably very unlikely to occur if you have conducted the evaluation yourself and you are using a reflective process to make decisions and judgements about the next phases of planning but they also serve as a reminder not to include items in an evaluation if you do not intend to act on the responses.

Illustrating the ideas in this chapter …

Suzy continues her story to illustrate how she addressed evaluation of her online environment.

Summary

In this chapter we have covered some evaluation concepts, processes and issues that may be useful as you plan, develop and implement your online environment. We have suggested that valuable concepts include the idea that evaluation involves decisions about the worth of something, using a cyclical, iterative process with reflection as an important component which can form the major strategy for ‘processing’ information from other strategies when making decisions. We have supported a pragmatic, eclectic approach to evaluation, emphasising its importance during design, development and implementation, using simple strategies to encompass both formative and summative evaluation.

We have also emphasised that the purposes of the evaluation should be your starting point, recognising that evaluations can be undertaken for many different purposes and that there is a range of stakeholders who may have an interest in your evaluation. We have suggested that it is worthwhile preparing a simple evaluation plan even if your purposes are quite narrow and you consider that the main stakeholders are you and your students. It is this plan that will identify the evaluation questions you need to ask to meet the purposes, the data sources that will provide the information, the most appropriate methods to use, and the resources you will require. If the purpose of your evaluation is related to the improvement of student learning, make sure that you include strategies that will authentically capture their experiences. Remember, too, that you can include information from other sources (such as university evaluations) as part of your plan. Finally, we have noted some ideas about managing, reporting and acting on your evaluation that we suggest you should consider.

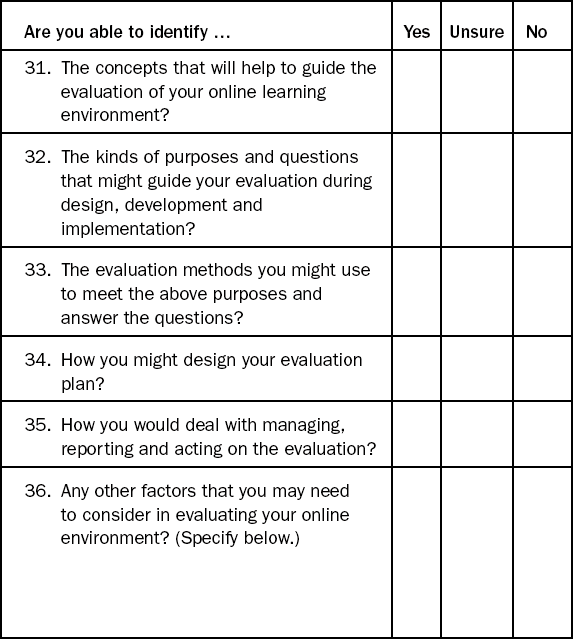

Following we continue the checklist which you began in Chapter 1. The section here covers the aspects of evaluation we have addressed in this chapter. As before, if you are able to answer ‘Yes’ to most questions, you should have a good sense of what is involved, in this case with evaluating your online environment. If your answer to most questions is ‘No’, we suggest that you take the advice we suggested previously in relation to online design, and start with something small and simple. Perhaps try and think of one easy evaluation method that you could implement at each of the stages of design, development and evaluation – keeping in mind that talking to colleagues, talking to students, recording your own reflections, using the LMS tracking system, and so on, all count as evaluation methods in this context.