Online learning design and development

Introduction

The learning objectives which you identified in Chapter 1, and which guided your selection of technologies in Chapter 2, should continue to drive the planning of your online learning design, which we cover in this chapter. They will also guide the design of online assessment, which we will begin to consider in this chapter but address in more detail in Chapter 4.

In Chapter 1, when we asked you to think about how students learn, we referred to two learning theories that have been important in higher education (phenomenography and constructivism) and noted that constructivism has been particularly influential in the field of educational technology. We will begin this chapter with some further comments about theories and models which may be useful in guiding your online learning design. It is the process of designing your online environment which will clarify the need to reconceptualise your teaching which we introduced in Chapter 1.

Then, with your objectives in mind, we will address some important elements of online learning design. These include learning activities (both individual and collaborative, and the provision of feedback on them) as well as the resources and support you will provide for your students. We will refer to both pre-Web 2.0 and Web 2.0 applications in considering these aspects of design.

Following this we will ask you to think about some of the issues you may face in developing your online environment because, along with the issues you considered in Chapter 2, these may also impact on the options available to you. We will then summarise some of the general student support, management and administrative issues that may affect the implementation of your design. By the end of this chapter you should have a good grasp of how to design and implement your online learning environment, prior to considering some specific aspects of online assessment in Chapter 4.

You should keep in mind as you work through this chapter that you do not have to include ‘everything’ in your online environment the first time that you implement it. Online learning design is an iterative process and you will finetune your environment over time as you gain experience and feedback. It is best to start with small, manageable components if you can, rather than trying to do too much and alienating students if they have problems. Such problems experienced early in a teaching period can override the advantages to learning that you hoped your environment would offer.

Theories and models guiding online learning design

Online learning can be regarded as a continuum from classroom- enhanced online learning where the technology is used within the classroom or lecture theatre, through blended learning which involves ‘the thoughtful integration of classroom face-to-face learning experiences with online learning experiences’ (Garrison & Kanuka, 2004, p. 96) to fully online learning. Except for classroom-enhanced online learning, a fundamental difference between face-to-face teaching and teaching online is that there is some degree of separation between learners, and between teacher and learners. A useful way of thinking about this issue, as a first step in reconceptualising your teaching for online learning, is to draw on transactional distance theory (Moore, 2007), which comes from the field of distance education.

Transactional distance theory

The key idea of transactional distance theory is that when there is separation between teachers and learners, you have transactional distance which involves psychological (rather than geographical) distance. This distance is bridged through the appropriate balance of structure (course design) and dialogue, considered in the context of the expected level of learner autonomy and the nature of the particular programme.

Structure and dialogue are usually seen as having an inverse relationship: when structure is high and dialogue is low, you have high transactional distance; when structure is low and dialogue is high, you have low transactional distance. However, Moore (1993) noted that a combination of both high structure and high dialogue can reduce transactional distance. The expected level of learner autonomy will often help to determine the appropriate balance.

We suggest combining high dialogue and high structure for fully online learning, irrespective of learning autonomy, for the following reasons:

… a classroom can support low dialogue and low structure (− D-S) in the online components used because the face-to-face context provides for low transactional distance. However, in contexts characterised by medium transactional distance (such as blended learning environments), an inverse relationship between structure and dialogue is evident, though the specific aspects of the relationship will depend on the context and on the autonomy of the learners. As transactional distance becomes potentially greater in off-campus and transnational units which are wholly or partly online, there appear to be benefits in both high dialogue and high structure (+ D+S) to meet learners’ needs. (Benson & Samarawickrema, 2009, pp. 10–11)

Moore (2004) places his ideas within a constructivist framework, but whether or not you are drawing on constructivist ideas to guide your online learning design, it may be helpful for you to keep dialogue, structure and learner autonomy in mind as you consider the design of specific components of your online environment.

Some online learning models

In addition to theoretical perspectives for conceptualising online learning, a number of specific models have been proposed for guiding design. Whereas theories help to explain how learning occurs, models provide frameworks for implementing these ideas. We will briefly mention four models here. Depending on your objectives, you may find one (or more) of them helps you to conceptualise your online environment. All of them focus on the importance of activity by the learner.

1. Oliver and Herrington (2001) see the online environment as consisting of three major components: activities, resources and supports. Using a constructivist perspective, they recommend beginning with the design of student learning activities. These will be determined by the learning objectives and should involve authentic (‘real world’) tasks. Then design the resources and supports that students will need to complete the activities. Activities, resources and supports are all integrated in the design of assessment. Oliver and Herrington suggest that the most successful forms of assessment occur when the learning tasks and assessment tasks merge, taking the view that clever design of assessment tasks can provide strong supports for learning.

2. ‘Salmon’s (2003) five-step model for teaching and learning online is useful for conceptualising teaching if you are planning to use online discussion groups. This is based on social constructivism. Salmon suggests that teaching and learning using online discussion involves five stages: (1) access and motivation; (2) online socialisation; (3) information exchange; (4) knowledge construction; and (5) development (where participants become responsible for their own learning). The model describes the types of roles you need to play at each stage to get your online discussion activities working effectively.

3. Garrison and Anderson (2003) draw on the collaborative potential of online discussion for creating a learning community to present a community of inquiry model of online teaching and learning. They suggest that within a community of inquiry an educational experience has three primary components: cognitive presence, social presence and teacher presence, and that this framework has potential for structuring, guiding and assessing online learning approaches, strategies and techniques.

4. Laurillard (2002) uses a phenomenographic perspective to suggest that learning is based on the interaction of four characteristics: teacher’s conceptual knowledge, student’s conceptual knowledge, teacher’s constructed world and student’s experiential world. Using a conversational framework, the learning process is seen as a dialogue between teacher and students, involving discursive, adaptive, interactive and reflective components. She uses these characteristics as criteria for judging how learning and teaching systems which use educational technology are best used.

For the purposes of this chapter, it is important to recognise that there are a number of existing models, including those above, which you could explore or adapt to guide your online teaching or assessment. You will find that use of any of these models to guide the planning of your online environment will involve quite a different approach compared to teaching face-to-face. When teaching involves the collaborative activities of groups of learners using Web 2.0 applications, the implications for teaching are even greater and the idea of transactional control, which we outline below, provides a way to conceptualise some of the issues.

Transactional control

For students to take advantage of Web 2.0 applications for learning, you need to consider who will be in control in that environment, the learners or the teacher. Bottom-up control by the group is usually necessary to gain the benefits of group collaboration but you might need to provide considerable support (through dialogue and structure) outside the Web 2.0 environment to nurture the group process, but avoid interfering within it. Dron (2007a) uses the concept of transactional control, which is related to transactional distance theory, to examine the control issues which emerge in the use of social software, suggesting that transactional control is concerned with choices, either by teacher or learners. He notes the potential for learners to generate dialogue through structure and structure through dialogue. Dron explains that transactional control theory ‘does not aim to replace transactional distance theory as it says nothing significant of the psychological gap between learner and teacher, but it helps to explain some of its dynamics’, commenting that ‘[s]tructure equates to teacher control, dialogue to negotiated control, and autonomy to learner control’ (Dron, 2007b, p. 60).

We will now return to your learning objectives which will lead us into addressing some of the key pedagogical components you will need to consider as part of your online learning design. As we do this, we will be referring to the concepts mentioned in this section again so that you can see how they might be helpful in informing your design.

Aligning learning objectives, activities and assessment

A useful design principle that comes from the field of higher education and is informed by constructivist learning theory is that of constructive alignment (Biggs & Tang, 2007). This is the concept that when you design learning, you need to make sure that the objectives, activities and assessments are aligned. This will occur if you design learning activities that will allow students to meet the objectives, and assessment tasks that examine whether the objectives have been met. Although there have been some criticisms of this principle, often because it places definition (and control) of the learning objectives firmly in the hands of the teacher rather than the learner, it is nevertheless a useful concept for guiding online learning design. If your subject requires that students design their own learning objectives, then your objectives can specify this, and they could also specify that students will need to design and align appropriate tasks to allow them to meet these objectives if this is their responsibility.

In each of these examples the activity helps students achieve the objective and the assessment provides evidence of the extent to which they are successful. Keep in mind that the activities you design and/or the assessment may help students to achieve more than one learning objective.

Students will engage more readily when they can see that activities and assessment tasks can help them to achieve multiple learning objectives.

The principle of constructive alignment also sits well with the suggestion by Oliver and Herrington (2001) that successful forms of assessment occur when the learning tasks and assessment tasks merge, providing motivation for students to complete the activities. This means that there will be some overlap between the concepts covered in this chapter and in Chapter 4.

Designing online learning activities, resources and support

If you support the idea of active learning, then the design of the learning activities will be at the heart of your online learning design, providing the means for students to meet the learning objectives, as outlined above. As we mentioned earlier, Oliver and Herrington (2001) see the online environment as consisting of three major components: activities, resources and supports, and they suggest that you begin with the design of your learning activities. This is a simple and intuitive model which we will use to consider these three elements of online learning design.

Activities can take a variety of forms, depending on the nature of the related learning objective, and on the technologies available to you which you considered in Chapter 2. These include interactions of students with each other, with the teacher, with content and with the computer interface through tasks that provide an automated response. In this chapter we will focus particularly on tasks that involve interaction between users, and on those that involve interaction with or creation of content. We will begin in the following section by using asynchronous online discussion to highlight some of the opportunities that communication activities provide and some of the design issues that you need to consider. Activities with automated responses will be addressed in Chapter 4 since these are frequently used in the context of assessment. We include some specific suggestions relating to resources and supports as we consider the learning activities. This will help us apply the model and attend to these three elements of the online learning environment.

This approach should help you to clarify how you might reconceptualise your teaching for online learning because it suggests that the ‘content’ you may have previously presented in your lectures now becomes part of the resources you provide for students to assist them to complete the activities. The affordances of the technologies you have selected will have implications for the design of both activities and resources.

Oliver and Herrington (2001, p. 55) refer to learning supports as ‘the processes and procedures by which learners are assisted in their learning activities, by which feedback and guidance is provided to them and by which their involvement in the learning setting is encouraged and strengthened’. If you draw on transactional distance theory as mentioned earlier, then you could think about the appropriate balance of dialogue and structure (in the context of the expected level of learner autonomy) to help inform the design of the support that you will include.

Interaction between users: online discussion activities

Online communication can be used for a diversity of purposes, ranging from simple socialisation to facilitating high level cognitive and collaborative participation in the completion of learning tasks which are central to assessment. You can craft questions for online discussion relating to learning objectives within each category in Bloom’s taxonomy (The Pennsylvania State University, 2007). This is illustrated in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1

Online discussion questions for different cognitive processes based on Bloom’s (revised) taxonomy

| Cognitive process dimension | Examples of activities | Examples of question types |

| 1. Remember | Recall previously learnt knowledge e.g., Answer a factual question. | Who; What; Where; When; Why; How; Label; State; Recall; etc. |

| 2. Understand | Demonstrate understanding of the meaning of subject material e.g., Explain to a colleague. | Give an example; State in your own words; Demonstrate; Explain; Translate; Classify; Summarise; etc. |

| 3. Apply | Apply subject material to a new situation e.g., Work through a case study. | Predict; Choose the best alternative; Judge the effects of; etc. |

| 4. Analyse | Analyse components or relationships e.g., Review journal articles. | Distinguish; Identify; What assumptions are made?; What motives?; What inconsistencies are present?; What is the main idea or theme?; etc. |

| 5. Evaluate | Demonstrate ability to judge and defend particular issues | Appraise; Judge; Criticise; Defend; Which is more important/moral/accurate/ logical/valid?; etc. |

| 6. Create | Demonstrate ability to develop a new approach in a specific situation e.g., Develop a new creative piece of work. | Create; Develop; Propose an alternative; How would you test?; Plan?; Design?; How else would you do this?; etc. |

If you were using Laurillard’s (2002) conversational framework, designing your discussion groups would provide very clear guidelines for your interactions with students.

Several benefits of online discussion are summarised in Table 3.2. Some of these aspects may help you respond to the characteristics of your students, and the contexts of learning and teaching, that you considered in Chapter 1.

Table 3.2

Some benefits of online discussion

| Aspect | Advantages |

| Students can think, plan and/or reflect before they write. | This may be a particular advantage for students for whom English is a second language, or students who are shy or lacking in confidence. |

| Students express themselves in written form, rather than orally. | This might suit the learning styles of some students, allowing them to participate more easily. |

| Responses to questions are available for all to see. | This minimises the number of similar questions asked of the teacher, and maximises the number of students with access to the response. |

| Off-campus students are supported. | Discussion groups provide feedback on progress, and allow social interaction between the students themselves and with their teachers. |

| Time zone differences are accommodated. | Discussion groups allow interactions between students and teachers when time zone differences prevent easy synchronous communication. |

| Time scheduling differences are accommodated. | Online discussions enable students to communicate at times which suit them. |

Whatever your use of online discussion, students will need guidance on its purpose and how to use it. If you are teaching in a blended environment much of the support you give to students can occur face-to-face. Students can be ‘walked through’ the online environment and expectations can be discussed. When you expect students to engage in discussion online only, you will need to build considerable support into the online environment and orient them to it.

Orienting your students

Once you have planned how you will use your discussion groups, one of the first things you need to think about is how you will communicate this information to your students and provide an opportunity to answer their questions. An orientation session or some prepared orientation information is a very important aspect of the support you need to provide to help students to understand what is being asked of them and why.

It is easy to neglect this important stage and feel pressure to start the ‘real’ work. However, you will usually be rewarded many times over if you handle orientation well, as you will reduce student problems which have an impact on your own time. As we noted earlier, Salmon (2003) suggests that access and motivation followed by online socialisation are the first two steps in teaching using online discussion groups and you should make sure that you allow sufficient time for students to complete these steps.

Access and socialisation

Technical problems related to students accessing online discussions are less frequent now that learning management systems are well established. Nevertheless, you may need to consider issues such as the following.

![]() What computer and network access do your students have?

What computer and network access do your students have?

![]() Do they have access to adequate IT support?

Do they have access to adequate IT support?

![]() What are your students’ IT skills? You may need to consider whether they have used these tools before – for example, a first year or a mature age student may not have encountered the technology.

What are your students’ IT skills? You may need to consider whether they have used these tools before – for example, a first year or a mature age student may not have encountered the technology.

Once you have addressed the technical issues, students may still need some time to become comfortable with your expectations. This will happen more easily if you allow for it as part of the orientation stage. The first step in establishing an online discussion may be achieved with messages of introduction, or about other social matters, or icebreaking activities. This can help foster a sense of community, particularly in classes where students may not meet face-to-face. This step may overlap with discussion topics specifically designed for support. You could ask students to introduce themselves in their first message. You would set the expectation by introducing yourself (thereby providing a model for them). This could be conducted as a separate social discussion topic or be part of a topic associated with a particular activity, depending on the characteristics of the learners, and the nature of the activity. The following example is a suggestion for a first message to introduce students to your expectations.

You could then ask the students to complete an icebreaking activity or you could include this as part of the posting in which they introduce themselves.

Such icebreaking activities may seem trivial but they give you and your students an opportunity to get to know each other and identify as a group, making support easier. They also give students useful connections for supporting themselves such as arranging shared transport (if students live close to each other) or setting up social or study groups (which are often particularly valued by students who are studying off-campus or transnationally).

Online discussion in individual activities

Once you have completed the access and socialisation steps, you can focus on the activities that will help students to meet your specified objectives. Salmon (2002) uses the term ‘e-tivities’ for these learning activities. She considers that each ‘e-tivity’ should have the following key features:

![]() a small piece of information, stimulus or challenge to initiate it (which Salmon calls the ‘spark’);

a small piece of information, stimulus or challenge to initiate it (which Salmon calls the ‘spark’);

![]() online action which includes individual participants posting a response (the ‘invitation’);

online action which includes individual participants posting a response (the ‘invitation’);

![]() an interactive or participative element – such as responding to the postings of others (the ‘action and interaction’);

an interactive or participative element – such as responding to the postings of others (the ‘action and interaction’);

![]() elapsed time allowed and requirements for posting times specified; and

elapsed time allowed and requirements for posting times specified; and

Salmon provides examples of ‘e-tivities’ appropriate for each of the stages of her five stage model (Salmon, 2002). At Stage 3 (information exchange) you would be expecting interaction between students which requires comment on the contributions of others.

However, it is important to set specific boundaries around what you expect students to do. Activities which have too many components may result in students tending to write ‘essays’ online instead of discussion contributions. Encourage students to keep contributions simple, focused and limited in length (no more than one screen of text).

Make sure that your questions or topics do, in fact, lend themselves to discussion. Closed response questions (requiring a ‘Yes’ or No’ answer) do not generate discussion unless you also ask for the reasons for the response. Once one person has posted a response, consider what motivation there is for other students to post. Similarly, avoid questions with factual answers as they leave no room for multiple contributions once one person has answered the question correctly.

Online discussion in group activities

If you are using online discussion specifically to support the idea of students’ learning through collaboration in groups, the concept of a community of inquiry may be helpful in guiding your design. In this context a community of learners forms ‘an essential, core element of an educational experience where higher-order learning is the desired outcome’ (Garrison & Anderson, 2003, p. 22). The success of an online community for learning relies on careful design of activities and supports which give meaning to a collaborative pursuit so students are learning from and with each other rather than alongside each other.

The use of online discussion groups for collaboration can take a number of different forms. The following examples illustrate forms that involve authentic learning tasks. However, note that these are complex activities that require careful planning and organisation. Students need to know exactly what is required of them, and when, which means that you will need to provide a high level of support.

If students are to collaborate effectively on group projects online they need the same teamwork skills as they would need in face-to-face collaboration. These skills of negotiation, decision making, task and time management need time and support to develop. Students are often initially reluctant to collaborate with their peers to produce a shared outcome. They may feel that others are benefiting from their efforts or that a group submission is not of the high standard that they would achieve alone. You may need to provide students with specific support mechanisms for collaborating, and develop a marking scheme which assesses and rewards individual contributions (more about this in Chapter 4). You could include successful teamwork as one of the learning objectives for your students.

When asking students to collaborate online you may have to articulate roles and responsibilities and give them some hints about how to deal with problems that arise. An awareness of the characteristics of your students and your own experience of them should help you to anticipate the difficulties they might have and enable you to prepare them adequately. When in doubt, ask them for their feelings about and experience of collaborating online. In designing the group activity think about how you will allocate students to groups: will you assign them or allow them to self-select (maybe via a sign-up sheet)? Students in friendship groups may use the discussion space you set up for the task for social communication. This may not matter if the online discussion is only used for convenience and flexibility, but if the process of collaboration is also important then a record of it will be required.

You might include in your design for student group work an expectation that students will take the moderating role. If you organise this, it is important that you provide them with guidance about how to undertake it.

The success or otherwise of the activity is likely to be contingent on the level and organisation of the support that you provide.

Supporting online discussion activities

We have mentioned some specific aspects of support in relation to online discussion as we have moved through this section. Moderation of discussion can provide both general and specific support for students. The design of the forum sets up the online environment as a safe place for students where their concerns will be heard, by other students and/or by teaching staff. In this context it is important that you describe to students the level of support you are offering (for instance, when you will be in the online discussion space) and then adhere to this. Off-campus students often find that the availability of other students as part of a learning community is support in itself.

To complete this section, Table 3.3 summarises some common issues encountered in using online discussions with tips on dealing with them.

Table 3.3

Support issues and tips for online discussion

| Issues | Tips |

| Students may be reluctant to demonstrate the limitations of their learning for all to see. | Provide a safe and supportive environment, encouraging all to participate. |

| If the discussion list is used as a record for assessment, then students may be unwilling to take risks in entering into discussion. | Develop appropriate assessment strategies, and stress the importance of participation to your students. Emphasise the relevant assessment criteria. |

| Some students are more comfortable in passive participation (or 'lurking') in discussion lists, just as they are in listening in face-to-face tutorials, rather than actively engaging in discussion. | Does this matter? If not, don't worry! If it does, design appropriate strategies to encourage participation. |

| Students may feel frustrated and negative about participating in online discussions if their comments go unanswered. | Tell your students when you will be online, and encourage fellow students to respond during other times. Make sure that all contributions are acknowledged. |

| Without body language cues, online communication can be misinterpreted. | Act as a role model for your students, e.g., post clear and simple messages, free of jargon or in-jokes. |

Interaction between users: activities using other communication forms

Online chat

You are more likely to use online chat for supporting students undertaking a learning activity, rather than for implementing the activity itself, because of the difficulties in managing these synchronous sessions which we mentioned in Chapter 2. Difficulties include the time constraints of requiring everyone to be present at the same time, and difficulties in pacing text-based responses with replies to one message overlapping new messages and responses to previous messages. However, the sense of immediacy can itself be supportive for some students, giving them a feeling of being ‘heard’.

Online videoconferencing and web conferencing

Videoconferencing is now common for conducting meetings enabling individuals to contribute from remote locations. If you are familiar with this type of meeting you will know that they require greater concentration than a face-to-face meeting. An online videoconference meeting has an additional challenge because the quality of the audio and video is limited by the bandwidth. For an activity where a small number of students collaborate with a clear purpose, online videoconferencing could be motivational.

Managing web conferencing is often easier when one person is presenting to the group. The screen-based presentation lends itself to situations where the presenter has something to demonstrate, but interaction can be increased through activities such as polling and responding to questions from the ‘audience’.

Mobile technologies

Mobile technologies may be an advantage in activities which require flexibility regarding time and place, though the ubiquitous presence of mobile phones means that you may consider uses for them even when there is no separation between you and students in time and place. They allow for immediate, personalised contact which can be either synchronous or asynchronous (as in text messaging) and used for either individual or group communication. If you expect your students to use their own mobile devices (telephones) for class-related activities, you should check first that they are willing to do this. If you then want to build this contact into your teaching, you can use this mode of communication for either providing information to them (such as, assignment advice or results), communicating with each other, or receiving messages from them.

Jones, Edwards and Reid (2009) describe the use of mobile SMS messaging for first year undergraduate students where messaging supported face-to-face teaching and the implementation of student activities on the LMS site. Used in this way, mobile communication can have both a pedagogical and support function. There are other advantages of mobile devices in relation to interaction with and creation of content which we will consider in the following sections.

Tablet computer technologies are useful for engaging students in communicating with the teacher in class. The teacher is then able to share selected contributions with the class as a whole.

Tablet computers have particular benefits in conveying visual information that is difficult to produce quickly via a keyboard and requires specialised software.

Games, simulations and virtual worlds

Games, simulations and virtual worlds offer the promise of activities with rich interaction between users. We have mentioned previously that these environments are an unlikely choice if you are new to online teaching because of their complexity. However, simulated experiences which involve interaction between users (such as role plays) are not complex in terms of the software required (online discussion groups are sufficient), though they can still be complex in terms of design and implementation.

Interaction with content

The online environment, with its abundance of information, offers an excellent opportunity for students to develop research skills. Designing activities which foster students’ abilities to search for, analyse, interpret, critique and summarise information helps them to develop important graduate attributes.

Nearly every activity that you design will require students to interact with content in some way, for learning objectives relating to all cognitive processes in Bloom’s (revised) taxonomy. As we mentioned earlier, this requires you to think about the resources that you will provide and it will often involve reconceptualising the material that you previously provided in lectures as part of these resources.

![]() How much ‘content’ will you provide, through material you develop yourself, readings that you identify and links to other resources? Will you give students all the resources they need or do you want them to develop research skills and find material themselves?

How much ‘content’ will you provide, through material you develop yourself, readings that you identify and links to other resources? Will you give students all the resources they need or do you want them to develop research skills and find material themselves?

![]() What form will the resources take? For material that you develop yourself, your options include text, images, audio or video but how you design these components will be determined by the content and context. Be aware of potential problems with downloading and keep audio and video clips short (usually less than five minutes). If you are designing an authentic learning experience such as a case study or role play, the experience will determine the various (authentic) forms that the resources might take.

What form will the resources take? For material that you develop yourself, your options include text, images, audio or video but how you design these components will be determined by the content and context. Be aware of potential problems with downloading and keep audio and video clips short (usually less than five minutes). If you are designing an authentic learning experience such as a case study or role play, the experience will determine the various (authentic) forms that the resources might take.

How will you provide the resources? Again, for resources that you develop to be used as part of an authentic learning experience, the way you provide them, and the timing of this provision, will be determined by the learning experience.

![]() What guidance will you need to provide for students to interact with content in the ways you require? How will you provide this guidance? This is an important support issue. Remember that tasks as simple as finding information take time and skill and students may need support to do that.

What guidance will you need to provide for students to interact with content in the ways you require? How will you provide this guidance? This is an important support issue. Remember that tasks as simple as finding information take time and skill and students may need support to do that.

The wealth of information online makes it tempting to offer resources as web addresses (URLs). Students can easily become overwhelmed with more information than they can manage if you are giving them all the good sites you have found. For each resource that you consider, ask the question ‘Do the students really need this in order to complete the activity successfully?’ If the answer is ‘No’ but you think the resource is valuable for them you can tag some resources as ‘additional’ or ‘advanced’ and indicate that they are not essential. Annotating resources is also helpful so that students are aware of the content and value of each one. Categorising the resources is essential so that students understand what they are accessing and why. Remember that some resources take time to retrieve and students will lose confidence in them if they find that they are not useful.

When linking online resources to your subject site, consider the copyright implications. It is good practice to explain where the resource comes from.

Remember also that reusable learning objects created by multimedia developers which you can add to your LMS site may be available to provide simulated experiences for your students.

While complex and costly to develop yourself, it may be worthwhile searching to determine whether an appropriate piece of software that might meet your needs is already in existence either within your institution or externally.1

Mobile devices are also increasingly providing opportunities for interaction with content, through their ability to receive information, including visual material captured by others, and their web-browsing capabilities. Their ubiquity extends to places, such as locations in remote areas, where access to the internet may not be available. As always, the students’ characteristics, the learning and teaching context and the learning objectives will determine the best ways of ensuring that students have the opportunities for interacting with content that they need.

Creation of content: individual and group activities

Students undertaking activities that involve creation of content will usually be working at the top level of the cognitive process dimension in Bloom’s taxonomy. You will need to determine the degree of support they will need based on their previous academic experience. Because one of the key affordances of Web 2.0 applications is the ease with which users can create content online, this makes them a good choice for the design of activities where students collaborate in groups to create content.

In this section we will briefly consider the following specific ways that the online learning environment can support creation of content, and some of the design issues involved, through the use of:

Note that the creation of content online, combined with the ready access to existing information online, means that plagiarism can occur very easily. Depending on the academic experience of your students, and the way that you want them to create content, you may need to provide specific advice about plagiarism and how to avoid it. They may need help to distinguish between the use of material or ideas without appropriate acknowledgement and mashups, where co-authored work legitimately combines original content with reuse of internet content from other sources.

E-portfolios

A portfolio is a useful format for collecting evidence of achievements and can form an important basis for preparation for the professions. The portfolio can become a rich assessment item, as well as assisting students to track their own learning. The inclusion of critical reflection extends the portfolio to allow assessment of this valuable graduate attribute.

Mathur and Murray (2006, p. 250) summarise some of the advantages of e-portfolios as follows.

1. Electronic portfolios can be edited, updated, retrieved, and instantly made available to several people simultaneously.

2. Electronic portfolios are user friendly. Voice recordings, digital pictures, and videos by the student, teacher, peers, and other raters can personalize electronic portfolios.

3. Electronic portfolios are designed to accept instant feedback from teachers, peers, and area experts, and provide exceptional flexibility to the process of learning and assessment.

4. Electronic portfolios make it possible to cross-reference a student’s work across content areas. Different parts of the curriculum can be connected and cross-referenced easily.

5. Since it is possible to store, cross-reference, and retrieve student portfolios easily, instructors and administrators can retrieve student work from past semesters and years to display them as examples for future students.

6. Electronic portfolios vividly describe and assess the learning processes and products.

They successfully document learning across curriculum and grade levels.

There are a number of software programs designed for the set up and maintenance of portfolios. In the absence of software with support at an institutional level, blogs provide an excellent vehicle for portfolios. Requiring students to maintain a blog for the semester has potential to address several objectives relating to individual and group learning. We will address other uses of blogs below.

Activities related to e-portfolios need to be supported with training in how to use the technology as well as the usual objectives and guidance on how to achieve the desired outcomes. You will need to liaise with your institution’s technical team to design appropriate initial training on the functionality of the software, but you will also need ongoing technical support as students develop their portfolio and use the technical skills required. While some students may grasp the technology rapidly, others will need further training to use tools beyond the basics as their portfolio develops.

Blogs

As the name implies, a blog (weblog) is an obvious choice for activities that involve journalling and personal reflection. The online environment offers the ability for students to share their work easily with you and/or other students and/or people beyond the classroom, as required, and receive feedback from them. Mathur and Murray (2006, p. 251) summarise some advantages of e-journals.

1. E-journals help in understanding changing contexts of learning and modifying expectations of tasks as needed.

2. Peers, experts, and instructors alike may review the entries and respond to questions and problems. Since it is possible to receive frequent and immediate responses, electronic journal entries often foster relationship building.

3. E-journals are an important way of obtaining multiple perspectives to a problem and eliciting several solutions to a problem.

4. E-journaling is used to brainstorm and reflect on one’s own work and that of others.

5. Online journaling provides a collaborative learning environment that encourages students to question and to resolve difficulties within a social context.

6. Sharing journal entries helps students see how others think and work.

Most school leavers will be familiar with blog technology but mature learners may need support in setting up a blog and understanding access issues. An advantage of blogs is that they are easy to set up and use so you will be able to provide most of the support students need in terms of using the technology.

Reflective practice may be intuitive for some students but others may be unfamiliar with it. You may need to explain what it means, why and how you expect students to engage with it as an activity, and the consequences of their doing so.

Microblogging (such as Twitter) provides a rapid response mechanism allowing multiple entries to be handled efficiently. It is suitable for field work or placement activities, or activities which require students to convey the ‘gist’ of an idea (such as a headline in a journalism subject) and attract the responses of others, but it does not allow for in-depth reflection.

Wikis

The central advantage of wikis, in terms of activities which involve creation of content, is that they provide a collaborative space in which a number of people can create content together. They also offer other advantages which we mentioned in Chapter 2, including a record of individual contributions, the ability to revert to previous versions of the work that is created, and a discussion space that is separate from the ‘work space’.

While wikis are often used in ways that include the teacher’s participation, in student group work they can be used to support the concept of learner control (Dron, 2007b), so that the wiki is ‘owned’ by the group. This may mean, as we noted previously, that you might need to provide considerable support (through dialogue and structure) outside the Web 2.0 environment to nurture the group process, but avoid interfering within it. When the link to the wiki is from a site on the LMS, the support information can be provided on this site. We recognise the conceptual contradiction of entering a user-controlled environment through the teacher-controlled gateway of a learning management system but this offers the advantage of a single access point to the online learning environment and a sense of all the components being part of a cohesive whole. An emerging issue related to student control is that as social software is added to the tools in learning management systems it becomes more difficult to distinguish these spaces as their own.

A useful strategy for supporting students and helping them to prepare for an activity in a wiki is to provide them initially with a simple task to complete in a ‘practice wiki’. This can be important in gaining familiarity with the environment, and particularly in overcoming reluctance to edit each other’s work.

Shared documents

E-portfolios, blogs and wikis are useful if the output of student work is to be a web-based document. However, if the output is to be a text document, a spreadsheet or some other form of presentation that is not web-based, then students working in groups using shared documents such as Google Documents can have the advantage of working on the same document which remains on the server while the task is in progress, and then presenting the final ‘product’ in the format required.

Student podcasting

While lecturers often think of podcasting as something they can do themselves to provide content for their students, learning activities or assessment tasks that involve student podcasting provide an excellent way of engaging them in the creation of content. The video (or audio) format may be particularly suited to activities where students develop skills or put together visual content. Middleton (2009) provides examples of student involvement in the creation of podcasts which include:

![]() nursing staff and students producing video learning objects about clinical techniques; and

nursing staff and students producing video learning objects about clinical techniques; and

![]() journalism students working independently to create vox pops (as an essential journalism technique) with a range of people on the topic of ‘What makes a good student?’, and later creating a short feature on ‘why you would study Journalism at the university’ as a marketing device.

journalism students working independently to create vox pops (as an essential journalism technique) with a range of people on the topic of ‘What makes a good student?’, and later creating a short feature on ‘why you would study Journalism at the university’ as a marketing device.

Thompson (2007) describes a ‘Grammar in a Pod Project’ used in the professional preparation of English language teachers as a means of creating a collective resource for teaching grammar in upper primary school classrooms. The trainees were tasked to create a three minute podcast to explicitly teach a point of grammar and to select a non-fiction text that modelled the use of the grammar point. This was combined with a self-reflection task and a peer review of another trainee’s podcast, thereby combining authentic learning and assessment.

Specific advantages of student podcasting videos mostly relate to accessing authentic content and motivation. The podcast video is easily viewed via a browser by both students and staff, and student control of who has access can be a motivating factor. In the journalism example above, the technology of podcasting is used for real-world communication so both the process and the content contribute to the authenticity of the activity.

Mobile technologies

Just as mobile technologies offer advantages for interaction between users and interaction with content, they also have value in relation to creation of content through their ability to capture and share authentic artefacts. Aubusson, Schuck and Burden (2009) comment on the immediacy and spontaneity of capturing live events, and describe the potential for collaborative reflection that can result from sharing events and deconstructing them with critical friends. This has obvious advantages for some learning contexts and, of course, the mobile device can simply be used for capturing the data with sharing and discussion occurring after it has been downloaded.

Whatever the learning activities you provide for your students, consideration of the feedback that they will receive when they complete them is a design issue that is of critical importance for both guiding learning and offering support. Often the nature of the technology you are using will determine how this is done and its affordances will streamline the feedback process. In the following section we address some of the aspects of feedback that you should consider.

Giving activity feedback: principles, options and issues

Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006, p. 205) suggest seven principles of good feedback practice, indicating that it:

1. helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards);

2. facilitates the development of self-assessment (reflection) in learning;

3. delivers high quality information to students about their learning;

4. encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning;

5. encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem;

6. provides opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance;

7. provides information to teachers that can be used to help shape teaching.

Feedback will usually be formalised when it occurs in conjunction with graded assessment tasks (which may be relevant if the learning activities that you design contribute directly to this assessment). However, ideally there will be plentiful opportunities for informal feedback prior to this and it is important that you make students aware that it can be provided in a variety of ways. Explain how they will be receiving feedback so that they recognise it as such. Emphasising the role of feedback from sources other than you can both reduce your own workload and provide direct benefits to learning. For example, Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick present their principles in the context of helping students to take control of their own learning and becoming self regulated learners by generating their own feedback. In addition, online communication can be valuable for supporting peer feedback. This has benefits for the student providing the feedback through the critical reflection involved, as well as for the student receiving the feedback who might then respond, and for others who observe or then build on the feedback that is generated. When students are working in groups, feedback to each other becomes a natural part of their engagement and learning as they work on a task together. Nevertheless, students often like to hear (virtually or otherwise) the voice of the teacher as well. Whatever you decide, make sure that you let students know exactly what to expect.

Encouraging students to give and seek feedback can help them to become independent learners. Suggest sources of feedback to them. As well as each other, this could include family and friends (many of us would encourage students to get a friend to read an essay before submission), colleagues in their workplace or mentors both personal and professional. Often workplace supervision of students on vocational placements will be built into their study programme and it is important that they recognise that the feedback they receive from these supervisors and others in the workplace plays a vital role in their learning.

As for feedback that is provided in a formal assessment context, activity feedback should be timely, informative and supportive.

Timely feedback

A key benefit of the online environment for feedback is the ability to speed up its provision – this is instantaneous in the case of automated feedback which we will consider in Chapter 4. For other forms of feedback, make sure that your subject structure allows for and encourages the provision of prompt feedback. This may involve clearly communicating expectations to those who are providing feedback, which may include the students themselves. In cases where your own workload or that of others may delay feedback, make sure that this period is minimised and that you let students know when feedback can be expected.

Informative feedback

As the principles suggested by Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) indicate, feedback should convey specific information that is directed towards improvement of learning. Thus, any judgement (even ‘Well done!’) should refer to the reasons supporting the statement. When tasks are not well done, specific suggestions for improvement should be included.

Supportive feedback

The supportive role of feedback is also covered in Nicol and Macfarlane- Dick’s principles (no. 5). In an online environment this is especially important because the isolation resulting from the separation between teacher and other students can cause considerable anxiety for students and the need for higher levels of reassurance than you might usually provide.

Developing your design

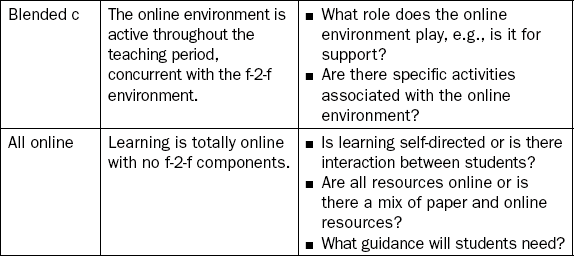

Once you have a clear idea of the kind of activities, resources and supports that you want to include in your online environment, you will need to think about how you will integrate them in that environment. How you do this will be determined to a large extent by whether you are planning a classroom-enhanced environment, a blended one of the type a, b or c in Figure 3.1, a completely online environment, or a variation of one of these.

Not only will you need to integrate activities, resources and supports, but also integrate modes of learning so that the online learning relates to the face-to-face learning (where applicable) and all relates to assessment, making sure students know where resources and support are, and when, where and how to access them.

Each of the types of learning environments shown in Figure 3.1 has its own issues in relation to development and implementation. A totally online environment with no opportunity to resolve difficulties face-to-face is often the most challenging. Table 3.4 covers some of the development issues related to each of these options.

Now you can start planning the overall structure. Think about the following questions.

![]() What support will you need? You may need to have technical training, e.g., in the use of the LMS. Or you may need an expert developer, e.g., a web developer, multimedia or video developer. If you need to involve a developer you will probably need funding.

What support will you need? You may need to have technical training, e.g., in the use of the LMS. Or you may need an expert developer, e.g., a web developer, multimedia or video developer. If you need to involve a developer you will probably need funding.

![]() Will you need to involve other teachers? If you teach with tutors you may need to involve them in the planning and implementation to ensure that the roles they undertake support your design.

Will you need to involve other teachers? If you teach with tutors you may need to involve them in the planning and implementation to ensure that the roles they undertake support your design.

![]() What timeframe will you need to consider? If you are planning a big project you might decide to incorporate a number of phases with trials, formalised evaluation procedures, and contingency planning.

What timeframe will you need to consider? If you are planning a big project you might decide to incorporate a number of phases with trials, formalised evaluation procedures, and contingency planning.

There are a number of issues which may affect your planning. We have touched on some of them already but Table 3.5 provides a summary list for you to consider.

General student support issues

We have covered a number of issues and opportunities involving support in relation to learning activities throughout this chapter because the design of support for students is an intrinsic component of online learning design. We have also referred to support in guiding students to resources to encourage appropriate interaction with content. The guidance on how to go about an activity, training in the use of technologies, and instructions required to complete it are all part of the support that you provide.

Think back to the characteristics of your students and the context of their learning and this will provide you with clues about the support facilities that you should provide as part of the design of your site. Once you have done this, the advantage of your site as a dynamic, living space, means that you can tailor more specific forms of support as you go along. Remember that if you are using transactional distance theory to guide your design, your use of dialogue and structure may be key components in planning the supports that you will provide.

As well as support that is specifically shaped to help students complete particular kinds of activities, at a more general level you will support students in knowing what to do and what is expected of them, and what they can expect from you, through different forms of guidance, announcements, schedules, etc. If you find that students often ask the same questions, you may need to compile some ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ to provide them with answers. Yet another level of support is usually provided at an institutional level and students may need to be reminded of this.

Any particular cohort of learners might also need specific support related to their circumstances. The characteristics of your students which we explored in Chapter 1 will help identify these needs.

As part of this you will also need to consider their requirements in terms of technical support which we addressed in Chapter 2, building it in to your design as we discussed in relation to online communication earlier in this chapter. However, take care to avoid stereotyping (as we also mentioned in Chapter 2) and focus on the particular characteristics of your students that you have identified. Choosing a mode of communication with your students that is readily available, or with which they are familiar, has accessibility advantages. Mobile devices can be useful in this regard. As always, this will depend on the characteristics of your students.

Many students are familiar with text messaging and may support each other in this way, whether or not you are involved. In deciding about your involvement think carefully about how integral this is to the learning experience. If you encourage students to contact you for support, will they develop an over reliance on you and under utilise the resources and support in their placement environment? Or will your support be a lifeline for students in unfamiliar and unsupportive environments? You will need to consider the workload both for you and for students if you build mobile communication into support arrangements.

Managing and administering online learning

You will have been aware as we considered the design of different kinds of activities and resources, that the management of these components may have major implications for your workload, both in setting up your online environment and then in running it. A considerable proportion of this will involve management of the aspects of support that we have discussed.

Managing discussion moderation

When you are running activities through online discussion the role of e-moderation in ‘chairing’ or managing the discussion in ways that will guide learning can be very time consuming if you don’t plan it carefully. This is usually the role of the teacher or tutor but, as we discussed earlier, it can also be a valuable role for students to play (on an allocated basis) which will help them focus on shaping a particular discussion to meet the learning objectives for which it was designed.

As we also indicated earlier in this chapter, the initial goal of e-moderation is to welcome and encourage students, and to facilitate socialisation in establishing a learning environment. We noted in Chapter 2 that online discussion rarely occurs spontaneously. There are many examples of teaching staff providing discussion forums which students never use. The success of an un-moderated discussion depends on its purpose and the characteristics of participants. You can influence the outcome of the discussion by knowing the characteristics of your students and what motivates them. The socialisation stage is a good time to find out more about your students. Ultimately, you will need to weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of providing an un-moderated discussion topic. Often this will depend on whether you are providing the discussion space primarily for learning activities, support or social purposes.

Managing time

One of the major concerns that staff often have about teaching online is the time involved. Online activities which require feedback to individual students from you will require commitment of time, whether it is an activity based on a quiz format, a discussion, or a web editing application (e.g., blog or wiki). The timing of the workload depends on the application. For example, designing a quiz with feedback on each alternative question response requires an upfront investment of time, whereas the timing of feedback for discussion or collaborative activities will depend upon when students are completing them. Working in the online environment can easily take much more time than you realise or intend, so you may need to develop strategies to accommodate this. For example, set aside certain time periods each week for your online teaching, or try to complete most of the development work outside teaching periods (easier said than done!).

In managing online discussions there are a number of strategies that can help you to manage your time.

Your students will also face some time-related issues which you need to manage.

Many of these considerations apply equally to any online activity where students make contributions. Students creating e-portfolios, blogs or wikis may want individual feedback on their work to ensure they are on the ‘right track’ before proceeding further.

Managing expectations

Managing student expectations is another important aspect of teaching online.

![]() Be clear what you expect from your students: What are you hoping your students will gain from engaging in a particular activity? Is it necessary that they all actively participate? In a discussion activity, are you going to allow students to just read postings from others (‘lurking’)? It may be that reading all postings will achieve the same learning outcomes for shy students, as active participation in the discussion will achieve for more outgoing students. The resolution of this issue will depend on the purpose of the discussion in relation to learning and assessment.

Be clear what you expect from your students: What are you hoping your students will gain from engaging in a particular activity? Is it necessary that they all actively participate? In a discussion activity, are you going to allow students to just read postings from others (‘lurking’)? It may be that reading all postings will achieve the same learning outcomes for shy students, as active participation in the discussion will achieve for more outgoing students. The resolution of this issue will depend on the purpose of the discussion in relation to learning and assessment.

Do you require all online engagement to be related to the unit content, or will you allow students to communicate with each other on other topics?

You may like to provide areas where students can post messages about difficulties with technology, particularly if they are becoming distressed or frustrated with accessing parts of the unit. Students may not always articulate their distress about technology, and may feel that they are the only ones suffering a particular problem.

![]() Be clear what your students can expect from you: Are you going to respond to all questions within a specified time frame? Are you simply going to monitor all student activities, and correct only any misinformation that is posted? Or are you going to refrain from responding for a specified period, and encourage others to respond?

Be clear what your students can expect from you: Are you going to respond to all questions within a specified time frame? Are you simply going to monitor all student activities, and correct only any misinformation that is posted? Or are you going to refrain from responding for a specified period, and encourage others to respond?

Students often complete their online work late at night or at weekends, so providing prompt feedback is obviously unrealistic (but some may still expect it!). You might give an undertaking to answer questions or provide feedback within two or three working days.

If you prefer to encourage students to answer questions posted by their peers, you will need to make this expectation clear. Perhaps you could commit to providing feedback after seven days, to allow sufficient time for students to read the question, and undertake some research if necessary. Maybe a ‘reward’ could be offered for the best student answer.

![]() Set clear rules and standards for discussion postings: A basic expectation you may need to communicate to students is the style and standard of their online contributions. If the purpose of communication is peer support, informal language may be appropriate, but for communication associated with learning activities a more formal style may be needed. However, it is important not to expect students to write ‘essays’ in discussion spaces – the style of communication needs to fit the medium and the characteristics of the tool. While online discussions are text-based, they have many of the characteristics of verbal communication. Online communications cannot take advantage of facial and bodily cues, so using an appropriate ‘tone of voice’ in messages is important.

Set clear rules and standards for discussion postings: A basic expectation you may need to communicate to students is the style and standard of their online contributions. If the purpose of communication is peer support, informal language may be appropriate, but for communication associated with learning activities a more formal style may be needed. However, it is important not to expect students to write ‘essays’ in discussion spaces – the style of communication needs to fit the medium and the characteristics of the tool. While online discussions are text-based, they have many of the characteristics of verbal communication. Online communications cannot take advantage of facial and bodily cues, so using an appropriate ‘tone of voice’ in messages is important.

Depending upon your students’ experience of learning in the online environment, you may need to specify some basic rules of netiquette.

Managing large groups

If you have a large cohort of students, you will usually need to divide them into groups to manage online activities effectively. This raises the question of how you manage each group. While the ‘global’ response mentioned earlier is one option (and this could be offered in a general discussion space which is open to all), it will often be more beneficial in terms of feedback to students if you (or someone else) can be responsible for managing students at the group level.

Managing difficult situations

Smooth running of an online class requires good communication skills both written and oral, including ‘listening’. Despite good intentions, difficult situations can arise in handling students with poor communication skills. Maintaining boundaries is central to dealing with these situations.

Recognising poor communication behaviour early can help keep a student (or a group of students) on track. Poor communication skills can also result in silence, and this is difficult to distinguish from those who are ‘lurking’ in online discussion. It may mean that students are having problems, or that they are reluctant to communicate either in a ‘public’ discussion space or privately with you, or there may be some other reason.

If the activities are well aligned with the objectives and assessment, the problem of non-participation should not occur, particularly if the activities form part of the assessment. However, you may still need to provide support to guide students in participating appropriately.

Illustrating the ideas in this chapter …

On the following pages, Suzy continues her story to illustrate how she addressed aspects of online design and development.

Summary

This chapter has covered some of the key issues that you will need to consider as you begin to design your online learning environment. It has introduced some additional theories and models that might help to guide your design. We have addressed the alignment of learning objectives, activities and assessment, noting the value of merging learning activities and assessment, and of using activities as the starting point of your design, to help students meet the relevant objectives. We have focused particularly on activities that involve communication and/or collaboration among users, and those that involve interaction with or creation of content, in each case highlighting the importance of designing appropriate resources and supports to assist students in the completion of the activities. We then noted some of the issues that you might need to consider in developing your design, and commented on general student support, management and administrative issues that may be relevant in implementing it. We hope you now recognise the extent to which you will need to reconceptualise your face-to-face teaching or assessment practices in the online environment.

Design and development for teaching in an online environment can be quite challenging when you do it for the first time so we would again encourage you to start with something small and simple, if possible. You should regard this as an iterative process that will evolve as you gain experience of teaching or assessing online, drawing on the feedback that you receive. It is also advisable to evaluate progressively during design and development as this will guide you even before you have offered your online environment for the first time. We will consider some strategies for doing this in Chapter 5. You will develop numerous ideas for adjusting your design from your first experience of online teaching, both through formal evaluation processes and the experience itself. This will help you to finetune aspects of the environment to achieve a better fit with your students’ characteristics and your learning and teaching context. It may also alert you to support, management and administrative issues that you will need to address (and, in fact, found you had to address during the first iteration) but did not initially consider.

In Chapter 4 we will focus specifically on online assessment design and implementation which, as we have said previously, will involve some overlap with this chapter because of the links between objectives, activities and assessment.

The checklist which you began in Chapters 1 and 2 continues below. It covers the aspects of design and development we have addressed in this chapter. If you are able to answer ‘Yes’ to most questions here, you should have a good initial sense of what is involved in online design, development and implementation even though you are likely to refine those ideas later. If your answer to most questions is ‘No’ it may be helpful to try and locate as many examples of online learning design as you can (within your institution or beyond), especially designs that are helping students to meet the kinds of learning objectives that you have in mind. Seek out sources of academic professional development if you have not done so before and try to identify successful online teachers. Talk to them, find out what they do, and get their advice on the opportunities and challenges. And remember to start with a small and simple online component if you possibly can.