Teaching with technology – considering your options

Introduction

The technology options that are appropriate to meet your needs and those of your students will be determined largely by the factors you considered in Chapter 1, even though most of them may have appeared to have little to do with technology. With these factors in mind, in this chapter we will work through some of the main issues that you need to consider in identifying your options, with a view to making a final decision about the technologies that will meet your needs by the end of the chapter.

We will begin with your learning objectives. As we have already suggested in Chapter 1, these play an important role in the selection of technologies because what your students need to do to meet the objectives has to be matched with technologies that offer the functionalities you require. If you are planning to use technology infrastructure provided by your institution (which we have suggested is advisable if you are new to online teaching in order to ensure institutional support), this is another key issue that you will need to think about which may influence your options.

We will consider the above two issues before focusing on the technologies themselves and outlining some of the main online tools that are currently being used for learning and assessment. We will then briefly address what the future might hold. What you are able to select from these options will also be determined by further student support, management and administrative issues. We will cover some of these additional issues. They are likely to narrow your options even further.

Once you have made all these decisions, it should be fairly clear what your technology options are. How you use them will then be determined by the design and development decisions you make which we address in Chapter 3. This will involve the idea of reconceptualising your teaching which we introduced in Chapter 1.

Technology affordances and learning outcomes

Laurillard (2002) popularised the use of the term affordances in relation to educational technology to describe the support for various kinds of learning experiences which are offered by different kinds of media. Bates (2005) provides a useful distinction between the terms media and technology. He suggests that a medium is a generic form of communication associated with particular ways of representing knowledge, and that each medium may use several different delivery technologies. What this means if educational technology is to be used, is that an intended learning outcome, as specified by a learning objective, will require the selection of a medium and technology with the properties that will allow that objective to be met.

Laurillard (2002, p. 90) identified five media forms, relating them to examples of methods or technologies used to deliver them and the kinds of learning experiences that they support. In Table 2.1 we have updated her explanation to include examples of Web 2.0 applications which are now available to extend learning experiences relating to all media forms. (Note that Laurillard uses the term ‘interactive’ to refer to interaction with presentational media where users can navigate and select content. Later we use it more broadly to refer to relationships between users, as well as between users and content, and users and the computer interface.)

Table 2.1

Five principal media forms with the learning experiences they support and some examples of methods used to deliver them

Source: Adapted from Laurillard, 2002, p. 90.

The implications of this approach are that you should examine the kinds of learning experiences students will need to have, based on the learning objectives that you have identified, and then select technologies within an appropriate media form that will allow students to have these experiences and meet the objectives.

One of the issues you will need to think about when you consider technology affordances and learning outcomes is that narrative technologies offer passive, rather than active, learning experiences. However, they can certainly be used to trigger active learning. Alternatively, the use of narrative technologies by students to generate content themselves can provide a valuable active learning experience for them that could form part of their assessment. Web 2.0 applications, in particular, lend themselves to this due to their facility for the creation of content online.

Now that you have an idea of how the learning objectives begin to shape your choices of the technologies that will be appropriate for you to use, we will consider how the policies and infrastructure of your institution may further influence your choices.

Institutional policy and infrastructure

There is usually a time lag between the availability of new technologies and their uptake by universities (Barnes & Tynan, 2007). The technology infrastructure offered by your institution for teaching and learning will encompass technologies available for your use which have achieved a state of ‘sustainable embedding’ (Nichols, 2008). It is generally best to use these technologies if you are new to online teaching because, not only will there be support in cases of technology failure, it is also likely that your institution will offer associated professional development for staff, as well as support for students. In addition, software that links the technology to your institution’s student administration system means that your students can log in without difficulty, and security and privacy issues are also addressed: you are not exposing students’ details and contributions to a private provider or an environment available to the public. A further important aspect is that if you are primarily interested in issues of learning and teaching and, in relation to technology are not necessarily an ‘innovator’ or ‘early adopter’ (Rogers, 2003), this allows you to focus on the pedagogy and avoid the frustrations of dealing with technology breakdowns, or administrative tasks such as manually enrolling students into non-institutional systems. Your institution may have policies on these matters that limit or preclude the use of external software or providers.

If a state of sustainability in relation to particular learning and teaching technologies has been achieved by your institution, a number of prior processes will have occurred. It will mean that formal strategic planning by your institution has encompassed adoption of these technologies, informed by appropriate academic leadership. This will have led to the implementation of institutional policies related to the technologies, and accompanying standards, systems and procedures. Your institution’s central information technology service will have taken responsibility for implementation of appropriate hardware and software, including backup and support procedures. The decision-making and costs involved in ensuring appropriate institutional provision contribute to the time lag mentioned above. This is often related to ensuring that particular technological innovations have matured sufficiently so that the advantages to learning and teaching are clear and warrant the investment involved. Many institutions have adopted proprietary learning management systems/virtual learning environments (LMSs/VLEs)1 to provide an aspect of infrastructure and a set of tools designed for online teaching and learning. These systems are continually evolving, although they are also characterised by the same institutional time lag in the incorporation of new technologies.

While using your institution’s chosen platform will limit your technology choices and your ability to take advantage of cutting-edge innovations in technologies, it will also mean that you are likely to be introducing online teaching or assessment approaches in a secure environment where advantages to learning have already been established. There are usually still plenty of innovative opportunities that you could explore in the ways that these technologies might be used. Use of your institutional system will not preclude you from incorporating innovations beyond the system in the future.

Keep the issues that we have just considered in mind as we now provide an overview of some of the technologies available for learning and assessment. Focus on those that appear to be most relevant for you based on your learning objectives and institutional context. We will then ask you to consider some further student support, management and administrative issues towards the end of the chapter.

The evolution of internet technologies for learning and assessment

Tim Berners-Lee began development of the World Wide Web in 1989 but it was not until the Mosaic web browser became available in 1993 that the internet became widely accessible (Richardson, 2009). The development of Web 2.0 applications followed the dot-com collapse in 2001: before this the web was characterised by static, non-interactive websites and proprietary rather than open source applications (O’Reilly, 2005). Nevertheless, the social potential of the online environment for education was being explored prior to, and in parallel with, these developments, with an acceleration in the use of computer mediated communication in the 1980s (e.g., Mason & Kaye, 1989) reflecting the evolution of social software which Allen (2004) suggests began in the 1940s.

In this and the following sections, we will consider the affordances of various technologies in three main categories: those that allow interaction between users; those that involve interaction with content; and a third subsequent category which combines aspects of the other two, accommodating interaction between users and with content, allowing creation of content by users. We also add a fourth category for other forms of interaction not included above.

Following the development of the World Wide Web, the major coordinated development that supported both interactive and content-based options for online learning and assessment in higher education was the emergence of proprietary learning management systems as mentioned earlier. These systems brought together a range of tools that teachers could select from, manage themselves and use within a single online learning environment. They are prevalent in universities around the world and new tools continue to be developed for them, or to be available as ‘plug-ins’, though there is now also considerable competition from open source systems. It is quite possible that when you select your technology options, you might be choosing from the tools available within your institution’s learning management system.

The most recent developments within the World Wide Web have followed the advent of Web 2.0 applications. Web 2.0 refers to the different ways that software developers use the web rather than to any change in technical specifications. The significant differences relate to ways that information is shared, the interoperability of software, and the ways in which communication is set up, with the term ‘social software’ used to describe applications which facilitate online communities. Before venturing into using these for teaching and learning it is wise to understand how ‘first generation’ internet technologies, which are part of these new options, work.

The term ‘first generation’ in relation to technologies refers to fundamental capacities of the internet which allow interaction between users and with content. We will consider these at a basic level before exploring the ways in which new technologies, including social software, use and extend them.

Choosing your technologies is a first step in planning your online learning environment once your pedagogical requirements have been identified. In the next two sections we will look at some first generation technologies that you might consider for online learning or assessment. In Chapter 3 we will address some important design issues to consider once you have chosen your technologies.

We will consider interactive options first because these are directly related to active learning. Interactivity in relation to computer based applications has been interpreted in many ways. In the context of online learning, Sims (1999) refers to interactivity as a form of human-computer dialogue, where the user initiates action and the computer responds. Sims includes in this description computer feedback to a learner response (which he refers to as adaptation), participation with the computer software as in a ‘game’, and communication with other users. We will include options that allow interaction between users, between user and content, and between user and the interface. We will begin with interaction between users. If your objectives require communication, this is usually one of the easiest ways to introduce online interaction.

First generation internet technologies: options for interaction

Interaction between users

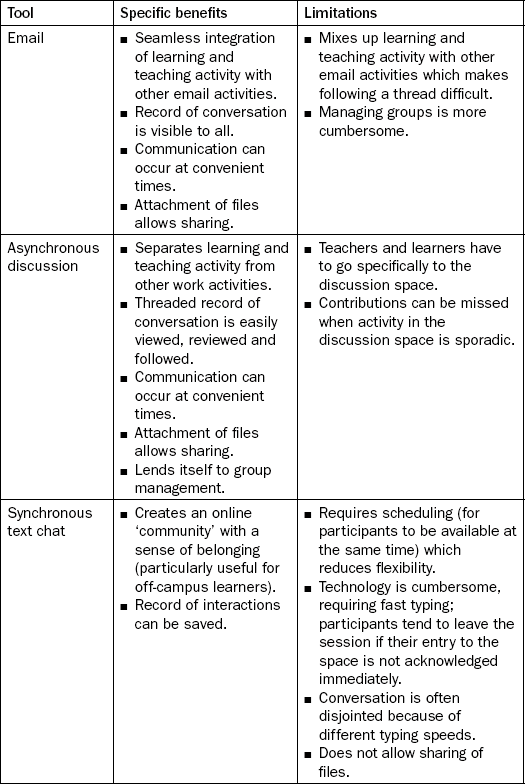

Common online communication tools used in higher education for interaction between users include email, asynchronous discussion and text-based (synchronous) chat. Email is the most common form of asynchronous online communication. It can be used to support one-to-one or one-to-many interaction, and also to convey information in the body of the message (including links to websites) or via attachments. In the context of online learning and assessment it is particularly valuable for private communication but is cumbersome for communication between groups, which is where asynchronous discussion groups (or bulletin boards) offer advantages. These can be used for individual communication within a group and for a range of group activities, including debates, case-based learning, role plays, and project-based collaboration. We will consider some of these options in Chapter 3. The ability to ‘thread’ messages on the same topic is an important organising feature. They can also be used for support and community building and for access to ‘guest lecturers’ and other experts, as well as to you. Alternatively, synchronous text-based online chat offers the advantages of real-time communication and this can contribute significantly to a sense of identity and the building of an online community.

These forms of communication have benefits for teaching but they also have limitations, an awareness of which will help you to choose your tools wisely. While asynchronicity places management of communication in the hands of the receiver, thereby enhancing the flexibility of online learning, the time delay can be frustrating for a sender who is hoping for an immediate response (such as a student requiring clarification in order to complete a learning activity). Online chat allows real-time communication but requires everyone to be available at the time specified and can be cumbersome to manage as the conversation is often disjointed as comments are keyed in and posted. Nevertheless, for those who are available to participate, online chat provides an important point of contact. Transcripts of a conversation can be circulated for the benefit of those who could not take part. Table 2.2 summarises some of the benefits and limitations of email, asynchronous discussion and synchronous chat.

The value of these tools for learning or assessment is dependent on the ways in which they are used. Students don’t discuss spontaneously; they need explicit tasks and support. This can be given via the discussion itself or can be built into the surrounding environment as illustrated in Figure 2.1 which provides an example of how online discussion can be used for case-based learning.

Figure 2.2 shows a chat session within an LMS, indicating the layout (interface design) and the nature of the text space.

We will explore issues relating to online design for interaction between users in Chapter 3.

Interaction with content

One of the main advantages that web-based resources offer over linear, narrative technologies such as video and audio is the ability to navigate, search for and select content. This may allow students to meet objectives that require exploration of resources but it may not be sufficient to guarantee effective learning.

Students may need to be supported in developing academic literacy by exploring the differences in ways of searching for information.

Other forms of interaction

Other common forms of interaction include quizzes and surveys, and multimedia interactions that may be designed to include automatic feedback. There are many tools readily available for the former (for example, within an LMS) but the development of multimedia interactions is usually costly, involving the skills of a multimedia developer and a complex design and development process. During the 1990s the proliferation of software programs resulted in many multimedia ‘packages’ which created interactive environments for self-directed offline learning. These programs use media which are external to the tools of an LMS but they can be used as components within it (embedded) or linked. They can also be used within Web 2.0 environments such as wikis or blogs.

Figure 2.3 illustrates an online quiz using a tool within an LMS to help students meet knowledge-based objectives.

Figure 2.4 also illustrates a quiz which is designed to help students meet a knowledge-based objective, using a multimedia interaction rather than an LMS quiz tool. This provides more flexibility in the way that an item, and the feedback on it, can be presented but it requires the specialist technical skills of a multimedia developer to prepare. An activity may be constructed entirely in a multimedia format, or may be a hybrid of multimedia and html (the language used for web pages). The advantage of the latter is that the html component is easily modified over time. Elements constructed by multimedia developers are usually exported in formats viewable in a web browser but are not themselves editable. Any change to the activity requires further input from the developer. While these are often still relevant they are limited by their inflexibility when it comes to amending them. If specialised technical skills are required you may need to explore funding options before you start development and you would need to allow additional time. For your first experience of setting up an online learning environment it is probably best to focus on learning objectives that students will be able to meet using tools that are already available which you can set up yourself (with some support, if necessary).

In Figure 2.4, the multimedia software allows the consequences of the student decision to be explored in an animation which gives feedback to reinforce learning.

First generation internet technologies: options for managing content

If your objectives indicate that you need to prepare content for your students so that they can complete a task, you have a number of choices of the format you might use in an online environment. These choices include: text (e.g., Word document, pdf, html), presentation software (e.g., PowerPoint), audio, video, animation (e.g., Flash), images and graphics (e.g., gif, png, jpg), etc. The choice of media and the design of the content depend on the objective of presenting it to students. We will explore here some of the issues involved in presenting content in different ways.

![]() Text-based content: Whether or not you need to develop text-based content for your online sites will depend on your target audience and their access to libraries or other resources. Often adding vast amounts of content online is not the most efficient way for students to learn (how many of us still prefer to print out material to read?). If your students have easy access to printed material such as printed study guides, textbooks and journal articles, then you don’t need to add this online. Instead, you can focus on developing content that is best provided via electronic media, for example, animations, audio or video segments.

Text-based content: Whether or not you need to develop text-based content for your online sites will depend on your target audience and their access to libraries or other resources. Often adding vast amounts of content online is not the most efficient way for students to learn (how many of us still prefer to print out material to read?). If your students have easy access to printed material such as printed study guides, textbooks and journal articles, then you don’t need to add this online. Instead, you can focus on developing content that is best provided via electronic media, for example, animations, audio or video segments.

If you do add content as text to your online site, writing for online delivery is quite different from writing for print. For instance, good online writing is often less formally structured, and includes fewer words but more explanation.

![]() Visual content: The online environment allows you to communicate content in other ways so that you can capitalise on the features of the electronic medium and address different learning styles. For instance, visual learners will benefit from content interpreted visually. Images, graphics, animation and video can, in some cases, communicate an idea or concept more efficiently than words. This is evident in documentaries such as Walking with Dinosaurs. Here, not only the viewers were enlightened but the scientists also found they learned an enormous amount from having to visualise beings and events. Video and images can communicate context which is not immediately available to the learner. Obviously, video is a good choice for film and theatre studies.

Visual content: The online environment allows you to communicate content in other ways so that you can capitalise on the features of the electronic medium and address different learning styles. For instance, visual learners will benefit from content interpreted visually. Images, graphics, animation and video can, in some cases, communicate an idea or concept more efficiently than words. This is evident in documentaries such as Walking with Dinosaurs. Here, not only the viewers were enlightened but the scientists also found they learned an enormous amount from having to visualise beings and events. Video and images can communicate context which is not immediately available to the learner. Obviously, video is a good choice for film and theatre studies.

Animations created by multimedia developers are an effective way of visually illustrating a concept or process involving movement, and these can easily be included in an online environment. If you are considering animations as an option (which will involve the costs and complexities of multimedia development) you should search first to see if a suitable example already exists as a reusable learning object. Many textbooks now have associated online learning centres which include animations that are accessible to the public.

Graphics such as diagrams, concept maps and mind maps can convey concepts and relationships between ideas. They can be used for navigation purposes, although introducing into an LMS a level of navigation that conflicts with the system’s navigation can be confusing. There are several software programs available for concept mapping. You could use one of these to develop comprehensive and informative maps.

![]() Aural content: An audio file can be useful when voice-based content, including tone of voice, is important or when you need to personalise learning. An audio with an image of the speaker can be used to introduce a subject or topic. The image provides additional information to students about the speaker. Audio files can also be used to convey real life sounds such as heart sounds and breathing patterns, and have use in music or in pronunciation for language learning.

Aural content: An audio file can be useful when voice-based content, including tone of voice, is important or when you need to personalise learning. An audio with an image of the speaker can be used to introduce a subject or topic. The image provides additional information to students about the speaker. Audio files can also be used to convey real life sounds such as heart sounds and breathing patterns, and have use in music or in pronunciation for language learning.

![]() Media databases: Your LMS may include a tool which allows you to develop a database of media items or terms such as a glossary or image library. Generally, students access items as required by clicking on hyperlinks in a list or table, which is located together with other resources for that topic. In addition, throughout the unit, hyperlinks to individual items can be automatically created whenever the name of the particular item occurs (you can control whether you want this to happen or not).

Media databases: Your LMS may include a tool which allows you to develop a database of media items or terms such as a glossary or image library. Generally, students access items as required by clicking on hyperlinks in a list or table, which is located together with other resources for that topic. In addition, throughout the unit, hyperlinks to individual items can be automatically created whenever the name of the particular item occurs (you can control whether you want this to happen or not).

Table 2.3 summarises some issues and questions you should consider when you are planning the provision of online content for your students.

If you want your students to view a video, large image files, or multimedia applications, the online environment may not be appropriate. These may be more easily viewed by students on a CD-ROM or DVD so that download time (bandwidth) is not an issue.

We will now move on to Web 2.0 and other recent internet applications so that you can think about how students might be able to meet additional kinds of objectives using these tools, or perhaps meet objectives you have considered in relation to the above options in more efficient or effective ways.

Web 2.0 and other new options for interaction

Web 2.0 environments are all about interaction and creation of content, and divisions between opportunities for interaction and opportunities for managing content become blurred. The technologies for managing content on the web remain largely the same (e.g., text, images, audio, video) but there is a dramatic increase in the way content may be produced, managed and shared, particularly in the context of interaction between users. Examples of Web 2.0 applications include social networking sites, image or video-sharing sites, blogs, wikis, mashups and folksonomies. These terms are described in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4

Recent technologies – some terms, definitions and examples

| Term | Definition/description | Examples/applications |

| Blog (Weblog) | Online journals or diaries typically ‘owned’ by individuals, with comments contributed by others | Sharing information and ideas |

| Folksonomy | Collaborative creation and management of tags to annotate and categorise content. Tags (metadata) are generated by users {social tagging), not only by experts {as in search engines) | Aggregating the tags of many users creates a folksonomy, e.g., Delicious |

| Web hosting service | Used to share specific content, connect with ‘like’ content | Image and video-sharing, online photo/video management and sharing applications, e.g. Picasa, Flickr, YouTube |

| Mashup | Digital media file containing any or all of text, graphics, audio, video, and animation, which recombines and modifies existing digital works to create a derivative work | Student projects |

| Mobile learning | Learning that takes advantage of mobile (portable) devices | Mobile phones: Text messaging {Short Message Service) to facilitate communication between lecturer and students Tablet computers: used in lectures or tutorials to enhance communication between teacher and students |

| Podcast | Audio/video which is syndicated, i.e. delivered via an RSS feed over the internet to a subscriber. Requires a host server | Content online; students create a site and connect with similar sites |

| Shared documents | Non-html documents which are editable online | Google Documents for word processing, spreadsheets, presentation and forms |

| Social software | Software which facilitates social interactions. Defining activities: conversational interaction, social feedback, and social networks | Social networking sites of which Facebook is just one example. There are many different social networking sites each with different characteristics |

| Virtual worlds | Online simulations such as those used in ‘the Sims’ type of computer games | Active Worlds, Second Life |

| Web 2.0 | Web development and design that facilitates communication, secure information sharing, interoperability, and collaboration on the World Wide Web | Web 2.0 concepts have led to the development and evolution of web-based communities, hosted services, and applications such as social-networking sites, video-sharing sites, wikis, blogs, and folksonomies |

| Wiki | Editable webpage ‘owned’ by groups | Wikipedia |

Table 2.4 indicates a range of options, some of which you may choose to use when you are familiar with working in online environments for teaching. The ways in which creation and manipulation of content occur are highly significant in terms of learning and teaching due to the implications for shared production online, and the opportunities for facilitating collaborative processes. Therefore, in this section, we will look at the affordances relating to interaction between users and interaction with content again.

Interaction between users

The proliferation of web-based social networking sites has highlighted the potential of Web 2.0 applications for communication and collaboration. Some use of the large privately-owned social networking sites is also being made for education, but you should think carefully about using these sites for teaching, taking into consideration issues such as:

![]() ownership of the information emerging from a learning-teaching interaction;

ownership of the information emerging from a learning-teaching interaction;

![]() your lack of control in that environment, relating to factors such as privacy, copyright, plagiarism, security of the data, and of your students; and

your lack of control in that environment, relating to factors such as privacy, copyright, plagiarism, security of the data, and of your students; and

![]() lack of integration with your institution’s administrative systems.

lack of integration with your institution’s administrative systems.

On the other hand, use of students’ ‘owned’ lines of communication (e.g., Facebook, SMS, Twitter) facilitates learning in ways which learners control and this encourages them to take responsibility for their learning and enhances their independence. However, they may not necessarily recognise the potential for learning of communication tools that they use for other purposes (Kennedy et al., 2009) and there is evidence that they may not appreciate intrusion on their social spaces (e.g., Sharples, 2007).

We will now cover some of the tools that may be available on institutional servers which allow interaction between users. We will begin by considering the nature of blogs and wikis and provide an overview of how they might be used for online learning or assessment, and then look at some of the other Web 2.0 communication tools.

Blogs

A blog (weblog) is a website where users can post contributions and comment on contributions or comments of others. Posts can be text or images and can include video or audio files. They are dated and presented in reverse chronological order (new ones appear at the top). They can be archived so that if a blog lasts a long time posts are categorised by date. Blogs are usually about making content freely available to anyone, getting your voice heard, and generating discussion around your area of interest. This may be in a global context or it can be limited to a smaller group of users.

![]() a personal one where only one person can post and those invited to participate can comment (this works well for a journalling or reflective activity);

a personal one where only one person can post and those invited to participate can comment (this works well for a journalling or reflective activity);

![]() personal for posting but open to all for comments;

personal for posting but open to all for comments;

![]() a group blog where several people can post and only those invited can comment; or

a group blog where several people can post and only those invited can comment; or

Table 2.5 summarises the configuration options.

Table 2.5

| Blog configurations | Who can add new postings? | Who can comment on existing posts? |

| Fully closed | Owner only | Invitees only |

| Closed post (‘normal’) | Owner only | Anyone |

| Invited post (‘group blogs’) | Invitees only Invitees only | Invitees only Anyone |

| Fully open | Anyone | Anyone |

For the purposes of learning in higher education, a blog might be used as a limited forum so that it can meet specific needs in a specific time, or it might be fully open if ‘authentic’ public responses are important in the context of the related learning objective/s. Blogs are particularly useful in allowing students to meet learning objectives that require them to reflect and record their responses. Blogs can facilitate online discussion of subject material as they can display both the material for discussion and the discussion thread itself on the same screen. See Figure 2.5 for an example.

Wikis

The word wiki is derived from the Hawaiian ‘wikiwiki’ meaning ‘quickly’. A wiki is a website which enables users to add to, edit and delete from the site’s content quickly. It incorporates a discussion space and a history for each wiki ‘page’. The history is a chronological list of all the changes that have been made to the page together with the identity of the editor. Previous versions of the page can be viewed and restored (if the changes are deleted).

Table 2.6 shows the different access levels that are available for managing wikis.

How can wikis be used in learning and teaching? In a face-to-face context, the output of group work is often a presentation supported with PowerPoint slides. When the group work cannot be accomplished or completed in ‘class’ time, preparing the PowerPoint file becomes cumbersome. The file must be sent between group members, introducing problems of time delay and version control. Further, the PowerPoint file format is designed to support a presentation rather than a standalone output, and there is no indication of collaborative inputs. Wikis address these issues and provide a number of advantages for group work.

Wikis are useful for student group work because the degree of collaboration can be monitored through the discussion and the contributions of individuals can be observed through the discussion and history. For the history to be informative the editing must be done using the wiki editor. A disadvantage of wikis at present is that the web editing is limited to text and images. However, the web editors used for wikis are increasingly complex and today’s limitations will be gone tomorrow. Wikis enable students to work online collaboratively on a single group output. The output (the wiki pages) stays on the wiki server so students do not have to download files, work on them and upload again. This gives students greater flexibility in group work as it alleviates the pressure to meet face-to-face.

Figure 2.6 shows an example of a wiki created by students as a group project. Students were given the task of diagnosing a medical problem, via a case study called ‘What’s wrong with Elisa?’ Resources were accessible in an LMS site and each group developed their analysis of the case in their group wiki. In this example the students have set up their wiki with links to sections in a navigation menu on the left. In the discussion associated with the homepage students negotiated the site construction, the content they were including in the site and project management issues such as division of labour, timelines and evaluation. The history allowed teachers to assess the contributions of students and track the development of the site by comparing versions of each page. In assessing the group project students were told that careful construction and editing would attract more credit than importing large blocks of text which might raise suspicions about plagiarism.

Shared documents

There are numerous applications for sharing web-based documents. Proprietary applications have extensive functionality for online collaboration (often used in research), but freeware is also available. The most popular application is Google Documents which allows web-based word processing, spreadsheet, presentation and form applications. This enables users to work on a shared document that remains on the server, which is useful for group work when the output required is in one of these formats. The focus of the technology is on the document and collaboration through discussion is not specifically facilitated.

Online videoconferencing and web conferencing

Online (PC) videoconferencing offers the potential of real-time communication that is much less cumbersome than text-based chat. Through online videoconferencing you can set up meetings with or between students and have some of the benefits of face-to-face interactions online. However, to take full advantage of the technology, users must have the client software installed and have a headset, microphone and a video cam. The client software is freely available, while the server software required to set up the ‘meetings’ requires a licence which may be available through your institution. Web conferencing (which allows all users to see the same screen at the same time in their web browsers) and online videoconferencing may be enhanced by other tools, including file sharing capabilities, whiteboards, chat programs and polling. Web conferencing may be used for purposes such as real-time meetings, presentations, demonstrations or ‘webinars’.

Mobile technologies and interaction

Mobile devices applicable to interaction for learning and assessment include laptop and handheld computers, portable digital voice recorders and, especially, mobile phones. At an institutional level, mobile phones are increasingly used to contact students on administrative issues such as enrolment, timetabling, venue changes, and notifying results using SMS (Short Message Service). Their use for learning is growing and applications include communication with and between students on placements or field trips.

Internet messaging such as MSN (Microsoft) can also be used to communicate with students and for students to communicate between themselves. This is more successful if students already use these technologies in daily life. These tools can be particularly useful for students collaborating in groups. They allow them to arrange meetings (virtual or real), divide tasks, etc. Skype is free software which allows users to make free calls over the internet to any other user who also has Skype. While this is mostly for two way communication, the technology can be used to hold a meeting of several people.

Electronic audience response systems can be useful in a lecture for diagnostic testing and engaging students. Tablet computers are increasingly used for this purpose. These allow input of data using a stylus or ‘digital pen’ on a touch screen, which can be combined with use of the keyboard for communication between users. They facilitate engagement and learning by students who can annotate online or prepare hand-drawn diagrams and communicate with the lecturer directly. The lecturer can then share selected contributions with the whole class.

Interaction with content… and other users

In addition to the interaction with content allowed by first generation internet technologies, Web 2.0 applications facilitate interaction with content in sophisticated ways which can combine with interaction between users. There are many examples of this type of interaction but it is exemplified in online role playing games described as ‘massively multiplayer online role playing games’ (MMORPG) in which a very large number of players interact with one another within a virtual world.

Games, simulations and virtual worlds

While social software facilitates communication between users and with content which is largely determined by and controlled by the user, gaming software is designed to facilitate interactions which, at least to some extent, are controlled by the software designer. Gaming software is used for a wide range of simulation software designed for learning and teaching. The development of such software has flourished in the area of technical instruction, resulting in sophisticated software in industry such as the flight simulator. Games such as those from the Sims franchise (e.g., SimCity) were developed for the commercial market and originally predated Web 2.0 applications. However, use of the newer technologies facilitates and extends the development and implementation of software based on a ‘game’ metaphor.

If some of your objectives require experience-based learning, Web 2.0 applications which support games, simulations and virtual worlds with immersive, collaborative engagement through designed experiences (Squire, 2006) may be relevant. Authentic challenges are presented in narrative social spaces, requiring the collective action of the players (Amory, 2007). Reeves, Malone and O’Driscoll (2008, p. 64) note the benefits for life and work of merging real and virtual worlds (for example, ‘online games can be informal but realistic simulators for contemporary leadership training’ that is immediately applicable in business).

In Table 2.4 we listed two examples of virtual worlds (Active Worlds and Second Life) which are commonly used in education, but there are dozens of platforms available. Integration of virtual worlds with learning management systems is in progress but the time and expertise required to create the world and then work within it make it a high risk choice for learning, particularly if you have not taught in the online environment before.

While some of these environments are widely used socially as web-based multiplayer role playing games, their uses for learning are still limited. If you are considering role playing as a learning activity, and are new to online teaching, it may be best to begin to explore your ideas using pre-Web 2.0 applications initially (such as role playing in online discussion groups). While less exciting, this will allow you to clarify your educational strategies and gain experience before applying these ideas with more complex technologies.

Web 2.0 and other new options for managing content

One of the key advantages of Web 2.0 applications is the ease with which they allow development and sharing of content (both visual and textual) by users. While delivery of content by the teacher is not precluded, your main emphasis in relation to content if you are considering the use of Web 2.0 applications may be on objectives that require students to organise or generate content themselves. This may involve web publishing that includes not only text, but also audio and video content and images, enhancing the auditory or visual authenticity of the activities they undertake to meet the objectives.

You should also be particularly aware of the opportunities offered by web syndication and podcasting.

Web syndication

Those who use Web 2.0 applications in a global context (rather than a limited project-based context) value web syndication. This is where content in a website is made available to other websites to use, usually in the form of ‘web feeds’. These web feeds are lists of new content from a website, for example, the latest post from a site. The web feed notifies subscribers of the latest content on your site and notifies you of the latest information on the sites of others. In this way a website (such as a blog) links to other websites with a common interest. By choosing the web feeds you want to use (subscribing) you can tailor the connections you make with others through your website, or have the latest information emailed directly to you through an aggregator.

There are several formats for web syndication. They are collectively called RSS feeds (for Really Simple Syndication or Rich Site Summary), and RDF (Resource Description Framework Site Summary), and they use a site’s metadata to generate the feed.

Web feeds are useful from an academic perspective to keep track of new information in your area which can be relevant to you and your students.

Social bookmarking sites allow users to build content they can share using RSS feeds, while aggregators allow organisation of the content that is generated.

Podcasts

Podcasting is used to deliver audio or video to users as mp3 or mp4 files downloaded from the internet. The audio or video file itself is not a podcast, nor is an embedded file in a webpage.

The downside of podcasting, from the perspective of online learning design, is that there is a tendency to use it to replicate face-to-face teaching by podcasting lectures, without thinking about reconceptualising teaching to take advantage of what the technology offers. Barnes and Tynan (2007, p. 192) make this point in the following comment:

Most podcasts are last year’s lecture in digital format. Student remixing of podcasts, use of syndication to pool collective responses and other more active learning approaches are losing out to those that see podcasting as a high-tech alternative to the audio cassette of the 1980s. To avoid this outcome, university policy-makers and teaching staff alike need to listen to the call for fresh pedagogies …

Mobile technologies and content

Specialist portable electronic devices for reading text, taking photos and recording audio are continually coming on the market. They range from laptop computers designed for annotating (e.g., Tablet PCs) and reading text (e.g., iBooks) to mp3 players (e.g., iPods) and mobile phones (e.g., iPhones). Apple Inc specialises in such idevices. They have many benefits, such as reducing the load of books that students carry and facilitating creation of content by both teachers and students. Building the use of such portable devices into learning activities for students raises an equity issue for those who cannot afford the device or a funding issue for the institution or faculty if the devices are provided for students.

Portable digital devices such as cameras and voice recorders enable you as a teacher and your students to easily create content in different forms. This allows you to add visual and aural dimensions to your teaching materials addressing a range of learning styles with images, video and audio. It similarly increases the ways in which students can present their responses to learning activities or assessment tasks.

Even newer options …

Software which uses ‘audit trail’ data to determine ‘characteristics’ of users (learners) can help to tailor learning for an individual based on previous choices that they have made. In the commercial sector these Web 3.0 applications will enable advertisers to target advertisements to those who are most likely to ‘buy’, thereby not wasting marketing on those who go into ‘mute’ mode. As for Web 2.0 applications, Web 3.0 is more a case of using the data more effectively and efficiently, in this instance by adding new metadata to the web, rather than creating a new paradigm.

Another development to be aware of, which could affect your options, is the proliferation of open source applications (named because of the free availability of the source code for modification) which are challenging the rigid and costly proprietary learning management systems, potentially providing for greater customisation at institutional level. Nevertheless, as Dron (2007a, p. 219) explains:

Open source is an approach, not a technology, so it requires programmers with relevant skills to implement changes. This makes it very far from free to implement successfully within an institutional context, and the cost may be similar to or greater than that of the commercial equivalents.

The open source collaboration tool Google Wave promises to facilitate online interaction and collaboration through seamless integration of internet capabilities.

While the summary of technology options in these sections does not cover all of the huge range of possibilities you could consider, you should now have some sense of the kind of online learning tools that you might use to allow students to meet the objectives you have specified. You will need to choose your options within the constraints of the technology options that are readily available to you, which we discussed earlier, and also bearing in mind the kinds of student support, management and administrative issues which we will address in the following sections.

You were probably aware, as we moved through some of the technology options, that you had a clearer idea of how you might implement some of them, compared to others. We will now look at some further issues relating to teaching with technology which you will need to think about before you make a final decision about your technology options. We will cover additional issues which relate to online learning design and development in Chapter 3, and to online assessment in Chapter 4.

Student support

We have already mentioned the benefits of institutional systems in relation to the backup procedures and access to technical support that are usually associated with them. The support issues that you need to consider when you are choosing your technology options include support for your students and support for you in managing the environment. It is likely that you will be responsible for much of the former, at least in terms of guiding students to the support that is available for them. In relation to the technologies you choose, you should be able to:

![]() develop contingency plans for unexpected technical problems, and communicate these to your students;

develop contingency plans for unexpected technical problems, and communicate these to your students;

![]() ensure that appropriate support systems are in place for students and that they know how to access them, taking into consideration issues such as access and equity, variations in competence with the technology, the needs of international students and any costs or ethical issues; and

ensure that appropriate support systems are in place for students and that they know how to access them, taking into consideration issues such as access and equity, variations in competence with the technology, the needs of international students and any costs or ethical issues; and

![]() ensure that students are able to access the sites or systems required (issues may include problems with usernames and passwords, browser configuration, or lack of broadband access if they are using dial-up modems from remote sites).

ensure that students are able to access the sites or systems required (issues may include problems with usernames and passwords, browser configuration, or lack of broadband access if they are using dial-up modems from remote sites).

Remember that each additional tool you use in online teaching may involve a learning curve for your students so you may need to consider whether they have used these tools before in the context of their characteristics as learners which you addressed in Chapter 1. If any of the above are likely to be problematic, you may need to reconsider your options.

You will also need to think through how you will communicate important information to your students in order to support them. If you are not teaching in a context that includes face-to-face contact, you will need to consider carefully how you will provide instructions and perhaps give students the opportunity to practise. Two-way synchronous communication may be beneficial in this situation but it may not be possible to arrange unless you have face-to-face access to your students. Online chat, desktop videoconferencing or web conferencing potentially create additional barriers because they can be difficult in managing group communication.

Management and administrative issues

While having access to technology and to technical support are fundamental to successful teaching or assessment, you also need to know how to use the technology, and especially how to use it in pedagogically appropriate ways, in order to be able to communicate relevant teaching information to your students. Even though you are making your technology choices based on pedagogical decisions determined by the learning objectives, you may still need assistance to reconceptualise your teaching in order to teach effectively in this environment, drawing on the knowledge that has already been generated in the field.

The quickest way to do this is to check out the staff development opportunities that are easily available to you in relation to the technologies that you are considering. As well as formal staff development offerings, this might include talking to colleagues who have already used the technologies and gaining advice from them. We will consider some specific issues relating to pedagogy and online design and development in Chapter 3 but at this point it is important to establish whether or not this support exists.

An important general point to think about now is that if you have identified multiple objectives which suggest multiple technologies, it is probably best to scale back your plans and begin with the objectives that you consider to be most important and the technologies that will be simplest for you to manage. If you are teaching in a face-to-face or blended learning environment, consider dealing with only one component first, so that you can trial and evaluate that before adding others. If you are planning a fully online course, you will need to encompass all of the objectives but it is still best to start with technologies that you and your students are familiar with, if possible.

You also need to think about the nature of the technologies themselves, and their implications in terms of management and administration, including the workload for both you and your students.

Deciding your options

You should now be in a good position to decide what your options are in terms of your choice of technologies. Your decision will be embedded in the pedagogical decisions you made in Chapter 1 and will be particularly driven by your identification of learning objectives. You will have noticed how each of the factors you have considered in this chapter has narrowed your options and provided a clearer focus on the technologies you will need. In practice, depending on your knowledge of available technologies, this process may be almost instantaneous. What we have aimed to do in this chapter is to break down this process into some of its component parts and illustrate the importance of keeping your eye firmly fixed on the pedagogical factors underlying your choice.

While there are further important issues to be addressed in Chapter 3 in relation to online learning design and development, the issues you have covered so far should be sufficient to enable you to decide what you will need in terms of technologies. These subsequent decisions will determine how you will use the technologies you have chosen.

Illustrating the ideas in this chapter …

To illustrate what we have covered in this chapter, we continue Suzy’s story which began in Chapter 1.

Summary

Drawing on the learning objectives you identified in Chapter 1, this chapter has covered some of the main issues that you need to consider in identifying your technology options. You have now thought about the affordances of the technologies you require, as determined by these objectives, and the role of your institution’s policies and infrastructure in influencing your options. You have looked at a range of technologies that are available for use in education and you have considered some student support, management and administrative issues that you may need to address to finalise your choice.

You should now be clear about what your technology options are, taking into consideration any additional factors relating to your learning and teaching context that you did not think about in Chapter 1. In Chapter 3 we will move on to the design and development decisions you now need to make, which will bring you back to thinking about the nature of student learning.

Following is a continuation of the checklist which you began in Chapter 1. It encompasses the main planning stages we have covered in this chapter. If you are able to answer ‘Yes’ to most questions here, you will be ready to begin the design of your online environment. If your answer to most questions is ‘No’ (and assuming that your initial plans from Chapter 1 are in place) you will probably need to undertake further exploration of possible learning technologies. Remember that using technologies supported by your institution will probably be the easiest way to start, even if it involves some modifications to your plans (which do not threaten the learning or assessment benefits). If you need to explore the technologies further, developing the skills to use them is one dimension, but exploring how to use them effectively for learning or assessment is most important.

1In this book we use the terms ‘learning management system’ or ‘LMS’ to refer to proprietary learning management systems and virtual learning environments.