Employee resourcing

2.1 Introduction

We have so far looked at HRM in terms of its common aspects, broad coverage, development and links to strategy and tensions within it. This has given both an overview and framework for the rest of the book. We now shift our focus towards the key initial area in HRM – employee resourcing. How do organisations staff and make operational their business strategies? This concerns the utilisation of HR planning (HRP). A second key aspect of this is employee recruitment and selection. Once strategic and business plans are formulated, how are they ‘resourced’ with HR? In considering this, we will draw attention to the major differences in resourcing in Asia compared to Western models.

2.2 Overview

HRP is concerned with the acquisition, use, improvement and preservation of an organisation’s employees to match its business plans. It attempts to reconcile HR ‘demand’ (forecast from extrapolating corporate plans) and ‘supply’ (forecast by working out the availability of HR and calculating likely shortfalls and surpluses). In short, HRP identifies the key characteristics and behaviour of the HR ‘stock’ and ‘sources’. This identification includes the individual’s length of service, general statistics on turnover, absenteeism, skills, and so on. Also, part of this HRP involves so-called ‘environmental scanning’.

HRP aims to control costs by helping to anticipate, or correct, HR shortages or surpluses before they become unmanageable and expensive – as the maxim goes, to ‘employ the right number of people with the right skills at the right time’. In parts of Asia, as a result of the prevalence of low added-value work, the emphasis has been on the ‘right number’ and ‘right time’ and the ‘right skills’ has often been ignored.

In the West, especially between the 1950s and 1980s, HRP was seen to have a crucial role, particularly in large organisations operating in stable operating environments. In the West today, however, even in the largest organisations HRP is sometimes seen as less useful, just as it has been viewed in small firms and in more volatile contexts. In parts of Asia small firms are an important part of the economy and some Asian work environments are volatile, so HRP is less practised – with damaging consequences for the population as well as for the resources of the Asian countries.

The idea of the so-called ‘flexible firm’ is one response to this volatility. As was outlined in the previous chapter, in this model the business has a stable ‘core’ of employees who are flexible functionally in terms of jobs and skills. This is surrounded by a ‘periphery’ of other workers who are flexible numerically in terms of their numbers and which can quickly and easily be expanded or reduced in size to reflect business requirements. This second group are seen to act as the ‘shock absorbers’ of the business, there to ‘soak up’ variations in demand, and so on. Another version operates between firms, whereby Asian small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are often treated as shock absorbers by governments and by larger organisations, although some SMEs have long-term, stable and close relationships with these organisations, as is common in Japan.

The HR resourcing of organisations is sometimes treated in a manner that has been labelled a ‘downstream’ or ‘third-order’ activity (by Purcell; see Thornhill et al., 2000: 98–100) – that is, an activity which follows in the wake of the business strategy and which HRM practitioners implement in a somewhat mechanical fashion. In other words, at times HR resourcing is not considered in strategic decisions until late on, or it is considered to be neither that important nor very difficult to achieve. Furthermore, some actions and decisions in the area of employee resourcing may not be internally integrated or ‘joined up’. There may well be the management (even political) will to ‘do something’, but the implications are not always thought through. In parts of Asia, HR resourcing, except for the most senior or influential jobs, is definitely ‘third order’.

We consider what might be the problems with this view that HR resourcing is not very important or not very difficult and what are the influences on resourcing an organisation with employees to deliver and fulfil its business strategy? We will explore these issues here and develop models to look more coherently at employee resourcing. We will see that in some rapidly modernising economies of Asia, HR are considered to be so freely available that the potential contribution of HRM is overlooked. This neglect of the application of systematic HRM techniques is damaging to organisational success because, although HR may be plentiful, they are generally of the wrong type and are often selected on the basis of factors other than capability.

Following this first main section of the chapter we move on to the subsequent substantive part of employee resourcing – that is, recruitment and selection. This topic has been summarised by some as meeting HR requirements by defining vacancies, attracting applicants, assessing candidates and making the final decisions. The area is one of the key activities to achieve important HR and organisational outcomes in some HRM models. We will see that in parts of Asia, HR resourcing is sometimes handled very differently from Western standard methods.

Once the HR plan has been developed, how is it to be implemented? This can be achieved by using a wide variety of quick and simple to long and complex recruitment and selection techniques. Yet, why should organisations invest in sophisticated, but often costly, recruitment and selection? Indeed, there is evidence that some organisations often fail to take this process seriously, while others believe that it is crucial to future success. In parts of Asia some organisations do not take recruitment and selection seriously nor use the processes effectively, as they prefer more non-objective and less systematic methods, as we will see.

While there are many recruitment and selection techniques, much research indicates that most organisations have often relied on the ‘classic trio’ of methods – application forms, references and interviews. This common use of the trio is despite evidence of problems with these methods in themselves, along with their poor reliability as predictors of job performance. There is also some interesting variability in the use of recruitment and selection methods between businesses across different countries in the West as well as in Asia.

Some of the implications of contemporary developments in employee resourcing in Asia can be seen in reports in the mass media, such as The Financial Times. For example, Nakamoto (2006), Lucas (2008) and Whipp (2008) cover some of these in relation to Japan, as does McGregor (2009) in relation to China.

2.3 HRP

HRP is seen as providing organisations with the possibility of reaching the ultimate goal of employing the ‘correct’ number of people with the requisite skills at the right time. In theory this sounds eminently desirable and achievable and not too difficult, only requiring HRM departments and managers simply to take into account relevant organisational plans and circumstances and then organise the commensurate HR and actions accordingly. We consider later how this might be achieved. We can see HRP issues in the example of China given in Text Box 2.1.

2.4 Activities in HRP

Given the above, it can be seen that there are several main activities and stages in HRP. These include the following.

2.4.1 Forecasting demand for HR

HRP is just one element in corporate planning, and cannot be isolated from the organisational planning process as a whole. In order to put into effect the organisational strategic plan, a number of more detailed business plans need to be produced and reconciled with one another. These include, for example, the following:

![]() marketing plans, outlining which products will be offered and in what quantities;

marketing plans, outlining which products will be offered and in what quantities;

![]() operations plans, specifying methods of production, distribution and development; and

operations plans, specifying methods of production, distribution and development; and

HR plans specify the HR needed to execute these business plans. HRM managers need to integrate their HR plans with those of other departments if they are to operate strategically. A demand model is then constructed and data fed in to produce estimates of the required HR levels to accomplish the strategic and business plans.

2.4.2 Forecasting supply of HR

HR supply (from both existing and new sources) needs to be examined, calculated and forecast. This involves the use of a range of data and projections.

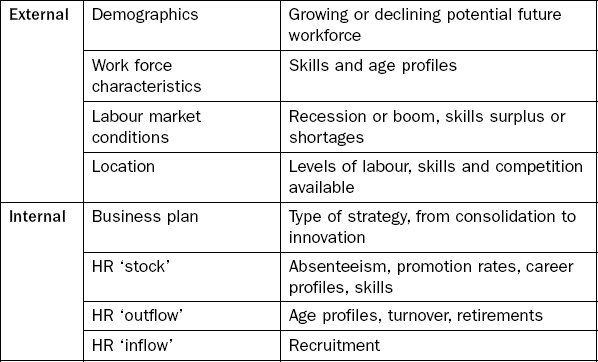

The data includes the source of supply (ILMs or ELMs) and skills, profiles, characteristics and behaviour of the required HR and projections of likely influences on this supply. This includes the following, as noted in Table 2.1.

2.4.3 Action and assessment

Following the exercises described above and the collection of relevant information, HR action plans need to be developed and implemented to reconcile HR demand and HR supply and resolve any expected discrepancies in order to produce a close fit of demand and supply. These HR action plans can involve recruitment targets, selection criteria, promotion policies, (re)training, redeployments, redundancies and retirements. An initial HR plan is monitored and evaluated. The achievement of goals is assessed, and changed to meet new conditions and recover from mismatches. The flow of HRP can be seen in the various versions of traditional models of HRP, as outlined in Figure 2.1.

By such means as the above it is argued that HRP will reduce the costs of the organisation by helping to anticipate and correct HR shortages or surpluses before they become unmanageable and expensive. Furthermore, such plans can provide a better basis for other areas of HRM, such as employee development, in order to make optimum use of HR and to improve employee morale and motivation. By using this planning activity, potential problems and future organisational requirements may be identified and appropriate action taken. However, as with most HRM responsibilities, HRP involves many activities and does not proceed in a linear fashion. Rather, it is an iterative process with feedback to ensure consistency, coherence and integration of the plan.

2.5 Methods and data in HRP

There is a range of possible methods and data that could be utilised in HRP; these are now outlined.

2.5.1 HR databases and analytical software

An initial starting point for HRP is to examine any corporate databases. Here production rates, salaries and financial files can be drawn upon, as well as the main HRM records containing basic facts in a structured format, records of performance appraisals and other reports. These sources can give profiles (such as length of service, skills and qualifications) by section of the existing workforce. A HR information system (HRIS) is most useful in HRP. Larger organisations can use specialist software and sophisticated methods from suppliers such as Oracle and SAP. In contrast, smaller organisations may meet most HRP needs through the use of general purpose analytical tools such as spreadsheets.

In some parts of Asia the use of an HRIS is rare and information technology (IT) applications are concerned with financial data, so the only HR aspect that IT systems will be concerned with is payroll. Personal files of staff are most likely to be held in paper formats, making production of a computerised database laborious.

2.5.2 Work study

One initial question will be: even if ‘output’ (manufacturing and services) requirements and details of existing HR are fairly certain, exactly how many, and what type of HR are actually needed to resource a business or HR plan? This is where work study can be used to compute standard times and standard work methods for different jobs (this area is returned to in the second part of this chapter). Sales and production forecasts can then be used as a basis for HR demand forecasting. These methods work for the analysis of existing operations and jobs but, obviously, are less useful when new operations and methods of production and services are involved with the uncertainties they bring.

In some organisations in Asia work study tends to be based on historical data rather than the production of standard data. Pieceworking (pay for the number of items produced) is common, with work periods extended to cope with new orders and reduction in working days/weeks if orders drop. In some organisations, particularly those that are government owned, productivity is not considered and numbers of employees are based solely on ‘political’ and historical factors – topics that will be discussed later.

2.5.3 Modelling techniques

Another critical area of HRP is where business output, and hence HR requirements, are variable over time. Here linear techniques and other statistical models can be used in forecasting and to investigate relationships between variables. These techniques can be used to project future demand based on previous HR levels and sales or relate employment to a variety of factors, such as how technology or market growth will affect employment. A simple example of this is time series analysis, which can be used to look at previous capacity and resourcing and predict future demand and therefore likely HR requirements, all things being equal. Examples here include organisations that face predictable daily business variations and flows (such as those in retailing or banking) or annual production or service demands (such as certain seasonal foods and products, or hotels where staffing will reflect occupancy rates).

Of course, time series modelling is based on beliefs that the future will follow the past. In reality, sudden unforeseen events can make such assumptions redundant, an example being the Hong Kong hotel and restaurant sectors in the wake of SARS with the collapse in demand and hence need for HR. A further example is the post-2008 global financial crisis, which undermined output and growth predictions, and hence HR requirements, in sectors from financial services and aviation to construction and manufacturing.

Asian organisations can analyse daily and weekly data but few, mainly in East Asia, have had the economic stability that aids modelling as their societies and economies are changing so rapidly. In South Asia, India experienced rapid growth, particularly in IT and outsourcing industries, so modelling is often based on data gleaned from other regions.

2.5.4 Key statistics

To assist in HRP various key statistics may be computed by organisations. These statistics are also sometimes used as barometers of the ‘health’ of the organisation and behavioural aspects of work in areas such as job satisfaction, morale and working conditions. These include the following types of data.

2.5.4.1 Labour turnover

Labour turnover is described by a variety of other terms, including wastage, attrition, ‘quits’, leaving, drop out, exiting, and so on. This is a key HR statistic, not least as labour turnover can be costly to many organisations. Nevertheless, turnover is not always problematic – for instance, in fast food retailing where the costs of recruitment and training are low. Some HRP outputs, such as those for redundancies, are radically affected by such rates of turnover. For instance, organisations with high rates of turnover face different choices if redundancies are required or training is being considered when compared to those organisations with low rates of turnover.

Importantly for HRP, a variety of reasons for turnover exist, some of which can be foreseen and hence planned for (such as retirements), although others may be less predictable (such as voluntary resignations or dismissals). Critically, labour turnover can be measured to provide an index for comparative reference and some basis for trends. The following shows a common method of calculating turnover.

A simple example of the labour turnover of tellers employed in an Indonesian bank illustrates this. Here the average number employed during the year is 1,000 and the number who left employment during the year was 100. This gives a turnover rate of 10 per cent:

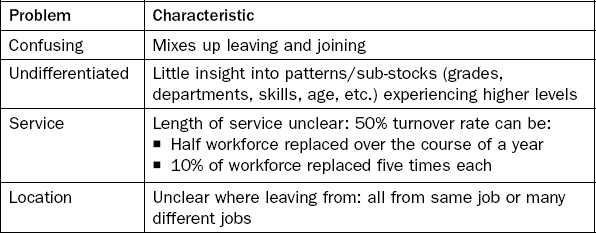

Labour turnover, however, is a complex and interactive phenomenon. Therefore, problems for management and organisations can result from reliance on using just simple labour turnover rates.

These problems are varied. They include those noted in Table 2.2.

2.5.4.2 Stability index

Other, more differentiated, data can be generated for use in HRP. These include the development of a stability index, which is used to counter possible distortion of the figures for turnover by short-service leavers. It is calculated as follows:

We can continue to use our earlier example to illustrate this. It will be recalled that the Indonesian bank employed 1,000 tellers, but had a 10 per cent turnover rate. However, the number of tellers with one year’s service or more was 950 and the number employed a year ago was 1,000. Hence, the bank actually had a stability index of 95 per cent, calculated as follows:

Taken together, an organisation’s turnover and stability index can show if there is a narrower problem with just a few positions, or a wider problem and with many positions. This distinction is important and a critical factor in HRP, as well as HRM practices and decision making.

2.5.4.3 Fringe turnover index

A further statistic that may be used by organisations is a fringe turnover index. This calculates the percentage turnover of short-term workers. Importantly, this distinguishes those who join and quit quickly from the overall turnover figure. This figure is calculated as follows:

Still using our earlier example to illustrate this, we can recall that the Indonesian bank employed 1,000 tellers, but had a 10 per cent turnover rate. However, the number of tellers joining and leaving within the year was 200. Hence, the bank actually had a fringe turnover rate of 20 per cent, calculated as follows:

2.5.5 Early patterns of wastage

From the organisational examples given above, we can see that many new recruits leave quickly but once tellers have been with the bank for a year they are much less likely to leave. We will now discuss why this might occur. Statistics can show HRM when people are likely to leave. Research in this area has found ‘phases’ which form patterns – for example, the ‘Three Stage Theory’ of wastage. This is composed of the following: first, there is the induction crisis, where there is initial shock, false expectations and a lack of identity. This is followed by the differential transit phase, when people start to assess the organisation and whether they have place in it; and finally the settled connection stage results as ‘survivors’ become established employees with commitment to their employer.

It should be noted that this theory assumes employee choice. However, as will be seen later, many employees, as is the case in parts of Asia, have little choice in their source of employment, and employers and labour supply agents find a variety of means to prevent employees from leaving.

2.5.6 Absenteeism

Another useful statistic for organisations concerns absenteeism. This can be measured in several ways, which include measuring (a) the percentage of lost working days, (b) days lost per working year, and (c) average length of absence.

Absenteeism is often a serious problem for employers in the West, whereas in parts of Asia few employees, except those with permanent jobs in government service, are entitled to sick pay and great pressure is put on individuals by employers and fellow workers to attend work. However, there is also a tradition in parts of Asia, as a result of poor government services and culture, where family pressure is often applied for people to attend to personal matters (such as disputes with neighbours, family illness or to accompany a close relation who is travelling), which can result in employees being absent for extended periods.

2.6 Impacts on HRP

From the above it seems that HRP should be a most useful tool and resource to aid management and organisations. What then accounts for the common finding that HRP is of limited use in reality? An immediate problem is that organisations do not exist in a vacuum, nor are HR inanimate objects. Rather, variations in organisational size and changes and trends in environments (internal and external) all have influences. At the same time, humans are complex social beings. These factors impact on the assumptions upon which planning is based: unreliable, changeable and tenuous. This can be seen in the following examples of impacts on HRP.

2.6.1 The impact of organisation

HRP techniques can vary in their sophistication and in their use – for instance, between:

![]() large businesses, which traditionally used sophisticated HRP techniques – examples include international oil companies, public sector groups and commercial banks; and

large businesses, which traditionally used sophisticated HRP techniques – examples include international oil companies, public sector groups and commercial banks; and

![]() smaller and less complex organisations, which used simpler HRP techniques, or even ad hoc judgement – examples include maintenance companies and retail outlets.

smaller and less complex organisations, which used simpler HRP techniques, or even ad hoc judgement – examples include maintenance companies and retail outlets.

Linked to organisation variables impacting on HRP is the operating environment and its level of stability. In the case of parts of Asia, the environment can be dynamic and unpredictable (see Studwell, 2002).

2.6.2 The impact of environment

Changes in the external environment have critical impacts on HRM, as we saw in Chapter 1. To minimise the problems from these external factors, organisations can monitor their environments in various ways, using a range of sources. These include surveys, trade association networks, news media and journals. HRP was valuable to large organisations operating in stable environments.

In this respect, a classic example was Indian retail banking before the 1990s when management and trade unions were able to prevent changes in technology and service standards, so maintaining a stable environment. HRP may be useful in such circumstances. For example, the armed forces, civil service, local government and education change slowly or in predictable ways and therefore place more reliance on HRP. In contrast, for organisations in environments that change more quickly (such as Chinese retail banking post-2000), the value of HRP, especially in its more detailed aspects, is more questionable and difficult.

Volatility in demand is not a problem per se for HRP, because these fluctuations may be somewhat predictable over time, as was noted earlier with the use of time series analysis. However, when customer demand is volatile and unpredictable, greater problems may arise for HRP. This issue of the unreliable nature of demand figures on which HR estimates are based can be difficult to manage.

Another problem is that some of the assumptions on which HRP is based turn out to be wrong. For example, the 1980s debate on the so-called ‘demographic time bomb’ predicted a shortfall in younger workers caused by falling birth rates and increasing educational participation (i.e. young people staying longer in school and higher education), with commensurate difficulty in finding HR for those sectors that normally recruit young people for their operations. This did not materialise. While this was an issue of concern for many countries again after 2000, it also has a longer lineage, such as in the UK in the late 1980s.

In some parts of Asia the main problem is the rapid increase in the number of young people seeking or soon to be seeking work (see, for example, Harry, 2007). In contrast, there is China’s demographic ‘time bomb’ of an aging population resulting from its one-child policy since the 1970s with India’s demographic ‘time bomb’ of a rapidly growing population of working-age adults. Both countries have a surplus of males in relation to females because of cultural preferences for male children. There is much concern in Japan and South Korea with falling birth rates and consequent declines in typical indigenous labour supplies. Options to address this could be both internal (for example, better utilisation of existing HR such as older adults) and external (for example, use of migrant workers). However, these strategies may face specific Asian cultural constraints, such as restrictive views on gender and ethnicity (see Rowley and Yukongdi, 2009).

However, in many Asian organisations, especially government-owned ones, and in environments where trade unions or political movements are strong, the number and type of staff employed may be based not on the need for a job but on the need to gain favour with influential factions. In most of South Asia a political party, when coming to power, will instruct the civil service or major employers to create jobs for its supporters and resistance to these demands is impossible to contemplate. Yet, the supporters of the previous regime rarely lose their jobs, so the organisation becomes over-staffed. However, few of those appointed are expected to actually work. In a similar way, strong trade unions will fix the numbers to be employed and will resist changes which could make the organisation more effective. For example, well into the 1990s Indian trade unions prevented the introduction of computers into state-owned banks. An extreme example of the impact of outside forces on recruitment is found in Lebanon, where jobs are reserved for members of particular religious groups or sects. Thus, in the Beirut Ports Authority, crane drivers are all of one sect, warehouse staff of another, and so on throughout the port.

2.6.3 A flexible response

Given the above factors, some organisations respond by abandoning detailed HRP in favour of a more flexible response (as we saw in Chapter 1 and the discussion of flexibility and the flexible firm model). Here organisations adopt a strategy of retaining a core labour force in permanent employment whilst having peripheral workers who can be recruited or laid off at short notice. Examples of these have come to light in the post-2008 global financial crisis, such as in the UK with BMW’s Mini car factory in Oxford. The core itself can also have some flexibility, such as in the hours, days and weeks worked, and so on. Again, examples of these have appeared as a response to the impacts of the post-2008 financial crisis.

However, whilst pointing out some limitations to HRP, this flexible approach may not totally invalidate the HRP process. The HRP process can still be used to anticipate and prepare for events. It can also involve thinking critically about existing arrangements and performance. Thus, HRP can help to avoid some serious problems.

2.7 HRP in practice

We can see the impacts of failure to use HRP in a range of examples, as shown in the case studies in Appendix 3 and the text boxes below. The issues raised in the case studies provide salutary warnings about the consequences of ad hoc, short-term decisions and impacts on, and from, HR. These can critically undermine organisations and their business strategies.

Once the issue of HR requirements via HRP of some form or other has been resolved, one implication may be the need for more HR. This is the topic of the second main part of this chapter.

2.8 Recruitment and selection

Recruitment is the process of contacting suitably qualified applicants (internal and external) for a vacant position and encouraging the suitable people to apply. Selection is the process of matching the attributes of candidates with the requirements of the job and then choosing the most appropriate applicants for the vacancies. Interestingly, in the early 1990s in the West, it was argued that the desire for a flexible, multi-skilled workforce in which team working was more prominent meant recruitment and selection was less about matching individual people to the fixed requirements of individual jobs at a single point in time and more about having candidates with a range of skills who were able and willing to work together. Consequently, immediate skills and background were less important relative to criteria such as willingness to learn, adaptability and ability to work in teams (Beaumont, 1993: 56). There are obvious implications in these ideas for employee resourcing which we will discuss later.

We saw in the earlier section of this chapter on HRP that job vacancies occur for a variety of reasons. These include internal growth within the organisation, as well as HR leaving their positions as a result of, for example, retirement, resignation, promotion, transfer and dismissal. How does an organisation go about filling any resultant demand with suitable HR? The case for systematic and effective procedures and methods seems to be incontrovertible given factors such as the:

![]() need to comply with laws, such as those concerning discrimination;

need to comply with laws, such as those concerning discrimination;

![]() mass of evidence demonstrating the costs of mistakes in recruitment;

mass of evidence demonstrating the costs of mistakes in recruitment;

![]() impact on the image and reputation of an organisation from having the ‘wrong’ recruits.

impact on the image and reputation of an organisation from having the ‘wrong’ recruits.

Legal intervention includes laws to both ban and institutionalise discrimination on the basis of gender, race and age. This include laws which impose positive discrimination, such as those that apply to the scheduled castes (dalit or lower castes) in India or Bumiputras (Malays and other ‘sons of the soil’) in Malaysia.

In parts of Asia recruitment has for a long time depended more on ‘who you are’ and ‘who you know’ rather than ‘what you know’ – an advantage which, as we saw, has only recently been identified in the West. Some Asian employers will seek candidates among relations or friends of existing staff or among other contacts. Therefore the most appropriate recruit might not be the one who has the most ability (see, for example, Weir and Hutchings, 2006).

However, if HRM is able to demonstrate that systematic recruitment and selection can contribute to organisational effectiveness, there will be a shift in the focus of selection. Lest the Western reader feels that selection based on ability is a Western innovation, it should be recalled that for over a thousand years the Chinese Empire’s system for appointing senior officials was based on merit (passing examinations), while it was only in the mid-nineteenth century that ability started to replace social status as the primary method of making appointments in the British civil service and the army. The British army relied upon officers buying commissions until the greater effectiveness of the army of the East India Company, based on promotion by ability, was shown in the Crimean War and other conflicts.

2.9 Stages

There are several stages in the recruitment and selection process. This involves assessments of both:

These phases and activities can be seen within a comprehensive recruitment procedure, as outlined diagrammatically in Figure 2.2.

An initial question may be: what exactly is the post that needs to be filled and what does the job actually involve? After all, if we do not know this, how can we judge who might be the ‘best’ person to fill it? Thus, before recruitment begins, information on key elements of the job is needed. This involves job analysis and its output.

2.9.1 Job analysis

Job analysis is used to elicit what a particular job is about and what it actually involves.

This can include a range of methods. Some of these are highlighted inTable 2.3.

Table 2.3

| Method | Characteristics |

| Work study | Examine each aspect of job |

| Questionnaires | Details of what job holder does |

| Interviews | As above |

| Work diaries | Detailing tasks completed each day |

| Critical incident reviews | Records kept |

| Observations | Supervisor’s comments |

| Panels of experts | Ask what might be details of new jobs |

2.9.1.1 Time and motion studies

One method of analysing jobs is work study, which includes ‘time and motion’ studies (as was noted in the first part of this chapter). The job analyst, who may be an insider (generalist or even specialist) or an outsider (consultant or contractor), studies selected employees ‘at work’, recording and measuring their activities over a sustained period of time. Each task is broken down into individual elements and the way in which these are carried out is examined microscopically. This is the basis for Scientific Management and Taylorism.

2.9.1.2 Questionnaires

Questionnaires are another method used in job analysis, and can be specifically designed or standard questionnaires bought in ‘off the shelf’. The general approach is to discover the details of what the job holder actually does and the knowledge, skills and abilities the person is drawing upon to carry out the job. This is not as simple as it might seem at first sight as many facets of any job may easily be overlooked. One approach is to look at what is involved in the job in terms of the following:

| – | planning, organising, decision making | |

| – | use of machines, tools, physical activity | |

| – | with other employees and customers | |

| – | working hours, physical conditions | |

For example, from the US, the Position Analysis Questionnaire seeks data on 194 job elements grouped into 27 dimensions and six categories, while the Management Position Description Questionnaire is a checklist of 208 items grouped into 15 sections related to concerns and responsibilities. The Work Profiling System has three overlapping tests, each consisting of 300 to 400 items analysed by computer to give a job description and profile of the ‘ideal’ recruit. However, as in much of HRM, there is need for a trade-off as these methods can be very time-consuming and expensive.

2.9.1.3 Interviews

Another method uses interviews, which have the same purpose as questionnaires and are often used in conjunction with them. They may be used to check questionnaire results and to discover further information about the content, context and requirements of jobs. Interviews may be held not just with job holders, but also with supervisors, subordinates, colleagues and customers.

2.9.1.4 Work diaries

Other methods include the keeping of work diaries, with details of tasks completed each day. Similarly, there can be critical incident reviews, where such events are logged and later reviewed.

2.9.1.5 Expert panels

If a job is new and therefore does not exist to be analysed, there is no job holder to investigate. So, a panel of experts is asked what the key tasks and skills of the future job are likely to be. The use of experts (either experienced workers or members of management) to assess job requirements is the system used most regularly in parts of Asia.

2.9.2 Job description

Where job analysis is used, the key elements in a job are outlined. These elements may then be written up as a statement – a job description – setting out what is involved in a job. A job description does not actually describe the kind of person who might be able to do the job; it is needed to develop a person specification. The possible contents of a job description are varied; in the West they often include the following:

![]() basic details (title, grade, location)

basic details (title, grade, location)

![]() reporting lines (which other jobs the post holder is responsible to/for)

reporting lines (which other jobs the post holder is responsible to/for)

In contrast, in some parts of Asia, such job descriptions as do exist are usually very limited in their content.

2.9.3 Person specification

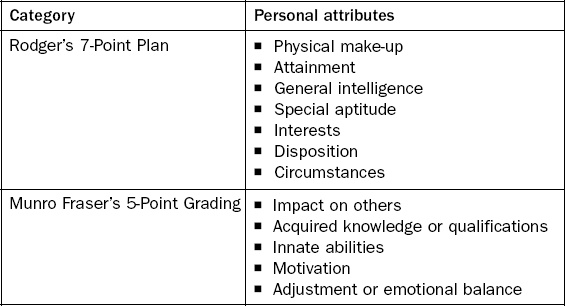

The information in the job description can be used to produce a person specification. This document lists and defines the attributes, often classified as either ‘essential’ or ‘desirable’, of a person who might be effective and content in the job. The person attributes can be grouped into major categories. Two of the most well known grouping methods are those by Rodger and by Munro Fraser, and are listed in Table 2.4.

In some parts of Asia, except within international organisations, person specifications are very general, and would probably be unacceptable in the West. For example, saying ‘attractive, female aged 18 to 21’ or ‘strong, healthy male aged 21 to 25’ would be considered discriminatory in the West.

In summary, organisations and managers aiming to resource HR in a systematic and standardised way should make efforts to:

![]() see the job and its requirements in all its dimensions

see the job and its requirements in all its dimensions

![]() compile personal attributes that are essential to effective performance

compile personal attributes that are essential to effective performance

![]() be aware of other factors that will impact on selection (such as political influences)

be aware of other factors that will impact on selection (such as political influences)

![]() list attributes that might improve performance as a basis to distinguish candidates

list attributes that might improve performance as a basis to distinguish candidates

![]() be aware of building in prejudices of ‘suitable’ candidates (i.e. race, gender, age, etc.)

be aware of building in prejudices of ‘suitable’ candidates (i.e. race, gender, age, etc.)

2.10 Sources and methods of recruitment and selection

How do organisations recruit the HR they need? There are several sources, divided into two groups: internal and external (as we saw in Chapter 1 and the ideas around different types of LM).

2.10.1 Internal methods

There are many common methods. They include the following.

2.10.1.1 Job bidding

This involves using current HR. Awareness of employment opportunities can be made by job posting via memos, emails, computerised bulletins, newsletters, staff vacancy notices, etc. As we will see later, in some parts of Asia existing HR are seen as the main source for new recruits and often a work unit or department will be dominated by people from particular places, even places a long distance from the location. Hence, Javanese are prominent in the Indonesian civil service, even in remote islands; Goanese or Keralites dominate sectors of Indian banks, and people from interior provinces of China make up most of the workers in manufacturing plants in Guangdong.

2.10.1.2 Promotion

Current HR may also be used as part of a promotion system and succession planning to fill vacancies. This includes the idea of being ‘groomed’, as the ‘natural heir’, or ‘crown prince’.

The above approaches involve employee transfers and are sometimes underpinned by a HR skills database, allowing identification of suitable existing talent. However, in parts of Asia the ‘database’ is actually a series of connections – what the Chinese call ‘guanxi’, the Arabs ‘wasta’, the Malays ‘orang delam’, the Japanese ‘kon’, the Koreans ‘inmaek and the Vietnamese ‘quan he’. Of course, if we think this a purely Asian phenomenon we should recall that the West has similar versions of the support network, such as the English ‘old school tie’.

2.10.1.3 Unsolicited applications

Unsolicited applications and speculative candidates are another source of recruits. This source is a feature of the recruitment process in parts of Asia. People desperately seeking work will try any means to follow up on the possibility of employment. The disruption to business activities resulting from trying to deal with countless applications reinforces the preference to rely on informal means of recruitment. Many thousands of candidates regularly apply for a few jobs with some employers. Mail services in much of Asia are not sufficiently reliable to be used by recruiters or candidates so personal visits are often necessary, in turn causing very large queues to form outside the premises of a potential employer.

2.10.1.4 Employee recommendations and contacts

To avoid applications by ‘unknown’ people, applications can be sought not by advertising but by letting it be known that certain vacancies are likely to arise. This is common in parts of Asia. Contacts will submit lists of candidates or will recommend specific individuals. Existing HR can encourage family, friends and contacts to apply for positions. This may even result in a payment from grateful employers. There are a variety of terms for such processes, including ‘kith and kin’, where jobs are seen as being handed down over generations within families. Western examples included Ford truck drivers in the UK.

One benefit of this process is that it may impose a form of ‘quality control’ check on new staff. Another benefit is to limit the need for the scope of checks (such as security vetting, etc.) for some jobs. However, one ‘cost’ of such a source is that the most suitable candidates might not be within the reach of the contacts. In addition, this process can replicate the characteristics of the existing workforce, and also therefore be discriminatory.

2.10.2 External methods

There are numerous external methods of recruitment. They include the following.

2.10.2.1 Referrals

These are registers kept by organisations of members seeking employment. Such organisations include trade unions, professional bodies and political parties.

As we have seen, however, some political organisations in parts of Asia may impose recruits on employers. So such organisations are rarely approached in recruitment matters because it is expected that they will have unsuitable recruits. However, if an influential person in the employer’s hierarchy wishes to build up ‘credit’ in their network (Chen, 2004), that person will suggest taking recruits from the political party, trade union, or even a Chinese clan group or an Indian caste.

2.10.2.2 Agencies

A variety of agencies may be considered for use in HR resourcing, and include central government provision of ‘labour exchanges’ or employment centres. Many countries have these but, because they may not be considered to be that effective, a range of private sector agencies have also arisen. These include outplacement consultants who provide help to enforced redundancies. Then there are selection consultants and temporary recruitment agencies, which can be used to reduce employer administration as they recruit and select for positions.

HR provision agencies (labour agents), which supply set numbers and types of HR, are popular in South West Asia, Malaysia and China, particularly in the construction, domestic service and mass production industries. This is often where the number rather than the quality of ‘labour’ is what the employer seeks.

For more senior positions another type of agency exists – the executive search consultant, or ‘headhunter’ as they are colloquially known. These organisations actively seek promising candidates through networks of similar senior managers and specialists. Headhunters are used for top jobs, particularly in India and China, where those with ability and connections are highly sought, but are less well established in countries such as Japan, where those in top jobs are reluctant to move employers, or Pakistan, where there is an established elite with such good connections that they do not need an intermediary to arrange an introduction to another top job.

The reputation of some Asian HR agencies is poor. When advertisements are placed with labour exchanges or HR suppliers the response is likely to be huge, creating much work for those seeking to fill posts. The HR suppliers often extract a fee from the candidates just to be placed on a register, and a higher fee if they are appointed to a job. Some countries, such as the Philippines, have legislated against candidates being required to pay a fee, but with little impact on the practice. Governments have used registration of agencies as a means of control, but malpractices are still widespread.

2.10.2.3 Educational institutions

Schools and universities with their career services can be used in HR resourcing as they can offer guidance and some testing. In some countries, such as South Korea and Japan, some employers have very close relationships with individual universities, departments and even individual faculties, and focus their attention and recruitment on specific sources. Such employers often fit their recruitment into the annual cycle of the completion of education.

2.10.2.4 Retirees

Retired workers can sometimes be considered as a possible source of recruits. In the past few years older workers in Singapore have become a focus of attention in the wake of publicity over the demographic ‘time bomb’ (which we noted earlier; see 2.6.2) with falling birth rates and increasing participation in education. This predicted a shortage of workers, particularly of younger people; so, with encouragement from the Singapore government, organisations have developed alternative HR resourcing strategies, including attracting and retaining those who would usually reach retirement age. In the remainder of Asia retirees are rarely sought unless they have retired from a role which had useful contacts, such as a senior civil service or military position, in which case they are offered a so-called ‘golden parachute’ (in Japanese amakudari, or ‘descent from heaven’) in a job where they can use connections with former colleagues or reap a reward for previous favours – a situation that is also found in the West.

2.10.2.5 Foreign workers

There is a long tradition of using this source of HR in various countries – for example, Turkish workers who were a source of HR in West Germany during the 1950s and 1960s. The former European colonial powers also made use of this source of worker, which included sending expatriates overseas to work and using specific nationalities in certain sectors/jobs and countries, such as Chinese laundry men, Indian rubber tappers, Malaysian and Sikh security guards in Hong Kong. Later these former colonial powers became the destination of labour. For example, Pakistanis moved to the UK to work in industrial mills while Bangladeshis moved to Europe to open ‘Indian’ restaurants.

This is a prevalent source of labour in parts of Asia, from the Indian construction workers in Dubai, the Myanmarese hotel workers in Thailand, the Bangladeshi petrol pump attendants, the Indonesian construction workers in Malaysia and widespread use of labour from the Philippines in several Asian countries. These workers provide flexibility (numerically) for their employer to cope with the peaks and troughs of workloads.

The employment of foreign workers raises many issues. These include those of a moral and ethical nature, such as exploiting poor workers who are forced to work in dangerous workplaces or who are mistreated financially and physically, as well as draining developing economies of skilled HR, particularly those in IT and health care.

2.10.2.6 E-recruitment

The use of the internet for recruitment purposes is a significant contemporary development in Europe and North America and has potential in India, China and South East Asia. This is in terms of both employers and candidates advertising on the web as well as through ‘cyber agencies’. Hunting for new jobs is one of the most popular online activities, as companies increasingly use electronic recruiting methods. The advantages of this method are cheapness and speed. Examples of jobs portals to assist in this e-recruitment, including some based in Asia, are shown in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5

Examples of e-recruitment sites

Western

www.moster.co.uk

A ‘career network’ (more than 24,000 UK jobs), easy to search for jobs, create a CV and set profiles for email notification of jobs that match your criteria. Has a career centre, ranging from discrimination to redundancy.

www.fish4jobs.co.uk

Simple – asks two basic questions: (1) What job? and (2) Where? It then delivers returns from 29,444 jobs listed. Individual channels, which include secretarial, marketing and construction, have trade tips, with a career centre, a ‘life coach’ and ‘legal doctor’ on hand to help.

www.workthing.com

Dominant in the public sector, education, media, charity and permanent IT positions, thanks to its links with the Guardian Media Group. After registration, you can set up a range of different profiles, add your CV for employers to download, and save interesting vacancies. Extras include email notification of suitable jobs (daily or instantly), a salary checker and help on making an immediate impression.

www.i-resign.com

This originally was an entertaining guide to quitting your job, which has expanded to become a fully fledged jobs portal. Old favourites remain, including Quit Countdown tips, resignation letter templates and the latest Big Quitters, but with a link to workthing.com.

www.jobsite.co.uk

One of the UK’s largest online agencies (e.g. 97,000 jobs advertised in one month) and with 35 industries covered. Along with the usual tools, you can create four different covering letters, how to write a CV and read the latest news on your sector.

www.planetrecruit.co.uk

The best option for agency-only jobs, which is all it deals with. No thrills and no extra content, but an impressive range of jobs is covered (100,000) with a fast search facility.

www.stepstone.co.uk

A large number of jobs – 62,000 in Europe and more in the US. Searching job categories follows the Yahoo model – clicking on a title brings up further options or search by job title. CV registration and tailored emails are available.

www.gis-a-job.com

High job total (85,000) with search engine by sectors.

www.jobs.ac.uk

Dominant for academic jobs. Allows a choice of types of job to receive regular direct postings.

Asian

www.4icj.com

Directory of top jobs, recruitment, employment and career sites in Asia.

www.classifiedpost.com.hk

South China Morning Post classified site; mostly jobs in Hong Kong, but some in China.

www.executiveaccess.com

Executive jobs in Asia.

www.expatriates.com/classifieds/china/jobs

A site for advice on working abroad with a classified jobs section as well as other adverts.

www.futurestep.com

A subsidiary of Korn Ferry, the executive search/headhunter firm.

http://jobchina.net

For bilingual candidates, especially for joint venture businesses and projects.

www.jobsabroad.com

Sections on China and other parts of Asia; mainly geared to teaching jobs.

www.jobsdb.com.hk

Chinese and Hong Kong headhunters mainly use this site.

www.jobstreet.com

One of the leading internet recruitment websites in the Asia-Pacific.

www.timesjobs.com

Linked to the widely circulated and popular Indian newspaper.

Major newspapers in the Asian region often put their classified adverts online and these can be accessed through the relevant website. As we note below, host country national and local employers rarely use advertisements, but international employers and recruitment agencies do tend to use this medium.

2.10.3 Advertising

Another method of recruiting involves advertising the position. A variety of media are available, from the more general to the more specific. This includes press, local and national television and radio, cinema and internet websites. Then there are posters, career exhibitions, conferences, brochures, videos and open days, which might be considered as methods of attracting recruits.

Advertisements placed in parts of Asia rarely provide much in the way of job information; the contents are likely to be limited to job title, a brief list of duties and the application process – which is usually to a PO box or an agent who will handle the response. Salary details and the identity of the ultimate employer are rarely included. The intermediaries can ‘mislay’ or divert applications so that the best candidates are not always presented to the employer. Standardised application forms are rare, so letters of application are presented in a wide variety of formats which can be difficult to consider in an objective manner and are not easily used by IT systems. Unsuccessful applicants are not usually contacted, partly to save costs but also to save face – it is considered better not to hear than to be rejected, and it also avoids having to discuss the reasons for rejection.

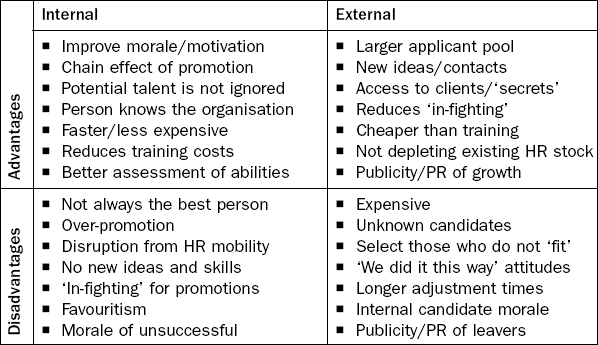

There are numerous methods of recruitment; each has its advantages and disadvantages. Some of these can be seen in Table 2.6. Most organisations follow a mixed strategy, although they differ substantially in their preference for internal and external recruitment. At one extreme are those that promote only from within. At the other extreme all posts are advertised externally, although existing employees may apply.

We can see an example of recruitment in practice in Asia in Text Box 2.4. This applies across a range of organisational types.

2.11 Selection

Once the closing date for applications, or at set intervals if there are no specific closing dates, is reached the selection of candidates can begin. This involves deciding whether applicants are suitable and then selecting ‘the best’, ideally by comparing and evaluating them against the yardstick of the job’s person specification – although we have seen that this often includes factors outside those in a formal person specification. The selection process may conclude with the deliberations of an appointing panel or committee, which reviews the information and reaches a judgement.

2.12 Methods

There are many selection methods, ranging from the short and simple to the longer and more complex.

2.12.1 Application forms

Although not often used in parts of Asia, application forms use standard questions to extract and record details of background, experience and personal data. This data is often simple, assessed subjectively and used to eliminate those applicants seen as unsuitable. There are many types of application form, varying in length and format. In those parts of Asia where letters of application are used more often than application forms, the lack of systematic presentation of data makes sifting much more haphazard than is the case where standard forms are used. An interesting aspect of this is the tendency of some organisations to request handwritten letters. This is seen in France, where graphology is considered to be a useful selection tool, although many non-French employers also judge candidates by the clarity and form of their handwriting.

2.12.2 References

References are requests for information about the candidate from past employers or staff of schools/colleges/universities with knowledge of the candidate’s character, and are used in support of other methods. References can be used to check the validity of statements made and to elicit additional information as well as to testify to the character or to offer professional opinions. In the West, legislation and employment case law has created an increasing ‘duty of care’ in providing references, with factual evidence and support needed for what is presented as an informed view of the candidate’s capability. References in some parts of Asia are usually informal and are used to establish a network or connection between the candidate and employer. The referee has given a commitment that the candidate is reputable and if he or she fails to work as expected, the referee loses face and so will be expected to put pressure on the recommended candidate to work well for the employer.

2.12.3 Interviews

A range of types and size of interview format also exists. Interview methods used (and misused) in Asia vary. This revolves around how many candidates are interviewed in an hour (15 to 20 would not be unusual in some countries), how long candidates wait before interview (most will be asked to arrive at the start of the working day even if they will not be interviewed for many hours), and how often review panels later add candidates who were not selected by interviewing panels. The possible interview methods include the following.

2.12.3.1 Unstructured

This is a commonly used format for interviews. It gives freedom to explore issues in some detail and depth in a free-ranging manner. This type of interview also allows interviewers to explore higher-level skills, such as conceptual reasoning. The use of this format, however, can make comparisons between candidates difficult and can produce complaints of unfairness as a result of candidates being asked different questions.

Yet, unstructured interviews are the main means of selection in parts of Asia. These interviews are often of very short duration and are used to support prior decisions or inclinations. In some areas of Asia the main purpose of an interview, and the wait before meeting the interviewer, is to establish the candidate’s role as a supplicant who will be privileged to work for the organisation. The employer rarely sets out to present an attractive image to enhance the recruitment process or to ‘sell’ the attractions of the job, aspects that may play a role in the West in tight labour markets or difficult to fill positions. Demonstrating the power in the relationship, rather than identifying capability, is the purpose of the interview. The candidate’s education and employment history is cursorily checked, and relationships and networks (to other employees and to political, kinship or social groups) are confirmed. Name-dropping (especially of prestigious educational facilities, prominent employers and important individuals) is an important part of the interview for middle-and senior-level jobs. Exceptions to the demeaning nature of selection will be made for high-prestige candidates whose status is far above those conducting the interview. Candidates who appear to be unusual, or who do not conform to the expected submissive manner, are likely to be rejected. In China, for example, candidates with ‘unlucky’ names will not even be selected for interview.

However, when interviews and other selection methods are demeaning, it is unlikely that the selected candidates will be motivated to work at their best for the employer. This outcome might be acceptable for workers on the most basic tasks, but not so for higher added-value work. In the medium and long term it is likely to be more effective to remove the demeaning interviews (and those who enjoy exercising power) and select employees who will enjoy being productive for the organisation.

2.12.3.2 Structured

These interview formats ask standard sets of questions and record responses, thus allowing the production of comparative data between candidates. This structure and process will assist in the required ‘discrimination’ between candidates for the final selection choice.

Structured interviews are rare in many parts of Asia and are used mainly by international employers, in particular those from the US who are used to an employment environment in which selection decisions are a potential source of litigation by aggrieved interviewees. Most local employers will be reluctant to interview all candidates in a standard way and managers will ignore instructions from HRM departments and managers to use such methods.

2.12.3.3 Mixed

These interview formats allow certain questions to be asked of all candidates. Other questions are specific to the particular individual. This format is usual in Singapore and Hong Kong, especially for managerial and professional positions. This style of interview is also the format which will, increasingly, be used by international organisations as management adapt to local conditions.

2.12.3.4 Individual and panel

The interview format may involve just a single interviewer. Alternatively, a small team, commonly three to five interviewers, may be used, usually with a mix of HRM staff and staff with knowledge of the specific requirements of the job to be filled. Recruitment for government jobs in parts of Asia, if not filled through quotas, will often use panel interviews, with a further review by a committee who will not actually meet the candidates. Panels and review committees are intended to remove bias, but often they introduce further levels of bias and ‘politics’ to the decision making.

2.12.3.5 Group

The applicant may be interviewed alone, which is more usual in the West. Alternatively, a number of candidates may be assessed simultaneously, particularly if large numbers are being considered for lower-level jobs. Labourers and factory workers are usually selected in this way by some Asian employers and by HR agencies. The group interviews sometimes are little more than the HRM equivalent of strolling around a market examining the goods available on all the stalls.

2.12.3.6 Telephone, video conferencing and email instant messaging interviews

This format can be used as a ‘screening’ mechanism (see Torrington et al., 2002) to make initial decisions on whether to move to a more time-consuming or costly stage in the recruitment process. Remote interviews are especially useful when it will be difficult to meet face to face because of time or distance constraints.

Although distances in some parts of Asia are huge, the lack of reliable long-distance communications and the preference to make candidates show willingness to meet employers’ requirements mean that telephone, video and instant messaging interviews are not often used. Some Asian employers are especially aware of the existence of ‘professional candidates’ who will substitute for the applicant, so employers in some countries make sure they identify the candidate accurately.

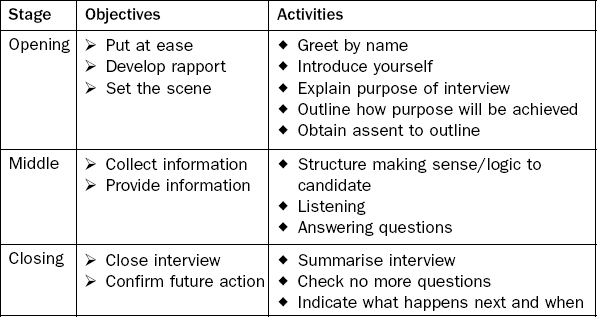

2.12.3.7 Conducting interviews

In terms of the conduct of interviews, potential employers and candidates need to be prepared, organised and on time (much of the following is just as relevant for performance management and appraisal interviews, see Chapter 4). The interview should be a two-way process: the candidate is also evaluating the organisation while the candidate is being evaluated. Furthermore, however difficult it may be for some managers, it is the applicant who should do most of the talking and this may require the development of active listening skills in the interviewer. In the West, techniques and skills in areas such as recording information during and at the end of each interview, and an awareness of the legal and ethical issues surrounding interviews, are required. As we have seen, in parts of Asia the interview is often not an opportunity for candidates to consider the employer so there is less of a two-way process and less pressure on interviewers to be organised, succinct and persuasive.

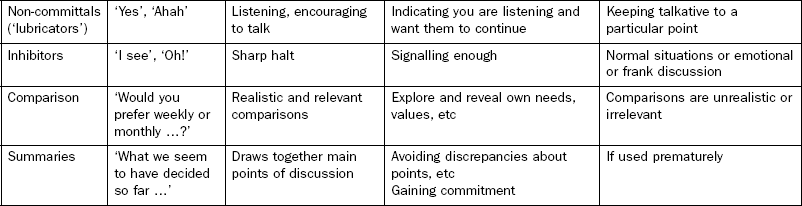

Some common perceptions, sequences, protocols and questions in respect of interviews can be noted and put into a pattern, as seen in Tables 2.7, 2.8 and 2.9. Despite the importance of interviews, readers may wish to reflect on how closely such a pattern has been followed in their experience. This experience could be as an interviewer or as an interviewee.

2.12.4 Limitations of the ‘classic trio’ resourcing methods

Even in the West, a long and consistent history of research has produced a list of problems with the ‘classic trio’ of employee resourcing methods. To recap, these three are: (a) application forms; (b) references (both of which present the ‘best case’ and are open to being ‘economical with the truth’); and (c) interviews (with biases, subjectivity, etc.).

There has been a growth of businesses that check the truthfulness of CV content owing to lack of honesty on the part of candidates. Companies may hire screening specialists, such as The Risk Advisory Group, to weed out untruthful CVs, although data protection and privacy rights of individuals need to be observed. It can also be a complex process if international background checks are required. Employers should be open about the nature of any discrepancies in CVs and allow them to be explained.

There were some high-profile cases in Singapore in 2007 when individuals were imprisoned for falsifying CVs and qualifications. Singapore may believe in rigorously enforcing its laws while in some other Asian countries this is not always the case. Even in terms of basic information, there are occasions in some parts of Asia when, without any intention to deceive, incorrect information is nevertheless given with regard to dates of birth, family and given names, all of which can vary with the result that different documents for the same individual may appear to be contradictory.

Given the enduring popularity (and use of the technique elsewhere, as in performance management and appraisals), it is essential to be mindful of some of the common biases in interviews.

There are many problems with interviews which revolve around the participants (interviewers and interviewees) themselves and the biases and effects that may result. Some of these problems can be seen in Table 2.10. One example of stereotyping and a common misconception that can influence selection is the belief that disabled job applicants will suffer higher levels of sickness absence than non-disabled people. In practice, the research and data does not support such a proposition. A similar issue arises with older workers, again not proven by the research.

Table 2.10

| Type | Characteristics/impacts |

| Non-verbal behaviour | Significant impact |

| Speed | Decisions made very quickly (within first few minutes) |

| Primacy | First impressions and information assimilated early on |

| Order of information | Favourable information early/later very influential |

| Halo and horns | Generalisation from one ‘outstanding’ characteristic (good or bad) |

| Expectancy | Positive/negative expectations formed from application form |

| Self-fulfilling prophecy | Questions designed to confirm initial impressions |

| Stereotyping | Includes comparisons with ideal applicant; implicit personality theory as a substitute for seeking specific information of applicant; characteristics are typical of members of particular group |

| Prototyping | Favour particular type of personality regardless of job-related factors |

| Contrast | Preceding applicants create context in which evaluation takes place |

| Negative information bias | Perceived negative points sought, given undue emphasis over more positive ones |

| Similar-to-me | Preference to those perceived as having similar background, history, personality |

| Personal liking | Whether or not personally like candidate |

| Information overload | Judgements formed on only a fraction of data |

| Fundamental attribution error | Actions caused by aspect of personality rather than simple response to events |

| Trait attribution | Past behaviour is good predictor of future behaviour (omits mediating influences and circumstances) |

| Temporal extension | Behaviour at interview is typical of general disposition |

Source: Adapted from Hakel (1982) and Taylor (1998)

Given the above, perhaps greater use of other selection methods should be encouraged. However, while they may be useful additions to the selection process, there are drawbacks with some of these other employee resourcing techniques that managers need to be wary of. Despite the weaknesses of the ‘classic trio’, some of the other methods are even less reliable. Indeed, it is disappointing that in some parts of Asia such unreliable methods (which include unstructured letters, unstructured interviews and group interviews) are still used.

2.12.5 Employment tests

Some methods that are used in the selection process have been shown to be better predictors of job performance than the ‘classic trio’. Employment tests seek to measure specific characteristics, abilities and behaviour of candidates. The benefits of these methods include the fact that the test results are numerical and statistical, so allowing direct comparison of candidates based on the same criteria and producing explicit and specific results – although they may need to be interpreted and analysed, particularly in the case of tests of personal attributes. These tests provide ‘hard’ data which can be evaluated for their predictive usefulness in later years (i.e. comparing predicted with actual performance). Several tests to assist in employee resourcing are available; they include the following.

2.12.5.1 Ability tests

These tests involve a range of simulations or events. Some are paper or computer screen tests of numerical or verbal reasoning and other abilities. There can be work scenarios and actual tasks, such as being given a piece of real or simulated work to complete or a team problemsolving exercise. In several Asian countries the military use such tests as part of the initial assessment of recruits. Asian airlines, such as Cathay Pacific, use aircraft simulators to test candidates, who already have some flying experience, for aircrew jobs.

2.12.5.2 Psychometric tests of occupational personality

Occupational personality tests attempt to determine if the candidate has the ‘right’ kind of ‘personality’ for a job. In the UK a survey in 2000 found that 54 per cent of companies from a broad sweep of industries said they used such tests (The Financial Times, 2001). In the West the use of psychological tests varies by job level. For example, while used for 20 per cent of manual positions, this figure rose to between 70 and 80 per cent for management posts and 90 per cent for graduate entry positions (Newell and Shackleton, 1994).

This type of test is still rare in parts of Asia, although some international and national firms produce and administer tests in Singapore, Malaysia, India and China.

2.12.5.3 Assessment centres

A more reliable selection method is the assessment centre with its battery of tests. These tests compare candidates’ performance in simulated problems, with focused or behavioural event interviews which seek a deep understanding of candidates in relation to the role envisaged for them. There can be a range of tests; indeed the number of techniques used is an advantage. The use of several trained assessors is essential. The assessors enable the pooling of tests and assessors’ results. Tests can include, for instance, ‘in-basket’ simulations where candidates are asked to process and take action on an accumulation of memos, reports and letters, or team exercises involving building a small tower or bridge. Others tests include leaderless group discussions when a group response to a question is required. Individual presentations may also be used in the exercise, as may assigned leadership tasks.

Major employers in the West use assessment centres as they are recognised as better predictors than the ‘classic trio’ and other selection methods. In parts of Asia only a limited number of military organisations and international organisations (such as banks and oil companies) use assessment centres on a regular basis.

There are several drawbacks with tests. These can be seen in Table 2.11 and also below.

Table 2.11

| Disadvantage | Characteristics |

| Responses | Faked for ‘desirable’ scores (especially where same tests used/practised) |

| Temporary factors | Produce variable results, e.g. because of anxiety, illness, etc. |

| Ethnocentric | USA (white, middle class, male) based comparisons as ‘norm’ and reference |

| Meaningful | Accuracy (Stagner’s research) |

A classic piece of research carried out by Stagner in 1958 (reported in Jackson, 1996) provides a further warning against the use of personality tests, even when they are used in the same culture as that in which they were developed. In Stagner’s research, some 68 managers completed a personality questionnaire. At the end, each manager was presented with a written profile summarising the main characteristics of their personalities. The managers then completed a further questionnaire asking how accurate they believed their profile to be. Some 50 per cent ranked their profile overall as being ‘amazingly accurate’ and a further 40 per cent as ‘rather good’. However, the researchers had tricked the managers by giving them all the same faked personality profile to assess, instead of genuine summaries of their own personalities. This shows that tests can appear to be a great deal more accurate and meaningful than they actually are.

2.12.6 Problems with using employment tests in Asia

A major problem with using tests developed outside Asia is that the tests may have unforeseen cultural expectations with them, and so may be biased against groups in Asia. For example, in some Asian educational systems students are taught to remember the ‘right’ answer, whereas most Western ability tests ask those being tested to find the ‘right’ answer without guidance from a teacher.

The occupational personality tests developed in the West are also based on different cultures. These will, for example, assume that classic theories, such as Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs or Cattell’s (1946) theories of personality are universal, whereas most societies have different views of personal needs and personality (see Smith and Bond, 1998; Shweder, 2003). The external norm groups used for comparison in ability and occupational personality are also different from those in the West and almost no test providers have yet developed suitable norm groups for Asia. One example of the norm group issue was an Asian bank that used UK-developed ability tests to examine candidates for teller jobs. The norm groups from the UK were based on secondary school leavers, whereas in much of Asia tellers are university graduates. The candidates tested therefore produced scores much higher than the UK norms and the advice from the testing firm was that the people had too much ability and would soon be bored in the teller jobs. In the event, however, the candidates made effective and long-serving tellers.

We can see an example of selection practice in Asia in Text Box 2.5. This is seen across a range of organisational types.

2.13 Recruitment and selection in practice

Variations in employee resourcing are noted in Text Box 2.6.

However, selection may be more ad hoc and reactive than the earlier examples indicate. The level, sophistication, time and cost that organisations actually apply to employee resourcing vary. As we have seen, in parts of Asia the selection process is very rudimentary. The type of selection device used and the elaborateness of the procedures employed do vary according to the perceived importance of the job to the organisation. For example:

![]() Tests and interviews are often sufficient for school leavers applying for entry level jobs.

Tests and interviews are often sufficient for school leavers applying for entry level jobs.

![]() Higher-level occupations may demand more personal and exhaustive approaches.

Higher-level occupations may demand more personal and exhaustive approaches.

![]() The use of psychological tests varies according to job level.

The use of psychological tests varies according to job level.

We can also see some interesting examples in Asian countries, some of which are set out in Text Boxes 2.7, 2.8 and 2.9. The case studies in Appendix 3 also provide examples.

2.14 Conclusion

In this chapter we have covered the initial key area of HRM – employee resourcing. This was in terms of HRP and the commensurate recruitment and selection process that this may require. The predictions are that HRP will be of limited use in some parts of Asia. This is partly because an unstated assumption in HRP is that the future has continuity with the past. The influences of environmental volatility, applicability for small firms and rapidly developing Asian economies reduce the use of HRP in some Asian countries.

However, to be useful, HRP should be seen not as a highly precise technique, but as a loose collection of ideas and tools which can be applied as necessary to the individual needs and circumstances of a particular organisation.

In terms of recruitment and selection, several key points were made. Recruitment methods can apply to existing and new HR and vary depending on the HR approach of the organisation (the flexible firm, and so on), and the level and types of HR sought and the normal practices in the country concerned. Furthermore, a set of questions quickly arises. These include the following.

![]() What is required to perform the job?

What is required to perform the job?

![]() What selection techniques have predictive validity?

What selection techniques have predictive validity?

![]() Is there a significant relationship between a predictor (for example, the interview rating of applicants) and subsequent successful performance in a job?

Is there a significant relationship between a predictor (for example, the interview rating of applicants) and subsequent successful performance in a job?

![]() Are these reliable (for example, consistency of the measure over time)?

Are these reliable (for example, consistency of the measure over time)?

No selection process provides a complete, accurate prediction of performance as jobs change and people develop, and techniques of assessment and measurement are imperfect. Nevertheless, a variety of methods can be used to compensate for prejudice or unreliability from a single source of assessment.