Employee relations

5.1 Introduction

This chapter is concerned with the area of employee relations. Here, unlike some other commentators, we do not make a hard distinction between the terms industrial relations (IR) and employee relations, which we take to include all aspects of work and the work environment. The area of IR and then employee relations were key areas feeding into the development of personnel management, and then into HRM. The field has critical impacts on HRM, through the political process as well as employer and employee organisations (such as trade unions), and includes labour market changes and legislation. In parts of Asia politics and employee relations are often strongly linked. This discussion forms the first half of this chapter, dealing with its early development, definitions, a system, strategy, perspectives, partnership and the future.

In the West (especially in the European Union), a key aspect of the employee relations area – not least because it is seen to be both a ‘cause’ and a ‘cure’ for ‘poor’ employee relations – is employee involvement. A spectrum of practices is often lumped under the rubric of this elastic concept, ranging from industrial democracy through to financial participation. A more contemporary guise is the idea of workplace partnerships. However, the use of employee involvement as a solution to help in business and management problems often comes too late in the HRM strategy and processes, with it being ad hoc, used merely as a ‘bolt on’ and some sort of organisational ‘life belt’. This area forms the second major part of this chapter, where employee involvement is examined in terms of forms and practices with the related issues that these raise.

5.2 Overview

Employee relations as a subject frequently arouses very mixed reactions. Why is this? For some commentators attitudes are influenced by a range of factors, which include ‘frames of reference’ and ‘perspectives’ in employee relations. Trying to interpret employee relations issues and events, especially disputes, in terms of the ‘facts’ of the situation to arrive at an explanation of the causes is not easy. Yet, surely ‘the facts speak for themselves’? With sufficiently close attention given to collecting detailed information can we not come across some objective explanations? We will look at these issues in the first part of this overview.

The origin of employee relations is in IR, with its antecedents arising in the late nineteenth century ‘labour problem’, with its ‘Two Faces’. On the one hand, there was labour militancy, conflict and economic disruption; on the other hand, there were issues of poor pay and poor working conditions. The best ‘solution’ to this problem was seen by many as collective bargaining, to which IR became closely linked. The IR area remained marked by pragmatism and its scope largely reflected the practical concerns of management, public policy and governments. From the 1950s to the 1980s the area became almost synonymous with trade unions and strife. Managing this strife was a major and time-consuming concern of personnel specialists and line managers, as well as governments as, for example, in South Korea and Japan.

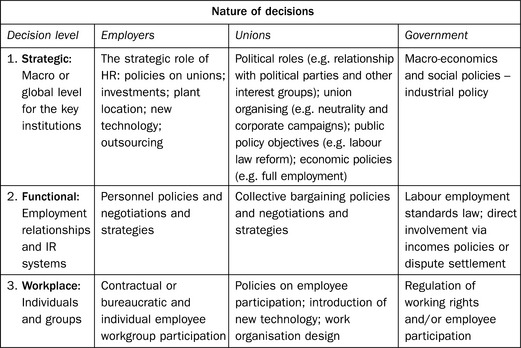

Drawing on a wide variety of theories and data from economics, history, sociology, law, politics and organisational behaviour, employee relations is concerned with all aspects of the employment relationship. It was argued that in every country there was an employee relations ‘system’ involving three groups or parties: workers and their organisations; employers, managers and their organisations; government and agencies concerned with work (see Dunlop, 1959 and Figure 5.1). Every system creates a complex set of rules to govern the workplace; these rules, and the context in which they operate, will be considered in more detail later in this chapter (see 5.4.1 and 5.4.2).

Figure 5.1 The ER system Source: Dunlop (1958)

The idea of ‘good’ and ‘harmonious’ employee relations is often proposed as ‘normal’ and the key to success. This can be seen in some of the ‘Asian Tiger’ economies. Why does this harmony seem so elusive and the subject of debate? If we look at employee relations in Asia there is great diversity in structures and practices. The role of employee organisations as one group in the employee relations system has been hotly debated, especially in the US. Nevertheless, even in American HRM models (see Chapter 1), trade unions are considered by many to be both ‘stakeholders’ and ‘situational factors’. In the same framework, employee influence is given as a ‘HRM policy choice’ while ‘laws’ are another situational factor. Indeed, the idea of employee involvement, and more recently ideas of ‘partnership’ with labour/trade unions, is not new. The ideas of HRM processes and procedures to reduce or resolve conflict are also of long standing.

We can see some of the issues regarding employee relations and disputes in the Asian example in Text Box 5.1.

Among other issues, there may be disagreements in employee relations. If there are disagreements, how can we attempt to prevent and resolve them?

Some of the issues and processes in this area are illustrated by the examples in Text Box 5.2.

There are examples of dispute resolution processes around the world. These include the US, Australia and Switzerland (see Salamon, 2000) as well as Asia. Some interesting examples are provided in Text Boxes 5.3 and 5.4 covering the resolution of disputes in China and Vietnam.

5.3 Employee relations

We can trace the antecedence and development of employee relations, which could be said to have existed ever since people interacted in the labour process.

5.3.1 Definitions

Some definitions of IR are narrow – as, for example, those of the influential early pioneers of the topic, such as Flanders (1970) and others. For these writers, IR was about the institutions of job regulation and the rules governing employment. Thus, IR was seen as being about job regulation and collective bargaining, and often narrow sectors and workers – industrial, male, manual workers and their organisations, trade unions. Yet, this reduced IR to the study of formal bargaining structures and procedures, which is somewhat limiting.

In contrast, for other commentators, the starting point for IR was the ‘exchange relationship’ – the buying and selling of ‘labour’. In particular, the basic disparity of bargaining strength between the ‘buyer’ and ‘seller’ of labour actually makes conflict inevitable. These commentators, for example, considered that IR was the process of control over work relations (Hyman, 1975). Yet, while this is interesting and it broadens out the field, employee relations covers more than just this: it involves the study of both structures and actions.

However, there are broader views of employee relations, which view it as being concerned with all aspects of the employment relationship. It includes the study of individuals, groups and their unions and associations, employers and their organisations, and the environment in which these parties interact. It is this idea of organisations and environments which we turn to next.

5.4 Concept of a ‘system’

In every country an employee relations system, a subsystem of the economic and political system, exists. This involves the following three groups or parties (see Figure 5.1 in section 5.2).

![]() Workers and their organisations

Workers and their organisations

![]() Employers, managers and their organisations

Employers, managers and their organisations

![]() Government and agencies concerned with the workplace and work community

Government and agencies concerned with the workplace and work community

Furthermore, the concept of an employee relations system can be applied at different levels, as follows.

![]() National (different countries)

National (different countries)

![]() Industry (different sectors of production or services)

Industry (different sectors of production or services)

![]() Group, firm and plant (particularly given the importance of international corporations)

Group, firm and plant (particularly given the importance of international corporations)

5.4.1 Rules

Every employee relations system creates a complex system of rules to govern the workplace and work community. These rules may take a variety of forms – for example, agreements, statutes, custom and practice – but their essential character is to define the status of the parties and to govern their conduct. These rules are fundamentally of two kinds:

1. Procedural – the methods and procedures to be used, such as those involved in settling disputes.

2. Substantive – dealing with, for example, rates of wages, hours of work, and so on.

The system’s rules may be created in a variety of ways – through laws, collective bargaining, or imposed unilaterally by one of the parties.

5.4.2 Context

The parties and the system do not operate in a vacuum but within an environmental context comprising the following aspects.

![]() Political and legal factors – i.e. the power relationships and status of the parties

Political and legal factors – i.e. the power relationships and status of the parties

![]() Economic factors – in particular, labour markets and product markets

Economic factors – in particular, labour markets and product markets

![]() Social factors – including culture and values

Social factors – including culture and values

![]() Technological factors – i.e. methods and resources applied to production

Technological factors – i.e. methods and resources applied to production

If rules are the output of the system, the input to the system is the value and objectives of the three parties. The subject matter of employee relations, therefore, involves the three parties of the system and their organisation, objectives, relationships and interactions within the environment in which they operate.

While a classic piece of work, Dunlop’s (1959) writing attracted much criticism, some of which stems from his own time and place of 1950s American pluralism. Dunlop argued, for example, that in each employee relations system there was an underlying, shared ideology (of consensus) which was expected to lead to stability in the system. However, the emphasis on stability and consensus makes it difficult for the model to explain dynamic change. Thus, Dunlop’s work was criticised for being too static, overly conservative, ignorant of behavioural factors, and more concerned with solving, rather than seeking, the sources of conflict.

5.5 Strategic choice

Criticisms of Dunlop led some writers to build on his approach. They introduced into the area the important concept of ‘strategic choice’ and the idea of applying it at three levels (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2 Strategic choice in industrial relations Source: Kochan et al. (1984)

Strategic

This level comprises the strategies, values, structures, and so on of the parties. Here we may ask questions such as how business strategy affects employee relations. For example, we might compare a business strategy that emphasises product differentiation and innovation against one seeking to minimise labour costs (see the earlier points in Chapter 1). In much of Asia, especially in South Asia, politics and employee relations are closely linked. Political groups use employee relations as a means of putting pressure on governments or opposition. In Asia we can compare the focus on labour reducing costs in countries such as Vietnam with the deliberate policy of driving up the cost of labour to encourage higher added-value jobs, such as in Singapore.

Functional

This level represents the actual process and results of contract negotiation. The discussion of strikes, bargaining power and wage determination feature prominently here. An Asian example of the functional level is the Japanese ‘shunto’ annual pay negotiations which take the form of ritual posturing between employers’ and employees’ representatives.

Workplace

This level illustrates the activities in which employees, their supervisors and their union representatives engage in administering the labour contract and adjust to changing circumstances and new problems on a daily basis. Here there are issues such as managing conflict, motivation, participation and supervision of individual workers, as well as the structuring of work into jobs, groups or teams. The use of ex-military HR managers in countries such as China and Pakistan, with their supposed experience of managing people, shows the importance of managing the day-to-day workplace issues.

5.5.1 Goals and expectations

Importantly, this model is driven by the goals and expectations that people have of work. How people go about achieving their goals is through the organisational structures and processes. It is through these structures and processes that parties interact and make choices that, together with forces in their environment, determine the extent to which their goals are met.

Without a safety net of wealth or government support, some Asians work to gain the means of survival, including basic goods and services, for themselves and the family. For example, the provision of organisation-supplied accommodation by employers – such as the Indian railways, Chinese SOEs, Malaysian utility companies, South Korean manufacturers in Malaysia and contractors in the GCC – gives a needed source of shelter but comes at the risk that the of loss of a job (or involvement in an industrial dispute) will lead to loss of that shelter as well as loss of income.

5.5.2 Options and choice

This model emphasises the range of options that management, labour and government have in responding to environmental changes (such as increased competition or changes in technology). Although the environment is vitally important there is also, it is suggested, a degree of choice at all three levels.

Another useful addition is the idea of strategic choice and employee relations decisions being of a ‘third order’ (Purcell, 1987). This presents employee relations as ‘downstream’ of other strategies for organisations. This can be seen in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3 Three levels of strategic decision making Source: Purcell (1987)

5.6 Frames of reference

An important development for employee relations concerned the work and ideas on the fundamental perspectives taken by people on the basic structures and roles of organisations.

Within an organisation, are we ‘all in it together’, part of a team harmoniously pulling in the same direction with similar ambitions, desires, and so on? If so, how do we explain some of the conflicts and disagreements in relation to work? The seminal work of Fox (1966) explained that two views may be taken of the enterprise and managerial conceptions of its authority structure, i.e. on the nature, function and legitimacy of trade unions. These are as follows.

5.6.1 Unitarist perspective

In the unitarist perspective the organisation has a unified authority structure with common objectives and values – that is, there is one source of authority and focus of loyalty: ‘a team’. Thus, it can be argued here that people:

strive jointly towards a common objective, each pulling his weight to the best of his ability. Each accepts his place and his function gladly, following the leadership of the one so appointed. There are no oppositionary groups or factions, and therefore no rival leaders within the team? Nor are there any outside it; the team stands alone, its members owing allegiance to their own leaders but to no others.

(Fox, 1966: 3)

This unitarist perspective is a common view of some Asian managers and government authorities. However, the role of trade unions and employee conflict in parts of Asia suggests this is less the perspective of all actors in the system.

5.6.2 Pluralist perspective

In the pluralist perspective the organisation is seen to consist of a coalition of individuals with diverse objectives and values. Here it can be argued that:

In place of a corporate unity reflected in a single focus of authority and loyalty, we have to accept the existence of rival sources of leadership and authority.

(Fox, 1966: 4)

So, organisations are made up of sectional groups with divergent interests, and this limits the degree of common purpose. For example, management has to balance various interests, which include shareholders, directors, customers and employees.

This pluralist perspective is less common in some parts of Asia among managers and government where rival thought is considered by some to be much more threatening than it is in the West (Harry and Nakajima, 2007). However, the existence and role of trade unions and conflict in parts of Asia, such as South Korea and Malaysia, suggests that pluralism is a perspective held by others.

In addition to these views, it is worth noting here another perspective – a radical view, which is a modification of Marxist analysis. This perspective denies that there can be any common interest in the employment relationship. Maoists in parts of India and Nepal and the Communist Party of North Korea maintain this perspective while the Communist Party in China has tended to ignore the issue during its pragmatic dealings with the factors impacting on economic growth. This radical view maintains that only the leadership of the Communist Party can determine the ‘correct’ path in employee relations and there is no need for intervention by other participants.

With the pluralistic view, it follows that some conflict is inherent in the very nature of employee relations. It is, therefore, as important for management to accept that some conflict of interest is inevitable as it is for unions and employees to accept that there are some common interests – in particular, contribution to the survival and success of the organisation. With the growing acceptance in the West, after the 1950s, of this sort of proposition, collective bargaining became increasingly considered by many as the best method to resolve these differences of interest.

The core thread running through employee relations is that labour is more than a commodity to be exchanged in the open competitive market and more than a set of ‘human resources’ to be allocated to serve the goals of the firm (Blyton and Turnbull, 1998). Rather, because workers bring their own goals, expectations and aspirations to the workplace, employee relations must also be concerned with how the policies governing employee relations, and the work itself, affects workers and their interests, as well as the interests of the firm and the larger society (Blyton and Turnbull, 1998). Nevertheless, conflicts should be limited in scope and frequency since the parties’ goals are interdependent and common and at least some are shared. The essence of effective employee relations is, therefore, one in which the parties successfully resolve issues arising from their conflicting interests and successfully pursue joint gains in cases where they share common interests.

5.7 Individualism versus collectivism

There are other useful perspectives to consider in employee relations. One such approach is to view employee relations in terms of individualism versus collectivism and its variants. By individualism we mean the degree to which management asserts the individual nature of the relationship with employees within employee relations. By collectivism we mean the amount of collective focus in the relationships within employee relations. This view also allows the production of a set of employee relations regimes at societal level.

Furthermore, not only are there these different perspectives in employee relations, but their prevalence over time, and across different countries, has varied. This can be usefully seen if we make a broad brush coverage of history over the last two hundred years of industrialisation in order to locate developments and ground the more contemporary situation. We present such views next.

5.7.1 Liberal individualism/laissez faire

Along with industrialisation in the West during the nineteenth century was the idea of liberal individualism or laissez faire. With this it was believed that everything should be determined by the free play of markets. Thus, employment contracts were freely entered into by relatively equal people capable of pursuing their own best interests. Any combination of workers or employers would adversely affect this free market mechanism, which, if left to itself, would ensure the greatest possible good for all. The anti-combination feelings were strongest in the US where the government acted to prevent or reduce combinations of workers or employers aimed at protecting ‘customers’ from monopolies of labour or production. While this is an historical model, it has contemporary relevance, particularly in terms of World Trade Organisation values concerning free markets.

5.7.2 Liberal collectivism

From the late nineteenth century liberal collectivism developed. This was ‘liberal’ in the sense that the role of the state was limited. Simultaneously, this was ‘collective’ in the sense that parties were free to organise and engage in collective bargaining.

5.7.3 Corporatism

After the Second World War, and particularly following the1960s, there developed a greater degree of government involvement and co-operation between the employee relations parties. This was seen in various examples – which included incomes policies and the establishment of tripartite mechanisms involving government, employer and employee representatives – in a number of countries. From the late 1970s such approaches declined. On the one side opposition grew to the view that unrepresentative trade union ‘barons’, not elected politicians, were now running countries in ‘shady deals’ with politicians. On the other side some wanted a return to ‘free’ collective bargaining and the end of trade union use in macro-economic policy, as in keeping inflation under control via incomes policies. Some countries have maintained elements of corporatism – for instance, the Scandinavian system, versions in South Korea from the 1990s and the succession of social partnership agreements in Ireland and Australia since the 1980s (see Salamon, 2000).

5.7.4 Individualism/neo-laissez faire

From the 1980s such corporatism was weakened with a revival, not so much of liberal collectivism, but essentially of individualism or neo-laissez faire. This was seen in the UK, but less so in some other countries, especially in Europe. Pro-trade union support and legislation was repealed and replaced by anti-trade union laws in a ‘step-by-step’ approach which whittled away union strengths in the UK. By 1997 the UK employee relations legal terrain was dramatically different from that of the earlier period.

5.7.5 Social democratic individualism

In the UK, after 1997 and the return of the Labour Party to government, there was a re-evaluation in terms of employee relations. On the one hand there has been much criticism that Labour was all ‘style over substance’ and that little has changed. This is seemingly supported by Labour’s pronouncements that the previous Labour legislation would not be fundamentally overturned and that the UK benefited from a flexible labour market, which it needed to maintain. Yet, on the other hand, there is increasing vocal criticism by business interests of the so-called over-regulation of the economy, part of which concerns the regulation of employment matters. The post-2010 election situation in the UK is still in its early stages.

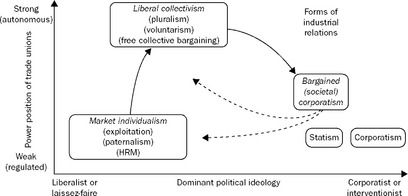

5.7.6 Government approaches

There are several models that use dimensions of varying trade union power and political ideology. The models, historically developed in the West, have relevance in contemporary situations – for example, liberal individualism in the past and in the 1980s in the UK, corporatism from 1945 to the 1980s in the UK, in Scandinavia since the 1930s, in post-war Japan, and now developing some aspects in South Korea and other Asian countries. We give an example of one such model in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4 Governmental approaches to employee relations Source: Salamon (2000)

5.8 Partnership

Following Labour’s 1997 election victory, as mentioned above, there was renewed interest in ideas of so-called workplace ‘partnership’ and deals. These were trumpeted as the way forward for employee relations, especially in the context of ‘New Labour’ in the UK. A range of employers and trade unions signed such agreements, and they received endorsement and encouragement from senior politicians. There had been some developments during the previous 18 years whereby some businesses and management had tried to change and recast ‘traditional’ employee relations. This was labelled by some commentators as ‘The New IR’.

The ‘New IR’ changes involved reconfiguring trade union recognition and bargaining arrangements in order to try to obtain ‘simplification’. For instance, in companies where multiple unions had been recognised, there were attempts to move to either ‘single table bargaining’ (with all the different unions bargaining together) or ‘single union recognition’ (with commensurate de-recognition of the other unions). If the organisation or particular operation was new, a single union-only recognition was offered from the start. This recognised union would then represent everyone in the company, in a similar way to some Asian enterprise unions, such as those in Japan.

We present some Asian examples (Japan, South Korea and Malaysia) of trade unions, types and structures in Text Boxes 5.5, 5.6 and 5.7.

Japan has built much of the success of its manufacturing sector on the partnership between management and unions. In Japan one union represents all in the company as an enterprise union. This recognition of a specific trade union could well be preceded by what was called a ‘beauty contest’ for management to pick its favoured union. One of the most well known examples of the latter, in the UK, was Nissan’s recognition of the then AEEU at its new Sunderland factory on a ‘greenfield’ (newly industrial) site.

A key aspect of such single union deals was often the idea of what came to be labelled ‘no strike agreements’, along with compulsory and maybe ‘pendulum’ arbitration (see the points on dispute resolution earlier in this chapter). However, not only are such agreements impossible to enforce, they are better seen as ‘strike last agreements’. For instance, how would an employer actually prevent employees from walking away from the workplace or all claiming to be ‘sick’ at the same time? Ideas of pendulum arbitration have come from the US. Pendulum arbitration was taken as a possible method to prevent the ‘chilling’ of negotiations that occurred as sides simply waited to go to arbitration, which would then force parties to make realistic demands and offers and reduce extreme cases. These tactics were often used to try to maximise or minimise awards in the all-too- common eventuality that the result was to split competing demands down the middle. In contrast, with pendulum arbitration the most reasonable cases (to attract the pendulum) would be presented by both sides because ‘split’ awards were not allowed. It was either the whole of one offer or the whole of the other that had to be decided on by arbitration. So, employer and employee positions would now aim to be the most reasonable in order to attract the arbitrator’s decision (the pendulum).

However, there are classic problems with these processes. As with other forms of third party intervention, both sides could use this process to opt out of any responsibility for the outcomes. Both sides can lose control over the situation. It means the sides are presented as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. Yet, negotiations are rarely about a single issue, but are a mixed and tradable set of issues. These issues create tensions and problems for arbitration and single trade unions.

Thus, there are difficult issues. The diversity in this area can also be seen in countries such as Japan, China and India. Japan stresses long-term stability and shared prosperity with low (by Western standards) differences in pay between the top and the bottom of organisations. Theoretical partnerships in Chinese SOEs should mean that all are ‘working for the common good’ with apparently low differentials in pay (but certainly high differentials in terms of benefits and status) in the expectation of long-term prosperity. Indian politics and economics were, for many years, dominated by socialist ideology so that employers found it difficult to encourage change or greater productivity and tended to hide profits, along with the real level of executive pay and benefits, mainly in the ‘black’ economy. Trade union officials were often encouraged, discreetly, to take the employer’s side, while some officials would pursue their own political ends without seeking to protect their own union members.

We present some Asian examples of employee relations systems in Text Boxes 5.8 to 5.11. These cover China, Vietnam, India and the Philippines.

5.9 The future of employee relations

The area of employee relations has evolved, as it has always done, partly driven by business and management, as well as government, concerns. As long as there is a labour process, there will be employee relations and the need to understand its history and traditions and what drives those involved. Long-term predictions of the radical change of employee relations, with the demise of conflict and trade unions, have been unfounded. For example, trade unions and political parties, as in India, have formed close relationships that work well when the particular parties are in power. Political parties, when in government, support their trade union partners but when they are in opposition the favoured trade unions are used against the government – irrespective of the harm this might do to the interests of the trade union members, their employers and the country. As Asia creates more knowledge, and as employees are seen more as human capital rather than just factory ‘hands’, employee relations will evolve, but with an Asian character.

One of the persistent interests of employee relations, both in terms of a ‘cause’ and ‘cure’, is employee involvement – a flexible and heterogeneous term and concept that can cover a wide range of practices, each with radically different implications. This has become an even more ‘hot topic’, not least driven by practices, ideas and regulations from the US and Europe in Asian suppliers, as was well demonstrated by Litvin (2003) in describing consumer group pressure on Asian work practices.

5.10 Employee involvement

The importance of employee involvement to employee relations, and to HRM more generally, is often made. It is seen as trying to create a sense of belonging and commitment through information about the organisation and its environment. A key management task is to decide if, and how, to share information because important information may be used by employees, such as in negotiations to share with competitors, customers or regulators, among others. Yet, a lack of action by management itself actually amounts to a decision not to share information, demonstrating a lack of trust in their employees. It is primarily a management responsibility to create the conditions and establish the policies and practices to promote effective employee involvement and trust.

In parts of Asia there is a reluctance to share information as this is seen as reducing the power of the source of the information – the owners and managers. Subordinates are expected to provide information, usually positive information, to supervisors, but this is not a mutual exchange, so little reliable information will be passed back. Supervisors are unwilling to share power and authority and expect obedience and loyalty from staff. Staff on their part expect to be told what to do and do not wish to take responsibility for their bosses’ tasks, fearing that they would be forced to take the blame when things go wrong. Some Asians often refer to this as upward delegation of decisions.

There has been a whole range of reasons offered for the interest in employee involvement, some of which are shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1

Reasons for interest in employee involvement

| Factor | Aspects |

| Efficiency | Improve organisationally |

| Change | Make more acceptable |

| Commitment | Enhance |

| Learning | From employee knowledge and skills |

| Social | Increased aspirations, reduce alienation |

| Control | Redefine managerial authority |

It is this great diversity of reasons for the interest in employee involvement that partly gives rise to a heterogeneous concept, exacerbated by terms such as ‘involvement’ and ‘participation’ used interchangeably, despite the gaps in their implications, including differing levels, power sharing, and so on. Therefore, we need to make some broad distinctions from the start. With this in mind, we can usefully consider the concept of employee involvement within a framework, as demonstrated in Figures 5.5 and 5.6.

Figure 5.5 Employee involvement framework Source: Salamon (2000)

Figure 5.6 Dimensions of employee involvement Source: Bratton and Gold (1999)

These types of framework usefully and clearly indicate that there are variations in the area of employee involvement. This is in terms of several dimensions, which include the following.

These frameworks also usefully display the differences in form and type. As Salaman (2000: 374) put it:

It is the nature and quality of the process of interaction which determines the extent or depth to which employees (individually, in groups or through their representatives) are allowed and able to contribute to and influence organisational decisions (whether operational or strategic).

This may range from only informing by management through consultation to negotiation and finally co-determination (equal influence in both setting the agenda as well as deciding the outcome or organisational decision making).

Participation is primarily a philosophy, not a particular institutional form … Therefore, it can take place at any time and in any organisational framework so long as management is genuinely and unreservedly prepared to share responsibility for the decision- making process with employees and/or their representatives.

Nevertheless, to help understanding, some further details will be illustrative.

5.11 Forms of employee involvement

There is vast range of examples of employee involvement, which have some specific and common advantages and disadvantages.

5.11.1 Communication

Communication is at the basic level of employee involvement. It can be both one-way and two-way.

5.11.1.1 One-way communication

With one-way communication, information is given by one party to another. The HRM objective of one-way communication is to try to ensure that all HR know and understand what they and others in the organisation are doing and why. This is the most common means of communication throughout much of Asia. There is a huge variety of practices here; they are widespread and include notice boards, letters, staff newspapers and magazines, employee reports, in-company videos, performance appraisals and oral presentations. One of the more recently reported systems is ‘team briefing’.

Team briefing

This is a system of communication that is often operated by line management. It is based on leaders and their teams getting together in groups on a regular basis. Information is ‘cascaded’ down through organisational levels and management tiers through supervisors to the lowest levels of the organisation. Part of the team briefing normally contains ‘core’ information relating to corporate issues. This is supplemented by local news at each stage. Some Asian organisations – for example, in the Kuwait oil sector – use team briefings as a means of communication so that messages can be reported quickly, in a standard format and, hopefully, accurately.

Team briefing has its share of both benefits and problems. They include those shown in Table 5.2.

5.11.1.2 Two-way communication

Unlike simple information giving, two-way communication in HRM attempts to give subordinates some ‘voice’ and provide feedback to both parties. Again, there is a very wide variety of methods and practices here, which include the following.

‘Speak-Out/Up’ or feedback programmes

Here people can telephone or write (by email or letter), in confidence, to a company representative to raise concerns. The initiators are usually guaranteed a response within a specified period.

Open-door programmes

This type of programme enables employees to see management who are not their immediate supervisors. Examples are rare in Asia, except for those with influence or connections (‘guanxi in China, ‘wasta’ in the Arab lands, ‘giri’ or ‘con’ in Japan, ‘inmaek’ in South Korea, ‘orang delam’ in Malaysia, ‘quan he’ in Vietnam) which can be used to short-cut organisational hierarchies. In theory, bosses in Asia may operate an opendoor policy, but those who enter the open door know that they risk drawing attention to themselves and that they probably will upset their immediate supervisor. Mis-steps through the open door can be seriously career limiting, unless the employee has good connections.

‘Walking the floor’

Senior executives physically and visibly walk though the shopfloor and offices. This behaviour is to be seen and also to listen. In parts of Asia, the being seen is far more important than the listening, although this method is regularly used by Asian managers who wish to be seen as part of the organisation’s community and who value the opportunity to demonstrate a ‘common touch’. It is also used as a means of keeping middle management under pressure in case senior management discover that there are problems that have not been disclosed to them.

Sensing groups

In this system management meet periodically with small random samples of staff. This allows management not only to communicate company policies and goals to the groups, but also to hear employee concerns and suggestions. Trade unions and political or social networks are the more usual form of sensing groups in parts of Asia, but these groups often have agendas other than organisational success and may not necessarily represent the interests of employees.

Task forces

These groups, often of junior managers and employees, can be commissioned on various areas and concerns – for example, to review specific policies or processes or be asked to suggest improvements. Such practices are used with success in Japan, in particular.

Employee attitude surveys

These represent a more systematic means of feedback. This type of survey has spread in use and can be undertaken by specialists or in-house staff. At first sight this method seems more concerned with measuring commitment than involvement. In-house surveys especially are viewed with suspicion in some of Asia as it is doubted whether confidentiality and anonymity will be respected. However, the benefits of surveys are numerous so some Asian organisations favour this method of obtaining information from the workforce – especially as the expectation is that employees will not give negative opinions. The benefits of surveys include the following

Suggestion schemes

Suggestion schemes are often seen as being applicable only to large manufacturing firms and manual workers, but they are also to be found in the service sector and among white collar staff – for example, in banks, airlines and retailing. HR are invited to submit ideas to improve aspects of organisational performance for which they are often rewarded. The reward is usually an award (cash or benefit) of which there can be several types. These can include the following.

![]() Encouragement – for effort in making suggestions even if they are not implemented

Encouragement – for effort in making suggestions even if they are not implemented

![]() Valued – for leading to clearly quantified savings (fixed amount or percentage of savings)

Valued – for leading to clearly quantified savings (fixed amount or percentage of savings)

![]() Special – for savings not easily identified (for example, health and safety matters)

Special – for savings not easily identified (for example, health and safety matters)

Suggestion schemes have their own benefits and problems, which can be seen in Table 5.3.

5.11.2 Task and work groups

Employee involvement can also occur at a different level and in a different form in the task and work group. These employee involvement occurrences have a long history, deriving from the well known ‘Human Relations’ experiments in the US in the 1920s. Ideas of job enlargement and enrichment developed from the 1960s, introducing elements of responsibility into tasks. The development in such matters was led by some Scandinavian organisations. Examples of such forms include the following.

Autonomous work groups

In 1972 Saab Scania’s factory abolished the classic, Fordist mass production, single assembly line moving at fixed rates past workers. In its place were six separate assembly areas and workers divided work amongst themselves without management direction. Similar experiments occurred at Volvo in its Kalmar and Uddevalla factories.

In Asia, subcontractors are used as autonomous work groups so that firms such as Toyota send specialist work to small firms with whom they have a long-term and close relationship, treating the firms as closely linked to the larger enterprise. Japanese firms are also keen on project-based teams working together with few formal distinctions between the team members, of different seniority levels, or their roles outside the team. However, the levels of employee autonomy, and hence involvement via this route, is debatable. Indeed, autonomous work groups are rare in parts of Asia.

Quality circles (QCs)

Typically these groups are small, with six to twelve members led by a supervisor or team leader in the area; they are ‘voluntary’, meeting regularly within paid work time (although meetings can be held during ‘leisure’ time). The QCs identify, select and analyse work-related problems, collect data, present findings and propose solutions intended for approval by management, which are then implemented. After 1945 came the development, in Japan, of this American idea - set out earlier by people such as Deming and Juran. By the late 1980s, Japan had over 10 million workers in QCs. The common requirements for such QCs include the following.

![]() Management are convinced of the benefits, giving long-term commitment and resources

Management are convinced of the benefits, giving long-term commitment and resources

![]() Involvement of middle managers

Involvement of middle managers

![]() Facilitator for administration and development of ideas

Facilitator for administration and development of ideas

There are several benefits and problems with QCs, as noted in Table 5.4. Total Quality Management (TQM) then emerged, partly as an alternative means of addressing quality issues. TQM is a more integrated approach to quality matters, with ‘harder’ objectives, which are work-related and performance-led, rather than concerned with employee involvement.

Table 5.4

Benefits of and problems with quality circles

| Benefits | Problems |

| ✕ Sustaining, have short life/high failure | |

| ✕ Time/expenses in running, training, disruption, etc. | |

| ✕ Challenge notions of authority, criticisms of management | |

| ✕ Disinterest - middle management allocated responsibility, but denied authority (own agenda; not obliged to follow priorities) |

Team working

Team working, in its present guise, has its origins in the UK in practices at organisations such as Japanese companies like Komatsu, Hitachi, Nissan, and especially Toyota. Since the 1990s this form of organising work has become more prevalent in other sectors.

Empowerment

Empowerment became fashionable from the 1980s, although it was linked to earlier movements such as the Quality of Working Life approach in the 1970s. In essence, empowerment is about providing the opportunities and structures (and, of course, the work culture) so that employees can contribute to the organisation. The onus is on management to ‘empower’ staff. This empowerment is individual and direct involvement in work. A range of benefits flow from this method of organising, including the need for less direct management and supervisory control, with greater employee autonomy, albeit within bounds set by management.

5.11.3 Financial

For some commentators, employees also obtain involvement through particular financial arrangements. This is not, in fact, a new idea (see Chapter 3 on employee rewards). Indeed, there are examples of such financial arrangements from the early nineteenth century in the West and in a few Asian companies, such as Tata in India. Nevertheless, the rise in popularity in the West has occurred since the early 1980s, encouraged by governments through favourable tax legislation, and has been followed by a modest application of the systems in Asian organisations undergoing privatisation, especially in South and South West Asia, and by ‘buying out’ the jobs of workers in SOEs in China. The types of financial participation include the following.

5.11.4 Success of employee involvement

Several important elements in the success of employee involvement have been identified, and can be seen in Table 5.5.

Table 5.5

Important elements in the success and failure of employee involvement

| Elements | Reasons/Characteristics |

5.11.5 International variations in employee involvement

There are widespread variations globally in the meaning and practice of employee involvement (see earlier frameworks). This includes the ideas of industrial democracy, workers on the board, co-determination and works councils.

This is also the case across Asia. We provide an example of one form in South Korea in Text Box 5.12.

5.12 Conclusion

The area of employee relations remains as important, but as changeable, as ever. While the foci of the area have shifted – partly reflective of the practical concerns of business, management and governments – the ideas of a model of a system of actors who have different perspectives remains a useful aid and framework in the understanding of employee relations. The different participants may vary in their relative influence and power, but their interactions and perspectives remain crucial, not only to the functioning of an economy, but also to its competitiveness and the types of production which prosper.

The area of employee involvement is a diverse and elastic concept, seemingly allowing everyone to support it. Involvement also has a range of benefits for organisations and employees. Some of the key ideas and practices are not particularly new, although employee relations fashions do come and go, as witnessed by ideas of ‘industrial democracy’ in the 1970s versus ‘empowerment’ more recently. These ideas and practices vary throughout Asia, yet their various forms have radical differences in implications for management and businesses.

References

ACFTU, Chinese trade unions’ safeguarding of the legitimate rights and interests of workers and staff members, 2005. (2004) Blue Paper, 12 September 2005. Available at (accessed 23 August 2006). http://www.sa8000.org.cn/NewsCenter/1235.html

Alas, R. (ed.) Implementation of Change in Chinese Organisations. Oxford: Chandos.

Benson, J., Debroux, P., Yuasa, M., Zhu, Y. Flexibility and labour management: Chinese manufacturing enterprises in the 1990s. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2000; 11(2):183–196.

Bishop, D., Reed, L. Practical guidelines for intervening, selecting and challenging party-appointed arbitrators in international commercial arbitration. Arbitration International. 1998; 14(4):395–406.

Bitonio, B.E.R., Labor flexibility and workers representation in The Philippines. An initial version of this article was presented at the 5th Asian Regional Congress of the International Industrial Relations Association, 2004. [Seoul, Korea, in June 2004].

Bitonio, B. The changing nature of work in Asia: The Philippines. In: Burgess J., Connell J., eds. Globalisation and Work in Asia. Oxford: Chandos; 2007:129–150.

Blyton, P., Turnbull, P. The Dynamics of Employee Relations. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 1998.

Bratton, J., Gold, J. Human Resource Management Theory and Practice. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 1999.

Bronfenbrenner, K., Friedman, S., Hurd, R., Oswald, R., Seeber, R. Organizing to Win: New Research on Union Strategies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1998.

Burgess, J. and Connell, J. (eds) Globalisation and Work in Asia. Oxford: Chandos.

Cai, Y.S. The resistance of Chinese laid-off workers in the reform period. China Quarterly. 2002; 170:327–344.

Chang, K. On enacting legislation on unfair labour practices. Social Sciences in China [Zhongguo Shehui Kexue]. 2000; 2000(5):71–82.

Chen, D.R. Chinese Firms between Hierarchy and Market: The Contract Management Responsibility System in China. New York: St Martin’s Press; 1995.

Chen, F. Economic Transition and Political Legitimacy in PostMao China: Ideology and Reform. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1995.

Chen, F. Subsistence crises, managerial corruption and labour protests in China. China Journal. 2000; 44:41–63.

Chen, M.S., Chan, A. Employee and union inputs into occupational health and safety measures in Chinese factories. Social Science and Medicine. 2004; 58:1231–1245.

Cheng, Y.Y. The development of labour disputes and the regulation of industrial relations in China. The International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations. 2004; 20(2):277–295.

Chibber, V. Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2003.

Chibber, V. From class compromise to class accommodation: Labor’s incorporation into the Indian political economy. In: Ray R., Katzenstein M., eds. Social Movements in India: Poverty, Power and Politics. Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, 2005.

China Statistical Yearbook, (various issues), Beijing: China Statistics Press.

China Labour Statistical Yearbooks (various years) Beijing: China Statistics Press.

Choi, Y.J. Managerial styles, workforce composition and labour unrest: East Asian-invested enterprises in China. Comparative Sociology. 2003; 2(2):321–354.

CIPD, Employee relations, 2005. Available at (accessed 25 February 2005). http://www.cipd.co.uk/mandq/standards/prac/sgpd/emprel.htm

Clarke, S., Lee, C.H. The significance of tripartite consultation in China. Asia Pacific Business Review. 2002; 9(2):61–80.

Clarke, S., Lee, C.H., Li, Q. Collective consultation and industrial relations in China. British Journal of Industrial Relations. 2004; 42(2):235–254.

Confederation of Indian Industry, Northern Region, Driving growth through reform: A comparative analysis of labour practices in select northern region states, 2004.

Cooke, W.N., Noble, D.S. Industrial relations systems and US foreign direct investment abroad. British Journal of Industrial Relations. 1998; 36(4):581–609.

Dunlop, J., Industrial Relations Systems, 1958. [and 1959 New York: Holt].

Fahey, S. Changing labour relations. In: Kerkvliet B.J.T., ed. Dilemmas of Development: Vietnam Update 1994. Canberra: Australia National University Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, 1995.

Fernandez, L., It’s hard to stay together. Sunday Star. 1993. [7 November: 18].

Fernandez, L. More expected from the MTUC. The Star. 1997. [25 January].

Flanders, A. Management and Unions: Theory and Reform of Industrial Relations. London: Faber and Faber; 1970.

Fox, A., Industrial Sociology and Industrial Relations. Royal Commission Research. 1966. [Paper No.3, London: HMSO].

Fox, J.B., Donohue, J.M., Wu, J.P. The arbitration of labour disputes in China today: Definition and implications. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal. 2005; 17(1):19–29.

Hagglund, G., Provis, C. The conciliation step of the unfair dismissal process in South Australia. Labour Studies Journal. 2005; 29(4):65–86.

Harry, W.E., Nakajima, C. Foreigners’ ethnocentric policies in the Asia Pacific region. Management Revue. 2007; 18:4.

Hisano, K. Employment in transition: Changes in Japan since the 1980s. In: Burgess J., Connell J., eds. Globalisation and Work in Asia. Oxford: Chandos; 2007:275–294.

Huo, Y.P., von Glinow, M.A. On transplanting human resource practices to China: A culture-driven approach. International Journal of Manpower. 1995; 16(9):3–15.

Hyman, R. Industrial Relations: A Marxist Introduction. London: Macmillan; 1975.

India Labour Bureau. Indian Labour Yearbook. Delhi: Ministry of Labour, Government of India; 2004.

Jomo, K.S. U-Turn? Malaysian Economic Development Policy after 1990. Townsville, QLD: James Cook University; 1994.

Kennerly, J.A. Arbitration: Cases in Industrial Relations. Pitman; 1994.

Kochan, T., McKersie, R., Capelli, P. Strategic choice and industrial relations theory. Winter: Industrial Relations; 1984.

Krishnamurthi, S. Commercial’s Commentary on Trade Unions Act 1926 as amended by Trade Unions (Amendment) Act 2001. Delhi: Commercial Law Publishers; 2002.

Kuruvilla, S., Venkataratnam, C.S. Economic development and industrial relations: The case of south and southeast Asia. Industrial Relations Journal. 1996; 27(1):9–23.

Labour Law of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam 1994 (Vietnam).

Labourer, The [Ngu.ò.i Lao Dô. ng], 1 January 2002.

Lee, C.K. Pathways of labour insurgency. In: Perry E., Selden M., eds. Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Lee, M.B. Korea. In: Rothman M., Briscoe D., Nacamulli R., eds. Industrial Relations Around the World. Berlin: de Gruyter; 1993:245–269.

Leong, C.H. ‘Late industrialization along with democratic politics in Malaysia’, unpublished doctoral thesis. Harvard University; 1991.

Littler, C., Palmer, G. Communist and capitalist trade unionism: Comparisons and contrasts. In: Pravda A., Ruble B.A., eds. Trade Unions in Communist States. Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1986.

Litvin, D. Empires of Profit. New York: Texere; 2003.

Maimunah, A. Malaysian Industrial Relations and Employment Law, 4th edn. Kuala Lumpur: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

Martin, R.M. Trade Unionism: Purposes and Forms. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1989.

McLaren, D.E. Party-appointed vs list-appointed arbitrators: A comparison. Journal of International Arbitration. 2003; 20(3):233–245.

McNamara, D. Market and Society in Korea: Interest, Institution and the Textile Industry. London: Routledge; 2002.

MHR. Statistical Summary of Labour and Human Resource. http://www.mohr.gov.my/mohr_key.php, 2006. [(accessed 30 June 2006) available at].

Mo, J. Probing labour arbitration in China. Journal of International Arbitration. 2000; 17(5):19–83.

Mok, Ka-ho, Wong, L., Lee, G.O.M. The challenges of global capitalism: Unemployment and state workers’ reactions and responses in post-reform China. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2002; 13(3):399–415.

Morris, J., Sheehan, J., Hassard, J. From dependency to defiance? Work-unit relationships in China’s state enterprise reforms. Journal of Management Studies. 2001; 38(5):697–717.

Nasscom-g. (2005) http://www.bpo.nasscom.org/artdisplay.aspx?cat_id=563 (downloaded on 27 November 2005).

Nasscom-h. (2005) http://www.bpo.nasscom.org/download/Maharashtra%20ITeSPolicy2003.pdf(downloaded 23 December).

Nasscom-i. (2005) http://www.bpo.nasscom.org/download/AP%20ITES%20Policy.pdf (downloaded on 23 December).

Ng, S.H., Warner, M. China’s Trade Unions and Management. London and New York: Macmillan/St Martin’s Press; 1998.

NMP. 9th Malaysia Plan 2006–2010. Putrajaya: Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department; 2006.

Nørlund, I., Chan, A. Vietnamese and Chinese labour regimes: On the road to divergence. The China Journal. 1998; 40:173–197.

NUBE (National Union of Bank Employees), History, 2006. available at (accessed 20 October 2006). http://www.nube.org.my/history.asp

Purcell, J. Mapping management styles in employee relations. Journal of Management Studies. 1987; 24(5):534–548.

Ramasamy, N., Rowley, C. Trade unions in Malaysia: Complexity of a state-employer system. In: Benson J., Zhu Y., eds. Trade Unions in Asia. London: Routledge; 2008:121–139.

Ramaswamy, E.A. Worker Consciousness and Trade Union Response. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1988.

Ratnam, V. Globalization and Labour-Management Relations: Dynamics of Change. New Delhi: Sage; 2001.

Rowley, C. Alan Fox. In: Witzel M., ed. Biographical Dictionary of Management. Bristol: Thoemmes Press; 2001:325–327.

Rowley, C. Hugh Clegg. In: Witzel M., ed. Biographical Dictionary of Management. Bristol: Thoemmes Press; 2001:168–170.

Rowley, C. Conciliation. In: Redman T., Wilkinson A., eds. The Informed Student Guide to HRM. London: Thomson Learning; 2002:39.

Rowley, C. Mediation. In: Redman T., Wilkinson A., eds. The Informed Student Guide to HRM. London: Thomson Learning; 2002:157.

Rowley, C. Allan Flanders. In: Warner M., ed. The International Encyclopaedia of Business and Management. London: Thomson Learning; 2002:2036–2041.

Rowley, C. Do we need processes of dispute settlement in managing today? Effective Executive Magazine. XII(4), 2009. [April].

Rowley, C., Bhopal, M. The ethnic factor in state-labour relations: The case of Malaysia. Capital and Class. 2006; 88:87–116.

Rowley, C., Poon, I. HRM best practices and transfer to the Asia Pacific region. In: Wankel C., ed. 21st Century Management. US: Sage; 2008:209–220.

Rowley, C., Yoo, K.S. Trade unions in South Korea: Transition towards corporatism. In: Benson J., Zhu Y., eds. Trade Unions in Asia. London: Routledge; 2008:43–62.

Salamon, M. Industrial Relations: Theory and Practice. Harlow: Pearson Education; 2000.

Selvarani, P., Abas, M. Airline’s union officials under probe. Malay Mail. 2004. [31 January].

Sheehan, J. Chinese Workers: A New History. London and New York: Routledge; 1998.

Shen, J. Analysis of changing industrial relations in China. The International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations. 2006; 26(3):347–368.

Shen, J. Labour Disputes and their Resolution in China. Oxford: Chandos; 2007.

SHMTUC (Shanghai Municipal Trade Union Council). Lao Dong Guang Xi Diao Cha (Labour Relations Survey). Shanghai: Shanghai Municipal Trade Union Council; 2002. [(in Chinese)].

Sicat, G.P. What it will take to reform RP’s labor market?. Manila: Paper presented at the National Tripartite Policy Conference on Wages and Productivity; 2005.

Sodhi, J.S., Plowman, D. Economic Change and Industrial Relations: India and Australia. Nedlands, WA: Scholastic Press Australia; 2001.

Song, L.B., Zhao, J., Li, H. Approaches to the revision of the 1994 Arbitration Act of the People’s Republic of China. Journal of International Arbitration. 2003; 20(2):169–189.

Sun, The, NUBE may face legal action, says Fong, 2003. [12 August].

Taylor, B. Trade unions and social capital in transitional communist states: The case of China. Policy Sciences. 2000; 33:341–354.

Thireau, I., Hua, L.S. The moral universe of aggrieved Chinese workers: Workers’ appeals to arbitration committees and letters and visits offices. The China Journal. 2003; 50:83–103.

Thite, M., Russell, B. India and business process outsourcing. In: Burgess J., Connell J., eds. Globalisation and Work in Asia. Oxford: Chandos; 2007:67–92.

Todd, P., Peetz, D. Malaysian industrial relations at century’s turn: Vision 2020 or a spectre of the past? International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2001; 12(8):1365–1382.

Vo, A. The Transformation of HRM and IR in Vietnam. Oxford: Chandos; 2009.

Walder, A.G. Communist Neo-traditionalism: An Introductory Essay. Berkeley, CA: University of Chicago Press; 1986.

Wu, M.A. Industrial Relations Law of Malaysia, 3rd edn. Kuala Lumpur: Longman; 2006.

Yu, X.M. ‘State-intervened legal activism: Case studies of labor unrest at foreign-invested enterprises in South China’, Hong Kong University, University Service Center for Chinese Studies. http://www.usc.cuhk.edu.hk/wk_wzdetails.asp?id=3299, 2005. [(accessed 12 May 2005) Available at].

Zhu, Y., Warner, M. Changing Chinese employment relations since WTO accession. Personnel Review. 2005; 34(3):354–369.