Employee rewards

3.1 Introduction

We have now covered the initial aspects of HRM – resourcing the organisation with people. This can involve planning requirements for HR and recruiting and selecting them. One factor that critically impacts on these aspects of HRM is that of employee rewards and its management (see White and Druker, 2000). For instance, HR resourcing difficulties, including the dimensions of attraction and retention, may be linked back to employee rewards. Rewards retain their importance for a range of reasons and reward practices attract widespread media, political and public attention, especially in cases where rewards seem to be too low or too high. These issues have been brought to the attention of an even wider audience with the fall-out from the post-2008 global financial crisis as the high reward practices in sectors such as banking have come under fresh scrutiny.

Later in this chapter we discuss rewards in terms of their link to ‘performance’, and how, and to what extent, these aspects can be built into HRM systems. This is also linked to ideas of HR flexibility and the flexible firm model (see Chapter 1 at 1.7.2.2). Indeed, while some forms of such performance-linked reward systems are not particularly new, there is a continuing interest in them from a range of bodies – not just businesses and other employers, but also governments and policy makers. For example, in parts of Asia the public sector offers low rewards but, at least until recently, it offered job security. As governments struggle to reduce bureaucracy and the number of their public sector employees through privatisation, technology and simplification or codification of laws, the combination of low rewards and low job security creates serious economic and political problems which could even threaten the existence of some governments (Harry, 2007). For example, the impact of high rates of youth unemployment and low pay in the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) countries led to the use of recent increases in oil wealth to award substantial pay increases to citizens in the public sector (around 70 per cent in the case of the United Arab Emirates).

The types of reward system and some of the related methods and issues will be examined in this chapter. Rewards are also one of those areas and issues that display wide variation in practice and in acceptance of certain levels, as well as internationally and comparatively. We will look at some of these practices and issues.

3.2 Overview

Employee rewards retain their relevance and importance for HRM for several reasons, which include the following.

1. Rewards interact with many other aspects of HRM – for instance, employee resourcing, such as attracting and retaining HR, and employee relations, including the involvement of trade unions in negotiations and disputes involving rewards.

2. Rewards also impact on other areas, such as organisational performance, as well as having a role in driving and integrating with strategy and reinforcing values (see Wilson, 2001) and enhancing employee motivation and commitment. Indeed, for some commentators, the decline of career systems and commensurate employee commitment is also linked to rewards, with the need now to focus more on broadly defined rewards to elicit employee commitment. Job security in Asia is declining, especially in the public and semi-public sectors; for example, the ‘iron rice bowl’ (guaranteed employment) of China has been broken. Even some Japanese firms, well known for lifetime employment, have found ways to dispose of surplus labour – even to the extent of removing all job responsibilities and letting staff sit and do nothing except look out of the window (known as ‘madogiwazoku’, the ‘window gazing clan’) in the hope that they will be humiliated into resigning. Throughout Asia there are moves to reduce the number of employees who have security of employment and rely on temporary or ‘contingent’ employees, or those from other countries or other regions who have little expectation of being able to claim employment rights.

3. Overall, employee rewards are composed of numerous elements. Putting these together as a ‘rewards package’ can range from a simple to a more complex mix of ‘intrinsic’ and ‘extrinsic’ rewards. A rewards package can include pay, benefits, promotion, praise, longterm security of employment, opportunities for development and training, for instance, with ‘generalised investments’ (see Galunic and Weeks, 2001). A possible framework by which to assess an organisation’s portfolio of rewards could be made up of four types:

The above can be seen in the two dimensions of: ‘cash versus non-cash’; and ‘all employees versus some employees’ – that is, differentiated by performance (Wilson, 2001).

4. Rewards can form a large part of the cost basis of a business and may even be a method of competing between employers. This reward role does vary, even between countries, where some employers offer higher pay than employers in neighbouring countries – for example, Singapore and Malaysia, India and Nepal, or Hong Kong and neighbouring Chinese provinces such as Guangdong, where costs from higher pay would be expected to lead to businesses moving to cheaper neighbours. However, many employers believe that the higher wage costs are worthwhile as the HR are more productive or are capable of undertaking greater added value work which justifies the higher costs. For those organisations operating in highly competitive markets exposed to foreign competition, minimisation of labour costs could be critical to their survival. This has been an important factor in the Asian ‘tiger’ economies of South East Asia and is now important in Vietnam, China and India. However, this may be less the case in other sectors, such as private services, were there are often non-tradable (non-exportable) jobs. For instance, if the price of a haircut goes up because of increases in wages (imposed by a statutory minimum wage, for example), what would customers do since all other businesses would be paying the same rate and therefore charging the same price? Customers may try to reduce the number of visits for a haircut, but they are unlikely to go overseas for the service. Businesses may then even be encouraged to attempt to compete on the basis of quality rather than (low) cost if wages are standardised amongst all in the sector.

5. The area of rewards also attracts much public, institutional, government and media attention and comment. Debates around both the bottom (i.e. national minimum wage or extremely low pay for migrant workers) and top (i.e. top management and investment bankers’ remuneration) of the rewards spectrum retain their salience and high profile. This area has become far more widely exposed with the post-2008 global financial crisis resulting in a plethora of examples of seemingly indefensible rewards practices, especially in the West.

6. Employee rewards remain highly varied internationally. For senior managers there are expectations of very high rewards and large differentials from employees in the US, whereas in other countries, such as India and Japan, this large differential is not so widely expected. There are also ideas of seniority-based pay in some countries, such as Japan and South Korea. Then there is the harmonised annual round of reward increases, such as ‘shunto’ (the ‘spring livelihood offensive’) in Japan, held every year since 1955, although this practice is now under some stress (The Economist, 2003).

One aspect of rewards is an increasing, albeit not new, focus on setting levels by linking rewards to contribution and ‘performance’. This is by various links to different performances in diverse schemes. Ideas of adding greater performance (or ‘variable’ or ‘at risk’) aspects to rewards can create a volatile employee relations situation. The maxim ‘what gets measured gets done’ has relevance here as people may do what is rewarded and not what is needed.

Performance-based systems require several elements to assist in their success. These include:

![]() a clear understanding of measures, goals or standards and actions that people need to take

a clear understanding of measures, goals or standards and actions that people need to take

![]() challenging but achievable goals (Wilson, 2001)

challenging but achievable goals (Wilson, 2001)

![]() a short, robust and explicit link between performance and reward

a short, robust and explicit link between performance and reward

![]() must ‘fit’ with prevailing personal, organisational and national cultures

must ‘fit’ with prevailing personal, organisational and national cultures

You can look at the above and complete the questions set out in Case Study 3.1 below. Also, Hille (2008) provides the interesting example of Chungwha Telecom in Taiwan, which made changes to its rewards packages and the role of incentives and shares in that, while Guerra and Chung (2008) note issues surrounding executive pay.

3.3 Rewards and integration

The links between business strategy and integration with HRM (as we discussed earlier in Chapter 1 at 1.7) can be seen here in reward elements. These linkages can be explicit, as seen in Table 3.1. Thus, there can be integrated reward systems, driven by business strategy. However, it does still need to be remembered that contingency theory (also discussed in Chapter 1 at 1.5.1) is important in rewards. In particular, variations can stem from the following factors: (a) organisational strategies and cultures need different reward strategies; (b) the usefulness of reward strategies and practices varies according to context, and (c) reward practices affect people differently.

Table 3.1

| Business strategy | Reward strategy |

| Added-value by improving motivation and commitment | Introduce/improve PRP (individual, team, gain-sharing) |

| Added-value by improving performance and productivity | Introduce/improve PRP and performance management |

| Competitive advantage by value by developing and using distinctive core competencies | Introduce competence-related pay |

| Competitive advantage by technological development | Introduce competence-related or skill-based pay |

| Competitive advantage by delivering better value and quality | Recognise/reward for meeting/exceeding customer service and quality standards |

| Competitive advantage by developing capacity to respond quickly and flexibly to opportunities | Provide rewards for multi-skilling and job flexibility Develop flexible pay structures (broad banding) |

| Competitive advantage by attracting, developing and retaining high quality HR | Ensure pay rates are competitive Reward for developing competencies and careers in broad-banded pay structure |

Source: Adapted from Armstrong (1999)

3.4 Types of reward

Employee rewards can come in many varieties.

The broad aspects of rewards can be seen as comprising the elements shown in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2

| Aspects of rewards | Examples |

| Money | Salary, bonus and incentives, expenses |

| Benefits | Pension, cars, housing, insurance, leave, medical facilities |

| Work | Challenge, autonomy, environment |

| Development | Training, personal development, employability, job security |

People require rewards for the services they provide for the organisation. In taking a job a person must work and forsake time which could be occupied with other activities. Therefore, organisations ‘compensate’ for the time lost and the efforts put in by individuals to carry out the tasks and duties of a job. This is why US organisations, in particular, refer to pay systems as ‘compensation’. Compensation comes in two main forms: intrinsic and extrinsic.

3.4.1 Intrinsic rewards

These rewards relate to the inner satisfactions experienced in carrying out the tasks and duties of a job. These satisfactions may be small or large, depending on factors such as the degree of interest in the work, conditions, opportunities and recognition. Intrinsic rewards may not usually be sufficient to induce someone to take a job and remain in it, although people may accept lesser extrinsic reward if the intrinsic satisfactions of a job are obvious and substantial.

Charity workers, such as those based in Malaysia and India, for example, may chose a vocation which pays less than they could expect from other career choices. Throughout Asia, working for a prestigious employer or a government department with status is considered to be a valuable intrinsic reward.

3.4.2 Extrinsic rewards

These have two major aspects: first, pay, which can be received in the form of wages, salary, bonuses, commissions, and so on, and, secondly, benefits, which can be other rewards that have a notional monetary value but are not paid in cash. There is a vast array of examples here, ranging from housing, car or transport, pension/provident fund, loans, insurance, medical facilities, meals, recreational and child care services, to the use of corporate facilities and resources.

In parts of Asia, housing – often job-related – is given to employees or a housing allowance is provided. This is especially so in the public sector, and it is also seen in South Asian banks and certainly throughout Asia for expatriates in managerial positions. In contrast, pensions, insurance and child care facilities are less common than they are in the West.

3.4.3 Rewards packages

As can be seen from the above, an organisation has several options when putting together the components of a total rewards package. Some key points should be made on this aspect of rewards:

1. There is a trend towards diversity in packages in the West, but in some parts of Asia reward generally means cash – and paid now. The package rarely includes stock options and ‘transparent’ profit shares.

2. The proportion of the total cost of rewards packages accounted for by benefits varies between (and within) countries, sectors and organisations. In parts of Asia benefits generally make up a higher proportion of the rewards package, despite employees’ preference for cash or near cash, than is the case in Europe or the US.

3. There has been increasing complexity in the types of benefit, especially for senior management.

4. The trend has been for the proportion of benefits within packages to rise sharply, especially when housing and pension/provident fund contributions become a large part of the benefits package. In parts of Asia great value is placed on conspicuous symbols of success, so management staff will certainly wish to have a prestige car, club membership and an expense account to impress others. Furthermore, despite what has been noted about Asians valuing immediate cash, senior management will prefer these expensive obvious ‘symbols’ as well as less obvious cash.

We can see these ideas and issues in action. One Asian example, Vietnam, is described in Text Box 3.1.

3.4.3.1 Issues and problems

These developments in the area of rewards can create problems for management and the business. Employees generally do not value the ‘worth’ of the benefits components of a package as highly as their ‘real’ cost. This may be for a variety of reasons. It may be because the services are not needed or might be inappropriate: for example, benefits could include child and maternity leave for employees with no children, or insurance for someone whose religious faith forbids the use of insurance – these benefits are of no worth to such employees. Then there is the ‘life cycle’ question, when different types of benefit have varying levels of attractiveness over the career and increasing age of the person for whom they are provided. This can be observed in terms of the relative importance over a person’s working life of benefits such as vacations, pensions and health care, where younger people prefer holidays and older workers prefer health care and savings.

A more generic problem has emerged in many economies with major traditional benefits, pensions and provident funds, which are more usual than pensions in parts of Asia. Developments such as the escalating costs of final salary pensions, the expense of provident fund contributions and the high volumes of early retirements in some public sector occupations have forced businesses to limit and withdraw final salary pensions and try to reduce provident fund contributions and for governments to struggle to meet the commitments made to public sector workers. This potential pension and provident fund commitment causes some Asian employers to keep basic pay low but use cost of living allowances (COLA), bonuses and benefits (which are usually not included in the calculation of pension and provident elements) to make up the rewards package.

3.4.3.2 Responses

One response to the management problem of this ‘cost-appreciation’ equation in benefits has been to move towards flexible benefits plans, or ‘cafeteria benefits’. This system allows employees some choice of benefits and the ability to have a varying ‘pick and mix’ total rewards package. This process is aimed both at reducing overall costs and increasing the recipient’s awareness of the ‘real’ costs of benefits. This is an attempt to link benefits more closely to motivation and performance.

Thus, HR are provided with a total benefits budget and a costed benefits ‘menu’. From this list is created an individual total benefits package – for example, taking a larger chunk of the package in up-front benefits (such as pay) vis-à-vis deferred benefits (such as pension) or more of one type (such as childcare) over another (such as a car). This construction of individual, customised benefit packages can be undertaken on a regular basis. However, as with much in HRM, this increasing complexity may come with additional costs to the organisation, not least in terms of the time involved. One possible way to mitigate some of the problems here is to outsource rewards calculation and provision to bespoke providers in this field. Partly as a consequence, flexible benefits have been implemented less in some parts of Asia where ‘take it or leave it’ is the usual choice. Nevertheless, there are some Asian examples, such as the flexible benefits system in the South Korean public sector (Yu, Walder and Rowley, 2008).

3.4.4 Levels

Reward systems and packages can differ at both various levels and locations within the same organisation. These range from the more collective, such as occupation or industry level, company or enterprise, plant, business unit, section or department level, down to the more individual packages. These rewards can be negotiated in different ways, such as with collective bargaining, and agreements can be made covering longer or shorter periods.

3.5 Determinants

We now move on the complex and emotive area of what actually determines the size of a total rewards package.

A constant problem area that produces much angst and publicity is the amount of remuneration given, especially at either end of the high-to-low rewards spectrum. The media reports both ‘scrooge payers’ and ‘fat cats’, a situation that is even more difficult to handle for the organisation if it is seen simultaneously as both a ‘scrooge’ to most staff with ‘fat cats’ in high places; it is also inconsistent in terms of the criteria used to justify reward levels.

A classic instance of the double standard argument involves assertions that, on the one hand, there is the need to ‘pay for the best’ while, on the other hand, there is the need to ‘pay what the market indicates’. Furthermore, there is no real market for senior managers; the vast majority remain home country nationals – for instance, only one in five of US corporations operating outside the US actually has a non-US national on the board. There has been more recent backlash against very high reward levels, even in the bastion of such practices, the US: Jack Welch, the feted ex-boss of GEC, was forced to renounce some of his retirement package (including the use of private jets) from mid-2002.

What are such reward levels based on? Is anyone worth the hundreds of millions of dollars paid to some US senior executives? It is worth taking a moment here to jot down the justifications you would use for why you are paid what you are. Can you group these reasons into criteria?

We can see some of the disparate issues in this area of rewards in the Asian example in Text Box 3.2.

Levels of reward often depend on external and internal factors as well as the relative strength of the individual employee and market forces. These include a range of factors, which can be grouped into the following.

3.5.1 HR individual characteristics

First, there are the individual characteristics of the person concerned. These include elements such as age and experience, as well as qualifications, skills and performance. While age considerations are not allowed to be a factor in much of the West, in parts of Asia age and length of service are major influences in setting pay – the young have low pay and the older (while still able to work) receive higher pay. This raises a fundamental question: are rewards given for ‘contributions’, ‘services rendered’ or ‘value-added’ by the person concerned? There is then the aspect of a person’s ‘potential’ to be considered. These are commonly the first factors to be used to justify levels of reward.

3.5.2 LM characteristics

Second, there are a range of LM factors that can come into play at different times and with various degrees of relevance. These include not only labour supply and demand, but also interventions in the LM, such as competitive pressures, the ‘cost of living’, and so on. An example of competitive pressures in the LM can be seen in relation to key IT specialists leading up to the expected ‘Millennium Bug’ in the late 1990s. The higher reward levels within China (as between Shanghai compared to Xian) is an example of the cost of living argument.

Yet, as we know, LMs are not ‘perfect’. They can be ‘sticky’ and operate ‘imperfectly’ (see Chapter 1, 1.7.2.1). Furthermore, there can be interventions which distort ‘pure’ LMs. These include (a) trade unions, with their collective bargaining forcing reward rates higher than would exist otherwise, and (b) the state by, for example, using pay policies, introducing minimum wages and equal pay, or encouraging certain types of reward system (such as profit sharing).

3.5.3 Job characteristics

A major set of reasons often used to justify reward levels concerns the type of job itself. These include the responsibility and skill requirements of the particular position and also relativities (differences in levels of pay between different types of job) compared to other jobs. These relativities are based on comparisons. These comparisons can be made with other people, in the same or different jobs, inside and outside the organisation and specific LM, and also socially (such as with family, friends, relatives or historical comparator groups) and relativities of these jobs with other jobs in the past.

This argument about relativities is linked to what is called the ‘going market rate’. The going market rate sets the ‘floor’ level of rewards for a job. People will begin to leave the organisation if the current rate received is felt to be too far out of line with the market rate. Relativities, like absolute levels of pay, result partly from competitive forces in LMs, interventions on the part of trade unions and governments and administrative decisions within organisations, such as the use of job evaluation.

3.5.4 Job evaluation

An important technique used to justify the level of reward is to base it on job evaluation. One of the fundamentals of a good rewards system is that employees believe it to be ‘fair’ and, above all, it is ‘seen to be fair’. Rewards should recognise that some jobs are more demanding or difficult than others and the more demanding or difficult the job the better it is rewarded relative to other jobs in the organisation. Yet, fairness can still be sought. How can fairness be attained and differences justified? The classic way is to calculate rewards via job evaluation.

Job evaluation is the process of determining the ‘worth’ of a job to an organisation. This process internally compares the relative ‘value’ of jobs. It is used to compare jobs, not to assess a single job in isolation from others. The purpose is to assess the relative difficulty or responsibility of a number of jobs so as to put them into ranked categories, which might then be used as the basis of a rewards system which is seen to be fair and orderly. Therefore, another way to justify rewards is to say that the level has been set for the job itself and that this has been done ‘objectively’ as the result of job evaluation. Job evaluation has other important roles, such as its use in ‘fairness’ (or at least being seen to be fair) and as a defence by businesses in discrimination claims where it is claimed that those doing work of a similar nature are paid at different rates.

The following (both non-analytical and analytical) methods of job evaluation are some of those more commonly used. They are, as in much of HRM, better seen as systematic, rather than scientific, processes and they range from the simpler and less costly in time and money to the increasingly complex and expensive. As ever, there is a trade-off between cost and sophistication.

3.5.4.1 Ranking

Ranking is the least systematic method of job evaluation and is the one often used in parts of Asia. Here jobs are simply ranked in order on the basis of given criteria. These criteria may include market value, responsibility, difficulty, criticality to organisational success, skill required, and so on. The ranked jobs are then divided into grades and a rate of pay fixed for each grade is attached.

However, because this system is subjective and arbitrary, it can create dissatisfaction amongst those employees who feel that the system is unfair or is manipulated by the bosses. Also, the extent of differences in criteria, such as difficulty and responsibility, are not readily established with this method.

3.5.4.2 Grading (job classification)

This approach to job evaluation is similar to ranking except that classes or grades are established first, and jobs are then placed into these pre-formed grades. Jobs are usually evaluated on the basis of the whole job using one factor, such as difficulty. Although grading is more systematic than ranking, there does remain a largely subjective dimension and, therefore, it can cause disgruntlement among employees. Yet, this is a common means of evaluating jobs in parts of Asia and is usually established using very subjective criteria.

Some of the developments in the area of rewards have an impact here. One such development that has attracted much attention in the West and among international firms in Asia is ‘broadbanding’. This is an attempt to retain the positive features of traditional pay scales while reducing its less desirable aspects, such as tendencies to focus on promotion over performance, an unwillingness to undertake duties associated with higher grades and the inability to offer higher salaries to new employees. Basically, broadbanding involves retaining some form of grading system, but with a reduced number of grades or salary bands and with pay variations within them based on performance rather than the nature of the job. However, there is a desire to retain a skeletal grading system as this gives order to the structure and helps to justify differentials.

3.5.4.3 Points rating

More systematic methods of job evaluation include points rating systems, where each job is evaluated according to a standard set of criteria. Such systems can be obtained ‘ready made’, with consultants able to provide generic, off-the-shelf systems. There are many examples of factors and factor plan weightings. The International Labour Organisation has produced a list of factors used most frequently. Criteria can include requirements in terms of education, skills, experience, planning and co-ordinating, initiative, judgement and decision making. Each of these different criteria might earn a number of points within an established range depending on the level required by the job. The points earned under each heading are then added together to give a total for the job. The total determines the grade into which the job is placed.

Points rating is the most commonly applied job evaluation method in the West and is used by many international organisations in Asia as it is seen to be more objective and fair. Therefore, it is commonly used to assess comparable worth issues in disputes on equal pay because it allows for comparisons across job categories and types of employment.

There are various problems with job evaluation to consider and remember. Some of the more general can be seen in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3

| Issue | Characteristic |

| Time | Increasingly costly to raise ‘objectivity’ |

| Level | Too high or too low |

| Factor | Which chosen and weights critical |

First, this method may lead to reward systems where pay is determined by administrative, rather than LM, considerations. One consequence is a danger that rates for some types of HR may be either inadequate for recruitment, retention and motivation, or rates are unnecessarily high.

Second, the specific factors chosen and how they are exactly weighted is fundamental and critical, not least as it can produce the outcome desired. For instance, factors may well be biased and even discriminatory, which in the worst case scenario are self-serving, producing the result that organisations want to be achieved, often justifying why some jobs (often done by men) are paid more than others (often done by women).

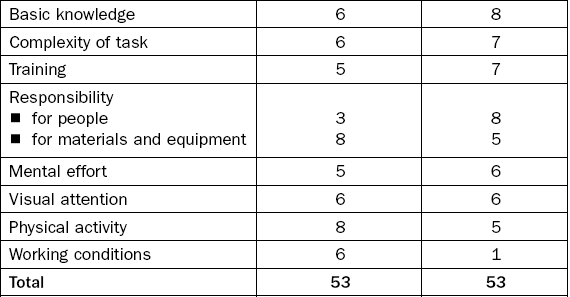

This can be clearly seen in the case in Table 3.4. The first example, using Factors (A), seems to ‘justify’ why maintenance fitters should be paid more than company nurses. After all, ‘objective’ job evaluation has been used in this endeavour, has it not? Given the gender segregation of work, it is obvious what the implications of this are. However, the second example using the same two jobs, but using different Factors (B), now indicates that they should be paid the same!

Table 3.4

Job evaluation using different job factors (each scored 1–10)

Source: Adapted from EOC (1985)

As we have just seen, the area of employee rewards, rather than being easy and simple as initially presented, is actually complex and often a minefield, with not just legal, but motivational and even PR aspects to it. Once we start to delve below the surface of employee rewards, there is little that is robust, objective or consistent. To make these matters worse are some of the recent trends in this area. One approach taken in an attempt to resolve for management some of the issues raised above is to try to link rewards to performance. After all, surely no one will object to those who work harder being rewarded for their endeavours and getting paid more than those who work less hard, will they? This brings us to the second main aspect of rewards – the area of performance-related rewards.

3.6 Performance-related rewards

There are two bases for these rewards. They are as follows.

3.6.1 Time-based systems

The basic wage or salary paid is negotiated on the basis of the actual time spent in attendance on the job or at the place of work. Even today, payment for many jobs is made in this simple way. Additional payments can be made above the standard rate for working, for example, overtime, shifts, weekends, unsociable hours, and so on.

Within these systems is the incremental pay scale. People are paid for the time they spend at work regardless of the effort they put in and, in this case, they are also paid an additional amount or increment each year that they work for the employer usually within the job grade. This is supposed to encourage employees to stay with the same organisation for a long period of time, rewarding long service and so result in a stable workforce. There is also an implication that people will become more knowledgeable and effective in their job while they work for more years to gain experience. Another advantage is that it is simple and easy to calculate pay. A version of this was the prevalent form of reward system for full-time male workers in large firms in some Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea, where it is known as ‘seniorityism’. This had cultural underpinnings, not least that esteem and wisdom are seen to come with age. However, the system was also aimed at reducing labour mobility so that the employers had a return on an investment in training and development (see Chapter 4 for more on this).

An important characteristic of time-based systems is that there is little about them to motivate employees to actually perform better. Also, employees can sometimes control and manipulate these payment systems to suit their own interests. It can encourage not only ‘clock watching’, but also an overtime culture, as this reward is paid at a premium to normal wages. At the end of their service employees are on their highest level of pay, but their most productive time was probably much earlier in their career.

In countries where an end-of-service payment is made (often a month’s pay per year of service), employers use this form of employee-enforced savings as working capital and at the end of the usual 30 or 40 years of employment some employers fail to pay out the amount owed. This has led to a strong preference for ‘cash now’ as opposed to deferred reward, not only in parts of Asia but also in some Western countries where the anticipated pensions or provident fund entitlements have not always been honoured.

3.6.2 Performance-based systems

It is these management issues and problems that have created the fertile ground for the search for alternatives in rewards. The idea of incentives in rewards is not particularly new. Nevertheless, managers continue to seek a method and formula for linking rewards to performance so that effectively it can be put on a type of ‘automatic pilot’. This leads to disputes when employees do not agree the method or formulae used. For example, staff of an international investment bank based in Hong Kong greatly resented their performance being ‘standardised’ with those based in Paris where the working hours and productivity were considered to be much lower. The capacity for hard work over long hours is found in parts of Asia. However, ‘standardisation’ using such Asian norms would be resisted in the West.

Performance-related pay (PRP) is the more topical version of this idea, although with a significant difference, for instance: ‘Incentives are used to stimulate performance, while performance pay is to reward it …’ (Torrington and Hall, 1998: 618). Indeed, there has been some shift in payment systems towards providing rewards for some form of performance (or ‘variable pay’ or ‘pay at risk’). Such systems reward individuals, groups or organisational units on their performance contributions. Performance-related rewards is an all-embracing term which includes rewards that recognise personal contributions and provide employees with opportunities to participate in the financial success of the organisation.

3.7 PRP schemes

PRP has several aims, which – along with the obvious objectives of improving motivation and performance as well as recognising differential contributions – include trying to attain strategic goals and reinforce organisational norms. PRP is based on some form of appraisal of the job holder against inputs (traits, skills) and/or outputs (objectives). This can take a number of forms. The schemes can be related not just to individual, but also to team, group and plant-wide performance. However, businesses need to ensure that participation in team rewards does not conflict with rewards offered by individual schemes. If there is tension or conflict, individuals, especially in the West, may decide it is more profitable for them to work alone rather than participate in joint team efforts. In parts of Asia there will be great pressure to have group rewards rather than rewards based on individual contribution. This is mainly because the community spirit is greater in some parts of Asia than it is in the West where the individual is considered to be more important than the group. In parts of Asia loyalty and personal needs are thought to be more important than individual contribution or capability. However, among the younger generation of workers, particularly among the elites in India and China, ‘greed’ rather than ‘need’ seems to be the prime motivator; in this respect, therefore, there does seem to be some convergence between Western and Asian expectations of PRP.

A variety of PRP schemes exist. They include the following.

3.7.1 Payment by results

Historically, the most widely used incentive scheme has rewarded employees according to ‘results’, such as the number of units of work produced or reduced time taken to produce the units – the more you produce, the more you are paid. One example of this reward system is piecework, which is the standard form of payment in factories in China, India, Pakistan and other Asian countries. Alternatively, the incentive can be paid for time saved on the ‘standard time’ in performing a specified operation, as derived from work study (which we covered in Chapter 2).

Yet, there is a need to cater for problems such as external influences depressing output by, for example, machine failure, raw material delays and demand fluctuations. A solution to these issues was measured daywork. In this reward system, instead of variable rewards corresponding to output achieved, employees are paid a fixed sum so long as they maintain a predetermined and agreed level of working.

Again, some of the drawbacks of this form of system are apparent, such as speeding up to achieve the given output in a shorter time span – an example being a large-scale bakery where the speed of part of the line (i.e. the conveyor belt through the ovens) is increased to achieve the output, but now over a shorter time period. There may well then be quality problems arising from such changes.

3.7.2 Skills-based

This reward system seeks to reward employees for the skills, or competencies, which they acquire. Its most obvious benefits are to encourage multi-skilling and functional flexibility, while simultaneously indicating the organisation’s commitment to HR development (see also Chapter 4). Most reward systems of this nature reward people with additional increments to their base pay once they have completed defined skill modules. Obviously, such a system needs close monitoring and managing to ensure that the skills learned and rewarded are actually the ones needed by the organisation. This form of reward system is more established in the West and is less common in parts of Asia, where (as will be seen in Chapter 4) some employers can sometimes be reluctant to increase the skill level of employees in certain sectors and levels.

3.7.3 Performance bonuses

These reward systems include temporary increases to base pay that are tied to specific performance outcomes. There are a plethora of methods, which include the widely used practices of paying a commission on sales and tipping for service. Another common method is for an organisation to set up competitions to achieve particular targets (for instance, an increase in sales) and to reward those who achieve those targets. This reward system may well have the effect of improving productivity, but unless all employees feel they have the opportunity to win, some may feel it is not worth the bother of making the extra effort. Rewards need to be managed efficiently or employees may well end up feeling cheated for the extra efforts made, with obvious effects on their future performance as well as on employee relations.

Another issue is that in some Asian societies individuals do not want to stand out ahead of their peers, so rewards based on competition within workgroups are not welcomed. In general, some Asians consider that harmony is more important than individual reward, so competition between workers is considered to be disruptive while competition between groups is accepted. A good example of group competition was seen when the Malaysian government chose Japanese and Korean construction firms each to build one of the Petronas Twin Towers that dominate the Kuala Lumpur skyline – the two firms competed on quality and speed to complete its own tower ahead of the other.

3.7.4 Instant or ‘spot’ bonuses

These reward systems recognise exceptional contributions. They may even take the form of senior managers walking around the workplace with an open cheque book to give instant rewards. These bonuses need to be set realistically and not awarded on an arbitrary basis, otherwise employees may feel that favourites are getting the rewards and others are neglected.

3.7.5 Profit sharing

There are a number of ways in which rewards can be linked to profit levels. Cash-based schemes represent the traditional and most common arrangement, whereby employees are paid a cash bonus, calculated as a proportion of annual profits. Such a system is found among some Asian employers who may give amounts such as one month’s (‘the 13th month’) pay as a bonus to all employees in a good year. Gainsharing is a variant, and this, importantly, can apply to non-profit making organisations. Here the bonus relates to costs saved rather than profit generated. This form of reward system is rare in Asia but is more common in the West.

3.7.6 Stock options

Rather than cash, shares can be awarded to employees. This group of rewards is provided in an increasingly complex manner in the US and UK, in particular. Some businesses may offer lower-level employees the opportunity to buy shares in their companies at preferential rates. This is seen as a way of encouraging employees to ‘think like owners’ and, therefore, to work harder to increase the value of ‘their’ business and ‘their’ shares in it. Few Asian companies use these systems, although it could be argued that the communist work organisations in China, Vietnam and North Korea hope for their workers to act like owners.

3.7.7 Employee involvement

The systems described above lead us to another area – the role and use of types of reward as forms of employee involvement (see also Chapter 5). In 1992 the European Union (EU) Council of Ministers adopted recommendations concerning the promotion of ‘Participation by Employed Persons in Profits and Enterprise Results’. Initiatives have already been taken in the UK and France to encourage profit sharing. Share ownership has been a continuing influence on these developments in the EU. Employee involvement, perhaps because of its socialist and communist links, is not encouraged in some parts of Asia, although Japanese organisations have welcomed and rewarded employee involvement in improving processes.

3.8 Difficulties with PRP

There can be enormous difficulties in introducing, running and managing PRP schemes.

The choice of scheme and its success are related to the extent to which a variety of factors are met. Some of these can be seen in Table 3.5 and below. Critically, it is often the case of ‘what gets measured gets done’.

Table 3.5

Factors to be considered in PRP

| Factor | Characteristics |

| Measure | Level at which performance can be objectively measured |

| Ability | Change actually results in better performance |

| Timing | Lag between performance and reward |

| Co-operation | Extent between individuals or departments |

| Commitment | Management committed and able to communicate goals |

| Involvement | In scheme design (e.g. targets set seen as important) |

| Trade unions | Agree/oppose (e.g. impacts on goals/collective bargaining) |

| Acceptance | Employees accept and understand plans |

| Corporate culture | Not in conflict with culture (e.g. UK public sector) |

| Employee culture | Sensitive to cultural values of employees (e.g. Asian) |

| Calculation | Easy and direct reward for effort made – ‘line of sight’ |

Important aspects of PRP include the freedom and ability to actually increase performance, clear attribution of the source of any increased performance and short time to the reward. A key requirement of any contingent reward scheme is that people should have a clear ‘line of sight’ (see Figure 3.1) between what they do and what they will get for doing it. This concept expresses the essence of expectancy theory: that motivation takes place only when people expect that they will receive worthwhile rewards for their effort and contribution.

![]()

Figure 3.1 The line of sight model Source: Adapted from Lawler (1990)

However, the time gap between increased performance and any reward may not actually operate as prescribed. For instance, the rewards through shares may be a long time coming, and the size of such rewards may also be small. In profit-related schemes both the ‘ability to influence’ and the time lag factors come into play. For example, any extra performance may not result in any improvement in share prices, which are affected by many factors other than just employee performance. Not only may the individual have very little influence on shares or profits, but the time gap between any enhanced performance and reward received for it may be very long and tenuous. Furthermore, the actual amounts paid out under such schemes may be fairly negligible. All these have obvious implications for motivating HR.

The problems of rewarding people using PRP and incentives across occupations and sectors, and links to motivation, are apparent. Assessing performance objectively remains difficult. It remains a perennially difficult task for management in a whole range of areas of HRM, including performance appraisals, training and development (see Chapter 4). One possible way forward is to develop a more sophisticated and nuanced range of criteria. Such an approach is the Balanced Scorecard method (Kaplan and Norton, 1996) whereby measurements are put in place to answer the four questions set out in Table 3.6.

Table 3.6

Questions and perspectives using the Balanced Score Card in rewards

| Question | Perspective |

| How should we appear to our shareholders? | Financial |

| How should we appear to our customers? | Customer |

| In which business processes must we excel? | Internal |

| How will we sustain our ability to change/improve? | Learning and growth perspective |

Source: Based on Kaplan and Norton (1996)

In sum, there are advantages and disadvantages to both of the main categories of reward system, neither of which is a complete solution to management and organisational problems. These are compared and contrasted in Table 3.7. This again indicates the contingent nature of employee rewards, as is often the case in HRM.

3.9 Rewards in practice

Employee rewards can be seen in practice in a variety of areas. Set out below are some examples in the form of strategically related rewards and top management pay; also considered are variations in employee rewards in terms of PRP within organisations, attempts to spread PRP to non-private sector organisations, and international variations and examples.

3.9.1 Strategic employee rewards

Rewards can be used strategically. One example can be seen in Case Study 3.2 concerning Richer Sounds, the UK hi-fi music equipment retailer, as explained by Marchington and Wilkinson (2002). An Asian example is Smartphone of Hong Kong, where high quality customer service is a crucial part of the company’s business plan and staff are expected to treat all customers well.

Rewards can also form part of a wider performance management system in Asia; this can be seen in South Korea (see Yang and Rowley, 2008) or China (Poon, Wei and Rowley, 2009).

3.9.2 Top management pay

A fundamental aspect of any reward system is that employees feel that the pay system is fair, reasonable and equitable. There is a widespread and increasingly vocal debate about top management pay, which often grows much faster than general pay increases. This has led to hostile public opinion and press coverage (using the derogatory term ‘fat cats’). The issues revolve around how top management remuneration is set, how it is linked to ‘performance’ and how it rewards ‘success’ (or not). This debate involves not only the total amounts, but also the disparities with the rest of the organisation’s workforce.

In 2007, for example, the earnings of US executives included the following:

![]() William McGuire (United Health) – US$1.1 billion

William McGuire (United Health) – US$1.1 billion

![]() Hank McKinnell (Pfizer) – US$213 million

Hank McKinnell (Pfizer) – US$213 million

![]() Bob Nardelli (Home Depot) – US$210 million

Bob Nardelli (Home Depot) – US$210 million

In 1997 in the US the average total direct remuneration of CEOs was 326 times that of the average employee (compared to 19 times in the UK). US average annual compensation (in real terms) of CEOs as a multiple of average worker pay was, in 1970, 39 times at US$1.3 million, but by 1999 it was 1,000 times higher at US$37.5 million. The fall-out of the post-2008 global financial crisis has also brought many other examples into the open, including the £700,000 annual pension for life from the age of 50 for the ex-head of one failed bank.

In some Asian countries, such as Japan, the multiple of CEO to average worker’s pay is far lower than in the West. There are some examples – for instance, Pakistan – where the multiple is much closer to that of the US. If non-cash benefits, such as golf club membership, are included, then in parts of Asia multiples are higher between the highest and the lowest paid in an organisation. Hong Kong and China already have differentials in excess of 500 between the pay of CEOs and average workers. This is not just because average workers have low pay but because Chinese CEOs (especially in banking and investment) receive rates of pay similar to those of international top managers.

During 2007 the Singapore government increased salaries for ministers and top civil servants to become among the highest in the world. The President of Singapore is now paid almost S$4,000,000 (US$290,000) a year, which is getting close to the US$400,000 paid to the President of the US – who governs a much larger country. The rationale of the Singapore government is that, to attract and retain the best talent, high rewards are justified. One may wonder what is the rationale of Western countries such as the US and UK, which pay politicians and civil servants much less than industrialists and bankers. Part of this may be to reflect on the notion of intrinsic rewards as well as deferred rewards, such as pension, security, lucrative later jobs and the patronage/honours system.

3.9.3 Use of PRP by HR level

There is also varied use of PRP schemes by organisational hierarchies, which can be seen in Table 3.8.

3.9.4 Use of PRP by organisations

Contemporary examples, in the West and in some international organisations in Asia, involve attempts to introduce more performance-related elements into the pay of both the private sector, such as retail banking, and the public sector, with groups such as health workers, teachers and the police force.

While, at first sight, these PRP initiatives may seem eminently desirable, it does not take long to see some of the problems and management issues that may arise. Even if we take the use in retail banking, how is performance measured? Is it based on ‘sales’? If so, of what and by whom? Not only may distortions and product mis-selling occur, but ‘churn’ (i.e. where customers use products for only a short period of time) may arise. Some employees may have no opportunity to achieve sales given the nature of their job. In the public sector, the same issues arise in an environment determined by the ethos of a ‘service’ and professionalism rather than pay for performance.

3.9.5 International variations in rewards

There are many differences internationally between rewards (also see White and Drucker, 2000: Chapter 9). Reward systems remain varied between countries. We will give a few examples of these variations. In Japan the ‘nenko’ system of seniority pay gives greater emphasis to an employee’s seniority within the organisation. Similarly, in South Korea a system of ‘seniorityism’ was prevalent. In China there was the ‘one big pot’ reward system, especially in the large state-owned enterprises (SOEs). While these SOEs have declined, shedding 25 million workers between 1998 and 2001, there are still 50,000 SOEs employing 50 million people using variations of the ‘big pot’ system. The changing patterns of rewards in Asia can be seen in Wei and Rowley (2009). The use of rewards in MNCs in Asia (US and Japanese in Vietnam) can be seen in Vo (2007). Some examples of Asian reward systems can be seen in Text Boxes 3.3 and 3.4.

India presents a further example. The Indian Railways system of rewards is based on long-developed public sector comparator groups with slow progress up the salary grades. The Indian government has appointed a Sixth Central Pay Commission to consider reward systems for its 1.6 million staff.

It is expected that the Central Pay Commission, will recommend substantial increases in pay and a reduction from the current 50 + grades (previously there had been over 500 grades), will reduce the difference between the maximum and minimum of the various grades and allow faster movement up the grades. The staff of Indian Railways seek comparison with the private sector – especially banks, customer contact centres and IT firms (where staff have benefitted from internationalisation of pay scales) rather than state and central government comparator groups.

In the US it is common to give very high rewards and bonuses to individual managers. Pay differentials between employees and managers used to be much greater in the US and UK than in many Asian countries, but some sectors in India and China now have levels of differentials more similar to those in the US and UK. Equal pay is of much greater concern in the West than it is in Japan, South Korea and China where women employees have traditionally had a separate status which is lower than that of male employees (Rowley and Yukongdi, 2009). Collectively bargained rewards remain more important in some countries, such as South Korea and Japan, than in others, such as Indonesia and Thailand, and also for some sectors, such as manufacturing, than for others, such as the hospitality industry.

Employee rewards are affected, therefore, not only by individual performance, but also by national criteria. Such criteria can be cultural, such as a society’s expectations (for example, for high pay amongst US managers) or more egalitarian. Government strategies, as in Singapore, can sometimes deliberately make labour costs comparatively high to force employers to move up the added value chain. We will return to these themes in Chapter 6.

On the subject of international rewards, the following guide to international compensation systems has been developed by Milkovitch and Newman (1996). The first part contains the following four segments.

1. Economic: completive dynamics/markets; capital flow/ownership; taxes

2. Employee: demographics; knowledge/skills; attitudes/preferences

3. Organisational: strategic intent; technology innovation and work roles; autonomy and information flows

4. Institutional: culture/politics; social contract; trade unions and employer federations

The second part is to examine strategic similarities and differences between countries by six criteria:

3.10 Conclusion

The subject of employee rewards continues to be as important and emotive an issue especially in some of the rapidly changing Asian countries such as India and China, where high pay for managers and owners has increased while millions of workers exist in poverty. There are attempts to ‘justify’ pay levels by reference to a range of factors, which includes an attempt to be more ‘objective’ by using more ‘rigorous’ forms of calculation, such as job evaluation, not least as a defence against claims of bias and discrimination in those countries that have passed legislation forbidding forms of discrimination.

There are two basic types of rewards system: those in which the key variable is either (a) time or (b) output. They are not mutually exclusive; hybrids are quite common. Changes occur and fashions come and go over time in the area of remuneration. Different rewards systems may be used for different grades of staff, especially between management and shop floor workers. However, there have been general moves towards paying for performance.

Reward systems vary significantly between and across sectors and countries. In recent years, in the West, major issues around pay have been associated with PRP and equal pay. With the growth of international corporations, structuring an equitable reward system for employees from different countries is a major concern.

References

Armstrong, M. Employee Rewards. London: CIPD; 1999.

The Economist. Japan’s wage round: Heading down, 2003. [8 March, 72.].

EOC, Job Evaluation Free of Sex Bias, 1985.

Galunic, C., Weeks, J. Investments that build on human nature. Mastering People Management, Financial Times. 2001; 5. [12 November, 10–11.].

GTZ, Salary systems in Vietnam, 2006. Available at. http://www2.gtz.de/vietnam/download/salary_system_in_vns_public_administration_en.pdf [(accessed 17 December 2007).].

Guerra, F., Chung, J., Fear of falling executive pay. Financial Times. 2008. [6 January, 11.].

Hainsworth, G.G. Human resource development in Vietnam. In: Than M., Tan J.L.H., eds. Vietnam’s Dilemmas and Options: The Challenges of Economic Transition in the 1990s. Singapore: Institute of South Eastern Asian Studies; 1993:157–206.

Harry, W.E. Employment creation and localisation – the crucial human resources issues for the GCC. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2007; 18(1):132–146.

Hille, K. Incentives shift for Taiwan’s tech workers. Financial Times. 2008. [25 September].

Kaplan, R.S., Norton, D.P. The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 1996.

Koh, Chin Seng. Case 7 – Change in bonus payment system. In: Alas R., ed. Implementation of Changes in Chinese Organisations. Oxford: Chandos, 2009.

Kuruvilla, S., Venkataratnam, C.S. Economic development and industrial relations: The case of South and Southeast Asia. Industrial Relations Review. 1996; 27(1):9–23.

Lawler, E. Strategic Pay: Aligning Organizational Strategies and Pay Systems. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1990.

Marchington, M., Wilkinson, A. People Management and Development: HRM at Work. London: CIPD; 2002.

Milkovitch, G., Newman, J. Compensation. Chicago: Irwin; 1996.

Nigh, V. ‘Lubricating the system’, 16 May–7 April at Missouri Department of Agriculture, weblog post, Doing business in Vietnam Seminar, Ag Business Development Division, 7 April. Available at http://dbivietnam.blogspot.com/2008/04/lubricatingsystem.html, 2008. [(accessed 10 September 2008)].

Poon, I., Wie, Q., Rowley, C. The changing face of performance management in China. In: Rowley C., Cooke F., eds. The Changing Face of Management in China. London: Routledge, 2009.

Rowley, C., Yukongdi, V. The Changing Face of Women Managers in Asia. London: Routledge; 2009.

Shen, J. Labour Disputes and their Resolution in China. Oxford: Chandos; 2007.

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Report of the Survey on Corruption in Vietnam 2005. Hanoif: Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam; 2005.

Taylor, R. The truth about work. The Financial Times. 2001. [25 January].

Torrington, D., Hall, L. Human Resource Management. Harlow: Prentice Hall; 1998.

Vo, A. An investigation into the transfer of HRM policies and practices of US and Japanese companies based in Vietnam. In: Burgess J., Connell J., eds. Globalisation and Work in Asia. Oxford: Chandos, 2007.

Vo, A. The Transformation of HRM and IR in Vietnam. Oxford: Chandos; 2009.

Wei, Q., Rowley, C. Changing patterns of rewards in Asia. Asia Pacific Business Review. 15, 2009.

White, G., Druker, J. Reward Management: A Critical Text. Abingdon: Routledge; 2000.

Wilson, T., Rewards that work. Mastering People Management, Financial Times. 2001. [P.4, 5 November, 2–3.].

World Bank, Vietnam Development Report 2006, 2006.. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2005/12/02/000160016_20051202141324/Rendered/PDF/344740VN.pdf [Report No. 34474-VN. Available at, (accessed 3 April 2008).].

Yang, H., Rowley, C. Performance management systems in South Korea. In: Varma A., Budhwar P., DeNisi A., eds. Performance Management Systems: A Global Perspective. London: Routledge, 2008.

Yu, G., Walder, N., Rowley, C. The impact of flexible benefits and employee satisfaction. International Journal of Society Systems Science. 2008; 1(1):67–83.