Conclusion

6.1 Introduction

Over the course of this book we have looked at the terrain and the main contours of the key areas of HRM from the perspective of the common tensions inherent within it (see Chapter 1, Figure 1.1). These differences have implications for perspectives in HRM (see Table 6.1).

Table 6.1

Tensions in perspectives in HRM

| Tension | Perspective |

| Universal versus contingent | Implication for best practice |

| Short versus long | Time frames |

| Specialist versus line | Delivery |

| Espoused versus actual | Reality |

This includes the tension between the common desire to seek universal, simple answers to perennial HRM issues versus the contingent and complex reality of working life and the management of people.

There is then the implicit and inherent long-term timeframe of HRM versus the common short termism of many businesses (especially those in an Anglo-American context), some of which have been adopted by some organisations in parts of Asia. For instance, think of the ‘payback’ from sophisticated recruitment and selection, training and involvement.

Furthermore, there is the tension between HRM’s use by specialist practitioners or line managers. This has an impact on areas such as training and time as well as consistency and strategy.

There is a further tension in HRM – between espoused versus actual policies and practices. These tensions can be found both within and between organisations, such as those with a head office in the West and operations in Asia. Thus, the rhetoric of much management is about the value and importance of people as ‘our greatest asset’. Yet, this is combined with a continuance of working systems that do not seem to indicate support in practice of this platitude of valuing people. Again, this can be seen both in the West and in the context of some Asian employers who may constantly look for sources of ‘cheaper’ labour.

Therefore, with these considerations in mind, over the course of this book we have examined the key areas of HRM, along with their issues, theories and practices. This was undertaken in terms of the following broad areas.

![]() Employee resourcing – with particular attention to HRP, recruitment and selection

Employee resourcing – with particular attention to HRP, recruitment and selection

![]() Employee rewards – specifically, remuneration and performance- related pay

Employee rewards – specifically, remuneration and performance- related pay

![]() Employee development – principally, training and performance appraisal

Employee development – principally, training and performance appraisal

![]() Employee relations – with the employee relations system and employee involvement

Employee relations – with the employee relations system and employee involvement

6.2 Key points

This examination of HRM theory and practice has resulted in a set of key points and conclusions. These include the following.

6.2.1 How is HRM different?

The management of people has a long history, which we broadly traced. It can also be acknowledged that there are Asian views of effective people management systems dating back over millennia. HRM can be seen as either simply the latest twist in this, or a turn that has produced a radically different concept.

There are supporters of both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ camps here. There is the idea of ‘old wine in new bottles’ for some commentators. In contrast, for others, HRM is actually a distinctive approach ‘… which seeks to achieve competitive advantage through the strategic deployment of a highly committed and capable workforce, using an integrated array of cultural, structural and personnel techniques’ (Storey, 1995: 5). If we take some credence from the latter camp, how is HRM different? We can attempt to make distinctions in terms of the following three aspects of HRM.

Yet, what is the evidence and likelihood that HRM, conceptualised in this form, is actually in existence or developing? The answer to this, it seems, is ‘not a lot’. For instance, research shows that the take-up of HRM-type initiatives and a strategic quality is not always new or proved. This is for several reasons, which include the following.

6.2.1.1 Conflicts

There are conflicting tendencies and tensions within HRM, some of which may be mutually exclusive and so actually make the adoption of the ‘whole package’ of HRM somewhat difficult. This is so within some Asian organisations undergoing rapid change, which make the tensions even more challenging. To what extent, for instance, can management expect both high commitment and large investment in employee development consistent with high numerical flexibility from the same workforce?

6.2.1.2 Opportunities and constraints

There are HRM-type changes, policies and practices in people management. Yet, these can actually reflect pragmatic responses (as has commonly been the case in the areas of people management) to opportunities and constraints in the socio-economic and political environment (see Legge, 1995).

6.2.1.3 Reasons

The reasons for this failure to develop an HRM approach, as in some parts of Asia, is as a result of a set of factors related to the strategic role of people in organisations and the value that employers place on their effective management. However, it ‘… is not just a question of will or conviction, but of deep-seated features’ (Storey and Sisson, 1991: 174).

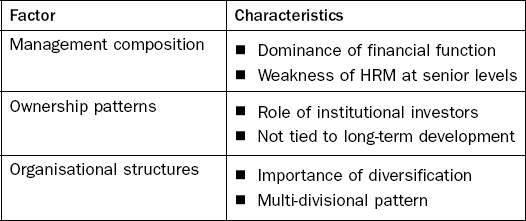

There are several possible reasons, including those noted in Table 6.2. These reasons constitute a group of impediments that are mutually reinforcing. Therefore, ‘[h]opes that HRM would lead to a more strategic approach to the management of human resources have been largely frustrated’ (Sisson, 1995: 105).

6.2.2 Dynamism

The emergence and development of HRM indicates the inherent dynamism and changeable nature of the area of work and employment and its management. We examined the management of people in Asia, as well as in the West, and considered some of the main practices, methods and implications and the issues and problems that may arise here. This examination indicated the need for a questioning approach as dynamic change continues to impact on organisations. A PEST (political, economic, social, technology factors) analysis shows important influences and impacts on this. Thus, management need to be aware of, and keep up with, changes that impact on HRM. Some of the main types of change in our broad HRM areas include the following.

6.2.3 Universal recipes or specific ingredients?

One reason why this dynamic change is important is that it affects ideas of ‘best practice’ in this field of management (Rowley and Poon, 2008). Yet, for one group of commentators the question remains – if we look hard enough, are there universal solutions to some of the key issues and practices in people management? This argument involves the commonality or peculiarity of HRM, the transferability or specificity of its practices to/from/within countries, including those in Asia. While these are not new issues, they have taken on powerful resonance in some rapidly changing Asian economies and societies. Part of this has been due to areas such as developments in the European Union and ideas of ‘common’ employment rights or a ‘level playing field’, and the exporting of such ideas as part of globalisation in business and management ideas. This area has been looked at in two ways.

6.2.3.1 Universalism

For this camp HRM is universal and this can be over time, industry sector and location. It is only a question of learning what these HRM techniques are (for example, the ‘best practices’), and then transfer them and apply them for maximum impact and benefit. Even if these techniques may have varied before, in an increasingly globalised and swiftly changing world they will vary less and less.

6.2.3.2 Contingency

In contrast to this first approach, some view management, especially HRM, as more specific and unique to its location and context. This is neatly indicated in the following quote: ‘Many aspects of management work can be developed into a science: successful personnel management is an art’ (Torrington and Hall, 1998: 696). What underpins this ‘art’ of people management? The factors include both culture (norms, values) and institutions (the state, organisation, trade unions), which retain salience and influence on the HRM system.

We can see the ideas and issues in these areas in the following two text boxes. Text Box 6.1 provides an analysis of ‘best practices’ in Asia in terms of definitions, application and types. Text Box 6.2 covers HRM transfers and business systems.

6.3 Comparisons

These points were discussed and highlighted when we looked at HRM comparatively and internationally. There are many differences in the use of HRM internationally between different countries as we have seen (and can be seen in, for example, Rowley, 1998; Rowley and Benson, 2000 and 2004; Rowley et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2007).

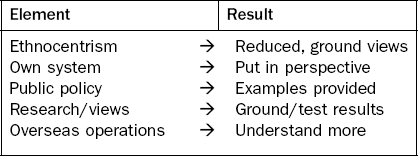

Comparative views are useful for a range of reasons. These include those noted in Table 6.3.

These differences may result from several factors. These can be explained by the reasons noted in Table 6.4.

Several options are available to look at HRM internationally. These can be seen in Table 6.5.

6.4 The future of HRM

Several organisational trends will have impacts on the development of HRM. These include the following.

6.4.1 HRM as a subject

HRM as a subject faces a healthy future in terms of academia, teaching and research – partly driven by the increasing popularity of business and management qualifications at different levels. Within these qualification courses, the study of people management is covered in a variety of ways and from various aspects. Much research in the area is durable and is continuing, although the exact focus of this continues to change and develop. Thus, there is less work on ‘conflict’ and more on the contributions by HRM to the performance of businesses and economies, for instance.

6.4.2 HRM as a function

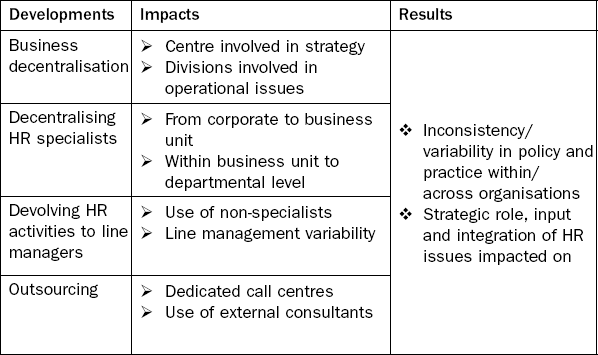

As a function, HRM faces a different set of issues. For some commentators, it may lead to a decline, although others see some greater continuity functionally. A range of developments will have different impacts on the HRM function.

The impacts are numerous and varied, as can be seen in Tables 6.6 and 6.7. While the management of people will remain, it seems that who does it, and where, may change. One of the more recent trends in countries such as the US and UK is to outsource either the whole of the HRM function or certain aspects of it, such as recruitment, to specialists. Yet, what is the likely impact of such outsourcing for ideas of HRM and consistent universal frameworks?

Table 6.7

| Decline | Continuity |

| In recession, fewer people resourced, rewarded, developed | In recession, still deal with redundancies, retaining even recruiting |

| Trade unions more docile, less ‘trouble-shooting’ | Trade unions remain, alternative sanctions (i.e. overtime bans, PR campaigns) |

| Routine administration reduced with automation (i.e. pay, records) | Increasingly heterogeneous workforce requiring managing diversity |

| Subcontracting out aspects (i.e. resourcing, rewards, development) | In economic boom, attract/retain sufficient quality key HR |

| ‘Macho management’ reasserting managers ‘right to manage’ | Myriad laws require consideration (i.e. need to consult over changes) |

6.5 Conclusion

The area of people management is not new and we have seen that directions for managing people have existed, even in Asia, for thousands of years. In the modern era, management of people has evolved and been labelled and relabelled in several ways. However, for some people HRM is different and marks a break with this past as HRM contains some elements that ‘old’ PM simply did not possess, or even claim that PM was interested in such topics. This sort of hard distinction is less proven in some parts of Asia where PM is currently stronger than HRM. Nevertheless, that should not distract businesses and managers from the fact that HRM remains critically important.

Furthermore, while HRM is important, the introduction and use of ‘text book’ practices varies between Asian organisations. We have examined this through a prism of context that has shown variability, and we have explored some of the many reasons (country, culture and sector) why this may be so. This variability in HRM needs to be remembered when faced with the often naïve nostrums and platitudes of many proponents of the latest ‘fashion’ to solve the HRM problems and issues of all organisations in Asia and elsewhere. If only managing people was simple, organisations would have solved their HR issues already! The management of people needs to be put in context and viewed through this lens.

References

Bae, J., Rowley, C. The impact of globalization on HRM: The case of South Korea. Journal of World Business. 2001; 36(4):402–428.

Bartlett, C.A., Ghoshal, S. Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution. Chatham, UK: Mackays; 1989.

Becker, B.E., Gerhart, B. The impact of HRM on organizational performance: Progress and prospects. Academy of Management Journal. 1996; 39(4):779–802.

Benson, J., Debroux, P. HRM in Japanese enterprises: Trends and challenges. Asia Pacific Business Review. 1997; 3(4):62–81.

Berggren, C. Introduction: Between globalisation and multi- domestic variation. In: Belanger J., Berggren C., Bjorkman T., Kohler C., eds. Being Local Worldwide: ABB and the Challenge of Global Management. New York: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Birkinshaw, J., Hood, N. ‘Multinational subsidiary evolution. Capability and charter change in foreign-owned subsidiary companies’, Academy of Management Review, 1998. 1998; 23(4):773–795.

Björkman, I., Xiucheng, F. HRM and the performance of Western firms in China. International Journal of HRM. 2002; 13(6):853–864.

Boxall, P., Purcell, J. Strategy and Human Resource Management. London: Palgrave; 2003.

Briscoe, D.R. International Human Resource Management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1995.

Cooke, F.L. Vocational and enterprise training in China: Policy, practice and prospect. Journal of the AP Economy. 2005; 10(1):26–55.

Dicken, P. Global Shift: Transforming the World Economy, 3rd edn. London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd; 1998.

DiMaggio, P.J., Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organization fields. In: Power W.W., DiMaggio P.J., eds. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press; 1991:41–63.

Dowling, P.J., Schuler, R.S., Welch, D.E. International Dimensions of HRM. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing; 1994.

Doz, Y.L., Prahalad, C.K. Patterns of strategic control within multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies. 1984; 15(2):55–72.

Drost, E.A., Frayne, A., Lowe, B., Geringer, J.M. Benchmarking training and development practices: A multi-country comparative analysis. Human Resource Management. 2002; 41(1):67–88.

Easterby-Smith, M., Malina, D., Lu, Y. How culture sensitive is HRM? A comparative analysis of practice in Chinese and UK companies. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 1995; 6(1):31–59.

Edwards, P., Ferner, A., Sisson, K. People and the Process of Management in the Multinational Company: A Review and Some Illustrations, Warwick Papers in Industrial Relations. Coventry: IRRU; 1993.

Edwards, T., Rees, C., Coller, X. Structure, politics and the diffusion of employment practices in multinationals. European Journal of Industrial Relations. 1999; 5(3):286–306.

Elger, T., Smith, C. Global Japanization? Convergence and competition in the organisation of the labour process. In: Elger T., Smith C., eds. Global Japanization? The Transformation of the Labour Process. London: Routledge, 1994.

Evans, P., Lank, E., Farquhar, A. Managing human resources in the international firm: Lessons from practice. In: Evans P., Doz Y., Laurent A., eds. Human Resource Management in International Firms. London: Macmillan, 1989.

Ferner, A. Multinational companies and human resource management: An overview of research issues. Human Resource Management Journal. 1994; 4(3):79–102.

Ferner, A. Country of origin effects and HRM in multinational companies. Human Resource Management Journal. 1997; 7(1):19–37.

Ferner, A. Occasional Paper No. 61.The Embeddedness of US Multinational Companies in the US Business System: Implications for HR/IR. Leicester: De Montfort University Business School, 2000.

Ferner, A., Quintanilla, J. Multinationals, national identity, and the management of HRM: “Anglo-Saxonisation” and its limits. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 1998; 9(4):710–731.

Ferner, A., Varul, M.Z. “Vanguard” subsidiaries and the diffusion of new practices: A case study of German multinationals. British Journal of Industrial Relations. 2000; 38(1):115–140.

Finegold, D., Soskice, D. The failure of training in Britain: Analysis and prescription. Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 1988; 4(1):21–53.

Gereffi, G. Commodity chains and regional divisions of labor in East Asia. Journal of Asian Business. 1996; 12:75–112.

Ghoshal, S., Bartlett, C. Creation, adoption, and diffusion of innovations by subsidiaries of multinational corporations. Fall: Journal of International Business Studies; 1988. [365–388].

González, S.M., Tacorate, D.V. A new approach to the best practices debate: Are best practices applied to all employees in the same way? International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2004; 15(1):56–75.

Guest, D., Hoque, K. National ownership and HR practices in UK greenfield sites. Human Resource Management Journal. 1996; 6(4):50–74.

Guillén, M. Is globalization civilizing, destructive or feeble? A critique of five key debates in the social science literature. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001; 27:235–260.

Hall, L., Torrington, D. The HR Function: The Dynamics of Change and Development. London: Financial Times/Pitman; 1998.

Hall, P., Soskice, D. An introduction to varieties of capitalism. In: Hall P., Soskice D., eds. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Hamilton, G. Overseas Chinese capitalism. In: Tu W., ed. The Confucian Dimensions of Industrial East Asia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1995:112–125.

Hirst, P., Thompson, G. Globalization in Question, 2nd edition. Malden, MA: Polity Press; 1999.

Hollingsworth, R.J., Boyer, R. Coordination of economic actors and social systems of production. In: Hollingsworth R.J., Boyer R., eds. Contemporary Capitalism: The Embeddedness of Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Huselid, M.A. The impact of HRM practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal. 1995; 38(3):635–670.

Huselid, Report published by the Japan Institute of Labour Policy and Training Retrieved 17 August 2007 from, 2004.. http://www.stat.go.jp/english/index.htm

Johansson, J., Yip, G. Exploiting globalisation potential: US and Japanese strategies. Strategic Management Journal. 1994; 15(4):579–601.

Kerr, C., Dunlop, J.T., Harbison, F.H., Meyers, C.A. Industrialism and Industrial Man. London: Heinemann; 1962.

Kopp, R. International human resource policies and practices in Japanese, European, and United States multinationals. Human Resource Management Journal. 1994; 33(4):581–599.

Kostova, T. Transnational transfer of strategic organizational practices: A contextual perspective. Academy of Management Review. 1999; 24(2):403–428.

Kostova, T., Zaheer, S. Organisational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management Review. 1999; 24(1):64–81.

Lado, A.A., Wilson, M.C. HR systems and sustained competitive advantage: A competency-based perspective. Academy of Management Review. 1994; 19(4):699–727.

Lane, C. Industry and Society in Europe. Stability and Change in Britain. Germany and France. Aldershot: Edward Elgar; 1995.

Legge, K. HRM: A critical analysis. In: Storey J., ed. New Perspectives on Human Resource Management. London: Routledge, 1989.

Legge, K. HRM: Rhetoric, reality and hidden agendas. In: Storey J., ed. HRM: A Critical Text. London: Routledge; 1995:33–59.

Marchington, M., Wilkinson, A. Human Resource Management at Work. London: CIPD; 2005.

Nohria, N., Ghoshal, S. The Differentiated Network. Organizing Multinational Corporations for Value Creation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1997.

Ohmae, K. The Borderless Word. London: HarperCollins; 1990.

Oliver, N., Wilkinson, B. The Japanization of British Industry: New Developments in the 1990s. London: Heinemann; 1992.

Orrù, M., Biggart, N.W., Hamilton, G.G. Organisational isomorphism in East Asian. In: Powell W.W., DiMaggio P.J., eds. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Pfeffer, J. Competitive Advantage through People. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1994.

Pfeffer, J. The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1998.

Porter, M. The Competitive Advantage of Nations. London/Basingstoke: MacMillan; 1990.

Pudelko, M. Cross-national learning from best practice and the convergence-divergence debate in HRM. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2005; 16(11):2045–2074.

Quintanilla, J., Ferner, A., Varul, M. Country-of-origin effects, host country effects and the management of HR in multinationals: German companies in Britain and Spain. Journal of World Business. 2001; 36(1):107–128.

Redman, T., Wilkinson, A. Contemporary Human Resource Management. London: FT/Prentice Hall; 2006.

Rosenzweig, P. The Halo Effect and the Eight Other Business Delusions that Deceive Managers. New York: Free Press; 2007.

Rowley, C. HRM in the Asia Pacific Region: Convergence Questioned. London: Frank Cass; 1998.

Rowley, C., Bae, J. HRM in South Korea after the Asian financial crisis. International Studies of Management and Organization. 2004; 34(1):52–82.

Rowley, C., Benson, J. Globalization and Labour in the Asia Pacific Region. London: Frank Cass; 2000.

Rowley, C., Benson, J. Convergence and divergence in Asian HRM. California Management Review. 2002; 44(2):90–109.

Rowley, C., Benson, J. The Management of HR in the Asia Pacific Region: Convergence Reconsidered. London: Frank Cass; 2004.

Rowley, C., Poon, F.H., HRM best practices and transfer to the Asia-Pacific region 21st Century Management.. C. Wankel. Sage, US: Los Angeles, 2008:209–220.

Rowley, C., Warner, M. Globalizing international HRM? International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2007; 18(5):703–716.

Rowley, C., Warner, M. Globalizing International HRM. London: Routledge; 2008.

Rowley, C., Benson, J., Warner, M. Towards an Asian model of HRM: A comparative analysis of China, Japan and Korea. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2004; 15(4/5):917–933.

Rowley, C., Zhu, Y., Warner, M. HRM with Asian characteristics. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2007; 18(5):745–768.

Schmitt, M., Sadowski, D. A rationalistic cost-minimization approach to the international transfer of HRM/IR practices: AngloSaxon multinationals in the Federal Republic of Germany. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2003; 14(3):409–430.

Sisson, K. HRM and the personnel function. In: Storey J., ed. HRM: A Critical Text. London: Routledge; 1995:87–109.

Smith, C., Meiksins, P. ‘System, society and dominance effects in cross-national organisational analysis’, Work. Employment and Society. 1995; 9(2):241–267.

Storey, J. Human Resource Management: A Critical Text. London: Routledge; 1995.

Storey, J., Sisson, K. Looking to the future. In: Storey J., ed. New Perspectives on HRM. London: Routledge; 1991:167–183.

Taylor, F. Scientific Management. New York: Harper and Row; 1911.

Taylor, S., Beechler, S., Napier, N. Toward an integrative model of strategic international human resource management. Academy of Management Review. 1996; 21(4):959–985.

Tempel, A. The Interaction of Country-of-Origin and Host Country Effects on Human Resource Management Practices in German and British Multinational Companies. Paper for Conference on Multinational Companies and Human Resource Management: Between Globalisation and National Business System Conference. De Montfort University, Leicester, 2001.

Thang, L.C., Rowley, C., Troung, Q., Warner, M. To what extent can management practices be transferred between countries? A comparative analysis of China, Japan and South Korea. Journal of World HRM. 2007; 42(1):113–127.

Tolbert, P., Zucker, L. The institutionalization of institutional theory. In: Clegg S., Hardy C., Nord W., eds. Handbook of Organization Studies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996:175–190.

Torrington, D., Hall, L. Human Resource Management. London: Prentice Hall; 1998.

Vo, A. An investigation into the transfer of HRM policies and practices of US and Japanese companies based in Vietnam. In: Burgess J., Connell J., eds. Globalisation and Work in Asia. Oxford: Chandos, 2007.

Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1964.

Warner, M. The Management of HR in Chinese Industry. London: Macmillan; 1995.

Warner, M. China’s HRM revisited: A step-wise path to convergence? Asia Pacific Business Review. 2003; 19(4):15–31.

Westney, D.E. Institutionalization theory and the multinational corporation. In: Ghoshal S., Westney D.E., eds. Organization Theory and the Multinational Corporation. Basingstoke: St. Martin Press, 1993.

Whitley, R. Societies, firms and markets: The social structuring of business systems. In: Whitley R., ed. European Business Systems: Firms and Markets in their National Contexts. London: Sage Publications, 1992.

Whitley, R. Presented to Sub theme 3. How and Why are International Firms Different? The Consequences of Cross-border Managerial Coordination for Firm Characteristics and Behaviour. Business Systems in their International Context, 1999. [of the 15th EGOS Colloquium held at the University of Warwick, 4–6 July 1999.].

Wilkinson, B., Gamble, J., Humphrey, J., Morris, J., Anthony, D. ‘The new international division of labour in Asian electronics: Work organisation and human resources in Japan and Malaysia’, Journal of Management Studies. July:. 2001; 38(5):675–695.

Yuen, E.C., Kee, H.T. Headquarters, host-culture and organizational influences on HRM policies and practices. Management International Review. 1993; 33(4):361–383.

Zhu, Y., Warner, M., Rowley, C. HRM with Asian characteristics: A hybrid people management system in East Asia. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2007; 18(5):745–768.