CHAPTER 10

Structured Notes

For a plain vanilla bond structure, the (1) coupon interest rate is either fixed over the life of the security or floating at a fixed spread to reference rate; and (2) the principal is a fixed amount that is due on a specified date. There are bonds that have slight variations that are common in the marketplace. A callable bond may have a redemption date that is prior to the scheduled maturity date. The option to call the bond prior to the maturity date resides with the issuer; the benefit of calling the issue depends on the market interest rate at which the callable bond issue can be refinanced. Similarly, a putable bond has a maturity date that can be shortened, but in this case the option resides with the bondholder; if the market rate on comparable bonds exceeds the coupon rate, the bondholder will exercise. A convertible bond typically has at least two embedded options. The first is the bondholder's right to convert the bond into common stock. The second is the issuer's right to call the bond. Some convertible bonds are also putable.

Callable, putable, and convertible bonds are considered traditional securities, as are other similar structures such as extendible and tractable bonds.1 There are bonds with embedded options that have much more complicated provisions for one or more of the following: interest rate payable, redemption amount, and timing of principal repayment. The interest or redemption amount can be tied to the performance or the level of one or more interest rates or noninterest rate benchmarks. As a result, the potential performance (return and risk) of such securities will be substantially different than those offered by plain vanilla bond structures. These securities are popularly referred to as structured notes.

Historically, the problem with structured notes has been that they have been purchased by some entities that are unfamiliar with their investment risks. As a result, their have been major losses for some financial institutions and some large corporations as well. For example, in 1994 a large number of banks experienced losses from investing in certain types of structured notes.

In this chapter, we discuss structured notes, including the investor motivation for investing in such notes, issuer motivation for creating them, the design of structured notes, and provide examples.

STRUCTURED NOTES DEFINED

In a 1994 report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the following description of structured notes appears:

Unlike straight derivatives whose entire value is dependent on some underlying security, index or rate, structured securities are hybrids, having components of straight debt instruments and derivatives intertwined. Rather than paying a straight fixed or floating coupon, these instruments' interest payments are tailored to a myriad of possible indices or rates. The Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB), one of the United States' largest issuers of such products, has more than 175 indices or index combinations against which cash flows are calculated. In addition to the interest payments, the securities' redemption value and final maturity can also be affected by the derivatives embedded in structured notes. Most structures contain embedded options, generally sold by the investor to the issuer. These options are primarily in the form of caps, floors, or call features. The identification, pricing and analysis of these options give structured notes their complexity.2

The key to structured notes is that derivatives are involved. In the previous definition, the authors state that “straight debt instruments and derivatives are intertwined.” Moreover, in this definition, the derivatives such as options are generally sold to the investor. What the definition suggests is that the issuer of a structured note may be exposed to the risk associated with having sold a derivative. For example, a structured note can have an interest rate that is tied to the performance of the S&P 500. The issuer of such a structured note is therefore exposed to the risk of a substantial interest expense if the S&P performs extremely well.

However, the above definition is not shared by all market participants. Consider the following two definitions. In a survey article of structured notes, Telpner defines structured notes as “fixed-income securities—sometimes referred to as hybrid securities that present the appearance of fixed-income securities—that combine derivative elements and do not necessarily reflect the risk of the issuer.”3 Here the key element is that the issuer is not necessarily taking on the opposite risk of the investors.

In their book on the structured notes market, Peng and Dattatreya write, “Structured notes are fixed income debentures linked to derivatives.”4 They go on to say:

A key feature of structured notes is that they are created by an underlying swap transaction. The issuer rarely retains any of the risks embedded in the structured note and is almost hedged out of the risks of the note by performing a swap transaction with a swap counterparty. This feature permits issuers to produce notes of almost any specification, as long as they are satisfied that the hedging swap will perform for the life of the structured note. To the investor, this swap transaction is totally transparent since the only credit risk to which the investor is exposed is that of the issuer.5

In this definition, the focus is not on the issuer selling a debt instrument with derivative-type payoffs to investors, but the issuer protecting itself against the risks associated with the potential payoffs it must make to investors by hedging those risks. That is, the upside potential available to investors in a structured note do not reflect the risk to the issuer. While Peng and Dattatreya say that this can be done with a swap transaction, any other derivative can be employed to hedge the risk faced by an issuer.

MOTIVATION FOR INVESTORS AND ISSUERS

The motivation for the purchase of structured notes by investors includes (1) the potential for enhancing yield; (2) acquiring a view on the bond market; (3) obtaining exposure to alternative asset classes; (4) acquiring exposure to a particular market but not a particular aspect of it;6 and (5) controlling risks.

The potential for yield enhancement was the motivation behind the popularity of structured notes in the sustained low-interest-rate environment in the late 1980s. After the high interest rates (double digits) that prevailed in the early 1980s, institutional investors faced interest rates that were not sufficient to satisfy the liabilities for the financial products they created during the high-interest-rate environment. Local governments had come to rely on interest income from higher interest rates in order to fund operations and avoid raising property and personal taxes. Structured notes offered the opportunity to provide a higher return than that prevailing in the market for plain vanilla debt obligations if certain market scenarios occurred.

The ability of issuers to hedge risk using derivatives allowed them to create securities for investors who had a view on the bond market. For example, a structured note could be created that allowed exposure to a change in the yield curve, the change in the spread between two reference interest rates, or the direction of interest rates (e.g., a leveraged payoff if interest rates declined).

Structured notes that have payoffs based on the performance of asset classes other than bonds allow investors to take views on other markets in which they may be prohibited from investing by regulatory or client constraint. For example, suppose that an investor who must restrict portfolio holdings to investment-grade bonds has a view on the equity market. The investor would not be permitted to invest in equities. However, by investing in an investment-grade bond whose payoff is based on the performance of the equity market, the investor has obtained exposure to the equity market. For this reason, some market participants refer to structured notes as “rule busters.”

Finally, a structured note can be used to hedge exposure that an investor may not be able to hedge more efficiently using derivative products. For example, suppose that an investor is concerned with exposure in its current portfolio to changes in credit spreads. While there are currently credit derivatives that would allow the investor to hedge this exposure, suppose that the investor is not permitted to utilize them. An investor can have an issuer create a structured note that has a payoff based on a particular credit spread. The issuer can protect itself by taking a position in the credit derivatives market.

But what is the benefit of all this customization for the issuer? By creating a customized product for an investor, the issuer seeks a lower funding cost than if it had issued a bond with a plain vanilla structure.

How do borrowers or their agents find investors who are willing to buy structured notes? In a typical plain vanilla bond offering, the sales force of the underwriting firm solicits interest in the issue from its customer base. That is, the sales forces will make an inquiry to investors about their needs and preferences. In the structured note market, the process is often quite different. Because of the small size of an offering and the flexibility to customize the offering in the swap market, investors can approach an issuer through its agent about designing a security for their needs. This process of customers inquiring of issuers or their agents to design a security is called a reverse inquiry. For example, the World Bank, a major issuer of structured notes, indicates that to propose a new issue, an investor can contact an underwriter or the World Bank directly. The criteria the World Bank will use in deciding to proceed with the transaction will be based on a minimum size of USD 10 million or equivalent in other currencies, a minimum maturity of one year, the complexity of the transaction, and the suitability of the proposed structured note for the issuer as well as the investor.

ISSUANCE FORM AND ISSUERS

A structured note can be issued in the public market or as a private placement or a 144A security. It can take the form of either commercial paper, a medium-term note, a certificate of deposit, or a corporate bond. A medium-term note (MTN) differs from a corporate bond in the manner in which it is distributed to investors when initially sold. Although some investment-grade corporate bond issues are sold on a best-efforts basis, typically they are underwritten by investment bankers. MTNs have been traditionally distributed on a best-efforts basis by either an investment banking firm or other broker/dealers acting as agents. Another difference between corporate bonds and MTNs is that when MTNs are offered, they are usually sold in relatively small amounts on a continuous or an intermittent basis as part of a continuous rolling program, while plain vanilla bonds are sold in large discrete offerings.7

The issuer must be of high credit quality so that credit risk is minimal in order to accomplish the objectives that motivated the creation of the structured note. Issuers include highly rated corporations, banks, and U.S. government agencies. Because credit risk increases over time, the type of issuer and the form of the security are tied to the investor's planned holding period of the investor. Exhibit 10.1 provides a summary of the relationships among the maturity profile of the investor, the typical form of the debt instrument, and the typical issuer.

CREATING STRUCTURED NOTES

Peng and Dattatreya describe the three main steps in creating a structured note:8

- conceptual stage;

EXHIBIT 10.1 Maturity Profile Factor, Typical Form of Instrument, and Typical Issuer

- identification process; and

- structuring or construction stage.

In customizing a structured note for a client, the investment banker must understand the client's motivation. This is the conceptual stage of the process. We described earlier why investors look to the structured note market for customization. The investor will provide the motivation through reverse inquiry.

In the identification process, the investment banker identifies the underlying components that will be packaged to create the structured note based on the requirements identified in the conceptual stage. This process begins with specifying five customization factors: nationality, rate profile, risk/return, maturity, and credit. The nationality factor specifies the country where the client would like to have some investment exposure. In the case of structured notes where the underlying is an interest rate, the rate factor determines the directional play (e.g., rising or falling interest rates, flattening or steepening yield curve) that is to be embedded in the structure. The amount of risk to be embedded in the structured note is the risk/return customization factor. Both the maturity and credit customization factors determine the instrument that will be used and the type of issuer as described in Exhibit 10.1.

In the structuring or construction stage, the investment banker gathers the pertinent market data and issuer-specific information. This information includes the target funding cost for the issuer (after underwriting fees) and the desired coupon and principal structure based on information from the conceptual and identification stages. In determining the cost of the structure, recognition must be given to the hedging cost that will be incurred when using the derivative instrument or instruments. Other specifications of the structured note that may have to be determined will depend on the complexity of the structure. For example, a structure may require that the correlation of the factors driving the price of the underlying instruments in the structure be estimated.

EXAMPLES OF STRUCTURED NOTES

A wide range of structured notes have been created in the market. Here we will discuss only two types: interest-rate structured notes and equity-linked structured notes.

Interest Rate Linked Structured Notes

The general coupon formula for a floating-rate security is

Reference interest rate + Quoted margin

A structured note whose coupon rate is linked to a reference interest rate has a coupon reset formula that differs from the one above. Examples include leveraged/deleveraged floaters, step-up notes, dual indexed, floaters, range notes, and inverse floaters. We discuss each below and in our discussion of inverse floaters, we describe how they are created with the use of interest rate swaps.

Leveraged/Deleveraged Floaters

A coupon reset formula could be as follows:

L × (Reference interest rate) + Quoted margin

where L is a positive value that is different from 1. Depending on the value of L, the structured note is either a leveraged or deleveraged floater.

When L exceeds 1 in the coupon reset formula, the structured note is referred to as a leveraged floater. When L is less than 1, the structured note is called a deleveraged floater. That is, the coupon rate for a deleveraged floater is computed as a fraction of the reference rate plus the quoted margin. Bankers Trust issued such a floater in April 1992 that matured in March 2003. This issue delivered quarterly coupon payments according to the following formula: 0.40 × (10-year Constant Maturity Treasury rate) + 2.65% with a floor of 6%.

Step-Up Notes

Step-up notes are securities that have a have coupon rates that increase over time. These securities are called step-up notes because the coupon rates “step up” over time. For example, a 5-year step-up note might have a coupon rate that is 5% for the first two years and 6% for the last three years. Or, the step-up note could call for a 5% coupon rate for the first two years, 5.5% for the third and fourth years, and 6% for the fifth year. When there is only one change (or step up), as in our first example, the issue is referred to as a single step-up note. When there is more than one change, as in our second example, the issue is referred to as a multiple step-up note.

An example of an actual multiple step-up note is a 5-year issue of the Student Loan Marketing Association (Sallie Mae) issued in May 1994. The coupon schedule is as follows:

6.05% from 5/3/94 to 5/2/95

7.00% from 5/3/96 to 5/2/97

7.75% from 5/3/97 to 5/2/98

8.50% from 5/3/98 to 5/2/99

Dual-Indexed Floaters

The coupon rate for a dual-indexed floater is typically a fixed percentage plus the difference between two reference rates. For example, the Federal Home Loan Bank System issued a floater in July 1993 that matured in July 1996 whose coupon rate was the difference between the 10-year Constant Maturity Treasury rate and 3-month LIBOR plus 160 bp. This issue reset and paid quarterly.

Range Notes

For a range note, the coupon rate is equal to the reference rate as long as the reference rate is within a certain range at the reset date. If the reference rate is outside of the range, the coupon rate is zero for that period.

For example, a 3-year range note might specify that the reference rate is 1-year LIBOR and that the coupon rate resets every year. The coupon rate for the year will be 1-year LIBOR as long as 1-year LIBOR at the coupon reset date falls within the range as specified below:

If 1-year LIBOR is outside of the range, the coupon rate is zero. For example, if in Year 1 1-year LIBOR is 5% at the coupon reset date, the coupon rate for the year is 5%. However, if 1-year LIBOR is 6%, the coupon rate for the year is zero since 1-year LIBOR is greater than the upper limit for Year 1 of 5.5%.

Consider a range note issued by Sallie Mae in August 1996 that matured in August 2003. This issue made coupon payments quarterly. The investor received 3-month LIBOR plus 155 bp for every day during the quarter that 3-month LIBOR was between 3% and 9%. Interest accrued at 0% for each day that 3-month LIBOR was outside this range. As a result, this range note had a floor of 0%.

Inverse Floaters

Typically, the coupon formula on floaters is such that the coupon rate increases when the reference rate increases, and decreases when the reference rate decreases. However, there are issues whose coupon rates move in the opposite direction from the change in the reference rates. Such issues are called inverse floaters or reverse floaters.9

The coupon reset formula for an inverse floater is

K − L × (Reference interest rate)

When L is greater than 1, the security is referred to as a leveraged inverse floater.

For example, suppose that for a particular inverse floater K is 12% and L is 1. Then the coupon reset formula would be

12% − (Reference rate)

Suppose the reference rate is 1-month LIBOR, then the coupon formula would be

12% − (1-month LIBOR)

If in some month 1-month LIBOR at the coupon reset date is 5%, the coupon rate for the period is 7%. If in the next month 1-month LIBOR declines to 4.5%, the coupon rate increases to 7.5%.

Notice that if 1-month LIBOR exceeded 12%, then the coupon reset formula would produce a negative coupon rate. To prevent this, there is a floor imposed on the coupon rate. Typically, the floor is zero. There is also a cap on the inverse floater. This occurs if 1-month LIBOR is zero. In that unlikely event, the maximum coupon rate is 12% for our hypothetical inverse floater. In general, it will be the value of K in the coupon reset formula for an inverse floater.

Suppose instead that the coupon formula for an inverse floater whose reference rate is 1-month LIBOR is as follows:

28% − 3 × (1-month LIBOR)

If 1-month LIBOR at a reset date is 5%, then the coupon rate for that month is 13%. If in the next month 1-month LIBOR declines to 4%, the coupon rate increases to 16%. Thus, a decline in 1-month LIBOR of 100 bp increases the coupon rate by 300 bp. This is because the value for L in the coupon reset formula is 3. Assuming neither the cap nor the floor is reached, for each 1 bp change in 1-month LIBOR the coupon rate changes by 3 bp.

As an example, consider an inverse floater issued by the Federal Home Loan Bank System in April 1999. This issue matured in April 2002 and delivered quarterly payments according to the following formula:

18% − 2.5 × (3-month LIBOR)

This inverse floater had a floor of 3% and a cap of 15.5%.

How Inverse Floaters are Created Using Interest Rate Swaps An inverse floater can also be created when an investment banking firm underwrites a fixed-rate bond (corporates, agencies, and municipalities) and simultaneously enters into an interest rate swap for a time that is generally less than the bond's tenor. The investor owns an inverse floater for the swap's tenor, which then converts to a fixed-rate bond (the underlying collateral) when the swap contract expires. An inverse floater created using a swap is called an indexed inverse floater.

To see how this can be accomplished, let us assume the following. An issuer wants to issue $200 million on a fixed-rate basis for 20 years. An investment bank suggests two simultaneous transactions.

Transaction 1: Issue a $200 million, a 20-year bond in which the coupon rate is determined by the following rules for a specific reference rate:

For years 1 through 5: 14% – Reference rate

For years 6 through 10: 5%

Transaction 2: Enter into a 5-year interest rate swap with the investment bank with a notional principal amount of $200 million in which semiannual payments are exchanged as follows using the same reference rate:

Issuer pays the reference rate

Issuer receives 6%

Note that for the first five years, the investor owns an inverse floater because as the reference rate increases (decreases) the coupon rate decreases (increases). However, even though the security issued pays an inverse floating rate, the combination of the two transactions results in fixed-rate financing for the issuer:

From the investment bank via the swap: 6%

Rate issuer pays

To security holders: 14% − Reference rate

To the investment bank via the swap: Reference rate

Net payments

(14% − Reference rate) + Reference rate − 6% = 8%

Equity-Linked Structured Notes

An equity swap can be used to design a bond issue with a coupon rate tied to the performance of an equity index.

To illustrate how this is done, suppose the Universal Information Technology Company (UIT) seeks to raise $100 million for the next five years on a fixed-rate basis. UIT's investment banker indicates that if bonds with a maturity of five years were issued, the interest rate on the issue would have to be 8.4%. At the same time, there are institutional investors seeking to purchase bonds but are interested in making a play (i.e., betting on) on the future performance of the stock market. These investors are willing to purchase a bond whose annual interest rate is based on the actual performance of the S&P 500 stock market index.

The banker recommends to UIT's management that it consider issuing a 5-year bond whose annual interest rate is based on the actual performance of the S&P 500. The risk with issuing such a bond is that UIT's annual interest cost is uncertain since it depends on the performance of the S&P 500. However, suppose that the following two transactions are arranged:

- On January 1, UIT agrees to issue, using the banker as the underwriter, a $100 million 5-year bond whose annual interest rate is the actual performance of the S&P 500 that year minus 300 bp. The minimum interest rate, however, is set at zero. The annual interest payments are made on December 31.

- UIT enters into a 5-year, $100 million notional amount equity swap with the banker in which each year for the next five years UIT agrees to pay 7.9% to the banker, and the banker agrees to pay the actual performance of the S&P 500 that year minus 300 bp. The terms of the swap call for the payments to be made on December 31 of each year. Thus, the swap payments coincide with the payments that must be made on the bond issue. Also as part of the swap agreement, if the S&P 500 minus 300 bp results in a negative value, the banker pays nothing to UIT and this risk is usually hedged with a basis swap that pays a fixed or floating cash flow in return for receiving the return on the S&P.

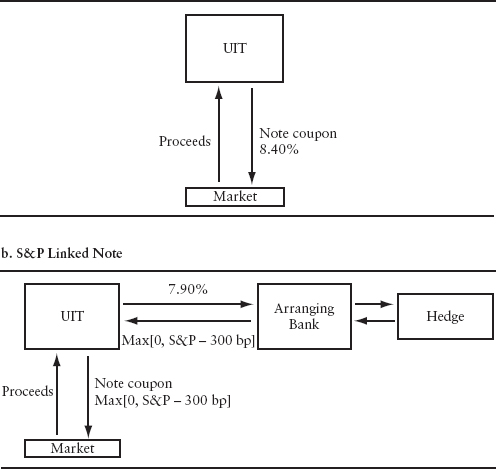

Exhibit 10.2 diagrams the payment flows for this swap. Consider what has been accomplished with these two transactions from the perspective of UIT. Specifically, focus on the payments that must be made by UIT on the bond issue and the swap and the payments that it will receive from the swap. These are summarized as follows:

| Interest payments on bond issue: | S&P 500 return – 300 bp |

| Swap payment from the banker: | S&P 500 return – 300 bp |

| Swap payment to the banker: | 7.9% |

| Net interest cost: | 7.9% |

EXHIBIT 10.2 Bond Structure: Conventional versus S&P Linked Note a. Conventional Bond Issue

Thus, the net interest cost is a fixed rate despite the bond issue paying an interest rate tied to the S&P 500. This was accomplished with the equity swap.

There are several questions that should be addressed. First, what was the advantage to UIT to entering into this transaction? Recall that if UIT issued a bond, the banker estimated that UIT would have to pay 8.4% annually. Thus, UIT has saved 50 bp (8.4% minus 7.9%) per year. Second, why would investors purchase this bond issue? In real world markets, there are restrictions imposed on institutional investors as to types of investment or by other portfolio guidelines. For example, an institutional investor may be prohibited by a client or by other portfolio guidelines from purchasing common stock. However, it may be permitted to purchase a bond of an issuer such as UIT despite the fact that the interest rate is tied to the performance of common stocks. Third, is the banker exposed to the risk of the performance of the S&P 500? In the swap market, there are ways for the banker to protect itself.

1 An extendible bond grants the issuer the right to extend the redemption date beyond the stated maturity date. A retractable bond grants the bondholder the right to redeem on a date prior to the original maturity date.

2 Karen McCann and Joseph Cilia, “Product Summary: Structured Notes,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, The Financial Markets Unit, Supervision and Regulation, November 1994, p. 6. This type of definition is one used by regulators of depository institutions. For example, in the instructions for Call Reports for banks, structured notes are defined as “debt securities, including all asset-backed securities except mortgage-backed securities and inflation-indexed Treasuries, whose cash flow characteristics (coupon rate, redemption amount, or stated maturity) depend upon one or more indices and/or that have embedded forwards or options or are otherwise commonly known as ‘structured notes.’”

3 Joel S. Telpner, “A Survey of Structured Notes,” The Journal of Structured and Project Finance 9 (Winter 2004), pp. 6–19.

4 Scott Y. Peng and Ravi Dattatreya, The Structured Note Market (Chicago: Probus, 1995), p. 2.

5 Peng and Dattatreya, The Structured Note Market, p. 2.

6 For example, a U.S. investor may want exposure to Japanese equities but not yen assets, so the investor can buy U.S. dollar-denominated bonds that have a payoff linked to the Japanese stock market index.

7 In the United States, a corporation that wants an MTN program will file a shelf registration with the SEC for the offering of securities. While the SEC registration for MTN offerings is between $100 million and $1 billion, once the total is sold, the issuer can file another shelf registration. The registration includes a list of the investment banking firms, usually two to four, that the corporation has arranged to act as agents to distribute the MTNs. The issuer posts rates over a range of maturities, typically as a spread over a benchmark such as a Treasury security of comparable maturity. The agents then make the offering rate schedule available to their investor base interested in MTNs.

8 Chapter 8 in Peng and Dattatreya, The Structured Note Market.

9 Inverse floaters in the mortgage-backed securities market are common and are created without the use of a derivative instrument by simply dividing a bond class into a floater and inverse floater at the time the deal is structured.