APPENDIX A

The Basel II Framework and Securitization

Banks and financial institutions are subject to a range of regulations and controls. Among the primary ones are concerned with capital adequacy, the level of capital a bank must hold to cover the risk of its many activities on and off the balance sheet. A capital requirements scheme proposed by a committee of central banks acting under the auspices of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in 1988 has been adopted universally by banks around the world. These are known as the BIS regulatory requirements or the Basel capital ratios, from the town in Switzerland where the BIS is based.1 Under the Basel requirements all cash and off-balance-sheet instruments in a bank's portfolio are assigned a risk weighting, based on their perceived credit risk, that determines the minimum level of capital that must be set against them.

A bank's capital is, in its simplest form, the difference between assets and liabilities on its balance sheet, and is the property of the bank's owners. It may be used to meet any operating losses incurred by the bank, and if such losses exceeded the amount of available capital then the bank would have difficulty in repaying liabilities, which may lead to bankruptcy. However, for regulatory purposes, capital is defined differently. In its simplest form, regulatory capital is comprised of those elements on a bank's balance sheet that are eligible for inclusion in the calculation of capital ratios. “Regulatory capital” includes equity, preference shares, and long-term subordinated debt, as well as the general reserves. The ratio required by a regulator will be that level deemed sufficient to protect the bank's depositors. The common element of these items is that they are all loss-absorbing, whether this is on an ongoing basis or in the event of liquidation. This is crucial to regulators, who are concerned that depositors and senior creditors will be repaid in full in the event of bankruptcy.

The Basel rules that came into effect in 1992 are popularly referred to as Basel I. Additional guidelines were published in final form in June 2004 with implementation set for 2006 to 2007 in Europe and 2008 to 2112 in the United States. These new guidelines are popularly referred to as Basel II. In this appendix, we present some highlights of the Basel II framework and offer some suggestions concerning its impact on securitization as well as credit derivatives.

BASEL RULES

A bank's total qualifying capital has two components: core capital, known as Tier 1, and supplementary capital, known as Tier 2. Tier 1 consists of the sum of three core capital elements minus goodwill. Those three elements are: (1) common stockholders' equity; (2) qualifying noncumulative perpetual preferred stock; and (3) minority interests in the equity accounts of consolidated subsidiaries. The Tier 1 component must represent at least 50% of total qualifying capital. Tier 2 consists of four supplementary capital elements: (1) allowances for loan and lease losses; (2) perpetual preferred stock; (3) hybrid capital instruments and mandatory convertible debt securities; and (4) term subordinated debt and intermediate-term preferred stock, including related surplus.

The Basel I rules set a minimum capital-to-assets ratio of 8% of the value of risk-weighted assets. Assets are categorized and value-adjusted based on their risk and the resulting risk-weighted assets are multiplied by 8%. For the purpose of this calculation, each asset on a bank's balance sheet is assigned a risk weighting and the risk-weighting percentages are grouped into four categories: Category 1, with a 0% risk weighting, includes a bank's own cash and claims on U.S government agencies and the central governments of OECD countries. Category 2, with a 20% risk weighting, includes cash items in the process of collection, short-term claims (including demand deposits) on U.S. and foreign banks, and long-term claims on U.S. and OECD banks. Category 3, with a 50% risk weighting, includes residential mortgages and mortgage-backed securities. Category 4, with a 100% risk weighting, includes commercial loans and other assets not included in the first three categories. So, for example, a loan in the interbank market would be assigned a 20% risk weighting, a loan of exactly the same size to a corporation would receive the highest weighting of 100%.

There are also risk weights for off-balance-sheet items. The face amounts of certain specified off-balance-sheet items are assigned conversion factors and the resulting credit-equivalent amounts are assigned to the appropriate risk category according to the obligor, such as a commercial bank or corporation. Guarantees and other direct credit substitutes have a 100% conversion factor. Transaction-related contingencies such as bid bonds, performance bonds, and standby letters of credit related to particular transactions have a 50% conversion factor. Short-term, trade-related contingencies such as commercial letters of credit have a 20% conversion factor. Finally, unused portions of commitments, such as lines of credit that are cancelable and have original maturities of one year or less, have a 0% conversion factor.

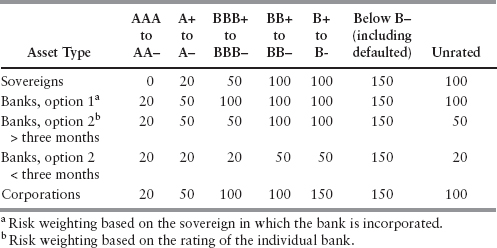

For interest rate and foreign exchange contracts such as swaps, credit-equivalent amounts are calculated and multiplied by credit conversion factors. The credit-equivalent amount for an off-balance-sheet interest-rate or exchange-rate instrument is the sum of its mark-to-market value and the potential future credit exposure over its remaining life. The potential future credit exposure is estimated by multiplying the instrument's notional principal amount by the appropriate credit conversion factor, as defined in the table below:

The resulting total credit-equivalent amount for the interest-rate or exchange-rate contract—the mark-to-market value plus potential future credit exposure—is assigned a risk weight according to the counterparty, such as a commercial bank or a corporation.

The perceived shortcomings Basel I attracted much comment from academics and practitioners alike, almost as soon as they were adopted. The main criticism was that the requirements made no allowance for the credit risk ratings of different corporate borrowers, and was too rigid in its application of the risk weightings. Recognizing how valid these concerns were, the BIS published proposals to update the capital requirements rules in 1999. The new guidelines are designed “to promote safety and soundness in the financial system, to provide a more comprehensive approach for addressing risks, and to enhance competitive equality.”

Basel I was based on very broad counterparty credit requirements, and despite an amendment introduced in 1996 (covering trading book requirements), remained open to the criticism of inflexibility. The proposed new Basel II rules have three pillars, and are designed to be more closely related to the risk levels of particular credit exposures. These are:

Pillar 1: New capital requirements for credit risk and operational risk.

Pillar 2: The requirement for supervisors to take action if a bank's risk profile is high compared to the level of capital held.

Pillar 3: The requirement for greater disclosure from banks than before to enhance market discipline.

With respect to Pillar 1, the capital requirements are calculated using one of two approaches—the standardized approach and the internal ratings based (IRB) approach. In the standardized approach, also known as the basic indicator approach, banks will risk-weight assets in accordance with a set matrix, which splits assets according to their formal credit ratings. Within the IRB approach there is a foundation approach and an advanced measurement approach, the latter of which gives banks more scope to set elements of the capital charges themselves. In the IRB approach banks categorize assets in accordance with their own internal risk assessment. For a bank to undertake this approach, its internal systems must be recognized by its relevant supervisory body, and its systems and procedures must have been in place for at least three years. The bank must have a system that enables it to assess the default probability of borrowers.

In the United States, only the top dozen or so large international banks are required to adopt Basel II and a few more are expected to adopt the standards voluntarily. They will use the advanced measurement approach to calculate their minimum capital requirements. Other U.S. banks will continue to follow Basel I. In Europe, all financial institutions, regardless of size and complexity, must adopt Basel II, but they are free to choose which approach they take. European banks taking the standardized, basic-indicator approach or the foundation approach must comply by the end of 2006 and those taking the advanced measurement approach must comply by the end of 2007. The U.S Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Office of Thrift Supervision approved new capital and risk management standards for U.S. banks under the Basel II framework in March 2006, setting a 4-year transition period starting in 2008 and also setting specific limits on any reduction in banks' risk-adjusted capital that may result from following the new guidelines. Even when Basel II is fully implemented, U.S. banks will be subject to regulators' minimum leverage ratio requirements and prompt corrective action rules. The bank regulatory agencies will prevent capital at large banks adopting Basel II from dropping more than 5% per year for three consecutive years. Also, if the aggregate level capital for all Basel II banks in the United States drops more than 10%, the regulators have said that they will reexamine the entire process.

It is generally believed that banks adopting Basel II will have a competitive advantage over banks continuing to follow Basel I because the advanced measurement approach will allow them to justify thinner capital charges than those allowed by formulas prescribed in the standardized approach. U.S. regulators plan to limit the competitive disadvantages for banks that do not follow Basel II in a new set of guidelines known as Basel IA.

Compared to the Basel I rules, general market opinion holds that the Basel II rules are an improved benchmark for assessing capital adequacy relative to bank risk. For the IRB framework, a significant change was the decision to base the capital charges for all asset classes on unexpected loss (UL) only, and not on both UL and expected loss (EL). In other words, banks must hold sufficient reserves to cover EL, or otherwise face a capital penalty. This move to an UL-only, risk-weight arrangement should result in the alignment of regulatory capital more closely with banks' actual economic capital requirement levels. A UL-only framework should result in banks regarding their capital base in a different light but should leave overall capital levels the same. The EL portion of risk-weighted assets is part of total eligible capital provision; and any shortage in eligible provisions will be deducted in a proportion of 50% from Tier 1 capital and 50% from Tier 2 capital. So the definition of Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital has changed under Basel II; the final framework withdraws the inclusion of general loan loss reserves in Tier 2 capital and excludes expected credit losses from required capital.

Note that the desire of the BIS to leave the general level of capital in the system at current levels means that a “scaling factor” can be applied to adjust the level of capital. This scaling factor has not been determined but will be assessed based on data collected by the BIS during the parallel running period. It will then be applied to risk-weighted assets to adjust for appropriate levels of credit risk.

The building blocks of the IRB approach are the following four measures of individual asset credit risk levels:

- Probability of default (PD): Measure of probability that the obligor defaults over a specified time horizon.

- Loss-given-default (LGD): The amount that a bank expects to incur in the event of default (a cash amount measure per asset, showing value-at-risk (VaR) in the event of default).

- Exposure-at-default (EAD). Bank guarantees, credit lines, and liquidity lines and is the forecast amount of how much a borrower will draw upon in the event of default.

- Remaining maturity of an asset (M): Assuming that an asset with a longer remaining term to maturity will have a higher probability of experiencing default or other such credit event compared to an asset of shorter maturity.

Under the advanced IRB approach, a bank is allowed to calculate its own capital requirement using its own internal measures of PD, LGD, EAD, and M. These are calculated by the bank's internal model using historical data on each asset, plus asset-specific data.2

Basel II allows adjustments to capital requirements for credit risk mitigation mechanisms such as netting, guarantees, credit derivatives, and collateral. However, in order to recognize these credit risk mitigants for risk-based capital requirements, the institution must have operational procedures and risk management processes to ensure that all documentation used in collateralizing or guaranteeing a transaction is legal and enforceable under applicable law in relevant jurisdictions, and the institution must have conducted sufficient legal review to reach a well founded conclusion that the documentation meets this standard.

A separate regime will require banks following Basel II to set aside capital to cover operational risk, the risk of loss from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, and systems or from external events—including legal risk but excluding strategic or reputational risk. A bank operating under the advanced measurement approach for operational risk can use a standardized approach or an IRB approach. A bank using the IRB approach must have an operational risk data and assessment system that incorporates internal operational loss event data, external operational loss event data, results of scenario analyses, and assessments of the bank's business environment and internal controls.

A financial institution's total qualifying capital under Basel II will be essentially the sum of Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital elements as in Basel I with a few exceptions. The allowance for loan and lease losses will be removed as a Tier 2 capital element and replaced with a methodology for adjusting risk-based capital requirements based on a comparison of the institution's eligible credit reserves with its expected credit losses. An institution's total risk-weighted assets will be the sum of its assets risk weighted for credit risk and operational risk minus the sum of its excess eligible credit reserves (eligible credit reserves in excess of its total expected credit losses) not included in Tier 2 capital.

IMPACT ON SECURITIZATION AND CREDIT DERIVATIVES

We now offer some suggestions on the possible impact of Basel II on securitization and credit derivatives.

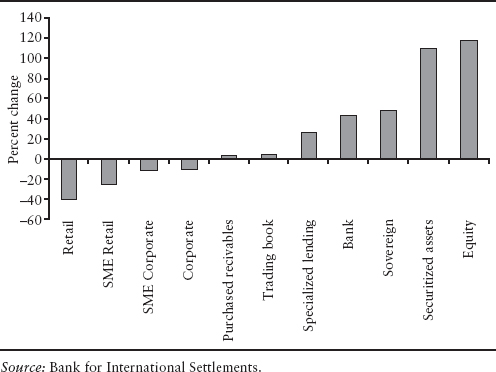

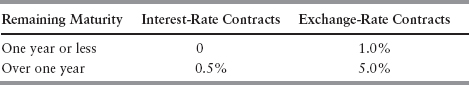

Exhibit A.1 shows the new risk categories for capital allocation under the new accord's IRB approach. Basel II recognizes that different types of assets behave differently, and is much more flexible than Basel I in this respect. Basel II provides specific capital calculation formulae for the following three asset types in a banking book: corporations, commercial real estate and retail. Different asset classes will be subject to different capital requirements under Basel II: Exhibit A.2 shows the BIS's own estimate of the change in requirements for Basel II compared to Basel I.

EXHIBIT A.1 Basel II Counterparty Risk Weights

EXHIBIT A.2 Basel II Capital Requirements for Different Asset Classes: Percent Change versus Basel I

Under Basel I, banks had a great incentive to enter into credit derivative contracts because of the impact on their balance sheets and the reduced cost of capital that resulted. Under Basel II, some of this incentive may be reduced; for instance, banks would not necessarily need to buy credit protection on high-credit-quality corporate loans. For example, in Exhibit A.1, the risk weight of a loan to a corporation rated at AA would be 20%. Buying credit protection on this loan from an AA-rated bank would not reduce this charge, while buying protection from an A-rated bank would actually increase the charge, to 50%.

The same impact may be observed in the structured product market, as the incentive to securitize certain assets is also reduced. When first aired, the Basel II proposals were expected to have a significant impact on the securitization market but this is not so evident on final publication. There is now a common hierarchical approach to the calculation methodology that is applied under the IRB approach to determine risk-weighting for a securitization transaction. This applies irrespective of whether a bank is the originator or an investor in the transaction. Essentially, however, there is a uniform treatment of securitization transactions. For use with the ratings-based approach, there is a set of appropriate risk-weights to use to calculate the weightings in a securitization deal.

Unlike the proposed framework for wholesale and retail exposures, the securitization framework proposed in Basel II does not permit a bank to rely on its internal assessments of risk related to securitization exposures. The proposed securitization framework in the U.S. Federal Reserve Board's April 2006 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPR) relies on two sources of information, to the extent available, to determine risk-based capital requirements: (1) a credit rating from a Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organization, i.e., a major credit rating agency such as Fitch, Moody's, or Standard & Poor's; or (2) risk-based capital requirements for the underlying exposures as if the exposures had not been securitized. The NPR suggests three general approaches for determining the risk-based capital requirements for securitization exposures: a ratings-based approach, an internal assessment approach, and a supervisory-formula approach. An institution is expected to apply a specified hierarchy of these approaches to determine the risk-based capital requirements for its securitization exposures.

An important objective of Basel II, with its closer alignment of regulatory capital to risk, is to address some of the capital arbitrage strategies that developed under Basel I. Because Basel I applies a flat 8% capital charge on all corporate assets, irrespective of the underlying credit quality of the borrower, the regulatory capital requirements on high-quality corporate assets were generally believed to be higher than the level of capital required to cover the economic risk of those assets. Therefore, Basel I gave banks an incentive to remove high-quality assets from their books by securitizing them. But originating banks often held on to the riskiest first-loss positions to help support their deals. So, even though they reduced their Basel I capital requirements, they did not necessarily reduce their economic risk exposure. By aligning regulatory capital on unsecuritized assets more closely to underlying economic risk than Basel I, Basel II reduces the incentives for banks to securitize loans to high-quality borrowers. Basel II also stems regulatory arbitrage by applying relatively stringent regulatory capital charges on junior securitization tranches, so banks will face higher costs if they retain those positions as credit enhancement for structured transactions. For example, for a bank using the standardized approach, unrated securitization positions must be deducted from capital—in other words the bank must set aside capital equal to that unrated securitization position.

For IRB banks that originate securitizations, a key element of the framework is the calculation of the amount of capital that the bank would have been required to hold on the underlying pool had it not securitized the exposures. This amount of capital is known as KIRB. If an IRB bank retains a position in a securitization that obliges it to absorb losses up to or less than KIRB before any other holders bear losses (i.e., a first-loss position), then the bank must deduct this position from capital. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision believes this requirement is warranted in order to provide strong incentives for originating banks to shed the risk associated with highly subordinated securitization positions that inherently contain the greatest risks. For IRB banks that invest in highly rated securitization exposures, a treatment based on the presence of an external rating, the granularity of the underlying pool (the number and diversity of the underlying exposures), and the thickness of the exposure (the dollar amount of the tranche) has been developed.

We surmise that there may be regulatory capital advantages to securitizing lower-rated assets to a greater extent than has been seen hitherto. This is because under the new ratings-based approach (see Exhibit A.1), under certain circumstances very low-rated assets, for instance below BB, attract a very high risk weighting. It remains to be seen what structured products arise to meet this potential requirement.

1 Bank for International Settlements, Basel Committee on Banking Regulations and Supervisory Practice, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, July 1988.

2 The calculation method itself is described in Basel II. However, a bank will supply its own internal data on the assets. This includes the confidence level: The IRB formula is calculated based on a 99.9% confidence level and a 1-year time horizon. This means there is a 99.9% probability that the minimum amount of regulatory capital held by a bank will cover its economic losses over the next 12 months. Put simply, that means that statistically there is only a 1 in 1,000 chance that a bank's losses would completely erode its capital base, assuming that this was kept at the regulatory minimum level.