APPENDIX D

Municipal Future-Flow Bonds in Mexico: Lessons for Emerging Economies

JAMES LEIGLAND

JAMES LEIGLAND

is a senior municipal finance advisor at the Municipal Infrastructure Investment Unit in Midrand, South Africa. [email protected]

In late August 2003, a small group of South African municipal officials and their advisors visited Mexico for a week to learn about recent developments in the Mexican municipal bond market. The trip, financed by the South African government, reflects a growing interest among developed as well as developing countries in a surprisingly sudden blossoming of the municipal bond market in Mexico. Beginning with no previous experience in municipal bond issuance, the Mexican market registered 10 municipal or state bond issues in less than two years, beginning in December 2001, with many more issues in preparation by the end of that period. The country now boasts a higher percentage of state and local governments with credit ratings from agencies like Fitch, Standard & Poor's, and Moody's than any other country except the United States. International donors and development finance institutions now regularly cite Mexico as an emerging economy that clearly is leading the way in terms of innovative municipal finance.

The Mexico case has generated considerable interest in a country like South Africa, which had a municipal bond market of sorts for decades before it became dormant in the early 1990s. Since the end of the apartheid government in 1994, the country has begun to focus on the massive numbers of formerly disenfranchised South Africans who still do not have access to basic municipal services. Borrowing directly from the capital markets appears to be an essential element of any successful nationwide effort to close the municipal infrastructure investment gap. However, neither issuers nor investors in South Africa have demonstrated much enthusiasm for municipal bonds.

This article reviews developments in the Mexican municipal bond market, and explains how legal and regulatory reforms in the country adapted innovative private-sector financing techniques, like future-flow securitization, to pave the way for a small, but active municipal bond market. The question of whether or not such an approach can or should be used in other developing countries is explored, with special reference to South Africa. This article concludes by suggesting that in many countries, the specific techniques used in Mexico may not be cost-effective, but the basic principles underlying the financial mechanics clearly have application.

MEXICO IN THE LATE 1990s

The 1994-95 financial crisis in Mexico led the federal government to take stock of its public financial health. Among many other things, government officials began to look for better ways of financing investments by state and local governments. The existing method involved loans by development and commercial banks backed by intercepts of intergovernmental tax-sharing grants, known as “tax participations.” Loan agreements typically allowed creditors, in case of default, to request the federal government to deduct debt-service payments from the borrower's monthly tax participation payments. The deduction amounted to an intercept of payments, executed by federal authorities, before the funds were transferred to the state or local borrower.

The intercept arrangement created an implicit federal guarantee of state and local borrowing, and a massive contingent liability for the federal government, at least in the eyes of lenders. This in turn meant that lenders paid little attention to the purpose of the borrowing or the credit standing of the borrower—all such loans were considered to be backed by the federal government's creditworthiness. The moral hazard associated with this kind of lending was significant.

The federal government began a series of reforms in the late 1990s designed to increase the financial autonomy and accountability of state and local entities by making clear that new debt no longer could be viewed as a risk of the federal government. Beginning in March 2000, no state or municipal debt would be backed with the tax-sharing intercept mechanism. Tax-sharing grants would continue to be made to states and municipalities, but borrowers and lenders would have to create new arrangements to secure repayment with no further direct federal involvement in the intercepts or any implication of federal guarantees. Requirements for bank capitalization also were changed, motivating banks to pay attention to the credit standing of their local government borrowers by seeking two ratings from nationally recognized credit rating agencies before making loans.

The reforms caused concern among lenders and borrowers alike because of other government reforms underway that were increasing the need for state and municipal borrowing. By the late 1990s, the government's fiscal decentralization program was in full stride. Between 1994 and 2001, the state and municipal government share of all public expenditure grew from 47% to 64%, reflecting the decision by federal officials to require those government entities to do more of the work in financing and managing government programs (Protego [2003]).

At the same time, a substantially new class of lender was emerging in the market—one with a rapidly growing need for long-term, high-quality, fixed-income debt denominated in local currency. In the late 1990s, the federal government privatized the management of its mandatory pension funds for private-sector employees. The new fund managers, known as afores, quickly transformed the funds into fast-growing pools of cash in need of good-quality investments. From 1998 to 2001 the assets managed by the afores increased by almost 600%, with the total expected to reach 20% of GDP by 2015 (Protego [2003]). In allowing these funds to invest in municipal bonds of at least single-A quality (as determined by two rating agencies), the government created instant demand for state and municipal securities of strong credit quality.

However, after the end of active federal involvement in the interception of tax-participation grants to states and municipalities, the challenge was to find some other way of enhancing the credit quality of debt issued by those entities. U.S.-style general obligation borrowing, backed by the full faith and credit of local governments, was not attractive to investors because the short terms of local elected officials (three years with no possibility of reelection) gave rise to worries that promises to pay debt service might be amended or retracted for political reasons. Revenue bonds, backed by the revenues from projects to be built with bond proceeds, were even less attractive because the years of reliance on tax-participation grants to back borrowing had allowed state and local officials to ignore the need for improvements in local revenue generation and collection. State and municipal services often were not managed efficiently and the revenues from those services usually were not dependable sources of debt repayment.

The tax-participation grants remained a large and predictable source of revenue, accounting for over 90% of state revenues and over 70% of municipal revenues (Fitch [2002]). The challenge was to find a way of convincing investors that state and local officials would be willing to use those revenues to repay debt in future situations where money was tight and new decision makers were tempted to withhold payments for projects approved by their predecessors.

FUTURE-FLOW SECURITIZATION

An idea for a solution came from the future-flow securitizations that allowed public and private companies in below-investment-grade countries to access affordable international finance. In traditional asset-backed securitizations, lenders repackage existing pools of home mortgages or car loans for resale as tradable securities. Credit card securitization is one of several variations of the asset-backed technique, in which both existing and future receivables are sold to a trust that in turn issues securities to investors. The receivables are associated with particular identified accounts, but also include future receivables that are generated through those accounts. In a sense, these are future flows, although generated by accounts specified at the initial closing, and typically the securities held by investors are backed by an equal amount of receivables. For these reasons, credit card securitizations are usually considered to be asset backed.

True future-flow transactions are usually transactions in which a borrower (referred to as the “originator”) raises funding on the basis of expected future sales. Because these are expected rather than existing sales (or existing, identified accounts), the outstanding principal amount of the securities is not always exactly equivalent to the outstanding principal amount of the underlying receivables. This quality makes them “future-flow” rather than “asset-backed” securitizations (Rough [2000]).

The first major future-flow securitization in a developing country was structured in Mexico by Citibank in 1987. It involved the securitization of telephone service receivables owed to Mexico's monopoly phone company, Telmex. The receivables arose when Telmex completed more calls for AT&T customers calling into Mexico than AT&T completed for Telmex customers calling into the U.S. The net international settlement receivables paid by AT&T to Telmex were relatively easy to estimate based on market history.

Telmex isolated debt-service payments to bond holders from any possibility of misdirection by company or government officials by selling the receivables to a U.S.-based trust, and instructing AT&T to pay its Telmex invoices to the trust, thus generating secure revenues for the holders of the securities (trust certificates) sold by the trust to investors. As the securities amortized, the residual liquidated receivables flowed back to Telmex. The future-flow mechanism represented a way for Telmex to issue investment-grade bonds at a time when Mexico was restructuring its sovereign debt, and Mexican companies, particularly state-owned enterprises, were unable to access international capital markets.

The Telmex deal was copied many times by many different kinds of companies. The number of such deals increased sharply after Mexico's 1994-95 crisis, with Latin American countries dominating the market. A key reason the future-flow mechanism became so popular so quickly in countries at or below investment grade was that the deals proved to be exceptionally resilient, even in situations of severe national economic distress. For example, in 1999 Pakistan defaulted on its sovereign debt, but an offshore trust continued to pay debt service on US$250 million in Pakistan Telecommunications Company bonds backed by future telephone-settlement receivables. According to Ketkar and Ratha [2001], by the end of 2001, the principal rating agencies reported having rated more than 230 future-flow deals worth more than $44 billion.

APPLICABILITY TO MEXICO

Although such deals vary greatly depending on types of collateral, legal and regulatory frameworks, and operational characteristics of the originators (borrowers), they share many common features, most of which were attractive to Mexican officials interested in finding a mechanism to help states and municipalities access the domestic capital market:

- Future-flow securitizations typically are driven by the need for capital market access by a company located in a developing country where a low sovereign rating (at the bottom of or below investment grade) capped the maximum rating that the company could earn. Mexican municipalities had a similar problem in the sense that their own low ratings tended to cap the ratings of their individual investment projects.

- In future-flow deals, the borrowing company normally has significant, dependable foreign-currency export receivables owed to it by creditworthy customers in other countries, who are able to pay in hard currency, usually U.S. dollars. Mexican municipalities had a significant, dependable source of domestic currency in the form of tax-participation grants. Federal reforms had made grant flows highly predictable via transparent formulas formalized in national legislation.

- In future-flow deals, the company establishes some form of special purpose vehicle (SPV), often a trust, in a tax-neutral jurisdiction outside the company's home country, where the court system is trusted by investors. The shift in jurisdiction helps ensure that the trust arrangements cannot be restructured easily. SPVs were not a new concept in Mexico. Federal officials were willing to authorize states and localities to create trusts that could handle debt service outside of the normal local government budget process. States and municipalities also were allowed to enter into debt covenants that would make any premature unwinding of trust arrangements particularly difficult.

- In future-flow deals, the company sells its existing and future export receivables to the trust in return for an upfront purchase price. In Mexico, federal officials did not want state and local authorities to actually securitize their debt in this sense because they wanted local entities to remain fully responsible for their obligations, but they were willing to allow local officials to pledge their tax-participation revenues to “administrative” trusts in exchange for loans.

- In future-flow deals, customers are given irrevocable instructions to pay their invoices to a collection account in which the trustee has a security interest for the benefit of the owners of the trust certificates. In Mexico, federal officials were willing to accept irrevocable instructions from local officials and legislatures to make tax-participation payments to administrative trusts rather than directly to the relevant state or municipality.

- In future-flow deals, the trust finances the purchase of future receivables by issuing securities subject to a series of stringent covenants with bondholders. In June 2001, Mexican federal government officials allowed states and municipalities to begin issuing securities similar to the bonds or commercial paper involved in most future-flow deals. Exchange certificates (certificados bursatiles) were introduced as direct, negotiable municipal debt instruments that, unlike the simple promissory notes traditionally used in Mexico for state and local borrowing, could include covenants, specify events of default, identify different maturity dates and amortization schemes, etc.

- Future-flow deals are particularly subject to “collateral performance risk,” the risk that in almost any portfolio of future receivables some customers will become delinquent or even default on payments (Roever and Fabozzi [2003]). Accordingly, the trust is often over-collateralized with several times more receivables pledged than are actually required to back the securities, in order to provide investors with a layer of protection against non-payment by customers, variations in the value of the exports, or other unexpected changes in anticipated revenues. In Mexico, because secure federal grants constitute such a high percentage of state and municipal revenues, over-collateralization was a feasible way to reassure investors against unanticipated reductions in intergovernmental grant flows.

ARGENTINA: AN EARLY TEST OF THE METHODOLOGY

A handful of municipal future-flow deals in Argentina during the late 1990s provided some key lessons for Mexican officials. Several Argentine provinces issued bonds backed by future streams of federal tax-sharing revenues. For example, in August 1997 Tucumán Province issued $200 million in seven-year bonds over-collateralized by a pledge of 35% of its total tax-sharing revenues. The revenues were transferred on a daily basis by the Argentine federal government to a local bank acting as a collection agent. The funds then were exchanged into U.S. dollars and transferred to a New York-based trust that made debt service payments.

Technically, this was not a future-flow securitization, because the flows were not securitized and sold to a trust. The province continued to “own” the revenue streams and remained fully responsible for the debt obligation. But Argentine officials successfully simulated key aspects of the securitization technique. For example, the fact that the debt was over-collateralized by tax-sharing revenues was recognized as a credit strength by the rating agencies.

Other features of the deal made rating agencies somewhat cautious, however. They were particularly concerned that government officials had not done enough to isolate the revenues from potential government interference. The province explicitly maintained the right to dissolve the trust arrangement if the province itself first declared an economic emergency. The deal also included a cross-default provision that required acceleration of bond repayments in the event that other, unsecured provincial debt defaulted. In the view of the rating agencies, all of this tied the revenue flows too closely to national and provincial government performance and processes. As a result, the rating of the deal failed to pierce the sovereign rating ceiling. Fitch-IBCA assigned the issue a grade of “BB—,” a notch below the sovereign rating at that time.

The rating agency concerns were confirmed later during the Argentine financial crisis. After the national government defaulted on its sovereign debt, the tax-sharing bonds were downgraded to default status as well, because of the national government's intention to divert revenues from the provinces, devalue the currency, and restructure existing government debt. By declaring a financial emergency, the province was able to unwind the deal and regain control over whatever revenues still were flowing from the national government.

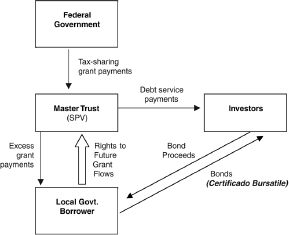

EXHIBIT 1

Municipal Future Flow Bonds: Flow of Funds

IMPLEMENTATION IN MEXICO

The Argentine experience with the tax-sharing future flows was instructive for Mexico. Mexican officials realized two things about the future-flow mechanism as a way to facilitate municipal bonds issuance: 1) the mechanism as used in Argentina could be perfected by using covenants to strengthen the isolation of revenue flows from potential government interference; and 2) when perfected, the mechanism offered a way of simulating the federal intercept arrangements that had made borrowing possible for Mexican states and municipalities prior to 2000. Instead of the federal government actively intercepting grant flows on behalf of lenders or investors, administrative trusts run by professional financial managers could receive grant revenues and make debt-service payments before local officials ever received the money. Accordingly, federal officials proposed that states and municipalities create administrative trusts into which tax-sharing revenues could be deposited directly by federal authorities, and out of which debt-service payments could be made directly to bond holders (see Exhibit 1).

The government entity could issue exchange certificates (certificados bursatiles), and use the trust to make debt-service payments, or the trust itself could sell “ordinary participation certificates” (certificados de participación ordinarios) and pay them off with tax-sharing revenues assigned to it by the state or local government. In this way, trusts could isolate debt-service payments from any general government expenditure accounts. As legal, tax-neutral entities under Mexican law, trusts could be created relatively easily by local officials, and professional financial managers hired to manage debt-service payments. So-called “master” trusts could allow management of several debt obligations at the same time, with funds going into designated sub-accounts.

Like the Argentine arrangements, Mexican deals stopped short of true securitization, although that term is sometimes used to characterize the deals (Standard & Poor's [2001]). The trust mechanism involved is a debt repayment vehicle only— an administrative trust rather than a guarantee trust. The debts managed by the trust remain direct obligations of the state or municipal borrower, whose revenues are used by the trust to make debt service payments. Those revenues are not packaged and sold to investors, as they would be in a future-flow securitization.

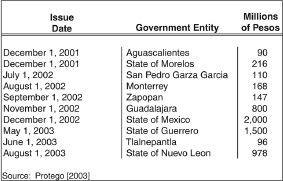

The use of such trusts quickly caught on, beginning in late 2000, with a number of Mexican states and municipalities using master trusts as payment mechanisms for infrastructure domestic currency bonds sold with relatively high ratings, low coupons, and terms ranging from five to seven years. Exhibit 2 shows bond issues involving trusts over the past two years.

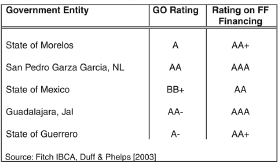

CREDIT ENHANCEMENT FEATURES

Perhaps the most important feature of the Mexican version of the municipal future-flow mechanism is its ability to assure rating agencies that they can give a higher rating to a municipal project than they would to the parent state or municipal government. Exhibit 3 compares Fitch's credit ratings on the five future-flow financings they had rated as of April 2003, with Fitch's general obligation ratings for the parent state or municipal entity benefiting from the trust financings. The rating differentials are dramatic, averaging an improvement of nearly five rating grades per deal.

The future-flow mechanism achieves these kinds of rating improvements because various features of the mechanism function as a web of sometimes overlapping internal credit enhancements to mitigate precisely the kinds of key borrowing risks that concern Fitch and the other credit rating agencies. It is no surprise that rating agencies respond favorably to this kind of structuring. Because issuers often target a particular rating as a desired outcome of the structuring process, they often attempt to engage rating agencies before the deal is structured. As a result, instead of reacting with a rating to a deal as it has been structured, rating agencies often advise issuers on enhancements for future-flow deals before the bonds come to market. With some early Mexican municipal issues, for example, rating agencies recommended less severe covenants in order to make events of default less likely.

EXHIBIT 2

Mexican State and Municipal Bond Issues

EXHIBIT 3

Ratings on Future-Flow Financings vs. Government-Obligation Ratings

The web of internal credit enhancements on municipal future-flow deals includes many of the key elements that make future-flow securitizations successful:

- The administrative trust structure provides enhancement by isolating the debt-service payment process from normal municipal budgets and expenditure processes. The money used to pay debt service is from a strong, reliable source, but it is especially attractive to investors because it does not pass through the hands of municipal officials—it cannot be diverted or withheld for political reasons.

- Additional credit enhancement results from irrevocable instructions to the federal government regarding deposit of tax-sharing grant revenues in the trust rather than with the municipality. In Mexico, these instructions often have been strengthened by being issued directly by state or local legislatures.

- Trusts are further strengthened with over-collateralization of debt, in the sense that the tax-sharing grant revenues pledged to support the outstanding debt, and secured in the trust's reserve accounts, typically are worth several times more than the par value of the debt itself. This surplus provides comfort to investors that in cases of under-performing tax revenues, or changes in federal allocation policies, a trust will still be able to repay bondholders.

Mexican officials have added several additional mechanisms to the future-flow technology to help avoid the kinds of problems evident in Argentina. The new types of securities authorized for use by Mexican municipalities make possible for the first time a variety of covenants with bondholders, and in Mexico covenants also provide a form of internal enhancement by requiring certain remedial actions by the trust to be triggered by different kinds of “credit events.” Remedial actions can include larger contributions to reserve accounts, the creation of additional reserve accounts to serve as a first line of defense against revenue problems, acceleration of debt repayment, or immediate repayment of all debt using all pledged revenues as they become available. Credit events can include rating downgrades, reductions in debt-service reserve accounts, or any other proxy for reduced revenue performance and increased bondholder risk.

Some covenants provide an extra measure of credit support with extreme penalties for breach. For example, any attempt by a municipality to re-take control of grant streams (e.g., via a court case to dissolve a trust) typically triggers full and immediate default. This kind of enhancement has been used in Mexico to assure investors that parent local governments will not attempt to unwind trust structures, as was done in Argentina during the national financial crisis.

VARIATIONS ON THE BASIC MODEL

One claim made for future-flow deals is that they help establish a credit history for borrowers, as well as market familiarity with municipal bonds (Chalk [2002]). All of this is expected to facilitate a gradual move to more traditional, less expensive borrowing techniques. In Mexico, there have been recent deals that make use of own-source municipal revenues rather than intergovernmental grants to back the borrowing. In this sense they are arguably more traditional, but the structuring involved is as aggressive—and expensive—as any deals seen in the market to date.

In Tlalnepantla de Baz, the most industrialized municipality in Mexico, a unique bond issue was sold in early 2003 backed by municipal revenues rather than federal tax-participation grants. To enhance the deal, a letter of credit for up to $5.3 million was issued in support of just over 50% of the borrowing by Dexia Credit Local, a development bank subsidiary of the Dexia Group, one of the largest financial groups in Europe. An additional 30% of the Tlalnepantla deal was backed by a municipal bond guarantee, worth up to $3 million, sold by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the first such guarantee ever offered by the IFC.

In Mexico, credit providers to municipalities must be Mexican-based companies. Because Dexia is not a Mexican-based company it could not guarantee bonds directly sold by the municipality. Instead, the bonds were sold by the trust established by Tlalnepantla, and the proceeds on-lent to the municipality. The external enhancements helped raise the local currency credit rating on the bonds from “AA” to “AAA,” without a sovereign guarantee or the backing of intergovernmental grant flows.

The Tlalnepantla de Baz bond issue represents perhaps the most innovative variation to date on the future-flow model. The inability to use tax-participation revenues to back the bonds stimulated the search for external credit enhancement—often used in future-flow securitization. The deal also made use of a so-called double-barreled pledge of revenues, often used in municipal bond issues sold in the U.S. market. The Tlalnepantla issue was backed primarily by revenues from the municipally-owned water utility. Should those revenues prove to be insufficient, municipal tax revenues of the parent municipality will provide a “second barrel” of support. The two underlying projects are also very much like what one would find financed by a U.S.-style revenue bond issue. Some bond proceeds will be used for the construction and operation of a wastewater treatment plant that will recycle wastewater for industrial re-use. The rest of the proceeds will be used to reduce physical and commercial water losses. In other words, the bond proceeds will be used directly for activities that eventually should pay for themselves.

A second variation on the Mexican municipal future-flow model, used in most of the early bond issues, involves the use of payroll tax revenues to back the borrowing. The State of Mexico sold such an issue in 2002, worth more than all previous municipal issues at the time. Other than the source of revenue for repayment, most of the rest of the deal is similar to earlier future-flow transactions, including a master trust, over-collateralization, etc. A debt-service reserve established at the time of issuance holds an amount equal to 10% of the principal. Covenants require that a second 10% reserve account be established in response to a variety of “credit events,” for example in the event that payroll tax revenues fall below minimum expected levels.

Like Tlalnepantla's water tariffs, payroll taxes are a local government revenue rather than intergovernmental grant income. However, as with intergovernmental grants, payroll taxes can be handled largely outside the local government expenditure process. Nationwide, approximately 85% of payroll tax revenues are collected by commercial banks, which can be given irrevocable instructions to turn those revenues over to administrative trusts established to handle debt-service payments for outstanding bond issues.

The state's congress issued a decree creating the trust and authorizing the issuance of irrevocable instructions to banks acting as tax collection agents. The decree formalized the trust mechanism in administrative law as well as in covenants with bondholders, thus adding to the legal strength of the arrangement. The various enhancements earned the deal a local currency rating of “AA,” at a time when the state's government obligation rating was just “BB+.” Mexico City (a federal district with the right to collect payroll taxes) has been working on a similar issue for several years.

COSTS AND RISKS

Mexican municipal future-flow bonds clearly constitute a powerful financing tool that has helped states and municipalities access badly needed capital at affordable interest rates. However, a variety of other kinds of significant costs and risks are associated with these mechanisms.

Transaction Costs

Although higher ratings reduce interest costs, the high fixed costs of these transactions can contribute to high overall borrowing costs. The deals are by definition highly structured and involve relatively long lead times and high transaction costs in the form of legal, banking, and management fees. The trust administration fees in Mexico also can be high. The International Monetary Fund (2003) estimates that the transaction costs on these kinds of deals are three to four times higher than on “plain vanilla” external bond issues. The complicated structure of these deals, and the practice of paying transaction costs from the proceeds of the bond issues, make the overall impacts of transaction costs much harder to evaluate than interest costs on the issue. In Mexico, the very heavy reliance of issuers on expensive advisors for due diligence, structuring, and underwriting has suggested to some local officials that whenever possible and practical, tasks be assigned separately so as to establish at least minimal checks and balances among advisors.

Enhancement Costs

Although attractive to investors, enhancements like over-collateralization are expensive ways to mitigate portfolio performance risks. The revenues pledged are much higher than normally are needed for debt service. This leaves less than usual to back future borrowing, potentially increasing the cost. The irrevocable nature of the pledge also makes any future debt restructuring difficult. Because of these high costs, it is clearly in the interests of the issuer that over-collateralization and other internal and external enhancements be used cost-effectively in optimizing the marketability of a bond issue. One method of encouraging this, employed on some Mexican deals, is to hire a specialized advisory firm to structure the issue, but not to do the underwriting. In that way, the deal structure can be optimized to suit the needs of the issuer, rather than the needs of investors who make up an underwriter's primary distribution network. The specialized advisor can help select an underwriter with experience and underwriting networks suited to the particular issue structure chosen.

Moral Hazard

Perhaps of most concern are the potential moral hazards associated with both the borrowing and lending activities involved in future-flow deals. Moral hazard was of course one of the reasons for the Mexican government's determination to end the implied federal government guarantee of local government borrowing. However, the future-flow mechanism clearly allows for several kinds of moral hazard to persist in the Mexican municipal debt market:

Over-borrowing. The mechanism can enable borrowing in situations where high interest rates might otherwise not allow it. A result of this is the temptation to over-borrow, by avoiding financing limits normally imposed by government policy or market discipline, and delaying needed improvements in financial management and other aspects of corporate governance.

Over-lending. Investors and lenders have little incentive to enforce normal market limits, because they bear very little risk in these deals. The various enhancements ensure that risk-sharing with lenders or investors is virtually non-existent. Lenders and investors are motivated to make capital available because the enhancements make the underlying credit strength of the issuer almost irrelevant.

Lack of Stakeholder Scrutiny. A third kind of moral hazard associated with these deals relates to the two above, but also derives from the unique and almost total separation in these deals between 1) the use of debt proceeds and 2) sources of revenue for debt repayment. In practice, this separation means that the purpose of the borrowing does not come under as much scrutiny as in other forms of borrowing.

- Revenue bonds of course closely link these two elements. Because the debt will be paid back from revenues generated by the investments to be made with bond proceeds, bondholders have an interest in the purpose of the borrowing. Government officials and the general public have a relatively clear indicator of the need for the borrowing and the rationale of the underlying project: if debt service is payable from project revenues, the deal has at least demonstrated financial self-sufficiency.

- In typical general obligation borrowing the link still exists, particularly in the minds of taxpayers. Such bonds are normally backed by local tax revenues, and have a direct impact on local tax rates. Consequently, taxpayers have an immediate interest in ensuring that the borrowing is necessary and cost-effective. This kind of municipal borrowing is the most closely monitored by citizens in a country like the United States.

- Locally issued debt backed by taxes set and collected at the national level weakens this link, and results in borrowing that few stakeholders have a strong interest in scrutinizing. Taxpayers have little incentive to monitor how the loan proceeds are spent locally, because their local projects—whether or not needed, well designed, or efficiently managed—have little impact on national tax rates. Taxpayer complaints about bond proceeds misspent on local projects typically do not lead to changes in national tax rates; the money is just spent on something else. Bondholders also have little incentive to monitor implementation if the bonds are secured with an over-collateralization of reliable tax revenues. In other words, responsible future-flow borrowing depends heavily on the integrity of local government officials, because there are few stakeholders looking over their shoulders.

Market participants in Mexico cannot point to specific examples of these sorts of moral hazards actually giving rise to serious problems, but there clearly is some concern in the marketplace that the potential for such problems exists.

APPLICABILITY TO OTHER EMERGING ECONOMIES: THE CASE OF SOUTH AFRICA

How applicable is the municipal future-flow mechanism to local government borrowing in other countries? This was the question asked by the South African local government officials and advisors who visited Mexico in late August 2003.

Similarities Between the Two Countries

The key municipal finance problem in South Africa is similar to the one affecting municipalities in Mexico and in many other emerging economies—not enough capital investment in municipal infrastructure. As in Mexico after the 1994-95 financial crisis, South African officials realized by the end of the 1980s that a perceived sovereign guarantee of local government borrowing was creating large contingent liabilities for the national government and retarding the development of a normal market in local government debt. A municipal bond market of sorts had existed for decades, but most of the debt was sold under the apartheid government's “prescribed investment regime,” which required institutional investors to hold 54% of their investment portfolios in a range of government securities, including municipal bonds.

The high, fixed percentage and an implied sovereign guarantee meant that virtually all municipal securities could be sold quickly via private placement to a relatively small number of institutional investors. The system fed capital to municipalities and helped to build and maintain Western-style urban infrastructure services for the white minority under apartheid, but encouraged little development of the market practices and investor skills associated with a viable municipal bond market. Investors were required to buy bonds, and bond proceeds were used to build infrastructure for white citizens who were mostly willing and able to pay for it (or other sources of revenue were found to repay bondholders). In other words, there was little incentive for lenders to do credit analysis, and agency credit ratings were unnecessary. There was virtually no trading of bonds; investors simply bought and held them to fulfill their portfolio requirements.

The prescribed regime ended in the early 1990s. Municipal bond sales stopped entirely (the last municipal bond issue listed on the Bond Exchange was sold by the City of Durban in 1993). Private bank lending to municipalities also began to decline after 1994, largely because municipalities were expanded to include disadvantaged areas and, as a result, became much less attractive to private sector lenders. Amalgamations dramatically increased the need for municipal infrastructure finance by formally bringing disadvantaged citizen inside municipal boundaries, but made municipal debt even less attractive to private banks because the added areas reduced average payment levels as well. In the eyes of many traditional commercial bankers, the creditworthiness of these municipalities declined sharply after 1994.

Like Mexico's parastatal development bank, Banobras, South Africa's Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBS A) was used by government to fill some of the infrastructure investment gap in the late 1990s. But like Banobras, DBSA could not supply all municipal investment needs, and its strong presence in the market was somewhat counterproductive because it tended to discourage private lenders from returning to the market and discouraged stronger municipalities from actively pursuing bond issues.

Key Differences

Unlike Mexico, South Africa could not identify innovative municipal financing techniques in the 1990s to replace the prescribed investment regime, and is unlikely to make use of the future-flow bond technology. The reasons for this reflect important differences between South Africa and Mexico, but also suggest that Mexico may not be as typical an emerging economy as its South African visitors hoped in August 2003.

Revenue. Without large, reliable revenue flows that can be intercepted before they enter the municipal bank accounts, there is little rationale for going through the expensive process of establishing privately managed trusts to isolate debt repayment from normal government decision-making. In Mexico, state and local governments have such flows because 88% of total state and municipal revenue comes from federal transfers. South African municipalities, on the other hand, receive just 17% of their revenue from intergovernmental grants (Republic of South Africa [2003]). The numbers mean that South African municipalities are more self-sufficient and have much stronger incentives to manage their affairs efficiently, but by the same token will not gain much by creating administrative trusts to enhance borrowing.

Legal Framework. Without a legal and regulatory framework that strongly and clearly sanctions the use of trusts and other internal credit enhancements in municipal borrowing, investors are likely to question the reliability of the future-flow mechanism. Partly because of the municipal future-flow bond experience in Argentina, Mexican authorities recognized early on that such arrangements must be firmly rooted in law to assure investors that trusts cannot be unwound or revenues diverted at some point in the future. In establishing such a legal and regulatory framework, national policy makers in Mexico also displayed a substantial measure of confidence in the integrity of local officials, because of the moral hazard potential described above. National government officials in South Africa, on the other hand, are concerned about the misuse of trusts and similar mechanisms by municipalities, particularly in terms of reduced financial accountability and transparency. Consequently, the government's new Municipal Finance Management Act, passed by the National Assembly in September 2003, prohibits the use of trusts by municipalities for purposes related to borrowing, and requires that all intergovernmental grant revenues be transferred directly into a “primary” municipal bank account.

Credit Ratings. Without market respect for agency credit ratings, and without the presence of the international rating agencies to provide authoritative ratings, it is difficult to gauge the value of the structuring that goes into a future-flow deal, and to know how much structuring is enough. A country in which many municipalities have ratings also tends to have more competition among lenders, some of which may not be willing or able to invest in their own in-depth credit analysis. Mexican officials took advice from World Bank experts in the late 1990s and encouraged banks to solicit two ratings every time they made a municipal loan. That helped attract the major international rating agencies to Mexico and helped poise them to play an active role in future-flow structuring. In South Africa, national officials have taken an approach that is much more common in the developing world. Detailed government data on municipal performance has not been released to the public, and ratings have not been encouraged, apparently out of a concern about embarrassing under-performing municipalities. In any case, the reliance on ratings in investment decision-making has been slow to take off in the South African capital market; credit ratings still represent only a minor factor in such decisions. Several local rating agencies exist in South Africa (including one affiliate of an international agency), but only one international firm has opened an office in the country.

Role of the Development Bank. For any kind of competitive, private-sector financing of municipalities to thrive, subsidized government “development banks” must be prevented from crowding out private-sector lenders or investors from deals involving the upper tier of creditworthy municipal borrowers. As the impressive recent history of bond issuance activity in Mexico confirms, the country's powerful development bank, Banobras, generally has been either unwilling or unable to crowd out private-sector lenders and investors. Indeed, Banobras recently has entered into a preliminary agreement with the IFC to develop mechanisms for insuring municipal bonds, presumably in recognition of the value of an active municipal bond market. In South Africa, the government's Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) is the most active lender to municipalities, but an overwhelming percentage of its funding (65%) goes to the six largest “metropolitan” municipalities such as Johannesburg, Durban, and Cape Town, effectively keeping those municipalities largely away from private commercial lenders, and completely out of the bond market (Republic of South Africa [2003]). Many market participants in South Africa, including many commercial banks, argue that DBSA strongly crowds the private sector out of municipal lending.

Market Size. Finally, of course, larger and more liquid markets attract more competition among purveyors of financial innovation and expertise. South Africa, with a population of 44 million, is not even half the size of Mexico (102 million). More important, Mexico has 31 states and 2,431 municipalities. Market participants expect that 150 of these local governments soon will have credit ratings and begin weighing various forms of borrowing, including future-flow bonds. The country's proximity to the United States ensures a steady and productive interaction among legal and financial experts on both sides of the border. In South Africa, the capital market is small, volatile, and isolated. The potential for municipal bond market activity is vastly smaller than in Mexico, with just 284 municipalities, including only one or two with the size or credit strength to access the capital market directly without extensive internal and/or external credit enhancement.

CONCLUSION: BACK TO BASICS

South African municipalities are unlikely to find significant value in Mexico-style municipal future-flow bonds. Indeed, such instruments do not appear to offer much help for the financing problems of municipalities in the many developing countries where the various special conditions that gave rise to the future-flow approach do not exist. However the Mexican model is useful in underscoring some basic principles of municipal bond market development.

The Role of National Government

The use of municipal future-flow bonds in Mexico is probably more a result of political will than the structuring innovations of legal and financial experts. The federal government made intergovernmental transfers a reliable and predictable source of local government revenue; introduced modern, flexible investment instruments; ensured that the legal/regulatory framework supported the use of trusts and the various other credit enhancements required by investors; strongly promoted the use of credit ratings; and condoned a more progressive stance toward municipal bond issuance by its own development bank. It is possible to argue that the federal government took this action only after the financial crisis of 1994-95 highlighted the weaknesses of the existing system of municipal finance, including the implicit federal government guarantee of municipal borrowing, and the government's resulting contingent liability. However, similar circumstances have not prompted many other developing country governments to such creative action. As is the case so often in the developing world, political will to act can have a profound impact on development, but is extremely rare. This is certainly the case with development of municipal bond markets.

The Role of Local Government

In addition to political will, Mexico displays another quality that is often a key missing ingredient in efforts to kick-start municipal bond markets—a willingness to give local government officials the benefit of the doubt when it comes to municipal borrowing. Decentralization is an often-expressed goal in the developing world, but when it comes to finance, national government officials often are unwilling to let their local government counterparts operate without close supervision. Municipal bond borrowing is an area of finance notorious for wasteful spending and corruption, even in so-called developed economies. Municipal future-flow bonds appear to increase the temptation to misbehave. Nevertheless, Mexican officials are to some extent giving the benefit of the doubt to local officials in an effort to promote innovative financing of municipal infrastructure. Critics in countries such as South Africa accuse national government officials of micro-managing local government affairs in an effort to eliminate every opportunity for corrupt behavior, but at the same time forestalling meaningful decentralized public finance. Mexico has far to go in improving the management and self-sufficiency of its municipalities, but that process has begun in notable fashion with a decentralized approach to borrowing.

Municipal Bond Market Basics

The structuring techniques involved in Mexico's municipal future-flow deals are mostly mechanisms for achieving in a nascent municipal bond market the kinds of minimally acceptable deal characteristics that often are taken for granted in more developed markets. Finding short cuts or proxies to achieve these kinds of characteristics, sometimes at significant risk and cost, is a common strategy in efforts to develop municipal bond markets in emerging economies (Leigland [1997]). Municipal future-flow bonds may not be cost-effective in South Africa's capital market, but whether or not the specific structuring techniques are appropriate, the basics that underlie the future-flow approach are essential to successful municipal bond sales in any market:

Ability to Pay. Municipalities must have revenue streams that are large and reliable enough to repay investors, and must be able to demonstrate convincingly to prospective investors that those revenue streams are thoroughly predictable. If intergovernmental grant flows are formalized and predictable, as they are in Mexico, they are often particularly attractive to investors because they do not depend on the ability of the municipality in question to carry out effective revenue management. Obviously, the more of such revenue that can be pledged for exclusive use in repayment of debt, the more comfortable investors are. This is the benefit of over-collateralization techniques used in Mexico.

Willingness to Pay. Municipalities also are expected to demonstrate that they will be willing to repay debts, regardless of changes in politicians or administrative personnel. However, the most convincing way to deal with this issue is not through elaborate promises to pay, but by showing that revenues needed to repay bondholders will be used for that purpose regardless of the intentions of officials. Various kinds of intercept mechanisms have been used, particularly in developing countries, to ensure that kind of repayment. The administrative trusts used in Mexico maximize the impact of the intercept concept by allowing all debt-service payments to be made before the revenues even reach municipal bank accounts. To ensure that municipal officials cannot redirect the revenues to the municipality, irrevocable instructions are given to depositors.

Binding Promises. Investors must be convinced that the various commitments to repay them are legally binding on the municipal issuer. This is accomplished through a variety of contractual promises, with painful sanctions for breach. Some Mexican local governments also have backed these commitments with formal resolutions of the local legislatures, thus recognizing the promises in administrative law as well. And of course legal opinions by reputable law firms are required on all of these arrangements.

Extra Enhancement. From the perspective of investors, there is no such thing as too much credit enhancement. As long as the costs of enhancements, including municipal bond insurance, are outweighed by savings achieved for the municipal issuer (e.g., in the form of lowered interest rates), such enhancements make financial sense.

REFERENCES

Chalk, Nigel. “The Potential Role for Securitizing Public Sector Revenue Flows: An Application to the Philippines.” IMF Working Paper No. 02/106. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2002.

Fitch IBCA, Duff & Phelps. “Financing of Mexican States, Municipalities, and Agencies: Alternatives and Strategies.” Fitch Ratings: Public Finance, January 31, 2002.

———. “Special Report: Boom Times at the Rio Grande: U.S.Mexico Border Region Expands.” Fitch Ratings: International Public Finance, May 1, 2003.

International Monetary Fund. “Assessing Public Sector Borrowing Collateralized on Future-flow Receivables.” Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, June 11, 2003.

Ketkar, Suhas, and Dilip Ratha. “Development Financing During a Crisis: Securitization of Future Receivables.” Policy Research Working Paper No. 2582. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2001.

Leigland, James. “Accelerating Municipal Bond Market Development in Emerging Economies: An Assessment of Strategies and Progress.” Public Budgeting and Finance, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Summer 1997).

Protego. “Development of the Mexican Bond Market for Sub National Governments.” Unpublished; Mexico City: Protego, August 2003.

Republic of South Africa. Intergovernmental Fiscal Review. Pretoria: RSA National Treasury, 2003.

Roever, W. Alexander, and Frank J. Fabozzi. “A Primer on Securitization.” The Journal of Structured and Project Finance, Vol. 9, No. 2 (2003), pp. 5-19.

Rough, Clive. “Future-flow Securitisation in Asia.” The Asian Securitisation and Structured Finance Guide 2000. London: White Page, January 2000.

Standard & Poor's. “Securitization of Federal Tax Participations by Mexican States and Municipalities.” Standard & Poor's RatingsDirect Research, May 17, 2001.

To order reprints of this article, please contact Dewey Palmieri [email protected] or 212-224-3675.

Copyright Institutional Investor, 225 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003.