CHAPTER 6

Cash Flow Collateralized Debt Obligations

The collateralized debt obligation (CDO) was a natural advancement of securitization technology, first introduced in 1988. A CDO is essentially a structured finance product in which a distinct legal entity, a special purpose vehicle (SPV), issues bonds or notes against an investment in cash flows of an underlying pool of assets. These assets include one or more of the following types of debt obligations:

- investment-grade and high-yield corporate bonds;

- emerging market bonds;

- residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS);

- commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS);

- asset-backed securities (ABS);

- real estate investment trusts (REIT) debt;

- bank loans;

- special-situation loans and distressed debt; and

- other CDOs.

When the underlying pool of debt obligations consists of bond-type instruments, a CDO is referred to as a collateralized bond obligation (CBO). These CDOs are classified as corporate bond-backed CDOs, emerging market-backed CDOs, and structured finance-backed CDOs. The collateral for the latter includes RMBS, CMBS, ABS, and REIT debt. When the underlying pool of debt obligations is bank loans, a CDO is referred to as a collateralized loan obligation (CLO).

Originally CDOs were developed as repackaging structures for high-yield corporate bonds and illiquid instruments such as certain convertible bonds, but they have developed into sophisticated investment management vehicles in their own right. Through the 1990s, CDOs were the fastest growing asset class in the ABS market, due to a number of features that made them attractive to issuers and investors alike. A subsequent development was the synthetic CDO, a structure that uses credit derivatives in its construction and is therefore called a structured credit product.

In this chapter we explain the basic CDO structure, the types of CDOs, and the motivation for creating a portfolio of CDOs. Our focus in this chapter is on cash flow CDOs. In the next chapter, we cover synthetic CDOs.

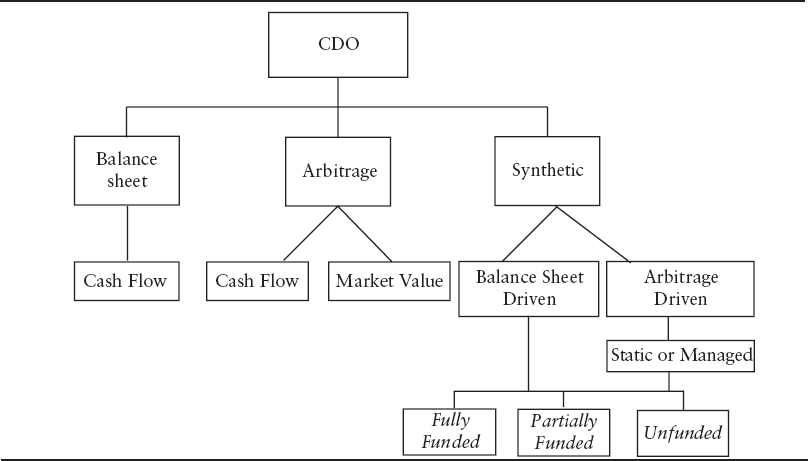

FAMILY OF CDOS

The CDO family is shown in Exhibit 6.1. The first distinction in the CDO family is between cash CDOs and synthetic CDOs. A cash CDO is backed by a pool of cash-market debt instruments. These were the original types of CDOs issued.

A synthetic CDO is a CDO where the investor has economic exposure to a pool of debt instruments, but this exposure is realized via a credit derivative rather than the purchase of the cash-market instruments.

Both a cash CDO and a synthetic CDO are further divided based on the motivation of the sponsor. The motivation is either “balance sheet” or “arbitrage.” As explained below, in a balance sheet CDO, the motivation of the sponsor is to remove assets from its balance sheet. In an arbitrage CDO, the motivations of the sponsor are (1) to gain a fee for managing the underlying pool of assets of the CDOs and (2) to capture a spread between the return realized on the collateral underlying the CDO and the cost of borrowing funds to purchase that collateral (i.e., the interest rate paid on the CDOs' debt).

Cash arbitrage CDOs are further divided into cash flow and market value CDOs depending on the credit protection mechanism that ensures repayment of the CDO's debt. In a cash flow CDO, the after-default interest, maturing principal, and default recoveries from the underlying assets provide CDO debt with credit protection. In a market value CDO, the ability of the CDO to realize sufficient proceeds from the sale of its assets to repay its debt provides the CDO debt with credit protection. There has been little issuance of market value CDOs since the 1980s. This is because sponsors who were motivated to use them for balance sheet management purposes generally stopped using them after a change in accounting rules in the 1990s. Our focus in this chapter is therefore on cash flow CDOs.

EXHIBIT 6.1 The CDO Family

BASIC STRUCTURE OF A CASH FLOW CDO

In a CDO, there is an asset manager responsible for managing the portfolio. The manager is referred to as the “CDO manager” or the “collateral manager.” There are restrictions imposed (i.e., restrictive covenants) as to what the CDO manager may do and certain tests that must be satisfied for the CDO securities to maintain the credit rating assigned at the time of issuance. We'll discuss some of these requirements later.

The funds to purchase the underlying assets or collateral (i.e., the bonds and loans) are obtained from the issuance of debt obligations. The total debt obligations for a given CDO are generally divided into several different classes or “tranches” (from the French word for “slice”), each with a different risk profile to suit different investor preferences. The tranches are generally ranked by seniority as follows:

- senior tranches;

- mezzanine tranches; and

- subordinate/equity tranche.

A rating will be sought for all but the subordinate/equity tranche. Senior tranches typically are rated AAA or AA. Mezzanine tranches typically are rated A through B. Since the subordinate/equity tranche receives the residual cash ?ow, no rating is sought for this tranche.

The ability of the CDO to make the interest payments to the tranches and pay off the tranches as they mature depends on the performance of the underlying assets. The proceeds to meet the obligations to the CDO tranches (interest and principal repayment) can come from (1) coupon interest payments from the underlying assets, (2) maturing assets in the underlying pool, and (3) sale of assets in the underlying pool.

To maintain the credit quality of the CDO's portfolio, trading restrictions are imposed to constrain the CDO manager's authority to buy and sell bonds. The conditions for disposing of assets are specified and usually are driven by credit-risk considerations. We will discuss these considerations later. Also, in assembling the portfolio, the CDO manager must meet certain requirements set forth by the agencies that rate the transaction.

There are three distinct periods in the life of a CDO. The first is the ramp-up period. This period usually begins two to six months before the closing date of the transaction and usually ends fewer than six months afterwards when the CDO manager completes the purchase of the CDO's initial portfolio. The reinvestment period or revolving period is when principal proceeds are reinvested in new collateral assets and usually is five to seven years long. In the final period, the portfolio assets mature or are sold, and the note holders are paid off as described next.

Distribution of Income

Income is derived from interest income and capital appreciation on underlying assets. The income is then used as follows: Payments are first made to the trustee and administrators and then for the CDO manager's senior fee. Once these fees are paid, the senior tranches are paid their interest. At this point, before any other payments are made, certain compliance tests must be passed. These tests are will be discussed later. If the compliance tests are passed, then interest is paid to the mezzanine tranches. Once the mezzanine tranches are paid, another set of compliance tests is conducted. If these compliance tests are passed, interest is paid to the subordinate/equity tranche. Such a distribution schedule is often called a waterfall.

In contrast, if either senior or mezzanine compliance tests are failed, then, depending on the CDO's structure and how severely those tests are failed, available income is used either to pay down senior tranche principal or purchase more collateral assets. If the senior tranches are paid off fully but mezzanine compliance tests are failed, then any remaining income after paying interest to the mezzanine tranche is used to redeem the mezzanine tranches. Only after senior debt and mezzanine debt are paid interest and any principal that is due as a result of the failure of the compliance test does any remaining CDO income flow to the subordinate/equity tranche.

During the life of the CDO transaction, a portfolio administrator will produce a periodic report detailing the quality of the collateral pool. This report is known as an investor or trustee report and also shows the results of the compliance tests that are required to affirm that the tranches of the CDO have maintained their credit ratings.

Distribution of Principal Cash Flow

Principal cash ?ow from CDO assets is distributed as follows after the payment of the fees to the trustees, administrators, and senior managers. If there is a shortfall in interest paid to the senior tranches, principal proceeds are used to make up the shortfall. Assuming that the compliance tests are satisfied during the reinvestment period, principal is reinvested. After the reinvestment period or if the compliance tests are failed, principal cash ?ow is used to pay down the senior tranches until the compliance tests are satisfied. If all the senior tranches are paid down, then the mezzanine tranches are paid off, and then the subordinate/equity tranche is paid off.

After all the debt obligations are satisfied in full, the subordinate/equity investors are paid. Typically, there are also incentive fees paid to management based on performance. Usually, a target return for the subordinate/equity investors is established at the inception of the transaction. Management is then permitted to share on some pro rata basis once the target return is achieved.

CDOS AND SPONSOR MOTIVATION

As can be seen in Exhibit 6.1, cash flow CDOs are categorized according to the motivation of their sponsors: balance sheet CDOs and arbitrage CDOs.

Balance Sheet CDOs

Cash flow CDOs are similar to other asset-backed securitizations involving SPVs. Bonds or loans are pooled together, and the cash flows from these assets are used to back the liabilities of the notes issued by the SPV into the market. As the underlying assets are sold to the SPV, they are removed from the originator's balance sheet; hence the credit risk associated with these assets is transferred to the holders of the issued notes

Banks and other financial institutions are the primary originators of balance sheet CDOs. These are deals securitizing banking assets such as commercial loans of investment-grade or subinvestment-grade rating. The main motivations for entering into this arrangement are:

- to obtain regulatory relief;

- to increase return on capital via the removal of lower yielding assets from the balance sheet;

- to secure alternative and/or cheaper sources of funding; and

- to free up lending capacity with respect to an industry or other category of borrowers.

Investors are often attracted to balance sheet CDOs because they are perceived as offering a higher return than say, credit card ABS, at a similar level of risk exposure. They also represent a diversification away from traditional ABS investments. The asset pool in a balance sheet CDO is static, that is, it is not traded or actively managed by a portfolio manager. For this reason the structure is similar to more traditional ABS or repackaging vehicles.

Arbitrage Motivated CDOs

A cash flow arbitrage CDO has certain similarities with a balance sheet CDO, and if it is a static pool CDO, it is also conceptually similar to an ABS deal.1 The priority of payments is similar, starting from expenses, Trustee and servicing fees, senior noteholders, and so on down to the most junior noteholder.

The key as to whether it is economically feasible to create an arbitrage CDO is whether a structure can offer a competitive return to the equity tranche.

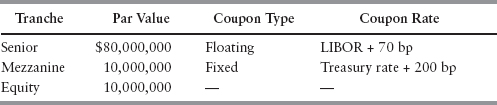

To understand how the equity tranche generates cash flows, consider the following basic $100 million CDO structure with the coupon rate to be offered at the time of issuance as follows:

Suppose that the collateral consists of high-yield bonds that all mature in 10 years and the coupon rate for every bond is the 10-year Treasury rate plus 400 bp. The CDO enters into an interest rate swap agreement with another party with a notional principal of $80 million in which the CDO agrees to do the following:

- Pay a fixed rate each year equal to the 10-year Treasury rate plus 100 bp

- Receive LIBOR

Keep in mind, the goal is to show how the equity tranche can be expected to generate a return.

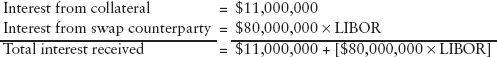

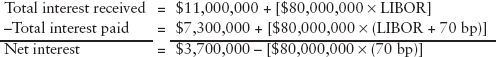

Let's assume that the 10-year Treasury rate at the time the CDO is issued is 7%. Now we can walk through the cash flows for each year. Look first at the collateral. The collateral will pay interest each year (assuming no defaults) equal to the 10-year Treasury rate of 7% plus 400 bp. So the interest will be

![]()

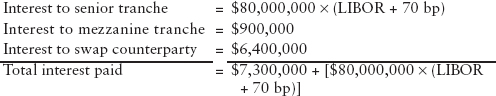

Now let's determine the interest that must be paid to the senior and mezzanine tranches. For the senior tranche, the interest payment will be

![]()

The coupon rate for the mezzanine tranche is 7% plus 200 bp. So, the coupon rate is 9% and the interest is

![]()

Finally, let's look at the interest rate swap. In this agreement, the CDO manager is agreeing to the swap counterparty 7% each year (the 10-year Treasury rate) plus 100 bp, or 8%. In our illustration because the notional principal is $80 million, the CDO manager selected the $80 million because this is the amount of principal for the senior tranche. So, the CDO manager pays to the swap counterparty:

![]()

The interest payment received from the swap counterparty is LIBOR based on a notional amount of $80 million. That is,

![]()

Now we can put this all together. Let's look at the interest coming into the CDO:

The interest to be paid out to the senior and mezzanine tranches and to the swap counterparty are:

Netting the interest payments coming in and going out we have:

Since 70 bp times $80 million is $560,000, the net interest remaining is $3,140,000 (= $3,700,000 – $560,000). From this amount, any fees (including the asset management fee) must be paid. The balance is then the amount available to pay the subordinate/equity tranche. Suppose that these fees are $614,000. Then the cash flow available to the equity tranche is $2.5 million. Since the tranche has a par value of $10 million and is assumed to be sold at par, this means that the potential return is 25%.

Obviously, some simplifying assumptions have been made. For example, it is assumed that there are no defaults. It is assumed that all of the issues purchased by the CDO manager are noncallable (or not prepayable) and therefore the coupon rate would not decline because issues are called. Moreover, after some period the CDO must begin repaying principal to the senior and mezzanine tranches. Consequently, the interest swap must be structured to take this into account since the entire amount of the senior tranche is not outstanding for the life of the collateral.

In fact, the poor collateral performance of CBOs backed by high-yield corporate bonds from 2000 to 2003 was further compounded by their interest rate hedging strategy. Collateral managers of CBOs entered into agreements to pay fixed and receive floating on interest rate swaps. As interest rates fell during the period, CBO collateral managers were net payers on these swaps. Such an interest rate hedging strategy would not have been a problem if the CDO portfolios and liabilities were still intact. The collateral manager would have used fixed-rate payments from their portfolios to pay the fixed rate on the swap, and used the floating-rate payment coming from the swap to pay the floating-rate bondholders on their liabilities. But bond defaults on high-yield corporate bonds had reduced CBO portfolios and the working of overcollateralization triggers (discussed later) had accelerated the principal paydown of CBO liabilities. This caused the notional amount of the interest rate swap to be greater than the amount of the assets and liabilities in CBOs. As a result, many CBOs were overhedged, resulting in losses on their hedge positions.2

Despite the simplifying assumptions, the illustration above does demonstrate the basic economics of the CDO, the need for the use of an interest rate swap, and how the equity tranche realizes a return.

COMPLIANCE TESTS

The basic CDO structure is designed to split the aggregate credit risk of the collateral pool into various tranches, which are the overlying notes, each of which has a different credit exposure from the other. As a result each note exhibits a different risk/reward profile, and so will attract itself to different classes of investors.

The notes issued have different risk profiles as a result of their relative subordination, that is, the notes are structured in descending order of seniority. In addition, the structure makes use of credit enhancements to varying degrees, which may include:

- Overcollateralization: The overlying notes are lower in value compared to the underlying pool; for example, $250 million nominal of assets are used as backing for $170 million nominal of issued bonds.

- Cash reserve accounts: A reserve is maintained in a cash account and used to cover initial losses; the funds may be sourced from part of the debt proceeds.

- Excess spread: Cash inflows from assets exceed the interest service requirements of liabilities.

- Insurance wraps: Losses suffered by the asset pool are covered by insurance, for which an insurance premium is paid as long as the cover is needed.

The quality of the collateral pool is monitored regularly and reported on by the portfolio administrator, who produces the investor report. This report details the results of various compliance tests, which are undertaken at individual asset level as well as the aggregate level.

Compliance tests are specified as part of the process leading up to the issue of notes, in discussion between the originator and the rating agency or rating agencies. The ratings analysis is comprehensive and focuses on the quality of the collateral, individual asset default probabilities, the structure of the deal, and the track record and reputation of the originator. If a CDO fails an important compliance test such as the coverage tests described below, the portfolio administrator will inform the deal originator (or collateral manager). Upon this occurrence, an immediate restriction is placed on any further trading by the vehicle and the originator has 30 days to rectify the position. After this date, the only trading that is permitted is that required on a credit risk basis (to mitigate credit risk and possible further loss due to say, defaults in the portfolio). At the next coupon date, known as the determination date, if the collateral manager still fails the compliance test, then principal on the notes will begin to be paid off, in order of priority. During this phase, the CDO is also likely to be put on “credit watch” by the credit rating agency, with a view to possible downgrade, because the underlying portfolio will be viewed as having deteriorated in quality from the time of its original rating analysis.

There are two types of compliance tests, quality tests and coverage tests.

Quality Tests

Quality tests include a (1) minimum collateral diversification score, (2) minimum weighted-average rating, and (3) minimum weighted-average coupon, and weighted-average spread. These tests are calculated on a regular basis and also each time the composition of the assets changes—for example, because certain assets have been sold, new assets purchased, or because bonds have paid off ahead of their legal maturity date. If the test results fall below the required minimum, trading activity is restricted to only those trades that will improve the test results.

A collateral diversification score is used to gauge the diversity of the collateral's assets. All rating agencies have diversity scores. The greater the score value, the more diverse is the CDO portfolio across industries. Every time the composition of the collateral changes, a diversity measure is computed. The most well-known diversity score is the one developed by Moody's.

A measure is also needed to gauge the credit quality of the collateral. Certainly one can describe the distribution of the credit ratings of the collateral in terms of the percentage of the collateral's assets in each credit rating. However, such a measure would be awkward in establishing tests for a minimum credit rating for the collateral. There is a need to have one figure that summarizes the rating distribution test.

Moody's and Fitch have developed a measure to summarize the rating distribution. This is commonly called the weighted-average rating factor (WARF) for the collateral. This involves assigning a numerical value to each rating. These numerical values are called rating factors. The CDO manager must maintain a minimum average rating score. Unlike Moody's and Fitch, S&P uses a different system. S&P specifies required rating percentages that the collateral must maintain. Specifically, S&P requires strict percentage limits for lower-rated assets in the collateral portfolio.

Coverage Tests

The other type of compliance tests, coverage tests, are viewed as more important than quality tests, since if any of them are “failed,” the cash flows will be diverted from the normal waterfall as described earlier and will be used to begin paying off the senior notes until the test results improve. These include the overcollateralization test and the interest coverage test. We will be described each below.

Overcollateralization Tests

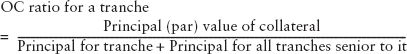

The overcollateralization ratio (OC ratio) for a tranche is found by computing the ratio of the principal balance of the collateral portfolio divided by the principal balance of that tranche plus all tranches senior to it. That is,

The higher the ratio, the greater protection there is for the note holders. Note that the OC ratio is based on the principal or par value of the assets. (Hence an overcollateralization test is also called a par value test.) An OC ratio is computed for specified tranches subject to the overcollateralization test. The overcollateralization test for a tranche involves comparing the tranche's OC ratio with the tranche's required minimum ratio as specified in the guidelines. The required minimum ratio is called the overcollateralization trigger. The overcollateralization test for a tranche is passed if the OC ratio is greater than or equal to its respective overcollateralization trigger.

For example, suppose that a cash flow CDO has two rated tranches that are subject to the overcollateralization test—classes A and B. Therefore, two overcollateralization ratios are computed for this deal. For each tranche, the overcollateralization test involves first computing the OC ratio as follows:

Once the OC ratio for a tranche is computed, it is then compared with the overcollateralization trigger for the tranche as specified in the guidelines. If the computed OC ratio is greater than or equal to the overcollateralization trigger for the tranche, then the test is passed with respect to that tranche.

Suppose that the overcollateralization trigger is 113% for class A and 101% for class B. Note that the lower is the seniority, the lower is the overcollateralization trigger. The class A overcollateralization test is failed if the ratio falls below 113%, and the class B overcollateralization test is failed if the ratio falls below 101%.

Interest Coverage Tests

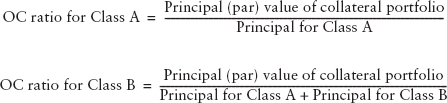

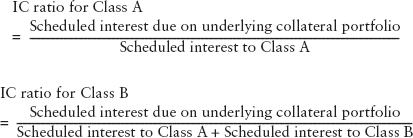

The interest coverage ratio (IC ratio) for a tranche is the ratio of scheduled interest due on the underlying collateral portfolio to scheduled interest to be paid to that tranche and all tranches senior to it. That is,

The higher the IC ratio, the greater is the protection. An IC ratio is computed for specified tranches subject to the interest coverage test. The interest coverage test for a tranche involves comparing the tranche's IC ratio with the tranche's interest coverage trigger (i.e., the required minimum ratio as specified in the guidelines). The interest coverage test for a tranche is passed if the computed IC ratio is greater than or equal to its respective interest coverage trigger.

Consider once again our hypothetical cash flow CDO where classes A and B are subject to the interest coverage test. The following two IC ratios therefore are computed:

1 Except that in a typical ABS deal such as a consumer or trade receivables deal, or a residential MBS deal, there are a large number of individual underlying assets, whereas with a CBO or CLO there may be as few as 20 underlying loans or bonds.

2 Douglas Lucas, Laurie S. Goodman, and Frank J. Fabozzi, Collateralized Debt Obligations: Structures and Analysis (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2006).