CHAPTER 8

Securitized and Synthetic Funding Structures

The accessibility of securitization techniques, together with greater liquidity in the credit derivative market, has given rise to new types of money market funding structures. These vehicles have enabled a wider range of market participants to tap the markets, often with illiquid or untradeable assets being used as synthetic collateral. They also provide a diversified funding source for banks, other financial institutions, and corporations. In this chapter we discuss funding vehicles that are structured as synthetic securitizations in the commercial paper and medium-term note markets. We also discuss a basic funding instrument, the basket total return swap, which is traded under an International Swap and Derivatives Association (ISDA) agreement and termed a credit derivative, but in practice works exactly as a repurchase agreement. We begin with a discussion of commercial paper and asset-backed commercial paper program.

COMMERICAL PAPER

Companies' short-term capital and working capital requirements are usually sourced directly from banks in the form of bank loans. An alternative short-term funding instrument is commercial paper (CP), which is available to corporations that have sufficiently strong credit ratings. CP is a short-term unsecured promissory note. The issuer of the note promises to pay its holder a specified amount on a specified maturity date. CP normally has a zero coupon and therefore trades at a discount to its face value. The discount represents interest to the investor in the period to maturity.

Originally, the CP market was restricted to borrowers with high credit ratings, and although lower-rated borrowers do now issue CP, sometimes by obtaining credit enhancements or setting up collateral arrangements, issuance in the market is still dominated by highly-rated companies. The majority of issues are very short-term, from 30 to 90 days in maturity; it is extremely rare to observe paper with a maturity of more than 270 days or nine months. This is because of regulatory requirements in the United States, which state that debt instruments with a maturity of less than 270 days need not be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Corporations therefore issue CP with a maturity less than nine months and thereby avoid the costs associated with registering issues with the SEC.

There are two major markets, the U.S. dollar market and the Eurocommercial paper market. CP markets are wholesale markets and transactions are typically very large in size. Although there is a secondary market in CP, very little trading activity takes place since investors generally hold CP until maturity.

The issuers of CP are often divided into two categories of companies, banking and financial institutions and non-financial companies. The majority of CP issues are by financial companies. Financial companies include not only banks but the financing arms of corporations such as General Motors Acceptance Corporation, Ford Motor Credit Co., and Daimler-Chrysler Financial. As noted above, most of the issuers have strong credit ratings, but lower-rated borrowers have tapped the market, often after arranging credit support from higher-rated companies such as letters of credit from banks, or by arranging collateral for the issue in the form of high-quality assets such as Treasury bonds. CP issued with credit support is known as credit-supported commercial paper, while paper backed with assets is known naturally enough, as asset-backed commercial paper. Paper that is backed by a bank letter of credit is termed LOC paper. Although banks charge a fee for issuing letters of credit, borrowers are often happy to pay it, since by so doing they are able to tap the CP market. The yield paid on an issue of CP is lower than on a commercial bank loan.

Although CP is a short-dated security, it is issued within a longer term program—usually for three to five years for Eurocommercial paper; U.S. CP programs are often open ended. For example a company might arrange a five-year CP program with a limit of $100 million. Once the program is established the company can issue CP up to this amount, say for maturities of 30 or 60 days. The program is continuous and new CP can be issued at any time—daily if required. The total amount in issue cannot exceed the limit set for the program. A CP program can be used by a company to manage its short-term liquidity—that is, its working capital requirements. New paper can be issued whenever a need for cash arises, and for an appropriate maturity.

Issuers often roll over their funding and use funds from a new issue of CP to redeem a maturing issue. There is a risk that an issuer might be unable to roll over the paper where there is a lack of investor interest in the new issue. To provide protection against this risk an issuer often arranges a standby line of credit from a bank, normally for all of the CP program, to draw against in the event that it cannot place a new issue. Bank lines of credit are generally reviewed on a yearly basis. Unlike revolving credit facilities, they are not legally binding commitments and can be withdrawn if a borrower's creditworthiness deteriorates.

There are two methods by which CP is issued, known as direct-issued or direct paper and dealer-issued or dealer paper. Direct paper is sold by the issuing firm directly to investors, and no agent bank or securities house is involved. It is common for financial companies to issue CP directly to their customers, often because they have continuous programs and constantly rollover their paper. It is therefore cost-effective for them to have their own sales arm and sell their CP direct. The treasury arms of certain nonfinancial companies also issue direct paper. Dealer paper is sold using a banking or securities house intermediary. Some large companies issue CP both directly and through dealers.

We refer to CP programs as described above as conventional CP programs to distinguish them from the next type of CP programs we discuss, asset-backed commercial paper.

ASSET-BACKED COMMERCIAL PAPER

The rise in securitization has led to the growth of short-term instruments backed by the cash flows from other assets, known as asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP). As explained in Chapter 4, securitization is the practice of using the cash flows from a specified asset, such as residential mortgages, car loans, or commercial bank loans, as backing for an issue of bonds. The assets themselves are transferred from the original owner (the originator) to a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that is a specially created legal entity created to make them separate and bankruptcy-remote from the originator. In the meantime, the originator is able to benefit from capital market financing, often charged at a lower rate of interest than that paid by the originator on its own debt.

Generally, securitization is used as a funding instrument by companies for three main reasons: (1) it offers lower-cost funding compared with than traditional bank loan or bond financing; (2) it is a mechanism by which assets such as corporate loans or mortgages can be removed from the balance sheet, thus improving the lender's return on assets or return-on-equity ratios; and (3) it increases a borrower's funding options. When entering into a securitization, an entity may issue term securities against assets into the public or private market, or it may issue commercial paper via a special vehicle known as a conduit. These conduits are usually sponsored by commercial banks.

Corporations access the commercial paper market for normal short-term funding requirements and also as an interim step toward permanent financing, rolling over individual issues as part of a longer-term program and using interest-rate swaps to arrange a fixed-rate if required. Conventional CP issues discussed in the previous section are a form of direct borrowing based on the borrower's balance sheet and creditworthiness. By borrowing directly from the investor and eliminating the bank as an intermediary (except possibly as selling agent), a corporation can fund at a cheaper rate than by borrowing from a commercial bank. CP is a well-known example of disintermediation that has significantly reduced the role of commercial banks in financing large corporations and led commercial banks to move in the direction of investment banking to serve their large corporate customers. (In the case of the United States, after a long but ultimately successful battle to remove the legislative barriers that had separated commercial banking and investment banking since the depression in the 1930s.) Issuing ABCP enables an originator to benefit from money market financing to which it might otherwise not have access because its credit rating is not sufficiently strong. A bank may also issue ABCP for balance sheet or funding reasons. ABCP trades, however, exactly as conventional CP. However, the administration and legal treatment is more onerous because of the need to establish the CP trust structure and issuing SPV. The servicing of an ABCP program follows that of conventional CP and is carried out by the same entities, such as the “trust” arms of banks such JPMorgan Chase, Deutsche Bank, and Bank of New York.

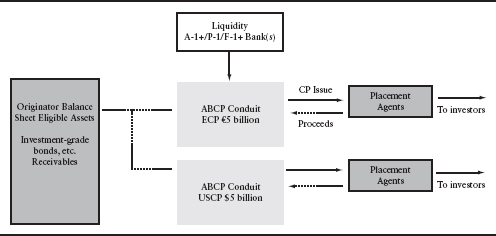

Exhibit 8.1 details a hypothetical ABCP issue and typical structure.

Basic Characteristics

ABCP programs are invariably issued via SPVs, which in the money markets are known as conduits. They are typically established by commercial banks and finance companies to enable them to access LIBOR-based funding, at close to LIBOR, and to obtain regulatory capital relief. This can be done for the bank or a corporate customer.

An ABCP conduit has the following features:

EXHIBIT 8.1 Hypothetical ABCP Issue and Typical Structure

- It is a bankruptcy-remote legal entity that issues CP to finance the purchase of assets from a seller of assets.

- The interest on the CP issued by the conduit, and its principal on maturity, will be paid out of the receipts on the assets purchased by the conduit.

- Conduits have also been set up to exploit credit arbitrage opportunities, such as raising finance at LIBOR to invest in high-quality assets such as investment-grade rated structured finance securities that pay above LIBOR.

The assets that can be funded via a conduit program are many and varied. To date they have included:

- trade receivables and equipment lease receivables;

- credit card receivables;

- auto loans and leases;

- corporate loans, franchise loans, mortgage loans;

- real estate leases;

- investment-grade rated structured finance bonds such as ABS, MBS and CDO notes; and

- future (expected) cash flows.

Conduits are classified into “program types,” which refer to the make-up of the underlying asset portfolio. They can be single-seller or multiseller, which indicates how many institutions or entities are selling assets to the conduit. They are also designated as funding or securities credit arbitrage vehicles. A special class of conduit known as a structured investment vehicle (SIV, sometimes called a special investment vehicle) exist that issue both CP and medium-term notes (MTNs), and which are usually credit arbitrage vehicles.

Credit Enhancement and Liquidity Support

To make the issue of liabilities from a conduit more appealing to investors or to secure a particular credit rating, a program sponsor usually arranges some form of credit enhancement and/or backup borrowing facility. (We discussed credit enhancement mechanisms in structuring a securitization in Chapter 5.) Two types of credit enhancement are generally used in ABCP: either pool-specific or program-wide. Pool-specific credit enhancement covers only losses on a specific named part of the asset pool and cannot be used to cover losses in any other part of the asset pool. Program-wide credit enhancement is a fungible layer of credit protection that can be drawn on to cover losses from the start or if any pool-specific facility has been used up.

Pool-specific credit enhancement instruments include the following:

- over-collateralization, where the nominal value of the underlying assets exceeds that of the issued paper;

- surety bond: a guarantee of repayment from a sponsor or other bank;

- letter of credit: a standby facility from which the issuer can draw funds;

- irrevocable loan facility; and

- excess cash invested in eligible instruments such as U.S. Treasury bills.

The size of a pool-specific credit enhancement facility is quoted as a fixed percentage of the asset pool.

Program-wide credit enhancement is in the same form as pool-specific enhancement, and acts as a second layer of credit protection. It may be provided by a third party such as a commercial bank as well as by the sponsor.

Liquidity support is separate from credit enhancement. While credit enhancement facilities cover losses due to asset default, liquidity providers undertake to make available funds should they be required for reasons other than asset default. A liquidity line is drawn on, if required, to ensure timely repayment of maturing CP. This might occur because of market disruption (such that the issuer could not place new CP), an inability of the issuer to roll maturing CP, or because of asset and liability mismatches. This last item is the least serious situation, and reflects that in many cases long-dated assets are used to back short-dated liabilities, and cash flow dates often do not match. The availability of a liquidity arrangement provides comfort to investors that CP will be repaid in full and on time, and is usually arranged with a commercial bank. It is usually provided as a loan agreement for an amount equal to 100% of the face amount of CP issued, under which the liquidity provider agrees to lend funds to the conduit as required. The security for the liquidity line comes from the underlying assets.

Exhibit 8.1 illustrates a typical ABC structure issuing to the U.S. CP and Euro CP markets. Exhibit 8.2 shows a multiseller conduit set up to issue in the ECP market.

Illustration of an ABCP Structure

In Exhibit 8.3 we illustrate an hypothetical example of a securitization of bank loans in an ABCP structure. The loans, denominated in sterling, have been made by ABC Bank and are secured on borrowers' specified assets, for example liens on property, cash flows of the borrowers' businesses, or other assets. The bank makes a “true sale” of the loans to a SPV, named Claremont Finance. This has the effect of removing the loans from the bank's balance sheet, reducing the bank's regulatory capital requirements, and also protecting those loans in the event of bankruptcy or liquidation of the bank. The SPV raises finance by issuing commercial paper, via its appointed CP dealer(s), which is the treasury desk of MC Investment Bank. The paper is rated A-1/P-1 by the rating agencies and is issued in U.S. dollars. The liability of the CP is met by the cash flow from the original ABC Bank loans.

ABC manager is the SPV manager for Claremont Finance, a subsidiary of ABC Bank. Liquidity for Claremont Finance is provided by ABC Bank, which also acts as the hedge provider. Hedging, to the extent required, is effected by means of an interest rate swap agreement, and in cases where some of the loans are foreign-currency denominated, a currency swap agreement between Claremont Finance and ABC Bank. Depending on its own interest rate and currency positions and risk management strategies, ABC Bank may further hedge its positions in all or parts of those swaps. The trustee for the transaction is Trust Bank Limited, which acts as security trustee and represent the investors in the event of default. The other terms of the structure are shown in Exhibit 8.4.

EXHIBIT 8.2 Multiseller EABCP Conduit

EXHIBIT 8.3 Claremont Finance ABCP Structure

SYNTHETIC FUNDING STRUCTURES

In this section, we discuss recent developments in credit-derivative-based synthetic structures, which are now being used for liquidity and balance sheet asset-liability management. These combine total return swaps (discussed in Chapter 3) with commercial paper and medium-term note issuance vehicles, and enable originators to raise LIBOR-based funding from wholesale interbank markets. To begin, we consider the simplest arrangement, the funded basket total return swap.

EXHIBIT 8.4 Terms of the Hypothetical Claremont Finance ABCP Structure

The Basket Total Return Swap

The total return swap (TRS) may be used as a funding tool to secure off-balance-sheet financing for assets held (for example) on a market making book. It is most commonly used in this capacity by broker-dealers and securities houses that have little or no access to unsecured or LIBOR-flat funding. When used for this purpose, the TRS is similar to a repurchase agreement (repo) transaction, although there are detail differences. (A repo is an agreement to sell a security for a specified price and buy it back later at another specified price. It is essentially a secured loan. The party that sells the securities and agrees to buy them bank is the party that needs financing; the party that buys the securities and agrees to sell them bank is the party that provides the financing.) Often a TRS approach is used instead of a classic repo when the assets that require funding are less liquid or not really tradable. These assets can include lower-rated bonds, illiquid bonds (such as certain asset-backed securities (ABS), mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and assets such as hedge fund interests.

Bonds that are taken on by the TRS provider must be acceptable to it in terms of credit quality. If no independent price source is available, the TRS provider may insist on pricing the assets itself.

As a funding tool the TRS is transacted as follows:

- The broker-dealer swaps out a bond or basket of bonds that it owns to the TRS counterparty (usually a bank), who pays the market price for the security or securities.

- The maturity of the TRS can be for anything from one week to one year or even longer. For longer-dated contracts, a weekly or monthly reset is usually employed, so that the TRS is repriced and cash flows exchanged each week or month.

- The funds that are passed over by the TRS counterparty to the broker-dealer have the economic effect of being a loan to cover the financing of the underlying bonds. This loan is charged at LIBOR plus a spread.

- At the maturity of the TRS, the broker-dealer owes interest on funds to the swap counterparty, while the swap counterparty owes the market performance of the bonds to the broker-dealer if they have increased in price. The two cash flows are netted out.

- For a longer-dated TRS that is reset at weekly or monthly intervals, the broker-dealer owes the loan interest plus any decrease in basket value to the swap counterparty at the reset date. The swap counterparty will owe any increase in value.

By entering into this transaction the broker-dealer obtains LIBOR-based funding for a pool of assets it already owns, while the swap counterparty earns LIBOR plus a spread on funds are effectively secured by a pool of assets. This transaction takes the original assets off the balance sheet of the broker-dealer during the term of the trade, which might also be desirable.

The broker-dealer can add or remove bonds from or to the basket at each reset date. When this happens, the swap counterparty revalues the basket and provides more funds or receives funds as required. Bonds are removed from the basket if they have been sold by the broker-dealer, while new acquisitions can be funded by being placed in the TRS basket.

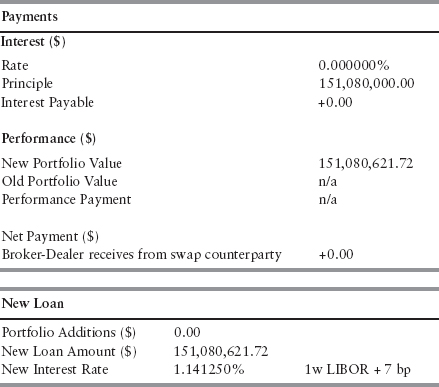

We illustrate a funding TRS trade using an example. Exhibit 8.5 shows a portfolio of five hypothetical convertible bonds on the balance sheet of a broker-dealer. The exhibit also shows market prices. This portfolio has been swapped out to a TRS provider in a six-month, weekly reset TRS contract. The TRS bank has paid over the combined market value of the portfolio at a lending rate of 1.14125%. This represents one-week LIBOR plus 7 bp. We assume the broker-dealer usually funds at above this level, and that this rate is an improvement on its normal funding. It is not unusual for this type of trade to be undertaken even if the funding rate is not an improvement, however, for diversification reasons.

We see from Exhibit 8.5 that the portfolio has a current market value of approximately $151,080,000. This value is lent to the broker-dealer in return for the bonds.

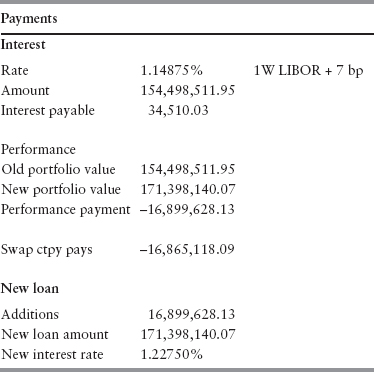

One week later the TRS is reset. We see from Exhibit 8.6 that the portfolio has increased in market value since the last reset. Therefore, the swap counterparty pays this difference over to the broker-dealer. This payment is netted out with the interest payment due from the broker-dealer to the swap counterparty. The interest payment is shown as $33,526.

Exhibit 8.7 shows the basket after the addition of a new bonds, and the resulting change in portfolio value.

Synthetic ABCP Conduit

The latest development in ABCP conduits is the synthetic structure. As with synthetic structured credit products, this structure uses credit derivatives to effect an economic transfer of risk and exposure between the originator and the issuer, so that there is not necessarily a sale of assets from the originator to the issuer. We will describe synthetic conduits by means of an hypothetical transaction, which is a total return, swap-backed ABCP structure.

Exhibit 8.8 is a structure diagram for a synthetic ABCP vehicle that uses total return swaps in its structure. It illustrates a hypothetical conduit, Golden Claw Funding, which issues paper into both the U.S. CP market and the Euro CP market. It has been set up as a funding vehicle, with the originator accessing the CP market to fund assets that it holds on its balance sheet. The originator can be a bank, non-bank financial institution such as a hedge fund, or a corporation. In our case study the originator is a hedge fund called ABC Fund Limited.

The structure shown in Exhibit 8.8 has the following features:

- The CP issuance vehicle and the Purchase Company (PC) are based offshore at a location such as Jersey, Ireland, or Cayman Islands.

EXHIBIT 8.6 Spreadsheet Showing Basket of Bonds at TRS Reset Date Plus Performance and Interest Payments Due from Each TRS Counterparty

EXHIBIT 8.7 TRS Basket Value After Addition of New Bond

- The conduit issues CP in the U.S. dollar market via a co-issuer based in Delaware. It also issues Euro-CP via an offshore SPV.

- Proceeds of the CP issue are loaned to the PC, which uses these funds to purchase assets from the originator. As well as purchasing assets directly, the vehicle may also acquire an “interest” in assets that are held by ABC Fund Limited via a note referenced to a basket of assets. If assets are purchased and put directly onto the balance sheet of the PC, this is akin to what happens in a conventional ABCP structure. If interests in the assets are acquired via referenced note, then they are not actually sold to the PC, and remain on the balance sheet of ABC Fund Limited. Assets can be bonds, structured finance bonds, equities, mutual funds, hedge fund shares, convertible bonds, synthetic products, and private equity.

- Simultaneously, as it purchases assets or a note linked to assets, the PC enters into a TRS contract with ABC Fund Limited under which it pays the performance on the assets and receives interest on the CP proceeds it has used to purchase assets and referenced notes. The TRS is the means by which ABC Fund retains the economic interest in the assets it is funding, and the means by which the PC receives the interest it needs to pay back to Golden Claw as CP matures.

EXHIBIT 8.8 Synthetic ABCP Conduit, Hypothetical Deal “Golden Claw Funding”

- The issue vehicle itself may also purchase assets and referenced notes, so we show in Exhibit 8.8 that it also has a TRS between itself and ABC Fund Limited.

The Golden Claw structure is a means by which funds can be raised without a true sale structure. The TRS is guaranteed by the sponsor bank, which will ensure that the conduit is rated at the short-term rating of that sponsor bank. As CP matures, it will be repaid with a rollover issue of CP, with interest received via the TRS contract. If CP cannot rolled over, then the PC or the issuer will need to sell assets or referenced notes to repay principal, or otherwise the TRS guarantor will need to cover the repayment.

Essentially, the TRS is the means by which the conduit can be used to secure LIBOR-flat based funding for the originator, as long as payments under it are guaranteed by a sponsor or guarantor bank. Alternatively, the originator can arrange for a banking institution to provide a standby liquidity backup for the TRS in the event that it cannot roll over maturing CP. This service would be provided for a fee.

To show how the conduit cash flow mechanics would work, consider this example. Assume the first issue of CP by the Golden Claw structure. The vehicle issues $100 nominal of one-month CP at an all-in price of $99.50. These funds are lent by the vehicle to its purchase company, which uses these funds to buy $99.50 worth of assets synthetically from ABC Fund in the form of par-priced options referenced to these assets. Simultaneously it enters into a TRS with ABC Fund for a nominal amount of $100.

On the maturity of the CP, assume that the reference assets are valued at $103. This represents an increase in value of $3. ABC Fund will pay this increase in value to the purchase company, which will then pay this, under the terms of the TRS, back to ABC Fund. (In practice, this cash flow nets to zero, so no money actually moves.) Also under the terms of the TRS, ABC Fund pays the maturing CP interest of $0.50, plus any expenses and costs of Golden Claw itself, to the purchase company, which in turn pays this to Golden Claw, enabling it to repay CP interest to investors. The actual nominal amount of the CP issue is repaid by rolling it over (reissuing it).

If for any reason CP cannot be rolled over on maturity, the full nominal value of the CP must be paid under the terms of the TRS by ABC Fund to the purchase company.

Offshore Synthetic Funding Structures

Investment banks are increasingly turning to offshore synthetic structured solutions for their funding, regulatory capital, and accounting treatment requirements. We saw earlier how total return swaps could be used to obtain off-balance-sheet funding of assets at close to LIBOR, and how synthetic conduit structures can be used to access the ABCP market at LIBOR or close to LIBOR. Below we discuss synthetic structures that issue in both the CP and the MTN market, and are set up to provide funding for investment bank portfolios or reference portfolios of their clients. There are a number of ways to structure these deals, some using multiple SPVs, and new variations are being introduced all the time.

We illustrate the approach taken when setting up these structures by describing two different hypothetical funding vehicles.

Offshore Synthetic Funding Vehicle

A commercial bank or an investment bank can set up an offshore SPV that issues both CP and MTNs to fund underlying assets that are acquired synthetically. We describe this with an illustration.

Assume an investment bank wishes to access the CP and MTN markets to borrow funds at close to LIBOR. It sets up an offshore SPV, Long-Term Funding Limited, which has the freedom to issue the following liabilities as required: CP, MTN, repo agreements, and guaranteed investment contracts (GICs). GICs are deposit contracts that pay either a fixed coupon to lenders or a fixed spread over LIBOR.

These liabilities are used to fund the purchase of assets that are held by the investment bank. These assets are purchased synthetically via TRS contracts or sometimes in cash form as a reverse repo trade. The vehicle is illustrated in Exhibit 8.9.

The vehicle is structured in such a way that the liabilities it issues are rated at A-1/F-1 and Aaa/AAA. It enables the originating bank to access the money and capital markets at rates that are lower than it would otherwise obtain in the interbank (unsecured) market. The originator invests its own capital in the structure in the form of an equity piece. At the same time, a liquidity facility is also put in place, to be used in the event that the vehicle is not able to pay maturing CP and MTNs. The liquidity facility is an additional factor that provides comfort to the rating agencies.

EXHIBIT 8.9 Long-Term Funding Limited: Offshore Synthetic Funding Vehicle

The vehicle's asset structure is composed of mainly synthetic securities, accessed using funded TRS contracts. However, to retain flexibility, the vehicle is also able to bring in assets in cash form in the form of reverse repo transactions. Possible types of assets that can be “acquired” by Long-Term Funding Ltd. include short-term money market instruments rated AAA, bullet corporate bonds rated from AAA to BB, structured finance securities (including ABS, RMBS, and CMBS securities rated from AAA to BB), government agency securities such as those issued by Ginnie Mae and Pfandbriefe securities, securities issued by government-sponsored entities (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac), and secondary-market bank loans and syndicated loans rated at AAA to BBB. Reference assets can be denominated in any currency, and currency swaps are arranged to hedge the currency mismatch that results from the vehicle issuing in U.S. dollars and euros. In addition to the quality of the underlying reference assets, the credit rating of the TRS and repo counterparties is also taken into consideration when the liabilities are rated.

As for the liability structure, Long-Term Funding Ltd. finances the purchase of TRS and reverse repos by issuing CP, MTNs, and GICs. The interest-rate risk that arises from issuing GICs is hedged using interest-rate swaps. The ability of Long-Term Funding Ltd. to issue different types of liabilities allows the originating bank to access funding at any maturity from one-month to very long-term, and across a variety of sources. For instance, CP may be bought by banks, corporations, money market funds, and supranational institutions such as the World Bank; GIC contracts are frequently purchased by insurance companies.

Multi-SPV Synthetic Conduit Funding Structure

One of the main drivers behind the growth of synthetic funding structures has been the need for banks to reduce regulatory capital charges. While banks have achieved this by setting up offshore SPVs that issue liabilities and references assets synthetically, recent proposals on changing accounting treatment for SPVs means that this approach may not be sufficient for some institutions. The structure we describe here can reference an entire existing SPV synthetically, in effect a synthetic transfer of assets that have already been synthetically transferred. The vehicle would be used by banks or fund managers to obtain funding and capital relief for an entire existing portfolio without having to move any of the assets themselves.

EXHIBIT 8.10 Multi-SPV Offshore Synthetic Conduit Funding Structure

The key to the synthetic multi-SPV conduit is the CP and MTN issuance vehicle, which is a standalone vehicle established by a commercial or investment bank. Such a vehicle provides funding to an existing SPV or SPVs, and acquires the assets synthetically. The assets are deemed as being held within the structure and as such attract a 0% risk-weighting under Basel I.

The structure is illustrated in Exhibit 8.10. This structure has the following features:

- An offshore SPV issues CP into the U.S. and Euro markets.

- The offshore conduit, Funding Corporation Ltd., purchases the entire balance sheet of an existing SPV synthetically. The funds issued in the CP market are used to provide a funded TRS contract to the SPV whose assets are being funded.

- The customer gains a funding source and also retains the return on the assets; however it benefits from a reduced capital charge and no longer needs to mark the assets to market.

- The investment bank, originator, and CP investors (in that order) offer to bear any losses on the reference portfolio due to credit events or default, and earn a fee income for setting up this facility.

- Assets and additional SPVs can be added at any time.

- A liquidity facility is in place in the event that CP cannot be issued.

This structure is yet another example of the flexibility and popularity of credit derivatives, and structured credit products created from credit derivatives, in the debt capital markets today.

Combined Referenced Note and TRS Funding Structure

For a number of reasons, entities such as hedge funds or other investment companies, whether they are independent companies or parts of banking or bancassurance conglomerates, are not able to obtain funding from mainstream banks directly. Hedge funds, for example, are commonly funded via prime brokerage facilities set up with banks. Put simply, under a prime brokerage, the provider of the facility holds the assets of the hedge fund in custody, and these assets act as security collateral against which funds are advanced. (A prime broker acts in a similar capacity for a hedge fund in its foreign-exchange trading operations, confirming and settling trades with counterparties on behalf of the hedge fund and in effect substituting the credit of the prime broker for that of the hedge fund. Prime brokers also provide securities clearance and custody services to hedge funds.) These funds are used by the hedge funds to pay for the assets they have purchased and are then lent by the primer broker at a spread over LIBOR, typically 50 to 70 bp. The prime broker also lends assets to cover short positions.

Many investment companies hold positions in illiquid assets, such as hedge fund-of-funds shares, or other difficult-to-trade assets. It is more difficult to raise funds in the wholesale markets using such assets as collateral because of the problem associated with transferring them to the custody of the cash lender. The advent of credit derivatives and financial engineering has enabled companies to get around this problem by setting up tailor-made structures for funding purposes. Here we describe an example of a funding or liquidity structure that raises cash in the wholesale market via a note and TRS structure that references a basket of illiquid assets.

Assume two entities that are part of a bancassurance group: a regulated broker-dealer (“Smith Securities”) and a hedge fund derivative investment house (“Smith Investments Company”). The investment house raises funds primarily from its parent banking group; however for diversity purposes, it also wishes to raise funds from other sources. One such source is the wholesale markets via a note and TRS structure as illustrated in Exhibit 8.11.

The lender is an investment bank (“ABC Bank”) that is willing to advance funds to the investment company, secured by its assets, at a rate of LIBOR plus 20 bp. This is a considerable saving on the investment company's cost of funds with a prime broker, and comparable with its parent group funding rate. However its assets cannot be transferred as they are untradeable assets, and so they cannot act as collateral in the normal way one observes in, for example, repo trades.

Instead we can create the following structure that will enable the funding to be raised:

EXHIBIT 8.11 Combined Note and TRS Funding Structure

- ABC Bank plc does not lend funds directly; instead it purchases a two-year note at a price of par. The return on this note is linked to the performance of a basket of assets held by Smith Investment Company. Because Smith Investment Company is an unregulated entity, it cannot issue a note into the wholesale markets. Consequently, the note is issued by its sister company, Smith Securities.

- The funds raised by the sale of the note are transferred, in the form of a loan, from Smith Securities to Smith Investment Company at LIBOR-flat.

- Simultaneously the two companies enter into a TRS arrangement wherein the start and maturity dates matching that of the note. Under this TRS, Smith Securities receives the performance of the basket of assets and pays LIBOR-flat.

- Also simultaneously, Smith Investment Company and ABC Bank plc enter into a TRS arrangement whereby the bank pays the performance of the basket of assets and receives LIBOR plus 20 bp.

The net cash flow of this structure is such that Smith Investment Company pays ABC Bank plc LIBOR plus 20 bp, and raises funds via the proceeds of the note issue by Smith Securities. The economic effect is that of a two-year loan from ABC Bank to Smith Investment Company, but because of legal, regulatory, operational, and administrative restrictions we need to have the structure described above to effect this.

Note that under some jurisdictions, it is not possible for group companies to make inter-company loans, particularly if the two companies are incorporated in different countries, without attracting withholding tax on the loans. For example, the maximum permissible maturity for inter-company loans may be one year. To get around this, in Exhibit 8.11. we have shown the loan from Smith Securities to be a 1-year loan, which is then rolled over for another year on maturity.