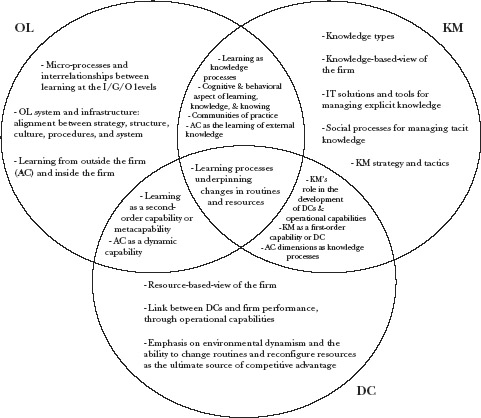

Figure 8.2 summarizes our conclusions about the domains and boundaries of the OL, KM, DC, and AC fields. We see these boundaries as fluid. They will evolve as the dialogue between members of these fields continues.

Figure 8.2 Boundaries of the Organizational Learning (OL), Knowledge Management (KM), Dynamic Capabilities (DC), and Absorptive Capacity (AC) Fields

In Figure 8.2, we show OL, KM, and DC as overlapping fields of research, but we recognize that there are topics that are dealt with primarily in one of the fields, and topics in which one field is more advanced in its development than the others. For example, we see OL as the most advanced in terms of providing a multilevel theory of learning in organizations. We also note that OL advances the view of an OL system or infrastructure where organizational level storehouses of knowledge—strategy, structure, systems, culture, and procedures—are aligned. In contrast, we see the KM field focused on creating a knowledge-based view of the firm, where the creation and integration of knowledge is the reason why firms exist. Similarly, the dynamic capabilities perspective is unique in providing a dynamic perspective of the resource-based view of the firm and in suggesting the ability to change routines and reconfigure resources (including knowledge routines and knowledge resources) as the ultimate source of competitive advantage.

The boundary between OL and KM

From a positivist perspective, one basic difference between OL and KM is that where one of KM’s main focuses is understanding the nature of knowledge as an asset or a stock, OL primarily emphasizes the processes through which knowledge changes or flows. That is, there is a distinction between studying what is learned and studying the process of learning, or between studying content and process. Schendel (1996), for example, emphasizes the need to understand learning as a process, when he states that ‘the capacity to develop organizational capability may be more important in creating competitive advantage than the specific knowledge gained’ (1996: 6). KM views knowledge as a firm resource that can lead to sustainable competitive advantage. Thus, we position the knowledge-based view of the firm in Figure 8.2 within the boundaries of the OK domain. Discussion is focused on trying to understand what knowledge is, on defining knowledge typologies, and contrasting explicit and tacit knowledge and the technical and social mechanisms to support them. We conclude that OK has a more content view of knowledge, while OL is primarily interested in the underlying processes.

There is a growing agreement in the OL literature that for learning to occur, changes in cognition and/or behavior must take place. Whereas the KM literature has a strong cognitive side, it also addresses knowledge and knowing as grounded in action and as processes that require both cognitive and behavioral activity. Furthermore, constructivist approaches to knowledge emphasize that knowledge is constructed in interaction with the world, that knowledge is situated in practice, and that knowledge is relational, mediated by artifacts, contextualized, and dynamic (Blackler, 1995). We conclude that although the OL field has been the most explicit in explaining the cognitive and behavioral aspects of the learning phenomenon, KM has extended its focus on cognition, to incorporate the action orientation.

As suggested earlier in this chapter, OL and KM also overlap, because learning has been increasingly defined in terms of knowledge processes. For example, Argote (1999) defines learning as ‘knowledge acquisition’ and states that learning involves the processes through which members share, generate, evaluate, and combine knowledge. On the knowledge management side, process views take the form of ‘life cycle’ models. King, Chung, and Haney (2008) offer the most comprehensive of them consisting of several parallel paths, starting from creation (or acquisition), refinement, storage, then transfer (or sharing), and ending with utilization leading to organizational performance. In addition, as mentioned in the previous point, knowledge is not viewed as purely cognitive any more. Thus, when the notion of static knowledge is replaced by dynamic knowing and the agenda switches from managing knowledge assets to studying the knowledge-associated processes, such as creation, retention, and transfer, there is a powerful opportunity to unify the insights from both the organizational learning and organizational knowledge communities.

When studied from a social constructivist perspective, OL and KM share the recognition that learning and knowing are situated in practice. This research includes the study of communities of practice (Brown and Duguid, 1991) and activity systems (Blackler, 1995; Spender, 1996). The fundamental idea is that it is impossible to separate learning from working (Brown and Duguid, 1991) and that knowledge exists in socially-distributed activity systems, where participants employ their situated knowledge in a context which is itself constantly developing (Gherardi, Nicolini, and Odella, 1998).

In terms of the levels of analysis, several authors in the OL and KM fields (e.g. Crossan et al., 1999; Kogut and Zander, 1992; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) have proposed that learning occurs and that knowledge exists at the individual, group, organizational, and inter-organizational or network levels. This fourth level of analysis has attracted a great deal of attention from researchers interested in the role of learning in alliances, joint ventures, strategic groups, and inter-firm relationships in general (e.g. Doz, 1996; Inkpen and Crossan, 1995; Lyles and Salk, 1996). An early debate, particularly in the OL field, questioned the existence of organizational-level learning. According to Argote (1999), a ‘litmus test’ for determining whether organizational learning has occurred is analyzing whether organizational knowledge persists in the face of individual turnover. Furthermore, work by Nelson and Winter (1982) describes knowledge at the organizational level and refers to organizational routines as the organization’s genetic material, some explicit in bureaucratic rules, some implicit in the organization’s culture. As the field has evolved, OL and KM researchers seem to agree that organizations are more than the sum of individuals and that by acknowledging the existence of non-human repositories of knowledge and organizational learning systems (Shrivastava and Grant, 1985), the capacity to learn, to know, and to have a memory (Walsh and Rivera, 1991) can be attributed to firms.

Once the different levels of analysis are recognized, the next step is to provide a theory that links the levels, explaining the micro-processes by which learning and knowledge at one level become learning and knowledge at another level. Schwandt’s (1995) Dynamic Organizational Learning Model, for example, moves in this direction. In this model, organizational learning is a dynamic social system defined as ‘a system of actions, actors, symbols, and processes that enables an organization to transform information into valued knowledge, which, in turn, increases its long-run adaptive capacity’ (Schwandt, 1995: 370). Four learning subsystems (environmental interface, action-reflection, dissemination and diffusion, and meaning and memory) and their associated processes explain how individuals and groups in organizations collectively engage in social actions of learning. Work from Crossan et al. (1999), Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), and Spender (1994, 1996) are other examples of ambitious efforts towards multilevel research. From our analysis of this work, we argue that OL is more advanced than KM in terms of providing this multilevel theory of how learning occurs at the individual, group, and organizational levels, how learning at one level impacts learning at other levels, and how knowledge flows from one level to the others. When discussing multiple levels of knowledge, the KM agenda has centered on tacit versus explicit knowledge and person to person transfer. For example, Spender (1994, 1996) has integrated the tacit and explicit taxonomy with the individual and social levels of analysis to present a matrix of four types of organizational knowledge: conscious, automatic or non-conscious, objectified or scientific, and collective. He discusses the ‘action-domains’ of each of the four types of knowledge and describes learning as the conversion from one type of knowledge to another. Still, the cognitive and behavioral processes involved in these learning flows need to be identified in order to provide useful prescriptions to firms.

To develop a multilevel theory of knowledge in organizations, KM also needs to establish relationships between the different knowledge-associated processes at different levels. For example what for one individual is knowledge sharing may be knowledge acquisition (learning) for a group or what for one individual is knowledge creation (learning) may be knowledge access for a group. In addition, when, for example, the knowledge transfer process is discussed at the group level, what is viewed as a transfer of current knowledge in the eyes of the sender may be seen as the acquisition of new knowledge by the receiver. These examples show that OL and OK involve many knowledge and learning processes and that there are significant opportunities for the two fields to work together to build a theory that relates the processes at different levels of analysis.

Finally, we propose in Figure 8.2 that the OL literature has most explicitly discussed the development of a learning system or infrastructure, which consists of embedded learning in the strategy, structure, culture, systems, and procedures of the firm. This learning infrastructure affects and is affected by learning processes and the different elements of the systems need to be aligned with each other for the firm to be successful.

The boundaries of OL and KM with DC

At its core, the dynamic capabilities perspective studies how change in routines and resources leads to competitive advantage. Because dynamic capabilities involve change, they involve learning—change in cognition and change in behavior, and because dynamic capabilities work on routines and resources, they involve knowledge—the most valuable, rare, and hard-to-imitate firm resource. Winter’s (2003) hierarchy of capabilities was instrumental in making these connections explicit: operational capabilities represent how things are currently done (current knowledge), dynamic capabilities change operational capabilities, and learning is the ultimate capability that guides the development, evolution, and use of dynamic and operational capabilities (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000).

In one of the most comprehensive efforts to link knowledge and dynamic capabilities explicitly, Zollo and Winter (2002) propose a ‘knowledge evolution cycle’ to describe the development of dynamic capabilities and operational routines; this cycle enables firms to change the way they do things in pursuit of greater rents. The knowledge evolution cycle includes four phases: generative variation, internal selection, replication, and retention. In the variation phase, individuals and groups generate ideas on how to approach old problems in novel ways or how to tackle new challenges. The selection phase implies the evaluation of ideas for their potential for enhancing the firm’s effectiveness. Through knowledge articulation, analysis, and debate, ideas become explicit and the best are selected. The replication phase involves the codification of the selected change initiatives and their diffusion to relevant parties in the firm. The application of the changes in diverse contexts generates new information about the routines’ performance and can initiate a new variation cycle. In the retention phase, changes turn into routines and knowledge becomes increasingly embedded in human behavior. There is stark similarity in these learning processes to those that have been well developed in the OL and KM literatures.

Building on this work, Cepeda and Vera (2007) delineated the connections between KM and DC when they stated that: (1) capabilities are organizational processes and routines rooted in knowledge; (2) the input of dynamic capabilities is an initial configuration of resources and operational routines; (3) dynamic capabilities involve a transformation process of the firm’s knowledge resources and routines; and (4) the output of dynamic capabilities is a new configuration of resources and operational routines.

Finally, Easterby-Smith and Prieto (2008) have offered an integrative framework of the learning, knowledge, and capabilities concepts. They argue that because learning capabilities act as the source of dynamic capabilities (Zollo and Winter, 2002) and learning can be defined in terms of the processes of knowledge creation, transfer, and retention, the distinctions between knowledge management and dynamic capabilities are more of terminology than of essence. Easterby-Smith and Prieto (2008) proposed a complex link to performance that can be summarized by the following points: (1) dynamic capabilities and knowledge management are first-order capabilities that modify existing resources and operational routines over time; (2) learning is a second-order capability that contributes to the evolution of both dynamic capabilities and knowledge management; (3) dynamic capabilities themselves do not lead to competitive advantage, but competitive advantage depends on the new configurations of resources and operational routines resulting from them; and, finally, (4) dynamic capabilities enabled by knowledge management are antecedents of specific operational/functional competences, which in turn have a significant effect on firm performance.

These connections are presented in Figure 8.2 in the overlapping areas between OL and KM, KM and DC, and DC and OL, respectively. In addition, the center of the Venn diagram represents the core of the learning field, the belief that organizational learning processes underpin changes in routines and resources, that is, in the knowledge base of the firm. It should be noted that the sizes of the circles and geography of overlap are not intended to capture depth or breadth. When we consider the unique contributions of each field, we find that KM has contributed a great deal to the epistemological and ontological basis of knowledge and knowing. OL contributes depth in the multilevel processes that underpin changes in cognition and behavior and these processes are the same ones that underpin dynamic capabilities, knowledge management, and absorptive capacity. Dynamic capabilities contribute largely to the type of activities to which we can apply these learning processes in the drive for competitive advantage. The unfortunate shortcoming in each of these literatures has been the predominant failure to draw on these associated strengths as each seems to try and ‘reinvent the wheel.’ We hope Figure 8.2 provides an opportunity for researchers to elevate organizational learning processes as the fundamental elements underpinning knowledge management, dynamic capabilities, and absorptive capacity constructs and theories.

Absorptive capacity and the OL, KM, and DC fields

The case of absorptive capacity is special in the sense that we see this concept as overlapping with different aspects of the OL, KM, and DC fields. AC is a subset of organizational learning because it focuses on the value and assimilation of one specific type of learning: learning from external sources. AC is also part of KM and OL because the different dimensions of AC are OL or KM processes (e.g. evaluating, assimilating, and applying external knowledge). Finally, AC has been positioned as a dynamic capability that is instrumental in changing and reconfiguring routines and resources.

We see absorptive capacity as a research area that builds on concepts from OL, KM, and DC fields, and that is specialized on the strategic value of learning and knowledge for technology innovation. An example of a study that makes AC’s foundations in the OL and KM fields explicit is recent work by Nemanich et al. (2010), who incorporate research on the micro-level learning and knowledge processes into each of the AC dimensions and link AC dimensions to Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) knowledge spiral and to Crossan et al.’s (1999) 4I Framework of Organizational Learning (Crossan et al., 1999). We summarize these two models here briefly before making the connections to AC.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) suggest four basic modes of knowledge creation: socialization, externalization, internalization, and combination; and four types of content: sympathized knowledge, conceptual knowledge, operational knowledge, and systemic knowledge. Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, and Lampel (1998) summarize these ‘four modes of knowledge conversion:’

Socialization describes the implicit sharing of tacit knowledge, often even without the use of language—for example, through experience . . . Externalization converts tacit to explicit knowledge, often through the use of metaphors and analysis—special uses of language. Combination combines and passes formally codified knowledge from one person to another . . . Internalization takes explicit knowledge back to the tacit form, as people internalize it, as in ‘learning by doing’. Learning must therefore take place with the body as in the mind.

Mintzberg et al. (1998:211)

In their 4I framework of Organizational Learning, Crossan et al. (1999) argue that learning takes place on the individual, group, and organizational levels, and that four sub-processes link the three levels, involving both behavioral and cognitive changes. According to this model, the process of OL can be conceived as a dynamic interplay among the organization belief system, the behaviors of its members, and stimuli from the environment, where beliefs and behaviors are both an input and a product of the process as they undergo change. Mintzberg et al. (1998) summarize the four sub-processes embedded in the 4I framework:

Intuiting is a subconscious process that occurs at the level of the individual. It is the start of learning and must happen in a single mind. Interpreting then picks up on the conscious elements of this individual learning and shares it at the group level. Integrating follows to change collective understanding at the group level and bridges to the level of the whole organization. Finally, institutionalizing incorporates that learning across the organization by imbedding it in its systems, structures, routines, and practices.

Mintzberg et al. (1998: 212)

Nemanich et al. (2010) argue that the first two dimensions of AC, the capabilities to evaluate and assimilate external knowledge, are highly cognitive in nature, and thus depend on the intuition and interpretation of individual team members (Crossan et al., 1999). Interpretation is also associated with Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) externalization process. For Nemanich et al. (2010), the collective assimilation capability requires that the unique external knowledge gathered externally by an individual be shared among others through social interpretation processes for integration at the team level. In the 4I framework of OL, Crossan et al. (1999) describe interpretation as the process of achieving a shared understanding of knowledge by reducing equivocality among cognitive maps held by team members. Shared cognition is also related to Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) socialization and combination processes. Finally, Nemanich et al. (2010) argue that the capability to apply external knowledge requires both cognitive skills and the collective behavioral skills that are essential to team task effectiveness, such as decision making and problem solving. Crossan et al. (1999) describe the process whereby teams make mutual adjustments and take coherent collective action as integration, which is a learning process of teams rather than individuals. Integration is closely associated with the notion of internalization proposed by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995).

Building on the conclusions from this initial review, the following section presents propositions that relate OL, KM, DC, and AC to firm performance.