A ‘Holistic’ Framework of Dynamic Capabilities

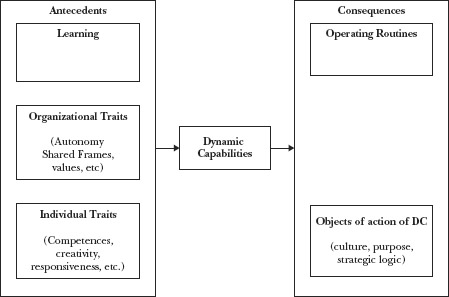

The distinction made above between the (relatively) well-known characteristics of DC connected to the adaptation of behavioral patterns, and the hitherto under-explored notion of DC connected to the adaptation of antecedents to behavioral change is at the core of our proposed contribution. We use the word ‘holistic’ to indicate that the conceptual framework developed considers both notions of DC, those focused on the adaptation of firm behavior (operating capabilities in particular) and those focused on the adaptation of behavioral antecedents, such as cognition (e.g. cognitive frames) and motivation. The framework proposed is considered ‘holistic’ (complete) also because it aims to encompass, albeit in highly abstract and general terms, all the general categories of explanations for the formation and evolution of DC. As such, it will try to move beyond the role of learning processes highlighted by prior literature (Zollo and Winter, 2002) and consider the role of both organizational as well as individual traits in shaping the development of DC. Finally, the proposed framework aims to be holistic also in terms of identifying both the evolutionary and the technical aspects of performance highlighted by Helfat et al. (2007) to include notions of appropriateness in the direction of change (evolutionary fit), as well as of economic efficiency in the change process itself (technical fit, i.e. with value produced larger than the costs necessary to produce it). The overall logic of the framework is summarized in Figure 24.1.

Figure 24.1 A Model of DC Antecedents and Consequences

The analysis is divided into three steps. We first focus on the mediations of behavioral and non-behavioral objects of change in shaping both the firm’s evolutionary and technical fit. We then move on to consider the broad sets of factors that might distinguish one firm’s ability to develop DC from another, over and above the notion of learning capabilities, which have already been discussed in the received literature. Finally, the dynamic nature of the framework is considered, including potentially important feedback loops that might shed new light on the advantages in order to expand the notion of DC to include the non-behavioral aspects of organizational change.

Mediating factors on the DC-performance link

The central point of departure from the received literature consists in the observation that, to fully capture the impact of DC on evolutionary and technical fitness, it is necessary to consider not only operating routines and organizational processes as objects of change, but also changes in cognitive and emotional/motivational traits of individual members of the organization, as well as shared cognitive and emotional/motivational traits among groups of individuals (eventually, albeit rarely, including all the members of the firm).

For instance, the absence of change in the case of Polaroid when faced by a technological discontinuity in the business of digital imaging was related to cognitive inertia (Tripsas and Gavetti, 2000) connected to the implicit framing of the competitive challenge facing Polaroid, and of its strategic response. It was Polaroid’s inability to adapt its managers’ mental models that led to the origins of the failure to adapt its competitive strategy and consequent operating routines to the rise of digital imaging. Similarly, Kodak and Anderson Co. have not been able to leverage the cognitive flexibility of their employees while coping with disruptive change respectively in the business of imaging and the business of consulting (Henderson and Kaplan, 2005). More recently, and along this line of reasoning, Danneels (2010) has described the inability of Smith Corona to face disruptive change in its typewriter business as an absence of dynamic capabilities specific to the adaptation of cognitive frames, first, and consequently of operating processes.

All the previous examples have in common a definition of cognition in terms of ways to frame the strategic challenge facing the firm (Schneider and Angelmar, 1993) and of the strategy connected to facing such challenge. Other cognitive traits that can be subject to systematic change processes through the deployment of DC might have to do with organizational identity traits connected with answers to questions like: what is the purpose of the company’s existence and what defines or limits its role(s) within its social and economic environment (organizational identity)? What does it stand for (organizational values)? How are things done over here (organizational culture)?

In addition to all these cognitive dimensions, upon which the extended notion of DC that we have proposed displays its effects, there are several emotional and, in particular, motivational dimensions that also require specific attention. Gottschalg and Zollo (2007), for example, identify the mechanisms through which firms might learn to manipulate motivational levels of their managers and employees, encompassing explicit, normative implicit, and hedonic implicit motivations (Lindenberg, 2001). They also identify conditions under which these types of DCs generate sustainable competitive advantage, as well as conditions in which the advantage is not likely to be sustainable.

Besides motivational processes and connected organizational competencies for their static deployment as well as dynamic adaptation, the study of non-behavioral and non-cognitive objects of organizational change can be particularly vast, even though poorly appreciated. Consider all the dimensions of emotional traits that characterize in a stable, albeit not fixed, manner any organization. Positive effects (happiness, joy, excitement, etc.) are typically connected not only to stronger motivation to pursue the interests of the firm, but also to all sorts of intermediate goals such as creativity and innovation, capability development and transfer, and socially responsible decision making (Crilly et al., 2008). Negative effects, such as anger, frustration, and sadness (to name just a few), are typically connected to the opposite type of outcomes generated by positive effect. However, the causal linkages might be neither symmetric nor linear. For example, a moderate level of frustration is normally considered to be necessary in order to stimulate search for improved solutions, whereas anger with the status quo might be conducive to positive energy towards the initiation and/or acceptance of change. The key question, which has received very limited attention so far by scholars (Huy, 1999) concerns the development of processes dedicated to the change of these emotional traits within firms. DCs specialized in the manipulation of emotional traits are typically very difficult to observe in firms, but most of the processes connected with the internal communication function are geared towards the (more or less deliberate) adaptation of emotional traits.

Factors explaining the origins and the evolution of dynamic capabilities

The question related to the origins and development of DCs has received increasing attention from scholars, as the debate on the definition and content of DCs converged to some consensus (Zollo and Winter, 2002; Winter, 2003; Helfat et al., 2007). The most immediate explanations have to do with learning processes of a different nature that are expected to be at the basis of the development of any organizational capability, whether of dynamic nature or not. They have to do, for instance, with experience accumulation and learning-by-doing mechanisms, with deliberate investments in learning processes such as knowledge articulation and codification activities, as well as with vicarious learning and other imitative processes.

For the purpose of this chapter, however, we will focus on other factors that are not specifically related to learning processes but might nonetheless influence the ability of firms to undertake change processes through the development and deployment of DCs. Their discussion can be organized with respect to the level of analysis at work: organizational versus individual traits.

Organizational traits

To date, the conceptual and empirical effort directed towards the unbundling of the genesis and evolution of DC has been primarily devoted to studying the organizational base of the actions behind sustained product innovation. In an inter-industrial analysis of several product development projects, Leonard-Barton (1992) identified individual skills, technical systems, managerial systems, values, and norms as the key interrelated dimensions of the dynamics of sustained product innovation. Tushman and O’Reilly III (1997) also linked the nature of capabilities specific to the management of continuous product development to similar organizational variables and highlighted how an ambidextrous organization might prevent a firm falling into the trap of too much exploitation with no exploration. Verona and Ravasi (2003) found analogous results in the longitudinal analysis of a leading firm in the hearing-aid industry. According to their study, continuous product development was based on the ability to create, combine, and reconfigure knowledge. These three knowledge-based processes relied on the interconnection among organizational variables (namely, actors, physical resources, structure and systems, and organizational culture) and the ability of the firm to let them coexist within a loosely-coupled structure. Likewise, the work of Colanelli-O’Connor (2004) has recently investigated the organizational antecedents to the development of DCs specific to the management of radical product innovation. Findings show that these antecedents are deeply rooted in a system based on an identifiable organizational group, the practice of project management (a clear role system and a clear system of objectives), and a loosely-coupled organization, on an appropriate endowment of skills and talent, and on a (somewhat loosely defined) strong leadership. By comparing non-innovative and innovative organizations in mature industries, Dougherty, Barnard, and Dunne (2004) present an empirically-grounded theory that explains how the DC for sustained product innovation is closely linked to the organizational dynamics of power and control. Finally, Blyler and Coff (2003) point also to social capital as a key variable at the basis of a DC’s formation and, consequently, at the basis of rent appropriation.

Beyond the sustained innovation context, there is comparably less work dedicated to the development of DCs in the management of organizational tasks of similar strategic importance, such as the selection, negotiation, and integration of corporate acquisitions, or the management of internal change geared towards the integration of principles of social and environmental (in addition to economic) sustainability. The reason why these other contexts might be very important for the development of the study of DC is that the management of M&A processes and the integration of social and environmental sustainability are organizational challenges that require particular attention to non-behavioral objects of the change process, such as the ones highlighted earlier: shared cognitive frames, beliefs and values, as well as collective emotional and motivational dynamics.

To illustrate, consider the recent evolution of the M&A literature specific to the problem of explaining performance variations studying the effects of experiential (Haleblian and Finkelstein, 1999; Hayward, 2002) and deliberate (Zollo and Singh, 2004) learning processes as antecedents to DCs specific to the management of organizational change related to the post-acquisition integration phase. What has been significantly under-explored, though, is the influence of other firm traits as antecedents of these specific types of DCs. What distinguishes some of the most successful acquirers from the others is still a matter of discussion in academic as well as practitioner debates, but it seems clear that it cannot be reduced to superior learning practices. By way of example, Charles O’Reilly’s (1998) case on Cisco Systems focuses on specific organizational structures and HR management practices to explain Cisco’s ability to integrate successfully high-tech start-ups and to retain the vast majority of their founders. In another example, GE Capital’s competence in integrating acquired companies in the financial services sector is attributed to the development of innovative organizational arrangements, for example the novel role of ‘integration manager’ in a process leadership position, coupled with the business leader in the specific organizational unit of GE (see Ashkenas et al., 1998), and other process-specific innovations that are rooted in GE’s organizational capacities to attract, motivate, and develop management talent, as well as in cultural traits that favor the emergence of managerial innovation.

The third context that we want to offer as illustrative example of DCs that could help identify the role of organizational traits in the evolution of these change capacities has to do with the significant efforts that an increasing amount of companies across industries and countries are making to understand and cope with the increasing demand by several types of stakeholders (employees, customers, suppliers, local communities, and, recently, even shareholders) to integrate principles of social and environmental sustainability within their operations, their strategic decision-making processes, and, eventually, even in their cultural fabric (Freeman, 1984; Donaldson and Preston, 1995; Blair and Stout, 1999; Freeman et al., 2010). Almost by definition, responding to these challenging expectations requires the development and deployment of DCs specific to the change of operating routines related, for instance, to the interactions with suppliers, customers, and local authorities in the communities where the firm operates. More challenging, and core to the argument in this chapter, is the change challenge connected to the more subtle aspects of the organization: the cognitive mindsets and shared beliefs that identify the purpose of work within the organization and the way it is supposed to compete and thrive, the cultural traits that could facilitate or hinder the openness to inclusion of stakeholders in the strategic decision-making processes of the firm, the motivational dynamics that affect (and are affected by) not only the system of incentives but also the type of social norms and of organizational identity traits that characterize the firm.

Individual traits

The development of this broader and more holistic notion of DC that encompasses the firm’s ability to change not only its operating capabilities and resources, but also the other non-behavioral aspects of the organization that might influence sustainable performance, is also influenced by characteristics of individual traits. In fact, it is worth noting that some of the organizational traits highlighted by the literature on sustained innovation, such as skills, talent, and leadership, are really individual rather than collective constructs. In general, however, there is a broad recognition that human agency is fundamental to the explanation of the quality and the performance outcomes of the new product development process. Indeed the effectiveness and efficiency of the development of new products has been shown to be a direct consequence of the actions performed by project leaders and team members of new product development projects, senior management involved in new product development decisions, as well as customers and suppliers involved in the process (for reviews, see Brown and Eisenhardt, 1995; Verona, 1999). For instance, Krishnan and Ulrich (2001) reviewed research in product development with respect to the sequence of decisions made during the new product development process. This business process, which they consider a ‘black box,’ involves hundreds of decisions. Leveraging solely the literature in decision science or operations management, the authors identified in particular thirty major decisions made within organizational units dedicated to product development.

The decision-making activity behind new products and the role of human agency in the process give room to the importance of individual traits such as cognitive frames and beliefs, emotions, motivations, and identity. For instance, the recent work by von Hippel (2005) has shown how the alignment between the manufacturers’ development process activities and customers’ values favors the emergence of new products. Similarly, in the case of Ducati it has been shown how the alignment of values and norms and, more generally, of identity favors the exchange of knowledge between customers and members of the new product development team in the community of creation of new products called Tech Café (Sawhney et al., 2005).

With respect to the role of cognitive traits, recent work has shown their relevance in relation to opportunity recognition for entrepreneurial ventures (Shane and Ulrich, 2004). At the same time, though, Cardon et al. (2009: 517) show the importance and the positive role of entrepreneurial passion as a driver of opportunity recognition, pointing to the need to build a comprehensive (‘holistic’) model of opportunity recognition that encompasses both the cognitive and the emotional processes in human psyche. Beyond opportunity recognition, recent work focused on the role of motivation of entrepreneurs and team members in new ventures for the quality of new product development (Shane and Ulrich, 2004). With respect to psychological traits of individuals involved in new ventures, Hmieleski and Baron (2009), for instance, demonstrate how dispositional optimism (the tendency to expect positive outcomes even when they are not justifiable) is negatively related to the performance of their new ventures; they also show how this relationship is strengthened when moderated by industry dynamism and past experience.

These contributions exemplify, should it be necessary, the significant potential for the future development of our understanding of innovation processes provided by a serious investment in the exploration of the individual level antecedents to DC, sometimes referred to as the micro-foundations of innovation processes. For what concerns the M&A context, the discourse on the micro-foundations of M&A processes and performance is still in its embryonic stage. With very few exceptions, the literature has tackled the quest to understand M&A-related capabilities as a fundamentally collective phenomenon. This is understandable, since a corporate acquisition typically involves all the organizational functions of the acquired organization and, in all cases of operating, cultural or at least structural integration, the corresponding functions within the acquiring unit. However, the development of a firm’s ability to handle the most complex phases of the M&A process, which are normally considered to center on the integration phase (Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991), might be heavily influenced by individuals playing a particularly important role in these processes. In most cases of a sophisticated acquirer (Cisco Systems, Intel, GE Capital, Electrolux, Dow Chemical, to name but a few), the individuals heading the corporate development unit will shape the processes and the decisions characterizing their firm’s approach to the integration phase in line with the objective requirements of the type of firms acquired and the rent generation logic of each acquisition. More subtly, they will also shape those processes and decisions in alignment with their own convictions (derived from their cognitive representations and frames) about how an acquisition should be handled, in alignment with their psychological dispositions vis-à-vis decision-making processes in general (e.g. consensus orientation), the emotional components of the integration process (e.g. resistance to change, uncertainty-driven anxiety, frustration and anger, hope and excitement, etc.), and the motivational dynamics that play such a significant role in the alignment and integration process ( Jemison and Sitkin, 1986; Buono and Bowditch, 1990). However, what has not been tackled at all in the received literature is the role of the corporate leader in shaping, for better or worse, the way the firm learns how to cope with the complexities of the post-acquisition integration phase (Fubini et al., 2006). The authors identify several ways in which the corporate leader can influence the post-merger processes, including the way the firm learns to handle the key challenges during and after the completion of the integration phase. Despite these initial results, however, this line of work is still very much an open field since there is a lot more to understand on how individual traits of leaders and corporate development executives might influence the development of M&A-related DC.

In the third context considered, the one related to the embedding of social and environmental sustainability principles within the firm’s operations, strategies and cultural traits, the study of firms’ capabilities related to those internal change processes has yet to materialize in any empirical (or even theoretical) result. To the best of our knowledge, there are only a few case studies that attempt to unpack the learning challenge related to both sense making on the direction of change required and to enacting the internal changes against the resistance of internal and external stakeholders. Zadek (2004), for example, studied Nike’s painful experience following the sweatshop scandal in the mid-1990s to conceptualize the challenge in terms of internal and external learning and change processes, but that can only be considered an initial exploration in largely uncharted territory. The field needs to begin a significant investment in the identification of the factors explaining superior performance in adapting internal processes to the evolution of multiple key stakeholders’ needs and interests, and to refocus its attention to external stakeholder engagement practices towards the analysis of internal learning and change processes (Zollo et al., 2007). In that sense, the research agenda of scholars focusing on the study of social and environmental sustainability converges and overlaps with the one pursued by the larger field of scholars with a general interest in organizational learning and change, and, more specifically, in the origins and consequences of DC.

Dynamics and feedback loops

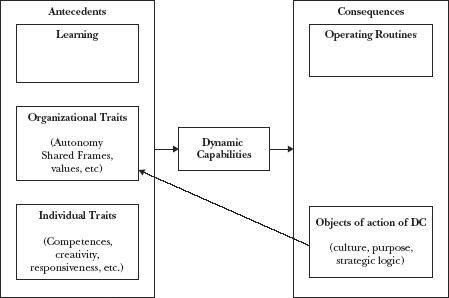

The focus of our argument above has been on the need to extend the received notion of DC to encompass a broader set of objects of learning and change (i.e. the non-behavioral aspects of the firm, beyond operating routines) as well as of antecedents to the learning and change process itself (organizational and individual traits, beyond learning processes). The call for extension of the theory of DC is not motivated solely by the need to build a more comprehensive model of organizational evolution, though. It is fundamentally driven by the observation that by extending the model to the dynamics of non-behavioral antecedents and consequences of DC, we might be able to observe and describe qualitatively different features of the dynamic interaction among the variables considered.

To illustrate, consider the version of the model exemplified by the sequential chain of causation from learning to change (i.e. DC) to operating routines proposed by Zollo and Winter (2002). In this received version of the story, the causation can only go in one direction, with learning processes influencing the development of capabilities (dynamic as well as ‘static’), and with DCs influencing the development of operating capabilities and resources. If one, however, considers the extended version of the model proposed, the unidirectionality in the causation chain might not apply any more. More specifically, the ‘holistic’ notion of DC will influence the evolution of organizational traits that are in turn likely to influence at least some of the non-behavioral factors, at the organizational as well as individual level, that shape the ability of the organization to produce DC. It is the nature of these feedback loops that might allow future scholars to build a more complete picture not only of how business organizations evolve over time, but also (and most interestingly) about the interdependence between the evolutionary processes at the organizational and the individual levels (Figure 24.2).

Figure 24.2 The Feedback Loops

To illustrate, consider the case of DCs specific to the integration of sustainability within the various dimensions of the firm, both behavioral (i.e. operating routines) and non-behavioral (e.g. cognitive framing of the strategic challenges, cultural traits, and emotional dispositions) in nature. Whereas it is difficult to imagine that changes in operating routines will influence ‘backward’ the development of the DC that might have created and eventually shaped them, that is quite possible when the influence of DC on cognitive and emotional components of the firm is taken into consideration. For instance, consider a firm that has developed a DC in adapting the cognitive frames of its managers related to the purpose of existence of their company to include the improvement of the well-being of the communities in which it operates. That firm will not only see its management change their decision-making patterns to include, for example, an explicit evaluation of the social and environmental consequences of their decisions, and perhaps to suggest process adjustments aimed at engaging the most relevant stakeholders in the decision itself. Most likely, that firm will also see its managers invest in learning to change internal processes, motivations, emotional traits, and social norms, thereby developing and upgrading the firm’s collective DC specific to these sustainability domains. Ditto if the objects of change in the DC are the psychological dispositions of managers and entrepreneurs towards more caring for and openness with, for example, the key stakeholders of the enterprise (employees, customers, partners, and the local communities) in addition to the shareholders. Again, those dispositions might trigger learning processes which will further develop the same DC that initiated or developed them, creating, therefore, a positive feedback loop, a potential virtual cycle between holistic notions of DC and the non-behavioral objects of change. Note, by the way, that the presence of a positive loop does not necessarily mean that firms will spiral up (or down) to infinite levels of openness and caring for stakeholders (or lack thereof). The loops could simply follow each other with smaller and smaller magnitudes, therefore reaching a steady state in this dynamic system at high levels of DC, high levels of openness and inclusiveness in strategic decision making of stakeholders, and eventually high levels of evolutionary fit (assuming that openness and inclusiveness are part of the expectations and interests of stakeholders).