Knowledge in Three Network Types

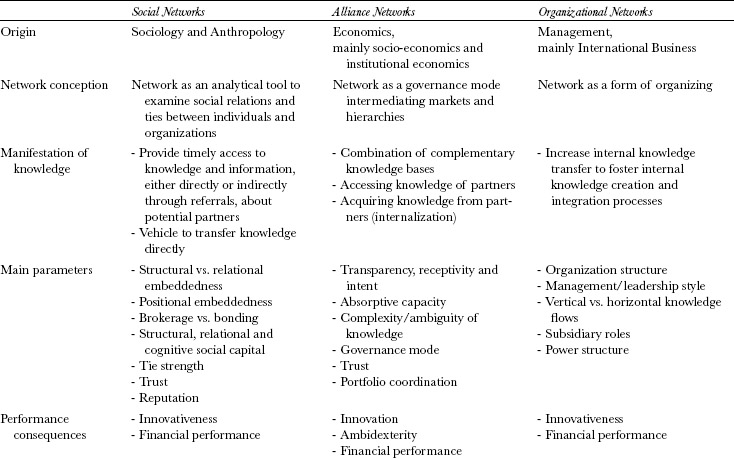

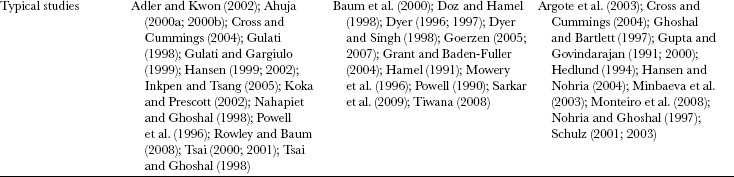

The study of how various types of networks foster the management and organization of knowledge has been conducted under three banners: social networks, alliance networks, and organizational networks. The origins of the different research streams, as well as their applications, contributions to knowledge research, main parameters, and performance implications are listed in Table 22.1.

Social network perspective

Having its origins in sociology and anthropology, the study of social networks goes by the notion that ‘the structure of any social organization can be thought of as a network’ (Nohria and Eccles 1992: 288), and that the actions of network actors are shaped and constrained because of their position and embeddedness in the network (Nohria, 1992). Or, as Lincoln (1982: 26) argues, ‘to assert that an organization is not a network is to strip of it that quality in terms of which it is best defined: the pattern of recurring linkages among its parts.’ A social network perspective entails not only that all organizations are social networks, but also that the environment is a network of other organizations. With that, social network analysis provides management scholars with a tool to examine relations between actors, ranging from individuals and units (Brass and Burckhardt, 1993; Tsai and Ghoshal, 1998) to firms and groups of firms (Rowley et al., 2000; Wasserman and Faust, 1994), in which ‘network’ is essentially a construct created by the investigator. In that sense, it has also led to the economics critique that firms are far from atomistic agents but embedded in networks that influence competitive actions (Granovetter, 1985; Uzzi, 1997).

Social network research centers on the ties between actors and focuses on their content and benefits. Tie content may consist of assets, information, and status (Galaskiewicz, 1979). With the emergence of knowledge as a strategic asset (Grant, 1996), much research in social networks has come to center on how ties facilitate the seeking and subsequent transfer of knowledge. Tie benefits occur in the form of access, timing, and referrals (Burt, 1992). Access denotes the role of network ties in providing actors with access to parties and their knowledge. Timing allows actors to obtain information and knowledge sooner than actors without contacts. Referrals involve the provision of information by actors in the network to the focal actor on available opportunities.

Since the benefits of ties are critical to understanding how social networks influence seeking and transferring knowledge, a body of research has begun to focus on social capital, which involves ‘the actual or potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed by a social unit’ (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998: 243). Social capital involves the goodwill others have towards an actor, which is a valuable resource providing benefits in the realm of obtaining influence, facilitating solidarity, and getting superior access to information and knowledge (Adler and Kwon, 2002). Although organizations may benefit from having social ties, not all organizations possess comparable levels of network resources. Such heterogeneity depends on specific features of social networks that determine the value of social capital.

Main parameters

A common theme among social network studies is to describe the network position and ties of an actor in terms of its structural and relational embeddedness in the network (Gulati and Gargiulo, 1999; Uzzi, 1997). In studies of social capital an equivalent distinction is made to indicate the value actors derive from their position in the network. In addition to structural and relational social capital, Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) forward cognitive social capital as a third dimension. Structural capital refers to the structure and configuration of the network in terms of (mutual) contacts to one another. It involves the number of social ties maintained by an actor and the centrality of an actor in its network. Relational capital describes the kind of relationships actors have developed, and manifests itself in the strength of ties. Tie strength reflects the closeness of a relationship between partners, and increases with frequency of communication and interaction (Hansen, 1999). Cognitive capital indicates the resources that provide shared representations and systems of meaning, and is embodied in shared language and codes that facilitate learning, and common understanding of collective goals (Inkpen and Tsang, 2005; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998).

In a study on the origins of networks, Gulati and Gargiulo (1999) suggested that, in addition to the structural and relational dimensions of embeddedness, an actor’s positional embeddedness is an important characteristic. It indicates the extent to which actors derive information benefits from the ties and the network itself. Since network actors not only differ in number but also in characteristics, Koka and Prescott (2002) differentiated such benefits into volume, richness, and diversity of information and knowledge. Volume and richness refer to the quantity and quality of knowledge and information respectively. Diversity emphasizes the variety of knowledge and information available to network actors. These dimensions contribute to reconciling the different views as to how networks contribute to knowledge acquisition, innovation, and performance.

Two views have emerged as to which network typology creates most benefits when it comes to knowledge transfer (Burt, 1997; 2000; Coleman, 1988; Uzzi, 1997). The first view emphasizes the benefits of maintaining a strong structural position, and has been referred to as brokerage theory. It puts much emphasis on bridging social capital, which alternatively has been labeled linking or external social capital (Adler and Kwon, 2002). It stresses that the information benefits accruing to an actor are highest when that actor is central to the network and has a key role in bridging and linking multiple smaller actor networks between which no direct links exist. Every piece of information and knowledge must go through the central actor if it travels from one network to the other, making the central actor structurally autonomous and bridging structural holes. Brokerage theory views the network as an opportunity for entrepreneurs to exploit by seeking partners that are non-redundant and bring new and diverse information. Such diversity leads to firm heterogeneity in the development and acquisition of competitive capabilities (McEvily and Zaheer, 1999), as well as in the generation and appropriation of rents (Blyler and Coff, 2003).

The second view has been referred to as closure theory and takes that actors in a dense network enjoy most benefits from the network. Actors in a dense network share the same direct and indirect ties and are structurally equivalent. Because returns on investments in the resources needed to maintain the network are more certain, densely connected actors are likely to develop strong ties to redundant others. In that sense, this view focuses more on maintaining strong relational ties and it centers on bonding social capital, which has also been cited as communal or internal social capital (Adler and Kwon, 2002). A strong relational tie increases the opportunity to share richer information. The development of bonding positions also entails that the network is reproduced due to its value in preserving the social capital of an individual.

An ongoing debate has revolved around whether brokerage opportunities derived from a centralized position or closure accruing from relationally embedded ties foster knowledge transfer (Burt, 2007; Levin and Cross, 2004; Uzzi, 1997). Studies distinguishing between structural and relational properties of social networks show how these differences may manifest in specific contexts (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). Gargiulo and Benassi (2000) found that actors positioned in brokerage roles were better able to adapt to environmental changes, and that the network closure produced by cohesive ties fostered stability. Likewise, Lyles and Schwenk (1992) assert that a loosely coupled knowledge structure fosters adaptation. In contrast, the studies of Ahuja (2000a), Kraatz (1998), and Walker et al. (1997) found supporting evidence that cohesive and strong ties, which are information-rich, fostered adaptiveness by increasing innovation. Hite and Hesterly (2001) found that in the early growth stages of firms networks are likely to be dense, closed, and relationally embedded. In later growth stages, firms are likely to exploit structural holes in a balance of embedded, arm’s-length relations. Likewise, Soda et al. (2004) found that the value of brokerage and closure is dependent on whether a structural position is current and a relational tie has proved its value in the past.

In an influential study of inter-unit knowledge transfer, Hansen (1999) found that one of the moderators influencing the value of a strong structural or relational position is the complexity of knowledge. He concluded that cohesive ties are less likely to allow firms to adapt to changes in coordination requirements, because strong ties are prone to network inertia and nodes in the network stay within their network. However, complex knowledge may contribute to joint problem solving (McEvily and Marcus, 2005) and to the novelty of innovation, and thus adaptation (cf. Galunic and Rodan, 1998). Social capital can therefore act as a resource, but also as a constraint in enforcing norms and values among network members and in developing political and cognitive lock-ins (Grabher, 1993). Hansen (1999) found that a trade-off exists in the use of ties when searching for relevant knowledge and transferring knowledge. This search-transfer problem indicates that weak ties are most effective for searching knowledge and transferring non-complex, easy-to-codify knowledge, and that strong ties characterized by close interaction and communication are necessary for transferring complex, difficult-to-codify knowledge. A similar result was found by Uzzi and Lancaster (2003) who argue that publicly available, hard knowledge is best transferred through an arm’s length contract while the transfer of private knowledge benefits most from an embedded tie.

Since studies on networks and knowledge have been inconsistent in the measurement of network variables, recent studies have started to explore the extent to which the structural features of brokerage and closure act as opposites in explaining knowledge search and transfer, and the extent to which they associate with the relational feature of tie strength. Often prior studies have inferred structural properties from a relational variable (e.g. Hansen, 1999). Reagans and McEvily (2003) found that both brokerage and closure ease the transfer of knowledge independent of complexity. The evidence of a later study (Reagans and McEvily, 2008) indicates that structural and relational properties of networks are mutually reinforcing and promote both knowledge search and transfer but in different ways. Likewise, Tsai and Ghoshal (1998) found that both structural and cognitive social capital contribute to relational social capital, which subsequently increased knowledge combinations. In a study relating knowledge and power, Reagans and Zuckerman (2008) also show that non-redundancy generates greater potential returns, but that these returns are balanced by the more certain returns that result from having redundant partners. Both brokerage and closure serve as a locus of performance improvement and innovation because they provide access to different types of knowledge that may be unavailable otherwise. Cross and Cummings (2004) found that a strong structural position may account for both current and future performance in that centrality in the information networks facilitates access to current knowledge and centrality in the awareness network fosters the opportunity to act on future opportunities. Hence, both structural and relational capital have been suggested to provide an effective mechanism for seeking and transferring knowledge, as well as the creation of learning capabilities (Adler and Kwon, 2002).

Complexity of knowledge and the different dimensions of social networks and capital have been instrumental yet not sufficient to explain the ways in which networks contribute to knowledge transfer. An important moderating characteristic is the absorptive capacities of the actors involved in the exchange relation. Absorptive capacity is built on prior knowledge endowments: the more knowledge a firm possesses in a certain knowledge domain, the easier it is to learn new things in that domain (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990). Since studies of social network often take the dyad or network level of analysis, the role of absorptive capacity is especially salient. At the dyad level, absorptive capacity is relative (Lane and Lubatkin, 1998) and partner-specific (Dyer and Singh, 1998). Because the knowledge bases of the actors differ, the capacity to absorb knowledge from one partner is different from the capacity to absorb knowledge from another partner. When the knowledge stocks of actors in a network overlap, learning and knowledge transfer are fostered. An increasing number of studies found that relatedness in technologies, knowledge, and resources facilitates the creation of new linkages between actors, the transfer of knowledge and innovation (Ahuja, 2000a, 2000b; Stuart, 1998; Tsai, 2000).

Another characteristic examined in a variety of studies is the role of reputation and trust. Reputation primarily influences the search for knowledge, as it facilitates the creation of new linkages. As Granovetter (1985: 490) argues, individuals have ‘widespread preference for transacting with individuals of known reputation’. Prestigious firms that have a track record of producing significant innovations and firms positioned in crowded network pockets where many innovations take place have more opportunities to create new ties (Stuart, 1998). Firms that have no information about the capabilities and intentions of actors in the network will first look for firms that have established a good reputation, because this creates a basis of trust. As such, trust is found important to network formation and maintenance: trust preserves the network through repeated ties and the creation of relational capital, which contribute to the development of trust (Gulati, 1995; Kale et al, 2000).

Alliance network perspective

Alliance network research focuses on network organization as a governance mode interjacent to market organization and firm organization and has its main roots in the economics discipline, mainly transaction-cost economics and socio-economics. Following transaction cost theorizing, firms choose an alliance when the costs they incur in negotiating, enforcing, and monitoring contracts are lower in cooperation than those associated with buying assets on the market and with making assets within their own firm (Powell, 1990; Williamson, 1975, 1985). A large part of alliance research has traditionally focused on joint ventures and strategic alliances that allow firms to reduce risk, to share costs, to enjoy economies of scale, and to block competitors. Additionally, firms use alliances as a means to access complementary resources and knowledge and to learn from their partners (Barringer and Harrison, 2000; Doz and Hamel, 1998; Kogut, 1988).

From a knowledge perspective, firms enter into alliances (1) to gain access to new knowledge and pool the knowledge bases of the partners involved or (2) to internalize the knowledge of the partner (Grant and Baden-Fuller, 2004; Inkpen and Dinur, 1998). Firms may have knowledge bases that are complementary or co-specialized so that innovation and competitive advantage only emerge when the knowledge of the alliance partners is brought together (Dhanaraj et al., 2004; Dyer, 1996, 1997; Larsson et al., 1998; Lavie, 2006). Especially in turbulent and converging industries, firms’ product and knowledge domains may not be consistent. Organizations may not be able to develop products because they lack the necessary knowledge. Such inconsistencies trigger firms to look outside for knowledge. For example, Toyota cooperates with its suppliers as well as rival automotive companies in a diverse network to learn from each other and to be on the forefront of industry trends (Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000).

The emphasis in alliance research has moved from studying individual alliances at the firm or dyad level to multiple alliances in a complex network (Doz and Hamel, 1998; Goerzen, 2005). As Koka and Prescott (2002: 797) argue, ‘firms have to go beyond traditional cost-benefit analyses of particular individual alliances . . . [and] need to evaluate particular alliances not only in the context of the other alliances that they already possess but also in the context of the entire network of relationships.’ A diverse set of cooperations provides a firm access to a larger and broader knowledge base that it can tap into (Baum et al., 2000; Mitchell and Singh, 1996; Powell et al., 1996). Since using multiple alliances as a means to improve performance requires more coordination, in addition to studying alliance networks per se alliance research has come to focus on how firms configure their alliances as part of an alliance portfolio (Baum et al., 2000; Sarkar et al., 2009; Tiwana, 2008).

Main parameters

Insights into main determinants of knowledge transfer in alliance networks have emerged from two types of studies. In addition to more recent research on alliances at the network level, studies that focus on individual alliances at the firm and dyad level have enriched our understanding of the antecedents and consequences of knowledge access and acquisition in alliances. For example, in his study of eleven US–Japanese alliances, Hamel (1991) found that learning outcomes were dependent on the intent of the partners, their transparency and their receptivity. Mowery et al. (1996) found that knowledge transfers between alliance partners increase as they share a common knowledge base, and that competition moderates this relationship since firms operating in industries with the same primary SIC tended to transfer less knowledge among each other. Learning in external networks is fraught with competitive motivations (Gnyawali and Madhavan, 2001), which may result in learning races. The ability to internalize knowledge and thus the outcome of such learning races is dependent on the relative market scope of the partnering firms and the alliance (Khanna, 1998; Khanna et al., 1998). The more the scope of the alliance overlaps with the scope of the firms involved, a relatively large share of common benefits would accrue to both firms, once they have internalized each other’s knowledge and are able to co-develop new products within the scope of the alliance. Such learning within the alliance scope is likely facilitated because overlap in firm scope probably renders the knowledge bases of the involved firms partially overlapping as well, and this increases relative absorptive capacity (Lane and Lubatkin, 1998; Kumar and Nti, 1998). Partners may also appropriate permanent private benefits from the alliance, which accrue to firms when they are able to apply the knowledge they acquired to markets beyond the alliance.

In a study covering the alliances of 147 MNCs, Simonin (1999) found that ambiguity, which relates to knowledge tacitness and complexity, negatively impacts knowledge transfer. Cultural and organizational distance between partner firms is also found to negatively influence knowledge transfer, because such distance increases the ambiguity associated with inter-partner learning. Simonin’s (1999) findings suggest, however, that as alliances become older firms are able to overcome problems associated with complexity, because firms develop alternate joint problem-solving styles and partner-specific collaborative know-how (cf. Dyer and Singh, 1998; Kumar and Nti, 1998) that enable them to adapt to each other and overcome problems associated with complexity.

Distinct interdependencies and complexities inherent in tasks lead to coordination costs (Gulati and Singh, 1998). Alliances are essentially incomplete contracts. Partners face the risk of opportunistic behavior emerging and knowledge leaking (Baum et al., 2000). Such risk is dependent on the motivations of the partners, the value creation logic driving the alliance and the resources involved in the alliance. Therefore, for alliances with different purposes and in which different types of resources are involved, firms use different governance structures (Das and Teng, 2000). The choice for governance structure and the extent to which firms enjoy competitive advantage is further influenced by whether firms create relation-specific assets and knowledge sharing routines. Such assets and routines not only create idiosyncratic inter-firm linkages to combine knowledge and other resources in unique ways (Dyer and Singh, 1998; Mesquita et al., 2008).

Governance structures are differentiated by the degree of formalization (Vlaar et al., 2007) and the amount of hierarchical controls (Gulati and Singh, 1998). When appropriation or opportunistic behavior is an issue, firms were found to use joint ventures and other equity-based arrangements as governance mode (Baum et al., 2000; Gulati and Singh, 1998). Das and Teng (2000), however, suggest that firms may wish to use different governance modes depending on whether they bring property-based or knowledge-based resources into the equation. They argue that a joint venture is only worthwhile if the partner provides knowledge and the focal firm provides property-based resources, because a joint venture allows a firm to gain direct access to knowledge. A minority equity arrangement is more beneficial when the focal firm itself brings into the alliance knowledge-based resources, as a hostage without the creation of a separate entity will allow it to protect its knowledge from dissipating to its alliance partners.

Dyer and Singh (1998) argue that, in addition to the creation of formal hostages, effective self-enforced governance can occur informally through trust and reputation. Based on a study assessing whether firms in alliances finance the activities of their partners, Stuart (2003) found that the structural position of a firm in its alliance network influences the governance structure chosen in its alliances, as a structural position harbors a reputation effect and influences the knowledge potential partners have about the focal firm. As in social networks, trust is crucial in external networks and forms a substitute for price and authority as the coordination mechanism (Bradach and Eccles, 1989). Trust leads firms to make relation-specific investments and to create repeated ties with their partners and vice versa. Goerzen (2007) found evidence that forming repeated ties with the same alliance partners has a negative influence on the economic performance of firms at the corporate level, especially in uncertain environments. In that sense, he disconfirmed the transaction cost perspective that repeated ties lead to more efficient governance arrangements and mitigate challenges of acculturation and integration. While repeated ties create trust, they also lock out potential partners that possess new knowledge and may lead firms to exploit existing routines rather than exploring new ones (Zaheer and Bell, 2005). Firms need to configure their alliance network so that both diverse partners are bridged to increase innovation potential and strong relations are developed to develop integration capacity. Such a balanced network allows firms to use their alliances to both create innovation potential and realize that potential. In other words, it enables them to both explore and exploit, consequently becoming ambidextrous (Lavie and Rosenkopf, 2006; Tiwana, 2008).

Beyond dealing with partner coordination through relational governance, management of an alliance portfolio requires coordination among alliance partners. As firm boundaries blur and a firm’s alliances become part of a wider ecosystem (Iansiti and Levien, 2004), different alliance partners in a firm’s portfolio cater for the resources it does not possess. In case a firm seeks to acquire knowledge from multiple partners, it needs to develop absorptive capacity. Since absorptive capacity is dependent on a relevant knowledge base, it is inherently relative and partner-specific (Dyer and Singh, 1998; Lane and Lubatkin, 1998). In that vein, Kumar and Nti (1998) suggested that firms leverage absorptive capacity so that knowledge absorbed from one partner may increase the ability to absorb knowledge from another partner. Hence, the coordination of knowledge and strategies across a firm’s alliance portfolio increases the success of a firm (Sarkar et al., 2009).

Organizational network perspective

Research on organizational networks is mainly rooted in the management field, notably in the field of international business. An organizational network’s advantage is its ‘ability to create new value through the accumulation, transfer, and integration of different kinds of knowledge, resources, and capabilities across its dispersed organizational units’ (Nohria and Ghoshal, 1997: 208). Studies increasingly address the problems multinational firms face in transferring knowledge across their subsidiaries and in putting to effective use their distributed knowledge stocks in different locations. In that sense, they center on network organization as a feature of organizational design or as a form of organizing alternative to, for example, functional and multidivisional organization forms (Doz et al., 2001; Hedlund, 1994; Nohria and Ghoshal, 1997).

Organizational networks cater for the problem that ‘knowledge is a resource that is difficult to accumulate at the corporate level . . . [and] those with the specialized knowledge and expertise most vital to the company’s competitiveness are usually located far away from the corporate headquarters’ (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1993: 32). Subsidiaries and organizational units need to transfer knowledge among each other, because knowledge deemed valuable in one location may be valuable in other parts of an organization. When firms enter into alliance networks, little or no change takes place in internal organization. Organizational routines remain unimpaired and often prevent firms from deploying knowledge acquired externally as ambitiously internally (Ghoshal and Bartlett, 1997). These developments have triggered the emergence of an alternate corporate model that marks ‘the selective infusion of market mechanisms into hierarchy and hierarchy into markets’ (Zenger and Hesterly, 1997: 210). Alongside relying on alliances, this corporate model relies on intraorganizational networks to foster knowledge creation and integration inside a firm’s boundaries.

Typically, organizational networks make use of organic systems of management, which are characterized by dispersed knowledge, horizontal knowledge transfer, and decentralized decision making (Burns and Stalker, 1961). They also depend on projects, less bureaucracy, open communication (Thomson, 1965), and are mainly self-designing (Hedberg et al., 1976). While the foundations of organizational networks were laid down in the 1960s, in international business, organizational networks have recently gained interest and have been further examined in studies on transnational corporations (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1989), differentiated networks (Nohria and Ghoshal, 1997), integrated networks (Ghoshal and Bartlett, 1997), and metanational organizations (Doz et al., 2001). They also feature center stage in studies of organization forms such as cellular organizations (Miles et al., 1997), horizontal organizations (Ostroff, 1999), hypertext organizations (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995), and N-form corporations (Hedlund, 1994). Scholarly interest in these organizational forms has been progressing mainly because the proportion of firms with characteristics indigenous to network organization is increasing (Pettigrew et al., 2000).

Main parameters

A central theme in studies of how organizational networks influence knowledge transfer and integration is organization design. Ghoshal and Bartlett (1997) argue that the emphasis on strategy, structure, and systems so common in many organizations is changing towards purpose, processes, and people in organizational networks. Subsequent studies are indeed evident of this change as they emphasize that the most common barriers to collaboration and knowledge transfer revolve around the unwillingness and inability of people and units to share knowledge and help others (Hansen and Nohria, 2004; Szulanski, 1996; 2000). Ability and motivation are therefore central concerns of multinational corporations seeking to accumulate, integrate, and apply knowledge across different locations (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000; Minbaeva et al., 2003), especially when faced with an opportunity (Argote et al., 2003), and are more effectively addressed by focusing on processes and people.

Structure in organizational networks remains important as it shapes ability and motivation by forming the context in which processes and people operate. Since co-locating knowledge and decision rights increases a unit’s competitiveness (Doz et al., 2001; Jensen and Meckling, 1992), units in organizational networks are autonomous and granted operational and strategic responsibility. While this allows units to develop knowledge stocks attuned to local environments, units also become differentiated. Since stocks of knowledge developed by one unit may be effectively used by other units, in organizational networks integration mechanisms are in place connecting knowledge stocks through knowledge flows. Using an agent-based model, Siggelkow and Rivkin (2005) show that decentralization of decision-making power to local managers who can respond to idiosyncratic, local events and share knowledge laterally is a preferred structure when environmental turbulence increases in the face of high complexity. They also found, however, that the centralization of a hierarchical firm may be equally effective in such an environment as a select few can act speedily and decisively. Other studies suggest that the outcomes of adopting a (de)centralized design may be suboptimal and that combining hierarchy and network principles into one structure is most valuable. Networks are based on the principles of multiplication and combination rather than on the principle of division so characteristic of hierarchies (Hedlund, 1994), yet hierarchy remains indispensable to reach certain decisions quickly, to resolve disputes, and to obtain employees’ allegiance to an organization’s mission and objectives (Powell, 1990). A combination of these mechanistic and organic structures allows firms to pursue both exploration and exploitation and to become ambidextrous (cf. Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008). Insights into how and the extent to which hierarchical and network structures need to be combined into one organization are, however, still inconclusive.

In addition to formal organization, changes in management and leadership style facilitate ability and in particular motivation to transfer knowledge (Hedlund, 1994; Hansen and Nohria, 2004; Pettigrew et al., 2003). Organizational networks require a management philosophy that is evident of an organic management system in which ‘a network structure of control, authority, and communication’ (Burns and Stalker, 1961: 121) is present. A commanding and monitoring role of the senior management team is ineffective to facilitate knowledge transfer. Organizational networks are better served by senior managers that act as architects and catalysts of network processes (Hedlund, 1994). Instead of allocating resources based on formal control mechanisms, executives of organizational networks facilitate the leveraging of knowledge and resources by institutionalizing common norms and values that breed a culture of trust, reciprocity and collaboration (Ghoshal and Bartlett, 1997; Powell, 1990). As a consequence, whereas in many organizations knowledge flows are primarily vertical from headquarters to units, in organizational networks knowledge flows are also configured horizontally among units (cf. Aoki, 1986). Senior managers in organizational networks are horizontal knowledge brokers ‘linking and leveraging the company’s widely distributed resources and capabilities,’ rather than vertical information brokers (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 1993: 33).

The majority of studies have focused on how organizations influence the ability to transfer knowledge. While motivation to transfer knowledge is mainly influenced by characteristics of the organization, ability is additionally influenced by characteristics of the knowledge itself. For example, a variety of studies at the unit level found that the creation of vertical and horizontal knowledge flows in and out of a unit is dependent on whether old or new knowledge needs to be combined (Schulz, 2001), the volume of the unit knowledge base, the degree to which knowledge is codified, the extent to which knowledge is specialized (Schulz, 2003), the relatedness of knowledge (Hansen and Løvas, 2004), the absorptive capacity of the unit, the value of the unit knowledge stock (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000), and the degree of ambidexterity (Mom et al., 2007). Similar findings have been reported in other studies with regard to the role of absorptive capacity (Szulanski, 1996; 2000), knowledge codification (Zander and Kogut, 1995), and knowledge specialization (Brusoni, 2005). Studies assessing organizational characteristics facilitating knowledge transfer have focused on the richness of transmission channels (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000), integration mechanisms (Hansen and Nohria, 2004; Jansen et al., 2009), decentralization (Frost et al., 2002), incentives (Zenger and Hesterley, 1997), informal networks, and formal organization structure (Hansen and Løvas, 2004). Recently, studies have emerged examining how organizational and knowledge characteristics interrelate. For example, Szulanski et al. (2004) found that the positive effect of trustworthiness on knowledge transfer vanishes as causal ambiguity of the knowledge transferred becomes high. This negative effect may diminish when transmission channels become richer (cf. Daft and Lengel, 1986).

Cross and Cummings (2004) found that organizational structure renders some ties more important than others and may provide some actors with access to more knowledge and information. As a consequence, not every unit or subsidiary is equally embedded in an organizational network. Gupta and Govindarajan (1991) created a typology of subsidiary roles that centers on the strategic context of the subsidiary and the knowledge flow pattern involved. For example, subsidiaries that receive and distribute much knowledge are more integrated into the whole MNC network and play a central role in worldwide activities. On the other hand, subsidiaries who hardly share knowledge are likely to have the local expertise to innovate and implement knowledge and products tailored to local markets. Different subsidiaries will, therefore, differ as to their lateral interdependence, global responsibility and authority, and their need for autonomous initiative. In that sense, integrated subsidiaries will be more dependent on integrative mechanisms, corporate socialization, and communication than local players. Likewise, in integrated subsidiaries managers will be assessed on behavior more than on outcome, they need to be more tolerant of ambiguity, and their bonuses will be based more on the performance of multiple subsidiaries than the subsidiary that they are primarily responsible for.

Recently, a variety of studies have emerged examining how the power structure of an organization influences knowledge transfer. Monteiro et al. (2008) found that knowledge transfers between subsidiaries in MNCs typically occur between highly capable members. Units with expert status are likely to share more knowledge as it increases their power (Borgatti and Cross, 2003; Mudambi and Navarra, 2004). Wong et al. (2008) found that units that possess critical, non-substitutable, and central knowledge, and thus are deemed to have higher status and to be more powerful, are more likely to receive knowledge from others, but that this is dependent on the goal interdependence of the units involved. Andersson et al. (2007) found that subsidiary power is not only dependent on the importance of the subsidiary but also on the knowledge of corporate headquarters about the subsidiary’s local network. Importance of the subsidiary has two conflicting roles in that it increases the power a subsidiary can exert, but also increases the likelihood that corporate headquarters has developed knowledge of that subsidiary’s network and can lessen its power, which poses it a dilemma in that curtailing a subsidiary’s power and influence may lead to a reduction in the subsidiary’s interest in contributing to the overall performance of the MNC.