Individuals gain experiences as a result of how they live their lives and how they associate with others. This, in turn, depends on who they are as people and how they enter into these relations. If individuals are to learn from their experiences, they have to use their ability to not only contemplate the relation between their actions and their consequences, but also to relate them to their past, present, and future experiences. The provocative element in the development of experience is when there is a sense of habitual actions being upset. This feeling cannot be forced upon anybody from the outside, but must come from experience or from within the parameters of expanding experience. Dewey is aware of the aesthetics of experience and the sensation that they perfect or complete; any delight and comfort in a situation is also an experience, and knowing is just one way of experiencing (J. J. McDermott, 1973 [1981]). There is only an analytical distinction between an intellect that knows and a body that acts.

This anti-dualistic approach in Dewey’s works echoes one of the core principles in pragmatism, that is, that there are no dualisms such as, for example, psychological-physical, fact-value, culture-nature, and theory-action. Rather than understanding intellectual capacities and bodily actions as two different activities and phenomena, Dewey regards theories as tools or instruments in the human endeavor to cope with situations and events in life and to construct meaning by applying concepts in an experimental way. Some experiences may not be apprehended as knowledge, because they do not enter a sphere of communication with self and others, that is, they do not come with a verbal language. Along the continuum of experience, there is a vague transfer between non-cognitive and cognitive experience, but if learning is to occur from experience, experience must get out of the physical, non-discursive, and emotional and into the cognitive and communicative sphere. Only when individuals’ experiences turn into communicative experiences and become learning experiences can they inform future practice:

To ‘learn from experience’ is to make a backward and forward connection between what we do to things and what we enjoy or suffer from things in consequence. Under such conditions, doing becomes a trying; an experiment with the world to find out what it is like; the undergoing becomes instruction—discovery of the connection of things. Two conclusions important for education follow. (1) Experience is primarily an active-passive affair; it is not primarily cognitive. But (2) the measure of the value of an experience lies in the perception of relationships or continuities to which it leads up. It includes cognition in the degree in which it is cumulative or amounts to something, or has meaning.

(Dewey, 1916 [1980]: 140, Dewey’s emphasis)

In the Deweyan universe, there are no universal cognitive structures that shape human experience of reality. Dewey argued against Cartesian dualism and Kant’s a priori and innate to mind categories (space, time, causality, and object) as structuring human thinking. For Dewey knowledge always refers directly to human experience and the origin of knowledge is living experience and not the other way around, as if logical theorems might govern thinking (J. J. McDermott, 1973 [1981]; Putnam, 1995; Sleeper, 1986). This does, however, not mean that pragmatism rejects cognition:

thinking is a process of inquiry, of looking into things, of investigating. Acquiring is always secondary, and instrumental to the act of inquiry. It is seeking, a quest, for something that is not at hand

(Dewey, 1916 [1980]: 148)

It is important to specify that it is a different kind of knowledge that Dewey talks about to that in the individual perspective. In the individual perspective, knowledge is something that attempts to represent the world while in the Deweyan perspective it is an answer to a problem. Thus, Dewey tries to discriminate between knowledge as propositional knowledge, which is a part of inquiry processes, and knowledge or warranted assertions, that is, the result of the inquiry process that is fallibilistic in nature (Dewey, 1941 [1988]).

In pragmatism, ideas, theories, and concepts, that is different forms of thinking and abstraction, function as instruments for actions. In one of his later works co-authored with Arthur Bentley, Dewey writes of the practice oriented function of thinking as a tool applied by ‘men (sic!) themselves in action’ (Dewey and Bentley, 1949 [1991]: 6). The nature of actions is always delimited or selective, because humans cannot act in general or in a vacuum. The essence of action is irremediably conditioned by the social (Dewey, 1938 [1986]). It follows that thinking and ideas or meanings developed through inquiry are social and cultural as well. Thus, a reflected action is created in relation to a specific situation or problem.

The concept of inquiry in pragmatism developed out of the criticism leveled at the concept of knowledge in formal logic with its references to a priori knowledge above and beyond the human world of experience (Dewey, 1929 [1984]). Dewey’s development of logic as a theory of inquiry is based on everyday life experiences. Inquiry cannot be reduced to a response to purely abstract thoughts as it is anchored in situations as part of our everyday life. It is part of life to inquire, turn things around intellectually, come to conclusions, and make evaluations. This is how people learn and become cognizant human beings.

Inquiry is a process that starts with a sense that something is wrong. Intuitively, the inquirer suspects there is a problem. The suspicion does not necessarily arise from an intellectual wit. It is not until the inquirer begins to define and formulate the problem that inquiry moves into an intellectual field by using the human ability to reason and think verbally. In other words, the inquirer uses previous experiences from similar situations. According to Dewey, the inquirer tries to solve the problem by applying different working hypotheses and concludes by testing a solution model. The initial feeling of uncertainty, the uncertainty that started the inquiry process must disappear before a problem has been solved. If the inquiry is to lead to new experiences, to learning, it requires thinking and reflection over the relation between the problem’s definition and formulation and the solution. It is not until deliberation has been applied to establish a relation between the action and the consequence(s) of the action that learning takes place in the sense that it is possible to act more informed in a new and similar situation.

In the understandings of the organization as a system and the organization as communities of practice, the individual is made sub-ordinate to the organization, either by ‘choice,’ that is, to adhere to the organization as a systemic entity, or by dissolving the individual in the communities of practice (see also Casey, 2002). We argue that a theory of the organization in organizational learning based on pragmatism is able to avoid this kind of sub-ordination. To conceptualize an organizational learning theory based on pragmatism, we draw upon the social arenas/worlds theory of Anselm Strauss (Strauss, 1993). Strauss’s concept of organizations understood as arenas consisting of transactional social worlds has the same ontological basis as the COP and the cultural approach to organizations. The social world metaphor is, however, more strongly oriented towards processes of conflicts, negotiation, and tensions within and between social worlds, and the analysis of how these conflicting situations generate the possibility of changing arenas and social worlds (Brandi, 2010; Elkjaer and Hyusman, 2008).

The concept of social worlds originates from early social studies characteristic of the Chicago School of sociology. Firmly rooted in the classical pragmatism of Dewey and symbolic interactionism of Mead, one of its most prominent scholars, Anselm Strauss, developed social arenas/worlds theory as a conceptual frame for understanding the emergence and flow of activities in organizations. Social worlds are defined as:

Groups with shared commitments to certain activities, sharing resources of many kinds to achieve their goals, and building shared ideologies about how to go about their business.

(Clarke, 1991: 131)

In a social worlds perspective there are ‘commitments,’ ‘goals,’ and ‘ideologies’ that ‘belong’ to a group. There are not only patterns of access and participation, although they are also present. In a social worlds understanding, organizations are arenas of coordinated collective actions in which social worlds emerge as a result of commitment to organizational activities. It is the tensions and ruptures between these commitments within and between social worlds that may create avenues for questioning existing practices.

One especially relevant aspect of social worlds theory is that it explicitly focuses on the intersecting and segmentation processes between and within social worlds (Strauss, 1978: 123; 1993: 39). Intersecting looks at the bridging and interpenetrating processes of social worlds where social worlds and their actors engage in collaborative inquiry. Strauss (1982) underlines the significance of organizations characterized as a negotiated order. Negotiation denotes a fundamental trait that illustrates both the dynamic and political characteristics of social worlds. Every social world is characterized by intersections, caused by both internal and external (between social worlds) conflicts and contradictions, which convey negotiations and give rise to segmentation/intersecting processes. These processes create avenues for organizational learning by creating new relations between social worlds and practices within social worlds. Thus, segmentation/intersecting is a highly political process through its dependence on negotiations or processual ordering, as Strauss (1993: 254) later argued. This understanding of organization is a way of grasping the mutual relationship between individual and organization (social worlds) as both encompassing the organizational processes of ordering and the individuals as potential active participants who may or may not engage in the organizational activities.

In sum, pragmatism is a reminder of agency but agency grounded in and part of the shared and non-shared social worlds as well as individual capacities. Inquiry is useful because it can enact new practices by way of working hypotheses, and is necessary in order to produce learning and not only socialization. The organizational members and the organization are weaved together in social worlds in which inquiry and experiencing goes on as a continuous process. In pragmatism, the learning content may be coined as the development of human experience, which at the same time is to come to know about the world and be able to act in the world. Social learning theory for organizational learning inspired by pragmatism does not make a separation between coming to know about practice and coming to be a practitioner. It is not possible to develop experience as either processes of knowledge or processes of being and becoming. Experience and inquiry encompass both processes.

The learning method is inquiry, which includes thinking as a way to define problems, and reflection as a way to move learning outcome into the verbal and conscious arena, which paves the way for change and new practice. Inquiry begins in the senses, the bodily feelings and emotions, which may be turned into words in order to provide a way to learn from inquiry. Thus, inquiry is a way to enact knowledge that does not begin with language and conscious reflection. Inquiry cannot be restricted to mind or bodies, thinking or actions, but encompasses both. And their consequences are not to be restricted to knowledge acquisition but to include development of experience, creation of identity, and becoming a member of social worlds.

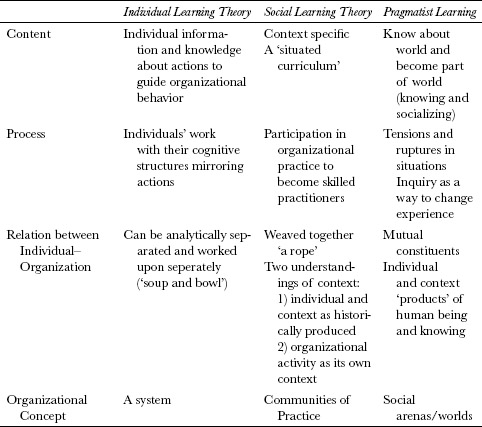

In pragmatism, it is not possible to separate the individual from the social, the context and/or the organization. The two are mutually constituted as human beings and human knowing, and as such they are products of history and culture, encompassed in social worlds theory of organizations. For a summary of the three positions, see Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Summary of the three positions