Personal Knowing, Tacit Knowledge, and Skillful Performance: A Primer in Polanyi

Personal knowing

One of the most distinguishing features of Michael Polanyi’s work is his insistence on overcoming well established dichotomies, such as theoretical versus practical knowledge, sciences versus the humanities or, to put it differently, his determination to show the common structure underlying all kinds of knowledge. Polanyi, a chemist turned philosopher, was categorical that all knowing involves skillful action and that the knower necessarily participates in all acts of understanding. For him the idea that there is such a thing as ‘objective’ knowledge, self-contained, detached, and independent of human action, was wrong and pernicious. ‘All knowing,’ he insists, ‘is personal knowing—participation through indwelling’ (Polanyi and Prosch, 1975: 44; italics in the original).

Take, for example, the use of geographical maps. A map is a symbolic representation of a particular territory. As an explicit representation, a map is, in logical terms, no different from a theoretical system or a system of behavioral rules: they all aim at enabling purposeful human action, that is, respectively, to get from A to B; to predict; and to guide behavior. We may be familiar with a map per se but to use it we need to be able to relate it to the world outside the map. More specifically, to use a map we need to be able to do three things. First, we must identify our current position on the map (‘you are here’). Secondly, we must find our itinerary on the map (‘we want to go to the National Museum, which is over there’). And thirdly, to actually reach our destination, we must identify the itinerary by various landmarks in the landscape around us (‘you go past the train station, and then turn left’). In other words, a map, no matter how elaborate it is, cannot read itself; it requires the judgment of a skilled reader who will relate the map to the world through both cognitive and sensual means (Polanyi and Prosch, 1975: 30; Polanyi, 1962: 18–20).

The same personal judgment is involved whenever abstract representations encounter the world of experience. We are inclined to think, for example, that Newton’s laws can predict the position of a planet circling round the sun, at some future point in time, provided its current position is known. Yet this is not quite the case: Newton’s laws cannot do that, only we can. The difference is crucial. The numbers entering the relevant formulae, from which we compute the future position of a planet, are readings on our instruments—they are not given, but need to be worked out. Similarly, we check the veracity of our predictions by comparing the results of our computations with the readings of the instruments—the predicted computations will rarely coincide with the readings observed and the significance of such a discrepancy needs to be worked out, again, by us (Polanyi, 1962: 19; Polanyi and Prosch, 1975: 30). Notice that, like in the case of map reading, the formulae of celestial mechanics cannot apply themselves; the personal judgment of a human agent is necessarily involved in applying abstract representations to the world.

The general point to be derived from the above examples is this: insofar as a formal representation has a bearing on experience, that is to say the extent to which a representation encounters the world, personal judgment is called upon to make an assessment of the inescapable gap between the representation and the world encountered. Given that the map is a representation of the territory, I need to be able to match my location in the territory with its representation on the map if I am to be successful in reaching my destination. Personal judgment cannot be prescribed by rules but relies essentially on the use of our senses (Polanyi, 1962: 19; 1966: 20; Polanyi and Prosch, 1975: 30). To the extent this happens, the exercise of personal judgment is a skillful performance, involving both the mind and the body.

The crucial role of the body in the act of knowing has been persistently underscored by Polanyi (cf. Gill, 2000: 44–50). As said earlier, the cognitive tools we use do not apply themselves; we apply them and, thus, we need to assess the extent to which our tools match aspects of the world. Insofar as our contact with the world necessarily involves our somatic equipment—‘the trained delicacy of eye, ear, and touch’ (Polanyi and Prosch, 1975: 31)—we are engaged in the art of establishing a correspondence between the explicit formulations of our formal representations (be they maps, scientific laws, or organizational rules) and the actual experience of our senses. As Polanyi (1969: 147) remarks, ‘the way the body participates in the act of perception can be generalized further to include the bodily roots of all knowledge and thought. . . . Parts of our body serve as tools for observing objects outside and for manipulating them’.

Rules, particulars, and tacit knowledge

If we accept that there is, indeed, a ‘personal coefficient’ (Polanyi, 1962: 17) in all acts of knowing, which is manifested in a skillful performance carried out by the knower, what is the structure of such a skill? What is it that enables a map-reader to make competent use of the map to find his or her way around, a scientist to use the formulae of celestial mechanics to predict the next eclipse of the moon, and a physician to read an X-ray picture of a chest? For Polanyi the starting point towards answering this question is to acknowledge that ‘the aim of a skillful performance is achieved by the observance of a set of rules which are not known as such to the person following them’ (Polanyi, 1962: 49). A cyclist, for example, does not normally know the rule that keeps his or her balance, nor does a swimmer know what keeps him or her afloat. Interestingly, such ignorance is hardly detrimental to their effective execution of their respective tasks.

The cyclist keeps his or her balance by winding through a series of curvatures. One can formulate the rule explaining why the cyclist does not fall off the bicycle—‘for a given angle of unbalance the curvature of each winding is inversely proportional to the square of the speed at which the cyclist is proceeding’ (Polanyi, 1962: 50)—but such a rule would hardly be helpful to the cyclist. Why? As we will see below, this is partly because no rule is helpful in guiding action unless it is assimilated and stored in the unconscious mind. It is also partly because there is a host of other particular elements to be taken into account, which are not included in this rule and, crucially, are not—cannot be—known by the cyclist. Skills retain an element of opacity and unspecificity; they cannot be fully accounted for in terms of their particulars, since their practitioners do not ordinarily know what those particulars are; even when they do know them, as for example in the case of topographic anatomy, they do not know how to integrate them (Polanyi, 1962: 88–90). It is one thing to learn a list of bones, arteries, nerves, and viscera and quite another to know how precisely they are intertwined inside the body (Polanyi, 1962: 89).

This is the reason why, contrary to what Collins (2007: 258) argues, ‘somatic-limit knowledge’ cannot ‘be converted into explicit rules.’ Ribeiro and Collins (2007: 1431) define ‘somatic-limit knowledge’ as ‘knowledge that is tacit only because it is so complex that human beings can master it only though socialization—that is guided instruction in a social group’ (Ribeiro and Collins, 2007: 1431). Collins (2007: 259) invites us to join a thought experiment to demonstrate the contingently tacit nature of somatic-limit knowledge. Imagine conditions, he says, in which you could cycle so slowly, as for example would be the case in the lower gravitational field of the Moon, that when you were in danger of falling over, this would happen so slowly as to enable you to read and follow a set of balancing instructions that would allow you to regain your balance. If that were to be the case, the limits of somatic knowledge would be overcome. In certain conditions, somatic-limit knowledge can be turned to explicit knowledge, argues Collins (2007: 258).

However, this does not seem to be a particularly convincing claim. The rules of bike-riding cannot be used by humans when cycling not due to the size of our brains and the speed of our mental operations, as Collins (2007: 258) implies, but because of our embodied involvement in a skillful action. More is going on in bike-riding than is captured by formal rules, although we do not explicitly know what; personal knowledge is ‘logically unspecificable’ (Polanyi, 1962: 56). We cannot logically know the bodily particulars of skillful performance that lapse from our consciousness, since attempting to find out would stop the performance. The price we pay for skillfully carrying out a task is partial ignorance of how we do so. We come to know the particulars in terms of ‘their contribution to a reasonable result’ and, insofar as this is the case, ‘they have never been known and were still less willed in themselves’ (Polanyi, 1962: 63). We are, of course, capable of formulating rules, and as Collins points out, Polanyi himself formulated the rule for bike-riding, but he also pointed out that the reason we cannot ride by following his rule is that ‘there are a number of other factors to be taken into account in practice which are left out in the formulation of this rule’ (Polanyi, 1962: 50).

How, then, do individuals know how to exercise their skills? In a sense they don’t—know how ignorance cannot be eliminated. ‘A mental effort,’ notes Polanyi (1962: 62), ‘has a heuristic effect: it tends to incorporate any available elements of the situation which are helpful for its purpose.’ Any particular elements of the situation which may help the purpose of a mental effort are selected insofar as they contribute to the performance at hand, without the performer knowing them as they would appear in themselves. The particulars are subsidiarily known insofar as they contribute to the action performed. As Polanyi remarks:

this is the usual process of unconscious trial and error by which we feel our way to success and may continue to improve on our success without specifiably knowing how we do it—for we never meet the causes of our success as identifiable things which can be described in terms of classes of which such things are members. This is how you invent a method of swimming without knowing that it consists in regulating your breath in a particular manner, or discover the principle of cycling without realizing that it consists in the adjustment of your momentary direction and velocity, so as to counteract continuously your momentary accidental unbalance.

(Polanyi, 1962: 62, italics in the original)

When engaged in action, we cannot identify the subsidiary particulars that render our action possible. This has nothing to do with the speed of our mental operations, but is an ontological feature of skilled action. Our tacit knowledge of subsidiaries is rather manifested in our patterns of action (Taylor, 1991b: 308; 1995: 68–69).

There are two different kinds of awareness in exercising a skill. When an individual uses a hammer to drive a nail (one of Polanyi’s favorite examples—see Polanyi, 1962: 55; Polanyi and Prosch, 1975: 33), that individual is aware of both the nail and the hammer but in a different way. One watches the effects of his or her strokes on the nail, and tries to hit it as effectively as possible. Driving the nail down is the main object of the person’s attention and they are focally aware of it. At the same time, that individual is also aware of the feeling in the palm of their hand of holding the hammer. But such awareness is subsidiary: the feelings of holding the hammer in the palm are not an object of the hammerer’s attention but an instrument of it. The watching of the action of hitting the nail is caused by being aware of it. As Polanyi and Prosch (1975: 33) remark: ‘I know the feelings in the palm of my hand by relying on them for attending to the hammer hitting the nail. I may say that I have a subsidiary awareness of the feelings in my hand which is merged into my focal awareness of my driving the nail’ (italics in the original).

The structure of tacit knowledge

If the above is accepted, it means that we can be aware of certain things in a way that is quite different from focusing our attention on them. One has a subsidiary awareness of holding the hammer in the act of focusing on hitting the nail. In being subsidiarily aware of holding a hammer the individual sees it as having a meaning that is wiped out if that person focuses attention on how they are holding the hammer. Subsidiary awareness and focal awareness are mutually exclusive (Polanyi, 1962: 56). If we switch our focal attention to particulars of which we had only subsidiary awareness before, their meaning is lost and the corresponding action becomes clumsy. If a pianist shifts his or her attention from the piece being played to how his or her fingers are moving; if a speaker focuses his or her attention on the grammar being used instead of the act of speaking; or if a carpenter shifts his or her attention from hitting the nail to holding the hammer, they will all be confused. We must rely (to be precise, we must learn to rely) subsidiarily on particulars for attending to something else, hence our knowledge of them remains tacit (Polanyi, 1966: 10; Winograd and Flores, 1987: 32). In the context of carrying out a specific task, we come to know a set of particulars without being able to identify them. In Polanyi’s (1966: 4) memorable phrase, ‘we can know more than we can tell.’

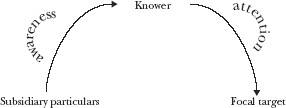

From Figure 21.1 it follows that tacit knowledge forms a triangle, at the three corners of which are the subsidiary particulars, the focal target, and the knower who links the two. It should be clear from the above that the linking of the particulars to the focal target does not happen automatically but is a result of the act of the knower. It is in this sense that Polanyi talks about all knowledge being personal and all knowing being action. No knowledge is possible without the integration of the subsidiaries to the focal target by a person. However, unlike explicit inference, such integration is essentially tacit and irreversible. Its tacitness was earlier discussed; its irreversible character can be seen if juxtaposed to explicit (especially deductive) inference, whereby one can unproblematically traverse between the premises and the conclusions. Such traversing is not possible with tacit integration: once an individual has learned to play the piano they cannot go back to being ignorant of how to do it. While pianists can certainly focus their attention on how they move their fingers, thus making the performance clumsy to the point of paralyzing it, the musician can always recover their ability by casting their mind forward to the music itself.

Figure 21.1 Personal Knowledge

With explicit inference, no such break-up and recovery are possible (Polanyi and Prosch, 1975: 39–42). When, for example, examining a legal syllogism or a mathematical proof an individual proceeds orderly from the premises, or a sequence of logical steps, to the conclusions. Nothing is lost and nothing is recovered—there is complete reversibility. The mathematician can go back to check the veracity of each constituent statement separately and how it logically links with its adjacent statements. Such reversibility is not, however, possible with tacit integration. Shifting attention to subsidiary particulars entails the loss of the skillful engagement with the activity at hand. By focusing on a subsidiary constituent of skilful action one changes the character of the activity one is involved with. There is no reversibility in this instance.

The structure of tacit knowing has three aspects: the functional, the phenomenal, and the semantic. The functional aspect consists in the from–to relation of particulars (or subsidiaries) to the focal target. Tacit knowing is from–to knowing: we humans know the particulars by relying on our awareness of them for attending to something else. Human awareness has a ‘vectorial’ character (Polanyi, 1969: 182): it moves from subsidiary particulars to the focal target (cf. Gill, 2000: 38–39). Or, in the words of Polanyi and Prosch (1975: 37–38), ‘subsidiaries exist as such by bearing on the focus to which we are attending from them’ (italics in the original). The phenomenal aspect involves the transformation of subsidiary experience into a new sensory experience. The latter appears through—it is created out of—the tacit integration of subsidiary sense perceptions. Finally, the semantic aspect is the meaning of subsidiaries, which is the focal target on which they bear (See Table 1).

Table 1 The three-dimensional structure of tacit knowing

|

The aspects of tacit knowing in Table 1 will become clearer with an example. Imagine a dentist exploring a tooth cavity with a probe. The exploration has a functional aspect: the dentist relies subsidiarily on his or her feeling of holding the probe in order to attend focally to the tip of the probe exploring the cavity. In doing so, the sensation of the probe pressing on the dentist’s fingers is lost and, instead, he or she feels the point of the probe as it touches the cavity. This is the phenomenal aspect, whereby a new coherent sensory quality appears (i.e. the dentist’s sense of the cavity) from the initial sense perceptions (i.e. the impact of the probe on the fingers). Finally, the probing has a semantic aspect: the dentist gets information by using the probe. That information is the meaning of his or her tactile experiences with the probe. As Polanyi (1966:13) notes, the dentist becomes aware of the feelings in his or her hand in terms of their meaning located at the tip of the probe, which is being attended to.

We engage in tacit knowing through virtually anything we do: we are normally unaware of the movement of our eye muscles when we observe, of the rules of language when we speak, of our bodily functions as we move around. Indeed, to a large extent, our daily life consists of a huge number of small details of which we tend to be focally unaware. When, however, we engage in more complex tasks, requiring even a modicum of specialized knowledge, then we face the challenge of how to assimilate the new knowledge—to interiorize it, dwell in it—in order to get things done efficiently and effectively. Polanyi gives the example of a medical student attending a course in X-ray diagnosis of pulmonary diseases. The student is initially puzzled: ‘he can see in the X-ray picture of a chest only the shadows of the heart and the ribs, with a few spidery blotches between them. The experts seem to be romancing about figments of their imagination; he can see nothing that they are talking about’ (Polanyi, 1962: 101).

At the early stage of training the student has not assimilated the relevant knowledge; unlike the dentist with the probe, the student cannot yet use it as a tool to carry out a diagnosis. The student, at this stage, is a remove from the diagnostic task as such: cannot think about it directly; the student rather needs to think about the relevant radiological knowledge first. If training is persevered with, however, ‘he will gradually forget about the ribs and begin to see the lungs. And eventually, if he perseveres intelligently, a rich panorama of significant details will be revealed to him: of physiological variations and pathological changes, of scars, of chronic infections and signs of acute disease. He has entered a new world’ (Polanyi, 1962: 101).

This is a useful illustration of the structure of tacit knowledge. The student has now interiorized the new radiological knowledge; the latter has become tacit knowledge, of which the student is subsidiarily aware while attending to the X-ray itself. Radiological knowledge exists now not as something unfamiliar, which needs to be learned and assimilated before a diagnosis can take place, but as a set of particulars—subsidiaries—which exist as such by bearing on the X-ray (the focus) to which the student is attending from them. Insofar as this happens, a phenomenal transformation has taken place: the heart, the ribs, and the spidery blotches gradually disappear and, instead, a new sensory experience appears—the X-ray is no longer a collection of fragmented radiological images of bodily organs, but a representation of a chest full of meaningful connections. Thus, as well as having functional and phenomenal aspects, tacit knowledge has an important semantic aspect: the X-ray conveys information to an appropriately skilled observer. The meaning of the radiological knowledge, subsidiarily known and drawn upon by the student, is the diagnostic information received from the X-ray: it tells the student what it is that is being observed by using that knowledge.

It should be clear from the above that, for Polanyi, there is no difference between tangible (artifactual) things like probes, sticks, or hammers on the one hand, and intangible (symbolic) constructions such as radiological, linguistic, or cultural knowledge on the other—they are all tools enabling a skilled user to get things done. To use a tool properly we need to assimilate it and dwell in it. In Polanyi’s (1969: 148) words, ‘we may say that when we learn to use language, or a probe, or a tool, and thus make ourselves aware of these things as we are our body, we interiorize these things and make ourselves dwell in them’ (italics in the original). The notion of indwelling, strongly reminiscent of a Heideggerian vocabulary (Dreyfus, 1991; Winograd and Flores, 1987; Spinosa et al., 1997), is crucial for Polanyi and turns up several times in his writings. It is only when we dwell on the tools we use, make them extensions of our own body, that we amplify the powers of our body and shift outwards the points at which we make contact with the world outside (Polanyi, 1962: 59, 1969: 148; Polanyi and Prosch, 1975: 37). Otherwise, our use of tools will be clumsy and will hinder getting things done.

We interiorize tools (artifactual and symbolic alike) when we are socialized into a socio-material practice (Benner, Hooper-Kyriakidis, and Stannard, 1999: 30–47; Polanyi, 1962: 101). For example, Gawande (2002), a surgical resident at a Boston hospital, gives a vivid account of his socialization in medical practice. Through dealing with particular incidents of patients, initially under the supervision of, and later in collaboration with, more experienced members of his practice, the trainee surgeon was learning to use the key categories implicated in a surgeon’s job. Through his participation in this practice he was gradually learning to relate to his circumstances ‘spontaneously’ (Wittgenstein, 1980: 699), that is to say, ‘uncritically’ (Polanyi, 1962: 60): to use medical equipment, to recognize certain symptoms, to relate to colleagues and patients. The needles and how to use them in patients’ chests, the X-rays and how to read them, and his relationships to others were not focal objects of thought for him, but subsidiary particulars—taken-for-granted aspects of the normal setting in all its recognizable stability and regularity.

The ‘spontaneous’ aspects of the activities practitioners undertake are primary and constitute what Wittgenstein (1979: 94) calls the ‘inherited background,’ against which practitioners make sense of their particular tasks (Shotter and Katz, 1996: 225; Taylor, 1993a: 325, 1995: 69). Practitioners are aware of the background but their awareness is largely ‘inarticulate’ (Taylor, 1991: 308) and implicit in their activity (Ryle, 1963: 40–41). The background provides the frame that renders their explicit representations comprehensible (Dreyfus, 1991: 102–4; Taylor, 1993a: 327–328; 1995: 69–70). As Wittgenstein (1979: 473–479) aptly noted, the basis of a socio-material practice is activity, not knowledge; practice, not thinking; certainty, not uncertainty. With the help of more experienced others we first learn to act, that is to accept the certainties of our particular socio-material practice (e.g. to use needles, to recognize the symptoms of pulmonary disease, to relate to patients) and, thus, relate spontaneously to our surroundings, and later we reflect on them. Experience comes first, reflection later.

Thus, in Gawande’s case, the trainee surgeon was not training his mind alone, but also his hands and his whole body (how to interact with patients; the sort of footing he should be on with senior others). He may not have had descriptive terms for that embodied understanding—the manual dexterity he was developing with regard to feeling the human skin, for example. His embodied understanding was rather manifested in patterns of appropriate action, namely action that conformed to a sense of what was right. More generally, as Taylor (1991: 309) notes, agents’ actions are responsive to this sense of rightness, although the ‘norms’ underlying their actions may be unformulated or in a fragmentary state.

The interiorization of a tool—its instrumentalization in the service of a purpose—is beneficial to users for it enables them to acquire new experiences and carry out more competently the task at hand (Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 2000). Compare, for example, one who learns driving a car to one who is an accomplished driver. The former may have learned how to change gear and to use the brake and the accelerator but cannot, yet, integrate those individual skills—the learner driver has not constructed a coherent perception of driving, the phenomenal transformation has not taken place yet. At the early stage, the driver is conscious of what needs to be done and feels the impact of the pedals on his or her foot and the gear stick on his or her palm; the driver has not learned to unconsciously correlate the performance of the car with the specific bodily actions he or she undertakes as a driver. The experienced driver, by contrast, is unconscious of the actions by which he or she drives—car instruments are tools whose use has been mastered, that is interiorized, and the experienced driver is therefore able to use them for the purpose of driving (Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 2000). By becoming unconscious of certain actions, the experienced driver expands the domain of experiences he or she can concentrate on as a driver (i.e. principally road conditions and other drivers’ behavior).

The more general point to be derived from the preceding examples is formulated by Polanyi (1962: 61) as follows:

we may say . . . that by the effort by which I concentrate on my chosen plane of operation I succeed in absorbing all the elements of the situation of which I might otherwise be aware in themselves, so that I become aware of them now in terms of the operational results achieved through their use.

This is important because we get things done, we achieve competence, by becoming unaware of how we do so. Of course one can take an interest in, and learn a great deal about, the gearbox and the acceleration mechanism but, to be able to drive, such knowledge needs to lapse into unconsciousness.

This lapse into unconsciousness . . . is accompanied by a newly acquired consciousness of the experiences in question, on the operational plane. It is misleading, therefore, to describe this as the mere result of repetition; it is a structural change achieved by a repeated mental effort aiming at the instrumentalization of certain things and actions in the service of some purpose.

Polanyi (1962: 62)

Notice that, for Polanyi, the shrinking of consciousness of certain things is, in the context of action, necessarily connected with the expansion of consciousness of other things. Particulars such as ‘changing gear’ and ‘pressing the accelerator’ are subsidiarily known, as the driver concentrates on the act of driving. Knowing something, then, is always a contextual issue and fundamentally connected to action (the ‘operational plane’). My knowledge of gears is in the context of driving, and it is only in such a context that I am subsidiarily aware of that knowledge. If, however, I were a car mechanic, gears would constitute my focus of attention, rather than being an assimilated particular. Knowledge has a recursive form: given a certain context, we black-box—assimilate, interiorize, instrumentalize—certain things in order to concentrate—focus—on others. In another context, and at another level of analysis (cf. Bateson, 1979: 43), we can open up some of the previously black-boxed issues and focus our attention on them. In theory this is an endless process, although in practice there are institutional and practical limits to it.

In this way we can to some extent ‘vertically integrate’ our knowledge, although, as said earlier, what pieces of knowledge we use depends, at any point in time, on context. If the driver happens to be a car mechanic as well as an engineer he or she will have acquired three different bodies of knowledge, each having a different degree of abstraction, which, taken together, give his or her knowledge depth and make him or her a sophisticated driver (cf. Harper, 1987: 33). How, however, the driver draws on each one of them—that is, what is focally and what is subsidiarily known—depends on the context-in-use.

Moreover, each one of these bodies of knowledge stands on its own, and cannot be reduced to any of the others. The practical knowledge a driver has of their car cannot be replaced by the theoretical knowledge of an engineer; the practical knowledge an individual has of their own body cannot be replaced by the theoretical knowledge of a physician (cf. Polanyi, 1966: 20). In the social world, specialist, abstract, theoretical knowledge is necessarily refracted through the ‘life world’—the taken-for-granted assumptions by means of which human beings organize their experience, knowledge, and transactions with the world (cf. Bruner, 1990: 35).