Hand-Holding: The First Retailers

We didn’t want to sell Altairs. We wanted to solve problems.

–Dick Heiser, computer retailer

The first personal-computer store appeared not long after the Altair announcement. Its origin had very little to do with the usual motives or starting a retail business.

The First Personal-Computer Store

On June 15, 1975, 125 hobbyists and computer novices gathered in the recreation room of the Laurel Tree Apartments in Miraleste, California. Digital engineer Don Tarbell and computer neophyte Judge Pearce Young had brought them together to form the Southern California Computer Society. The participants engaged in a lively debate over the structure and purpose of the club. At one point, someone asked for a showing of hands of those who either owned or had ordered an Altair. A forest of hands popped up from the crowd.

Dick Heiser, a systems analyst who was among the assembled, was struck by the response. He realized that these Altair customers were going to have a lot of questions about assembling their kits. He thought that maybe he could be of help. Heiser had recently spent $14,000 building a video word processor for a low-cost minicomputer. With the introduction of the Altair, he realized that he could write a similar program for it for about $4,000. He was familiar with the innards of a computer and was eager to work on an Altair.

Heiser then had a brainstorm: why not set up a small storefront to market the Altair kits and provide advice and support for buyers? Heiser had little business experience and never imagined working as a salesman, but he knew that he’d have fun putting his technical skills to use. He wondered whether it could be profitable. He sat down and devised a cash-flow plan. If he paid $200 in rent per month and sold around 10 to 20 assembled computers at $439 each, he could stay in the black. It seemed to be worth a try.

In June 1975, Heiser flew to Albuquerque to talk to the people at MITS. The MITS execs weren’t sure what to make of Dick Heiser. Ed Roberts thought he was a “nice guy” but lacked the aggressiveness that marked a born entrepreneur. Roberts also worried about Heiser’s profit margin. MITS was selling the Altair kits for $395 ($439 assembled), which left skimpy profits. MITS couldn’t afford to discount its prices for anyone. Roberts hadn’t built any room for discounts into the Altair’s asking price. Heiser could buy the kits, assemble them, and sell them at the assembled price, for a pitiful 10 percent margin. Despite all this, Roberts took Heiser seriously. Others had approached MITS with the retailing idea, but Heiser was the first to come with a spreadsheet. “They thought I was a little weird,” Heiser recalled, “but they told me it sounded like a good idea, and we signed a contract.”

Heiser leased a small space for $225 a month in a low-rent area of West Los Angeles and launched the world’s first computer store. In mid-July, he opened for business. In large letters across the front of his store he advertised the outlet’s official name, Arrow Head Computer Company. In smaller letters, below the name, he added the tag line “The Computer Store” because he thought it sounded “funky” and interesting. Soon everyone was calling the outlet The Computer Store.

It was a strange kind of store. Heiser, an imposing figure with his beard and cowboy hat, would be engaged in a serious technical discussion with a hobbyist one minute, and the next minute be assuring a skeptic that the Altair, despite its low price, was truly a computer. When not attending to customers, he’d hole up in the back room where he repaired equipment and worked on his own computer, which he was still in the process of soldering together.

Heiser quickly discovered that his spreadsheet was seriously in error. He had anticipated getting a small but steady stream of individual computer purchases at $439 each, the price of an assembled Altair. Instead, he found that someone who was buying a computer could easily spend another $4,000 on accessories—extra memory, video terminals, disk drives, and such. It was his first small excursion into retailing and Heiser was amazed that so many people were willing to spend real money on these machines. In his first month, he took in between $5,000 and $10,000, and in his first five months in excess of $100,000. By the end of 1975, he was ringing up more than $30,000 in sales per month.

Heiser did little advertising other than posting flyers at large engineering firms such as System Development Corporation, Rand, and TRW. As a result, most of his early customers were engineers, who were typically computer enthusiasts who had moved to California to work in high technology. This being Southern California, he also got his share of celebrities: Herbie Hancock, Bob Newhart, and Carl Sagan visited The Computer Store. But the clientele consisted mainly of hobbyists.

Heiser’s Challenges

A customer base consisting exclusively of hobbyists was probably just as well, because the process of assembling an Altair generated each and every problem Heiser anticipated. “It was really tough in those days,” he recalled. “You had to know electronics as well as software. You had to bring up the raw machine, and you had to use the toggle switches to put in the bootstrap loader,” he said, describing the various steps required to get an Altair up and working. Buyers who stumbled at various points en route to setting up their Altairs came running back to Heiser, who patiently instructed them about careful assembly, repaired any malfunctions, and lent a sympathetic ear to complaints about the MITS memory boards.

Although Heiser was selling enough computers to make a healthy profit, a careful accounting of his and his employees’ time would have shown that most of their time was spent explaining the technology, repairing machines, setting up systems, and reassuring customers. Hand-holding, community building, proselytizing. It worked, but it sure wasn’t the business-school model of retail sales.

The Computer Store was not without some local competition. In late November 1975, John French opened his Computer Mart in a small rented office suite. French offered the IMSAI, which was simply a better piece of computer hardware than the Altair. On the other hand, Heiser, with Gates and Allen’s BASIC computer language, had the superior software offering. Software was the more important ingredient of the two, but because BASIC could run on French’s machines, French thrived along with Heiser. Eventually, French sold his interest in Computer Mart and invested in his friend Dick Wilcox’s computer company Alpha Micro.

Heiser also faced competition from a group of devout Indian Sikhs in Pasadena. Although American by birth and upbringing, they embraced the culture of their Indian ancestors. They also embraced cutting-edge technology. “For them, it wasn’t, ‘Let’s sit by the river and meditate,’” Heiser observed. Dressed in their turbans and white coats, the Sikhs sold computers manufactured by Processor Technology, and later sold Apple products. Heiser respected them immensely. Like him, they cared more about solving a customer’s problems than moving more inventory.

In May 1976, Heiser moved The Computer Store to Santa Monica to a facility four times the size of the one in West Los Angeles. He now had several employees and was making $50,000 to $60,000 a month. He installed carpets and desks that made the store look like the offices of a bank executive. Customers would sit across the desk from a salesperson to discuss system requirements and how best to meet them. Heiser saw himself as more of a counselor than an entrepreneur. The problem-solving approach also gave him personal satisfaction. “I’m a computer enthusiast and a compulsive explainer,” he said.

One problem that he simply couldn’t solve nagged at Heiser. MITS was pressuring him into making questionable deals with his customers. MITS bound the purchase of Gates and Allen’s BASIC to the purchase of the notoriously defective MITS memory boards. Heiser understood the value of the BASIC, but he realized that no one wanted to buy memory boards that didn’t work and he simply didn’t want to carry them.

“We went through a lot of grief trying to make a viable computer system and a viable computer business when we didn’t have any memory devices,” he said. Then MITS decreed that Altair outlets would sell only its products and no one else’s. MITS was worried that if its retailers also offered competitors’ wares, customers would buy the MITS software but reject its hardware. As it turned out, the company’s worries were unfounded given that most of the early computer stores quickly sold out of whatever they got their hands on. Heiser complained to Ed Roberts, but Roberts was adamant and, according to Heiser, threatened to shut down dealers who disobeyed his edict. This policy of exclusivity cost MITS many dealers, but Heiser remained loyal and reluctantly abided by the rules until Roberts sold MITS to Pertec.

Heiser concluded that if MITS was out of touch, Pertec must be roaming the ether. Thinking it could inject MITS with much-needed capital and a proper business orientation, Pertec called a meeting of MITS’s 40 dealers. Heiser listened to the Pertec representatives’ marketing ideas but didn’t think much of them. Pertec figured that if it could sell one computer to General Motors, for instance, the automotive giant would return to Pertec for its next 600 computers. Retailers would soon be filling 600-item orders left and right. The company would rocket into the Fortune 500.

Heiser was amazed at Pertec’s naivete. It was clear to him that the company was oblivious to the problems it had acquired with MITS. At the end of the meeting, Heiser stood up and said that Pertec would have to deal with the immediate problems if it ever hoped to succeed financially with MITS. At that point, Heiser began making plans to go his own way and started stocking other computers, including the Apple II and the PET.

Dick Heiser watched the computer retailing scene change dramatically over the coming years. Discounters entered the market. They employed salespeople with no technical backgrounds who sold machines “with the staples still in the box,” Heiser said. “They may as well have been selling canned peaches.” It was becoming increasingly difficult for Heiser to maintain his standards of excellence. In March 1982, he left the store for good.

Like many of the personal-computer pioneers, Heiser had broken new ground through his unflagging enthusiasm for the technology. Even in retailing, the hobbyist ideal led the way. But unlike computer design, which can be done for love or for money, retailing is necessarily a commercial venture. Computer retailing quickly attracted individuals more aggressive than Heiser, including Paul Terrell.

Byte Shop

Paul Terrell’s friends warned him that retailing computers would never work. Some people, Terrell mused, also said it never snowed in Silicon Valley. Terrell recalled his friends’ warnings as he watched snow drifting down on December 8, 1975—the day he opened his Mountain View Altair dealership, Byte Shop, in the heart of Silicon Valley. Like all the other Altair dealers, Terrell soon ran headlong into the MITS exclusivity policy, except that Terrell chose to ignore it. He was selling all the Altairs he could get, between 10 and 50 a month, plus anything else he could get from IMSAI and Proc Tech. The MITS edict, Terrell concluded, was not only pointless but, if he followed it, financially harmful as well.

Figure 51. Byte Shop The original Mountain View Byte Shop (Courtesy of Paul Terrell)

It wasn’t long before David Bunnell, then MITS vice president of marketing, called to cancel Byte Shop’s Altair dealership. Terrell argued that MITS should regard Byte Shop as something like a stereo store that carried many different brands and could turn a profit for them all. Bunnell waffled. It was Roberts’s decision, he said. At the World Altair Computer Convention in March 1976, Terrell approached Roberts directly about his being dropped from the roster of MITS dealers. Roberts stood firm. Terrell was out.

Figure 52. Inside Byte Shop Paul Terrell opened Byte Shop in 1975 in Mountain View, CA. (Courtesy of Paul Terrell)

At the time, Terrell was selling twice as many IMSAIs as Altairs, and he consoled himself with the fact that MITS’s policy of excommunicating the unfaithful would ultimately hurt Roberts more than his dealers. Terrell was still selling whatever he could stock. As Terrell saw it, he and John French, Dick Heiser’s Computer Mart competitor in Orange County, were responsible for most of IMSAI’s early business. They used to do battle for the product. Terrell would rent a van and drive to the loading dock at IMSAI’s manufacturing site in Hayward to collect his and French’s orders. Check in hand, Terrell would ask, “You want cash on the barrelhead, boys?” It was hardware war.

Terrell had opened Byte Shop in December 1975. By January, people who wanted to open their own stores were approaching him. He signed dealership agreements with them in which he would take a percentage of their profits in exchange for the name and business guidance. Other Byte Shops soon appeared in Santa Clara, San Jose, Palo Alto, and Portland. In March 1976, Terrell incorporated as Byte, Inc.

Terrell was part of the hobbyist community. He named his store after the leading hobbyist magazine, and he insisted that Byte Shop managers in the Northern California area attend meetings of the Homebrew Computer Club.

A single Homebrew meeting might have a half-dozen Byte Shop managers in attendance. “If I had a store manager that didn’t attend the club meetings, he wasn’t going to be my store manager for long. It was that important,” Terrell said. At one Homebrew meeting, a longhaired youth approached him and asked Terrell if he might be interested in a computer that a friend named Steve Wozniak had designed while working out of a garage. Steve Jobs was trying to convince Terrell to carry the Apple I. Terrell told Steve Jobs he had a deal.

Terrell discovered, as Dick Heiser had before him, that customers needed help assembling the machines and obtaining the proper accessories. He got the idea to offer his customers “kit insurance.” For an extra $50, he would guarantee to solve any problems that arose in the course of putting the computers together. Terrell understood that he was doing true specialty retailing and so he had to provide essential information and a certain amount of hand-holding. Terrell likened computer stores to the stereo stores of a decade or two earlier, when clerks routinely had to explain woofers, tweeters, and watts of power to puzzled customers.

Byte Shop’s cachet soared after the July 1976 issue of Business Week described the chain of stores and suggested that it offered significant opportunity to investors. “We had something like five thousand inquiries come in,” Terrell said. He found himself talking to people such as the president of the Federal Reserve Bank. The chairman of Telex Corporation called to ask if Oklahoma was available for franchising. “The credentials [of the callers] were staggering,” Terrell said.

The chain was adding eight stores a month, and Terrell had negotiated a price for an 8080 chip below what IBM was paying. (IBM was not yet building a microcomputer.) By the time Terrell sold Byte Shop operation in November 1977, he had 74 stores operating in 15 states and Japan. He valued the chain at $4 million.

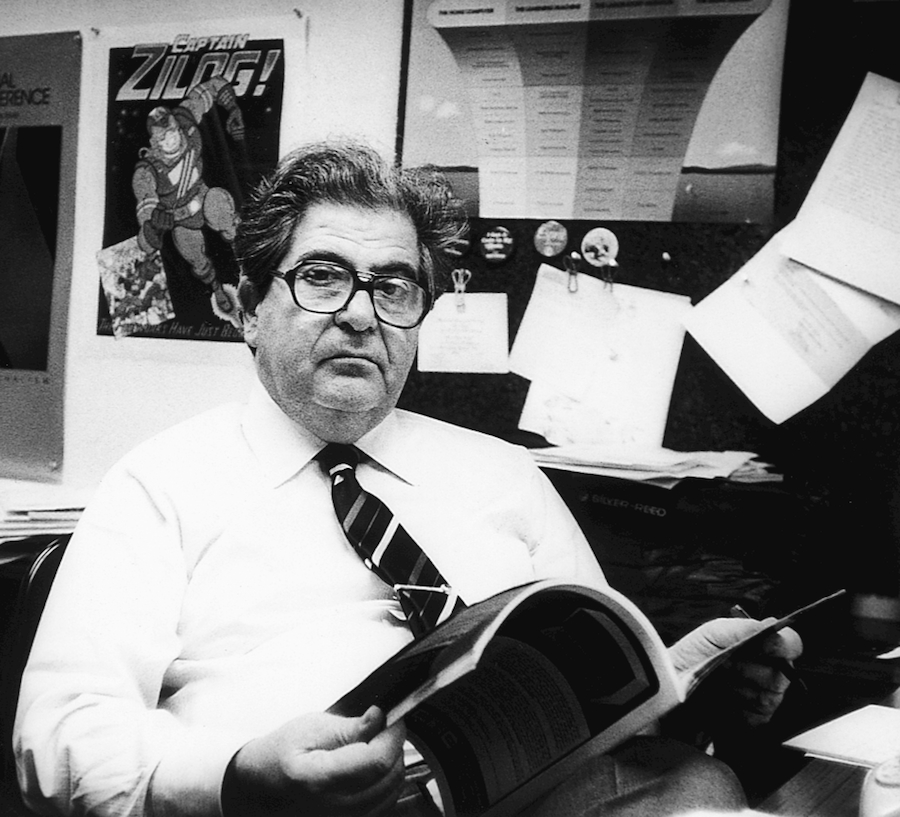

Figure 53. Stan Veit Veit founded Computer Mart in New York, one of the first computer stores.

(Courtesy of Paul Freiberger)

Other computer stores were popping up in many parts of the country, many starting out as Altair dealers then defecting to carry other brands. Dick Brown opened a shop also called The Computer Store on Route 128 in Burlington, Massachusetts. On Long Island, Stan Veit didn’t like the MITS deal from the start and launched his store selling anything he could get his hands on.

In the Midwest, Ray Borrill opened Data Domain in early 1976, with the aim of “out-Terrelling” Paul Terrell. Borrill quickly spun off nearly a dozen affiliated stores from his first outlet in Bloomington, Indiana. He also helped start the Chicago-based Itty-Bitty Machine Company, an ill-fated venture that was conceived during conversations with Ted Nelson at the World Altair Computer Convention.

With computer stores opening across the country, countertop sales had clearly started to elbow aside mail order. At computer-club meetings, Terrell reminded the assembled over and over again, “You don’t have to buy through mail order any more.” Relief from the potential hazards of buying through mail order was one of the best selling points the new retailers could offer.

While running Byte Shop, Terrell began marketing his own brand of computer. Called the Byte 8, it was a private-label product with a profit margin close to 50 percent, twice the average retailer’s 25 percent margin. It proved to be an easy commercial success. “All of a sudden, I realized the power of distribution that Tandy/Radio Shack had. Guaranteed sales.” Tandy, a huge electronics distributor, much bigger than Terrell’s chain, had not yet ventured into computers, although some microcomputer retailers feared Tandy in the way that microcomputer makers feared Texas Instruments. Neither group had cause to worry—for the moment.

Franchising

IMSAI was a manufacturing company run by a sales force. The San Leandro, California, manufacturer of the 80 Micro computer cared little if its products featured the latest technological breakthroughs. IMSAI thrived for a time on its vigorous sales effort and ultimately failed through sheer neglect of its production and customer-service side. It is fitting that IMSAI’s most lasting contribution to the personal-computer field was a sales enterprise—a chain of retail stores, a computer franchise—ComputerLand, started by Ed Faber in 1976.

Faber was an old hand at start-up operations. In 1957, he joined IBM as a sales representative. In 1966, IBM tapped Faber to help develop a department called New Business Marketing, which was designed to ease IBM into the small-business area. Faber helped create a business plan that would include a newly assembled sales force and a fresh marketing concept for the company. This was his first start-up operation, and he relished the challenge. He identified problems, devised solutions for them, and then, as corporate start-up strategies inevitably go, he had to deal with a set of new problems created by the solutions. By 1967, Faber decided he wanted his career to revolve around start-ups, an unusual choice at IBM at the time.

In 1969, after 12 years with IBM, Faber left to join Memorex. At Memorex, and later at a minicomputer company, Faber was hired to build the internal marketing organization. A pattern was developing. After he had created and launched a program, he wanted to move on.

In 1975, Bill Millard invited Faber to join him at start-up IMSAI. Millard described the IMSAI opportunity in lavish terms, which Faber automatically suspected was overstatement. The idea of selling kit computers through the mail for buyers to assemble at home seemed preposterous to Faber, the IBM man. But Faber couldn’t argue with the market’s response to kit computers. IMSAI was knee-deep in orders. At the end of December 1975, he joined IMSAI as its director of sales.

Almost immediately, Faber was in contact with John French, Dick Heiser’s competitor in Southern California. French had approached IMSAI with the idea of buying kits in quantity and retailing them through a computer store. Again, Faber was dumbfounded. Sell computers to customers right off the street? The idea was ludicrous, he thought. On the other hand, Heiser’s retail operation was more than solvent, and IMSAI had little to lose. Faber sold French 10 computer kits at a 10 percent discount, not much for a retailer to work with. French quickly moved the 10 units out the door and was asking for another 15. More orders followed. Other retailers were contacting Faber seeking similar deals. By March 1976, IMSAI had raised its price in order to give retailers a 25 percent margin.

Faber had an excellent reason for courting the dealers. Selling computers to retailers in batches of 10 or 15 was much easier than selling single units to individuals over the telephone. Furthermore, the retail market was wide open. The MITS exclusivity policy was forcing dealers over to IMSAI. Not only were Altair dealers required to carry the MITS line and nothing else, but late arrivals were geographically subservient to early ones, who had established “territory.” Enterprising dealers such as Paul Terrell chafed at the restrictions and ended up bolting to freedom.

The MITS retailing strategy amazed Faber. Ed Roberts sought to dominate his dealers and compel their loyalty. Given the entrepreneurial spirit of the time, Faber predicted that dealers would eventually balk at attempts to control them, and Roberts’s marketing tactics would backfire on him. Defiantly, Faber took a stance in complete opposition to Roberts’s. He encouraged nonexclusivity in the kinds of products dealers could sell, and the freedom to open outlets wherever they pleased. If two dealers wanted to open stores a block away from each other, it was fine with Faber if they competed for sales. IMSAI products would vie with any others on the dealers’ shelves.

By the end of June 1976, some 235 independent stores in the United States and Canada were carrying IMSAI products.

Faber kept an eye on the competing dealers, making note of their relative strengths and weaknesses. Most of them, he realized, were hobbyists with scant experience running a business. Their inexperience was reason enough to fail, he thought; however, they weren’t failing. They were buying more and more merchandise from IMSAI and selling it almost as soon as it came in. In addition, the number of retailers was growing steadily.

Bill Millard got together with Ed Faber to discuss the phenomenon. They wondered what would happen if someone with a well-recognized name started providing comprehensive services, including product purchasing, continuing education, and accounting systems for a network of small, retail storeowners. They were both thinking franchise. They couldn’t find one reason not to start a franchise operation. Faber talked to John Martin, a former associate of Dick Brown’s who was knowledgeable about that kind of business, and Faber attended a seminar on franchising offered through Pepperdine University. When Faber sat down with Millard to talk about launching the operation, Millard asked Faber what he would choose to do. Faber sensed the est in this question and replied that he wanted to be in charge of the franchising operation.

ComputerLand incorporated on September 21, 1976, with Faber as president and Millard as board chairman, and opened its pilot store in Hayward, California, on November 10 of that year. This store served not only as a retail outlet, but also as a training facility for franchise owners. Gordon French, who had helped start the Homebrew Computer Club, worked for ComputerLand early on, helping to evaluate products and establish the pilot store before moving on to do consulting work. ComputerLand eventually sold the flagship outlet and became a pure franchise operation owning no stores at all. The first ComputerLand franchise store opened on February 18, 1977, in Morristown, New Jersey. The second store appeared soon thereafter in West Los Angeles. The stores initially offered products manufactured by IMSAI, Proc Tech, PolyMorphic, Southwest Tech, and Cromemco, the last being one of the first manufacturers to support the new enterprise. Cromemco’s Roger Melen and Harry Garland told Faber they thought the franchise was a terrific idea and gave him one of the best discounts then available.

ComputerLand went on to achieve spectacular success as the nation’s largest chain of computer stores. At the close of 1977, it had 24 stores; by June 1983, 458 ComputerLand stores were operating. ComputerLand outdistanced the Byte Shop chain, and its fiercely competitive practices helped bury the Data Domain chain in the Midwest. In the early 1980s, Faber could reasonably claim that, as far as the general public was concerned, the place to buy computers was ComputerLand.

In 1982, the chain launched plans for a string of software stores called ComputerLand Satellites. ComputerLand intended to license the new software stores to existing franchise owners in its chain. By 1983, Ed Faber conceived a five-year plan that had him semiretired and living in some bucolic setting. He loved to fish and hunt game fowl and was looking forward to a little relaxation. But for the moment, he was busy squelching the competition. To spur the performance of his franchise, whenever he could he opened a ComputerLand outlet near a store belonging to his biggest rival, the new Radio Shack Computer Centers chain.