The Rise of General Software Companies

My unemployment had run out.

–Alan Cooper, software designer, on why he started a software company

After helping Gordon Eubanks write CBASIC, Alan Cooper and Keith Parsons set out to achieve their personal dream of making $50,000 a year. The two had known each other since high school. Parsons was the person who taught Cooper how to tie a necktie, a skill Cooper shelved at college when he became a self-described “long-haired hippie.” Cooper intensely wanted to “get into computers,” and asked the older Parsons for advice. “You’re overtrained,” Parsons told him. “Drop out of school. Get a job.” Cooper took the advice. After work, he and Parsons would get together and talk about starting their own company. Nirvana, they thought, is $50,000 a year.

The Checks Started Rolling In

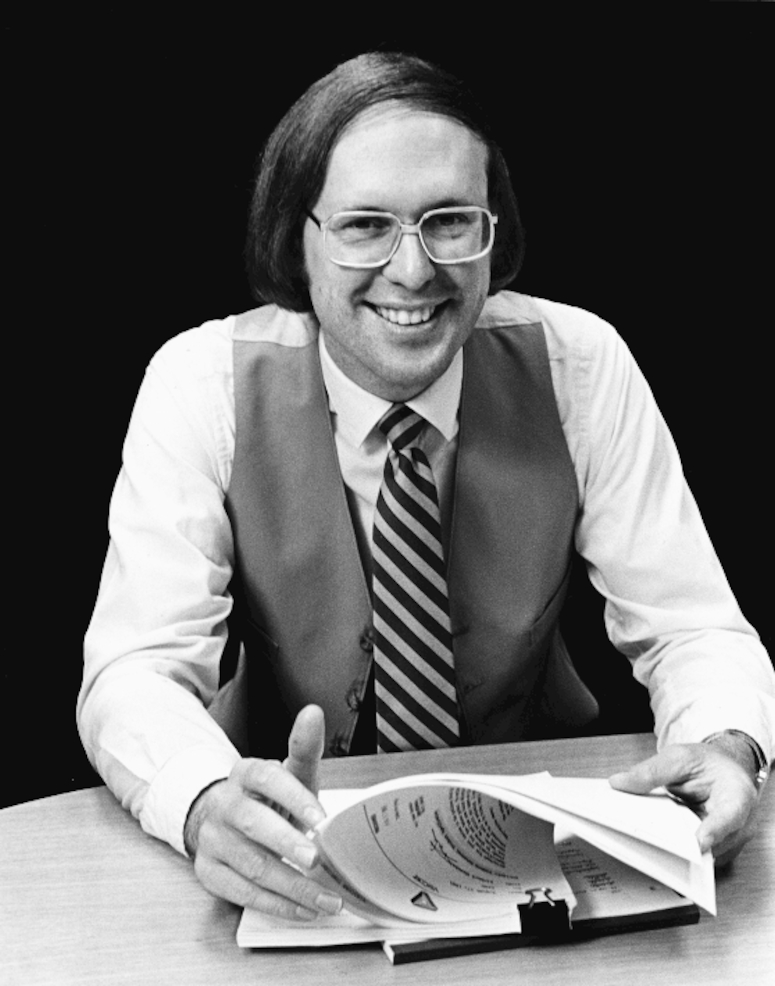

Figure 43. Dan Fylstra Fylstra’s Personal Software published the first electronic spreadsheet program, VisiCalc. (Courtesy of Liane Enkelis)

When the Altair came out, Cooper and Parsons drew up their plans. They decided to market business software for microcomputers. They hired a programmer, put him in a tiny room, and told him to write. They were busy writing, too. For a while, the two tried to sell turn-key systems—computers with sophisticated software that jumped into action when the machine was turned on. They got nowhere with that idea. What they really needed was an operating system, of which there were none as far as they knew, and maybe a high-level language. A chat with Peter Hollenbeck at Byte Shop in San Rafael, California, led them to Gary Kildall, CP/M, and Gordon Eubanks.

After months of development on Eubanks’s BASIC and their own business software, Cooper and Parsons were ready to start making their $50,000 a year. They placed the first ad for CBASIC in a computer magazine. After much agonizing, they also decided to throw in a mention of their business software. In small print at the bottom of the ad, it read “General Ledger $995.” They were prepared for an attack from hobbyists for selling a program that was almost triple the cost of the Altair itself.

It didn’t take long to get a response, but it was not the rant they feared. A businessman in the Midwest sent in an order for the General Ledger. Cooper made a copy of the program and inserted it in a zip-lock plastic bag along with a manual, a method of packaging software that became common. Before they knew it, back came a check for $995. Cooper, Parsons, and the whole Structured Systems Group staff went out for pizza.

Meanwhile, they kept working on software. The atmosphere was giddy and the style far from corporate. Parsons paced the office shirtless, while Cooper, hair down to midback, guzzled coffee that “would dissolve steel.” The two of them, wired on caffeine and the excitement of the $995 check, wrangled about potential markets and dealer terms. Parsons’s girlfriend made phone sales while sunbathing nude in the backyard behind their “office.”

Three weeks later, another order came in and the staff had another pizza. The pizza ritual continued for two months. People were sending in checks for thousands of dollars. Soon the Structured Systems Group was eating pizza for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Yes, there was money to be made writing software for personal computers.

Meanwhile, Back East…

Another early software company started up soon after the Altair announcement. In suburban Atlanta, far from Silicon Valley, several computer enthusiasts opened an Altair dealership called the Computersystem Center in December 1975. The group, including one Ron Roberts, had met as graduate students at Georgia Tech. They quickly realized that, as much as their customers wanted Altairs, they also wanted software to use with the machines. Business was slow at the outset, and they had lots of time on their hands to program.

The group contacted other Altair computer stores throughout the country and discovered that the need for software existed nationwide. In 1976, the group approached Ed Roberts with the idea of using the Altair name for their software distribution. Roberts recognized that software could help sell his machine and vice versa, and he agreed. Ron Roberts (no relation to Ed) became president of the Altair Software Distribution Company (ASDC). The idea was to distribute other people’s Altair software and to write a little of their own.

The group from Georgia called a meeting of Altair dealers in October 1976, and almost 20 stores (nearly all that existed) sent representatives. MITS representatives also attended the meeting because the dealers wanted to inform the MITS people about how delays in deliveries and mechanical failures were negatively affecting their business. Ron Roberts found that the Altair dealers had a lot in common. They all suffered from lack of software, hardware-delivery delays, hardware malfunctions, and the general public’s meager awareness of microcomputers. Of all those issues, “software was the biggest item on the agenda,” according to Ron Roberts.

Several dealers agreed right away at the meeting to purchase ASDC software. The initial software programs from ASDC were simple business packages: accounting, inventory, and, later on, a text editor. The accounting and inventory programs alone retailed for $2,000. Roberts and his colleagues considered the price reasonable; they’d previously worked in the minicomputer and mainframe industry where prices such as that were considered modest. Given the software vacuum at the time, ASDC was able to find buyers even at that hefty price. “We were making quite a bit of money,” Roberts recalled.

Ron Roberts later unhitched his wagon from that star after the sale of MITS to Pertec in 1977 and the subsequent fade-out of the Altair. CP/M was gaining popularity, and Roberts decided to convert the programs to enable them to run on Kildall’s operating system. This move allowed for sales for more than one brand of computer because many of the new hardware companies started in the wake of the Altair announcement adopted CP/M. Like a later de facto standard operating system from Microsoft, CP/M was machine-agnostic.

The word Altair now seemed inappropriate as part of the ASDC business name, so the company changed it to Peachtree Software after a downtown Atlanta street. “In the Atlanta area, it’s a quality name,” Roberts said. Peachtree employees were more businesslike than Cooper, Parsons, and the Structured Systems Group crew. Not only did they wear dress shirts instead of T-shirts, they even wore ties. They called their software product Peachtree Accounting and Peachtree Inventory.

In the fall of 1978, Roberts and one of his partners took the software part of the business and merged with Retail Sciences, a small computer consulting firm in Atlanta run by Ben Dyer, who had previously worked for a hardware-store chain (of the nuts-and-bolts variety). Following the merger, Peachtree released a general-ledger business package. Sales increased rapidly, as did the number of dealers carrying the Peachtree label, and soon it became one of the best-known and -respected names in the software field. Eventually Dyer changed the name of the whole company to Peachtree Software.

With SSG on the West Coast and Peachtree in the eastern part of the country, the software industry was establishing itself as an independent entity.