Apple Without Jobs

Without Jobs, Apple is just another Silicon Valley company, and without Apple, Jobs is just another Silicon Valley millionaire.

–Nick Arnett, Accidental Millionaire

Meanwhile, Steve Jobs found a use for some of the millions that he hadn’t put into NeXT, and at his former company, the engineers were getting restless.

Sculley Moves On

When Scully squeezed out Del Yocam and bypassed Jean-Louis Gassée, the Apple engineers were outraged. It wasn’t just that this former sugar-water salesman Sculley had the gall to name himself CTO of Apple, but Gassée, whom they would have picked as CEO had they been asked, was being shown the door.

Apple employees exhibited a lot of so-called attitude about their status within the industry. They were paid extremely well—at least the engineers were—and they felt as if they were artists. They generally believed that Apple made forward progress only by innovative leaps. This meant that everyone wanted to work on the hot projects; nobody wanted to be in an equivalent of the Apple II division when an equivalent of the Mac was in the works.

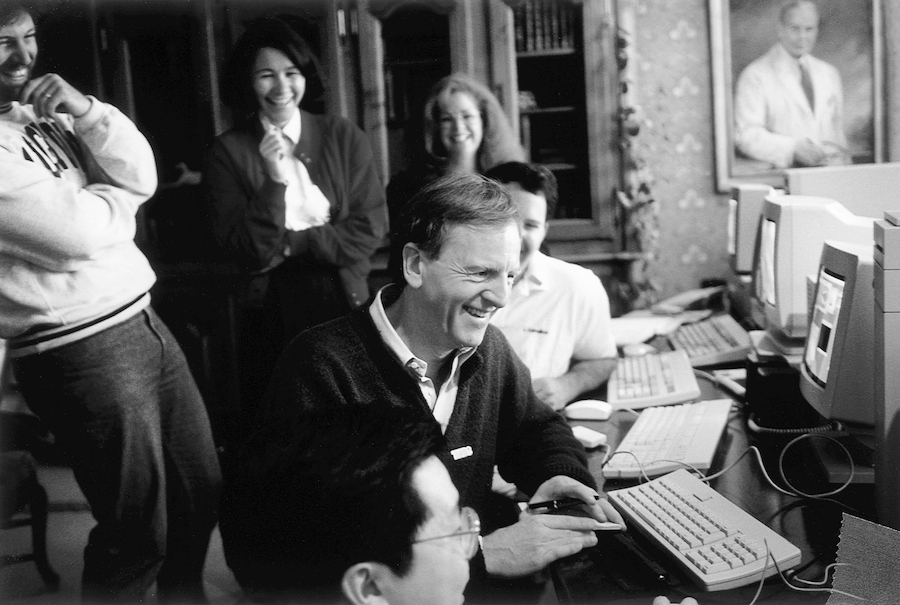

Figure 93. John Sculley Hand-picked by Jobs to be CEO, Sculley would eventually get Jobs stripped of all management power at Apple. (Courtesy of Rick Smolan)

One promising project for Apple during this era was something called Pink. Pink was the internal Apple code name for the next-generation replacement operating system that could run on different machines, including IBM compatibles. The significant talent was placed on the Jaguar project, a new machine using all-new hardware technology, and Pink, a next-generation operating system.

On April 12, 1991, Sculley demonstrated Pink to IBM. The IBM executives were impressed by what looked like the Mac operating system running on IBM hardware. By October, Apple and IBM had agreed to work together on the operating system, now to be called Taligent, and on a new microprocessor for a new generation of computers to be developed by each company.

This wasn’t a merger, or an acquisition, or a licensing deal—it was a collaboration with another company that had the potential to grab back a bigger chunk of the market for Apple. It was also evidence of the changing power structure of the industry: Apple could afford to work with its old nemesis IBM because IBM wasn’t the competition any more. Intel, which made the CPU for IBM and compatible computers, and Microsoft were the competition.

The deal with IBM was a bold move, and it may have been Sculley’s last significant contribution to the company. Apple’s longest-tenured CEO was getting burned out. He had already handed the presidency to Spindler, and now he was becoming distracted, ready to move on to something else.

That something else might have been a very different kind of job from running a personal-computer company. Sculley was spending a lot of time with his new friends, Arkansas governor Bill Clinton and Hillary Rodham Clinton. It was 1992, and the Arkansas governor was running hard for president. There was talk of a cabinet position for Sculley, even talk that he was on Clinton’s short list for the vice presidency. (He didn’t get it, of course, but he did get to sit next to Hillary at the inauguration.) Little wonder he seemed a bit disconnected at marketing planning meetings.

He could always move to IBM. Not only were they recruiting him, but it looked as though he was going to be offered the top spot. IBM might not be as dynamic as Apple, but it was a lot bigger, and it would mean a move back to the East Coast, which appealed to Sculley.

That year he told Apple’s board that he wanted to leave. April 1993 would be his tenth anniversary, and that was long enough, he said. When they asked his advice for the company, he was blunt: sell Apple to a larger company such as Kodak or AT&T. The board asked him to stay until the sale happened.

But the sale didn’t happen, and Apple’s earnings dropped from a peak of $4.33 per share in 1992 to $0.73 per share in 1993 as competition mounted. On June 18, 1993, John Sculley was out the door and Michael Spindler was now the CEO of Apple.

Spindler’s first act as CEO was to cut 16 percent of the staff. It was necessary. Apple was running an aging operating system on a dead-end microprocessor line. The Motorola 68000 line was nearing the end of its life, and Apple was committed to move to a new processor, the PowerPC chip being codeveloped with IBM and Motorola.

Spindler presided over the PowerPC transition, which was itself an impressive technical achievement. Apple had produced some 70 models of Macs on the 68000 family, and its operating system was written for the 68000 chip. Moving to the PowerPC meant rethinking both hardware and software, basically rebuilding everything the company was doing, plus asking all third-party developers who wrote programs for Macintosh to rewrite their software, too. It was like rebuilding a car while driving it in the passing lane on the freeway.

Apple pulled it off, but not without some help. A company named Metrowerks came through at the last minute with the development software that third-party developers needed to convert their software to the PowerPC. Apple hadn’t managed to get a decent development system together in time. In March 1994, Apple began selling PowerPC machines, and they were immediately successful.

The other part of the formula for getting Apple back in shape—the new operating system—was in trouble. The Taligent effort (Apple’s joint venture with IBM) was failing; it was a $300 million casualty of committee design and lack of focus. Moreover, Apple was still pursuing all the visionary research and development projects that had been launched in Sculley’s golden years, but only allocating two or three programmers when there had been dozens before. Those projects ate resources with little chance of ever producing results.

Merger talks took place, including discussions of joining Compaq, but they went nowhere.

The ever-contentious push to license the Mac operating system finally bore fruit in 1995. The first licensee was Power Computing, a company started by Steve Kahng, who had designed a top-selling PC clone—the Leading Edge PC—10 years before. Unfortunately, it was too late. Apple’s fruit had dried up. The Mac-clone market didn’t take off as it might have earlier. The Mac operating system appeared to be on its last legs. Power Computing did all right for itself, but it wasn’t helping Apple’s bottom line.

Christmas was a sales disaster. Fujitsu edged in on the Japanese market, formerly a reliable income source for Apple. By January 1996, it was time for more layoffs.

Apple had been aggressively pursuing a buyer since 1992; now Sun Microsystems stepped in with an offer. At two-thirds the stock valuation, it was a slap in the face, symbolic of how badly Apple’s reputation had deteriorated. It was becoming conventional wisdom among even the best business analysts to doubt whether a viable business plan for Apple would emerge.

A lot had gone out of the company. Jobs was gone. Woz was technically an employee but hadn’t been involved in years. Jean-Louis Gassée, passed up for promotion, had moved on and, like Jobs, had started his own computer company, Be Labs. Chris Espinosa, who had been there virtually from the beginning, riding his moped to the Apple offices at age 14 and writing the first user manual for the Apple II while in college, was in his thirties now, married, with children. He remembered an Apple no one else in the company had known, and it pained him to see it dying. He had never had another job, and wasn’t eager to go looking for one. He decided just to hang on for the end game. “I might as well stick around to turn out the lights,” he told himself.

The end game was about to begin, apparently. Spindler was fired on January 30, and Apple board member and reputed turnaround artist Gilbert Amelio was named CEO. Apple needed a turnaround artist, all right. The company was on life support.

Pixar

For the next chapter in Apple’s life, it helps to flash back to 1975, the year that the Altair was announced. When Paul Allen was spotting that Popular Electronics cover in Harvard Square and rushing to tell Bill Gates that they had better do something or they would be left out, two computer-graphics experts at the New York Institute of Technology were getting together to try to do something innovative in computer animation. They were bright and creative and they worked hard, and by 1979, Edmund Catmull, Alvy Ray Smith, and the team they assembled had come up with some nifty tricks. They moved to Marin County, California, to work for George Lucas at Industrial Light & Magic, which became the premiere special-effects house and changed the way movies are made.

Seven years later, frustrated that Lucas’s game plan did not match theirs, they began looking for a way out. Lucas gave it to them when he sold their division to Steve Jobs, who had recently sold his Apple stock and had a spare $10 million to invest. The resulting company was called Pixar.

Pixar was not a personal-computer company, but it was a company that would not have existed without the technology of the personal-computer revolution. It was a precursor to other businesses that would expand personal-computer technology into new areas, and is worth a look for that reason. But Pixar is also significant for the clues it gives to the growth of Steve Jobs in his years away from Apple.

Pixar ate another $50 million of Jobs’s money over the next five years, as Jobs encouraged the Pixar employees to push the state of the art as far as possible. That was exactly what Catmull and his team had in mind; during these years, Pixar employees published seminal articles on computer animation, won awards, and invented most of the cutting-edge techniques that made it possible to do computer-animated feature films.

Jobs had once again placed himself among bright people working on innovative technologies. If building computers had become a boring commodity business, computer animation was a field hot with creative fire. Jobs was, of course, encouraging the crew at Pixar to do their absolute best. But that was a subtle change for Steve, and showed that he had learned something from his experience at Apple. The Pixar people were already driven to push the state of the art, so he didn’t need to drive them. His role at Pixar was more that of an enabler.

Pixar was a collection of technological artists, and Steve Jobs, an artist at heart, was their rich patron. But the artists were about to start paying the rent.

Pixar discovered that its strength lay in content development more than in building devices or writing software, although it did game-changing work in both those areas. In 1988, Pixar’s Tin Toy became the first computer-animated film to win an Academy Award. Jobs took notice. Then, in 1991, Disney signed a three-picture deal with Pixar, including a movie called Toy Story.

The Pixar team put everything they had into Toy Story. By the time the box-office receipts had been counted in 1995, Toy Story was a major success, Pixar was a force in the movie industry, and Jobs himself had become a billionaire. He promptly went to Hollywood and, over lunch with Disney head Michael Eisner, negotiated a new contract that was much more favorable to Pixar.

Although he never succumbed to the lures of Hollywood life, Steve Jobs was now a player in that world, the newest movie-industry billionaire, dealing with the biggest names in Hollywood. Compared to that, NeXT was small change. And Apple, his first company—well, it was on the ropes.

The Return of Steve Jobs

Turnaround artist Gilbert Amelio had been named the new CEO at Apple, as well as chair of the board; Mike Markkula accepted a demotion to vice chair.

The operating system was the biggest problem Apple had to solve. Taligent, the joint venture with IBM, had fallen apart and Copland, the in-house operating-system project, was going nowhere fast. Amelio’s chief technologist, Ellen Hancock, recommended that Apple buy or license an operating system from someone else.

There were at least three options on the table: license Sun’s operating system and put a Mac face on it; do the same with Microsoft’s NT operating system; or purchase Jean-Louis Gassée’s BeOS outright. Gassée, Apple’s ex–head of engineering, had formed Be Labs when he left Apple, taking key employee Steve Sakoman with him, and Sakoman had come up with both a computer, the BeBox, and a highly regarded, multimedia-savvy (albeit not yet fully polished) operating system, BeOS.

The press was having fun guessing which way Apple would turn. BeOS looked like the best fit. Gassée was a former top manager at Apple and was popular with Apple’s engineers, the Be operating system had a friendly feel that seemed very Mac-like, and the technology was state of the art. It was easy to imagine BeOS as the future of the Mac and Gassée back in charge of (at least) engineering. But Hancock told the press cryptically, “Not everyone who is talking to us is talking to you.”

Meanwhile, Oracle’s unpredictable founder Larry Ellison, now a member of the Silicon Valley billionaire boys’ club, was stirring things up by hinting that he would buy Apple and let his good friend Steve Jobs run it. Jobs gave no credence to Ellison’s hints, and no one took Ellison too seriously, but Jobs did at one point call Del Yocam, Apple’s COO from the company’s best days and now CEO of a restructured and renamed Borland (to Inprise), to bend Yocam’s ear about their running Apple together.

But no one really took Ellison seriously. So when Apple’s decision was announced hours after it was made, it caught the industry completely by surprise. Apple would acquire NeXT Inc., lock, stock, and barrel, and use its technology to build a next-generation operating system for its computers. Apparently when Hancock had said that not everyone talking to Apple was talking to the press, she was talking about Steve Jobs. And while his staff had made the initial contact with Apple, it was predictably Jobs himself who shut out Be Labs and closed the deal.

One detail of the announcement overshadowed the rest for sheer drama: Steve Jobs was coming back to Apple.

The deal made Jobs a part-time consultant, who reported to CEO Gilbert Amelio and who was charged with helping to articulate Apple’s next-generation operating strategy, but with no one reporting to him, no clearly articulated responsibilities, no seat on the board, and no power.

No power? Amelio didn’t know Steve Jobs.

Apple unquestionably needed saving. After four profitable quarters in fiscal 1995, it had lost money quarter after quarter, gone through major restructuring and layoffs, and was losing market share rapidly. Third-party software developers were choosing almost routinely to develop for Windows first, and then, maybe, to port their products to the Mac. Apple stock was falling and brokerage firms were recommending not to buy Apple. The press was sounding its death knell.

People weren’t buying Apple’s computers, either, at least not enough to maintain Apple’s already tiny market share, because they didn’t see any advantage in the Macintosh over Windows machines. This was partly because of the aggressive marketing of the Windows 95 release by Microsoft, which included purchasing the rights to the Rolling Stones’ “Start Me Up” for $10 million, but mostly because of Apple’s demonstrated inability to deliver a long-delayed overhaul of the Mac operating system.

By the end of 1996 Apple’s future was in question, but some observers thought the company could be turned around if it got three things: focused management, a better public image, and a next-generation operating system. And it needed all of them right away.

Some thought that Amelio and the team he had put together were that focused management. And NeXTSTEP really was a next-generation operating system, not an implausible idea. Even though it was more than half the age of the doddering Macintosh operating system, it had everything a modern operating system should have—things like true multitasking. The NeXT team had designed well, and NeXTSTEP was field-tested. As for the change in Apple’s public image…

Three weeks after the announcement, Amelio took the stage for his keynote address at the Macworld Expo in San Francisco, the biggest Macintosh event of the year, the place where Apple often laid out its plans for the coming year. The room was jammed, and attendees had to find sitting or standing room in the aisles. The word was out that Apple had bought NeXT and that Steve Jobs was back, but little more was known. The news was dramatic, but the unknowns were even more of a draw.

Amelio laid out the essence of the plan plainly: Apple would produce a new operating system, based very closely on NeXTSTEP, to run on its PowerPC hardware. NeXTSTEP, the operating system of Steve Jobs’s company, was Apple’s future.

Then he introduced Steve Jobs.

The crowd jumped to its feet and applauded wildly. When things finally quieted down, Jobs described NeXTSTEP and his view of the challenges facing Apple. He could have said anything. He had the crowd in his hand.

Later, Amelio called Jobs back to the stage, along with cofounder Steve Wozniak. The packed house rose to its feet again, and again there was thunderous applause.

It was a moment.

For Steve Jobs it was also a symbol of some kind of a homecoming, and like all homecomings, this one was remarkable for what had changed as well as for what had not. A great deal was now different for Steve Jobs than it was when he left Apple more than a decade earlier. He was married now and had a family. The lack of success at NeXT would have been humbling to anyone else, and probably was even to Jobs. But by selling NeXT he had finally paid his debt to its long-suffering employees (and had stock options that were now worth real money). And both Jobs and Apple were simply older; the company was now as old as the man was when he and Steve Wozniak founded it.

What followed was not quite what Amelio expected. The correct word for it is coup. Within weeks, Jobs had his chosen managers in place. NeXT veterans Jon Rubenstein and Avi Tevanian were now totally in charge of Apple’s hardware and software divisions. By midyear, Jobs had eased Amelio out of the company entirely, had engineered a new board of directors loyal to Jobs, and was appointed interim CEO with unchallenged authority over every aspect of the company’s business. Months later, Amelio was still trying to put a favorable spin on the coup.

Steve Jobs was back. But could even its charismatic cofounder rescue Apple?