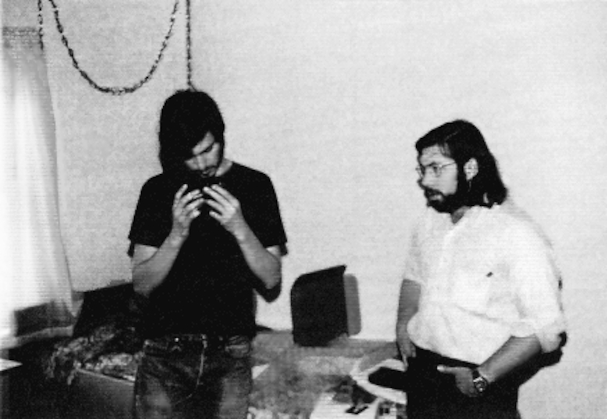

Jobs and Woz

Woz was fortunate to hook up with an evangelist.

—Regis McKenna, high-tech marketing guru

There were still orchards in Santa Clara Valley.

But by the 1960s it was no longer the largest fruit-producing area in the world. It was starting to transition to urban sprawl as the electronics and semiconductor companies began taking over, and for the son of an engineer in Sunnyvale it was easier to pick up a spare transistor than to find somewhere to pick an apple.

The Prankster

In 1962, an eighth-grade boy in Sunnyvale built an addition-subtraction machine out of a few transistors and some parts. He did all the work himself, soldering wires in the backyard of his suburban home in the heart of what became Silicon Valley. And when he entered the machine in a local science fair, no one who knew him was surprised that he won the top award for electronics. He had designed a tic-tac-toe machine two years earlier and, with a little help from his engineer dad, had assembled a crystal radio in the second grade.

The boy, born Stephen Gary Wozniak, but called Woz by his friends, was brilliant, and when a problem caught his interest, he worked relentlessly to solve it. When he enrolled in Homestead High School in 1964, Woz quickly became one of the top math students there, although electronics remained his true passion. Unfortunately for the teachers and administrators of Homestead High, that wasn’t his only passion.

Woz was a prankster, and he applied the same ingenuity and determination to carrying out his practical jokes as he did to building electronics. He spent hours at school concocting the perfect prank. His jokes were clever and well executed, and he usually emerged from them unscathed.

But not always. Once, Woz got the bright idea to wire up an electronic metronome and plant it inside a friend’s locker, its bomblike ticking audible to anyone standing nearby. “Just the ticking would have sufficed,” Woz said, “but I taped together some battery cylinders with the labeling removed. I also had a switch that sped up the ticking when the locker was opened.” But it was the high-school principal who fell for the trick. Bravely snatching the “bomb” from the locker, he ran out of the building with it. Wozniak thought the whole incident was hilarious. Post-9/11 he would probably have been expelled. At the time, the principal showed his appreciation of the joke by suspending Woz for two days.

The Cream Soda Computer

Soon after that, Steve Wozniak’s electronics teacher, John McCullum, decided to take him in tow. Woz clearly found high school less than stimulating, and McCullum saw that his pupil needed a genuine challenge. Although Woz loved electronics, the class McCullum taught was nowhere near demanding enough. McCullum worked out an arrangement with Sylvania Electronics whereby Wozniak could visit the company’s nearby facilities during school hours to use their computers.

Woz was enthralled. For the first time, he saw the capabilities of a real computer. One of the machines he played with was a Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-8 minicomputer. “Play” for Woz was an intense and engrossing activity. He read the PDP-8 manual from cover to cover, soaking up the information about instruction sets, registers, bits, and Boolean algebra. He studied the manuals for the chips inside the PDP-8. Confident of his newfound expertise, within weeks Woz began drawing up plans for his own version of the PDP-8.

“I designed most of the PDP-8 on paper just for the heck of it. Then I started looking for other computer manuals. I would redesign each [computer] over and over, trying to reduce my chip count, and using newer and newer TTL chips in my designs. I never had a way to get the chips to build one of these designs as my own.”

He knew that he was going to build computers himself one day—he hadn’t the slightest doubt of that. But he wanted to build them now.

During the years Steve Wozniak attended Homestead High, semiconductor technology advances made possible the creation of minicomputers like the PDP-8. The PDP-8 was one of the most popular, while the Nova, produced by Data General in 1969, was one of the most elegant. Woz was enchanted by the Nova. He loved the way its programmers had packed so much power into a few simple instructions. The Data General software was not just powerful; it was beautiful. The computer’s chassis also appealed to him. While his buddies were plastering posters of rock stars on their bedroom walls, Woz covered his with photos of the Nova and brochures from Data General. He then decided—and it became the biggest goal in his life—that he would one day own his own computer.

Woz was not the only student in Silicon Valley with electronics dreams. Many of his fellow students at Homestead High had parents in the electronics industry. Having grown up with new technology around them, these kids were accustomed to watching their parents play around with oscilloscopes and soldering irons in the garage. And Homestead High had teachers who encouraged their students’ interests in technology. Woz may have followed his dream more single-mindedly than the others, but the dream was not his alone.

The dream was, however, highly unrealistic. In 1969, it was almost unthinkable that individuals could own their own computers. Even minicomputers like the Nova and the PDP-8 were priced to sell to research laboratories. Nevertheless, Woz went on dreaming. He did well on his college entrance exams but hadn’t given much thought to which college to attend. When he eventually made his choice, it had nothing to do with academics. On a visit to the University of Colorado with some friends, the California boy saw snow for the first time and was enchanted. He concluded that Colorado would suffice. His father agreed he could go there for a year, at least.

At the University of Colorado, Woz played bridge intensely, designed more computers on paper, and engineered pranks. After creating a device to jam the television in his college dorm, he told trusting hallmates that the television was badly grounded, and they would have to move the outside antenna around until they got a clear picture. When he had one of them on the roof in a sufficiently awkward position, he quietly turned off his jammer and restored the television reception. His hallmate remained contorted on the roof, for the public good, until the prank was revealed.

Woz took a graduate computer class and got an A+. But the computer center allocated the computer’s time jealously and Woz wrote so many programs that he ran his class over its computer-time budget by a large multiple. His professor instructed the computer center to bill him. Woz was afraid to tell his parents and he never went back to school there. After his first year, he came home and attended a local college. For a summer job in 1971, he worked at a small computer company called Tenet Incorporated that built a medium-scale computer. He enjoyed it enough to stay on into the fall rather than returning to school.

The same summer he started work, Woz and his old high school friend Bill Fernandez actually built a computer out of parts rejected by local manufacturers because of cosmetic defects. Woz and Fernandez stayed up late cataloging the parts on the Fernandez family’s living-room carpet. Within a week, Woz showed up at his friend’s house with a cryptic penciled diagram. “This is a computer,” Woz told Fernandez. “Let’s build it.” They worked far into the night, soldering connections and drinking cream soda. When they finished, they named their creation the Cream Soda Computer; it had the same sort of lights and switches as the Altair would more than three years later.

Woz and Fernandez telephoned the local newspaper to boast about their computer. A reporter and a photographer arrived at the Fernandez house, sniffing out a possible “local prodigy” cover story. But when Woz and Fernandez plugged in the Cream Soda Computer and began to run a program, the power supply overheated. The computer literally went up in smoke, and with it Woz’s chance for fame, at least for the moment. Woz laughed the incident off and went back to his paper designs.

The Two Steves Meet

Figure 54. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak Jobs and Woz look over an early Apple I circuit board. (Courtesy of Margaret Kern Wozniak)

Besides assisting with the Cream Soda Computer, Bill Fernandez did something that would profoundly change the life of his friend. He introduced Woz to another electronics hobbyist, an old friend of his from junior high school. Although a good number of Silicon Valley students were interested in electronics because their parents were engineers, this friend, a couple of years behind Fernandez in school, was an anomaly in that respect. His parents were blue-collar workers, unconnected to the computer industry. This friend, a quiet, intense, long-haired boy, was named Steven Paul Jobs.

Although Jobs was five years younger than Woz, the two hit it off immediately. Both were fascinated with electronics. In Woz’s case, this led to the concentrated study of schematics and manuals and lengthy sessions designing electronic gadgets. Jobs was as intense as Woz, but his passion showed itself in different ways, and it sometimes got him into trouble.

Jobs confessed to being a terror as a child. He claimed that he would have “ended up in jail” if it hadn’t been for a teacher, Mrs. Hill, who moved him ahead a year to separate him from a boisterous buddy. Mrs. Hill also bribed Jobs to study. “In just two weeks, she had figured me out,” Jobs recalled. “She told me she’d give me five dollars to finish a workbook.” Later, she bought him a camera kit. He learned a lot that year.

As an adolescent, Jobs had an unshakable self-confidence. When he ran out of parts for an electronics project he was working on, he simply picked up the phone and called William Hewlett, cofounder of Hewlett-Packard. “I’m Steve Jobs,” he told Hewlett, “and I was wondering if you had any spare parts I could use to build a frequency counter.” Hewlett was understandably taken aback by the call, but Jobs got his parts. The 12-year-old was not only very convincing but also surprisingly enterprising. He made money at Homestead High by buying a broken stereo or other piece of electronic equipment, fixing it, and selling it at a profit.

But it was a mutual love of practical jokes that cemented the relationship. Jobs, Woz discovered, was another born prankster. This led the two to engage in a rather shady early business enterprise.

Blue Boxes

Woz returned to school, this time to the University of California at Berkeley, to study engineering. He had resolved to take school more seriously and even enrolled in several graduate courses. He did well, even though by the end of the school year he was spending most of his time with Steve Jobs building blue boxes.

Woz first learned about these sneaky devices for tricking the phone network and making free long-distance phone calls in a piece in Esquire magazine. The story described a colorful character who used such a device as he crisscrossed the country in his van, the FBI panting in pursuit. Although the story was a blend of fiction and truth, the descriptions of the blue box sounded very plausible to the budding engineer. Before Woz even finished the piece, he was on the phone to Steve Jobs, reading him the juicy parts.

The Esquire story was drawn from the extraordinary real-life experiences of John Draper, a.k.a. Captain Crunch. Draper had discovered that a whistle included in boxes of Cap’n Crunch cereal had an interesting ability. Blow the whistle directly into a telephone receiver and it would exactly mimic the tones that caused the central telephone circuitry to release a long-distance trunk line. With it, you could make long-distance calls for free.

Draper expanded on this trick with electronics, essentially inventing phone phreaking and becoming its prime practitioner, traveling around the country showing people how to build and operate these blue boxes. True phreaking, purists said, was motivated solely by the intellectual challenge of getting past a complex network of circuits and switches. The telephone company, however, took a dim view of the enterprise and prosecuted the phreaks whenever it could catch them.

With his customary thoroughness, Wozniak collected articles on phone-phreaking devices of all kinds. In a few months, he had become a phone-phreaking expert himself, known to insiders by the nickname Berkeley Blue. Perhaps it was inevitable that Woz’s newfound infamy would get back to the man who had inspired him. One night a van pulled up outside Woz’s dorm.

Wozniak was thrilled to meet John Draper. The two quickly became good friends, and together they used phone-phreak techniques to tap information from computers all over the United States. At least once they listened in on an FBI phone conversation, according to Wozniak.

It was Jobs, however, who made this pastime turn a profit. Jobs got into phone phreaking, too, later claiming that he and Woz had called around the world several times and once woke the Pope with a blue-box call. Soon Wozniak and Jobs had a neat little business marketing phone-phreaking boxes. “We sold a ton of ’em,” Woz would later confess. When Jobs was still in high school, Woz made most of the sales to students in the Berkeley dorms. In the fall of 1972, when Jobs entered Reed College in Oregon, they were able to broaden their market.

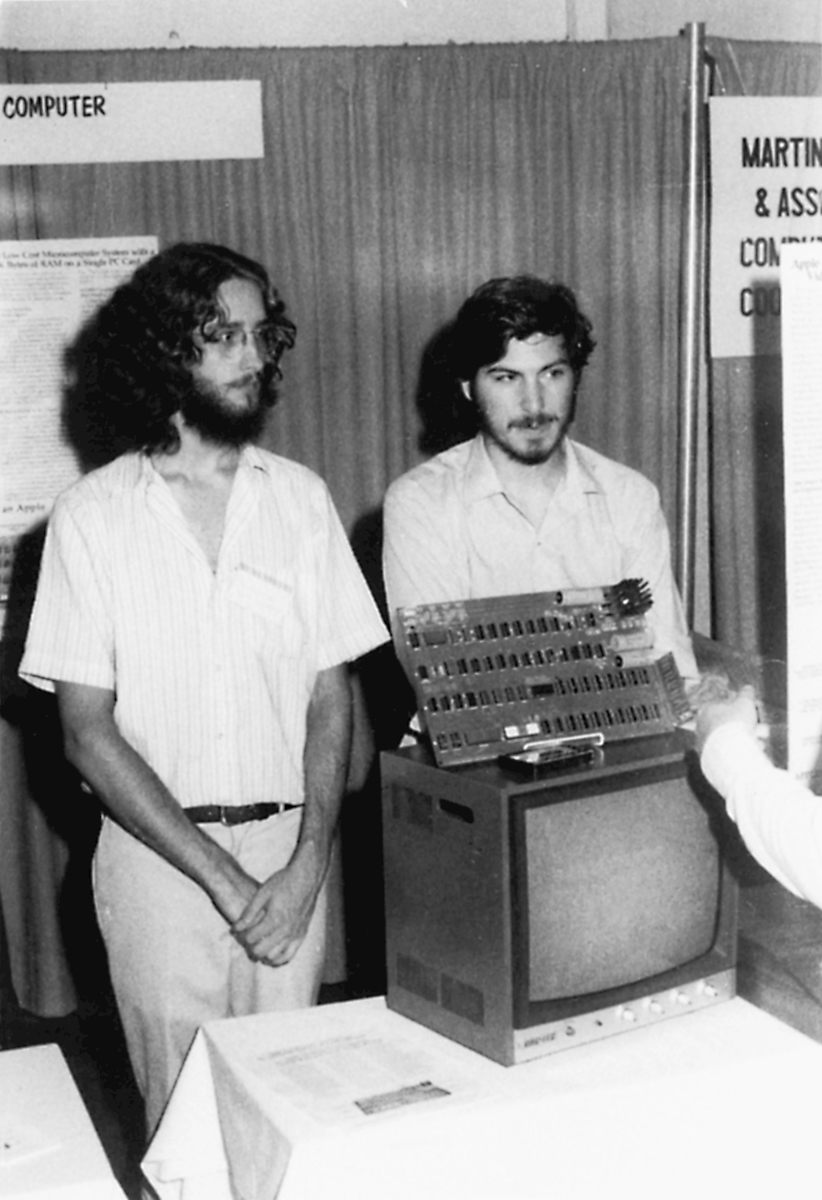

Figure 55. Dan Kottke and Steve Jobs Kottke traveled to India with Jobs and later worked for Apple. Here he and Jobs are manning the booth at an early computer show. (Courtesy of Dan Kottke)

Buddhism

Jobs had considered going to Stanford, where he had attended some classes during high school. “But everyone there knew what they wanted to do with their lives,” he said. “And I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life at all.” On a trip to Reed, he had fallen in love with the school, seeing it as a place where “nobody knew what they were going to do. They were trying to find out about life.” When Reed accepted him, he was ecstatic.

But once at Reed, Jobs lived as a recluse. As the son of working-class parents, he may have felt out of place in a school populated largely by upper-class youths. He began investigating Eastern religions, staying up late at night with his friend Dan Kottke to discuss Buddhism. They devoured dozens of books on philosophy and religion, and at one point Jobs became interested in primal therapy.

In the year Jobs spent at Reed, he seldom attended class. After six months, he dropped out but managed to remain in the dorm. “The school sort of gave me an unofficial scholarship. They let me live on campus and looked the other way.” He remained for over a year, attending classes when he felt like it, spending much of his time studying philosophy and meditating. He converted to vegetarianism and lived on Roman Meal cereal, a box of which cost less than 50 cents and would feed him for a week. At parties he tended to sit quietly in a corner. Jobs seemed to be clearing things out of his life, searching for some utter simplicity.

Although Woz had little interest in Jobs’s nontechnical pursuits, his friendship with Jobs remained strong. Woz frequently drove up to Oregon on weekends to visit Jobs.

Breakout

Woz took a summer job in 1973 at Hewlett-Packard, joining Bill Fernandez, who was already working there. Woz had only just finished his junior year, but the lure of Silicon Valley’s most prestigious electronics company was hard to resist. College would have to wait once again as Woz continued his education in the firm’s calculator division. This was the pre-Altair era when calculators were a hot commodity, and HP was manufacturing the HP-35 programmable calculator. Wozniak realized just how much the device resembled a computer. “It had this little chip, serial registers, and an instruction set,” he thought. “Except for its I/O, it’s a computer.” He studied the calculator design with the same energy that he had applied to the minicomputers of his high-school days.

After his year at Reed College, Jobs returned to Silicon Valley and took a job with a young video-game company called Atari. He stayed until he had saved enough money for a trip to India that he and Dan Kottke had planned. The two had long discussions about the Kainchi Ashram and its famous inhabitant, Neem Karoli Baba, a holy man described in the popular book Be Here Now. Jobs rendezvoused with Kottke in India, and together they searched for the ashram. When they learned that Neem Karoli Baba had died, they drifted around India, reading and talking about philosophy.

When Kottke ran out of money, Jobs gave him several hundred dollars. Kottke went on a meditation retreat for a month. Jobs didn’t go with him, but instead wandered the subcontinent for a few months before returning to California. On his return, Jobs went back to work for Atari and reconnected with his friend Woz, who was still at HP. Jobs himself had worked at Hewlett-Packard years before, on the strength of that brazen phone call to Bill Hewlett asking for spare parts. Now he was at Atari, and though he was still just as brash and just as convinced that he could get anything he wanted, he had been changed in subtle ways by his year at Reed and his experiences in India.

Woz was still a jokester at heart. Every morning before he left for work he would change the outgoing message on his telephone answering machine. In a gravelly voice and thick accent, he would recite his Polish joke for the day. Woz’s Dial-A-Joke phone number became the most frequently called phone number in the San Francisco Bay Area, and he had to argue more than once with the telephone company to keep it going. The Polish American Congress sent him a letter asking him to cease and desist with the jokes, even though Woz himself was of Polish extraction. So Wozniak simply made Italians the butt of his jokes instead. When the attention faded, he went back to Polish jokes.

In the early 1970s, computer arcade games were becoming popular. When Woz spotted one of those games, Pong, in a bowling alley, he was inspired. “I can make one of those,” he thought, and immediately went home and designed a video game. Even though its marketability was questionable (when a player missed the moving blip, “OH SHIT” flashed on the screen), the programming on the game was first-rate. When Woz demonstrated his game for Atari, the company offered him a job on the spot. Being comfortable with his position at HP, Woz turned them down.

But he was devoting much of his time to Atari technology. Woz had already dropped a small fortune in quarters into arcade games when Jobs, who often worked nights, began sneaking him into the Atari factory. Woz could play the games for free, sometimes for eight hours at a stretch. It worked out well for Jobs, too. “If I had a problem, I’d say, ‘Hey, Woz,’ and he’d come and help me.”

At the time, Atari wanted to produce a new game, and company founder Nolan Bushnell gave Jobs his ideas for what came to be called Breakout, a fast-paced game in which the player controls a paddle to hit a ball that breaks through a wall, piece by piece. Jobs boasted he could design the game in four days, secretly planning to enlist Woz’s help.

Jobs was always very persuasive, but in this case he didn’t have to bring out the thumbscrews to get his friend to help him. Woz stayed up for four straight nights designing the game, and still managed to put in his regular hours at Hewlett-Packard. In the daytime, Jobs would work at putting the device together, and at night Woz would examine what he’d done and perfect the design. They finished it in four days.

The experience taught them something: they could work well together on a tough project with a tight deadline and succeed.

Woz also learned something else, but not until much later. The $350 Jobs gave Woz as his share for the work was considerably less than the $6,650 cut that Jobs kept for himself. With Jobs, friendship only went so far.