IBM

IBM is a pretty big company.

–Bill Gates

Hewlett-Packard and Xerox had made less-than-impressive entries into the personal-computer market, and there was intense curiosity within that industry about how IBM would fare. The megafirm was considered successful in almost everything it had tried. Its reputation had held up at least since the mid-1960s, when IBM owned two-thirds of the computer market. And when IBM chief Thomas J. Watson, Jr., bet the company on a new semiconductor-based computer line that instantly made IBM’s most profitable machines obsolete—and the bet paid off—IBM only appeared all the more infallible.

In 1980 a new CEO, Frank Cary, proved willing to risk if not the company, at least some of its pristine reputation on a very un-IBM venture.

Taking a Meeting with IBM

In July of 1980, Bill Gates, busily developing a BASIC for Atari, received a phone call from a representative of IBM. He was surprised, but not greatly so. IBM had called once before about buying a Microsoft product, but the deal had fallen through. However, this communication was more tantalizing. IBM wanted to send some researchers from its Boca Raton, Florida, facility to chat with Gates about Microsoft. Gates agreed without hesitation. “How about next week?” he asked. “We’ll be on a plane in two hours,” said the IBM man.

Gates proceeded to cancel his next day’s appointment with Atari chairman Ray Kassar. “IBM is a pretty big company,” he explained sheepishly.

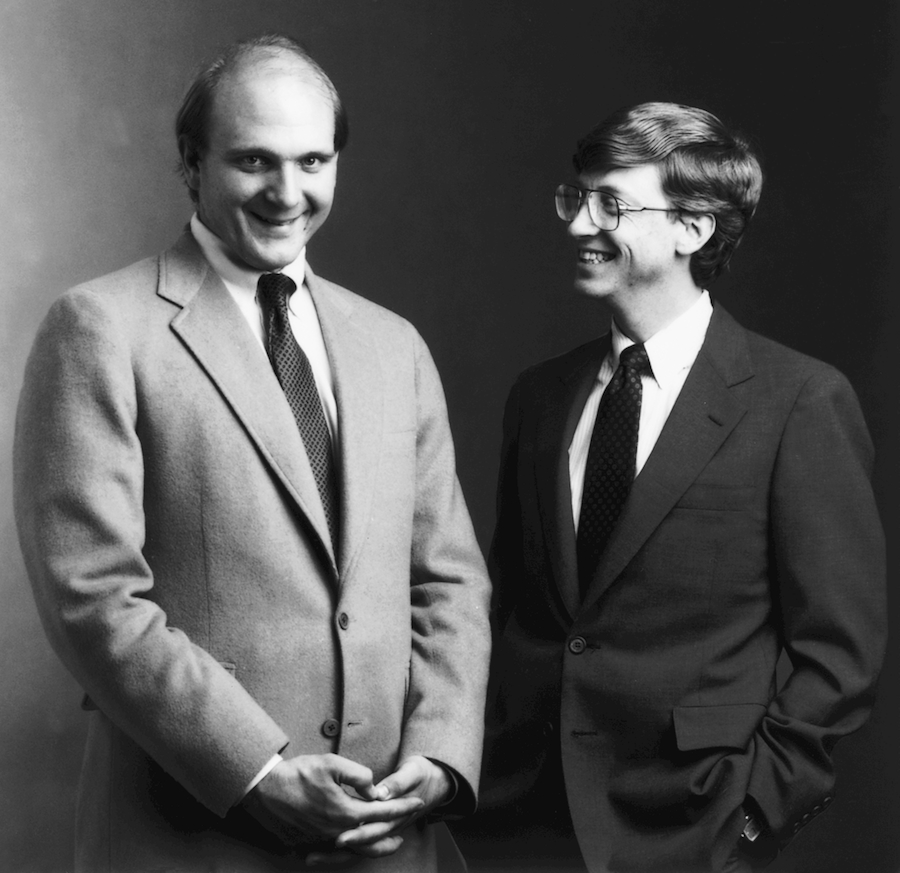

Because IBM was indeed a pretty big company, he decided to turn to Steve Ballmer, his advisor in business matters and a former assistant product manager at Procter & Gamble. Gates had known Ballmer when he attended Harvard in 1974. In 1979, when Gates decided that Microsoft was getting difficult to manage, he hired Ballmer. Ballmer was brash and ambitious. After Harvard, he had entered Stanford University’s MBA program but had dropped out to start making money sooner.

Ballmer had been glad to join Microsoft. He was enthusiastic about the little software company, and he liked Bill Gates. At Harvard, he had convinced Gates to join his men’s club. As an initiation rite, he dressed his friend in a tuxedo, blindfolded him, brought him to the student cafeteria, and made him talk to other students about computers. Gates’s dealings with IBM would remind him of this experience.

Gates liked Ballmer, too. Gates had played poker during the evenings in the Harvard dorms, and after being cleaned out, he often went to Ballmer to describe the game. As they started working together at Microsoft in 1980, Gates found he still enjoyed discussing things with his friend, who quickly became one of his closest business confidants, and he naturally turned to him after IBM’s call.

Figure 85. Steve Ballmer and Bill Gates Gates’s ebullient college buddy would go on to replace him as Microsoft CEO. (Courtesy of Sarah Hinman, Microsoft Museum)

“Look, Steve,” Gates said, “IBM is coming tomorrow. We better show those guys a little depth. Why don’t we both sit in on the meeting?”

Neither of them could be sure that the call was anything special, but Gates couldn’t help getting worked up over it. “Bill was superexcited,” Allen later recalled. “He hoped they’d use our BASIC.” Thus, Ballmer said, he and Gates “did the thing up right,” meaning suit and tie, which was unusual attire at Microsoft.

Before the meeting began, IBM asked Gates and Ballmer to sign an agreement promising not to tell IBM anything confidential. Big Blue used this device to protect itself from future lawsuits. Hence, if Gates revealed a valuable idea to the company, he could not sue later on if IBM exploited the concept. IBM was familiar with lawsuits; adroit use of the legal system had played an important part in its long control of the mainframe-computer business. It all seemed rather pointless to Gates, but he agreed.

The meeting seemed to be little more than an introductory social session. Two of the IBM representatives asked Gates and Ballmer “a lot of crazy questions,” Gates recalls, about what Microsoft did and about what features mattered in a home computer. The next day Ballmer typed up a letter to the IBM visitors thanking them for the visit and had Gates sign it.

Nothing happened for a month. In late August, IBM phoned again to schedule a second meeting. “What you said was really interesting,” the IBM representative told Gates. This time IBM would send five people, including a lawyer. Not to be outdone, Gates and Ballmer decided to front five people themselves. They asked their own counsel—a Seattle attorney whose services Microsoft had used before—to attend the meeting, along with two other Microsoft employees. Allen, as usual, stayed in the background. “We got five people in the room,” said Ballmer. “That was a key thing.”

At the outset, IBM’s head of corporate relations explained why he had come along. It was because “this is the most unusual thing the corporation has ever done.” Gates thought it was about the weirdest thing Microsoft had ever been through, too. Once again, Gates, Ballmer, and the other Microsoft attendees had to sign a legal document, this time stipulating that they would protect in confidence anything they viewed at the meeting. Then they saw the plans for Project Chess. IBM was going to build a personal computer.

Gates looked at the design and questioned the IBM people across the table. It bothered him that the plans made no mention of using a 16-bit processor. He explained that a 16-bit design would enable him to give them superior software—assuming they wanted Microsoft’s. He was emphatic and enthusiastic and probably didn’t express himself with the reserve they were used to. But IBM listened.

IBM did want Microsoft’s languages. On that August day in 1980, Gates signed a consulting agreement with IBM to write a report explaining how Microsoft could work with IBM. The report was also to suggest hardware and Gates’s proposed use of it.

The IBM representatives added that they had heard about a popular operating system called CP/M. Could Gates sell that to them as well? Gates patiently explained that he didn’t own CP/M, but that he would be happy to phone Gary Kildall and help arrange a meeting. Gates later said that he called Kildall and told him that these were “important customers” and to “treat them right.” He handed the phone over to the IBM representative, who made an appointment to visit Digital Research that week.

When Gary Went Flying

What ensued has become the material of personal-computer legend. Instead of landing a contract with IBM, “Gary went flying,” Gates recounted, a story that became well known in the industry. Kildall disputed Gates’s recollection. He denied that he was out flying for fun while the IBM representatives cooled their heels. “I was out doing business. I used to fly a lot for pleasure, but after a while you get tired of boring holes in the sky.” He was back in time for his scheduled meeting with IBM.

That morning, however, while Kildall was airborne, IBM met with Kildall’s wife Dorothy McEwen. Dorothy handled Digital Research’s accounts with hardware distributors. The nondisclosure agreement that the IBM visitors asked her to sign troubled her. She felt that it jeopardized Digital Research’s control of its software. According to Gary, she stalled until she could get hold of Gerry Davis, the company’s lawyer. That afternoon Gary arrived on schedule, and along with Dorothy and Gerry Davis, he met with IBM’s representatives. Kildall signed the nondisclosure agreement and heard IBM’s plans. When it came to the operating system, though, they had an impasse. IBM wanted to buy CP/M outright for $250,000; Kildall was willing to license it to them at the usual $10 per-copy rate. IBM left with promises to talk further, but without having signed an agreement for CP/M.

They immediately turned to Microsoft. Gates required no prodding. Once IBM agreed to use a 16-bit processor, Gates realized that CP/M was not critical for their new machine because applications written for CP/M were not designed to take advantage of the power of 16 bits. Kildall had seen the new Intel processors, too, and was planning to enhance CP/M to do just that. But it made just as much sense, Gates told IBM, to use a different operating system instead.

Where that operating system would come from was a good question, until Paul Allen thought of Tim Paterson at Seattle Computer Products. Paterson’s company had already developed an operating system, 86-DOS, for the 8086, and Allen told him that Microsoft wanted it.

Three Months Behind Schedule Before We Started

At the end of September, Gates, Ballmer, and a colleague took a redeye flight to deliver a report. They assumed it would determine whether they got the IBM personal-computer project. They nervously finished collating, proofreading, and revising the document on the plane. Kay Nishi, a globetrotting Japanese entrepreneur and computer-magazine publisher who also worked for Microsoft, had written part of the report in “Nishi English,” which, according to Ballmer, “always needs editing.” The report proposed that Microsoft convert 86-DOS to run on IBM’s machine. After the sleepless flight, Gates and Ballmer were running on adrenaline and ambition alone. As they drove from the Miami airport to Boca Raton, Gates suddenly panicked. He had forgotten a tie. Already late, they swung their rental car into the parking lot of a department store and waited for it to open. Gates rushed in and bought a tie.

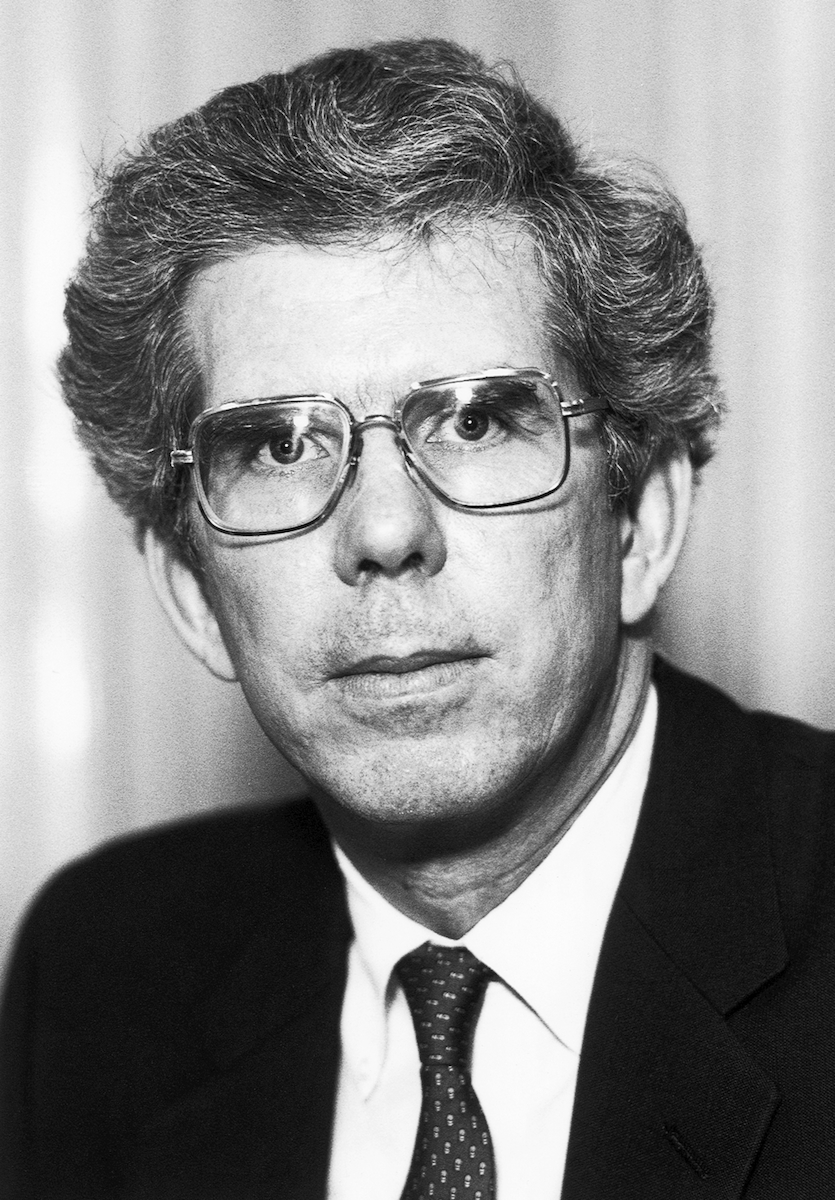

Figure 86. Phil Estridge Estridge headed the IBM PC project in the 1980s. (Courtesy of IBM Archives)

When they finally met with the IBM representatives, they learned that IBM wanted to finish the personal-computer project in a hurry—within a year. It had created a team of 12 to avoid the kind of corporate bottlenecks that can drag a project on for years—three and one-half for the Xerox Star, four for the HP-85. IBM president Frank Cary dealt roughly with all internal politics that could cause delays. Throughout the morning, Gates answered dozens of queries from members of IBM’s project team. “They pelted us with questions,” said Ballmer. “Bill was on the firing line.”

By lunchtime, Gates was fairly confident Microsoft would get the contract. Philip Estridge, who was the project head, an IBM vice president, and an owner of an Apple II, told Gates that when John Opel, IBM’s new chairperson, heard that Microsoft might be involved in the effort he said, “Oh, is that Mary Gates’s boy’s company?” Opel had served with Gates’s mother on the board of directors of the United Way. Gates believed that connection helped him get the contract with IBM, which was finally signed in November 1980.

Microsoft first had to set up a workplace for the project, a more difficult task than might be imagined. IBM wasn’t just any company. It treasured secrecy and imposed the strictest security requirements. Gates and Ballmer decided on a small room in the middle of their offices in the old National Bank building in downtown Seattle. IBM sent its own file locks, and when Gates had trouble installing them, IBM sent its own locksmith. The room had no windows and no ventilation, and IBM required that the door be kept constantly closed. Sometimes the temperature inside exceeded 100 degrees. IBM conducted several security checks to make sure Microsoft followed orders. Once the IBM operative found the secret room wide open and a chassis from a prototype machine standing outside it. Microsoft wasn’t used to dealing with this kind of strictness.

But Microsoft learned. To speed communication between Microsoft and IBM, a sophisticated (for those times) electronic mail system was set up, which sent messages instantly back and forth between a computer in Boca Raton and one in Seattle. Gates also made frequent trips to Boca Raton.

The schedule was grueling. The software had to be completed by March 1981. IBM’s project managers showed Gates timetables and more timetables, all of which “basically proved we were three months behind schedule before we started,” Gates said.

The first order of business was the operating system. Paterson’s 86-DOS operating system was a close but crude imitation of CP/M. It needed a lot of work to make it fit the bill for the IBM job. Gates brought Paterson in to work on adapting his operating system. The operating-system APIs, in particular, had to be completed as soon as possible.

APIs are application programming interfaces. They specify how application programs, like word processors, interface with the operating system. Despite the generally tight security surrounding the PC, developers writing application programs for the IBM machine had to have the APIs to do their work. That provided a crack in the security through which Gary Kildall managed to see, before the machine was released, what Microsoft’s operating system was like.

When he saw the APIs, Kildall realized just how close to his CP/M the new IBM/Microsoft operating system was. He threatened to sue IBM. “I told them that they wouldn’t have proceeded down that path if they knew [the IBM operating system] was that closely patterned after mine. They didn’t realize that CP/M was something owned by people.” IBM met with him and agreed to offer the 16-bit version of CP/M as well as Microsoft’s operating system for their PC. Kildall, in return, agreed not to sue. IBM said that it couldn’t set a price, though, because that would be a violation of antitrust laws.

When Gates heard about IBM’s dealing with Digital Research, he complained, but IBM reassured him that Microsoft’s DOS was its “strategic operating system.” It would turn out that Gates had nothing to worry about. Kildall’s operating system would never be given a chance to compete with Microsoft’s.

Meanwhile Gates took charge of converting Microsoft BASIC, the warhorse originally written for the old Altair, to the IBM computer. He worked on it with Paul Allen and Neil Konzen, another Microsoft employee. Six years before, Allen, as MITS software director, had nagged Gates to do the Altair disk code and the teenaged Gates had procrastinated. Now Gates was doing the nagging and Allen did most of the work. Other Microsoft programmers labored on the various language-conversion projects.

Gates was feeling the pressure from IBM, and he passed it on to his employees. Some of them were used to spending winter weekends as ski instructors—but not that winter. “Nobody went skiing,” said Gates. When some of them wanted to fly to Florida to watch the launch of the space shuttle, Gates was unsympathetic. But when they insisted, he said that they could go if they completed a set amount of work beforehand. The programmers spent five days straight at Microsoft, even sleeping there, in order to meet his demands. Allen remembers programming until 4 A.M. when Charles Simonyi, formerly of Xerox PARC, walked in and declared that they were flying down to Florida for the launch that morning. Allen protested. He wanted to continue his work. Simonyi dissuaded the exhausted programmer, and they were on the plane a few hours later.

Open Architecture

Gates discussed the design of the new machine with IBM continually, usually with Estridge. He pointed out that the open architecture of the Apple computer had contributed immeasurably to its success. Gates had reason to appreciate openness because the SoftCard, Microsoft’s only hardware product, was a cornerstone of the corporation. Because Estridge owned an Apple II, he had leaned toward an open architecture at the outset. With Gates’s encouragement, IBM defied its tradition of secret design specifications and turned its first personal computer into an open system.

This was an extraordinary move for IBM, the most aloof and proprietary of all computer companies. It was deliberately inviting the “parasites” that Ed Roberts had condemned. IBM would use standard parts and design patterns created by kids in garages, and it would encourage more contributions from them. It was shrugging off the tailored tux to don the ready-to-wear clothes of the hobbyists and hackers.

Gates especially understood the open-system issue from MITS’s experience. Ed Roberts had accidentally created an open system in 1974 by making the Altair a bus-based machine. Other manufacturers could, and did, produce circuit boards for the Altair’s S-100 bus, and an entire S-100 industry developed, to Roberts’s dismay. When Roberts tried to hide the bus’s details, the industry effectively took the bus away from him, redefining it to standard specifications.

Gates was intent on making Microsoft’s operating system, now called MS-DOS (really PC-DOS for IBM but MS-DOS for every other customer), the industry’s standard operating system. He abandoned the symbiotic relationship he had once enjoyed with Digital Research whereby Digital Research was the operating system firm and Microsoft did languages. Gates made a strong and convincing case to IBM for an open operating system, too. The IBM people in charge of the PC were receptive, but openness was not an IBM hallmark. The benefits took some explaining. If people knew the details of the operating system, they could develop software for it more easily, and VisiCalc had shown that good third-party software can help sell a machine. He may have had more practical considerations in mind, however. Having broken into mainframe operating systems when he was 14, having seen his original Altair BASIC become an industry standard through theft, Gates may simply have found it wiser to give away what would otherwise be preempted.

The operating system was also open in another way. Gates managed to get IBM to agree to let Microsoft sell its operating system to other hardware manufacturers. IBM didn’t understand what a wealth-creation machine they were handing to Bill Gates.

Although pressure to finish the software was extreme, Gates was confident in his ability and the capability of his company, which was glittering with programming talent. But he had one fear that he could not overcome. It concerned him even more than the deadline, and it haunted him right up to the announcement of the IBM computer: would IBM cancel the project?

They were not really working with IBM, after all. They were working with a division of IBM, a maverick division on a short tether. There was no telling when IBM might pull in the rope. IBM was a Goliath with many, many projects. Only a small percentage of the research and development work done at IBM ever appeared as finished projects. What other secret IBM personal-computer projects might be proceeding in parallel with Chess he didn’t know and would probably never know. “They seriously talked about canceling the project up until the last minute,” said Gates, “and we had put so many of the company’s resources into the thing.”

Gates was under strain, and any talk of cancellation upset him. He worried about the speculative stories increasingly appearing in the press about an IBM personal computer. Some were quite precise. Would IBM question his company’s compliance with its security requirements? When an article in the June 8, 1981, issue of InfoWorld accurately described four months early the details of the IBM machine, including the decision to develop a new operating system, Gates panicked. He called the magazine’s editor to protest the publication of “rumors.”

When IBM came out with its personal computer, fortunes would be won and lost. Bill Gates wanted to be sure nothing prevented Microsoft from being among the winners.

The IBM Personal Computer

When, on August 12, 1981, IBM announced its first personal computer, it radically and irrevocably changed the world for microcomputer makers, software developers, retailers, and the rapidly growing market of microcomputer buyers.

Figure 87. The original IBM PC In 1981 IBM’s entry into the field of personal computers legitimized the field and changed it fundamentally. (Courtesy of IBM Archives)

In the 1960s, there was a saying among mainframe-computer companies that IBM was not the competition; it was The Environment. Whole segments of the industry, known collectively as the plug-compatibles, grew up around IBM products, and their prosperity depended on IBM’s prosperity. To the plug-compatibles, the cryptic numbers by which IBM identified its products, like the 1401 or the legendary 360, were not the trademarks of a competitor, but familiar features of the terrain, like mountains and seas. When IBM brought out a personal computer, it too had one of those product numbers. But the IBM marketing people knew that they were dealing with a new kind of customer and that a number might not convey the right message. It isn’t hard to guess what IBM thought the right message was. By naming its machine the Personal Computer, it suggested this device was the only personal computer. The machine quickly became called the IBM PC, or simply the PC.

The IBM PC itself was almost conventional from the standpoint of the industry at the time. Sol and Osborne inventor Lee Felsenstein got his hands on one of the first delivered IBM PCs and opened it up at a Homebrew Computer Club meeting.

“I was surprised to find chips in there that I recognized,” he said. “There weren’t any chips that I didn’t recognize. My experience with IBM so far was that when you find IBM parts in a junk box, you forget about them because they’re all little custom jobs and you can’t find any data about them. IBM is off in a world of its own. But, in this case, they were building with parts that mortals could get.”

The machine used an 8088 processor, which, although it was not the premier chip then available, put the IBM PC a notch above any other machine then sold. The PC impressed Felsenstein—not technologically, but politically. He liked to see IBM admitting that it needed other people. The open bus structure and thorough, readable documentation said as much. “But the major surprise was that they were using chips from Earth and not from IBM. I thought, ‘They’re doing things our way.’”

In addition to operating systems and languages, IBM offered a number of applications for the PC that were sold separately. Surprisingly, IBM had developed none of them. Showing that it had learned from Apple, IBM offered the ubiquitous VisiCalc spreadsheet (Lotus 1-2-3 would come later and would become must-have software for business), the well-known series of business programs from Peachtree Software, and a word processor called EasyWriter from Information Unlimited Software (IUS).

WordStar, from Seymour Rubinstein’s MicroPro, was the leading word-processing program, and IBM had wanted it. But Rubinstein, like the Kildalls, balked at accepting IBM’s terms. They wanted MicroPro to convert WordStar to run on the IBM PC and then turn the product over to IBM, Rubinstein said. “They said I could build my own program after that, but I’d have to not do it the same way. They were setting themselves up to sue me later. They were going to grab control of my product. I had something to protect, so I didn’t do the deal. I tried to negotiate a different deal, but they wouldn’t.” IBM turned to IUS.

Captain Crunch and EasyWriter

The IUS deal may have been the ultimate culture shock for the IBM people. They had designed their machine with non-IBM components. They had released to the general public the sort of information they had always kept secret. They had bought an operating system instead of writing it; they had done and dealt with things that had always been utterly beyond IBM’s pale. But they hadn’t bargained for John Draper.

IUS was a small Marin County software firm with a word processor called EasyWriter. IBM had approached IUS about EasyWriter, and Larry Weiss of IUS contacted EasyWriter’s author, John Draper, alias the notorious phone phreak Captain Crunch, from whom Woz and Jobs had learned how to build blue boxes.

Draper recalled, “Eaglebeak [Weiss] comes to me and he says, ‘John, I got this deal that you’re not going to believe, but I can’t tell you anything about it.’ And then we had this meeting at IUS. There were these people in pinstripes and me looking like me. This was the time that I realized we were dealing with IBM. I had to sign these things saying that I wasn’t going to be discussing any technical information. I wasn’t even supposed to disclose that I was dealing with IBM. They were coming out with a home computer and Eaglebeak said something to me about putting EasyWriter on it.”

Draper had written EasyWriter years before out of frustration because the Apple had no satisfactory word processor and he couldn’t afford an S-100 system on which he could run Michael Shrayer’s Electric Pencil. Draper liked Electric Pencil, the only word processor he’d seen, so he fashioned his own after it. Demonstrating it at the fourth West Coast Computer Faire, he ran into Bill Baker, a transplanted Midwesterner who had started IUS, and Baker agreed to sell EasyWriter for him. All that had led to this: Captain Crunch sitting down with IBM.

IBM gave IUS and Draper six months to convert EasyWriter to run on the PC, and Draper went right to work. “In order to keep from slipping and talking about IBM, we called it Project Commodore,” Draper recalled. Soon, Baker was irritating Draper. “Baker comes down on me for not working 8 to 5, and that’s bullshit. Look, man, I don’t operate in that style. I operate in a creative environment. I don’t go by the clock. I go by the way my mind works.” Then IBM made changes in the hardware that Draper had to incorporate. The six months passed and the release program wasn’t done. Draper found himself pressured to say that an earlier but completed version was adequate and that it could be released with the machine. With grave reservations he finally did so, and IBM’s machine was sold with Captain Crunch’s word processor. The program did not receive rave reviews. IBM later offered free updates to the program.

A word processor was sober software, no matter who wrote it, but at the last minute IBM decided to add a computer game to its series of optional programs. Toward the end of the press release announcing the PC, the company declared, “Microsoft Adventure brings players into a fantasy world of caves and treasures.” Corporate data-processing managers around the country read the ad and thought, “This is IBM?”

Welcome, IBM

The PC’s unveiling received wide play in the national press. It was by far the least expensive machine IBM had ever sold. IBM realized that the personal computer was a retail item that consumers would buy in retail computer stores and could not, therefore, be marketed by its sales force. The company again departed from tradition and arranged to sell its PC through the largest and most popular computer retail chain at the time, the IMSAI spin-off ComputerLand. This was a much bigger departure for IBM than it had been for Xerox, but it was a no-brainer for ComputerLand. They knew the value of the IBM logo. IBM didn’t stop there; it also announced plans to sell the PC in department stores, just like any appliance.

Wherever it was sold, the purchaser had a choice of operating systems: PC-DOS for $40 or CP/M-86 for $240. If it was a joke, Gary Kildall wasn’t laughing.

Software companies quickly began writing programs for PC-DOS. Hardware firms also developed products for the PC. Because PC sales started fast and continued to increase, these companies were easily convinced that PC-based products would find a market. In turn, the add-on products themselves spurred PC sales because they increased the utility of the machine. IBM’s open-system decision was now paying dividends, for IBM and a new generation of plug-compatible companies.

Apple Computer was not surprised by the IBM announcement, as it had predicted an IBM microcomputer several years earlier. Steve Jobs claimed that Apple’s only worry was that IBM might offer a machine with highly advanced technology. Like Felsenstein, he was relieved that IBM was using a nonproprietary processor and an accessible architecture. Apple responded publicly to the PC announcement by asserting that this would actually help Apple because IBM publicity would cause more people to buy personal computers.

The world’s largest computer company had endorsed the personal computer as a viable commercial product. Although innovative hobbyists and small companies had founded the industry, only IBM could bring the product fully into the public eye. "Welcome, IBM. Seriously," Apple said in a full-page advertisement in The Wall Street Journal. “Welcome to the most exciting and important marketplace since the computer revolution began 35 years ago.… We look forward to responsible competition in the massive effort to distribute this American technology to the world.”

IBM’s endorsement certainly did increase demand for personal computers. Many businesses, small and large, balked at the idea of buying a personal computer. Many seriously wondered why IBM wasn’t working in that area. Now IBM had said it was all right. They could buy a personal computer. Between August and December 1981, IBM shipped 13,000 PCs. Over the next two years, it would sell 40 times that number.

The early microcomputers had been designed in the absence of software. When CP/M and its overlayer of application software became popular, hardware designers built machines that would run those programs. Similarly, the success of the IBM Personal Computer caused programmers to write an array of software for its PC-DOS operating system—which, when licensing it to companies other than IBM, Microsoft called MS-DOS. New hardware manufacturers sprang up to introduce computers that could run the same programs as the IBM PC: “clones.” Some offered different capabilities than those of the IBM machine, like portability, additional memory, or superior graphics, and many were less expensive than the PC. But all served to ratify the PC operating system. And MS-DOS quickly became the standard operating system for 16-bit machines.

Microsoft benefited more than any other player, including IBM. Gates had encouraged IBM to use an open design and had managed to get a nonexclusive license for the operating system. The former ensured that there would be clones if other companies could get their hands on the operating system. The latter ensured that they could, and that they would pay Microsoft for it. And IBM’s pricing strategy ensured that Microsoft’s operating system would be the only one that mattered.

Even DEC entered the fray a year later with a dual-processor computer called the Rainbow that could run both 8-bit software under CP/M and 16-bit software under CP/M-86 or MS-DOS.

All the companies in the industry had to cope with the imposing presence of IBM. ComputerLand was dropping the smaller manufacturers for IBM, and even Apple found that it had to respond to IBM’s incursion into the ComputerLand stores. Apple terminated its contract with ComputerLand’s central office where IBM was influential, and started dealing directly with the outlet franchise stores.

The Shakeout

It was the end of the beginning. A shakeout that had been only foreshadowed in the failures of MITS, IMSAI, and Processor Technology began to loom real in the eyes of the pioneering companies, and with more than 300 personal-computer companies in existence, many hobbyist-originated companies began to wonder if they would still be in business two years hence. IBM had forced even the big companies in the market to reappraise their situations.

Xerox, Don Massaro said, had carefully considered that IBM might produce a personal computer. “We did a worst-case scenario in getting approval for the [Xerox 820] program. We said, ‘What could IBM do? How could we not be successful in this marketplace?’ The scenario was that IBM would enter with a product that would make ours technically obsolete, they would sell it through dealers, and it would have an open operating system.” It seemed an unlikely prospect. “IBM had never done that, had never sold through dealers, and had certainly never had an open operating system. I thought IBM would have their own proprietary operating system for which they would write their own software, and that they would sell through their own stores.” Instead, Xerox’s worst fear came to life in painful detail, and “the whole world ran off in that direction. IBM just killed everybody.”

Not everybody. But the circle of attention had narrowed. There were now two personal-computer companies that everyone was watching: Apple and an IBM nobody knew; an IBM that had, in John Draper’s words, “discovered the Woz Principle” of the open system.

The presence of IBM and the other big companies shook the industry to its hobbyist roots. Tandy, with its own distribution channels, was only modestly affected. Commodore was doing all right concentrating on European sales and sales of low-cost home computers.

But the companies that had pioneered the personal computer began dropping out of the picture. The shakeout was in earnest. The resurrected IMSAI was one of the first companies to go. Todd Fischer and Nancy Freitas supplied the IMSAI computer that figured prominently in the popular movie War Games, and it was effectively the company’s last act. Shortly thereafter, Fischer and Freitas gave the pioneering microcomputer company a decent burial. (But not permanently: Fischer and Freitas would be selling IMSAI computers again in 1999, feeding a retrocomputing craze.)

By late 1983, even some of the most successful of the personal-computer and software companies to spring up out of the hobbyist movement were hurt. North Star, Vector Graphic, and Cromemco all felt the pinch. There were massive layoffs, and some companies turned to offshore manufacturing to stop leaking profits. Chuck Peddle, who had been responsible for the PET computer and had been active throughout the industry in semiconductor design at MOS Technologies and in computers at Commodore and briefly at Apple, was now running his own company, Victor, with a computer similar to IBM’s. In the face of the IBM challenge, Victor soon had to severely cut back its work force, hurt by softening sales. George Morrow’s company Microstuf considered a stock offering, but then withdrew the idea in response to IBM’s growing influence in the market.

On September 13, 1983, Osborne Computer Corporation declared bankruptcy amid a mountain of debt accumulated when it tried to catch up with Apple and IBM. Of all the company failures in the history of the personal-computer industry, none was more thoroughly analyzed. OCC had flown high and fast, and its fall was startling. At the height of their success, Osborne executives appeared on the television program 60 Minutes, predicting that they would soon be millionaires. They were on paper, but the company’s financial controls were so lax that the figures were meaningless. The media coverage of the company’s failure was intense, but the analyses were conflicting. Certainly there were problems with the hardware, but most companies have them and Osborne dealt with them. Osborne executives made serious mistakes in the timing of product announcements and the pricing of new products.

In May, Osborne had announced its Executive computer. Its improvements included a larger screen, but the company’s new “professional” management priced it at $2,495 and stopped selling the original product. Sales immediately declined. “If we had left the Osborne 1 on the market, management would have seen the mistake because it would have kept on selling,” said Michael McCarthy, a documentation writer at the firm. Instead, first-time buyers who liked the Osborne 1 for its packaging and price now looked elsewhere.

What seems clear is that Osborne grew so fast in its attempt to be one of the three major companies that Adam Osborne had predicted would dominate personal computing in a year or so, that its managers were unable to control it. As industry analyst John Dvorak put it, “The company grew from zilch to $100 million in less than two years. Who do you hire who has experience with growth like that? Nobody exists.” Osborne was just too successful for its own good.

The last chapter of the Osborne story had a bittersweet irony for the employees. Coming to work one day, they were instructed to leave the premises. Money owed them was not paid. Security guards were posted at the doors to ensure that they took no Osborne property with them. But someone had failed to inform the guards that the company made portable computers, and the employees walked out carrying Osborne’s inventory with them.

Others fell under IBM’s shadow. Small software companies like EduWare and Lightning Software allowed themselves to be bought by larger ones, and all software companies learned to think of first doing “the IBM version” of any new software product. Even major corporations adjusted their behavior. Atari and Texas Instruments swallowed millions in losses in their attempts to win their way into the personal-computer market through low-cost home machines. Atari suffered deep wounds. And although TI had more of its low-cost TI-99/4 computers in homes than almost any other computer, it announced in the fall of 1983 that it was cutting its losses and getting out of personal-computer manufacturing.

IBM’s entry also affected the magazines, shows, and stores. David Bunnell, who had left MITS to start Personal Computing magazine, responded to IBM’s arrival by coming out with PC Magazine, a thick publication directed at users of the IBM machine. Soon major publishers were fighting over Bunnell’s magazine. Wayne Green, having built Kilobaud into an empire of computer magazines by 1983, sold the lot to an East Coast conglomerate. Art Salsberg and Les Solomon rode out Popular Electronics’s transformation into Computers and Electronics. Jim Warren started an IBM PC Faire in late 1983 and then sold his show-sponsoring company, Computer Faire, to publishing house Prentice Hall, claiming that the business was too big for him to manage. ComputerLand and the independent computer stores found themselves competing with Sears and Macy’s as IBM opened new channels of distribution for personal computers.

Late in 1983, IBM announced its second personal computer. Dubbed the PCjr, the machine offered little technological innovation. Perhaps to prevent business users from buying the new and less expensive machine in place of the PC, IBM equipped the PCjr with a poor-quality “Chicklet” keyboard, a style of keyboard unsuited to serious, prolonged use. Despite the PCjr’s unimpressive technological design and chilly reception, by announcing a second personal computer, IBM demonstrated that it recognized a broad, largely untapped market for home computers. IBM intended to be a dominant force in that market, too.

Apple, in preparation for its inevitable toe-to-toe battle with IBM, made several significant moves. In 1983, the firm hired a new president, former Pepsi-Cola executive John Sculley, to manage its underdog campaign against IBM.

That Apple, no longer the dominant company in an industry still in its infancy, could attract the heir apparent to the presidency of huge PepsiCo was a tribute to the persuasive powers of its cofounder, Steve Jobs. “You can stay and sell sugar water,” he told a vacillating Sculley, “or you can come with me and change the world.” Sculley came.

Then, in January 1984, Apple introduced its Macintosh computer.

Figure 88. The original Apple Macintosh It had 128K of memory. (Courtesy of Apple Computer Inc.)

IBM had chosen to emphasize its name—the best-known three letters in the computer industry. Apple decided to provide state-of-the-art technology. The Macintosh immediately received accolades for its impressive design, including highly developed software technology that used a mouse, an advanced graphical user interface, and a powerful 32-bit microprocessor in a lightweight package.

But while Apple delighted in portraying this situation as a confrontation between Big Brother and the unruly upstarts, Apple was no longer some hippie garage shop financed by pocket change and float. The computer industry was now big business, and Apple was a serious, well-funded company.

The money dealers had come to where the money was, and the financial success of the industry rooted in hobbydom severed the industry from its roots. But the computer-power-to-the-people spirit Lee Felsenstein and others had sought to foster had by no means disappeared. Even staunchly conservative IBM had bent to it in adopting an open architecture and an open operating system. IBM’s corporate policy in the 1950s and 1960s had often been to lease computers and to discourage sales. For the room-sized computers made then, this method was appropriate. With proprietary architectures and software, the power of the machines really belonged not to the people who used them, but to the companies that had built them.

But something had changed in this first personal-computer decade, and in 1984 it looked like the personal computer and all the growing power it harnessed belonged to the people.