Word of Mouth: The Clubs and Shows

The First Computer Faire was definitely a torn-T-shirt, computer-junkie crowd. It was a gas. We didn’t know what the hell we were doing. The exhibitors didn’t know what they were doing. The attendees didn’t know what to expect. But we pulled it off.

–Jim Warren, computer-industry pioneer

Computer clubs and shows were the public forums of the early micro world. They not only offered hobbyists an entree into an interesting social club, but also supplied otherwise-unobtainable news about product releases and industry innovations. The clubs provided ongoing support for hobbyists and featured free and wide-ranging discussions about products, which often led to the publication of another newsletter. The fairs were technology spectacles, and their carnival atmosphere ignited each attendee’s enthusiasm for the growing field. They also gave hobbyists the opportunity to try out the latest novelties with their own hands.

Clubs

Homebrew Computer Club, with Lee Felsenstein presiding and other microcomputer pioneers in attendance, served as the prototype of the computer-enthusiast club. The group’s candid assessments of market offerings had an impact that reached far beyond the four walls of the club’s meeting room. Its influence reached user groups all over the country. When the magazines emerged, they sent reporters to cover the Homebrew meetings, spreading the club’s influence even farther. The Homebrew Computer Club’s opinion could be critical to a company’s success. Processor Technology, Apple, and Cromemco all profited from Homebrew endorsements. Many other corporations received less flattering appraisals, which were felt in their sales figures.

The first Homebrewers realized early on that they could affect the image and the future of the computer industry itself. Prior to 1975, computers were associated with technicians in lab coats—the “high priests” of the big machines—who would retire to an air-conditioned environment with a problem to solve and emerge sometime later with a printout. The Homebrew Computer Club helped replace that vision with one of rugged, if not ragged, individualism in which solo mental efforts could lead to multimillion-dollar companies. The Homebrewers felt that they had a duty to chart a road map of the future. The first edition of the club’s newsletter, issued in March 1975, predicted that home computers would perform tasks ranging from editing text and storing information to controlling household appliances and doing the housework (robotically) to instructing users and providing pleasant diversions.

Like Homebrew, the Amateur Computer Group of New Jersey (ACGNJ) became an arbiter and conduit for the new technology. For instance, the founders of Technical Design Labs of Trenton, New Jersey, started their company by selling used computer terminals at the ACGNJ meetings.

One early club that was run more like a professional organization than an informal group of hobbyists was the Boston Computer Society (BCS), even though its founder, Jonathan Rotenberg, was 13 when he started it. Rotenberg eventually developed BCS into a 7,000-member organization with 22 different committees, a resource center, and a lengthy list of industry and corporate sponsors. Rotenberg would later insist that BCS was a “users’ group, not a club.” BCS and the other users’ groups were computer clubs that had developed into something more. They served as informal think tanks, social groups, and arenas for the exchange of information. The clubs fostered a spirit of voluntarism and adherence to consumer advocacy that was carried over into the users’ groups. These groups worked to protect computer buyers to an extent that was unprecedented for any American industry. Committees worked diligently against shoddiness in manufacturing and deception in advertising. The clubs were responsible for directing the efforts of the free-spirited microcomputer manufacturers of the day. Without the feedback from the clubs, the early hobbyist-oriented microcomputers might never have developed into useful personal computers.

Shows

For the hobbyist shopping for hardware, nothing substituted for a hands-on demonstration of a new product. For that reason, and for that taste of “the future is now” that sends the imagination into orbit, hobbyists flocked to the computer shows.

Figure 48. West Coast Computer Faire Right from the start, the computer shows tapped the pent-up demand for personal computers and information about them. (Courtesy of David H. Ahl)

The first microcomputer fair to attract a sizable crowd was a single-company event. Early in 1976, David Bunnell of MITS began promoting the World Altair Computer Convention in Albuquerque in the MITS news organ Computer Notes. By the time the event took place in March, several hundred people turned out.

Among the speakers was Computer Lib author Ted Nelson, who delivered a scandalous and wildly entertaining speech on what he called “psycho-acoustic dildonics.” Lee Felsenstein (of Homebrew Computer Club, Community Memory project, and Processor Technology fame) was surprised some audience members didn’t drag Nelson off the stage during his carefully detailed explication of computer technology’s potential contribution to sex toys. After this off-the-wall presentation, Nelson talked to several people about setting up a computer store in the Chicago area. Nelson was a provocateur, but he understood that these computers were going to be big business.

MITS chief Ed Roberts planned the conference as a showcase for MITS and only MITS. He refused to give booth space to competitors such as Processor Technology. Proc Tech’s Lee Felsenstein and Bob Marsh were undaunted. Felsenstein suggested to Marsh that the two of them set up shop in a hotel room during the conference. "Great idea,” Marsh answered. They nabbed the penthouse suite and posted signs around the conference floor inviting people to drop by. They demonstrated Steve Dompier’s Target using the television set as their video display monitor. Because the Sol wasn’t ready, they had an Altair on hand. When Ed Roberts stopped by, it was the first time that he and Felsenstein had spoken since Lee criticized the Altair in Dr. Dobb’s Journal.

More shows soon followed in other places around the country. In May 1976, Sol Libes of ACGNJ put together the Trenton (New Jersey) Computer Festival, something of a hardware swap meet and discussion session. The fair pioneered the idea of an open computer conference that wasn’t tied to a single manufacturer. It also showed Californians that the microcomputer revolution was not confined to the West Coast. Featured speakers included premier hobbyist Hal Chamberlin from North Carolina, and David Ahl and Dr. Bob Suding of Denver. Ahl and Suding’s Digital Group had just received advance copies of the Z80 chip from Federico Faggin’s new semiconductor company, Zilog, and were raving about what could be done with this hot chip.

What started on the coasts soon spread across the country. In June 1976, a loosely organized group of hobbyists staged the first Midwest Area Computer Club conference. The inaugural event drew nearly 4,000 people. Midwest dealer Ray Borrill shared a booth with Processor Technology, which displayed its new Sol-20 computer. Borrill and Proc Tech sold thousands of dollars’ worth of parts and supplies, and because they hadn’t thought to bring along a cash box, money was stacked in piles on the table. By the end of the show, people were snapping up whatever was left in the booth, just to buy something. The computer-hobbyist fever was running high.

Then in August 1976, in Atlantic City, New Jersey, hobbyist John Dilks staged the Personal Computing Festival. This show was significant for being the first national computer show. This event helped popularize the term personal computing. Before that festival most people spoke in terms of hobby computing or microcomputing. Wayne Green’s Kilobaud magazine booth at the festival took in more than a thousand subscriptions. Peter Jennings bought the KIM-1 computer that he would later use to write Microchess. Other such shows were held in 1976, including events in Denver and Detroit.

But not in California. Dr. Dobb’s Journal editor Jim Warren had both an appreciation of these festive get-togethers and a gnawing sense that something was out of whack. “My myopic contention was that all of this good stuff was happening on the wrong coast,” he said. A week or two before the Atlantic City show, Warren commenced planning a show for the San Francisco Bay Area. He decided to call it a computer faire after the medieval summer spectacles in Elizabethan England. It was an apt name, he thought. A Renaissance faire celebrates the past; the computer faire would celebrate the future. In April 1977, Jim Warren staged the first West Coast Computer Faire.

When David Bunnell got wind of Warren’s plans, he contacted him on behalf of MITS. Bunnell said MITS was also planning a West Coast show, and suggested that the two merge their efforts and stage a conference sponsored by Personal Computing magazine. Warren would get 10 percent of the gate and profit further from his partner’s greater experience and professional acumen. Warren wasn’t at all comfortable with this proposal. He didn’t consider it appropriate that he, as editor of Dr. Dobb’s, be involved in a show sponsored by Personal Computing or any other magazine. He was also uneasy about the emphasis on money. “I wasn’t thinking about doing a big-bucks thing at all,” he recalled. “I just wanted to stage this event. I’d done the be-ins in the ’60s. I just wanted this [computer fair] stuff happening out here.”

Warren tried to reserve some space at Stanford University for his event but couldn’t get the dates he wanted. He then looked into the San Francisco Civic Auditorium. It would be a great spot for the event, he thought. It had excellent conference facilities and a splendid exhibition room. He asked how much it would cost. Rental was $1,200 per day. He was stunned.

Later that day, Warren got a bite to eat with Bob Albrecht at a restaurant called Pete’s Harbor. They did some figuring on a table napkin. If they could get at least 60 exhibitors, charge them around $300 each, and draw maybe six or seven thousand people, they could break even. What the hell, Warren thought, they could actually make money on the event. That’s the precise moment when he founded his company Computer Faire.

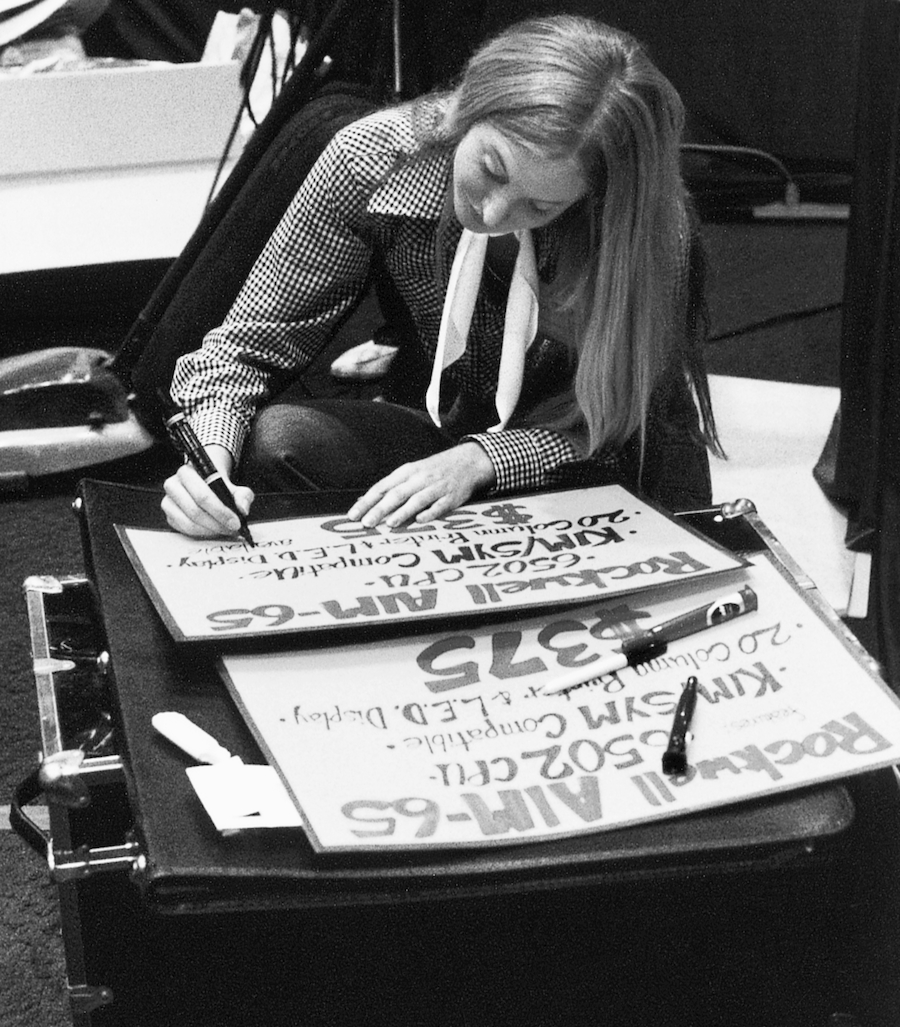

Figure 49. West Coast Computer Faire exhibitor An exhibitor getting ready for the first West Coast Computer Faire in 1977 (Courtesy of David H. Ahl)

As it turned out, Warren greatly underestimated the attendance figures. He had hoped to draw 7,000 to 10,000 people between Saturday and Sunday. Instead, almost 13,000 showed up. For several hours on Saturday morning, two lines of attendees stretched around one side of the auditorium and three lines stretched around the other side to the back of the building. It was a clear and windy day, and fairgoers stood in line chatting with each other. It took an hour to get through the door, but no one seemed to care. The fair had begun outside during the discussions among individuals who were equally rabid about computers.

Once inside, attendees found themselves in computer heaven. Rows and rows of festively decorated booths touted the latest advances in personal computing. An inquiring hobbyist could find him- or herself chatting up the very person who had designed some innovative product. Company presidents in T-shirts and blue jeans staffed a number of booths. The Apple II was unveiled in a large and rather attractive booth staffed by Steve Jobs, Mike Scott, and other Apple executives. Gordon Eubanks demonstrated his BASIC-E in a booth he shared with Gary Kildall. The Commodore PET was also introduced at the event.

Sphere had failed to rent booth space, but still made its presence known. The Sphere folks parked the Spheremobile, a 20-foot motor home modeled after MITS’s Blue Goose, out front and sent an employee to walk through the fair wearing a placard saying, “Come see the Sphere.” The excitement could be felt everywhere. “It was like a toy store at Christmas. It was mobbed,” said attendee Lyall Morrill. Among the many cosponsors were the Homebrew Computer Club, the Southern California Computer Society, PCC, and the Stanford Electrical Engineering Department. Science-fiction writer Frederick Pohl spoke, as did Ted Nelson, Lee Felsenstein, Carl Helmers, and David Ahl. Everyone agreed it was a gas.

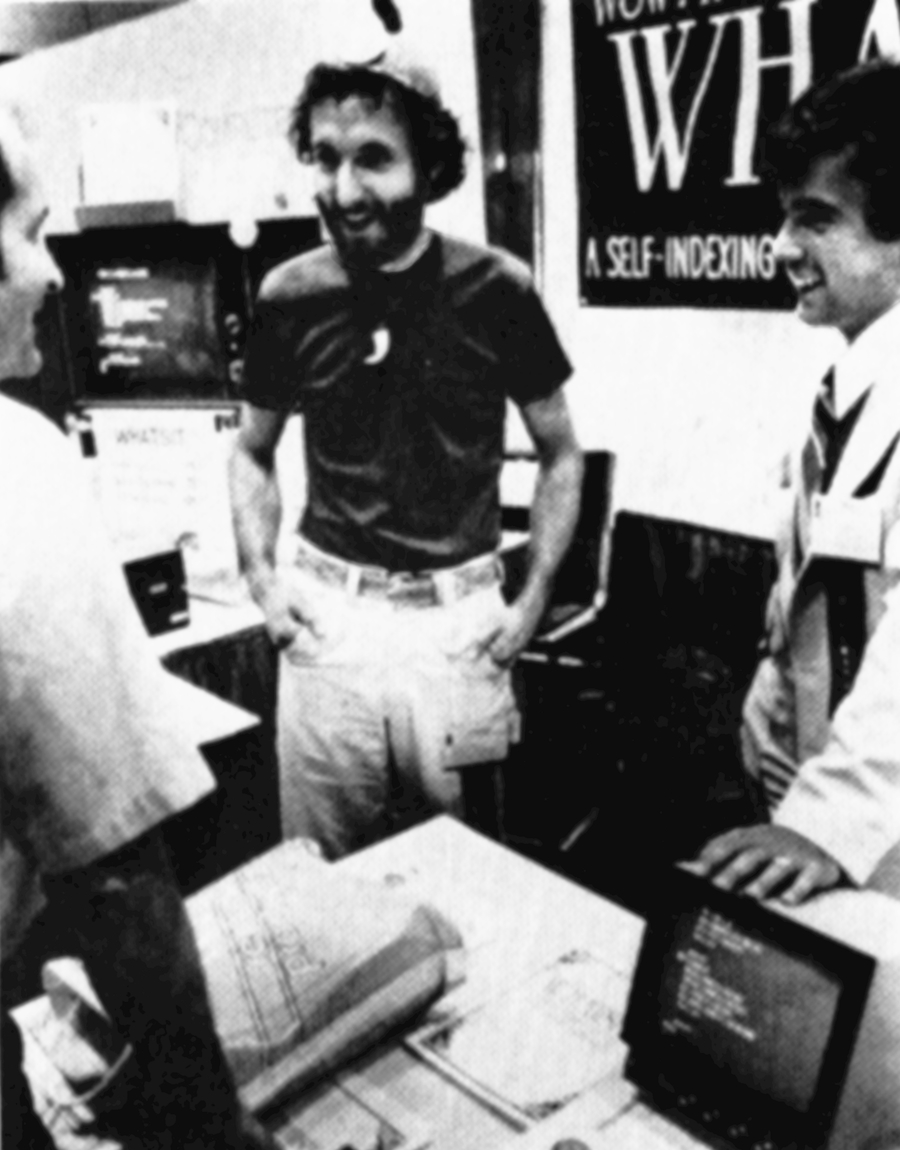

Figure 50. Lyall Morrill and Bill Baker Early software entrepreneurs Lyall Morrill (left) and Bill Baker talk with a customer at the second West Coast Computer Faire. (Courtesy of Paul Terrell)

Jim Warren spent most of the weekend in a whirlwind, racing around to smooth out little snafus. At subsequent faires, he saved time by dashing around the convention halls on roller skates. Even while attending to the administrative duties, Warren was as thrilled to be there as everyone else. “It was the excitement of turning all those people on,” he recalled. He felt proud of his accomplishment. The first West Coast Computer Faire was three to four times larger than any previous computer show. It also led to the first published proceedings of a personal-computer conference. Warren had made his contribution to the industry by staging this watershed event.

Before the first West Coast Computer Faire even opened, Warren had decided to stage a second one. It took place in March 1978, in San Jose, California. Exhibit space was sold out a month in advance. Lyall Morrill once again was on hand, but this time he represented his own software company, Computer Headware. “Either by the luck of the draw or the strange humor of Jim Warren, my booth was positioned next to the IBM booth,” he noted. The contrast between the two booths was striking. IBM had mounted a slick chrome booth staffed by men in business suits and polished dress shoes. The booth featured the IBM 5110, a relatively expensive desktop minicomputer that didn’t particularly impress the attendees.

Morrill, wearing a propeller-topped beanie, was showing off his software package, a simple database-management program called WHATSIT, a loose acronym for Wow! How’d All That Stuff Get In There? He had created his signs the night before with a felt-tip pen. Jim Warren enjoyed the IBM–Computer Headware juxtaposition so much that he had photos taken of Morrill socializing with the IBM staff.

IBM and Computer Headware’s sales results by the close of the faire were as far apart as their corporate style. IBM got just a few orders, whereas Morrill was besieged with them. Customers queued up at his booth, credit cards in hand, to buy his program.

The second West Coast Computer Faire was such a great success that Warren decided to do one every year. If, as Carl Helmers said, the magazines defined the microcomputer community, shows such as Warren’s gave the community a meeting place.