After Chapter 4, I hope you have gotten over your discomfort with the notion of “product,” because you’re going to have to get used to the idea.

Product is what you sell. If you don’t sell any products, then you won’t have any income and hence there will be no career. So make a choice: Get over your squeamishness or go and get a proper job.

We are now going to look at the business aspects of products and hence your career.

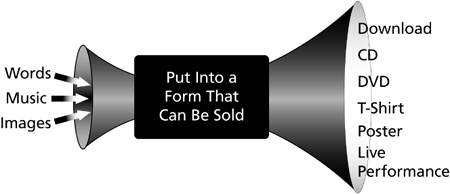

Before we go any further, let me explain what I am calling a product (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. The process of product creation takes something intangible (words, music, and so on) and converts it into a form that can be sold (such as a download, CD, or DVD).

In simplistic terms, a product is something you can sell (or sell advertising against), so a few chords and a line or two from a chorus don’t make a product (although they may be part of the product development process). However, more than simply being something that has the potential to be sold, a product is a freestanding item, tangible or intangible, that ideally can be sold again and again and again.

So for instance, the following are examples of products:

A download

A CD

A DVD

A T-shirt

A poster

A live performance

There is a strong argument that you could call a live performance a service rather than a product because you are selling entertainment (which could be deemed to be a service) to people. However, I don’t want there to be any confusion in terms between products and services, so I am calling everything a product. If it is something that you give to your fan base in exchange for money, then it is a product.

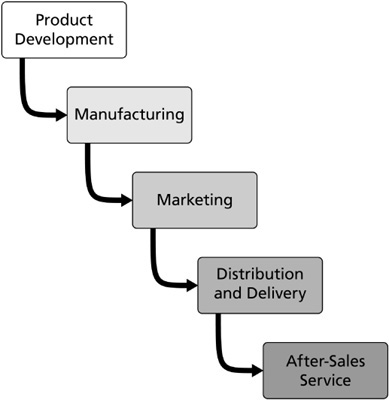

When you start thinking about products, you need to think about the process, from creating a product, to selling it, to providing after-sales service. Most products will follow a process that has the following steps (see Figure 5.2). For now, I want to briefly introduce these main steps—I will then go on and discuss them in greater detail.

The first stage of creating a product is the development stage. At this point, the product is conceived and researched. Only when you are sure that the idea is viable should the product be taken forward.

Part of the product development is obvious and natural—an example of this would be writing songs. However, other parts may be unnatural (or at least not something that you may have experienced before). For instance, you may not have familiarity with the process involved in creating a T-shirt.

The manufacturing stage is when the product is created. At this point you actually make something tangible, whether that is a recording of a song or a test of a T-shirt. This is the first chance to see, hear, and touch something real.

You will often also find that there are problems at the manufacturing stage. The band may not be performing as well as you had hoped in the studio, or the T-shirt may be of a substandard quality. This may be the only opportunity you get to ensure that the quality is everything you hoped for, so take the time to ensure that the quality is perfect.

In the marketing phase, you explicitly attempt to raise awareness of your product with your fan base and the wider public. Traditionally, this is when the act goes on the road, plays live shows, and makes as many TV/radio appearances as they can. For many musicians, the two hours on stage each night are the reason they got into the business—the remaining 22 hours of each day are mindless tedium (interspersed with a hunt for willing sexual partners).

There is no point in creating products unless you can get the product to purchasers—in other words, if you can’t find a way to get the product to a person willing to lay down cash (for instance, you can’t get a CD to someone), then there is no point in creating the product in the first place.

There is no art or craft in efficient delivery; it is pure administration. That being said, when it goes wrong, it is a nightmare for you and your fans, so it is well worth finding someone who can organize this aspect of your business.

Selling your product and getting it to the fan is not the end of the story. You’re going to need to respond to complaints. For instance, merchandise may not arrive, CDs may not play, or the booklet may be badly printed. Whatever the complaint and regardless of whether it’s your fault, you’ll be expected to ensure that these things are fixed, because ultimately a shoddy product directly translates into a bad reputation for you.

Now that we have agreed on what we are calling a product, what product are you going to sell to your fan base? This is where product development comes in.

You probably looked at the products I listed in the previous section and thought that you wanted to do all of them. (This is not unreasonable; most musicians do want to produce downloads, CDs, DVDs, T-shirts, posters, and live performances.) You probably also got lots of other ideas for products you would like to create.

Let’s look at some of the factors that should influence your choice of which products to develop.

Although it may seem like an odd consideration, the number of products you offer is an important issue.

You should aim to have a reasonably wide range of products so that you can offer something for most of your fan base. If you limit your product range, then you are limiting your potential income. If there is nothing more for people to buy—perhaps because they’ve already bought everything you have to offer—then they won’t give you any more of their money.

And while we’re talking about money, let me mention price—as in the price you charge for your product. I’ll talk about this subject in more detail later in this chapter, but for the moment, please remember that different people want to pay different amounts for what is apparently the same product—this is why people buy expensive cars that perform the same function as cheap cars. Taken to its extreme at the other end of the spectrum, some people will believe that the correct price for your content is zero. To address the differing attitudes to price, as well as a range of products, you need a range of prices (which I’ll come to later).

By contrast, if your product range is too broad, that will create other problems—for instance, if you are dealing with real products (such as CDs), you will have large amounts of stock to store, insure, and keep track of. Also, with a wide product range, you may end up spending more time on your products and less time on your music.

When you first start out, it will be quite easy to limit your product range because you will be starting from zero. Perhaps a bigger problem will be charging for products.

Only you can decide what is right for you in light of your fan base. To the extent that you are uncertain about the scope of your product range and the number of each product that you will stock (and you should be uncertain about developing any product for which you don’t have an order that has been paid for), then don’t be too ambitious: Start small and grow.

Now that you have an idea about some of the products you can develop, it’s probably a good idea to prioritize the development of these products. This will ensure that you have a steady flow of new products rather than everything arriving in one lump, and that you don’t spend all of your time thinking about products and none of your time making music.

Planning will also help you to think about future products. You may have just released your latest album, so it would seem a sensible approach to plan when the next album will be released, given that it may take a year from conception to release (and that’s presupposing that an album is right for you—for many acts, single songs are more appropriate). With a bit of planning, you can ensure that you get everything you want sorted out. For instance, with some planning you could find a time when the producer you’ve always wanted to work with is available.

As a first step in the planning process, split your ideas into two piles: those things you should do and those things you should think twice about.

The things that you might think about developing include:

Products you need because they define who and what you are. Two examples of products that define you are recorded tracks (available as downloads or CDs) and gigs. I can’t see many people existing as musicians without developing one or both of these.

Products that generate a healthy income and a profit. I will talk more about this issue under the section “The Cost of Developing Products,” later in this chapter.

Products that advertise you or raise your profile. A great example of this is T-shirts. Think about it: People will pay you money to advertise your brand on their body!

Then there are some things that you should think twice about (and then think again). As a start, this category will include products for which you need to carry a large stock, which have low margins, or which you just don’t understand.

So what products should you create? That depends on your fan base and what you actually do. If you are creating a product that your fan base wants to buy, then you won’t have to work hard to make sales, but you may have to work hard to ensure that your fan base knows about the availability of the product—especially if you don’t have a direct line of communication with your fan base.

By contrast, if you create a product that your audience doesn’t want, then you’re likely to have a lot of stock on your hands. Think about the notion of “want” in human terms, not just in relation to a general demographic. Ultimately, you should develop products you are passionate about—develop things that really matter to you and things that you care about. These are the items your fan base is far more likely to be interested in and will want to buy.

In this book I don’t offer you money, but I am trying to help you find a way to do what you love and to generate sufficient income to live. It is your career, and you need to feel good about yourself. If you develop products that you are truly passionate about and that you truly believe are good, then it doesn’t matter whether you sell 1,000 or 10 million (or just a few to your family and friends)—you will still believe you have a good product and will feel proud. And you will know that you haven’t ripped off your fan base with second-rate tat.

One of the biggest difficulties in developing a new product is knowing what your fan base wants and what they will buy. It’s pointless to develop a new product if no one is ever going to buy it.

One way to find out what products would interest your fan base is to carry out some research—in other words, ask people directly. This can be useful to a certain extent; however, one of the downsides of market research is that people aren’t always straightforward. If you ask people whether they would buy a certain product, they may say they would. However, this doesn’t mean that they will buy the product.

For instance, the person you surveyed might have been willing to buy when surveyed, but may have run out of money by the time the product is available. Alternatively, people may change their minds, or the product might not be what they expected from the description given when they were surveyed.

Whatever the reason, they won’t buy.

And just to be clear here, I’m not suggesting that if you’re a death metal band, you should ask whether your audience wants you to create bubblegum pop. What I’m looking at here is focusing your options.

A better way to know what the fan base might want is to know the fan base. If you get to know your fan base over a sustained period of time, and you have conversations with individuals (two-way conversations, asking questions and listening), you may get a better feel for what they want than you would get if you followed the survey approach. However, you still will not get a perfect idea.

You will only truly know what sells once it has sold.

Research can be helpful, and I always suggest that you get as close as possible to your fan base; however, if you want to know whether something sells, then the best course is to try selling it. If you start small, so that you don’t take too much of a loss (perhaps only releasing a product through an on-demand service), you will be able to gauge interest. Then, on the basis of actual sales figures, you can grow your product.

So for instance, you may know that your fans will buy T-shirts, but you don’t know whether they will buy baseball caps. You could set up a baseball cap with an on-demand service and order, say, 50 caps to try to sell at gigs. If they don’t sell, then you won’t have lost too much. However, if they do sell, then you could look into having them produced at a lower cost (in other words, at a cost that may allow you to generate some profits).

And of course, your main product—your music—doesn’t really lend itself to market testing!

There are several elements in the strategy I am setting out in this book. For the moment, I want to look at two pieces: the direct relationship with your fan base and making excellent music. By bringing these two focal points together, you are getting close to developing a product that will sell itself. This is a good thing, because as you will have noticed, the strategy in this book does not rely on extensive advertising and hard selling. Instead, it relies on people wanting to buy.

Before I look at other products, let me look at your music products and take the example of producing a CD.

There are many elements that affect the overall quality of a CD, including:

The songs. You need well-written, properly structured songs with instantly memorable tunes and lyrics to draw in the listener immediately. Songwriting is an art and a craft, and you should continually seek to improve your writing ability, whether through courses, a songwriting consultant, reading about other songwriters, continuing to practice your skill, or working with other writers.

The songs should be well performed. There is no excuse for an average or lackluster performance. Remember, your recording could be available in 10, 20, 30, 40, or more years’ time, and you could still be receiving income over this period. Surely, for a work that will have that longevity, the extra take just to nail the track is worthwhile.

When it comes to performance, are all the musicians as good as they could be? Are you recording with a singer who has never had a singing lesson in her life? Does the bassist have trouble with the notion of 4/4 time? Does the guitarist keep old, dull strings on his guitar? You need to do anything and everything you can to improve the quality of your product before you sign off on a recording.

The songs need to be well recorded. This doesn’t mean that you need an expensive recording studio; it just means that you need to ensure the absolute highest audio fidelity—and don’t kid yourself that your ropey old computer will do. Equally, don’t kid yourself that a shiny new computer will make you sound great when there are more fundamental problems (such as lack of talent, a poor recording room, or similar factors).

I also have to question your commitment to creating a product of the very highest quality if you’re not going into a studio with the best producer you can find (and, of course, afford). You may be good, but ask yourself how many hit record there have been over the last few years that haven’t had a top-flight producer? Some, but maybe not that many who have gone on to have a lasting career. You really need to find a producer who will ensure that you sound like a bunch of slick professionals and not like a group of highly talented amateurs who don’t quite make the grade.

Once the tracks have been recorded, they need to be mixed and mastered. You may be able to record yourself. You may have even bluffed the production bit. However, before you go any further, ask yourself whether you have the talent to mix and master your material. I’m sure there must be some artists somewhere who record, produce, mix, and master their own work, but I think these people are few and far between and may not sell huge numbers of records.

If you want the best product that you can have, then find the best mixer you can afford and find the best mastering engineer.

The final step (in this example) when the recording, mixing, and mastering has been completed is to get the CD pressed. All your hard work will be in vain if the reproduction, printing, and packing are not completed to the highest standard.

Although you may get each element right on its own, it is also fundamentally important that the elements work together. For instance, if you have the best producer, the best mixing engineer, and the best mastering engineer working on your project, then they all need to know what you want and expect. If each individual has his or her own separate vision of where your product is heading, then these individuals may work against each other. The producer may add lots of bass parts, the mixing engineer may feel that the bass end is too muddy, and the mastering engineer may feel the track lacks body, and so he boosts the middle of the audio frequency.

Someone needs to take hold of a project and ensure that all of the parties understand what you want. (When I say “you,” I mean you the client—the person who is paying everyone’s salaries.) If they then don’t do what they’re told, don’t pay them.

To succeed, your product must be of the very highest quality. You won’t sell just because you’ve sent an email to your fan base. You have to create something that your fan base wants to buy—this is very much the strategy of “build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door.” Remember, you are not stuffing your product down people’s throats with advertisements, so you need something that is really good in order to convert interest into sales (and quickly). If you create a stinker of a product, the word will spread very quickly.

I have discussed one particular musical product here (the production of a CD). The principle of producing the best product you can applies to any product, whether it is a gig or a mug. If you’re not selling top-of-the-line products, then life is going to be tough for you.

One of the biggest problems will be deciding when a product is ready to be released to the public.

For an artist signed to a major record label, the decision to release an album is usually fairly simple. If the producer says it’s ready, and the label thinks it’s ready, then it is ready, and the album (or whatever) will be released.

If you’re trying to release a product (any product, not just a CD) without having someone with that level of financial involvement, then you need to be really certain that you aren’t releasing your product too soon. When you think that you may be close to release, make sure you distance yourself from the product (as far as you can) in order to stay as objective as possible.

Also, again to the extent possible, consider other people’s opinions. In particular, if you have paid someone to be involved with a product (for instance, a producer), and her reputation is on the line too, then make sure she believes you are ready to release.

Products get renewed: In other words, production of old products ceases, and a new product comes in its place.

Outside of the music industry, product renewal comes in two forms:

Giving additional features to an existing product to make it more attractive

Launching a whole new product to replace an existing product that is withdrawn from the market

This sort of product renewal can be difficult in the music industry, so let’s look at the example of how the video-game industry renews some of its products:

To encourage new purchases of an existing game console, further titles can be released. This creates more reason to buy the console. In addition, giving away free games when a console is purchased lengthens the lifespan of the console by increasing demand.

To encourage renewal, a whole new console can be released that is incompatible with existing games. Of course, the stated reason for the incompatibility is to give new features.

The key difference between these two approaches is that with the first option you are getting more sales from the original product, so you are widening your user base. With the second approach, the existing user base is being asked to replace a product that has become obsolete (and all of the games for the obsolete product can be regarded as obsolete, too)—in other words, people are being asked to buy the product for a second (or third or fourth) time.

These sorts of practices do happen in the music industry. Here are a few examples:

Greatest-hits albums bring in new fans (and can sometimes sell to existing fans who want to own all of an artist’s catalogue).

Greatest-hits albums with new tracks bring in new fans and sell to existing fans who are keen to get the new tracks.

Remixed and remastered versions of old (usually classic) albums are intended to be sold to existing fans as an “upgrade” to their existing album.

Live albums sell the same songs to existing fans. The same principle applies for acoustic versions of existing songs.

Limited-edition merchandise, such as a tour T-shirt, becomes available. Because availability of the T-shirt is limited to a certain timeframe, a new T-shirt can be sold when this one has become obsolete. Any piece of merchandise can easily be made into a limited-edition product that can then be replaced by new limited-edition products. Perhaps the most obvious limited-edition product (that will generate income every year) is a calendar.

The complete renewal of a product (such as the new video-game console) is a harder task to achieve. The music industry last did this very effectively when it made vinyl obsolete with the introduction of CDs. However, since then it has not managed to renew its products so well. That is not to say it hasn’t renewed—for instance, MP3s, remastered albums, and attempts at higher-quality audio (such as 5.1 mixes) have had some effect.

For your early products, just focus on getting a successful product launched and ensuring that you make a profit. Remember the possibilities of renewal, and don’t make any decisions that would make it harder for you to renew your products.

When you have a portfolio of products, then you can consider whether it is feasible to produce a version two or a version three of any products. Before you renew your products, consider two issues:

Will renewing the product make it easier to sell the renewed product? In other words, will the existing product already be recognized/established in the market? Alternatively, will it being renewable make it easier to reach a wider fan base?

Will renewing the product make it harder to sell in the market? Will the renewed product just be seen as a re-tread of a tired old product that should simply be dropped? Equally, will renewal tarnish your reputation?

Only you know how your fan base will react, and only you can decide upon the right course for your business.

I now want to focus on some of the logistics of product development. As I discussed earlier in this chapter, as a crude rule of thumb, the more products you can produce, the higher your income will be (within reason). However, to develop a high-quality product that will enhance your reputation and will sell, you need to invest a lot of time.

You need to balance these two competing interests to ensure that you have time to do what you love (make music) and generate sufficient income.

You need to take development time into account to organize your life. Historically, most artists follow a structure in which they record an album, release the album, and then tour to promote the album. The tour is usually booked before the album is finished, so a few months’ gap is left for overruns. If you don’t plan well enough, you could be touring before you have finished and released the album you are meant to be promoting.

Without wanting to belabor the point too much, remember that planning also takes time, so you should include an allowance for planning. (I know it sounds like planning how to plan, but it’s better to remember it than to get it all badly wrong.)

When you are planning a project, there are some activities that can happen only after something else has happened. For instance, you cannot mix a track until it has been recorded, and you can’t press a CD until the songs have been written.

Equally, there are plenty of activities that are not dependent on other activities. For instance, you don’t need to have completed the mix of an album to commission the artwork.

The key to successful planning is ensuring that you have a timescale for each part of the project and then recognizing which parts are dependent on a previous task having been completed and which tasks can be completed independently. Clearly, the tasks that are dependent on a previous task are the hardest to plan, particularly when you are trying to schedule several people together (such as a producer, a mixing engineer, and a mastering engineer).

Turning to focus on the logistics of product development, as a musician you know that there are no shortcuts when you create music. You cannot half-write a song and hope that you are inspired to write the remaining part when you get up on stage and start playing the song. If you’ve only half-written a song, you will find it is impossible to teach the rest of the band the song.

If you are a songwriter, you know that songs get written in many different ways. Sometimes inspiration comes to you, and the song writes itself in as long as it takes you to play it. Other times, you need to keep returning to a song over a long period of time, perhaps agonizing over one word or one note for several weeks. Maybe you write with a partner, or you and the whole band all get in the room and play. Everyone throws in lines and melodies, and together you create perfection that could not be created by any of you individually.

You also know there is no right or wrong way to write a song, although it often feels as if you are using only the wrong ways. This is the nature of the creative process, and how you create is up to you.

However, although I do not wish to put any constraints on your creativity, I would like to make a few suggestions:

First, understand your creative process. If you are a songwriter and you can write 10 hit songs in an afternoon, that’s great. However, if, like normal people, it takes you a lot longer to write songs—perhaps a couple of days, or maybe each song is written over several weeks—that’s fine. Just make sure you have factored the writing into the product-development process.

Equally, if you ask someone else to get creative on your behalf—for instance, you might ask someone to create some artwork for a poster—then try to understand the person’s creative process and the timescales to which he works.

In the 1950s and 1960s, whole albums could be recorded in a matter of hours. I think the Beatles’ first album was recorded in three hours. Those days are gone—I don’t think you could get a kick drum set up in less than three hours these days.

You should always ensure that there is sufficient time to record, but you may want to constrain this time if you are working to a tight budget. It is very easy to sit around and say, “We should be able to record this whole album in a few days, as long as we have rehearsed enough.” However, it will always take longer than you expect, especially if you are aiming to create the highest quality product. Unfortunately, the only way you will learn exactly how much time you need is to spend the time.

As well as understanding the creative process, develop a thorough understanding of all of the other aspects involved in making the product happen. Make sure you (or whoever is running the project) understand which function each person involved in the project fulfills and how much time her process will add to the project.

Product pricing is crucial. Charge too much, and no one will buy the product. Charge too little, and you won’t make a profit.

In the next section (“The Cost of Developing Products”), I will discuss the cost of developing products and the economics that determine when a product starts to make a profit (or, more importantly, the point at which a product ceases to make a loss).

Development costs will have a significant influence on pricing. However, there are many other influences—some are scientific, but most are less so. Perhaps the two most significant questions when it comes to pricing are:

What price will people pay? In other words, how much can you charge before people will refuse to buy your product? The secondary issue here is at what level your fans will think you are abusing their good nature and taking money straight out of their pockets. If you reach this price point, you will lose fans quickly.

What price will make the product sell? In other words, how low do you have to go to encourage sales? You should also remember that there is a point at which your product will look “bargain bin”—if you reach this, then you will lose credibility. You should also remember that rubbish never sells.

You might be thinking that you’ll set the price of each product according to the manufacturing costs, then add a bit for profit, and perhaps give the retailer some margin. This is admirable but probably rather naïve. As the next section about the cost of product development will demonstrate, it is difficult to know when a product will break even, and once you’ve broken even, what do you do then? Drop the price. Also, even if you price a product on the most reasonable basis, people will still feel ripped off.

People feel ripped off because they will ascribe a value to your product based on their own beliefs and values. In other words, they will value your product based on what they feel it is worth for them, not based on what you feel/know it is worth. It is for this reason that manufacturers apply differential pricing.

Let me give you an example of differential pricing from Apple. Take the iPad 2, and look at the price/features set out in Table 5.1. (Please note these are the UK prices quoted today on the Apple website, including VAT [value-added tax] but excluding any carrier costs associated with the wireless connection.)

Table 5.1. Apple iPad 2 Prices and Features

Model | Memory | Wireless | UK List Price |

|---|---|---|---|

iPad 2 | 16 GB | Wi-Fi only | £399 |

iPad 2 | 32 GB | Wi-Fi only | £479 |

iPad 2 | 64 GB | Wi-Fi only | £559 |

iPad 2 | 16 GB | Wi-Fi and 3G | £499 |

iPad 2 | 32 GB | Wi-Fi and 3G | £579 |

iPad 2 | 64 GB | Wi-Fi and 3G | £659 |

So, what does this show us? Well, first off, you will see there is a price range, from £399 to £659.

Is the most expensive model really worth £260 more than the cheapest model? That’s a 65 percent price increase.

Look at the factors affecting the price: memory and wireless connectivity. With either model, it costs £60 to increase the memory from 16 GB to 32 GB, and a further £80 to increase the memory from 32 GB to 64 GB (so you’re paying £3.75 per gigabyte and £2.50 per gigabyte, respectively, for the memory boost). You’re also paying £100 to have the option of 3G connectivity (before you pay any carrier charges).

So does it cost more to manufacture a model with more memory? Is the 3G wireless really that expensive? Are the higher-priced models a better value?

First, let me give you some price comparisons. If I wanted to buy a 16-GB SD memory card on Amazon, I could get one for £13.99, and a 32-GB SD memory card for £28.88. For the wireless difference, look at the Kindle, where the Kindle Wi-Fi costs £111 and the Wi-Fi/3G model costs £152. Now, of course, this is a slightly bogus comparison, but you see that others seem to think that memory and 3G wireless may cost less to add to a product.

Although these comparisons are interesting, let’s get back to the main point: Why the price differences?

The simple answer is because people will pay what they think the product is worth. If someone thinks that an iPad is worth £400, then they’ll buy the base model. If they think it’s worth £500, then they might by the Wi-Fi and 3G base model, or perhaps the Wi-Fi-only, 32-GB version. Sure, they might justify that they need the extra memory or the 3G connectivity, but at the end of the day, it all comes down to what they want to pay.

Whatever your perception, price is a matter of what people want to pay; it has virtually nothing to do with the cost of the component materials or the manufacturing costs. Sure, the manufacturer will “explain” the price difference in different ways (for instance with more memory or 3G wireless). Do you want some more examples? Here are a few:

Bottled water. How much does that cost? Seriously, how much? People drink bottled water because they want to.

Soda. All you are buying is carbonated water, sugar, and some coloring. Where’s the value that you’re paying for? If you’re thirsty, why not just drink from the tap?

Cars. Take the BMW 3 Series range as an example, where the base model (the 318i ES) lists for £22.690 and the top (petrol) model (335i M Sport) lists for £36,900. Does a bigger engine really justify the extra £14,000?

Microsoft Windows. What justifies the price differential between the various versions (Home Premium, Professional, and so on)?

And let me get to perhaps the most interesting issue. Apple is a premium brand—it sells its reputation on producing expensive gear. You will notice that for all the discussion about the pricing of the models relative to each other, one issue that I have not raised is the actual value. Having a range with a base model and a top-end model means no one questions the price of the base model (because it will always look like a bargain when compared to the top model).

Now think how this principle could be applied to your products. Let’s take the example of a group of songs to create an album. Think of the range of price-differentiated products you could create:

As a first step, you could give away a track or two for the people who think all music should be free. This giveaway could also act as a marketing tool.

You could then make individual tracks available for download (and the whole album also available for download, but at less than the price of the sum of the individual tracks).

You could create a cheap CD with a cardboard sleeve and a plain label.

You could create a regular CD with a jewel case.

You could create a collector’s edition CD with a special booklet, and perhaps include a DVD with videos of you performing some of the tracks. The videos could, of course, also be made available on YouTube at a later date.

The downloads would cost nothing to manufacture, because they are digital files. Pressing a CD might cost you $1 per unit for a short run. This price would include a jewel case and a printed booklet. You could produce this at a lower cost by dropping the leaflet and using a cardboard sleeve. Perhaps this would come out at $0.80 per unit. The collector’s edition of the CD might come in a DVD-sized case and could cost $1.50 per unit to produce.

When it comes to selling these products, you might be able to sell individual tracks for 99 cents, a download album for $8, the regular CD for $10, the cheap version for $7, and the collector’s edition for $20. If you could achieve these prices, then the income from the collector’s edition CD would be three times the income from the cardboard-sleeved CD (see Table 5.2). However, the bigger point to note is the range of purchasing options—you have products with a price range going from free to $20. In short, everyone can choose the price they want to pay.

Table 5.2. An Example of Differential CD Pricing

Manufacturing Cost | Retail Price | Profit ($) | Profit (as a Percentage of Manufacturing Cost) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Free Songs Given Away | $0 | $0 | $0 | 0% |

Individual Tracks for Download | $0 | $0.99 | $0.70 | infinite % |

Album for Download | $0 | $8 | $5.60 | infinite % |

CD with a Cardboard Sleeve | $0.80 | $7.00 | $6.20 | 775% |

Regular CD | $1.00 | $10.00 | $9.00 | 900% |

Collector’s Edition CD | $1.50 | $20.00 | $18.50 | 1,235% |

Before you get too carried away looking at the big numbers, remember that I will talk more about profit margins in the next section. However, you will see that you have options to create different products so that you are selling essentially the same product (the album) for four different prices, depending on what people want to pay (and you’re also splitting off individual tracks too, for those who won’t buy a whole album).

One issue that concerns people when they start looking at differential pricing is cannibalization—in other words, does making something available at a lower price mean that someone won’t buy the more expensive item? To an extent, this is a reasonable concern; however, in practice, cannibalization is less frequent than you might expect, because people pay what they want to pay.

If you are concerned about cannibalization, then ensure that there is always a reason for the more expensive items to be bought. So, in the example above, include some additional songs on the regular CD and the collector’s edition CD.

Albums aren’t the only products for which you can apply differential pricing. For instance, you could charge more for a long-sleeved T-shirt than you would for a short-sleeved T-shirt. Perhaps you could charge $5 more, or perhaps $10, since you are likely to find that your T-shirt supplier will charge you more for the raw materials. There is no real logic for this—if suppliers felt the need to charge more for materials, then they would charge more depending on whether you buy small, medium, large, or extra-large T-shirts—however, you will pay more, so they will charge you more.

Are you starting to see how it all works now? Okay, now go away and think about how you can create a range of products that will be valued differently by different fans with different spending power.

In the next chapter (“Economics 101”), I will discuss the economics of a career in the music industry. For the moment, I want to talk about the economics of products.

How many times have you heard that phrase and wanted to scream? Unfortunately, it is true.

There are things you can do as an artist that will generate money (for instance, writing a hit song), and there are things that do not generate money (sleeping, for example).

Every minute that you are alive has a certain cost. You have to buy food, you have to put a roof over your head, you have to put gas in your car if you want to drive anywhere, and so on. Although you may not be spending money at any one particular moment, over the course of time you do have to spend money.

Therefore, your time as an artist is valuable. If you spend an hour on one project and a year on another project, you will have incurred different costs. Hopefully, the longer project will generate more income. If it doesn’t, then I suggest you complete more of the single-hour projects—they are far more lucrative for you.

When I talk about the cost of time, this is the principle that I am discussing.

When you sell a product, you will receive income—in other words, money. This is great; money is really useful for buying stuff like food. However, you can’t spend all the money you receive, because you will have incurred costs in getting your product to your fans; even if your product is digital (such as a download), there will be costs. In really crude terms, the difference between the wholesale selling price for the product (in other words, the price you are paid for it) and the cost of producing the product is the profit.

The profit is money that you can spend (or money that you can invest to develop more products). If the cost of producing the product exceeds the price you get for selling a product, then you have incurred a loss (which is a bad thing—if you do it too often, you become bankrupt). I make no excuses for spelling out in detail many of the costs you may encounter. If you don’t recognize and factor in these costs, you run the risk of incurring a loss.

There are many costs in developing a product; these fall into the broad categories of development, manufacturing, distribution, marketing, and after-sales service (which I discussed at the start of this chapter). Let’s look at how these may apply to you in a real-life situation. Please bear in mind that many of these areas overlap and may be difficult to separate if you are working on a project, so some of the distinctions I have made may seem slightly artificial.

The development stage of any product is the really creative stage. The most obvious example of product development for a musician is writing songs. New material is the quintessential core of a musician’s new product. For the non-writing musician, finding the right material can be as time-consuming as writing music for other musicians.

Writing new songs can take considerable time. Many artists who sit down to write an album’s worth of material will spend many months honing their material before they are ready to go anywhere near a studio, and even then the songs may need a lot of polishing.

In music, the costs of development are usually the cost of the artist’s time (which usually equates to his living expenses for the development period). However, there may be other costs—for instance, if a band is writing an album, they may hire a studio in which to write. They may need roadies to look after their gear, and the studio may provide an engineer. All of these costs need to be factored into the development of the product.

Not all products have a development cost. For instance, if you write an album’s worth of songs and then use those same songs for live shows, there is no new development cost for the second use of the same piece of development. In other words, you don’t have to write the songs again to perform them in a live setting.

As you use your raw material (in this example, your songs) in more ways (album, live shows, DVD, film soundtrack, and so on), your development costs as an absolute figure will not reduce; however, the costs, set against the total income from the development work, will look far more efficient.

I have given only one example of a development cost. There are clearly others. You can also think about research costs under this banner—for instance, if you are researching the market for producing merchandise.

One of the key factors to note about development costs is that they are usually fixed. In other words, the amount does not change based on the quantity of product you sell, and once you have spent the money, it is gone and cannot be recouped. Also, it is rare to be able to change the selling price of the final product if the development costs are greater than expected. Therefore, you need to think about a development budget before you spend the money, not after.

Manufacturing is the process of taking the raw material (often the song) and turning it into a form that can be sold (such as a digital download or a CD). There can be several stages to the process (and there are different cost implications associated with each stage). Take the example of producing a new CD for which the songwriting stage has been completed. There are then two manufacturing stages:

Recording

Pressing

Recording may be part of the writing process, and there may be little cost if the artist self-records. If this is the case, the main costs are likely to be the artist’s time, electricity, and the investment in recording technology. However, for larger projects, it is common for an artist to record in a studio, in which case the costs will include the studio hire, roadies, engineers, a producer, and so on.

Within the recording costs, there is also the expense of mixing, mastering, and getting the music into a format that can be sent to the CD pressing plant (or uploaded to a download store, such as iTunes).

As with product development, once these manufacturing costs have been incurred, the money has gone, so stringent budgeting will help ensure that you at least stand a chance of making a profit.

There are many costs involved in arranging for a CD to be pressed, beyond those associated with the purely mechanical process of stamping out a number of CDs. These additional costs include everything from preparing glass masters from which the stamp (that is used to stamp the CD) is prepared, to preparing the casing and the artwork.

The costs will vary depending on a range of factors; however, the costs of pressing are generally very controllable. Assuming you are going the glass-master route, there are some fixed setup costs, but after that most of the costs are dependent on the numbers of CDs pressed. The more CDs that are pressed, the higher your costs will be (because you will be buying a greater number). However, with greater numbers you will probably be quoted a cheaper per-unit cost.

The key mechanism for controlling costs (for CD reproduction) is to control the number of CDs that are pressed. By controlling the number of CDs you order, you can also control your cash flow. If you split one large CD run into two smaller batches, then you will probably increase your overall cost. However, by following this course, you can use income generated from selling the first batch to fund the costs for the second batch.

There are, of course, many different products you can offer, and for each product there will be a different and unique manufacturing process. For instance, if the product you will be offering is a live show, then the manufacturing process will revolve around pulling the show together, rehearsing the musicians, and so on.

Marketing is the process by which you make potential purchasers aware of your product. Marketing costs can vary hugely. However, if you were paying attention in the earlier chapters of this book, then you will have built up a database of your fans, and you will know how to contact these people directly (whether through the social networks or by SMS message, email, or some other system).

However, if you feel your database doesn’t include all of your fans (and there is a good chance that it won’t), or you want to expand the size of your fan base, then you may decide on a more elaborate marketing campaign. This may involve advertising and promotion work. In crude terms, advertising will cost you money, while promotion work will take your time (and require you to spend money getting to the location of the promotion).

The amount of marketing you do is likely to have a very direct effect on the success of your product. It should also have an indirect effect of growing your fan base over time.

Provided you have a way to connect with your (growing) fan base to guarantee a certain level of product consumption/sales, you can have a successful product without spending significant amounts on marketing. Beyond that point, your marketing budget can be controlled quite tightly, but once you do start spending on marketing, there is always the temptation to spend “just a little bit more” to get a slightly better result.

Distribution and delivery are about getting the product to the purchaser. This is a simple matter of logistics. However, when you include the human factor and multiply the possibilities for unintended errors by a whole fan base, you will understand why this can be one of the most frustrating parts of the process from a fan’s perspective.

You are likely to get your products to people in different ways. Here are some of the examples of the means of distribution and the costs that will affect your pricing:

If you sell your tracks as digital downloads through iTunes or Amazon, then you will be paid a percentage of the selling price (usually around 70 percent), and if you also use an agent to interface with the vendor, then they may cost/take commission.

If you send CDs and DVDs by mail, then the costs will include the postage, the packaging, and the human costs involved in processing the order and preparing the package to be mailed. You will also incur costs in processing payments. Typically, if you receive money by credit card, then you will receive an amount equal to the price of the product less a credit card processing fee.

With mail order, the customer usually will be charged for postage and packaging, so you may not see this as something that should be included when you are thinking about pricing your product. However, if you don’t get your mail-order pricing right, you will incur a loss, and that loss will need to be funded from somewhere, so I recommend you get the pricing right before you start sending out products. And if you do find that you have gotten the mail-order pricing wrong, then change it at the earliest opportunity.

If your CDs and DVDs are distributed by a fulfillment company, then they will also charge a fee for postage, packaging, processing, and the humans involved in their process. There will also be the cost of getting your CDs/DVDs to the fulfillment service. A whole stack of CDs can be quite heavy, and this can make courier charges quite steep (especially if your fulfillment service is overseas).

If you sell CDs/DVDs at gigs, then you will need to keep a certain level of stock, and the storage space may cost (even if that cost only appears to be the stress of having your stock sitting around at home).

If you sell CDs/DVDs through record stores, then there will be a cost of physically getting the product to the record stores. There will be another hidden cost in that the record store may not pay you for a while (perhaps not for several months). In this situation, while not an explicit cost, there is a price that you will pay for effectively giving the record store a loan.

If your product is a live show, then you will have a large number of expenses associated with putting on the show. These could include the cost of the venue, security staff, getting equipment to the show and getting it set up, as well as transportation and accommodations for everyone involved.

After-sales service may not be something you think about—it’s not as if you’re selling a toaster. However, this is an area you will have to consider even if it is virtually impossible to budget accurately for it. For instance, what happens if a CD you have sold doesn’t play? Or what happens if the mug your on-demand supplier sells is chipped or has a blurred photo?

In many cases, after-sales service will not cost very much money; however, it will take an awful lot of time and may divert you from other activities from which you could be generating income. That being said, replacing one or two CDs may not cost much, but replacing a whole batch of 25,000 could have a significant impact on your profitability if you have to pack and mail out each CD.

Shoddy goods and failure to attend to after-sales service also can do a lot of damage to your reputation.

The purpose of a product is to turn your ideas into something that can make money. The amount of money you can make from your products is determined by a range of factors:

The number of products you sell

The profit you make on each product

There are two factors determining the number of products you can sell:

The number of people who will buy your product

The number of products you have available for sale

It may sound simple, but the more people you can sell to, the higher your income will be (provided you are selling your product at a profit). Although you may have an excellent product, if your market is limited (for example, taking the illustration I used earlier, if you are a classical guitarist), then there will be a ceiling on the number of people who are likely to buy your product. Therefore, to generate more interest, you need more products (so your income per fan rises).

Only you will know your particular situation and your fan base. In light of this knowledge, you will need to decide whether you should spend more time marketing or more time developing a wider product range if you want to positively influence your income stream.

As a side note, do remember that the rule that selling more products leads to more income is true only if you are making a profit. If you have priced your product at a level that creates a loss, then higher sales equates to greater losses.

At the individual product level, one control you have over the income that flows from each product is your profit margin. Irrespective of the cost of production, many products will have a maximum price above which no one (or only a few people) will buy them. For instance, if you are selling a CD, most people might expect to pay in the range of $8 to $15, and you will find only a few who would be prepared to pay more than $20.

Usually you can’t break the ceiling price for a product. However, at other times you can. For instance, if you are playing a gig, then there is probably a ceiling on the maximum price you can charge for tickets. The solution to generating more income in this situation is to sell more tickets, which you can do by using a bigger venue. Obviously, a bigger venue will lead to higher costs, but you should be able to factor these in to ensure that you make greater profits. Also, somewhat ironically, as you move up to bigger venues, your gigs will become more of an event, which will allow you to price the tickets at a higher level.

In broad terms, the profit you will make from any product is the income from sales (which, if you’re selling through a vendor, will be the wholesale cost, not the sticker price), less the costs.

Some of your costs will be fixed; for instance, once you have recorded an album, any studio costs that need to be recouped through the project will be fixed. As we have also seen, other costs can be managed on an ongoing basis—for instance, you can control the cost of CD duplication by limiting the CD run.

The difficulty with costs is that they tend to be big numbers—they’re usually followed by three zeros, denoting amounts in the thousands. By contrast, income tends to come in small amounts—typically, you’re selling single-digit products (if not less, in the case of downloads). This disparity means that it can take a long time to recoup your investment in a project. If you don’t have any money to fund yourself until you are making a profit, you run the risk of bankruptcy.

I will look at some of the ways you can finance your career and your products while you are waiting for your income to start flowing in the next part, as well as consider the wider issue of income and profitability.

At this point I want to illustrate the costs and potential income from a product with the example of a CD project. For this example, I have invented numbers to illustrate my point. You should not assume these numbers are anything close to realistic. More realistic numbers will be discussed in the next chapter. Also, to make this example easier, I have assumed that you are earning all of the income from the CD (in other words, you are selling it directly and are not giving a cut to a retailer). My final main assumption is that you have a source of income to fund your project. To make the illustration more straightforward, I’m ignoring other sources of income that might flow from the recording (for instance, download sales).

For this project, I am assuming we have an established band of four members, who each draw living expenses from band funds of $2,500 per month (in other words, $10,000 per month for the whole band or $30,000 per year per band member—no one is going to buy a Rolls-Royce on that salary).

I will assume that the time spent during the development phase and the recording phase (up to the point that the CD can be released) is 12 months. In other words, the band’s living expenses will have reached $120,000 over that period.

I am assuming that the band has a reasonable following and that there is a manager who will take 20 percent of the net income (which I am defining as the income less the recording costs, but not including the band’s living expenses). I will talk more about managers in Chapter 8, “Building the Team around You.” There may also be office staff (running the fan club, updating the website, and so on) and other miscellaneous unaccounted-for expenses, but let’s not get too detailed yet.

Anyway, for this album project, let us assume that:

The recording studio plus engineer costs $50,000.

The producer costs $35,000.

Mastering costs are $5,000.

The artwork costs $2,000.

There were miscellaneous costs of $8,000 (such as pizzas and beer for everyone when the recording sessions ran over).

In total, the recording costs come to $100,000. This figure has to be recouped before the band can see any income.

For the manufacturing costs, let’s assume that the band gets the CD pressed in batches with the following costs (including shipping from the plant to the band’s distribution center):

The cost for the first 10,000 CDs comes in at $10,000.

The next 15,000 CDs cost $10,000.

Subsequent batches of 25,000 CDs come in at $16,000.

We’ll assume each CD is sold for $10, and I’m also assuming the fan will pay for postage and packing. Let’s assume that there is a credit card charge of 60 cents for each sale, meaning that each CD will bring in $9.40. To make things simple, I am not making any allowance for sales tax (such a VAT or any state or national equivalent).

Before a solitary CD can be sold, the recording costs have come in at $100,000, and the first batch of 10,000 CDs has cost $10,000. Added to this, there is the expense of running the band, which came in at $120,000, so the total spent before any money has been earned is $230,000 (see Table 5.3).

Table 5.3. The Costs of Recording a CD and Getting the First Pressing

Income | Expenditure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

Earnings during recording | $0 | ||

Band expenses during recording | $120,000 | ||

Recording studio plus engineer | $50,000 | ||

Producer’s fee | $35,000 | ||

Mastering costs | $5,000 | ||

Artwork | $2,000 | ||

Miscellaneous expenses | $8,000 | ||

Pressing the first 10,000 CDs | $10,000 | ||

Total expenses to date | –$230,000 |

Assuming the first 10,000 CDs can be sold at $10 (bringing in $9.40 after credit card charges), this will generate $94,000. From this, the manager will take nothing because the recording costs have yet to be recouped. After the sale of 10,000 CDs, the project is running at a loss of $136,000.

With the pressing of the next 15,000 CDs, a further $10,000 will be spent, giving a total loss for the project of $146,000 (see Table 5.4).

Table 5.4. The Costs Incurred after Selling 10,000 CDs and Arranging for a Second Pressing

Income | Expenditure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

Loss on recording (see Table 5.3) | –$230,000 | ||

Cash generated from selling 10,000 CDs (income after credit card charges) | $94,000 | ||

Pressing next 15,000 CDs | $10,000 | ||

Profit generated by project to date | –$146,000 |

When this batch of 15,000 CDs is sold, they will generate an income of $141,000. At this stage, the recording and CD pressing costs will come to $120,000 ($100,000 recording costs, plus $20,000 for pressing 25,000 CDs to date), so the manager will start taking her fee. In this instance, the manager’s fee is 20 percent of the income above recording costs (in other words, $94,000 + $141,000 – $120,000).

After deducting the manager’s fee of $23,000, the project is still running at a loss of $28,000. This means that after 25,000 CDs have been sold, each CD now equates to just over $1.00 lost. To generate more income, more CDs need to be pressed. This time 25,000 will be pressed at a cost of $16,000, leading to a total loss to date of $44,000 (see Table 5.5).

Table 5.5. The Costs after Selling 25,000 CDs and Arranging for a Further 25,000 CDs to Be Pressed

Income | Expenditure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

Losses to date (see Table 5.4) | –$146,000 | ||

Cash generated from selling next 15,000 CDs (income after credit card charges) | $141,000 | ||

Manager’s fee (20% on income over $120,000) | $23,000[*] | ||

Pressing next 25,000 CDs | $16,000 | ||

Profit generated by project to date | –$44,000 | ||

[*] Note that the manager is taking her fee while the project is still running at a loss. | |||

If this next batch of 25,000 CD is all sold (making total sales of 50,000), it will generate $235,000, from which the manager will take $43,800 (in other words, 20 percent of the income from the sales less the production cost).

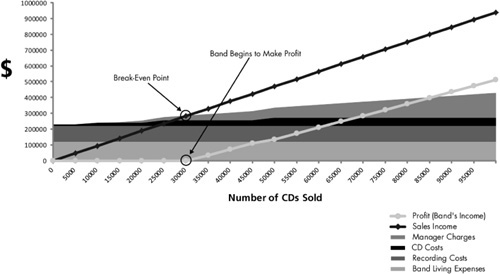

The break-even point is when the expenses have been recouped and therefore any further income is profit (refer to Figure 5.3). At the point that the project sells 29,095 CDs, it will break even, and the band will start to make a profit (in other words, the act will start to generate some income for themselves). However, due to the nature of the product that is being sold here, there is a cost associated with each CD (for instance, the cost of manufacturing and the credit card charge). Accordingly, the break-even point is not as simple as Figure 5.3 may suggest. A more detailed explanation of the break-even point is contained later in this section.

Figure 5.3. An example break-even point. Unfortunately, break-even points are never as simple as this graph may suggest. See Figure 5.4 for a more detailed example.

Having sold 50,000, the CD has now made a profit of $147,200 for the band members—in other words, $36,800 per member (see Table 5.6).

Table 5.6. The Project Finally Moves into Profit

Income | Expenditure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

Losses to date (see Table 5.5) | –$44,000 | ||

Cash generated from selling next 25,000 CDs (income after credit card charges) | $235,000 | ||

Manager’s fee (taking account of the cost of pressing 25,000 CDs) | $43,800 | ||

Profit generated by project to date | $147,200 |

This implies an income for each member of the band of around $66,000 (including the $30,000 living expenses) for just over a year’s work. However, let me add some caveats here.

First, there will be more expenses—for instance, accounting costs, warehousing costs for storing the CDs, and insurance, to give three examples. There could be quite large expenses, such as hotel costs and transportation for the band and their equipment (with roadies) while working at the studio. Second, the band is likely to have to tour extensively to support this album and generate this level of sales. At this level, the income from touring may be quite volatile.

Added to this, it may be two years before the next album is released, which implies the profit would need to be split over two years, giving an income (including the money used to fund living expenses) in the region of $33,000.

Perhaps the most significant caveat is that it is really hard work to sell 50,000 CDs. However, I wouldn’t wish to discourage you from your aim. In fact, why not work even harder and try to sell 100,000? Look at Table 5.7 for an illustration of the income that this sales figure could generate.

Table 5.7. The Project Reaches the Level Where Band Members Can Generate a Healthy Income

Income | Expenditure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

Profits to date (see Table 5.6) | $147,200 | ||

Pressing next 50,000 CDs | $32,000 | ||

Cash generated from selling next 50,000 CDs (income after credit card charges) | $480,000 | ||

Manager’s fee (taking account of cost of pressing 50,000 CDs) | $89,600 | ||

Profit generated by project to date | $505,600 |

As Table 5.7 shows for this example, selling 100,000 CDs could generate a profit for each band member of $126,400, which equates to $63,200 per year if it is split over two years. However, do remember that you may not sell all of your CDs immediately once they have been pressed.

At the start of this example, I put in an allowance of $2,500 per month for band living expenses during recording. If this amount is removed to show the total profit for the project, then the total profit on the project would amount to $625,600. If this figure is split over two years for each band member, it equates to a monthly income of $6,500 (before taxes, savings, or any other deductions).

I will discuss the level of earnings you need to achieve to live on in greater detail in Chapter 7, “Your Pay Packet.” I will also discuss the comparative income you could generate under a typical contract with a record company.

Before we move on, I want to draw to your attention some of the large amounts that have been spent in this project. Some of these charges are explicit (the band has to pay them directly—an example of this would be the studio costs), and others are implicit (and cause a reduction in the band’s income—an example of these would be the credit card charges).

Selling 100,000 CDs at $10 should have generated an income of $1 million. However, the band received only $505,600—in other words, half of the income (and remember that this example assumes the act sells its music directly—the income would have been greatly reduced if sales went through retailers). Let’s have a look at where the rest went.

$120,000 (12 percent of the income) was drawn by the band as living expenses.

$100,000 (10 percent of the income) was spent on recording costs.

$156,400 (15 percent of the income) was charged as the manager’s fee.

$52,000 (5 percent of the income) was spent on CD manufacturing.

$60,000 (6 percent of the income) was spent on credit card fees.

The figure that leaps out here is the charge by the manager, which accounts for 15 percent of the income (although, do remember that the manager’s charge is 20 percent—the discrepancy arises because some expenses have been set against the income before the fee is calculated). However, before you judge the manager too harshly, remember that this is not straight profit for the manager. From this figure, the manager will need to fund her office and many of the costs of running the band. Also remember that in this example, the manager doesn’t take a cent until the recording costs have been recouped, so there is a risk that the manager may not generate any income.

You should also note that in some ways this is a slightly unrealistic number. Conventionally, a manager will take around 20 percent of gross earnings (that is, earnings before any deduction). However, that percentage is normal when a band may be on a royalty of 18 to 23 percent of the price that the CD is sold to a retailer. In other words, if a CD is sold into a shop at $6.00, then the band might receive $1.20 (before the manager’s cut), and the manager would take $0.24 per CD sold.

By contrast, under the business model set out here, the manager could be taking $1.79 per CD sold. This may sound like a large number until you remember that calculated on the same basis, the band could be taking $7.17 per CD after the manager has taken her cut.

If you are going to adopt this business model, you may want to have a discussion with your manager about what expenses should be included or excluded when calculating her fee.

Just to close off this discussion, if the manager was looking after a band with a major recording company, then she could expect perhaps 1 million albums to be sold, generating a fee of $240,000. However, using this business model, we have assumed that 100,000 CDs are sold, which will generate a fee of $179,000. Although $61,000 isn’t an amount to be sneezed at, the fees for the manager in both scenarios are in the same ballpark, suggesting that the fee level may be reasonable.

I will talk more about managers in Chapter 8.

For me, the next charge that leaps out is the cost of the credit card company. You will see that the credit card charges exceed the cost of manufacturing the CDs. This is not an abnormally high fee (although I did round it up). For illustration, a credit card company may charge 2.9 percent of the purchase price plus $0.30 per transaction. If the CD had been priced at $14, then the credit card fee would have been $0.70. Unfortunately, this is one of the charges you have to accept because there really isn’t a viable alternative.

As you read earlier in this book, one of the benefits of running your own career is that you can retain control. To a large extent, you can decide who you work with and how much money you want to spend. This example has illustrated the costs for producing and selling a CD. However, many of the expenses could have been managed in a different way.

For instance, if you had recorded the album in your own studio, you could have cut approximately $100,000 from the budget (although there will be a cost associated with setting up and running your own studio). By contrast, you could have chosen to work with a producer with a world-class reputation and paid $1 million plus for his services.

One of the most important factors in the project I have just illustrated is the break-even point. This is the point at which the project ceases to make a loss and starts to generate a profit.

In simplistic terms, once you have covered the expenses, then the project will move into profit. (Figure 5.3 illustrated this principle.) However, in reality, the break-even point is actually a moving target, because the expenses get larger over time. With the example I have just illustrated, this is particularly so in two areas:

Each time a new consignment of CDs is pressed, there is an expense.

The manager takes a cut of the profit once the cost of producing the recording and pressing the CDs has been met.

You will also have noticed from this example that there was no way that costs would be covered with the first consignment of CDs. Indeed, costs were not covered with the second consignment. It was only after the delivery of the third batch of CDs that the project moved into profit.

There was a logic for ordering insufficient product to cover the costs (in other words, there was a logic why a conscious decision was made to order an amount of product that could never bring the project into profit): controlling cash flow (in other words, not spending more money than was on hand so that as much money could be retained in the business as possible). Keeping a tight rein on spending also has the effect of controlling potential losses. If all of the CDs had been purchased in one lump, it would have cost an additional $42,000 (or perhaps slightly less with a discount for bulk). This would have made a total expenditure of $52,000 on the CDs. Splitting the purchases meant that the band was not left with $52,000 worth of unsold stock (and didn’t have to store and insure the stock).

As a side note, you should also remember that there are other sources of income that could be derived from the music (for instance, online sales, licensing for inclusion on compilation albums, and licensing for use in film and television). All of these additional sources of income could be used to offset any losses.

To return to the subject of the break-even point, this is probably best illustrated by the graph set out in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4. This graph shows how the break-even point is a moving target due to the increasing level of expenses. When sales income exceeds expenses, then the band starts to generate some income.

The recording costs and the band expenses are fixed, as is the cost of the first CD pressing.

The costs rise after 10,000 sales, when the second batch of CDs is ordered. In reality, this second batch of CDs would be ordered before 10,000 sales had been achieved to ensure that the product was always available.

The manager’s fee kicks in at 12,766 CD sales, when the costs of recording (excluding the band expenses) and the costs of the CD pressings have been recouped.

The costs rise again after 25,000 CD sales, when the third batch of CDs is ordered.

There are no profits until the income exceeds the expenses (which, as we have seen, continue to rise). This occurs when the project has sold 29,095 CDs. This is the break-even point. If we had ordered, for instance, 100,000 CDs at the start of the project, then the break-even point would have been much later.

Although the break-even point has been passed, expenses continue to be incurred, which is why the profits increase at a lesser rate than the income.

Lastly, do remember that some expenses are included by way of a reduction to income (specifically credit card charges, which are not explicitly shown in Figure 5.4).

In Figure 5.4, it may look like the band doesn’t fare particularly well. In this business model, the band takes the greatest risk and finances the project. Unlike under a conventional recording contract, the band will also get the greatest reward. Figure 5.5 illustrates this point.

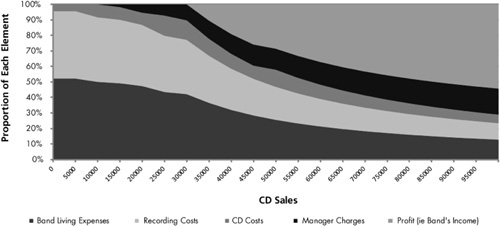

Figure 5.5. This chart shows how the respective proportions of the income are split as sales increase. With greater sales, the fixed costs become less significant, and the band’s profits increase.

This graph shows how significant each financial element is as sales increase. You will see that initially, all of the income is dedicated to meeting the costs. As the income grows, the manager’s charges are also paid. When the project has broken even, then profits are generated and the band can share in the gains.

However, you will see that as sales continue to increase, the profits increase considerably, too. If you were to extrapolate this graph, you would see that the fixed recording costs (including the band expenses) would become comparatively tiny, and the band’s profitability would increase further. Indeed, as the sales increase, the band’s profits tend toward 80 percent of the net income (but will not reach that figure because there is always the expense of pressing further CDs to meet increased demand). The band will never reach 100 percent income because the manager will always take 20 percent.

One point you should note about Figure 5.5 is that the graph is intended to show the main proportions and does not show (for instance) the expense of credit card transactions. Also, until the break-even point, remember that the expenses will exceed income. Until this point, the graph illustrates the relative proportions of the losses.

As a last point, could I remind you that this is a book about building a career in music, not a manual about releasing your own CD? If you are going to release your own CD, then you will need to undertake considerable research (and hopefully, this chapter gave you some pointers about some of the financial aspects that you should be considering).