You might be wondering why it has taken so long for me to get to the chapter about building your team. After all, I have mentioned many of the people who will be in your team in several places throughout the book. Added to that, you have probably already figured that one person who can really help take your career to the next level is a manager.

Let me explain by adding one detail that I have yet to explicitly articulate. So far, I have suggested that you take a businesslike approach to your career in the music industry. However, I am actually going further than that and advocating that you establish your own business. I’m less concerned about whether you decide that the right course for you is to self-release an album or to go with a major record label. Whatever choice you make for how you get your product to your fan base, I am concerned that you treat your business as a business and ensure that it is properly managed.

That doesn’t mean you have to become a businessman or businesswoman and turn up for work at 9 a.m. every morning (in a suit with a freshly laundered shirt and your umbrella under your arm) and then leave at 5 p.m. It does mean that you need the right attitude and you need to ensure that if you don’t look after the business, then someone else (whom you trust completely) is attending to these details.

There are many ways that you can legally structure your business—for instance, as a sole trader, a partnership, a partnership with limited liability, or a limited liability company. I’m not going to talk about these options here because they are irrelevant to the subject of your career. Another reason why I’m not going to talk about the structure of your business is that the options open to you will differ according to your jurisdiction.

If you are serious about your business, then I recommend you get legal and other professional advice, because there are many other implications that flow from the decisions you make about structure. In particular, there are issues of tax and personal liability. I will talk more about getting professional advice later in this chapter.

For the moment, I want to talk about how you structure your business in terms of the roles and responsibilities that people will play in driving your career forward.

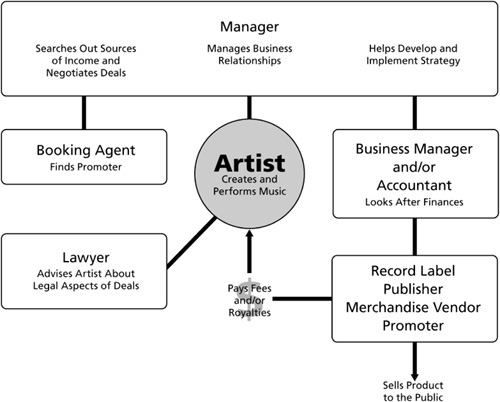

Any business has a range of people who will do different things to help the business. Take a look at any business, and you will probably find most of these people performing the following functions in one way or another (see Figure 8.1):

The shareholders (or partners) own the business and are responsible for appointing the board.

The board sets the strategy for the business.

The management team implements the strategy set by the board, and each member of the board is accountable for his or her own performance.

The workforce undertakes the work that makes the money for the business.

Advisers (such as lawyers or business consultants) offer advice to the board and the management as is needed. This advice could be on a range of issues, from legal points to matters of strategy.

Agents (in the broadest sense—not simply talent/booking agents) are appointed to undertake specific tasks on behalf of the business (for instance, to look after the business’s computers).

Figure 8.1. Who does what in your organization? This is a simple structure for organizing a business. See Figure 8.2 for an explanation as to how this becomes a practical reality.

So how does this apply to you and where do you fit in?

Most importantly, you, the musician, are the workforce. As with any business, it is the workforce who will make the money. The function of the management is to ensure that the product created by the workforce is sold for the best possible price and that the systems for selling the product are as efficient as possible to ensure that profits are maximized.

However, you are also the shareholder of the business—this is your business, after all. You should therefore also be an active member of the board, setting a strategy to propel your career forward.

Before we go too much further in thinking about the team of people, I want to remind you about the range of choices you have.

There are many different things you can do in many different ways. Your focus should be on what you are trying to achieve financially, as well as on the artistic and marketing aspects. For instance, if you are thinking about producing T-shirts, you may have several aims. These could include:

Making money from the sale of T-shirts

Getting as many people as possible wearing your T-shirt to raise your profile

There are many ways you could achieve these aims. These options include:

Ordering some T-shirts printed with your design. (If you like hard work, you can order the stock and printing from different suppliers.) Sell the final product directly to your fan base.

Using an on-demand service and marketing the T-shirts to your fan base. You may also find that the on-demand service generates a number of sales.

Ordering some T-shirts and then supplying them to a range of outlets (primarily clothing stores).

Licensing someone else to produce and sell T-shirts with your logo/branding.

Each of the different options will produce different results in terms of financial return to you and the size of the population that is reached with the product. Some options will realistically only reach your fan base; others are likely to reach lots of people who are not in your fan base.

The options also have differing financial risks from your perspective. As you increase the amount of stock you are holding without having firm orders, you will be increasing your financial risks and increasing the likely costs from storage and other associated expenses.

So, if you are looking for the lowest financial risk and the widest geographical coverage, you may want to consider licensing, although that option may not be the most immediately appealing. However, do remember that just because you have chosen one option, that doesn’t close off the other options—for instance, you could license your product and sell a product directly. (You may even be able to sell your licensee’s stock and generate more income than would be generated from the license fee alone.)

The key issue in this example is that the goal (for instance, to get as many people as possible wearing your T-shirt) is different from the method by which the goal is achieved (for instance, licensing). And remember, to have a valid career, you don’t have to do everything yourself.

Any business will need to expand or contract depending on various factors. For instance, if you run a toy shop, then you may need more staff during the Christmas season. By contrast, if you run a seaside hotel, you probably need a lot less staff during the winter period. (Clearly, the staff who aren’t wanted in the hotel should go and work at the toy shop.)

As a musician with your own business, you don’t necessarily need to have staff (that is, people who you directly employ and for whom you need to deduct tax and social costs from their wages). However, you will probably want a permanent relationship with certain people. For instance, you will want a permanent relationship with your manager—a manager’s job should not be seasonal.

Then there are people whose services you will want only on a temporary basis. For instance, if you are going on tour, then you may need to hire a sound engineer for that tour. At the end of the tour, the sound engineer would then effectively cease to be an employee. When you next tour, you might hire the same sound engineer again, but the contract would still last only for the length of the tour.

As well as hiring people directly, you may outsource some of your tasks. In this instance, you pay someone else to do something for you. The benefit to you is that you don’t have to find someone to undertake the task and, provided you find a suitable service provider, you will be looked after by people whose business is dedicated to performing that task, so you may be able to expect a higher service than if you undertook the task yourself. An example of this arrangement could be if you use a third party to mail out your CDs.

As you will understand, one of the key challenges to running a business is ensuring you bring in the right people for the business needs, and that appropriate service providers are appointed. This coordination is one of the key tasks that a manager will perform. If you don’t have a manager (or someone fulfilling that function), then much of your day will be spent organizing other people.

I now want to look at who the team could be. I then want to think about some of the details of what you could expect from your team members and what they can expect from you (in other words, what you are likely to have to pay them).

One point you should note is that you don’t necessarily need a separate person to fulfill each of these functions—you just need to make certain that someone has responsibility for ensuring that all of the necessary tasks are undertaken.

It is crucial to the success of your business that everyone knows what they are meant to be doing and understands what constitutes success.

If you hire a manager, then there is no point in you trying to undertake the functions the manager should be performing. Although you shouldn’t try to do his job, you should ensure that the manager performs as expected. If performance is not up to standard, then you should end the relationship. Think about a business: If an executive isn’t performing, he gets fired. Why should a manager be any different?

So who should be doing what? Take a look at Figure 8.2 for an example of how the parties work together.

In legal terms, the shareholders (in the broadest sense) are the people who hold the copyrights underlying the products being marketed. So for instance, if you are a band and you all own the copyright to a sound recording (that is marketed as a CD or a download or may be licensed for use as a cell-phone ring tone), then you would be a shareholder.

The board is there to represent the interests of the shareholders and to set the strategy for the business. You probably don’t need the formality of many corporate board meetings; however, it is important that there is a forum for strategy to be discussed and agreed upon.

The board meeting should be open to more than just shareholders. For instance, your manager should have a lot to say about your strategy. (If she doesn’t, why did you hire her?) You should ensure that she is present whenever strategy is being discussed—first for her input, and second because this is the person whose role it is to ensure that the strategy is implemented successfully.

The management team will implement the strategy set by the board and will be accountable for their performance to the board. There are two key players that you need:

A chief executive. This person is in charge of running your business on a day-to-day basis while you are getting on with making music. This role usually is filled by your manager (sometimes called a personal manager).

A chief financial officer. This is the person who looks after the commercial aspects of your business and is often called a business manager. This person will ensure that you get paid and that it’s the right amount. Many artists do not have a separate business manager—they leave the function to their personal manager.

I will talk more about managers later in this chapter.

The workforce undertakes the work that makes the money for the business. As a musician, you are the workforce. The creation of music is a pure blue-collar occupation. Each day you will be working at the factory; whether your task is writing songs or playing a gig, your role is to manufacture the product that is then sold.

You will need several key advisers to assist you in your career.

Perhaps the first adviser you will need is a lawyer. I’m sure you have heard countless tales of young, naïve bands who got ripped off. This tends to happen for two reasons: First, they have little negotiating power, and second, they haven’t taken appropriate advice.

Half of this problem is dealt with by finding a lawyer. The other half of the problem is addressed by ensuring that you have as much negotiating power as possible. If you are running your career as a business and have adopted many of the principles set out in this book, then you will have much more negotiating clout than the average musician.

The other advisers you are likely to need early in your career will include:

An accountant to advise you on finance and tax matters

A banker to help provide funds to run your business

I’ve outlined the various elements of the team. When building your team, you must think about several things.

You need to make sure all of the people in your team work together. You need to ensure that everyone gets along—you don’t want two advisers working for you who are suing each other. You also need to ensure that everyone understands the extent of their role—you don’t want to pay for two people to perform the same task, and equally you don’t want any gaps in responsibilities so that two people can say, “It wasn’t my fault,” when something goes wrong.

You need to make sure you get the right people. Finding the people is hard enough—making sure you’ve got the right people when you’ve found them is even harder. When you’re looking for people, ask around and get any recommendations. If possible, the first people you should talk to are the people who have been recommended more than once. Don’t just look in a directory and hope to pick the right person because you like his name.

When you’ve got a shortlist, then get references on those people. Talk to their existing clients (and, if possible, former clients) to get a well-rounded picture of these people’s business sense.

When you are looking to build a team around you, you may not always be hiring a single person. For instance, if you are taking on a manager, then the manager may have associates. Equally, if you hire a lawyer, then you are probably actually hiring a firm of lawyers. This is a good thing. You want to know that there are other people around to support the person who is working for you.

However, you should be cautious. Many firms will put up a salesperson to bring in new business, and then once your account has been won, they let someone far more junior run the account. Again, this may not be a bad thing—the junior person may be very keen, very talented, and able to dedicate all of her waking hours to your business, plus she will have the resources of the bigger firm and more experienced colleagues to call upon.

However, it may be a bad thing: The junior may be an inept fool.

Whenever you are looking to appoint a new team member, ask who will be working for you. Get to meet that person and make sure she is the sort of person you want to work with. If she isn’t, but you still like the organization, then ask to meet someone else who may fit better with you.

What happens if someone else gets something wrong?

For instance, what happens if your accountant makes an error in calculating your tax figures, so you submit an incorrect tax return? Nothing, you may think, until your tax authority fines you and audits your books. This is a comparatively minor problem—there could be much bigger problems.

One way to protect yourself against any financial cost is to ensure that your advisers have errors and omissions insurance (often called E&O insurance, for obvious reasons). This is insurance to protect their business in case they make mistakes. This is good for you because first, they will have funds to be able to compensate you for their mistakes, and second, their business will not collapse if you raise an errors and omissions claim.

It might seem odd to want to ensure that their business does not go down the tubes. If you find any errors, you may want to take your business elsewhere; however, you probably want to ensure that you can extract yourself in a businesslike manner, rather than losing everything because their business has gone into liquidation.

You can expect professional advisers (such as your accountant and your lawyer) to carry errors and omissions insurance. However, you should confirm this. Some of the other parties you deal with may have some form of insurance, but it is unlikely to be as rigorous as that carried by your advisers.

I want to look at the shareholders. As I indicated earlier, I am using the term “shareholder” in its broadest sense to mean anyone who owns the copyright that underlies a product that is created and anyone who may earn royalties through having sold/ licensed his or her copyright. I am not intending this term to mean only those people who own part of the company if your business is incorporated.

The people who are most likely to be shareholders are:

The songwriter(s).

The artist(s)/band members who each own part of the copyright of a sound recording (or visual performance). Clearly, if you have signed with a major record company, you are unlikely to own your sound recordings; however, you will have an interest in the royalties generated from these recordings.

You may have other shareholders—for instance, the person who designed your artwork. To run your business efficiently, you may want to buy out other copyrights (such as the artwork).

The nature of music is such that you will almost never create a product on your own without any involvement from another person. You may write a composition with someone else, or you may perform with other musicians who have equal rights to you. Whenever you are collaborating, it is important that all of the shareholders work together. For instance, if you co-write a song, and your writing partner then seeks to block its release, not only is this frustrating, but it will stop both of you from earning money.

For this reason, it is important that all shareholders have a common understanding of how their assets are going to be exploited (for the benefit of all shareholders). The most straightforward way to establish and document this understanding is through a written agreement between the shareholders. This could take the form of a band agreement or similar document.

Perhaps the hardest challenge you will face with your co-shareholders is recognizing that you can’t fire these people. These will be people with whom you will always have some link (like two divorced parents), so think hard before you go into business with someone else.

In the conventional way of thinking, you want to find an experienced manager, because these people know the key executives at several record labels and will have credibility with those people. The supposed benefit for you is that the manager can walk into the record label with your demo, and you stand a really good chance of being signed. There’s no need to worry that you’re a bit of a rough diamond; your manager will be able to help the record company see what they are signing.

There is a lot of truth in this view—or rather, there was a lot of truth.

As you might expect, in a changing world, managers are changing, too. Many are getting more entrepreneurial, rather than being pugnacious bruisers. Recognizing major record companies are signing less talent and that due to the increasing number of small labels, they can’t have a relationship with everyone, managers are now putting a greater emphasis on artist development.

Instead of approaching record companies with a diamond in the rough, managers are approaching record companies with a polished product (an act with an image, a professionally recorded and produced album, a video, and so on). By taking the development uncertainty and presenting a record company with a product that is ready to be launched, managers are helping recording companies to significantly reduce their risks.

Another reason why the relationship between managers and record companies is now much less significant is that the income artists generate from record companies (as a percentage of total earnings) is now less significant (although you do still need the central product—the music—from which to generate the spinoffs). As we have already seen, there are many more sources of income from which a manager can negotiate deals. This also means that there is much more a manager needs to understand (and, of course, far more for a manager to get wrong).

So that explains something of what managers can do for themselves. What could a manager do to help you?

There are several main areas where a manager can help you. It is easy to suggest that any one of these areas may be more important than the other; however, in practice, when you are looking for a manager, you want someone who can bring all of these strands together (whether on her own or through bringing together a team of people).

You may not believe it, but you do need a strategy. You need to understand:

Strategy in the broadest sense should be discussed and agreed upon at board meetings, and your manager should be there giving his view about the strategies you should be following. However, strategy then needs to be implemented on a day-to-day basis and refined for a particular situation. Your manager should have a firm grasp of this aspect of your business.

You are running a business. Someone should make sure everything that is meant to be happening is in fact happening.

This means you need someone who understands how business works. That person will need to understand how your income from each and every one of your income sources is calculated and when payment can be expected. He will also need to take action if the money is not forthcoming. Once you have been in business for a while, you may have hundreds, if not thousands, of sources, so your manager must have robust systems (computer databases, paper filing, and so on), or else you will lose money.

You may well use a business manager (and the role of the business manager is discussed in a moment). If you are using a business manager, then your manager should ensure that the business manager is on top of her job.

You need someone to go out and find deals and/or create income for you. Your manager should be the person who finds deals, brings them to you, and negotiates the deal. This may be a deal with a record company; it may be a deal with a publisher; it may be a deal with a CD-pressing plant; it may be a deal with a merchandiser. It doesn’t matter who the deal is with. Your concern is that:

The deal is good for you (both financially and for your reputation).

You are being represented in the best light. You don’t want a manager who makes promises and threats that may be embarrassing to you.

There are no side deals that benefit your manager but not you. He may have negotiated a good deal for you; however, this counts for little if he should have negotiated a great deal.

Artists often have a dilemma when they consider a manager—whether to go with a more experienced or a less experienced manager.

The advantage of a more experienced manager is, well, experience. You can expect this person to know the business and to be competent. However, if a manager is competent and experienced, then she will have other clients, and so the question for you is whether this manager will give you the time you need to help you develop your career (if she will even consider signing you).

You may also find that because the experienced manager already has a perfectly adequate source of income, she may take a rather laidback approach to your career. After all, the manager won’t starve if you don’t get a deal.

The advantage of a less experienced manager is that she has everything to prove and everything to lose. You can therefore expect this person to work every hour of every day to further your career. The disadvantage is obvious: A less (or zero) experienced manager has less (or zero) experience.

However, don’t dismiss a less experienced manager. If she has bucket loads of get-up-and-go and really can make things happen, then that person might be just what you need to kick-start your career. If your manager believes in you, then she is likely to be happy to work for a greatly reduced fee while you have minimal earnings. If your manager genuinely has business sense, then she will help you to start earning money. If she doesn’t, then you may wish to end the relationship.

Between the two extremes you will find a range of people. My only suggestion in dealing with these people is to beware of anyone whose business and acts are mediocre. Some people can see the good in others; some can see the bad: The manager of mediocre acts can see mediocrity. They will find the mediocrity in you and convince you that it is what you wanted. If you want a career that is, at best, adequate, knock on these people’s door. If you want more, then run screaming if you ever find these people.

Each deal will be different, but as a general rule of thumb, a manager will charge 20 percent of your gross earnings (that is, 20 percent of what you earn before any expenses). You may find that there is a commonly accepted figure in your jurisdiction. You shouldn’t simply accept any figure, but rather seek to set a figure that is right for you.

Some managers charge less (for instance, 15 percent), and some will try to charge more. If you have huge earning potential, then you may be able to negotiate below the 15 percent figure. However, if your earning potential is that great, you’ve probably got a very successful career already, and you may feel you don’t need to read this book.

Many artists have perished on the rock of not understanding the difference between net and gross. These are two technical terms that you must understand, because the implications are so significant. As a start, gross is usually a big number, and net is a smaller number (hence managers want their fees calculated on gross figures).

Your gross earnings are your earnings before any deductions. Your net earnings are what you are left with after all deductions. (You may even be left with a net loss—even with a gross profit.)

Say you have a tour, and it generates $1 million. In this case, your gross earnings would be $1 million. If your manager takes 20 percent of your gross earnings, then his fee would be $200,000.

Now, say you had costs associated with the tour of $1.1 million. In this case, your net loss would be $100,000. However, it gets worse if your manager is on a gross-earnings deal, because you will have paid him $200,000, giving you a net loss of $300,000 (while your manager still gets paid).

For this reason, many artists do not like their managers getting paid on gross (especially for touring income).

However, the manager’s counterargument to this is that many tour expenses can be constrained. Taking this example further, the $1,100,000 spent on the tour may, to a great extent, be directly attributable to the artist’s insistence that the whole of the band and the crew stay in five-star hotels and drink the most expensive champagne every night. Perhaps without those extravagant expenses, the tour could have made a profit.

Accordingly, if a manager is going to take a percentage of a non-gross figure, he will probably want to constrain certain expenses—for instance, the manager may limit hotel expenses to a certain figure.

One area to pay careful attention is what the manager’s fee is a percentage of. This is something you should ask your lawyer to look at in detail.

Historically, managers’ fees have been in the 15 to 20 percent range because the manager is running his own business. The manager has an office to pay for, staff to pay for, and so on. However, if you are expecting a manager to run your office with your business, then it may not be necessary for your manager to have his own separate overhead. This would imply that you may be able to negotiate a lower fee.

You may also find that a manager doesn’t want a percentage of gross earnings; instead, he wants a share of the profits. This is much riskier, so it is likely that the share of profits (that is, net profits) will be much higher. A manager may particularly want this kind of deal if he is being more entrepreneurial and developing the act himself. If the manager is taking more risk, then he will expect more reward.

One last thing to think about when deciding on your manager’s remuneration is the issue of post-term commission. In other words, how much are you going to continue to pay your manager after his contract has ended? For instance, if the manager negotiates a record deal, then he may expect some payment for this work. However, if the contract ends before the first payment under the deal is made, you may not want to pay (especially if you have a new manager in place who is taking a percentage).

Clearly, this could lead to much unhappiness on all sides, so you may want to think about the point sooner rather than later. Again, this is an area where your lawyer will be able to give you some very useful advice.

The nature of business managers can vary greatly according to the requirements of the act and local custom.

The identity of the business manager and the manner in which the functions are carried out are irrelevant. For an act running its business on a sound footing, it is important that someone undertakes the functions of the business manager. This someone could be the act’s manager, or it could be an accountant. It doesn’t matter who, as long as the functions are undertaken.

The nature of what a business manager does will vary depending on your needs. However, the main functions you can expect a business manager to perform are:

Monitoring money received and money paid. This may sound simple, but remember that you may have hundreds of sources of income that each need to be individually monitored, verified, and accounted for.

Agreeing budgets (in other words, agreeing how much money can be spent), which may include budgets for recording, making videos, or tour support.

In some jurisdictions (such as the U.S.), it is quite common for a business manager to also act as a financial adviser and advise about investments. In other jurisdictions, this practice is uncommon. (For instance, in the UK, financial advisers need to be regulated, so it is rare for business managers to perform this function.)

There are many different ways that business managers will be paid. The fee structure usually depends on the nature of the relationship.

Some business managers are paid a salary. You may expect to pay a salary (which may be broadly comparable to what the person could earn if she worked for, say, an accounting firm) if you employ someone directly. One advantage of having a business manager on the payroll is that she may also be able to act in other functions (for instance, she may be able to also work as your tour accountant).

Some business managers expect to be paid an hourly rate (in other words, you pay $X for each hour the business manager spends working on your account). This is the kind of arrangement you may expect if you hire a firm of accountants to perform the functions of a business manager.

Other business managers may charge a percentage of (gross) earnings. A typical indicative percentage may be around 10 percent. The business managers who are most likely to look for this sort of fee arrangement are those whose business is being a business manager. These are often accountants who set up their own business-management businesses (as opposed to their own accountancy practices).

One of the most influential factors determining a business manager’s fee is the manager’s fee. If you are paying your manager 20 percent, then it may not be unreasonable to expect that she will provide (or procure) the services of a business manager. It would certainly be regarded as expensive to pay 30 percent in management fees (20 percent to your manager and 10 percent to your business manager).

There are risks in hiring a business manager, in the same way that there are risks in hiring a manager. One of the biggest risks may be your assumptions. Just because someone holds himself out as a business manager, that does not mean he is an accountant. (It doesn’t even mean that the person is competent.)

It isn’t necessary for your business manager to be an accountant, nor is it mandatory that your business manager be regulated by an accountancy body. However, if you are considering working with someone who is not regulated, then you should consider the level of risk you are taking with your business. See the “Errors and Omissions” section earlier in this chapter.

You have probably heard countless tales of young artists being ripped off. The simplest way to reduce your risk of being treated shabbily is to find a good lawyer.

A good lawyer will do several things for you:

Explain what each legal document actually means. You can probably read a contract and understand what each word means. Your lawyer should be able to take that concept forward and explain what the contract (or other document) means in terms of your income (in particular, how much and when) and your obligations (for instance, you may be entering a deal that will take up the next 15 years of your life).

As well as explaining what each contract means, your lawyer should be able to give you some sense about whether you are entering a good deal or a bad deal. The lawyer will have experience in the area in which the deal is being done (if he doesn’t, then run away) and so will be able to tell you about similar deals he has come across.

A lawyer cannot guarantee you will get a good deal. If there is only one deal on the table, and it is a take-it-or-leave-it deal, then all your lawyer will be able to do is warn you about the risks. In this case, the lawyer cannot make the deal financially better, although he may steer you away from disaster.

As with appointing any professional adviser, you should always look for personal recommendations when appointing a lawyer.

When you do appoint a lawyer, it is particularly important to find one who has experience in the music industry and music-industry practices. Given the long-term nature of deals within the industry, advice from a less than competent lawyer can cause you problems over a very long period. Indeed, poor legal advice may end your career.

Ideally, you should appoint a lawyer you trust and respect and with whom you can develop a long-term, mutually beneficial relationship.

Lawyers’ charges depend on the jurisdiction within which the lawyer is operating and the rules of the body that regulates the lawyer (assuming the lawyer is regulated).

In the UK, lawyers are typically paid on an hourly basis, so you will pay an agreed-upon fee for each hour that a lawyer works on your account. Subject to appropriate disclosures and client agreement, fees can be adjusted for other contingencies (essentially success-based criteria); however, this practice is quite unusual in the UK.

In the U.S., hourly rates are still used, but they may be less common in the entertainment industry. Some lawyers are kept on a retainer so the client pays a monthly fee and the lawyer advises as necessary. Other lawyers charge a percentage of the deal on which they are working. A typical percentage may be around 5 percent. A third option that some lawyers adopt is value billing, which is where a fee is charged according to how much value a lawyer feels she has added to a deal. This is likely to be a percentage of any increase to the financial terms of the deal.

However you structure the remuneration, you should have a clear indication of how her fees will be calculated before you instruct the lawyer to start work for you. Ideally, you will have the fee agreed upon up front. If this is not possible, then you should aim to set a limit on the fee that the lawyer cannot exceed without your agreement.

On the subject of lawyers and fees, I would add a word of caution: Always pay your lawyer. Lawyers know how to sue people—there are many lawyers who spend the whole of their professional lives suing people for their clients. If you don’t pay your lawyer, she will sue you, and this will be an easy and cheap thing for the lawyer to do. And don’t think you can fight lawyers by taking them to court. You are likely to find it very hard to find another lawyer who will help you to take legal action against your lawyer.

The main function of accountants is, as the name suggests, to account for things. In other words, they count and make a record of everything.

Your accountant will be able to tell you how much income you have received and how much you have spent. He will also be able to tell you what you have not received that you should have. Many accountants will also advise you on tax-related matters (including VAT/purchase taxes and National Insurance/social charges) and will help you structure your business in a way that is most efficient from a tax perspective.

As with lawyers, you should look to appoint an accountant who has experience in the music industry. There are several (quite legitimate) practices in the industry that may cause confusion for accountants who are not aware of the practices. For instance, it can take a long time to receive your earnings—possibly even years. Accountants without the necessary experience may have difficulty giving you a true understanding of your financial position.

Most accountants will charge an hourly fee. However, as with lawyers, you will find other accountants whose fees can be calculated in other ways.

We’ve already looked at some of the role of banks in the “Sources of Finance” section in Chapter 6.

In short, there are three things you can expect your bank to do:

Receive money on your behalf (whether in the form of cash, checks, direct credit transfers, or credit cards) and then look after that money for you.

Pay money on your behalf. (Again, this may be by direct credit transfer, check, or some other form of transfer.)

Loan money to you. These loans may take several forms, including an overdraft facility or a loan made directly to you.

One other thing you can expect from a bank is for them to shut you down if you don’t pay back money you borrow.

You can find banks in your local neighborhood that will provide basic banking facilities. When you are first starting, these banks may be ideal for your purposes. However, you are likely to be treated like any other customer and will probably find that any loan applications are decided according to criteria that are applied by a central loans department. The result of this may be that you are seen as a high risk (and face it, music is a high-risk business), so you will be turned down.

Once you reach a certain level of success and income, you will be able to make use of more specialized banking sections. You should look for a bank with a department that specializes in creative industries. Once you get hooked in with these people, you will find you are treated much more like a regular business customer.

There are several ways to get gigs. When you first start off, you will probably arrange your own gigs and take whatever you can get as a fee. This may be a couple of beers and a small amount of cash to cover gas; it may be less. If you have a manager, then she will spend a large part of her time trying to find gigs for you until you become an established act (when hopefully you have something of a following and so gigs are easier to book).

As you start to develop a reputation, you may find that you can use the services of a booking agent who will find gigs for you. The main advantages of a booking agent are:

He will have a range of contacts and so should be able to get you more gigs over a wider geographical area.

He should be able to get better fees (since he takes a percentage).

He will free your and your manager’s time (as well as cut your phone bills).

For this, the booking agent may take a fee in the range of 10 to 15 percent of the gross figure negotiated for the gig (and often the manager’s fee will then be calculated on the gross figure less the agent’s fee). Usually, a booking agent will expect exclusivity from his client. This exclusivity may be limited to a geographic region.

The role of the promoter is more venue-specific than a booking agent. A promoter is the person who arranges the entertainment at the venue for the night when you are playing. She will hire the venue and sell the tickets. In other words, this is the person who is hiring you and the person who will be responsible for making sure all of your riders are met (which can range from requiring that certain equipment be provided or certain food be made available, to insisting that the dressing rooms are painted with green, pink, and purple stripes).

Some promoters will work with just one venue, others with a range, and some work nationally.

The artist and the booking agent are both dependent on the promoter for their income. The promoter will be reliant on ticket sales and other income that can be generated (for instance, from advertising/sponsorship; concession stands, such as hot dog stalls; the bar; and so on).

At lower levels, the artist’s fee will often be a fixed amount. As the artist can negotiate better deals, the fee will usually be a percentage of net receipts (in other words, after the promoter has met as many expenses as she legitimately can). Depending on your clout, your booking agent may be able to negotiate an advance (often called a guaranteed minimum) from the promoter. Naturally, this advance will be recouped before you start to receive any share of the net profit.

When you get into the big league, a split of net profits can be in the 80 to 90 percent range (in the artist’s favor and before the booking agent and the manager take their shares). However, you can really expect these figures only when you start selling out arenas. Before then, these figures are just a nice aspiration.

You don’t need a booking agent or a promoter to put on a gig. However, they can prove useful allies to have on your team because they can provide a large chunk of upfront payment as well as reduce your risks.

If you have your own fan base, then there are other options. The first main option is that you can put on your own gigs. This cuts the cost of the booking agent and the promoter. The downside to this approach is that you are taking the whole risk and assuming responsibility for organizing every detail. (For instance, do you know where to find security people or cleaners for the venue, if these are not provided?)

Another alternative, as noted in Chapter 6, is for you to bring your fan base to the promoter and receive a commission (from the promoter) for all sales you make.

As I illustrated at the start of this chapter, there are many channels you can use to make your merchandising available. Remember, merchandising is much more than just T-shirts—it can cover a range of goods, including clothing (hats, scarves, sweatshirts, hoodies, and anything else you can think of to wear), posters, programs, buttons (badges), stickers, patches, mugs, dolls, and so on.

In essence you have two choices: procure your own merchandise and sell it yourself, or license someone else. If you sell the merchandise yourself, then you need to order and hold this stock (which involves investment). If you license a third party, then your main role is to approve the merchandise and sit back and wait for the royalties.

There are many reasons why you may wish to consider appointing a merchandising firm.

A compelling reason for appointing a merchandising firm is that they may pay you an advance.

By appointing a merchandiser, you take yourself out of the whole process, so you don’t need to order T-shirts, store them, and market them. That being said, if it is in your financial interest or if there is demand from the fan base, you may still want to sell your own T-shirts.

Hopefully, even though you will be paid a royalty and will not be taking the full profit, you should be able to generate more income. There are two reasons why your income may increase. First, a firm dedicated to merchandising should be able to get the product to market for a cheaper price than you can. Second, a professional merchandising firm should be able to sell the product at many more outlets.

As a rough (and not particularly helpful) indicator, a merchandiser may pay you anything in the region of 20 to 80 percent of the retail price (less VAT and other sales taxes and credit card charges).

It should go without saying that you need control over copyrights to license other parties to produce your merchandise. For instance, if don’t own the copyright to your logo, then it is likely that the copyright owner could expect to generate some income from merchandise licensing.

In Chapter 6, I looked at the income you might be able to generate from a record company when you release a CD. Now I want to talk about some of the benefits of working with a record label, beyond the fact that they will pay you. In other words, why would you want a label as part of your team?

As well as having a certain degree of financial clout, a record label is also likely to have certain strengths. These strengths include:

Marketing. The record company will have tried most methods of marketing and is likely to have a very good idea about what will work and what won’t. Also, as a regular buyer of advertising, the record company will be able to negotiate the best price. As an act working on your own, there is no way you would be able to negotiate deals as favorable as those a record company can negotiate. Their marketing expertise is also likely to give a significant input into the act’s strategy.

Funding. As you have seen, a new act needs financing in a number of areas—for instance, to record an album, to tour, and to live. Rather than borrow money from a bank, the record label can pay an advance against future earnings.

Logistics. Record companies are well experienced at the mechanics of getting CDs pressed (for the cheapest price and at a high quality) and getting CDs distributed through any and all retail outlets. If the record company does handle the logistics, then they will involve wholesalers and distributors, both of whom will take a cut (which increases the record company’s expenses and so indirectly reduces your income).

Globalization. Many artists are able to find a level of fame in their own country. However, reaching out to an audience outside of their country can be difficult (although it is getting easier). Many record companies have the infrastructure to help artists in their global ambitions.

Clearly, different record labels are going to have different strengths and differing financial resources. As I’ve said for several other issues, look at what you’re trying to achieve. If your aim is to get your product distributed efficiently, then a label can probably perform that task better than you. If you believe that a large-scale marketing campaign is what you need, then you probably want to find a label. However, if you’re after a marketing campaign, you should perhaps ask yourself why your efforts haven’t been as successful as you would have hoped before you approach a label (because the label is likely to ask itself this question).

The downsides to doing a deal with a record company are that they will take a lot of the money you earn, and they will want you to assign the copyrights of your recordings to them.

There are some other apparent downsides. For instance, you will sign exclusively with a record label. However, I’m not sure this is such a problem in practice. Most record companies understand the commercial value of collaborations (especially when it helps you reach a wider market) and will not stand in the way of this sort of work (as long as it is going to make them some money).

Do also remember that record companies are commercial organizations with staff and shareholders that need to be paid. If you are intending to enter into any arrangement with a record company, then your product must be commercially viable from their perspective. To be commercially viable from the record company’s perspective, an album will need to sell enough copies to provide a large chunk of income for the record company.

If the record company takes the view that your album will not sell sufficient numbers so it can make a profit, then it will not enter into a deal with you.

If you are a songwriter, you can publish your own songs and collect all of the royalties that are due by joining the appropriate collection societies around the world. This is feasible; however, if your record is released in more than a few territories (which could be the case if you have a European hit), then it is a tedious task, and the administration will become very long-winded (not least of all because you will need to speak a lot of different foreign languages to join the foreign collection societies).

If you want to streamline this administration, it makes a lot of sense to appoint an expert to undertake this on your behalf. The experts in administering songwriters’ rights are the publishers, so you could ask a publisher to administer your songs on your behalf.

Under an administration deal, you would retain the copyright for your songs and for a fee (typically in the region of 10 to 15 percent) the publisher would collect your royalties and remit them back to you. You would not normally expect an advance under this sort of deal.

However, if you go for an administration deal, then the publisher will administer only your catalogue. In addition to the administration, you may want other services from your publisher, such as:

An advance

Covers for your songs (in other words, you want your publisher to look for other artists to record your songs)

TV/film use (in other words, you want your publisher to find ways for your songs to be used in TV and films)

If you want the money or these sorts of services, then you will probably have to enter into a sub-publishing deal or an exclusive publishing arrangement. Both of these are likely to involve you in selling (or long-term licensing) your copyrights.

Under a sub-publishing or an exclusive publishing deal, the publisher may take around 20 to 25 percent of your gross income (but might take more or less, depending on the deal you can cut). You should be aware that the systems in the UK and the U.S. for calculating songwriting royalties differ. However, the end percentage that is paid may be reasonably similar at the end of the day.

For further details of what you could expect from a publishing deal, check out the “Songwriting Royalties” section in Chapter 6.