Chapter 5

Getting to The Remit

Values We Insist On

At this point we need a brief recap. We established in Chapter 3 that establishing the Remit was central to a high performing team. The problem with this idea is that The Remit, despite being a short word of only five letters, is not an easy ‘thing’ to determine; that in fact there are three key dimensions of The Remit, and they are in a dynamic tension with each other. Readers of other books in our Mapping Motivation series will realise that this is not an uncommon phenomenon in mapping. For example, motivation itself is the product of three interacting and dynamic sources (see Figure 2.5); and, furthermore, even the nine motivators themselves are in three dynamic clusters – the RAG – which are not discrete, but rather holistic in how they affect each other (see Figure S.1).

Thus, although The Remit pitches this interactivity to a new level of complexity, in essence it is something we are familiar with and should welcome. The Remit is What We Do, but this is not a matter we can consider in isolation, but only with respect to the customer (HOW) and the values that drive us (WHY) (see Figure 3.8). Unsurprisingly, because this is tripartite in nature, then it follows the Law of Three.1 This law is too big an issue to cover now, but one important point to note is that wherever the Law of Three operates, something new comes into existence.2 Two forces cancel each other out, and so no progress is made; but the introduction of the third force produces a new resolution, something different, or put another way, the Law of Three is integral to all change.

Activity 5.1

What is the most practical application of the Law of Three as outlined above to The Remit?

This means – in practical terms – that no establishment of The Remit can be considered final; it will always be changing, not necessarily every five minutes, but certainly every few years, if not sooner, and we will need to review it. Indeed, every top performing will have it on its agenda to discuss at least once every year. And this makes sense, for think about it: all three components of The Remit can or may change over time. Certainly, and first of all, the Customer Focus is likely to produce new demands and needs of the customer, which will almost certainly affect what we do; conversely, what we do – a new product or service offering – may well alter the customer’s perspective or demand on us. Values can also evolve and improve over time,3 although some values may be timeless: for example, a value such as – if we included it – ‘honesty’ might never change; but others can, or new ones may be added or even some removed.

With these points in mind, we recall that we looked at the Customer Focus in Chapter 3 and What We Do in Chapter 4. These are essentially notes and tools on what to look for as one builds a top performing team, and especially, as is our interest, with regard to motivation. Now we need to consider the Values We Insist On, the third element. We provided some useful techniques on this in two of our previous books,4 including the correlation of motivators with potential values, positive and negative aspects of the values, and how beliefs and values lead to our choices. Clearly, we don’t want to just repeat that material, and so we refer interested readers to it; but values and motivation are two aspects of work and our lives that need constant attention, and we need a range of tools and techniques with which to examine what is going on.

One of the most powerful tools that we have developed in Mapping Motivation, and which is an intrinsic component of our Motivational Organisational Map is what we call Measuring the PMV scores.5 This is going to take some unpacking, but we think the effort is worth it, since like the Map itself it provides so much rich information.

What, then, is the PMV score and why is this so important for top performing teams and as a tool for management to develop top performing teams? The first thing to mention almost by way of passing is that the Motivational Map is a self-perception inventory tool; in other words, that in completing a map one is comparing oneself with oneself and not with another individual or against a standard. So, self-assessment or self-rating is something that Maps find highly congenial. In a different way, the PMV score is another kind of self-rating.6

We think, for all its obvious subjectivity, that self-rating tends to be accurate except mainly when two unfortunate situations appertain. Self-rating can be inaccurate and misleading when either the self-rater is (1) in a state of fear7 – for example, they are afraid of what their manager might think of the result. Or (2), the reverse – they suffer from a sort of false modesty and a false belief that no one can be a 10/10 because ‘there is always room for improvement’ syndrome.8 In the former case, the self-rater will tend to over-score themselves: in the Maps we see this when we find, for example, PMA scores of 10 for all nine motivators – what chance is it that anybody could really be 10/10 for all nine motivators, including their lowest? Here is someone wishing to appear ‘motivated’ to their manager and not taking any chances as to what their scoring might be. Of course, the false result betrays itself and provides an opportunity for a deeper look at the intrinsic issue within the team.

The latter situation tends to lead to underscoring: the individual does not give themselves enough credit for that they have done, or even how they feel. This is more difficult to detect immediately as an erroneous result, but from a management perspective in building a team, it is more desirable than the first situation – it is much easier to build someone up when it is apparent that they are performing at a higher level than they think than it is to uncover and deal with deception. In Map terms we tend to find that those operating with a ‘always room for improvement’ mentality are more frequently encountered at the operational level, whereas the ‘afraid of what the manager thinks’ is more at the middle management level – those aspiring to get to senior levels and for whom their bosses’ good opinions are vital.

These two exceptions are not the norm. However, we need to be aware of them when we look at the PMV process so that we do not accept results uncritically. Remember: perfection is the enemy of progress – we are not looking for perfect results, but useful ones on which we can take practical action steps. As they say in NLP (Neuro Linguistic Programming), the map is not the territory, which means that all models are imprecise in some way; what we have with the PMV scores is a model that is highly useful.

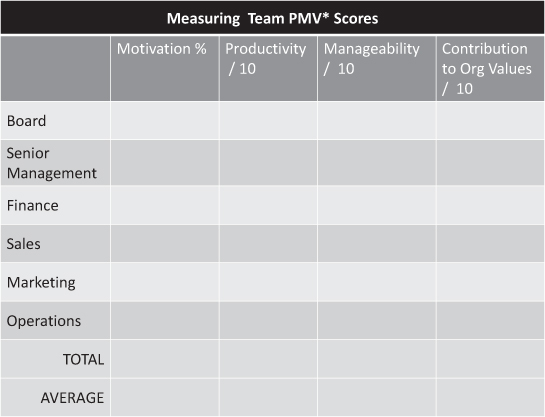

The starting point for considering PMV scores is to take all or some of the teams within an organisation and compare them based along four key elements of their existence. Figure 5.1 shows six teams, starting with the Board of the organisation, considered as a team itself, down to the Operations team. We can fine-tune this analysis by either removing or adding teams as we or management see fit.

PMV* scoring is for each team in each category out of 10, where 10 is outstanding and 1 is very poor.

Activity 5.2

Without further explanation on my part, and assuming that the headings are virtually self-explanatory (although we shall still go on to explain them!), consider any team that you are either in or can observe first hand in your organisation, and score them. It would be particularly insightful and useful if you were able to compare your scores for the team that you are in (you may manage) and to set these alongside a team that you know well in the same organisation, or even perhaps a team you were in before your current post. As a first stab, what do you learn or notice about your team or the other team you have scored?

The first score in the Motivation column is the score from the Team Motivational Map. This will be a percentage score which for the purposes of comparison with the other PMV scores we can turn into a score out of 10, either rounding up or down according to the normal arithmetical rules: so 76% would become 7.6 or 8 out of 10, whereas 75% would be 7.5 or 7.

Before, looking at best methods to generate meaningful data here, let’s consider the column headings and what they mean and might reveal to us.

Most obviously – and as the foundation as it were – we want to know is the team motivated, and at what level? We then have the PMV criteria. These are: How Productive (P) is this Team? How easy to Manage (M) is this Team? And how much does this Team contribute to Organisational values (V)? Note that in this instance we have not included our old favourite P – as in P for performance – partly because it is more directly correlated with motivation, as we have discussed at length in our earlier books, and partly because at the end of the day organisations want the productivity that results from high level performance. Indeed, productivity is the issue of our times nationally9 and internationally.

But just being motivated and productive are not enough, at least for a top performing team; there is more. We think that there are two other vital dimensions to consider: manageability and, our old friend, values! Let’s look at all three dimensions in a little more detail.

First, productivity. In the normal course of events, productivity and motivation should go hand in hand. That is, highly motivated staff should be highly productive. Alternatively, if your staff are poorly motivated and productivity is not high, that should come as no surprise either. We talk of Reward Strategies to motivate employees and teams in order to increase productivity. But what if motivation is high but productivity is low, or productivity is high and motivation is low? These would be counterintuitive results but not entirely unusual. It is possible for staff to be productive but not motivated – at least, for a while. In these situations, one needs to investigate the causes carefully. Some possible reasons for high motivation and low productivity are: lack of skills or knowledge, unanticipated implementation problems, absence of appropriate leadership, flawed strategies, system failures, poor communications and inadequate planning. Some possible reasons for low motivation and high productivity are: insufficient involvement of those affected, fear, economic or cultural climate, focus on things and not people,10 over-competitiveness. Although the latter problem seems less problematic than the former, high productivity in the long run is not sustainable with a demotivated workforce; for one thing, staff leave as soon as that option becomes tenable. The question, then, is how productive are your team? We know how motivated they are through Motivational Maps.

Second, manageability. This is a word we like to use to describe the process of running, or managing or leading a team; the key word here is ‘process’. How easy a team is to manage is also an important issue to consider when dealing with them and considering their value to the organisation. Ever had a customer who spends money with you but is hellishly diffcult to service?

Activity 5.3

Think about a very difficult client or customer you have had in your working experience. What was he or she or the organisation itself like? What problems did this cause for you, your team or your business? How did you resolve this? And finally, knowing what you now know, and if you did a cost-benefit analysis, was having the customer really worth it? What would you do differently, knowing what you now know?

Staff, and teams, can be just like that difficult customer, and sometimes we have to ask whether the value of the team outweighs the problems they may cause. To take two examples at different ends of the motivational spectrum: the Spirit team may be persistently difficult to manage at all; whereas the Friend team may be too dependent on direction and coaxing. The key thing is the fit of the team leader and their style of leadership with the team profile. Thus a team’s motivation needs to be considered alongside their manageability: if they are highly motivated but not easily manageable, then why is that? Do the motivators themselves tell us anything? Conversely, if motivation is low but they are easily manageable what is that saying? Probably, that they are marking time and not optimising performance (so time to compare the productivity too). And again, if they are poorly motivated and not easily manageable, that makes sense – but what to do about it? What, then, does contrasting manageability against productivity reveal?

Figure 5.2 shows us the likely scenarios in each of the four possible quadrants. Regarding the Dysfunctional quadrant, it may result from a clash of competing motivators, or even similar motivators whereby, for example, too many Directors or too many Stars are competing for space. But at its root, it is not the motivators causing the problem: it is the low self-esteem of the team members and/or bad leadership that compounds the problem. At that level the motivators, whilst true, become irrelevant: the wants of the motivators have been replaced by the more basic needs for survival and security. Dealing with such a team almost invariably requires somebody outside the team seeing it objectively for what it is, and then taking decisive action.

As for the Weak Management quadrant, we have here what potentially we can classify as the Country Club style of management. Here, everyone is comfortable, no-one wants to rock the boat, and the expression ‘jobs for life’ springs to mind. There is little change or innovation, for ‘Good ideas and solid concepts have a great deal of difficulty in being understood by those who earn their living by doing it some other way’.11 This can be, though not always, motivationally driven: the motivators most likely to result in comfort and change resistance will be especially the Relationship motivators.12 If we do identify a team as being in this quadrant, then this is an important clue to look for in the motivational profile.

By contrast, the Maverick team, which is highly productive, will certainly have a high motivational root cause, and the most likely scenario for this will be a motivational Growth orientation. And one of the reasons they will be hard to manage is to do with the properties of Growth motivators: namely, their future orientation. In dealing with the future one is always wrestling with uncertainty and ambiguity; and this requires non-standard methodologies for coping with and dealing with ‘things’. Hence, we inevitably have to have maverick-type people who can endure this lack of certainty, this more fluid scenario. Obviously, the Spirit motivator is by its very nature not easily manageable, but it’s not easy either to manage ‘creatives’, for creativity can lead anyone away from the official ‘script’. And Searchers too can be value-driven to make that real difference in a manner that can override the overt and espoused values of the team or organisation.

Finally, the Champions, the dream as it were of all organisations: highly productive teams who are highly manageable. Management gets the productivity they want with the lowest amount of effort and stress involved. Champions can be any combination of motivators, so it is important to emphasize there is no stereotyping here. But all things being equal, the Achievement motivator types are more likely to occupy this space: unencumbered in some respects by loyalty to each other, less troubled by visions of the future, they have a job to do in the present: to get management and levels of control right, to be competitive and to be best, and to be experts – deep experts – at what they do.

Activity 5.4

Study Figure 5.2. Consider any team that you have been a member of or have managed or led. In which quadrant would they be? What quadrant might be the best one for them and the organisation? What steps do you think might be taken in order to shift quadrant? If you’re happy with the quadrant you are in, then reflect on how you stay there. What key factors keep you there?

So far, we have then a series of interesting comparisons: motivation versus productivity, and productivity versus manageability. Each comparison invites us to dig further into the causes, which means to identify what is really going on with a view to improving the situation; and also to increase our self-awareness,13 as individuals and as teams.

Let’s now consider the all-important issue of values and the contribution that a team makes to them. Figure 5.3 shows us a dynamic representation of what we were seeing in Figure 5.1.

If we look at Figure 5.3 we see almost a wheel which affects the ability of a top performing team to operate. The starting point for us is always the immediate, top of the wheel point of motivation. This is because motivation is energy and nothing moves without it. But different teams will have different foci, and one might well be higher purpose and the contribution to organisational values; notice the double arrows we put in where this occurs. This is because realising our values releases a tremendous amount of extra energy; it inspires us as well as motivates us, and this enables a redoubling or more of effort and energy.

Figure 5.3 Motivation, Productivity, Manageability and Values

However, the contribution to organisational values of a team, whilst a core contribution, is not so obvious a factor as productivity or manageability. For a start, it requires all employees in their respective teams to be aware of what the organisational values are, as well as living and working by them; also, for senior executives to make this of first-order importance and to reward it accordingly.

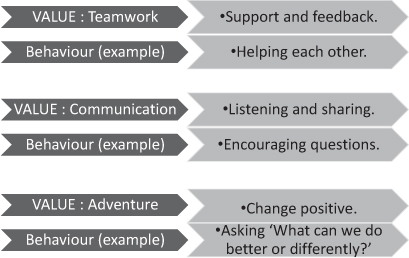

Typically values need to be turned into behaviours. As a familiar example let us consider the core organisational value of honesty – being open and honest in all our dealings and maintaining the highest integrity at all times. As a behaviour this may become: all concerns are aired constructively with solutions offered and each person is as skilled in some way as another and is entitled to express their views without interruption. These two behaviours are ‘honesty’ manifested in behaviours towards employees; but equally, we may – indeed, should – have formulations of honest behaviours towards customers, suppliers, stakeholders and society generally. For how can it be said to be a true value if it is only selectively applied?

Of course, from the organisation values, team values arise, and these too must be treasured, repeated, re-enforced and rewarded. The longevity and ultimate success of the organisation depends probably as much on this key area as it does on the more obvious ‘productivity’.

Further, values are motivational: at one end Defenders love them because they provide stability, and at the other the Searcher wants them because they create deep meaning in the work. Given this fact, we need to consider how motivational profiles may or may not support organisational or even team values. Do they work for them, or against them, or even reside in some neutral space?

Activity 5.5

Suppose the number one organisational value is Customer Focus, whereas a specific team’s number one motivator is Spirit – autonomy. What issues may potentially arise from this situation?

Clearly here, there is the potential for the value and the motivator to be in conflict or to ‘resist’ the value rather than ‘re-inforce’ it. This may be because the team resists or resents the constraints of serving the customer; it may not see either that how the customer is treated is just as important as what they receive; and the customer may also receive an inconsistent service or approach, as the Spirit tends to resist consistency or uniformity. We must insist of course that we are not stereotyping the Spirit motivator team as being incapable of Customer Focus; it’s all going to depend on a number of factors, including other top motivators in the profile, the deployment of roles and individuals specifically, and leadership essentially. But the drift of Spirit is clear: it probably finds Customer Focus perhaps a little boring and inconsequential. On the other hand, if a value like Entrepreneurialism was number one for an organisation, then a Spirit team would ideally align with the value.

To take another, very different motivator: The Star. If a key organisational value were Recognition (in its widest sense), then the Star motivator might be thought to reinforces this value. However, this does not mean, ‘value and motivator aligned, so job done’! Issues can arise even if there is alignment. One such ‘issue’ might be how there can be enough ‘recognition’ to go around to satisfy all? Another might be: is there a blind spot, or Achilles’ Heel, or what we sometimes call in Maps a hygiene factor, in an over-concentration of one motivator?

With these thoughts in mind, then, let’s look how we might tackle this. Figure 5.4 shows three columns in which we can consider how the values sit alongside the motivators.

Figure 5.4 Organisational values and team top three motivators

The top operational values could include any number, but for the purposes of being manageable, we like to consider the top three: what absolutely are the top three values this organisation stands by and will not set aside under any circumstances? Here are the top three from a FTSE 250 company we worked with, three actually from a longer list; the values were expressed in fuller sentences, but to get to the essence we have abbreviated them to a key word and a couple of descriptors (see Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5 Example of three top operational values for an organisation

These are extremely ambitious values, especially as they eschew ‘content’ (as in being profitable or having some sort of commercial or operational orientation) and focus on the process (as in the experience of working in the organisation and how that is going to feel). Needless to say, but we will, that the company has been highly successful over a 10-year period in precisely the content area of profitability and ROE.14 But what are the organisation’s top three motivators?

If we look at Figure 5.6, how is this organisation of several hundred people doing – aside from its financial profitability (which I have already alluded to). The answer immediately is that it is doing very well from a motivational point of view: to score 77% for a whole organisation of its size is a tremendous result in itself; an average type of score for a company of this size might well be below 60%. But now we have to ask, what does this table mean?

Figure 5.6 Top three values, top three motivators and the lowest!

Activity 5.6

The third column asks us to reflect on whether the values and the motivators are aligned. What do you think? Make some notes on any points or issues as you see them.

The key operational value of teamwork is well supported by both the Searcher motivator, seeking to leverage results through team synergies, so that a bigger difference can be made, and by the Defender motivator, which finds greater security and the possibility of better processes through team filters. The Expert motivator is somewhat neutral. Deployed as deep learning that can help others it is positive; but sometimes, particularly when coupled with the Defender motivator, the Expert can resist change and also hoard knowledge and expertise. Given the 77% score, it is highly likely here that the Expert motivator is reinforcing the values.

What about the communication value? Again we have the Searcher motivator prominently seeking to express what it is doing, and driving mission forward; but this time the Expert and Defender combination can be less helpful. Defender-type communications can become monochrome, or mono-channel, and repetitive so that they lose their edge. Combine this with too much information or ‘geeky’ expertise, and the required dynamism of communicating can be lost. It’s as well, perhaps, that the specified behaviours tend towards very empowering types of activity such as ‘encouraging suggestions’.

Almost finally, what about adventure? Well, certainly the Searcher is up for this – making a difference is always an adventure. But here again the Expert can get stuck in their expertise, and the Defender will not like change generally. Here is the area where the consultant or coach can add most value: is the organisation really able to sustain this value? And to answer that we need only look at the one behaviour we have specified from its list: how frequently are team members asking how things can be improved, or completely done differently? Is that part of the life of the team?

Finally, we need to comment on the lowest motivator, since it is a hygiene factor. As we have already established in Chapter 4, the Friend motivator is commonly lowest in many top performing teams, but it is dangerous if motivators stay that way. Here we have the same situation again: a top performing company with top performing teams within it; however, are the teams sustainable? It is true that the company has stayed at the top of its game for 10 years, but talking to HR one soon realises that there has been a lot of unnecessary churn15 as key team members have moved on far too prematurely. What we said in Chapter 4, then, applies here too – see Figure 4.8.

But this little analysis is not the end. There is far more that can be done with this process.

What we now do is look at all or any teams within the organisation and see how they compare with the overall organisation. I have chosen the Senior Management Team itself in this example in Figure 5.7, since starting at the top is always a good idea. And here we see that there is not much difference from the organisational profile, but there is a difference and it is significant.

Figure 5.7 Values, organisational motivators, team motivators

Activity 5.7

What is the significant difference and what might it mean? What else might be worth commenting on?

Clearly, a difference here is the change of the number one motivator: these company directors are actually motivated primarily by the Spirit motivator, and this also involves a polarity reinforcement with the Friend motivator, which is their least important motivator – as it is for the whole organisation. In other words, one might say that the senior team intellectually understands the importance of teams but are not going to be team players themselves! This, of course, will ultimately create cognitive dissonance as they fail to walk the talk of the core value of teamwork – and the requirement for support and feedback. Spirits find all that quite difficult to do, at least consistently.

The combination, too, of two Growth motivators in the top three suggests a much higher risk profile for the leaders, which is far more attuned to the Adventure value they espouse than the whole organisation. What we have, then, is potentially leadership from the top, but which is not wholly accepted or bought into by the teams – who are more cautious, more risk-averse, and so more likely to buy into teamwork and less likely to be adventurous.

Put another way, we can ask the question how far the organisation contributes to its values, and how much individual teams do; furthermore, we can then compare the contributions of each team alongside their motivational profiles and examine how far the motivational profile is responsible, or part responsible, for the situation the organisations and teams find themselves in.

In the case we have just studied the motivational differences were a profound and accurate indicator of what was going on: the senior management team were in fact in sync with contributing to the Adventure value, constantly driving new initiatives, but were far less attuned with the Teamwork value, even though that was considered a higher priority by most of their organisation. However, this took some explaining to clarify, since to persuade the senior people that they weren’t fully contributing to organisational values seemed contradictory to them (see Figure 5.8). Weren’t they the very people who set up the values? Yes, but setting them up and following them are two separate things.

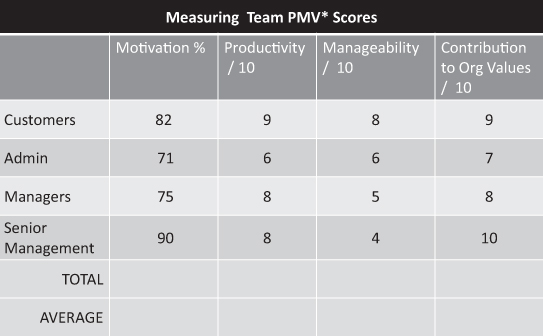

PMV* scoring is for each team in each category out of 10, where 10 is outstanding and 1 is very poor.

Figure 5.8 shows us an actual, though selective, PMV assessment of four teams in the same organisation that we are considering; the motivation scores derive from Motivational Maps but the PMV scores are subjective estimates of the MD.16

Activity 5.8

What are the four most important points that these numbers reveal about the company and the teams, or indeed, the MD?

The first and most obvious point is what we have mentioned in terms of the Senior Management’s self-perception: scoring his own senior team 10/10 for contribution to organisational values is a potential misreading of the situation. And we can see this is the case because the second point would be that, more honestly, the MD realises that his own team’s manageability – that it to say, the team he leads – he scores only 4/10. This leads us to ask just how effective is the senior team when its own leader perceives its manageability at such a low score? Perhaps, to answer that question, we need to drill down further into the team map of this high performing team, which is Figure 5.11.17 We will come to this in a moment.

But before that, however, we see how even at team level beliefs become reality. Admin clearly are viewed by the MD as the least effective team, which their own motivational scores bear witness to; surely, this is a commonplace: most Admin departments – as opposed to the word ‘team’ – are underrated in terms of their contribution to the whole organisation (see Chapter 7 for a striking exception to this), and so frequently remain less motivated than their peers. In this case, however, there is still at 71% a relatively strong motivation. In contrast, and unsurprisingly, though, given how crucial it is to the business, the customer service team is rated most highly. The managers are rated as productive, 8/10, but like their bosses seem not to be manageable, 5/10. Perhaps a case of like attracting like? Perhaps a case of that kind of maverick culture where individual results can be perceived as more important than the collective effort?

Finally, is there an actual correlation between motivational scores and the PMV overall? There would certainly seem to be between the motivation scores and the productivity scores, and also the motivation and contribution to organisational values; the motivation and manageability seem far less correlated, certainly at the managerial and senior managerial levels. And this, perhaps, gives us clues as to where some serious work needs to be done if – as we said – we want to build top performing teams for the long-term. If we set out the scores in a different way, setting the motivation scores alongside the average for the PMV scores and noting the difference, we get the following: see Figure 5.9.

*We have here just taken an average from the team motivational numbers rather than a more exact computing from each individual’s aggregated score, but as the overall score is 77% (or 8) this is accurate enough.

The closer the scoring between the motivation and PMV scores, the more regular the pattern. So, for example, we see the motivation at 8 (80%) and the productivity at 8, which suggests an apt correlation; and we also see the values at 9, a good sign, but the manageability at 6, not so good. This gives us four possible scenarios (see Figure 5.10).

Figure 5.10 is a way of thinking about these data, but not in a prescriptive way. For as we examine the four possibilities, there are some suggestions as to what might be an issue in each of them. To be emphatic again, this is not prescriptive: for example, I have put leadership as a potential issue in the Low Motivation/Low PMV average score quadrant; but, of course, leadership could be issue in any of the other quadrants, including the High Motivation/High PMV quadrant. In this latter case, the leadership might be competent, but not outstanding, and so productivity and motivation could – with focus – improve even further.

So, returning to the question of leadership and our examination of the Senior Team itself and their contribution to the organisational values, it may seem that we have been rather harsh on them, especially considering their undoubted effectiveness and the fact that their organisation has – as its norm – many high performing teams. But we raised this issue because we felt that the scoring in Figure 5.8 didn’t really tally. What does the Senior Team’s own Team Motivational Map look like?

Obviously, with only three people in it, this is a very small and tight team. We can probably be pretty sure that the conclusions we have made so far are accurate as we look at this Map. The two conclusions are: first, that this team is not easy to manage, or manageable, and, second, that it is highly unlikely that it is fully contributing to the organisational values; and certainly not in a 10/10 way, as claimed!

Activity 5.9

Study Figure 5.11 and suggest why both these conclusions are likely to be correct.

Firstly, we note that all three members of the team have Spirit in their top three, which is why it is the dominant motivator; we also note that the Motivation Audit scores for the MD, HR, and FD’s motivators are, respectively, 9, 9 and 10 (out of 10). In other words, they are experiencing massive levels of satisfaction which their job roles are allowing them. Their freedom and autonomy are not being constrained. In a bizarre way, it might be better for ‘teamwork’ if it were, but it is not. Therefore, we can see that they are not being managed by themselves (with an exception outlined in the next paragraph) and do not wish to be so. We can also see, in such a scenario, that they are highly unlikely to be contributing fully to the organisational team values.

Plus, we ought to comment on Kitty at HR. Whereas the MD and FD are very much aligned in their motivators, Kitty is not. The very strong – spike – motivators of Director and Builder, wanting control and competition, also militate against strong reinforcement at senior level of the team values. Interestingly, and as it proved (but positively), what might seem a source of conflict within the team, instead proved to be a necessary strength. The MD did not feel the need to be ‘in charge’ and Kitty’s very strong Director and Builder (note, too, the Spirit is also equally scored at 31 – a real internal conflict in Kitty between her desire for control and freedom) meant that she wanted to provide management within the team, and pick up some of the more day to day issues, and was allowed to do so.

Charles Handy18 talked about the 3i’s of the modern age: information, from which in spotting patterns we generate intelligence; and from interrogating intelligence we can start deriving new ideas. Clearly, Maps are information driven, and from this we seek intelligence as to what is actually going on. Once that is established, we can formulate new ideas to stimulate further the success of the organisation or help them correct what they are doing in order to make improvements. Clearly, in this instance, given the success and seniority of the Senior Team, a simple training programme – implying a leadership deficiency on their part – is not going to cut it. Rather, the focus needs to be around what they all have in common: The Spirit motivator. In other words, a coaching programme that is specifically geared around what Spirits want.

What do they want? More effective time management – freeing up time – and tools and techniques that help them realise their own and the organisation’s vision more comprehensively. And this is what we did. See the Resources section for seven Team Reward Strategies for the Spirit ideas that can potentially be utilised in this scenario. These (and the other motivational-type team Reward Strategies also listed there) can, of course, be used with any team we choose to inspect in this way.

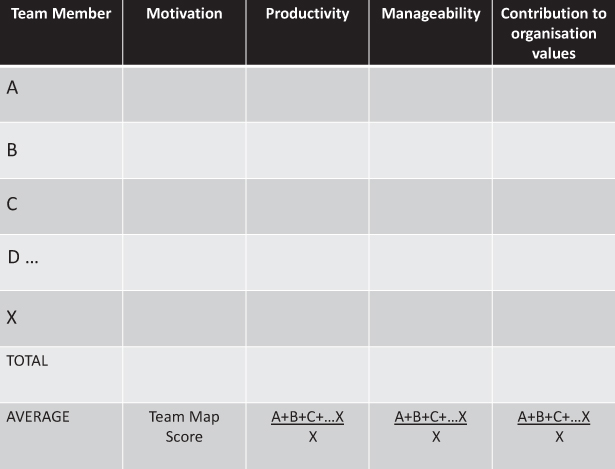

We have covered a lot of new material in this chapter, but we are not yet done, for there is one more point that must be included here. Some of you may already have anticipated this: namely, Figure 5.8 is a highly revealing set of statistics to work from. But as with 360° appraisals, we can improve them by including more views in the analysis as Figure 5.12 shows.

We can go to the team itself and ask every member to rate itself according to the PMV criteria we have discussed, and with their Motivational Map score as the benchmark against which we are comparing progress. The important thing in doing this is to ensure all do it independently and without reference to each other. The same principles apply that we have discussed, but now the collective view adds real power and even deeper insights. Equally, Figure 5.12 can be adapted to be used by senior managers pooling their collective views about the teams under them. Either way, a treasure trove of insightful information and intelligence can be ascertained, and from this new ideas and ways forward be generated.

As we reach the end of this very long chapter – which is itself one of three – we are perhaps quite breathless, as it seems as if there is even more to say about The Remit! But now we must move on and cover another key characteristic of top performing teams: interdependence.

Notes

1 See these three articles on The Law of Three, parts 1, 2, and 3, James Sale, https://bit.ly/2vhlxxS, https://bit.ly/2I9cke1, https://bit.ly/386gHRD (2019).

2 The three forces – whatever their incarnation – may be summed up as follows: The Affirmer (the creator, the life-giver, the instigator); The Denier (the destroyer, the life-taker, the reactor); The Reconciler (the resolver, the bridge, the completer) – see The Law of Three Part 1, ibid. From the point of view of The Remit, What We Do might be considered the Affirmer, but what the customer wants or how they want to be treated might be the Denier. These might cancel each other out, but the introduction of the Reconciler – our values in this case – might provide the bridge between satisfying both competing claims.

3 ‘At this, in a sense, deepest level of our value judgements, there is diversity, luckily, not consensus. The latter would demand regimentation of our intellectual and emotional life’ – Arne Naess, Life’s Philosophy (The University of Georgia Press, 1998).

4 See Mapping Motivation for Coaching, James Sale and Bevis Moynan (Routledge, 2018), Chapter 7, and Mapping Motivation for Engagement, James Sale and Steve Jones (Routledge, 2019), Chapter 6.

5 PMV criteria are how Productive (P) the team is, how easy it is to Manage (M) and how much does the team contribute to organisational Values (V)? That is, Productivity, Manageability and Values.

6 According to Geoff Petty, a leading educational researcher, ‘Carl Rogers places self-assessment at the start and heart of the learning process. And the learning from experience cycle devised by Kolb places heavy emphasis on self-assessment’. https://bit.ly/3cd2jdj.

7 Fear is the great inhibitor of genuine performance; this is why W.E. Deming stated that driving out fear was a prerequisite to high performance and quality: Rafael Aguayo, Dr. Deming: The Man Who Taught the Japanese about Quality (Mercury Business Books, 1991).

8 There is, of course, always room for improvement in the future, but that does not mean that one cannot be a 10/10 in the present. It is a disabling and false modesty to believe that one cannot achieve the highest score, even though tomorrow the bar might be raised even higher. This conditioning is something that must be resisted and turned round: for more on tools to do so, see Mapping Motivation for Coaching, ibid., Chapters 5, 6, and 7.

9 See Stuart Watkins, ‘The Productivity Puzzle: Is Britain Stuck in a Rut?’, MoneyWeek, 29/11/2019.

10 For more on the distinction between people and things, see Mapping Motivation for Leadership, James Sale and Jane Thomas (Routledge, 2019), Chapter 8.

11 Philip Crosby, Let’s Talk Quality (Penguin, 1992).

12 Which is paradoxical, of course, if we consider what we have said in Chapter 4 about the need for more awareness of Relationship motivators if we wish to have longevity. But a paradox is not a contradiction; it’s an ambiguity we have to live with.

13 ‘There is one quality that trumps all, evident in virtually every great entrepreneur, manager, and leader. That quality is self-awareness. The best thing leaders can do to improve their effectiveness is to become more aware of what motivates them and their decision-making’ – Anthony Tjan, Harvard Business Review, cited by Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile, The Road Back to You: An Enneagram Journey to Self-Discovery (IVP Books, 2016).

14 ROE = Return on Equity, a classic measure at how effective an organisation has been in deploying its resources, especially its financial investment.

15 The churn was approximately 40% of staff per year before the advent of the mapping work, and this reduced to 25% after the programme completed its first phase. Operating profit increased by 40% too, but mapping staff was only one factor, in a wider programme, of this general and significant improvement.

16 So, this does not invalidate our earlier point about the main two sources of erroneous self-rating, since the MD in this case is not rating himself but the performance of his own team in very specific categories. In rating others, one can be wrong in one’s assessment for a number of reasons, primarily cognitive or psychological. In this instance, the component which is an actual self-rating would be that for his own Motivational Map; for this he scored 82%, which appeared highly accurate. Naturally, the self-ratings can be extended beyond one person, and this increases accuracy further: Figure 5.12.

17 For more information on this team and this team map, see Mapping Motivation for Leadership, ibid., Chapter 6.

18 Charles Handy, The London Business School, 2015, https://bit.ly/33atcur.