Chapter 3

Getting to The Remit

Customer Focus for top performing teams

We saw in Chapter 1 that there were four primary team characteristics (see Figure 3.1) considered essential if the team were to be high performing. What we now need to do is to consider how to develop those four characteristics in an intelligent and sustainable way; furthermore, to see how motivation plays its part in all this, and how motivation can be deployed more effectively. Keep in mind two things: one, whatever the characteristics are, without motivation the team is dead in the water; and, two, as McKinsey observed1 in their research, ‘rewiring a company … often [takes] 2 to 4 years’. In other words, there are no quick fixes; but that said, we can work towards immediate wins that take us towards the longer term goal we seek.

What, then, is the remit or mission of a team, and how do we strengthen and improve it? Also, what is the link with motivation? The remit is: what are we doing, when, where and for how long? And, for whom? Primarily, though, it appears as – what are we doing? This is not as easy to establish as it sounds. And note too that when we do it and for how long imply that simply having a job and turning up for work is not getting on with the remit; the remit is going to change over time, and so what we do will change with it. Herein is one motivational application: what we do feeds our motivators (or not) but if we have to change what we do, then will we still be motivated? Does the new remit float our boat in the way the previous one did? And aside from how we feel, how would a manager know if the remit was motivational or not?

The changes in the remit come about through various factors: organisational growth, innovations of products, services and systems, marketing developments, legislative changes, and most importantly from adopting a customer-centric approach to activities. Customers inevitably want changes/improvements, and organisations need to respond to that if they are to thrive. Indeed, in some sense the situations are far worse than customers simply wanting changes or improvements: customers even when the service or product is really good may want to swap suppliers merely because they are bored by the provision that they have and think that a new provider might just provide something extra that they feel is missing in the existing provision. Perhaps the only way to guarantee – and can we guarantee? – retention of a customer/client is by achieving the very highest levels of customer service,2 but what are they?

Since we are dealing with top performing teams in this book, it would be good to take a look at a model of customer performance at this point so that we are clear about what we are trying to do. After all, to be ‘top performing’ there must be a relationship to some goal that we are attempting to realise. For many organisations such a goal would be entirely financial: a top performing team would be the team that generates the most revenue, or profit, or which cuts costs most effectively. Such a view would be severely limited, because it would a) make increasing earnings the purpose of an organisation, rather than an outcome resulting from a higher purpose, and b) it would contradict the whole philosophy of Motivational Mapping, since it would imply that everyone is motivated by money or the Builder motivators, which is palpably false. Indeed, we looked at this at some length at the end of Chapter 2.

Activity 3.1

What, then, are the levels of customer service that we need to consider, and which top performing teams need to aim for? How many levels of customer service are there, and how would you characterise them? A clue might be that the answer may not surprise you, given what we have covered about performance so far!

There are, unsurprisingly, four levels of customer service, as there are four levels of performance3 and four levels of motivation; plus, of course, one, where one equals zero. In other words, where there is no customer service at all. So just as we have observed that it is possible to have no performance at all, and this means invariably that one is out of a job or a task or commission because one is doing nothing or something chaotically irrelevant, so too it is possible to encounter a business or organisation where the level of customer service is so lamentably absent that they cannot survive long, even given a unique product that people want. Perhaps the best example of zero customer service is the sort of business that one can frequently (though not always) experience in a local market or bazaar: often products are arranged or scattered in a not particularly useful or helpful way, the attendant simply wants to take money for the product and there is little interaction or warmth, and there is certainly no follow-up or warranty.

But a top performing team is going to be critically aware of the four levels of customer service as an essential outcome of their performance and a key measure of it. The four levels of customer service match the four levels of performance.

A poor level of service is where one gets what you pay for and nothing more. One enters a cafeteria, queues, helps oneself to what is there, and gets to pay at the end. Then one collects one’s own knives and forks to find an available table to sit at. When finished, one puts the empty plates and cups on a tray, and puts the tray where it can be collected for washing-up. Simple, basic, and nobody gets excited by this level of service or returns because of it; we only use it because it might be very cheap or it might be the only convenient place around. Ultimately, businesses like this quickly go out of business.

The good level of service, by way of contrast, is more like the restaurant where you get seated by a waiter or waitress; you may be able to book in advance; the menu is much wider; the quality of food is better; and there is service. This is good but that is all; in one sense it is only fulfilling the plain expectations we have in going to a restaurant at all. The poor service was purely basic; the good service is more functional, but it certainly has no frills or extras.

However, when we get to excellent service things change yet again. Here the customer has been seriously thought about: not just – if we take the restaurant analogy – in the sense that they want to eat something because they are hungry, but in the sense of what they want as part of being human: they want exceptional experiences, they want respect and civility, they want sensory delights beyond merely food and drink, though including that too. So in the excellent restaurant we find a very careful selection of foods and drinks, we find staff who have been well trained and who interact positively with customers, we find a special décor, a particular ambience, perhaps music, and a selection of items (including the cutlery, plates, tablecloth, seating etc.) which have also chosen to enhance the experience. But especially we find that sense of being attended to personally.

Finally, at the level of outstanding service we find ourselves astonished or amazed by the level of product and service. This is where the restaurant goes the extra mile, where the smallest of details can become significant in terms of the whole experience: for example, the waiter remembers one’s name and where one likes to sit, and perhaps other facts of one’s life which they enquire about – ‘How is your son in his new job?’. They probably know your birthday and make a fuss when you go in. It’s where there are complimentary (‘free’!) benefits and discounts; and it’s also where if one’s coat, hat, wallet has been accidentally mislaid, you can be sure that they will contact you and even offer to return it to you, either physically or by post. And it’s where change is endemic: they are constantly thinking of new ways to improve the service, update the menu and provide stimulation and interest, for they know that ‘sameness’ ultimately becomes boring even when it is excellent.

Activity 3.2

Consider who your customers or clients are.4 How would you rate your own personal customer service level: is it non-existent, poor, good, excellent or outstanding? And then consider the team you may be a part of, or a team that works closely nearby within your organisation, or a team that you have observed in action. How would you rate them? Given the service descriptors we have depicted, what reasons would you give for your ranking?

If we look at Figure 3.2 we see that motivation and customer service performance levels both have four levels (plus the zero of no motivation and no service). As we know from earlier work,5 whilst there may not be an immediate correlation between these two dimensions, in the long run they are certainly going to correlate. How could outstanding levels of customer service be performed without there being a corresponding uptick in energy, in motivation? Clearly, one presupposes the other.

A great example – sticking with the ‘restaurant’ services sector – of outstanding service is contained in the Ritz-Carlton Credo. The word ‘Credo’ means ‘I believe’ – we are reaching the point of the remit or the mission that we talked of earlier; the remit that was essential for a top performing team.

The above remit or mission statement in Figure 3.3 is really quite remarkable in several ways. If we take the first sentence, perhaps the most remarkable word is ‘genuine’: can hotel employees genuinely care for their customers? Indeed, imagine that aspiration being transposed to your organisation – can we genuinely care for our customers and clients? What does it take to be genuine?

The second sentence is also pretty amazing and aspirational. Here the key word is ‘pledge’; that’s a very strong word. Not ‘try’ or ‘attempt’ to provide, but pledge to do it, as if it were an oath; like knights of old we are pledged together to achieve the Holy Grail of complete customer satisfaction!7 Imagine your teams ‘pledged’ to achieve the mission – do you think that the pledge alone might have an impact on the performance?

Finally, the third sentence contains the most astonishing clause of all, absolutely astonishing.

Activity 3.3

Which part of that third sentence, which clause, is really and truly astonishing? And since the sentence isn’t that long, why is this clause astonishing? What are its true implications?

The clause that deserves our attention is ‘fulfils even the unexpressed wishes and needs of our guests’. That, if understood in its entirety, is little short of staggering as an aspiration. Why? Because it is something that can only come about as an act of ‘love’! We barely – most of the time – can understand what our friends, children and partners want when they directly express their desires to us; to understand what somebody wants but who hasn’t expressed it overtly requires extremely high levels of intuition, empathy and experience, since it can scarcely come naturally. It is in other words virtually the highest level of service that one can contemplate: staff – the teams at Ritz-Carlton – are being asked to anticipate customer needs in a way that is intimate, personal and effective; this is a million miles away from the bazaar or street market of zero customer service that we mentioned earlier.

And one person cannot do it; it has to be a team effort to function in this way, or else individuals would be overwhelmed with the pressure and simply burn out. That is why, when one drills down in the specifics of what Ritz-Carlton demands of its employees we find ‘basics’ like: ‘Create a positive work environment. Practise team work and lateral service’. Practise teamwork – in order to do what? To achieve the remit. And together – as in T.E.A.M8 – each achieves more by virtue of the support, encouragement modelling of good behaviours that top performing teams inevitably produce.

Before coming specifically to the building of teams, we might want to reflect on the practicalities of these abstractions. When we talk of genuineness, or pledges or unexpressed wishes, this can seem somewhat idealistic and remote from everyday life, especially perhaps in a hotel where working is by its very nature extremely practical. Indeed, Ritz-Carlton suggests as much when it refers to its staff creating what it calls ‘The Ritz-Carlton Mystique’! Mystique – another airy-fairy word. But again we see that having ideals, values and/or a remit is not airy-fairy at all but exceedingly practical.

These three steps in Figure 3.4 are part of a much wider package of practical things to do to realise the remit. But see how simple they are: ‘a warm and sincere greeting’. But as with the word ‘genuine’, it takes real practice to get to ‘sincere’. However, if we don’t start, we will never get there.

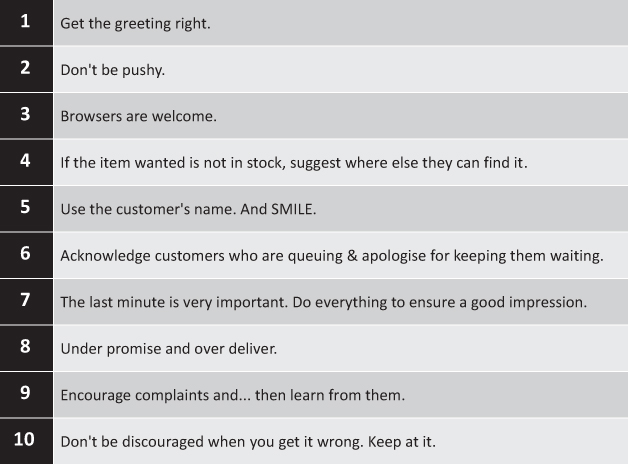

And this is not rocket science really. To take another example: the well-known and highly successful UK high street retailer Richer Sounds has ten things they expect their top performing teams to do. Figure 3.5 provides an abbreviated version of them.

Notice the centrality of the greeting in both Figure 3.4 and 3.5. This makes total sense: we have one chance to make a good first impression, and to be outstanding at customer service is to take it.

Let’s take a look, then, at what we call The Outstanding Index. Here in Figure 3.6 is an abridged form of it. The list of activities that one may need to be ‘outstanding’ at in any given sector may be considerable. In the case, for example, of the Ritz-Carlton they list 20 Basics; other types of organisations may have more or less. But in our Outstanding Index we have reduced the key activities to what we consider the most important five. These five are more or less applicable to any organisation, anywhere, and failure in any of them is likely to be serious in terms of consequences.

In considering Activity 3.4 there should already be enough information in this chapter to be clear about what the various levels are for customer-oriented mission, standards of performance and attitude and motivation. Regarding behaviour, we can consider this as including how individuals, teams and the whole organisation behave, depending on the size of the organisation. Clearly, how individuals behave towards us impacts us most, as does how they appear. But going into any organisation, we immediately also start forming judgements based on appearances too. Now look at Activity 3.4.

Activity 3.4

Complete The Outstanding Index for your organisation or business. Rate yourself and your team as honestly as you can. Then, when you have done this, invite other team members (in the first place) or other colleagues to do the same. Compare your results. Investigate where there are widely differing scores. How does the team you are in address the issues that arise from this analysis? Make a list of the things that need to be done, when and by whom. Remember, the key thing for a top performing team to do is to deliver ‘outstanding’ service.9 Ensure that you are very clear on that.

Activity 3.5

Imagine now that Figure 3.6 has some extra scoring information: Poor is 1 point, Good is 2, Excellent is 3, and Outstanding is 4. Give yourself points for how you rate your Outstanding Index. The maximum score is 20 if you had given yourself 4 points (Outstanding) for each of the five areas of customer care. Convert this to a percentage by multiplying by 5. And again we have four quadrants of performance: 80% and above is outstanding, 60–79% is excellent, 35–59% is good, and below 35% is poor. As with motivational quadrants, below 35% means immediate and remedial Action, 35–59% means one is in the Risk Zone (the Risk here being the business will fail!), 60–79% means you are in the Boost Zone (so that with a little more effort you could achieve Outstanding service) and finally 80% and above you are likely to be providing Outstanding service. The challenge of 80% and above is to sustain it for the long term.

We have, spent some time considering the importance of the customer in determining our remit or mission. So let us now look at the word remit itself and use this as our central concept for working alongside the Motivational Map. The word remit, used as a noun – the remit – basically means the task or area of activity officially assigned to an individual, team or organisation; it also has the connotation of being the matter submitted for consideration.10 Tasks or activities are what we do, and in this way we can think of the remit as being the same as the mission. But in having a remit – if we consider this the matter for ‘consideration’ – there are three distinct areas to focus on; what we do is one of them, the customer and their expectations is another; but finally, if we are going to have a top performing team (or individual or organisation) then the values we insist on are crucial. Hence, The Remit for a top performing team comprises three elements, as shown in Figure 3.7.

In studying this we see three elements of The Remit and we need to realise that they are all interconnected in a profound way, and that motivation is at the heart of all three elements as we shall show. But firstly we must point out that this is what we think a remit really is; not just a task, without any further consideration, but something far more intrinsic, deeper, aligned to human nature and desires, and ultimately highly productive. The point of a top performing team is to be productive, and superior productivity leads to improved profits or organisational results. We cannot cover every aspect of The Remit in a book this size, but what we can cover are the motivational aspects of it, and show how motivation is central.

A cursory moment’s thought – and viewing Figure 3.8 – will show that each of the three elements has a dominant link to one of the three motivational groupings expressed as R–A–G: Relationship–Achievement–Growth. In starting this chapter, we examined the Customer Focus (or Service if you will) as a primary starting point. But what exactly is a customer focus? If we review what we said about the Ritz-Carlton approach we realise that the essence of a customer (or client or patient) approach is relationship driven; for we seek to understand the customer in such a way that if we can truly understand them, then this will lead almost to a form of ‘love’. This applies whether we are dealing with the obvious case of hotel service and its one-to-one interactions, or the less obvious case where we manufacture 100 million bottles of shampoo for world-wide distribution: even in the latter case, the smart organisation is going to think very carefully about the customers (the countries, the languages, the customs and values, the colours even, and so on) if they are going to have the remotest chance of shifting all those bottles! Branding itself is about first forming a relationship in the very mind of the customer. It is inescapable, therefore, that relationship building is at the heart of the customer focus.

This, we remember, is at the base of the Maslow Hierarchy of Needs,11 and accords with the Relationship type motivators in Motivational Maps: the Defender, Friend and Star type motivators relate very strongly, though not exclusively, with Customer Focus for The Remit.

Activity 3.6

How, then, do you think this information might be useful in the construction of a top performing team?

Keep in mind, both that teams are not driven solely by one motivator, but usually the top three have an influence on their preoccupations; secondly, that the R motivators are not exclusively the motivators of Customer Focus. For example, the Expert or the Searcher may well be interested in and concentrated on Customer Focus. But here’s the difference that we really need to keep centrally in mind: for the Expert, Customer Focus or Care is a matter of the mind (that is, Thinking), of expertise itself, of working out exactly how we are going to serve the customer. What we call the Head.12 And for the Searcher the Customer Focus is a matter of making that difference that they strive to do from, as it were, their Body or Gut; it’s the right and direct thing to do and it follows from Knowing what to do, and so they do it. What is different about the Defender and Friend motivators principally is that the desire to serve the customer comes from the Heart, and so from Feeling, and it is that Feeling state that gives it an edge.

The edge derives from the fact that the Heart sees things differently from the Head or the Body; indeed, it might be better to say that it feels things differently from them, and whilst feelings can sometimes mislead and provide distortions to perceptions of reality, in this case we want to know what our customers ‘feel’. We want to be able to empathise with their situation so that our product or service can really solve their problem, issue or need. This is where the Heart motivators are most relevant. Sure, the Expert may provide superior thinking power and analysis of the situation, but this can often be at the expense of what we might call the human dimension or factor; and we are very familiar with this problem in management itself.

If we look at Figure 3.9 and consider what we know about motivational distribution from over 70,000 maps that have been completed, then we understand that asking the Defenders and Friend motivator types13 about how to serve the customer more effectively is exactly what happens whenever an organisation asks its employees and teams to contribute to solving customer issues and improving the service or product. For, although all motivators can be found in all individuals at all levels within an organisation, the reality is that the hierarchy, mirroring Maslow’s, attracts certain types, and for obvious motivational reasons.

The Defender, for example, is risk averse: generally speaking, the higher one goes in an organisation, the riskier one’s position is.14 Conversely, the Creator who wishes to innovate can usually only do so when at a certain and higher point in the organisational structure. Of course, these ideas are not immutable, and advanced and engaged organisations turn these ideas on their head, but as a general principle, we see more Defenders and Friends at the lower reaches of the organisational hierarchy.

And we know that it is precisely at that end of the pyramid that the best ideas for solving and improving the customer experience are to be found, because they are working closest with the customers!15 If we then add into the mix the idea of the Defender and Friend being precisely these kind of people,16 then we have a methodology for improving the customer experience, service or product. It is good that senior management seeks to involve and engage operational staff in the innovation necessary to improve services and products for the customer, but the extra edge and what might be the way forward is in actively seeking out what the operational staff who are specifically Defender- and Friend-motivated (and to a lesser extent Star-motivated) actually ‘think’ or in fact feel.

This is a breakthrough perception (even though it may take a longer time to deliver) for senior management; for if we think about it, we have a double benefit. On the one hand, we have operational staff who work with the delivery of the service or product on a daily basis and, on the other, we have those staff who are most aligned with what the customer wants emotionally. The Defender seeks to get things right, to be efficient, and to drive value for money; the Friend genuinely wants to help the customer, sees the customer as the raison d’être of the teamwork they are practising, and indeed may see them as belonging to, or be an extension of, their team. Thus, although the Defender and Friend motivator-types may not be the most knowledgeable or innovative, they really want to deliver on The Remit. As we know, where there is that kind of attitude, there is usually a corresponding kind of result.

But as I said, this may take time, for we also know that in terms of speed, the Relationship motivators tend to be slow, since they are risk averse. It is clearly a balancing act or judgement call rather akin to the tortoise and the hare fable. Slow and steady can sometimes outperform the fast and impatient! However, it is important to recognise just how useful the Defender and Friend motivator types can be in team work and in creating improved solutions for the customer.

What might this mean in practice? Let’s take a situation in which we have a Motivational Map of a top performing team, but in which the Friend and Defender motivators are low.

Here is a map of a highly successful team working in the high-tech sector (Figure 3.10). The first sign that they are a top performing team is simply their motivational score: 79%, which is almost in the Optimal Zone, and which for eight people is a very strong result. We note that the score probably would be in the Zone but for one member at 59%. As a leader of the team we would want to look closely at that particular map and consider what some of the issues might be.17 However, if we consider the Defender and Friend motivators, what might we find?

Activity 3.7

How might the team strengthen its customer focus by considering the Defender and the Friend motivators? What issues are there to consider here?

The first thing to mention is what the top three motivators suggest to us in terms of customer service. That Searcher is the top motivator, and that no-one in the team has it lowest or has it below 10/40 (the lowest is 17), indicates a team which wants to make a difference for the customer or client; so far, so good. They are also competitive (Builder), which can also be good in terms of driving up standards, although a potential downside might be a commercial orientation that might exploit the customer and perhaps tip the balance from great value to over-pricing. Thirdly, the Spirit motivator is relatively high across all the members, and with Director so low, suggests that the team is more a group of high powered individuals who like to perform – that is specifically, to make a difference to their particular customers – rather than act in a co-ordinated team way. This is reinforced, of course, by the fact that Friend is the lowest motivator of all. People in this team are not coming to work to belong or for social reasons, which means they are likely to be without a strong feeling that they need to support each other.

With these preliminary observations out of the way, then, how can the Friend and Defender motivators help the customer get a better deal – improve the service or product?

Typically, we might ask the team in a session or on some away-day designed around this purpose (to improve the customer experience) just this question: how do we improve our offering? And there will be many good answers to it: the two Creators, especially, will have innovative ideas to put forward, and in the case of Gill, a spike18 of 34/40, there will be a real passion to put forward new ideas. Equally, perhaps, we have three members motivated by expertise, and two of them (Ant and Cathy, 27/40, 28/40) with relatively high scores; so they will wish to contribute to the HOW of what we do next. And, of course, any well-informed member of the team may have good ideas.

But I would suggest here that the leader of the team (Jon) needs to speak privately with Don and ask for Don’s advice. We see that Don is seriously the outsider of the team – sharing none of the top three motivators of the whole team in his own profile – but yet is still highly motivated at 80%, and so almost certainly functioning at a high level. The fact of asking for Don’s advice or help is itself a very ‘Friend’ way of approaching a Friend-motivated type of person. And note that Don has Friend as his number one motivator, alongside Defender as his second. Clearly, Don is a Relationship-driven type of person; he is driven by his Heart, or feeling. Finally, the added benefit of asking him is that he has Expert as his third motivator, so he is likely to have an analytic bent too. Perfect!

Activity 3.8

Imagine that you are Jon, Don’s boss, and you want to ask Don about improving Customer Service, what three questions might you ask him? Be clear about how you would frame them.

Three good questions that might well get the best out of someone like Don might be:

Set-up or permission question:

-

1. Don, I hope you don’t mind, but I wanted to talk to you personally for your help because I know from what I’ve seen of your work, and also from your Motivational Map profile, that you really care about our customers perhaps in a way that others don’t quite get. Are you happy to help me here?

Actual question:

-

2. I’m concerned that we are not doing all we could for our customers, and that we could add a lot more value in our offerings to them. What do you think we could do to be better in this (specific) area?

-

3. That’s some great ideas. How do you think we can sell this to the rest of the team? And how can we implement this to your customers afterwards? Is there a time frame you have in mind?

What we are doing here is using the Motivational Maps within a team framework to identify potential individual strengths to improve a core aspect of The Remit, specifically, the customer experience.

Activity 3.9

As it happens, there is only one team member with Friend in their top three profile. But there are four people with Defender. Geoff has the joint highest score (with Don) at 24/40. However, would we ask Geoff in the same way we have Don? What do you think, and give reasons or a reason for your answer? And if not Geoff, who might be asked?

Actually, we probably would not ask Geoff (unless we had some reason that is not apparent in the Map alone). The central reason we would not ask him is because unlike Don his motivational score is only 59%: he is in the Risk Zone and is clearly not happy with his current situation. Interestingly, he scores his second and third motivators, Star and Builder, as only 6/10 and 5/10 respectively, so he is unhappy with the pay and his personal recognition. It suggests he is not really fitting in; asking him for help might boost his Star motivation – and this is a judgement call that Jon would have to make – but it is probably unlikely. At a certain point a low motivational score means that one spends more time thinking about one’s own situation than one does how customers are experiencing the service, and so the advice is not likely to be insightful.

If we had to choose one extra person, then it would probably be Andy, who has a Defender and Star combination. This means that two of this three top motivators are Relationship driven and so like Don, though not to the same extent, he will have a more feeling-based as well as systematic view of what might work for the customer. And, unlike Geoff, Andy is 84% motivated, suggesting a high performer.

Interestingly, of course, the other team member who has Defender in their top three is Jon himself, the leader, and asking himself is not going to be useful here! But note, how Jon asking Andy is particularly helpful in that Jon’s own top three motivators are dominantly Growth, at the other end of the spectrum from Andy. In short, we are getting motivational diversity here – the good leader is going to be someone who realises that their own motivational perspectives need challenging and, for Jon, Andy (keeping in mind that Don is even more so) could provide that different way of looking at issues.

In this chapter we have covered what we consider The Remit for top performing teams to be and provided some detailed analysis of the Relationship component which relates to a Customer Focus. Let’s also not forget what we said in Chapter 2 about Reward Strategies: given how we have positioned the Friend motivator in this study, why not check out the Team Friend Motivators in the Resources Section to see if anything there might work here?

Our next chapter will look at the second component of The Remit – What We Do – and investigate its motivational elements.

Notes

1 Ewan Duncan, ‘In order to rewire a company to become a customer experience leader for most companies this will be a two-to-three-to-four-year journey’ – The CEO Guide to Customer Experience, March 2016, https://bit.ly/2XBa8Di

2 Abraham Lincoln observed that ‘The only security you can ever have is the ability to do your job uncommonly well’ – and what is true for the individual, applies equally to the team. Cited in Victory! Applying the Proven Principles of Military Strategy to Achieve Greater Success in Your Business & Personal Life, Brian Tracy (TarcherPerigree, Penguin Random House, 2017). Also note, ‘Customer service has become so important today that every successful business is in the service business’ – Leonard Goodstein, Applied Strategic Thinking (McGraw-Hill, 1993).

3 These four levels are actually four plus one, where one equals zero; in other words, no performance or motivation or service at all. It doesn’t count as a level since it is a complete absence or negation. But there are four levels because the Pareto Principle is based on an 80/20 ratio, or 4 to 1, and this also seems to intuitively fit our understanding of performance. For more on the Pareto Principle and Mapping Motivation, see Mapping Motivation, James Sale (Routledge, 2016) and especially Mapping Motivation for Coaching, James Sale and Bevis Moynan (Routledge, 2018), Chapter 3.

4 Actually, if you work for an organisation you will doubtless believe your customer/client is whoever your boss says it is; but the reality for all employees, especially cost centres, is that your real customer is your immediate boss (that is to say, internally directed), since without their support your own career and progress is likely to be severely handicapped. Furthermore, within most organisations some teams are outward facing, that is, directly to and for the customer, whereas others are inwardly directed: administration or HR for example. But whoever the customer is, the top performing team will be driven to supply outstanding levels of service.

6 As with all organisations mission statements are updated over time, and we have used one particular incarnation of their remit. For the latest go to: https://bit.ly/34vJfCg

7 It is worth reflecting for a moment on this mythological image of King Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table, for it is a symbol for a top performing team. King Arthur may be the CEO, but remember the table is round, so that all are considered equal. Also, the knights are valued specifically for their own special skills and talents. True, Lancelot may be the bravest or strongest, but the stories of the others are equally important, and they all shine in their turn. Only treachery – that is, sabotage from within – ultimately defeats them; it is not an external enemy or competitor. If we think of the demise of most organisations which were once successful, we find that internal problems account for most of the collapses which occur.

8 T.E.A.M. is an acronym standing for Together Each Achieves More.

9 According to Gartner, ‘With 89% of businesses soon to be expected to compete mainly on customer experience, organizations that take customer experience seriously will stand out from the noise and win loyal customers’ – https://bit.ly/38b8HPy

10 The Chambers Dictionary, Tenth Edition, 2006.

12 For much more on RAG and the Heart, Head and Body connection, See Mapping Motivation, ibid., Chapter 3. Also, Mapping Motivation for Coaching, ibid., Chapter 4.

13 The Star motivator is also a Relationship motivator, but it has special properties that sometimes run counter to the Friend and Defender motivators. More aspects of the Star motivator are discussed in Chapters 6 and 7.

14 For the reason that the ‘buck stops here’. Though in cartels and country clubs there will be exceptions to this general rule.

15 We have cited this research in the previous chapter, but it is worth repeating here: according to Sydney Yoshida, ‘The Iceberg of Ignorance, Quality Improvement and TQM at Calsonic in Japan and Overseas’ (1989), the top executives are only aware of 4% of the problems, the team managers of 9%, the team leaders of 74% and the staff of 100%! – https://bit.ly/2DNPae5

16 Not forgetting of course that individual’s motivators change over time, and so one is not stereotyped. Indeed, the journey from being an operative to CEO of an organisation may well be accompanied by a radical shift in one’s motivators.

17 Three obvious points for reflection might be: that Geoff only shares one of the top three motivators of the team; he feels underpaid for his contributions, since he scores his Builder only 5/10; and finally, although the spread of his scores is 9 (15–24), these two motivators are outriders, for the majority of his motivators are clustered around the 20 score – in other words, there is a distinct lack of differentiation in his motivators which may lead to indecision and indecisiveness.

18 A ‘spike’ is a score of 30 or above, and indicates a particularly intense desire for this motivator. An inverse spike (scores of 10 or below which signal the motivator is becoming more an aversion than desire) shows, as the name indicates, the reverse situation.