Chapter 4

Getting to The Remit

What We Do

We now pursue our investigation into The Remit. In Chapter 3 we examined the Relationship (the R of RAG) aspect of this and how top performing teams had to keep the customer in the forefront of their thinking if they were to continue as a top performing team. The word ‘thinking’ here, of course, we extended to mean ‘feeling’: in essence there were motivators that are specifically about ‘feeling’ and consulting team members who were driven by these motivators could make a massive difference to the outcomes for the customer as well as for the organisation.

The second strand of The Remit that needs to be consciously addressed by the top performing team is the ‘What We Do’ component. We linked this with what in Motivational Mapping we call the Achievement-type (the A of RAG) motivators that are very expressly connected to what organisations, and certainly businesses, see as their primary goal.

To be very clear about this, and provocative too, many businesses seem1 oblivious to issues such as belonging (Friend), security (Defender), or recognition (Star) at the Relationship (R) end of motivation; and equally can be blasé or indifferent to innovation (Creator), autonomy (Spirit) or even making a difference for their customers (Searcher). But, is any organisation or business unmindful of power or control (Director), money or resources (Builder) or even expertise or skills (Expert)? One would struggle to think of one, except in the sense of some utopian project that very quickly went out of business!

The reality is that the Achievement motivators (Director, Builder, and Expert) define for most people what running an organisation is all about, and even non-profit organisations have to focus on where the finance comes from. Therefore, typically, making things happen in order to get ‘achievement’ in an organisation, we see what is in Figure 4.1.

Things ‘happen’, then, because management controls resources (money) and develops expertise, which leads to service or product creation, and customers pay more money for this and so the cycle continues. Of course, what I have deliberately omitted from this illustration of making things happen, or ‘achievement’, is the people dimension: money2 may not be a person, but management is made up of people, and the expertise also resides in people, even if machines and computers can sometimes provide expertise. Even in this situation somebody has to interpret or convey this information in some way. People are at the heart of organisations, yet sometimes you’d never guess so; it all seems to be brains or in certain cases muscle and sinew (where there is a large physical component to the work – for example, fruit-picking on a farm).

When things are not happening – when achievement is lacking – the typical tendency of organisations is to do more of what they do! They double-down on what they are doing. So management needs more management,3 more money needs to be invested, and more training and/or expertise are needed. Of course, this may be perfectly correct. But there is a big motivational danger.

Activity 4.1

From a motivational point of view, what might be the dangers of an organisation responding to a crisis by imposing more management, or supplying more resources as made available by more money, or by developing greater expertise? Remember that any two or all three might simultaneously be supplied: more money might, for example, be spent on training for managers. Think about your answer purely from the point of view of the nine motivators.

Here we have a fascinating scenario that can easily become counterproductive from an organisational or business perspective. First, if management decides to tighten up – usually under the guise of improving – there is invariably an increase in the scope of the authority of the managers. The danger here is that the Director motivator becomes over-dominant and in particular begins to suppress its opposite motivator, the Spirit. In other words, there is increasing micro-management which is demotivating for the Spirit motivated, and these may include some of the managers themselves. Indeed, we have frequently observed, in the SME business market specifically, many Managing Directors combine the Director and Spirit motivator in their top three.

Similarly, the overuse of money, however it be deployed, can lead to the perception that all problems are solvable through financial means, and that only money counts when dealing with issues. This of course is dangerous motivationally for those who are Searcher motivated. And this is doubly dangerous because in our research the Searcher is by far and away the most common motivator in an individual’s top three.4 A wholly commercial approach to achievement, therefore, is likely to be demotivating for a large number of employees at all levels, and this includes (see Figure 3.9) top management.

Finally, and seemingly innocently, the over-commitment to developing expertise can also create problems. In particular, it can stifle innovation or the Creator motivator. Expert and Creator often go together as a pair in happy harmony: deep knowledge can lead to innovations and new ideas; but equally, expertise that is too process and systems driven can stifle innovation, and there becomes one right way of doing things which no-one ever challenges alternatives. This is particularly true when a strong Expert motivator is combined with a strong Defender motivator. In such situations, a risk-averse caution to new ideas tends to creep in, and knowledge can become fossilised.

In a way these dangers are aspects of what we called in another context hygiene factors.5 The strong focus in one or some limited area, such as Achievement (A), can lead us to overlook the importance of other motivators that may be necessary to drive through success in the longer term. We cannot easily change individuals’ motivators in the short-term, but the more self-aware we are of what the necessary motivators are in a given situation, or goal, the more likely we are to be able to create the right balance and emphasis in terms of the team motivational profile.

To illustrate this in some detail consider Figure 4.2.6

Activity 4.2

Figure 4.2 represents an analysis of over 5000 Motivational Maps carried out on ten sectors over a period of time. The sectors have been selected merely to exhibit variety; the Maps were done in various organisations across the whole organisation, and so employees at all levels were mapped, although the majority in this sample were at the middle and senior management levels. Specifically, here we are looking at the frequency with which a motivator was ranked first, or top, by an individual. So we see, for example, more than 40% of the mappers ranked Searcher as their number one motivator. Indeed, we see across the ten sectors that Searcher was by a considerable margin ranked first. Keeping in mind that the sample size (~5000 Maps) is relatively small and that we are not taking the roles or seniority of the staff who participated into account, what preliminary observations would you make on this table of results? List three points that you think might be important.

Given what we are talking about here – what we do and how this aligns or does not align with our motivators – a number of important issues arise.

First, as we have already discussed, though organisations can be preoccupied with Achievement-type motivators – Director, Builder and Expert – the reality seems to be that few organisations have people in them who actually want to manage (Director) and surprisingly who want to make money (Builder). From the sample we see that only 3.3% of individuals had Director as their number one motivator and it does not appear in the top three of any of the ten sectors. And, although the Builder motivator is doubly more common than Director at 7.7%, it still features only as third in the ranking and in just one of the ten sectors – Financial Services! Well, that makes sense, since you’d think Financial Services might employ people preoccupied with money; but, then again, presumably you’d think the same about cognate sectors such as Accounting and Insurance, but Builder does not feature in their top three. So it appears for all the hype, will-power and cultural norms around being in control – managing – and making money, at some deeper level employees – at all levels – largely want something else.7

Second, the dominance and frequency of the Searcher motivator needs careful consideration and explanation.8 What is particularly significant about this phenomenon, which we have noticed in other samples that we have taken, is that Searcher is at the top of the motivational pyramid (and Maslow’s Hierarchy) and is the motivator pre-eminently concerned with making a difference or ‘WHY’? In other words, it is the motivator of purpose. As Simon Sinek9 expressed it, ‘WHAT companies do are external factors, but WHY they do it is something deeper’. And he goes on to say, ‘In business, like a bad date, many companies work so hard to prove their value without saying WHY they exist in the first place’. So we come to the fundamental position of saying that what we do has to be underpinned by a purpose, or a WHY; and in the absence of that WHY the evidence from Motivational Mapping in mapping tens of thousands of individuals is that the organisation cannot succeed in the long-run if they do not take into account the WHY, since so many of its employees crave the purpose or meaning of what they are trying to do.

Third,10 the ‘hygiene factors’ that we alluded to previously now come to the fore. We note that three motivators in particular Friend (ranked 7th), Director (ranked 8th), and Star (ranked 9th and lowest in all 10 sectors) do not appear in any of the sectors’ top three motivators. What are the implications of this? Well, we have already seen in Chapter 3 how the Friend motivator might be exactly the perspective we need to adopt in understanding the customer. The absence of the Director motivator seems almost equally worrying in that it is the Achievement motivator par excellence, and yet it is not one that is really firing up many managers: they are doing the job or fulfilling the role for other motivational reasons, but this can easily lead to a shortfall in how the job is being done. Finally, the universally low scoring of the Star motivator is deeply concerning as recognition is at the heart of it. That individuals are not on the one hand seeking personal recognition may sound altruistic, but is it actually realistic? Virtually all authorities agree that recognition is essential11 if people are to flourish; it’s a primary relationship motivator – it’s about gaining strength, as it were, from others who acknowledge us.

What this third point leads to is a need for organisations and teams to review three key areas: 1) how communications occur within the organisation/team and with a special focus on the sense of belonging that the Friend motivator drives; 2) how management operates and how managers are selected and developed within organisations and teams, or the Director motivator; and 3) how recognition is attributed and awarded with organisations and teams, and how much focus there is on it. Interestingly, the Friend and Star motivators are both Relationship-driven, and Relationship-driven motivators are bound up with helping the customer. Thus, we return in a way to our preoccupation in Chapter 3 with the customer.

Let’s take the ‘What We Do’ from Figure 3.8, and based on what we have said above expand it further in Figure 4.3.

We see from this the centrality of the Why or purpose around the customer. Also, we are driven to ask how we do what do: what activities and delivery methods do we use? Here we are essentially also asking, how do we perform when we do this? And our performance crucially leads us back to considering the skills, knowledge and motivations of our staff. Finally, we see the What – our products and services – also needing to have a customer focus too; we have to ask, what do we supply? And, who is this for? And, of course, do or will they want it? As we ask that question, we are immediately into the realm of strategy12 for the organisation: how do we differentiate13 our offering, what is our unique selling proposition, or why should the customer buy from us? But note the strange paradox of considering what we do, and what we do derives from two points more primary: why we do it and how we do it!

What we have, then, from this is something like Figure 4.4.

If we study this, we realise that determining what we do is not just a simple question of saying I intend to sell mobile phones or houses or panini or beer – to illustrate services as well as products – or surveying or nursing or coaching or teaching. On the contrary, what we do is framed in the first instance by Why we are doing it. This will almost certainly be a value that we attach great importance to. In motivational terms the ultimate ‘why’ motivator – the key motivator – is the Searcher, for why we are doing anything is ultimately to make a difference. To phrase this slightly differently: we can make a difference, but sadly this difference can be a negative one; what we are seeking, if we are psychologically healthy, is to improve the life of the customer in some fundamental way. This is true even at the level of a supermarket selling bread14: whilst it is true that the customer may not see buying the bread so much as an improvement but more as a necessity, the point remains relevant.

Activity 4.3

To labour the issue, perhaps, but how would you make the case for buying bread in a supermarket as being an improvement in the life of the customer?

In the first instance, the customer is given a choice of breads, and so is able to choose their ‘preferred’ bread, which perceptually may be an issue of quality or cost, but either way benefits the customer’s life. Second, although bread may be regarded as a need, its absence leads to a form of hygiene factor: we take it for granted till we don’t have it, and then we realise how important it is to our lives.15 Third, properly understood, the bread is beneficial to our lives in the sense of its potential taste and freshness, as well as the nutrients it supplies us with. For these reasons alone, then, we can see that the selling of anything or everything is about adding some perceived improvement to the life, experience or situation of the customer.16 Hence why the Searcher motivator is the key motivator here, for it could be said to underpin all transactions; and at their best, the purchases may be transformational for the customer and the supplier.

However, all the motivators offer clues as to the WHY we do what we do. Figure 4.5 sets out a table with some information regarding the contributions each motivator is likely to make; and also supplying some sector examples of where this particular WHY might be extremely prominent or operative.

Before discussing Figure 4.5 a number of points need to be clarified. First, motivators are internal drives – energies if you will – but in seeking, say, freedom or autonomy for ourselves (Spirit) we tend to project them outwards and assume or even want them for others. So with all the motivators: our own energies drive us to build a world based around them, and as we have said in previous books these become values for us.17

Second, we must note that motivators can and do interact; but for the ease of simplicity, and because in Figure 4.2 we presented a ranking based on the top motivator only, it is best to consider them in isolation. That said, an organisation may have a complex series of WHYs, though as with values – which are always hierarchical – there will always be a root reason why we are doing what we do. And connected to this, it is important to stress that when we instance the typical sectors, we are not implying that the sector examples are rigidly in just one category. Apple Inc., for example, may well produce many products that increase its clients’ autonomy, decision-making capabilities and time utilisation (Spirit); but they also improve customer status (Star – the caché of owning an Apple); situations (Searcher – the experience of owning Apple products); and competitiveness (Builder – their effectiveness demonstrated in many ways, including their interactivity). Indeed, some might argue that I have got it all wrong with Apple: certainly, Spirit is important for them – they have always been a sort of maverick, go their own way, kind of company – but perhaps their Creator or Expert dimensions are more important?

Whatever the reality is with Apple let others who are more informed decide. However, it is important to remember that motivators change over time: a snapshot of Apple in 1990, 2000, 2010 and now (2020) might reveal four very different companies from a motivational perspective. And what we are saying about Apple – which we have placed in the IT (Spirit) category – applies to all the sector examples: any particular case may appear in another motivational category at any point in time. The important thing to consider about any company is whether its WHY is aligned with its motivators

Finally, on Figure 4.5 I have identified three motivators as ‘Key’ and to do this I have selected one motivator from each of the three primary groupings of RAG. What I am highlighting here is what I consider root motivators in terms of the WHY. Obviously, Searcher is at the forefront because, as we have said, making a difference is quite directly a WHY issue; also, it is by far and away the most common motivator to be ranked first. Thus, top performing teams need to consider this issue as they develop their Remit.

Expert is ranked second. We are in a knowledge economy18; we cannot help but see that the old ways of doing things are rapidly becoming obsolescent, and that new knowledge, new skills, are driving change forward. Employees, as Figure 4.2 shows, want this and are motivated by it. In a way, then, for top performing teams this becomes a question of asking: What do we need to know and what skills do we need to have to be effective? Are we motivated to learn?

Finally, I have included the Friend motivator as Key, although unlike the Searcher and Expert, which are first and second in the rankings in Figure 4.2, it is apparently only 7th in importance for employees. The natural ‘Key’ motivator from the R type motivators would appear to be the Defender, which is ranked 4th and appears almost three times more frequently than the Friend as number one motivator in staff profiles. However, though security and stability may be a more deeply rooted motivator than belonging and friendship in terms of the Maslow Hierarchy, at a truly WHY level the Friend motivator is the one that holds the key to long-term success for a team (or an organisation). What is the reason for this?

Activity 4.4

Review the materials we have covered in Chapters 3 and 4. Think about what the Defender and Friend motivators are essentially about and then answer the question – why is it that for long-term team and organisational success we might be better-off keeping in mind the Friend motivator rather than the Defender? List some of your reasons.

The reasons are actually many and various. Firstly, it is good to remember what we established in Chapter 1 about what a team is. It had four characteristics, two of which are highly pertinent here (see Figure 1.1): namely, interdependency and strong belief. This latter characteristic specifically included a strong belief in the power of the team itself. Interdependency was about belonging and co-operation (Figure 1.2) and strong beliefs meant that the acronym T.E.A.M. was alive and well: Together Each Achieves More. Essentially, these are processes within the team rather than the content of what the team is striving to achieve. Therefore, top performing teams must cultivate that sense of belonging whether the Friend motivator is in the top three or not; and we know that it is frequently not.

Before considering some other reasons why the Friend motivator is a Key motivator for high performing teams, let’s consider a team map where Friend really is the lowest!

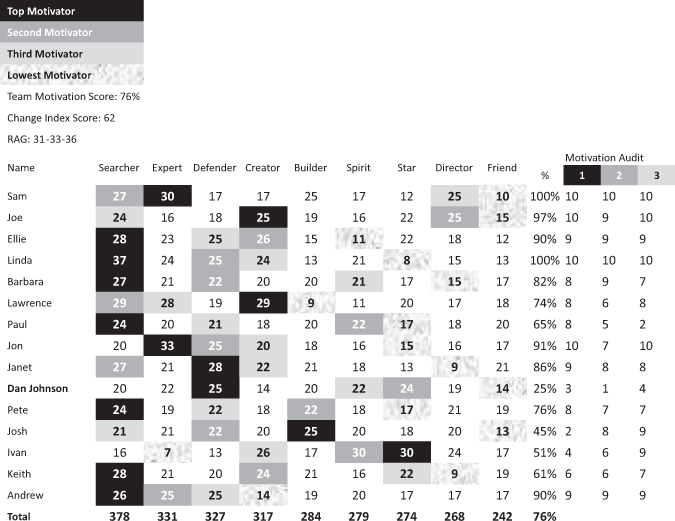

This Map is from a highly successful company with some 20 or so distribution premises in major towns and cities across the UK. This Map reflects one of the centres which comprises a retail outlet together with an IT sales force. In other words, it is predominantly a sales team with administrative back-up staff included in the profile.

Activity 4.5

Given our topic, what three germane things might you comment on, based on this Map?

First, the Friend motivator is not just the lowest motivator,19 but is by far and away the lowest motivator; at 242 it is well below the Director at 268, whereas the Director is only 6 points behind the Star at 274. Second, 4 people out of 15 have it as their lowest motivator and to compound the issue only 2 people have a score for the Friend of 20 or above (the ‘above’ here is only 21). Since below 20 means that the motivator has less pull or effect, we can assume that hardly anyone in this team is really bothered about belonging to it! Third, though the Team Motivation Score seems relatively high (76%), we have Dan who is only 25%.

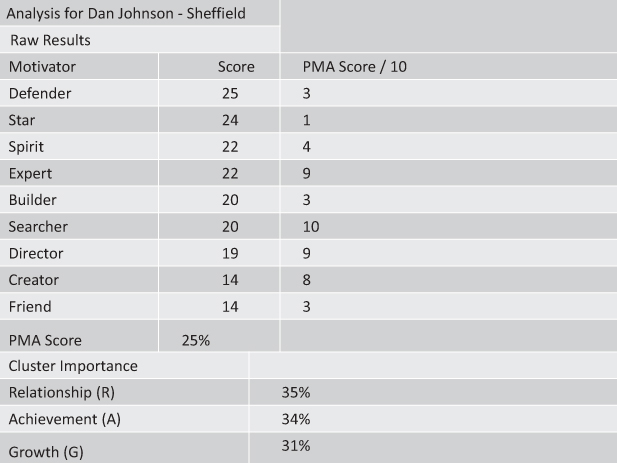

And why is Dan’s score significant? It is because of the PMA scores that go with it: we see that he may have a low motivational score partly because two (Spirit and Star) of his top three motivators are out of sync with rest of the team’s and, furthermore, we find that his PMA scoring for the top three motivators is very revealing: Defender (3/10), Star (1/10), Spirit (4/10). It is the Star score that is so startling: this is a Relationship motivator, like the Friend, and it involves perceived recognition, and he has scored it 1/10. At this point it is appropriate to seek more information in constructing our top performing team. In fact, we should look at Dan’s full 22 numbers, and doing so we find the following in Figure 4.7.

In building a top performing team by using motivational profiles, we now come to very advanced understandings of the motivators, and in particular, how they interact. Before commenting on it, try to work out for yourself what is going on here and why it is significant.

Activity 4.6

Study Dan’s 22 numbers in Figure 4.7 with particular reference to his PMA scores out of 10. To add a little context, Dan is a manager within this team and is in fact a high performing member of it. Given this, what then emerges from these numbers?

The PMA score of 25%, an exceptionally low score and one placing Dan in the Action Zone, is based on an algorithm which only takes into account the top three motivators. From a team perspective – though not from a coaching one – we don’t need to look at all the nine PMA scores. But here we see quite a remarkable thing: the top three motivators along with his remuneration (Builder 3/10) and sense of belonging (Friend 3/10) are clearly unmet. But – and a very big BUT – three motivators which are not so important to him are very clearly satisfied: his Expert motivator (9/10) is very high, his Searcher, making a difference for the customer is an extraordinary 10/10! And he is a manager, and he clearly feels that he is managing well, with his Director motivator at 9/10. Indeed, the overall scoring of the team also suggests he is managing well, since they are 76% motivated, and that suggests too that his levels of expertise are high.

But notice further this: two motivators that are not so significant to him (though Expert is 4th with a score of 22/40 and hence does have some traction for him) are the top two motivators of the whole team. In other words – and as happened – Dan seems to be performing at a high level in those very areas in which the whole team wants to perform; and, additionally, he has managing drives which more generally are lacking within the rest of the team. Thus, Dan seems to compensate for a profound lack of motivation in other team members.

What is this upshot of this? First, that until the Motivational Maps were completed, no-one had any idea that their manager was demotivated! He seemed to be motivated in those very areas in which they were too. And, equally, if belonging wasn’t important to him, neither was it to them. But that would be a misreading, for what the Map is actually revealing, and which proved true, is that either Dan was heading for a health or wellness issue as he struggled to conceal his true feelings – and motivators; or, Dan would be heading the stress off at the pass, as it were, by contemplating quitting the role. This proved to be exactly what he was thinking of.

But, still more, notice that Dan’s top two motivators are both Relationship- driven, even if Friend is not one of them (the R is highest at 35% in the Cluster Importance). The reality here is that Friend is a definite and dangerous hygiene factor for the whole team, but especially for Dan. In some curious way Dan is the motivational flip-side of his own team; he is the motivational ‘diversity’ that leads to the team having a massive strength and range. Yes, the team is all set to make a difference, prove their expertise to the customer, and so on; but Dan, first and foremost, wants to get things right, wants the systems to be efficient, and the processes smooth and predictable (Defender). This is a counter balance to the Searcher, and as the leader this was proving extremely effective. But there is a toll on Dan – which the scores show.

Indeed, the second motivator, Star, says it all: he scores his satisfaction with this the lowest of all, 1 out of 10, though it is Dan’s second most important motivator. It would be true to say here that precisely because Star is the most frequently identified lowest motivator, it can have a bad ‘rap’. By this I mean that the highly motivated Star can to other types appear ego-driven, narcissistic and rampantly self-obsessed. This is extremely unfair. Of course, a Star-motivated individual with low self-esteem will exhibit behaviour that is negative; but this is true of all the motivators – they have the potential when self-esteem is low to reveal their ‘dark’ or more negative side. But where we have someone with moderate to high levels of self-esteem the desire for recognition is healthy too.

And here’s the interesting point: where the self-esteem is low, there will not be enough recognition to go round, and so the Star-motivated type will withhold it from others. But where the self-esteem is healthy, the Star type will do what all the types do at that level: namely, project it out. The Searcher, for example, in wanting to make a difference, will seek out others and want them to make a difference too; or, the Expert will admire and seek out others with expertise. So Dan, in this instance, was a manager giving out recognition relentlessly to his staff, but his own craving for it, especially from his own company bosses, was not being met.

The top performing team here, then, is precarious, since its manager is not being fed with the motivational fuel he needs, and although belonging is not one of his motivators, Dan is quite clear that he isn’t being made to feel he belongs. It should not be difficult to see that there is a link here between the Star and Friend motivators; they are both Relationship driven, and moreover taking the time to enable Dan to feel he belongs is an important form of recognition. Feeding the one may well fuel the other. At the heart of this is understanding how the top team works within itself, and from outside too. In essence they are both about that fundamental way in which people – employees – feel important; we make them feel important, or not. To belong is to be important, and this links with Figure 1.1 again and interdependency; and to give recognition is usually to make someone feel they belong.

So, as I develop these points, we come to re-visiting Activity 4.4. Figure 1.1 gives interdependency and strong belief in the efficacy of teams as reasons why. We have partially covered aspects of the interdependency even at the motivational levels, and at the level of process. So far as belief goes, the belief is in T.E.A.M: an acronym20 standing for Together Each Achieves More. Belief creates expectancy and expectancy often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But perhaps as important as all these answers are, there is yet another: nobody, it is claimed,21 on their death bed says, ‘I wish I’d spent more time in the office’! On the contrary, virtually everyone says, ‘I’d wish I’d spent more time with my family, my loved ones and friends’. More generally, one is reminded of the philosopher Bertrand Russell’s observation22: ‘One of the symptoms of approaching nervous breakdown is the belief that one’s work is terribly important, and that to take a holiday would bring all kinds of disaster. If I were a medical man, I should prescribe a holiday to any patient who considered his work important’. The obsession with work – with the big A of Achievement – has a dark downside: stress, burnout and illness. People are one of the significant antidotes – through strong, positive relationships.

Activity 4.7 (Activity 4.4 revisited)

Now consider what we have covered so far. Think about what the Defender and Friend motivators are essentially about and then answer the question – why is it that for long-term team and organisational success we might be better-off keeping in mind the Friend motivator rather than the Defender? List some of your reasons.

The need for security is a normal and healthy human desire, so let’s be clear about that; but also I think if we reflect on it at any length, we can immediately see that it is the obverse side of that chronic and debilitating emotion we call fear. Ultimately, the lack of security prompts in us feelings of fear and we do everything in our power to counteract that fear. In terms of the Defender motivator, this counteraction tends to focus on creating stable structures, systems and processes in which results – future outcomes – become more highly predictable,23 thus reducing fear. This is good, so far as it goes, but we mustn’t forget that the emotion of fear can blind us to reality and lead to less than optimum decisions.

Conversely, whilst the need to belong is also a normal and healthy human desire, its obverse side (where not co-dependent) generates the emotion we call love. And love is the antidote to fear.24 So if we think about this from a top performing team’s perspective, the belonging (ie Friend) motivator is a kind of glue that holds people together, that resists fear and its weak decision-making, and provides an additional energy that comes from a belief and a commitment to each other.25

To expand this further: fear’s response to threat tends to focus on legislation, contracts, remuneration, property, pensions and all the other paraphernalia of ‘things’26 we seek to acquire; these can never provide true security.27 But belonging provides much deeper and long-lasting satisfactions. Hence people want to spend more time with those they love; and from a work perspective, they enjoy going to work! Moreover, not only do they like work because they like being there, but they also become more productive as a result. We need to remember that the essence of selling itself – and everyone, as Brian Tracy observed,28 is in selling whatever their role – is KLT29: the customer must Know you first, then Like you second, and then if they Trust you too, they will want to buy from you! It should be evident that the getting to like you is inherent in ‘liking’ someone, and when we belong we tend to like our associates!

As Dr Tom Malone observed,30 ‘The hard stuff is easy. The soft stuff is hard. And the soft stuff is a lot more important than the hard stuff’. This is the challenge, since we are dealing not just with motivation, which is itself part of the ‘soft’ stuff, but belonging and friendship and the glue that makes people want to work together and perform.

Activity 4.8

Imagine you have teams or even a team in which the Friend motivator is low or even the lowest motivator. Remember, that belonging will not seem important to them, but you know that without that sense of belonging, the team is likely to fragment or burn-out. What three or four Reward Strategies might you begin to adopt that could perhaps subtly bring in a greater sense of togetherness?

Context is everything, so what may work in one organisation may not in another. But some great ideas to consider are given in Figure 4.8. Try one or two of the ideas in Figure 4.8. Strive to make ‘What You Do’ a process that binds people together as well as being goal orientated. Further Team Rewards for the Friend are to be found in the Resources section.

Figure 4.8 Activating more belonging (Friend) for top performing teams

We move now in Chapter 5 to the third and final component of The Remit: Values we insist on.

Notes

1 And here we must put in a caveat in that in the last 5 years the wellness issue of employees has steadily risen up the priority chart of employer concerns, and with this has come the increasing recognition that people do not come to work just to make a wage.

2 ‘People work for money, but die for a cause’, said an anonymous CEO: cited by James Pickford, Mastering Management 2.0: Your Single-source Guide to Becoming a Master of Management (Pearson Education, 2001).

3 The word for this might be managerialism, which is defined as a belief in or reliance on the use of professional managers in administering or planning an activity.

4 Research done by Motivational Maps Ltd on a cross-section of over 100 sectors with over 13,000 maps in 2017 found an average of 39.5% individuals who had Searcher as their number one motivator. This is extraordinarily high; the second ranking motivator was the Expert where some 14.4% had it as their number one motivator. The lowest was the Star with only 1.1% having it as number one. Since Searcher can often be in opposition to Builder (but not always), the notion that simply leveraging money as a way of motivating staff, given the high levels of Searcher, is absurd. Indeed, these statistics alone suggest why there is such demotivation and disengagement in those organisations where a Builder mentality dominates all proceedings.

5 See Mapping Motivation, James Sale (Routledge, 2016), Chapter 4 for more on hygiene factors. Essentially, these are the lowest motivators which we tend to ignore, but which can become an Achilles’ heel in any enterprise we undertake, whether individually, at team or organisational levels.

6 Thanks here to Dr Shirley Thompson who did the data analytics to make this possible. See https://bit.ly/2wgUYct

7 Writing in the Financial Times, DHL CEO, Frank Appel, maintained that ‘when goals are predominantly financial, purpose is often lost’. He adds, therefore, two items to the bottom line: employee satisfaction and environmental targets. It appears to be working: staff surveys show workers feel more motivated than when he took over in 2009, and the company’s revenues have climbed from Euro 53bn in 2011 to an expected Euro 60bn in 2017. Cited in Patrick McGee, MoneyWeek, 2/2/2018.

8 David McNally’s expression perhaps nails why: ‘Growth and contribution are our primary mission in life’, from Even Eagles Need A Push (Penguin, 1994).

9 Simon Sinek, Start With the Why (Penguin, 2009).

10 As always with Maps, there are many more points that could be analysed and discussed. Here for example, that not only Builder, but also Creator also only appears once. Given the significance of Creator generally in terms of organisational innovation, that is an issue. As is the question of the motivators that appear which may be in opposition: Spirit and Defender is one good example. Readers may wish to reflect on what this might mean or betoken.

11 ‘There’s a tight coupling between results, compensation, and recognition’ – Gary Hamel, The Future of Management (Harvard Business School Press, 2007).

12 The complexity in today’s world cannot be overemphasised. A company like Macdonald’s might seem to be company which sells hamburgers, but in fact they make more money through their property; Coca-Cola’s prime business is ‘selling rights to other firms which make, bottle and sell its drink’. And Apple doesn’t manufacture a single phone! – Ed Conway, The Times, The Huge Profits in Thin Air, cited MoneyWeek, 14/02/2020.

13 ‘Put all your energy and resources into areas where you are substantially different from any rival’, Richard Koch, The 80/20 Principle and 92 Other Powerful Laws of Nature (Nicolas Brealey, 2014).

14 There is a spiritual sidebar to mention here. For in the Bible it is written that ‘man shall not live by bread alone’. The benefits of bread are clearly implied in the word ‘alone’ – yes, there may be something more important than physical bread, but bread certainly is necessary. If we complete the quotation – found in the Old and New Testaments (Deuteronomy 8: 2–3 and Matthew 4:4, King James Version) we find ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God’. This ‘every word … out of the mouth of God’ may be viewed as the ‘meaning’ or purpose of life; in other words, the higher calling. Put another way, we are not just animals who need to eat, but human beings who need to have a meaning in life. This correlates with our Searcher motivator and the highest level of Maslow’s Hierarchy where we self-actualise.

15 As G.K. Chesterton observed: ‘When it comes to life, the critical thing is whether you take things for granted or take them with gratitude’. From Irish Impressions (IHS Press, 2002), originally published 1919.

16 Including purchasing if only to get the vendor off our back or case!

17 See especially, Mapping Motivation for Coaching, James Sale and Bevis Moynan (Routledge, 2018), Chapter 7.

18 Perhaps one of the best examples of the exponential change that is engulfing us is referred to in Ross Thornley’s book, Moonshot Innovation (CrunchX Ltd., 2019) where he cites Peter Diamandis’ The Six Ds of exponential technology: Digitization, Deception, Disruption, Dematerialisation, Demonetisation, and Democratisation. These are drivers of change and basically they affect everything in our society and our world. As a ‘given’, then, the need for increasing expertise is almost self-evident.

19 And notice too that the order is Searcher and Expert as first and second; again, another example of the prevalence of these motivators.

20 For more on this see James Sale, Mapping Motivation, ibid., Chapter 6.

21 ‘Nobody on their deathbed has ever said “I wish I had spent more time at the office”’ – attributed to Rabbi Harold Kushner or sometimes to Senator Paul Tsongas.

22 Bertrand Russell, The Conquest of Happiness (1930; republished Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2013).

23 ‘The risk you should worry most about is the risk of not taking risks’, Richard Koch, ibid.

24 John Mark Green, for example, says: ‘If you want to tap into what life has to offer, let love be your primary mode of being, not fear. Fear closes us down and makes us retreat. It locks doors and limits opportunities. Love is about opening to possibilities. Seeing the world with new eyes. It widens our heart and mind. Fear incarcerates, but love liberates’ – https://bit.ly/30RWn5V

25 Of course, the inability to belong may cause fear as well, but I am highlighting here a contrast. It would be true to say as well that the need for security naturally leads to belonging, since we are never as secure as when we belong; so in that sense the Defender and Friend are complementary, not antagonistic to each other. But Maslow observed that, ‘In any given moment, we have two options: to step forward into growth or to step back into safety’. Defender activities where we step back and try to reduce insecurity via ‘things’ and processes may be thought of as feared based; whereas, Defender activities that step forward into building relationships, belonging, and teams, can be thought of as the way of love and growth.

26 For an extended treatise on the difference between people and things, see Chapter 8 of Mapping Motivation for Leadership, ibid.

27 ‘Remind yourself that the search for certainty won’t get you anywhere, so it’s important to consciously shift your attention away from that futile vortex’ – Beatrice Chestnut, The Complete Enneagram (She Writes Press, 2013).

28 Brian Tracy, Advanced Selling Strategies (Simon & Schuster, 1995).

29 Jeremy Marchant, Network Better: How to Meet, Connect & Grow Your Business (Practical Inspiration Publishing, 2018).

30 Dr Tom Malone, President and CEO, Milliken & Company, cited in 1001 Ways to Energize Employees, Bob Nelson (Workman Publishing, 1997).