Chapter 6

Interdependency and motivation

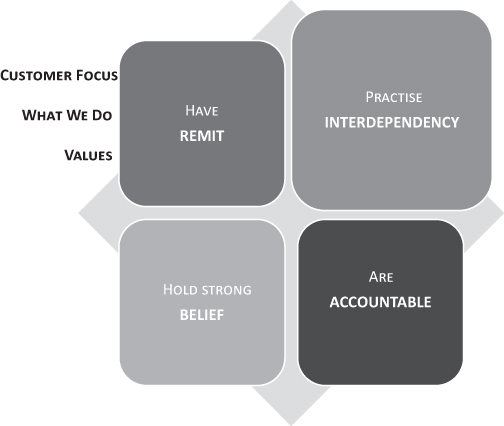

In Figure 1.1 we learnt about the four characteristics of a team. We detoured to look at the vital question of Reward Strategies in Chapter 2, but then returned to the first of these characteristics, The Remit, in Chapters 3, 4 and 5. As it turned out, The Remit was a huge area to cover, and we considered three specific aspects of it from a motivational perspective: see Figure 6.1. But now our attention shifts to the second characteristic, Interdependency, and its relationship with motivation.

Teams require interdependency as life requires oxygen1; it seems simple, but it’s not. There are so many factors working against interdependency.

Activity 6.1

What factors would you identify as working against interdependency within a team? If you had to rank them, what would be the top three factors preventing a top-performing team emerging?

There are, unsurprisingly, many factors that can derail a team. Some of these are external to the actual internal workings of the team: the recruitment process itself and then how new members are inducted (which may be externally structured), the reward structures and how appropriate and relevant they are, and perhaps crucially, at that point of interface between the external and internal, the leadership itself, which arguably is the single biggest factor and which if negative, undermines team cohesion. But internally, there are many other factors too: egoism, need-dependencies, personality conflicts, lack of knowledge and skills, and these factors can lead to very damaging behaviours. Behaviours such as restricting information, lying, breaking into sub-groups rather than solving problems together (sometimes called ‘paring’), in-fighting with win–lose situations within the group, flight and withdrawal, noise – speaking to be heard rather than to contribute, suppressing emotion and demanding logic (when emotions may be part of the problem). So the list goes on.

However, if effective leadership has to be the number one factor working towards creating a high performing team, then perhaps the number two factor is going to be the recruitment process. This is something the leader is usually, and should be, involved in. People leave, people retire or die, new projects arise, and so we are in a constant state of flux: who is going to be in this team? Who, whether that be an internal or an external appointment? The balance of the team is crucial. Remember what we said in Chapter 1: teams practise interdependency, not independency and not co-dependency! By this we signify that each person’s gifts, abilities and talents are needed, are necessary, to achieve the remit or the objective. Not too many people, so there is redundancy and bloat; and not too few, so that there is under-capacity to deliver. Not too many, not too few, just the right balance to achieve the goals.

And of course, alongside the recruitment go the Reward Strategies, for everyone who takes a job expects to be rewarded for it. So in a way, recruitment is like a tandem bike: we get the person in, and the rewards are on the second cyclist’s seat, helping to pedal and driving the whole cycle forwards! You will notice, then, that my two choices for creating interdependency are either external or on the threshold. The ‘threshold’ here meaning the interface between internal and external factors – see Figure 6.2. What is the third most important factor? Rooting out egoism? Stamping out personality conflicts? Ensuring information flows?

These are all important in their own way, but our view is that we have not included one vital factor that in our experience is so important, and this is an internal one. It is of course motivation. Whereas everyone has heard of ‘personality conflicts’, little thought has been given to ‘motivational conflicts’ and the damaging effects they have on teams. So our top three negative factors on team effectiveness range from the external to the internal factors, with that threshold point in the middle, leadership, being key. Figure 6.2 shows what this looks like.

The question of recruitment raises the further question of diversity in a team. Is this good or bad from a motivational perspective? Context is everything; there can be no easy or automatic answer. One contingency is always: what we are trying to achieve as a team? But as a general observation we would note that whilst everybody is claiming that ‘diversity’ is essential, what they mean by that is diversity of gender, race, religion, ability/disabilities, and other such categories; but what they clearly don’t mean by it is diversity of opinion or thinking!2 Indeed, thinking ‘differently’ too often invokes a penalty or outright group rejection.3 And just as thinking differently causes problems, so does motivational diversity; for, after all, diverse motivators drive us in unlike ways, which are often not acceptable if we feel (and feel strongly) differently!

And here’s a really important point to consider: it’s one thing having a different point of view, an alternative perspective on things, or what we might call a ‘thought’. But however serious conflicts in thinking are, they are never so serious as when emotions are involved, and this is exactly what the underlying motivators are. Most of the time our thinking is not rational ‘thinking’, but rationalisations of our emotional desires. As the philosopher Spinoza observed,4 ‘In a state that is not marked by emotion, one makes no progress in anything that is essential to mankind’. Actually, what this means is that the really big conflicts in teams (and elsewhere) are highly likely the majority of the time to have some motivational root, because when our motivations are ‘crossed’ or blocked, as it were, it immediately affects our motivational, our feeling state, and this is much more provocative than some intellectual disagreement about ends and means to which we are not attached.

Thus, the top performing team will understand motivation and motivators as a routine matter of course, whether they use Motivational Maps or not. But the Maps enable a much more exact and accurate way of understanding what is going on motivationally. Before we come to them, though, let’s consider recruitment again and what the high performance traits are that we are looking for in individuals we bring into a team.

Lou Adler,5 one the world’s leading recruitment experts, identified four traits or characteristics of individuals that we wish to recruit into any team.

Activity 6.2

What are the top four traits that you think you’d want in an individual recruited to a team that you were going to lead? And once you have identified them, which one do you consider the most important of all?

Figure 6.3 needs some unpicking to be clear about what we mean here. First, the most important trait of all is energy and energy-linked traits, such as drive, persistence and initiative. This should come as no surprise, since as we like to say, performance has three core elements: direction, skills/knowledge, and motivation. And if direction is the steering wheel of the car, skills/knowledge are the engine/chassis, then motivation is the fuel that enables the vehicle to travel at all.6 Adler neatly suggests that high performance comes down to: talent × energy2. Or, Figure 6.4.

Without getting into what ‘talent’ is – a highly ambiguous term7 –the fact is that energy is motivation. The first thing we need to establish at the recruitment interview is whether the candidate is highly motivated or not. If the candidate is internal, we ought to know the answer to that question, but we can easily blindside ourselves by rationalisations that override the importance of motivation. Rationalisations such as: Anna knows her stuff, or Bert’s been with us for 20 years and it’s his turn, or even Sunak won’t rock the boat, or everyone likes Frieda. As valid as any of these points may be, they don’t alter the central fact: motivation – high energy – is the driver of the best sort of performance that produces results.

If the candidate is external, then we have the problem of working out whether the application, the CV, the references, and most importantly, the interview performance, really reflect the energy levels of the candidate. Again, according to Adler, interview performance does not measure or even reflect actual performance on the job; further, Adler reckons that whether you like or dislike someone can constitute some 70% of the hiring decision! In other words, we regularly hire using criteria that are not related to performance.

Thus, to find out whether somebody is really energised, we need to ask questions that delve into their past performance in a slightly indirect way.8 We drill down, then, with repeated questions like: ‘James, tell me about your current role and what has been your most significant success to date’. Clearly, the interviewee is being asked to show what they can do, but the interviewer(s) know that any significant achievement is underpinned by high energy levels, which is identical to high motivation levels.

So, if that’s the case, then why not use Motivational Maps and go directly to the energy motivation question? This is not an either–or situation; rather, the Maps can complement and throw further and much deeper light on the candidate. Also, the candidate cannot second guess the meaning of the Motivational Map questions in the same way as they might the standard interview questions.

To get at this information, we need to tailor questions around the Map profile of the candidates; it is usually better if the interviewers do not discuss the actual Motivational Map of the candidate, but use it to consider how they respond to questions which we think we already know the answer to. This is a bit like the advice, often seen in cinematic court-room scenes, where the inexperienced lawyer is briefed by a more senior figure who instructs that one should never ask a question of a witness that one does not already know the answer to!

From the Map perspective there are four major areas to explore based on the candidate’s top motivator.9 Two of these major areas are revealed in Figure 6.5a.

The Root Questions may be introduced by a phrase such as ‘Looking through your application, I see that …’. Notice that one doesn’t say, ‘I see from your Motivational Map that you are a Searcher and so that making a difference must be important to you’ (and similarly for each motivator – adapt as appropriate). On the contrary (in as nonchalant and non-committal way as possible), we suggest that the application itself reveals that the candidate makes or wants to make a difference (and so on, for whatever is the number one motivator in the candidate’s profile). And then we seek for them to answer WHY this is so. Essentially, we are investigating, as a detective might, how self-aware the candidate is. Generally speaking, high self-awareness is positive and enabling10: the candidate is likely to be more responsive to change.

But then, we have the Check Questions. These are not asking why a motivator is important to a candidate, but rather WHAT they have actually done or achieved. This corresponds in Adler’s model to establishing past performance, since that is a likely indicator of future performance. As with the Root Questions, these too may be introduced by a short, non-committal phrase like, ‘I see that making a difference is extremely important to you. Tell me …’. And this question can be used iteratively: going back in time to roles prior to the one that candidate currently holds. Furthermore, the wording can also be modulated depending on which motivator (keep in mind, the top three tend to be the significant ones) we are focusing on. So, for example (and this is not prescriptive), we might say the top motivator is ‘extremely important to you’, but if we were dealing with their second highest motivator, we might say, ‘very important to you’, and the third motivator could just be ‘important to you’. In this way we vary how much importance to the motivator we are attributing to the candidate.

Clearly, these are crucial questions, for they are establishing three key things.

Activity 6.3

What do you think the three key things are that Figure 6.5a establishes for the interviewers of a candidate?

First, whether or not we know what really motivates the candidate; second, whether or not the motivator leads to actual outcomes; and, third, whether or not the candidate is genuinely aligned with their own motivational profile. This alone may almost be sufficient to separate the high performing candidate from the less valuable applicant, the wheat from the chaff so to speak, but given the expense of making a wrong hire,11 we may wish to dig even deeper. Therefore, still working with Motivational Maps, in Figures 6.5b (i), (ii), and (iii), we have developed two more powerful questions for each of the nine motivators that take our understanding of the candidate even further.

Figure 6.5b (i) The Creative and Block Questions for recruitment: Growth Motivators

Figure 6.5b (ii) The Creative and Block Questions for recruitment: Achievement Motivators

Figure 6.5b (iii) The Creative and Block Questions for recruitment: Relationship Motivators

This deeper digging involves two kinds of questions. First, is the Creative question. Keep in mind that from the Root and Check Questions we have uncovered the WHY and the WHAT. Now we are effectively considering HOW the candidate operates in their motivational field – how creative they might be in the post that they are applying for. This is essential because as is said in selling financial products – ‘past performance is not necessarily an indicator of future returns’. This is a get-out clause, for the truth is that past performance often is an indicator; a winner often wins,12 and a formula that has been successful can often go on being successful. But if we think about Figure 6.3, what we are also driving at here is the ‘Adaptability’ principle13: being creative, flexible and resilient, being able how to solve problems for the organisation that one is about to join, is central. We are, therefore, in these Mapping Motivation style questions covering (from Figure 6.3): Energy, Past Performance and now Adaptability. Is the energy of the motivator really driving achievement? These three types of question – Root, Check and Creative – answer this.

But still we have not finished, because there is an aspect of human nature that we need to take into account: namely, what happens when things go wrong? How do we respond to that scenario? And here we come to the subtlest parts of the interview questioning: The Block Question. That is, the question that explores what happens when our motivator(s) is blocked.

Activity 6.4

Reflect on your own top motivator, whichever one it happens to be. How do you feel when it is not being realised or met? And, even more so, how do you feel when it is not met over a prolonged period of time? What do you do? Think about this from your own work or role perspective or experience? Are you proactive, reactive, defensive, aggressive, passive, assertive or what? What changes occur in you when your motivator – or motivators – are not fulfilled?

I have spent some time getting you to think about this because it is vitally important. As the philosopher Arne Naess14 put it: ‘The road to freedom requires motivation through feeling …’. The freedom here is the freedom15 to self-actualise, to be all we could be, or to realise our destiny. Actually, then, if the motivators are not met, we feel constrained, our sense of freedom is impaired. We are blocked!

Furthermore, it is only when there is constraint and pressure that we truly find out what somebody is like; for anybody can be likeable and popular, or a good person, when everything is going well. But what are they like when the tide turns against them? In a sense the Block Question is also establishing the character16 of the candidate. So that the final Block Question is about finding how the candidate reacts to the situation when the top motivator (and this can also be used for the second and third most important motivators) is not being fulfilled. What did they do?

Here, however, there is an extra column which we call Block Responses. Basically, the Block Question is deliberately set-up as a closed question; in other words, it requires a Yes or No answer. Let’s take one example to see why. Take the Searcher motivator. Imagine this is the candidate’s top motivator.

Activity 6.5

Consider the Block Question for the Searcher: ‘Have you ever done work where you received very little or no feedback on how you were doing from anyone?’ There are two possible answers to this: either the candidate says, ‘Yes, I have been in that situation’ or they say, ‘No, I haven’t’. What are the issues to consider in either case? If you prefer, use the example of your own top motivator and substitute this question for the Searcher with the relevant one for you from either Figure 6.5b (i), (ii) or (iii).

So the column Block Responses in the three Figures 6.5b gives a shorthand summary of what we are looking for. Thus, if the answer is NO, this means the candidate has never been in a job or role where (using the Searcher example) there has been little or no feedback! Actually, that would be an astonishing feat, because one of the commonest complaints of all employees everywhere is that they do not receive sufficient feedback.17 But, it is not impossible: the candidate could be very young and relatively new to the job market, or could be a candidate who has only ever had one or two long-term jobs that have been incredibly fulfilling. There is also a third alternative, which is that the candidate has been in a role where the kind of feedback we are talking about is perhaps less relevant; for example, they have been a forester or ranger where they experience huge levels of individual autonomy and are supposed to get ‘lost’ for months at a time in their role. That said, all of this is relatively unlikely. Therefore, if the candidate says NO to this question, we have to ask ourselves a different question: Really? Is this likely? What is this candidate concealing? This is not to call them out directly, but it is to explore what this might mean. For example, is this person delusional about their role or their competence? Do they imagine they are doing such a perfect job there is no need for feedback? A follow-on question to them, then, might be: ‘What do you think about feedback? How would you benefit from this if you were to receive it?’ Notice now how we have switched from the closed question to more open ones; this is because we need to explore the issue in detail.

Of course, if the answer – and much more likely response – is YES: I have been in a situation(s) where I have received little or no feedback, then this is where we – the interviewers – want to be, and what we want to find out about; here is where we might learn about the candidate’s character, persistence, growth and creativity. How did they respond to the absence of something their motivator indicates they crave?

The follow-up to YES is, then: What did they do (that is, realising that they weren’t getting any meaningful feedback)? Again, looking at Activity 6.4, how did they respond (according to their own account of themselves)? Does it sound like they were proactive, reactive, defensive, aggressive, passive, assertive or what? And once they have answered that question, we can press them still further: How would they respond if they were working here and didn’t receive the kind of feedback they initially envisaged and desired?

This follow-on question is very difficult to answer, especially if their previous answer is hardly convincing; at this point, the candidate will resort to clichés or generalities which show they have no real grasp of the issues, or internal resources, to be able to deal with difficult situations.

If we summarise where we are, we have reviewed interdependency as a core attribute of teams and found that recruiting the right people in the first place is of the first order of importance.18 Furthermore, we have also discovered that using the Mapping Motivation system in the recruitment process can cover many bases: namely, establishing high levels of energy, compelling past performances, and demonstrating adaptability; three key criteria identified by Lou Adler. What we haven’t dealt with is Point 2 of Figure 6.3: team skills.19

Clearly, these are very much at the heart of interdependency. In our previous books20 we have covered many aspects of this, as our Preface to this book also noted. What we are looking for from the recruitment perspective is staff who can motivate, persuade, influence and negotiate with others, who can cooperate, collaborate and share an enthusiasm for The Remit, who can work together as a real team in other words. And this means, beneath the surface, high levels of self-esteem, self-confidence, emotional maturity, and the ability to take full responsibility for one’s own actions. No blaming, no projecting, no denial; no passing the buck, then, no organisational politics, no playing the system. Getting the job done! Wow! That’s a big ask.

The standard – and effective (if done well) – way of establishing these qualities without using the Motivational Maps is by drilling down on team related questions.

Activity 6.6

What are ‘team related questions’? If you wished to establish whether a candidate was a team player or not, what sort of questions might you ask them? What would be the three most important ones?

The important thing here is to drill deep rather than accept superficial answers and simply move on to the next question in the list. There cannot be a definitive set of questions, but we like these three. Ask them, and ask for three examples in each case. Most people can drum up one answer, but it is going deeper than ‘one’ answer that reveals what is really going on. If necessary, go back several years and into previous roles or jobs. And feel free as you do this, to get the candidate to specify exactly what their role in the team is, who they answer to, and what results they have actually achieved.

As you ask these questions and study the answers to them, you will certainly find out about their team skills; and along the way their character, personality and possibly their fit into the culture of your organisation generally, and the team specifically. Quite a lot, then, may be revealed!

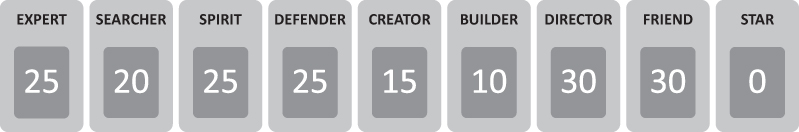

But here we come to where motivation and the Maps help us even more. For let us ask this question: can Motivational Maps identify high performing teams even without including the scoring? Clearly, if we include the scoring, then we know that high motivational scores tend to be correlated with high performing teams. This is also true of the individual – a point we will return to. But what about if we don’t know the scores?

Activity 6.7

Why would we want to consider whether a team were high performing or not without looking at the scoring? Why not simply use the scoring as our guide?

The answer is that by checking via another Map methodology we increase the chances that we are going to get the correct answer. Truth is, just looking at the scores can make us lazy and too reliant on a simplistic equation: high motivation equals high performance – job done! But teams are made up of human beings, and human beings can be subtle and ambiguous, and not all is what it appears. Hence, the need to approach this issue in another way.

The starting point of considering whether a team is functioning at a high level is the profile of the organisation itself. Here we are going to take a real life example from an anonymised FTSE 250 company.

Figure 6.7 shows the profile of a company employing several hundred people. It shows the rank order of the whole company’s nine motivators. Whereas we are not going, initially, to know the motivational scores of the teams, it would be helpful to know how the organisation is doing motivationally: 77%. With so many hundred Maps aggregated, this represents a highly accurate benchmark score – accurate, that is, at that moment of time.

Activity 6.8

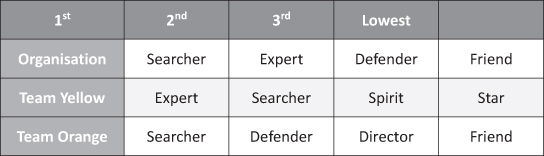

Figure 6.8 shows two teams from the same company. Both teams have the same function within the organisation, which is mainly customer service. They have approximately the same size too: team Yellow has 6 members and team Orange has 7. But the motivational scores have been removed. Their motivational scores do correlate with their respective performances; but without knowing them, which team – Yellow or Orange – do you think is high performing, and which less so? And what reasons do you have for this?

The first thing to study is how the teams compare with the company overall in terms of their top three motivational profile.

Inevitably, it must be the case that anything we say here is tentative. But the first thing to note is that Team Orange is more aligned with the Organisational profile than Team Yellow. This is particularly important regarding the top motivator, Searcher, which they share. It is particularly important because the top motivator is, by definition, the most important; but it is also significant because this motivator is very driven to make a difference for the customer – which both units are seeking to do. Since we know the organisation is highly motivated at 77%, the more correlated a team is with it, the more likely they are to be high performing. Why? Because they are aligned – fit – motivationally; their energies are moving in the direction of the same stream.

A secondary point would be that whereas the Organisation and Team Orange both share Friend as their lowest motivator (again in sync, as it were), Team Yellow has Star. This might indicate that there is a lack of recognition either for the team or certain members within it.

Figure 6.9 Comparison: organisation with Teams Yellow and Orange

Finally, although doubtless there is more to be mined from the details, there is the fact that Team Yellow has the Spirit in its top three, whereas Team Orange has the Director entering the fray: Spirit and Director are conflicting motivators, sending one in entirely different directions. But given how low Spirit is organisationally (ranked sixth – Figure 6.7), this kind of autonomy and its functioning doesn’t seem desirable, or what the organisation is really about. Indeed, the combination of the Searcher/Defender suggests a very process driven approach to customer service, and the Spirit motivator is not that.

And based on these musings, we find we would be right if we look at the actual scoring of the team maps.

Activity 6.9

Consider Figures 6.8 and 6.10 together. From it you will be able to see how each individual feels about their top three motivators. For example, team member A is 80% motivated, and he scores his top three motivators as follows: Defender (7/10), Searcher (10/10) and Expert (9/10); and so for the rest. When you have studied this, give three reasons, based on the numbers, why Team Orange is high performing and Team Yellow is not.

First, and mostly obviously, the team scores themselves indicate a fundamental difference in energy: Team Yellow on 59% is in the Risk Zone, whereas Team Orange at 85% is in the Optimal Zone. This is highly significant on an individual level, but is even more so when compounded at team level. Team Orange is thriving energetically and this will certainly be reflected in its results.

Second, the variation in scores, or the range between the highest and lowest, is far more marked in Team Yellow (88–10, or a range of 78 points) than in Team Orange (100–66, or a range of 34). This suggests far greater stability and consistency in approach, and this in turn suggests better management.

Finally, we can look at the specific individual scores. We note that the lowest motivated person in Team Orange is person H, who is only 66% motivated, whereas in Team Yellow we have two people, B and E, who are, respectively, 26% and 10% motivated; very low scores indeed. Without these two characters the average would be approximately 75% as the team score; but that’s still well below Team Orange’s 85%. However, a subtler overview might consider the actual individual audit scores.

A score of 6/10 we regard as average. In Team Orange there are only two scores below 6/10: H scores 3/10 for their third motivator (Star) and I scores 1/10 for their second motivator (Builder). Actually, I’s overall scoring pattern requires comment, and we will return to this in a moment. But first, if we look at Team Yellow, we have B, who has scored their first and third motivators 1/10 (Star, Friend), C who has scored their second motivator 5/10 (Spirit), E who has scored all three motivators 1/10 (Searcher, Expert, Defender), and F, who has scored their third motivator 5/10 (Builder).

If we therefore now return to Activity 6.9, we see that whereas in Team Orange we only have two team members with specifically low motivator fulfilment, in Team Yellow we have four; and the low scoring is far wider ranging and more acute.

But in doing this analysis, we get extra information too: there are only two motivators that recur as problematic across the two teams: the Star and the Builder. Are people within teams getting enough recognition? And how does remuneration compare across the industry sector? This is an important point that might help Team Orange sustain its already high level of motivation and performance, and address some festering issues within Team Yellow which are holding it back.

Finally, there is one extra point to address: the profile of team member I. Whilst the motivational score overall is high, 82%, the numbers that make it up are a cause for concern. Indeed, if this person were a candidate at recruitment, then the fact of being 82% motivated might not be taken at its face value. The reason for this is the numbers themselves, see Figure 6.11.

Activity 6.10

Look at the numbers for I’s profile. What strikes you as ‘odd’ about them?

One can never emphasise enough that Motivational Map readings should always be tentative; we are dealing with an inherently ambiguous property, and because motivations can change almost overnight in some circumstances, one must not make definitive comments. But what the motivational profile does is point to possible explanations or areas of interest that might affect how an individual or a team might perform in the long run.

What is ‘odd’ in Figure 6.11 is two-fold. First, that the nine motivator scores are all multiples of 5. Usually, when this occurs21 we have potentially a false or misleading result. And secondly, that the Map will certainly be an extreme one: that is, the range of scores will be extremely wide.22 Given that the average range from top to bottom score is about 8 points, here we have a range of 30 (0–30).

We recommend that anyone doing the Map does not agonise for too long by trying to second guess their own answers, but that is quite different from dashing down extreme and polarised scores: every answer must be 5–0 or 0–5 with no shades of grey in between. So, how likely is this to be an accurate representation of one’s real motivators? It’s possible, because there are really extreme people out there, but it is not likely, and so in typical Motivational Maps fashion, and especially at the interview stage, this needs examining carefully.

If, then, we want a top performing team, here is an issue for Team Orange: it is high performing, but the individual, I, may not be fully aligned with what is going on, despite an apparently high score of 82%. In Team Yellow we have the obvious fact that team members, B (26%) and E (10%), need attention, for their scores are dragging down the whole team. But sometimes the high scores too need attention. The percentage scores are important, but must not be considered in isolation.

Finally, keep in mind that the motivational profile may indicate the existence and practise of team skills, although it does not specify what they are or may be. In other words, high levels of motivation frequently presuppose the acquisition of whatever is needed to deliver the outcomes because such energy drives The Remit. Simply training people on ‘team skills’ is counter-productive if they are not motivated in the first place. In a top performing team motivation precedes the acquisition of skills.

We have, therefore, now looked at some key motivational aspects of interdependency and how teams cohere through motivational recruitment and also via the motivational profiles themselves. Our next chapter considers Belief and Top Performing Teams.

Notes

1 And additionally, as the Motivational Mapper, Paul Kinvig, likes to say: ‘Motivation is like air; it’s terminal when it’s not there’.

2 A scathing comment reflecting on this issue came from Ben Shapiro: ‘“Diversity is our strength” is Orwellian claptrap coming from people who can’t handle a memo that says that men and women are different’ – Ben Shapiro, editor Daily Wire, quoted in the MoneyWeek, 12/8/2017. Shapiro was indignant that a Google engineer had been sacked from expressing what he saw as a non-controversial point. The sacked engineer posted an internal memo called Google’s Ideological Echo Chamber. The text and Google’s response can be found at https://bit.ly/39hNzHq.

3 Hence the phenomena of ‘groupthink’, which we have commented on before in our previous books; the subtle pressure that ultimately leads everyone to agree and think the same. See Mapping Motivation for Engagement, James Sale and Steve Jones (Routledge, 2019), Chapter 4. Also, Group-think, a concept outlined by Irving Janis, Victims of Groupthink; a Psychological Study of Foreign-policy Decisions and Fiascos (Houghton Mifflin, 1972).

4 Cited in Arne Naess, Life’s Philosophy (The University of Georgia Press, 1998). Naess himself percipiently notes that ‘Reason loses its function where there is no motivation, and motivation is absent where there are not feelings either for or against’. Donald Calne expressed this another way: ‘The essential difference between emotion and reason is that emotion leads to action while reason leads to conclusions’ – see https://bit.ly/2r019eS. It should be clear from this, therefore, that motivational conflicts – because they are inherently energised – are a major source of conflict within organisations, teams and between people.

5 Lou Adler, Hire with Your Head: A Rational Way to Make a Gut Reaction (Wiley, 1998).

6 This formula for performance runs through all our work, but especially see: Mapping Motivation, ibid., Mapping Motivation for Coaching, James Sale and Bevis Moynan (Routledge, 2018), and Mapping Motivation for Engagement, ibid., Chapter 1, for an advanced formula or ‘take’ on these ideas.

7 The seminal book on this topic, The War for Talent, Ed Michaels, Helen Handfield-Jones, and Beth Axelrod (Harvard Business Press, 2001), perhaps unsurprisingly fails to define ‘talent’, saying: ‘A certain part of talent elude description: you simply know it when you see it… We can say, however, that managerial talent is some combination of a sharp strategic mind, leadership ability, emotional maturity, communications skills, the ability to attract and inspire other talented people, entrepreneurial instincts, functional skills, and the ability to deliver results’.

8 Asking any candidate: Do you have high levels of energy/motivation in your work? Is, of course, only going to elicit a broad grin and the answer, Yes!

9 In fact, this is a simplification for the sake of space: the second and third ranking motivators can also be explored in this way; and it is also prudent to investigate the lowest motivator and what this might mean for the individual’s performance in a given role, and for the team cohesion.

10 One scarcely need prove this point, since there is so much evidence around it, and it also seems like common sense, given a moment’s reflection on one’s own experiences. Psychiatrists and psychotherapists Jeremy and Roz Holmes in their book The Good Mood Guide (Orion, 1996), express it powerfully thus: ‘Self-observation is in itself transformative, in an extraordinary way’.

11 According to BreezyHR, the real cost of a bad hire is always going to be a little different depending on your business. But citing data from the US Dept of Labor, The Undercover Recruiter and CareerBuilder, they give three cost scenarios: 1. The cost of a bad hire can reach up to 30% of the employee’s first-year earnings; 2. Bad hires cost $240,000 in expenses related to hiring, compensation and retention; 3. 74% of companies who admit they’ve hired the wrong person for a position lost an average of $14,900 for each bad hire. See https://bit.ly/3aMM3Pd.

12 Although, of course, we acknowledge that expression made common in popular music: the ‘one-hit’ wonder!

13 This requirement for ‘adaptability’ has become a virtual movement in the last decade or so. In 2019 LinkedIn ranked it the fourth most desired soft skill companies want (https://bit.ly/2WZyKXr). In 2018 Accenture said that ‘Adaptability to become top skill in 10 years’ (https://accntu.re/3dJKEeb). And the Institute for the Future in 2018 claimed that ‘Adaptability… essential skill for the future’. See: AI Forces Shaping Work & Learning in 2030, Report on Expert Convenings for a New Work + Learn Future, October 2018.

14 Arne Naess, ibid.

15 And it is not the Spirit motivator per se; to take one example, the Defender motivator itself will feel ‘free’ or freer when the motivator of security is met. This seems a contradiction almost, but it is not: a motivator we want, even if it seems to constrain us, enables us to feel freer – certainly of the anxiety caused by not having it met.

16 Thomas Merton wrote, ‘Souls are like athletes that need opponents worthy of them, if they are to be tried and extended and pushed to the full use of their powers’, The Seven Storey Mountain (Harcourt, 1998).

17 A recent article in Forbes magazine suggested that 65% of employees want more feedback! That’s a large number. Victor Lipman, ‘65% Of Employees Want More Feedback (So Why Don’t They Get It?)’, 8 August 2016, https://bit.ly/2JDfWW1

18 Jim Collins, From Good to Great (Random House Business Books, 2001) makes the point that it is far easier to recruit the right people on the bus before you start the journey than to discover once you’ve started that you have the wrong people.

19 For more on team skills and specifically the Five Elements model of team skills, see Mapping Motivation for Leadership, James Sale and Jane Thomas (Routledge, 2019), Chapter 4. Also, see Chapter 6 of Mapping Motivation for Engagement, ibid., for four specific team skills of the Engaging Manager: cognitive/perceptual, interpersonal, presentational, and motivational.

20 Specifically, Mapping Motivation, ibid., Chapter 6 looked at motivation and teams; Mapping Motivation for Engagement, ibid., Chapter 6, considered the role of the engaging manager for the team; and Mapping Motivation for Leadership, ibid., Chapter 6, explored how leaders build teams and how to create team agreements.

21 One notable exception to this rule is the extremely rare (three occasions in over 70,000 Maps) when the nine motivators are all equally scored: all 20/40. This is a multiple of 5, but the comments in the text do not apply to this situation. The score seems to be accurate, and the individual is lacking in decisive motivators; the role of the coach or manager here is to help them set effective targets or goals that they can get behind, given their generally weak drivers. See Figure 7.7 for a real example.

22 Alongside the wide motivational scores, the satisfaction scores too are extreme: 10–1–10, suggesting he is totally satisfied with some motivators and totally unsatisfied with others. This necessitates looking at this individual’s complete 22 numbers: do they all exhibit this tendency? And yes, they do: his satisfaction scores in the rank order of his motivators are: 10, 1, 10, which we already know, and then 10, 5, 5, 10, 5 and 10. The ‘odd’, not multiple of 5, is the second motivator, but overall this doesn’t obviate the impression that this person is seeking to make an impact or statement in doing the Map. As we said before, this needs careful examination.