CHAPTER 7

Managing Risk and Opportunity

Integrating sustainability topics into project risk management is critical to effective risk management. One thing that makes sustainability risks more complex to manage than traditional project technical risks is that they often involve external factors that lie outside the project's direct control and require collaboration across departments. This does not mean that sustainability risks cannot be understood, managed, and mitigated. It simply means that project teams must pay close attention to risk management processes and procedures to ensure they are capturing the right risks, honestly assessing the impacts, and developing proactive management plans.

Effective risk management is becoming more important to:

- De-risk projects to support project financing and insurance as more major projects run into development and construction issues

- Manage the rapidly changing impact of social media and connectivity that makes anyone with a cell phone a potential investigative reporter and allows any community to assess how your organization has acted on other projects around the world

- Managing the potential physical, political, and financial impacts of a changing climate

- Understanding the impacts of social changes from demographics of an aging population to migration and pandemics

The benefit of a good risk program is that the project runs more smoothly, and the project team can focus on the challenges of creating a better project rather than running from one crisis to the next. Taking the time to complete a risk register and risk mitigation plans as early as possible in the project, and committing the effort required to monitor and update the plans regularly through project development are keys for project success.

The risk management process can be used to identify opportunities that could improve the project by reducing environmental impacts or support the local community. These can even reduce the total cost of ownership and create better projects.

The risk management process includes:

- Setting the stage to evaluate risks by reviewing project information, goals, and objectives

- Describing what success looks like

- Understanding the level of impact and likelihood that are important to the project

- Identifying and assessing risks in a workshop that brings a wide range of project team members together

- Developing risk management plans that identify the risk management measures available, who will be responsible for the management, and how often the risk will be reviewed and reassessed

This chapter describes some of the standard approaches to risk and opportunity management. Your organization may use a different approach, but the changes and adaptations that can integrate sustainability into the risk management process that are explored here are still relevant.

7.1 Risk Workshops

One of the most common approaches to developing risk management plans for a major project is to hold a series of risk workshops that bring together key project team members for a focused discussion to review key project risks, identify their severity, and develop risk management plans.

Getting the Right People at the Table

Risk workshops leverage the wisdom of crowds: the collected knowledge, experience, and insights of the project team. In order to have the most successful risk workshop you need to ensure that there is a diverse collection of wisdom in the room. Doing a risk workshop with a team of civil engineers, for example, helps to identify risk associated with structures and roadways but probably does not help address risks associated with greenhouse gas emissions, workforce training, or project impacts on the local community. Some key members of the project team who should be invited include:

- Owner's representative

- Engineering design teams

- Procurement

- Construction

- Operations

- Sustainability

- Finance

- Environmental management

- Community relations

- Government relations

- Human resources

- Health and safety

The risk team can be augmented by external development partners and contractors on the project, who can provide further insights into local issues and challenges. This might include the impact assessment (IA) consultant who is supporting the project approvals process, or a local contractor who is employing local workers and executing skills development programs.

Also consider using a skilled risk facilitator who can organize the workshop and guide the discussion. An external facilitator can ensure that information is provide ahead of time, risks are properly documented, each group is given time to present and discuss risks, and everything is documented for future management and tracking of project risks. Part of a good facilitator's job is to make sure that everyone is given the same opportunity to contribute. Risk workshops can easily become focused on a particular type of risk. At the end of the workshop you could end up with a large number of small risks associated with one topic and not enough risks in other areas. It is more efficient to identify a set of risks and set a follow-up session (such as a hazard assessment session for design safety risks) as the risk management action to allow the broader session to continue.

Be Prepared

Project risk workshops can often take several days to complete. While this is an important investment in good project management, maximizing the efficiency of these workshops helps the team to focus on the managing key risks rather than spending time reviewing background material. This is especially true for sustainability risks that tend to be project-location specific. Many project team members may not have a clear and full understanding of local conditions and challenges. In order to improve the efficiency of the risk session, the host or facilitator can provide supporting documentation for the risk team to review before the session. Some documents that could support the risk workshop include:

- Project Execution Plan (Chapter 5)

- Project Charter (Chapter 5)

- Output from PESTLe and Sustainability Activity Model tools (Chapter 4)

- Community concerns collected from stakeholder engagement (Chapter 6)

- Organization policies and goals (including the Sustainability Policy) (Chapter 5)

- Community agreements

- Summaries of the Impact Assessment or major project approval submissions

Depending on the stage of the project and the team's experience with the project location, there may be a need to execute additional research to support the risk workshop. For example, if the project is in a country that the project team has not worked in before, then researching the political, economic, and cultural aspects of the host country before the risk workshop will help to identify and assess local risks. Some possible sources of information include:

- Global Risk Reports

- Country resources

- National and regional newspapers

- Social media

- Local consultants or community relations teams

This research can be used to prepare or update a Project Risk Checklist that is provided to the team prior to the workshop. Advance preparation would help stimulate discussion on country and local risks that the team may not have previous experience with.

Setting the Stage

The first step in a risk workshop is to set the stage by establishing a baseline of understanding for the entire risk team. This includes reviewing the core background information for the project such as the project charter, to ensure that there is agreement on the overall project goals. If integrating sustainability into major projects is a new concept for your team, then taking time early in the risk workshop to review the sustainability goals can help to create a focus on environmental and social risks and avoid debates about the purpose of sustainability throughout the workshop.

Setting the stage should also involve defining what success looks like by turning high-level project goals into more concrete objectives. For example, the high-level goal of delivering the project on-budget could be defined by including the current target budget. The statements defining what success looks like should be captured and agreed to by the team before continuing with the risk workshop and can provide a reference point for the team to help resolve debate or focus discussion.

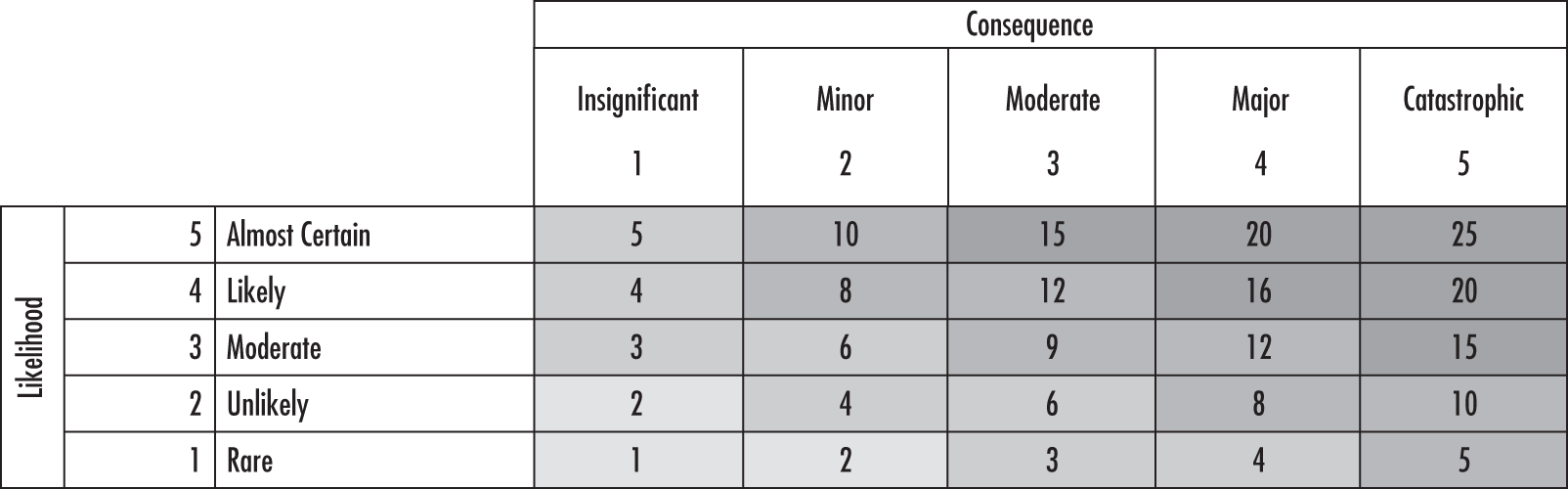

The next step before discussing specific risks is to establish definitions for the impact and likelihood of specific risks. The potential severity of a risk is defined as potential damage that a risk could create (impact) times the probability that the risk could occur in the defined time frame (likelihood). As per the following equation:

Likelihood

The risk team should evaluate a scoring system for the likelihood portion of the risk occurrence that establishes a range of outcomes from a rare occurrence to something that is almost certain to occur. An example of a range of risk likelihoods is shown in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Risk likelihood definitions.

| Score | Likelihood | Definition |

| 5 | Almost Certain | Already occurring or certain to occur |

| 4 | Likely | >25% |

| 3 | Moderate | 5–25% |

| 2 | Unlikely | Low probability <5% |

| 1 | Rare | <1% |

When assessing risks, one way to define the likelihood is to look at other projects in the region, organization, or industry to see if the risk has occurred in other projects and how often it has occurred. For example, if the project is located in a region where safety statistics have typically been poor, then the likelihood of a safety risk would be ranked higher than it might be in other regions. This doesn't mean that safety risks are accepted by the project but, by raising the likelihood and severity of the risk, the team can increase efforts to manage safety risks in order to meet project goals.

Impacts

The next step is to create a range of potential impacts for risks. Since there are a number of different types of impacts to a project, the impact needs to be assessed in terms of traditional project risks (like financial and schedule) as well as for other potential impacts (like people and safety, environmental, and reputation/community support). Each project is different, and the team will need to define impacts that are specific to the project goals and objectives. An example of risk impact definitions is shown in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2 Example of risk impact definitions.

| Score | Impact | Financial | Schedule | People/Safety | Environmental | Reputation/Community Support |

| 5 | Catastrophic | >$10 million | >6-month delay |

Serious injury Large layoffs Unionization |

Large-scale spill Habitat damage Enforcement action |

Lawsuits Loss of approvals Protests |

| 4 | Major | $3–$10 million | 3- to 6-month delay |

Lost time Injury Staff quit Layoffs |

Permit delays Wildlife deaths |

Negative global press, Work stoppages |

| 3 | Moderate | $1–$3 million | 1- to 3-month delay |

Medical attention Staff unhappy High absenteeism |

Regulatory fine Multiple small spills |

Negative local press |

| 2 | Minor | $300k–$1 million | 1-week to 1-month delay |

Minor injury Formal complaints |

Regulatory warning | Formal complaints |

| 1 | Insignificant | < $300k | <1week | Complaints | Small spill | Complaints |

Assessing Nonfinancial Risks

Nonfinancial risk impacts can create a lot of debate during risk workshops. So it is important to spend time up front to understand how to balance the financial and nonfinancial impacts and establish definitions that everyone can accept prior to digging into the risk evaluation.

One way to connect financial and nonfinancial risks is to correlate the nonfinancial impacts back to financial impacts. In some cases, the correlation will be direct. In other cases, the financial impact may need to be calculated by estimating the financial impact of another type of risk impact. For example, a large fuel spill could create a direct financial impact from cleanup costs, plus the indirect cost of a one-week schedule delay during construction. The financial impact would be calculated from expected standby rates for equipment and labor. Do not get too concerned about the accuracy of the correlations as no risk estimates are accurate, but a correlation can help to align the risk impact definitions.

Some techniques to correlate nonfinancial impacts and financial impacts include:

- Health and safety incidents have costs for lost time, investigation, and corrective actions.

- Risks associated with employee morale can be assessed by looking at turnover rates, absenteeism, and the cost to hire and train new employees or contractor workers.

- Lack of skilled employees can be assessed as the cost of construction delays or accidents.

- Engineering design problems can be assessed by the cost of rework,

- Environmental impacts like spills can be assessed by the cost for spills and potential fines that might be applied.

- Loss of community support can lead to delays in approvals, which has a direct impact on the project schedule and on the project's net present value (NPV).

Working with finance and procurement to understand the potential cost of schedule delays at each stage of the project can provide a good basis for the project team to assess project risks, especially related risks related to sustainability, which may seem “soft” to a highly technical project team.

This approach is not foolproof and should be reality checked so that the correlations do not become too focused on the financials. For example, the financial impact of fatality onsite during construction can be calculated and applied as a financial rating in the risk impact table but should not be used to reduce the impact to anything less than catastrophic.

7.2 Project Risk Register

Once the stage has been set and everyone is ready to discuss the project risks, the risk workshop can continue with the development of the risk register. The risk register is used to document possible risk events, document the potential severity of risks based on current project plans, identify risk management plans that can reduce risks, and then document the revised project risks with the management plans in place. A well-structured risk register will also identify who is responsible for ensuring that risk management is in place, and for documenting the timing needed to develop the risk implementation. This allows the project team and leadership to receive regular updates on the status of risk management plans and any updates to potential project risks.

Identifying Risk Events

The first step in developing the risk register is to identify risk events that could impact the project. Risk events are typically written in direct language that follows this format:

This “risk event” results in that “consequence.”

Examples of that language might be:

- A major diesel spill during construction refueling results in a one-week schedule delay.

- A severe storm with high winds damages construction cranes, resulting in expensive repairs.

- Concerns in the community that the project may not provide jobs results in a one-month delay in project approvals.

In some cases, the same risk event could have more than one consequence or outcome that need to be captured. These can be captured in one event if the same risk management plan is likely to be effective or can be split into more than one risk event. In general, it is better to initially enter only one risk event in the risk register during the risk identification process and then split the risk event into more than one event, if necessary, in the future. Using the diesel spill example, the event could capture additional consequences and be written as:

A major diesel spill during construction refueling results in a one-week schedule delay, a $100,000 cleanup cost, and increased scrutiny from the environmental regulator.

Brainstorming Risks

The risk workshop brings together a wide range of people with very different knowledge experiences that can be leveraged to identify and understand the diverse risks that the project team will need to manage. Creating an environment in the workshop that promotes sharing of ideas and a respectful discussion of different types of risks is essential for a successful session. Like other types of brainstorming, there are rules that everyone should understand and follow for a successful workshop, including:

- Creativity and free expression of ideas is encouraged.

- Criticism is not allowed.

- Positive feedback and improvement of ideas are welcome.

- Quantity is important as the more risks identified, the less likely it is that a serious risk will be overlooked.

These rules for engagement are especially true when dealing with sustainability risks that can often create frustration. Often, technical teams are typically pragmatics and focused on moving forward with design. Or some individuals might bring their political views to the table. For example, an open discussion of the risks associated with climate change, the potential for climate regulations, or carbon taxes can be challenging if attendees do not agree with climate projections or the need to reduce carbon emissions. In this case, risk management provides an ideal structure for dealing with a complex issue like climate change. The team doesn't need to agree on the science of climate change to evaluate the likelihood and impact of a severe storm event during project construction. A climate skeptic might choose a lower impact and likelihood score, but the potential risk can still be documented and tracked. The team might not like the idea of a carbon tax, but the likelihood of a tax being applied can still be assessed and the impact calculated in potential financial cost to the construction and operation of the facility.

Pre-Mortem

One interesting approach to generate potential risks during brainstorming is to perform a “pre-mortem” exercise. Through the pre-mortem process, the team imagines that they are at the end of the project and hypothesizes what went wrong or what went right, and why. A pre-mortem involves asking the group a few key questions:

- It's 5 years later and the project has been cancelled. What went wrong?

- It's 5 years later and the project is 50% over budget. What went wrong?

- It's 5 years later and the project has been nominated for awards for being delivered so successfully. What went right?

A pre-mortem is typically done with a white board or flip charts so that moment is not lost among the team members by trying to write each idea as a risk event and entering it into the risk register. Once the pre-mortem session is finished, the facilitator or notetaker can enter the risks into the register for the team to evaluate and assign likelihoods and impacts for each risk.

Assessing Risk Levels

The initial assessment of risk levels is to consider the risks with the current project execution plan and risk management practices in place. Assessing risks with the assumption that there are no risk practices in place can result in very conservative risk registers that create a sense that the project is not buildable. Alternatively, assuming that risks can be managed even though there is no formal risk management in place for the risk, creates an overly optimistic risk register that does not allow the project team to recognize where their risk management efforts should be focused.

It is important for the team to be honest about the effectiveness of current risk management practices so that current risks are defined as well as possible. This means not assuming that poorly implemented current practices are effectively managing risk and also not being overly pessimistic and assuming that none of the current practices will work.

Figure 7.1 Risk register with current risks.

The risk team should evaluate each risk and select a score for both the likelihood risk event will occur and the potential impact if the risk event occurs. This information can be documented in the risk register as shown in Figure 7.1.

Risks often have a range of outcomes that should all be assessed. Using the earlier example of a diesel spill during construction, this event could have a low likelihood/high impact, such as a major spill into a water body that the local community uses for drinking water. Or it might have a high likelihood/low impact, like a smaller spill contained on land that can be cleaned up easily. The particular event and consequence language that should be selected is the one with the highest risk severity (Likelihood x Impact). If the risk management approach is different for the two outcomes, then both possible risk events should be documented.

Although it is tempting to solve problems as soon as they are identified, it is important not to focus on managing risks when you are developing and assessing the initial list of current risks. If a good idea for risk management is identified during the discussion of the risk, then the facilitator should log the solution onto a “parking lot” and leave it for further, detailed discussion at the risk management stage. This avoids the project team spending valuable time on low-level risks, allowing them to identify all of the risks and then focus their attention on the high-impact risks during mitigation.

Risk Mapping

Once the likelihood and potential impact have been scored, the severity of the risk can be calculated (Severity = Likelihood x Impact), which can be helpful for ranking and sorting risks. The risk mapping can be done by placing risks into a risk severity diagram, as shown in Figure 7.2, and sorting the risks by severity for further analysis in the risk register. The risks can be color-coded to correspond to the level of risk. In this example, the risk level has been identified by the calculated severity:

Figure 7.2 Risk severity mapping.

- Extreme (Severity >14)

- High (Severity 7 to 14)

- Medium (Severity 3 to 6)

- Low (Severity <3)

It is important to note that neither likelihood nor impact are a linear scale but tend to be somewhat logarithmic, so a straight multiple can tend to underestimate the potential risk to the project, especially for extreme risks, and provides a conservative comparison of risks.

Risk Ranking

Once all the risk events have been scored, the register can be sorted to place the highest potential severity risks at the top of the register. This provides the team with a focus for the next stage of the risk management workshop, which is a discussion of options and plans. By sorting the risk register, the team can organize their time by spending much of their focus on the highest risks rather than on the lowest ones.

7.3 Risk Management Plans

Once the risk events have been ranked and prioritized, the project team should develop risk management plans to reduce the impact of the risk, the likelihood of the risk, or both. Managing or mitigating sustainability-related risks uses many of the same strategies as traditional project risk management.

Key project risks can be:

- Accepted – since you cannot eliminate all project risks, some risks need to be accepted as inherent in project delivery.

- Monitored – to evaluate if a risk is increasing or decreasing in impact or likelihood over time as the project develops.

- Controlled – to reduce potential impacts or likelihoods.

- Mitigated - by changing activities or designs to minimize or eliminate a risk.

- Transferred – to another party to reduce the project's risk.

Integrating sustainability into project delivery is a fundamental part of good risk management. Both the likelihood and the impact of many risks can be mitigated with strong community support. Communities are far less likely to protest, delay approvals, file lawsuits, or blockade construction sites if they believe that the company is operating with good intentions, is listening to concerns, and is working with the community to manage issues and concerns.

Environmental Risk Management

Managing environmental risks on a project can range from improving project design to reduce emissions to spill response during construction. Some environmental damage is unavoidable in developing major projects as most projects involve impacts like disturbing land and transporting materials to and from the project site. The goal of risk management is to understand which environmental risks could have an impact on the success of the project.

Monitoring environmental risks includes establishing an effective environmental management system (see Chapter 10) that provides the project team with metrics on the performance of the project. It also allows the team to respond to risk events and increase risk management procedures if there is an increase in the environmental events.

Environmental risks can be controlled by moving project facilities away from local communities to reduce noise or pollution concerns or by installing pollution control equipment to reduce emissions. Mitigating environmental risks might be achieved by changing activities or designs to completely eliminate impacts. This could be changing chemical processes to use nontoxic, green chemistry or by replacing diesel power generation with renewable energy to reduce emissions.

Environmental risks can also be transferred to another party to reduce the risk that the project is required to manage. This could include:

- Buying pollution liability insurance

- Transferring the responsibility for environmental management to contractors

- Purchasing new technology with performance contracts to reduce project risks for renewable energy or water treatment systems where suppliers have more expertise than the project team

Social Risk Management

Mitigating sustainability risks related to stakeholders and the local community can be more complex and challenging. There may not be technical solutions and you cannot buy insurance to protect against a loss of public support for the project. Managing social risks requires that the project team develop strategies and tools to establish clear communication, build trust, and support the local community.

Social risks can be accepted by the project team, but acceptance should not be the default option for social risks. The level of acceptance should be a strategic decision by the owner or project leadership that is based on the project charter and goals. Evaluation should encompass the level of social risk the project is prepared to accept, the level of impact it could have on the project schedule, the organization's reputation, and the long-term impact to operations that can be tolerated.

If the impacts of social risks are not well understood (especially in the project's early phases), then the best approach to risk management is to monitor the risks to see how the project messaging and the stakeholder engagement activities are being received by the local community, as discussed in Chapter 6. If the risk of a negative reaction from the community starts to increase, then the risk management approach can be elevated, and a more active approach can be taken.

A Sustainability Management System (see Chapter 8) can be used to manage social risks by ensuring that commitments made by the project team are understood and followed through by the project team. This can include developing a community agreement that clearly defines the potential impacts from the project and the benefits that the project will have for the community. It is difficult to transfer social risk away from the project and it is probably not a good idea to try. The project team can make sure that contractors and suppliers understand and share the risk by incorporating commitments and expectations for dealing with the local community into the procurement contracts (see Chapter 11).

Transferring social risk to another party through an insurance policy is not an option but you can think about a good sustainability management program as an insurance cost. How much would a project owner pay if they could buy insurance for events that damaged the project's community support? Would investors or financing firms require projects to have a “social insurance” policy if it was available? The answer is, of course they would. Building strong relationships and trust with the local community is the equivalent of buying insurance. It does not mean that there will be no damages from an event that impacts relationships with local communities, but that the damages will be lower. Similar to insurance policies that have deductibles, the sustainability program will not eliminate costs but can reduce the risk of large payouts and help to restore community support following an event. And like regular insurance that has a policy limit or aggregate limit of liability, the sustainability program does not provide endless protection against damages from poor performance or negligence.

Risk Management Action Plans

Risk is not managed simply by drafting a plan. Risks are managed by modifying activities, designs, behaviors, and processes in order to mitigate the risk. Each of the key mitigations will need to be documented, with a focus on:

- Who will “own” the mitigation?

- When will the mitigation be implemented?

- How often will status of the risk be monitored?

Figure 7.3 Risk register with planned risk management.

The risk management plans should be discussed during the risk workshop and documented in the risk register, as shown in Figure 7.3.

Evaluating Residual Risk

The next step in the process is to reassess the identified risks, assuming a reasonable and practical implementation of the proposed risk management measures. This step follows the same process that was used to evaluate the initial risk score. Each risk is reassessed for the likelihood and impact. Then the severity is calculated to establish whether the risk is low, medium, high, or extreme, as shown in Figure 7.4. If there are still risks identified as high or extreme following risk management, then the project team will need to look for new risk management options that can reduce these risks or ensure that the project team is focused on monitoring and controlling these risks.

Figure 7.4 Risk register with residual risk severity.

Risk management measures can rarely make risks go away entirely, so do not be overly optimistic about management plans. For example, you might indicate that a good environmental management plan will mitigate the risk of a major spill event. However, if your organization has only had limited success getting employees and contractors to follow environmental management plans in the past, then it cannot be assumed that your next environmental management plan will be any more successful and that spills will be eliminated.

7.4 Opportunity Management

Effectively managing risks is a fundamental part of good project management. It can reduce costs, avoid schedule delays, and allow projects to run more smoothly. But integrating sustainability into project management also requires identifying and implementing opportunities to reduce impacts, share economic benefits with local community, and deliver better projects.

Identifying opportunities can take place throughout the project delivery process but early identification of opportunities can ensure that the maximum benefit is achieved. Opportunities identified through the project sustainability strategy process (discussed in Chapter 4) can be used to pre-populate the opportunity register. Engaging with the local community (see the stakeholder engagement process in Chapter 6) may also provide ideas for project improvement, ideas influenced or drawn from traditional or indigenous knowledge, and intimate understandings of the local environment and landscape.

The opportunity register can be completed at the same time as the risk register. However, sometimes the focus on negative outcomes can put everyone in a mood of seeing primarily the project's pitfalls and less likely to find the opportunities. If the project is using a separate opportunity workshop, make sure that any ideas or opportunities to improve the project that are raised during the risk review process are captured and documented in the opportunity register.

Developing an opportunity register follows the same process as developing a risk register. The same tools that were used during the risk workshop can be used in an opportunity workshop. Conducting a pre-mortem can also be applied to identify opportunities. Consider these questions:

- The project was completed on time and under budget. What went well?

- We just won a major sustainability award for delivering the best project. What did we do to create success?

- The town council just gave the project director the keys to the city. How did we earn and maintain the community's support and respect?

Often, when assessing a particular project risk, the team will realize that mitigation might also create an opportunity for something positive from the project, in addition to reducing the risk. As an example, a risk that the local community could become angry with the project for not fulfilling promises to hire local people could be mitigated by job training programs to develop basic job skills in the local community. That risk mitigation could be taken a step further to create an opportunity to develop local skills by creating a local apprenticeship training program that would reduce project costs by developing highly skilled local employees that reduces construction costs and creates a skilled workforce for future operations.

Opportunities can also be identified early in the project lifecycle. During the design stage, engineering and architecture teams should be challenged to develop innovative solutions for reduced environmental impact, energy efficiency, and safe project delivery (discussed in Chapter 10). During procurement, bid documents and meetings should encourage contractors and suppliers to provide innovative options and solutions to improve logistics, reduce impacts, promote the local workforce, and leverage responsible supply chains (discussed in Chapter 11). All of these opportunities should be documented and tracked in an opportunity register.

Opportunity Impacts

The definitions used for risk likelihood can also be used for the likelihood of an opportunity being successful, but the definitions of impact need to be adjusted to reflect the positive impacts that could occur. Some examples of opportunity impact definitions are listed in Table 7.3. Note that your project team can develop their own definitions based on the specific project goals and objectives.

Opportunity Capture Plans

An Opportunity Capture Plan can be used to track and manage the potential opportunities in the same way that a Risk Management Plan is used. The plan should outline the process used to collect opportunities, define who will be responsible, and shape the schedule to investigate opportunities and execute selected opportunities. Investigation opportunities might involve the use of design workshops (potentially with the local community), options analysis and trade-off studies, and engagement with contractors and suppliers to see if potential opportunities are possible. Exploring and evaluating opportunities could also involve collaborating with research institutions, developing relationships with other projects in the local area, or developing innovation challenges to get input from project employees (see Chapter 10, “Design”).

Table 7.3 Example of opportunity impact definitions.

| Score | Impact | Financial Savings | Schedule Improvement | Environmental | Reputation/ Community Support |

| 5 | Huge | >$10 million | >6 months saved | Net-zero for energy and water use | Global awards |

| 4 | Major | $3–$10 million | 3 to 6 months saved | Carbon-neutral | Positive press |

| 3 | Moderate | $1–$3 million | 1 to 3 months saved | Green Chemistry Standards | Local recognition |

| 2 | Minor | $300k–$1 million | 1 week to 1 month saved | Reduced emissions or waste | Positive community Feedback |

| 1 | Insignificant | <300,000 | <1 week | Improved air quality | Positive employee feedback |

Figure 7.5 Opportunity register.

Opportunity Register

The opportunity register looks just like a risk register except that there is often no need to assess the impact of the opportunity under current management practices since opportunities tend to be new activities or new execution plans that don't have a current approach. An example of an opportunity register is shown in Figure 7.5.

Opportunity Mapping

Similar to risk mapping, opportunities can be ranked by calculating the potential for a positive outcome (Outcome = Likelihood x Impact) and mapping the opportunities in a table (see Figure 7.6), or by calculating the potential outcome and ranking the opportunities from high outcome to low outcome.

Figure 7.6 Opportunity mapping.

Once the outcomes have been mapped and ranked, the project team can focus on the opportunities with the highest potential outcome score and spend less time on opportunities that may have a lower potential outcome. This doesn't mean that the opportunities with a low outcome should be ignored, but they may not have a high enough payback to justify a full trade-off study or research project.

7.5 Summary

As we have discussed, integrating sustainability into a good risk management program doesn't require a lot of changes to the standard risk processes. What is required is to ensure that an effective risk management program is fully implemented and that steps are taken to ensure that sustainability risks are fully included and discussed. Steps include:

- Ensuring that knowledgeable people from various areas of sustainability are invited to the risk planning meetings and workshops

- Using structured tools like PESTLe analysis to explore a broad range of external risks

- Recognizing project goals related to community support and environmental impacts

- Scheduling meetings and workshops to ensure that there is time to discuss all risk topics, including sustainability topics

- Looking at opportunities not just to reduce risks, but to also create a better project

- Ensuring that there is effective follow-up on risk and opportunity management plans that include sustainability topics

Transitions between project phases or major changes in the project execution plan can introduce new risks or increase the severity of known risks. The risk and opportunity management strategies and plans will need to be updated as new risks are identified and as the project moves from design and procurement to construction and commissioning.

Sustainability risks are also changing rapidly. A project team may need to adapt quickly to changes in community and stakeholder expectations, increasing regulations, and evolving sustainability goals around climate change, water management, energy efficiency, and contributing to local employment.