Research Methodology

Research methodology refers to the strategies that researchers use to ensure that their work can be critiqued, repeated, and adapted. These strategies guide the choices researchers make with respect to sampling, data collection, and analysis. Thus there is and must be a close association and integration among research questions, research methodology, and methods of data collection. Research methodology is sometimes referred to as research design, or, as I said earlier, the blueprint or roadmap that guides a study. Here I use research methodology and research design interchangeably. Researchers, in developing their research methodology, must consider their assumptions; selection and perception biases; positionality (personal identity, status and influence relative to participants in the study, and the effect these might have on participants and data collection in general); and the rules they follow in research decision making (Traustadottir, 2001). An important consideration is the extent to which the researcher is from or is a long-term resident of the study community—that is, an insider, an outsider, or both (Brayboy & Deyhle, 2000; Fine, 1994b). Insider or outsider status and the way status is negotiated can exert some influence on the ways the researcher is perceived, what information can be collected, and how access to information may change over time as insider or outsider status is renegotiated.

All types of studies that are empirical require a design for research, regardless of which theories or approaches drive a given study. Methodology follows from the research questions and initial hypotheses. A discussion of methodology includes a consideration of the study setting or community and the study population—the people that are the focus of the study question and analysis. The researcher must also address sampling procedures and guidelines—what data are to be gathered and how, in relation to the study question, and how the data will be stored, managed, and analyzed. Dissemination of results may also be included in the study methodology. The case that follows provides an example of this methodological decision-making process.

CASE EXAMPLE

STUDY OF DEPRESSION IN OLDER LOW-INCOME ADULTS LIVING IN PUBLIC HOUSING DESIGNATED FOR PEOPLE OVER SIXTY-TWO

The Institute for Community Research and partners, including an area agency on aging and a network of public mental health clinics serving older adults, conducted a study of depression in a racially and ethnically diverse population of older adults living in senior housing in Connecticut (Diefenbach, Disch, Robison, Baez, & Coman, 2009; Disch, Schensul, Radda, & Robison, 2007; Robison et al., 2009; Schensul et al., 2006). The study addressed three main research questions:

- What were the lay understandings of the meaning of depression, and what language was used to describe feelings of loss and sadness, and the associated lack of functionality?

- What factors predicted clinical depression in the study population?

- What barriers to mental health treatment did this population encounter?

FIGURE 4.1 Formative Model of Research Areas

The outcomes were both scientific (publications in peer-reviewed journals) and directed toward local use of the data to advocate for improvements in mental health services for older low-income adults.

Based on their own community and service provision experience, and on the literature on depression in older, racially and ethnically diverse, low-income adults, the interdisciplinary research team members first identified some of the factors they believed to be associated with clinical depression. In this way they generated and drew a formative model that highlighted their greater knowledge of contributors to depression and their gaps in understanding barriers to treatment (see Figure 4.1, in which boxed sections represent areas of ethnographic research).

Selecting the Study Population

There were over twenty-four large buildings in the community that were home to low-income, racially and ethnically diverse, older adults. The study team could not conduct interviews in all of these buildings and thus needed a rationale for selecting approximately half of the buildings. To make the choice, the team eliminated some buildings that had atypical characteristics (for example, the residents all were working; many of the residents were younger with disabilities; the older adults lived in buildings that included many younger families; or the buildings were too small, with fewer than twenty-five residents). This left twelve buildings that were included in the final study building sample. The resident sample was a census (100 percent of the population) in each of the twelve buildings rather than another kind of sample, because the study included plans for network research to examine the relationships among each and every one of the residents in each of the buildings, and for this all residents had to be interviewed.

Identifying the Sample

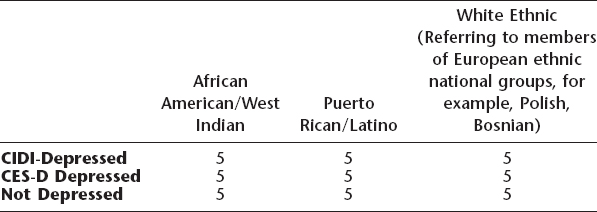

The study included two components: qualitative data (to understand the language and meanings associated with depression) and quantitative data (composed of a survey plus a survey-integrate network component that asked about each respondent's relationship with others in the building). The study team had to make a decision as to how many qualitative interviews to conduct. They decided that they needed interviews with an equal number of African American/West Indian and Puerto Rican/Latino males and females, divided into three groups: (1) those who scored as depressed on an established diagnostic tool for identifying clinical depression, the Composite International Diagnostic Instrument (CIDI); (2) those who did not score as depressed but described symptoms of depression on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), an instrument that screens for depression using a symptom checklist; and (3) those who had no signs of clinical depression or symptoms (see Table 4.1). To obtain five people in each of nine cells, forty-five in-depth interviews were required.

Data Collection

The study was funded for three years, thus requiring staging of data collection. This included piloting instruments: implementing a survey that included questions about barriers to care for those who were already diagnosed as depressed, as well as for those who qualified as depressed in the study. Qualitative data collection followed survey data collection and was based on the diagnostic categories in Table 4.1. Forty-five in-depth interviews focused on the areas in the outlined boxes in Figure 4.1—acculturation, history of and current life stresses, social networks and supports, descriptions of depression, sadness and loss, and barriers to care.

Table 4.1 Sampling Plan for In-Depth Interviews in a Depression Study

Data Analysis

The study team included experts in the analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data. Team members divided into two working groups, one to make decisions about how to code and analyze qualitative interview data and one to decide on the best analytic strategies for the survey and network data.

Dissemination of Results

Decisions concerning dissemination involved the identification of interested audiences and the preparation of results reports appropriate for each audience. Results were reported to study partners, to the state department of mental health, and to legislators concerned about the mental health of older adults. They were also used to support a building-based intervention to alleviate depression among building residents that was conducted by a partnering hospital with a geriatric mental health service.