Doing Grounded Theory Research

Several manuals provide different guidelines for conducting grounded theory research (see, for example, Charmaz, 2000, 2006; Clarke, 2005; Glaser, 1978, 1998; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990, 1998). Despite this variation, grounded theory researchers aim to conduct studies of individual and collective actions and of social and social psychological processes, such as experiencing identity transformations, changing organizational goals, and establishing public policies. Grounded theorists emphasize what people are doing and the meanings of their actions, such as their intentions; their own stated explanations; and their implicit, taken-for-granted assumptions (Charmaz, 2003, 2006). Nevertheless, even if we most often focus on actions and processes, we can also use grounded theory strategies to investigate other phenomena (for an example of generating a category system of school rules, see Thornberg, 2008a).

As constructivist grounded theorists, we view our methodological strategies as flexible guidelines to adopt as indicated through our involvement with data collection and analysis. Hence we see the constructivist approach to grounded theory methods as much less prescriptive and procedural than its earlier versions (Charmaz, 2006; Charmaz & Bryant, 2010). Furthermore, we do not narrow the method's focus to overt actions, visible processes, and explicit statements, because “the most important issues to study may be hidden, tacit, or elusive” (Charmaz, 2003, p. 91). Robert Thornberg's grounded theory study (2007) of inconsistencies in school rules demonstrates how a deeper analysis indicated that many of these everyday inconsistencies could be explained by studying how teachers applied implicit rules. Kathy Charmaz's study (1991) explicates how chronically ill people form and act on tacit meanings of time, and how these meanings foster changes in their self-concept.

Data Gathering in Grounded Theory

Grounded theory research uses data collection methods that best fit the research problem and enable the ongoing analysis of the data. This approach is therefore open to many methods of data collection. At the outset, a research problem may point to one method or a combination of methods for data gathering. If, for example, you want to study how and why disruptive behavior occurs in the classroom, you might begin to conduct classroom observations alone or in combination with informal conversations with the students and the teachers whom you observe. If you aim to explore experiences of management-staff conflicts in the workplace, you could conduct intensive interviews with people who have had such experiences. During the research process, your analysis of data evokes insights, hunches, “aha!” experiences, or questions and subsequent reflections, which might lead you to change your data collection method or add a new one. As long as you are conducting your study you have to think about how, where, and when to gather the data you need to address initial and emergent questions.

The first question you ask your data is, “What's happening here?” In line with this question, you might also ask the following: “What are the basic social processes? What are the basic social psychological processes? What are the participants' main concerns?” (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser, 1978). As you can see, you do not wait to construct the analysis until you have collected all the data for your study. Instead, you gather and analyze data simultaneously to raise and check your emerging questions and ideas (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser, 1978; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Furthermore, according to constructivist grounded theory, you and your participants construct data through your interpretive acts. Data are constructions of reality, not reality itself. For example, an ethnographer's conversation with a research participant reflects how each understands the other and their shared situation. The recorded field notes then reconstruct the conversation and situation but are renderings of the shared experience, not the experience itself.

Coding Data

Coding begins directly as the first data start to emerge in the study. Data collection and coding go hand in hand throughout the research project. Charmaz (2006) defines coding as “naming segments of data with a label that simultaneously categorizes, summarizes, and accounts for each piece of data” (p. 43). Grounded theorists create their codes by defining what the data are about. Glaser (1978) argues, “Coding gets the analyst off the empirical level by fracturing the data, then conceptually grouping it into codes that then become the theory which explains what is happening in the data” (p. 55). By coding, grounded theorists scrutinize and interact with their data, stopping and asking analytic questions of the collected data. This process may take them into unforeseen areas and new research questions. According to constructivist grounded theory, coding consists of at least two phases: initial coding and focused coding (Charmaz, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2008). Nevertheless, doing grounded theory is not a linear process. Sensitive grounded theorists move flexibly back and forth between the different phases of coding.

Initial Coding

When we conduct initial coding, which is also known as open coding, we stay close to the data and remain open to exploring what we define as going on in these data. Through the comparison of different segments of data, we also gradually begin to interpret and analyze (1) the main concern or concerns of the participants—that is, what they are focused on or view as problematic; (2) the tacit assumptions of the participants; (3) explicit processes and actions; and (4) latent processes and patterns. Glaser (1978, p. 57) states that during initial or open coding, the researcher asks a set of questions of the data:

- What is actually happening in the data?

- What are these data a study of?

- What category does this incident, statement, or segment of data indicate?

Charmaz (2006, pp. 47, 51) adds to these the following analytical questions, which may help during initial coding (see also Charmaz, 2003):

- What do the data suggest? Pronounce?

- From whose point of view?

- What do actions and statements in the data take for granted?

- What process(es) is at issue here? How can I define it?

- How does this process develop?

- Under which conditions does this process develop?

- How does the research participant(s) think, feel and act while involved in this process?

- When, why, and how does the process change?

- What are the consequences of the process?

We intend that a researcher use such questions as flexible ways of seeing, rather than applying them mechanically. Such questions help to search for and identify what is happening in the data and to look at the data critically and analytically. We conduct initial coding by reading and analyzing the data word by word, line by line, paragraph by paragraph, or incident by incident, and we may use more than one strategy. In her study of suffering, Charmaz (1999) engaged in both line-by-line coding of interviews with her research participants and incident-by-incident coding of interview stories about obtaining medical help during crises. By comparing incidents, she found unequal access to care within health organizations. Coding practices help us to see the familiar in a new light, avoid forcing data into preconceptions, and gain distance from our own as well as our participants' taken-for-granted assumptions (Charmaz, 2003; Glaser, 1978, 1998). During this careful reading we construct initial codes grounded in these data. Labeling codes with gerunds (noun forms of verbs), such as dissociating, controlling, and coping, helps us as grounded theorists to remain focused on action and process as well as to make connections between codes (Charmaz, 2006, 2008). In order to gain a good pace and to generate clear, understandable, and manageable initial codes, we keep the codes short, simple, precise, and active. We make sure that the codes fit the data instead of forcing the data to fit them. Each idea should earn its way into the analysis (Glaser, 1978).

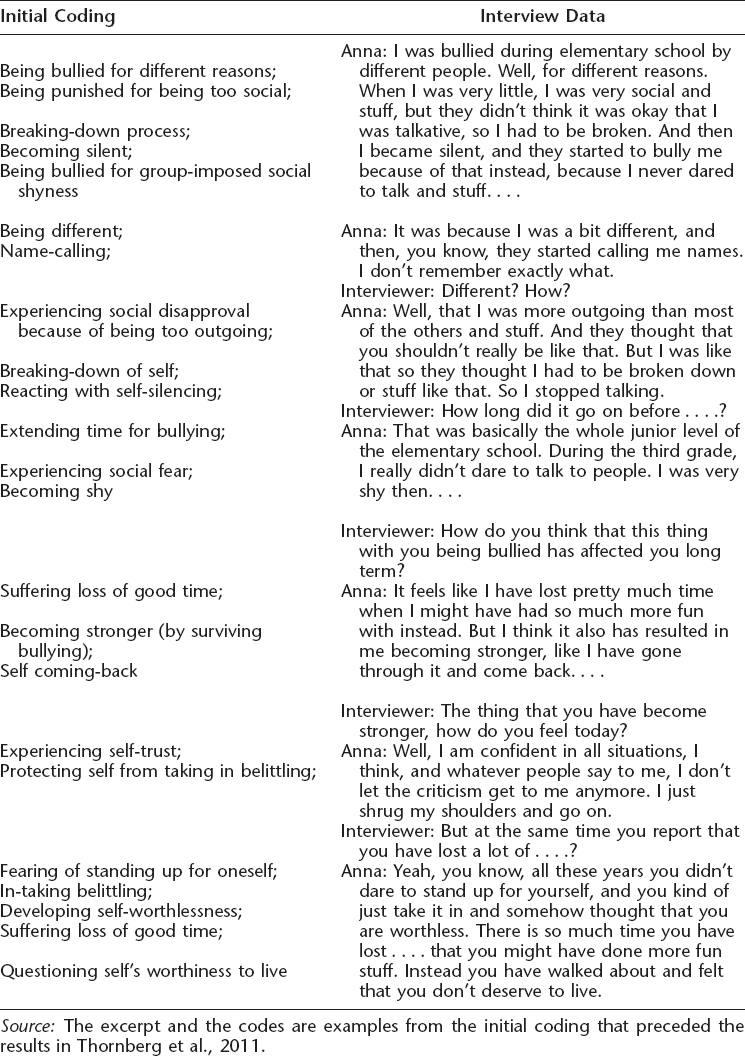

In the example in Table 3.1, Thornberg, Halldin, Petersson, and Bolmsjö (2011) conduct line-by-line initial coding. The four excerpts are taken from an interview with a fifteen-year-old female student who has experienced being bullied in school. Note that the codes are kept closely to data and are focused on action and process.

Initial coding often gives grounded theorists more than one direction to consider. We could, for example, use the excerpts in Table 3.1 to tentatively describe and further investigate (1) experiencing loss as a victim of school bullying; (2) the interplay between self-perception of being different and bullying victimization; or (3) the victim career trajectory by the phases of being devaluated by peers, developing self-worthiness, and self coming-back. Nevertheless, it is too premature to make such decisions yet, based on the limited set of data and initial codes in Table 3.1. More initial coding and constant comparisons have to be made in order to grasp a focus that is relevant to, works with, and fits the substantive field of study. Remember that initial codes are provisional and constantly open for modifications and refinements in order to improve their fit with the data. The constant comparative method expedites constructing a strong fit between data and codes. Because codes initially come very fast, recognize that these codes need to be constantly compared with new data. By using the constant comparative method, we compare data with data, data with codes, and codes with codes to find similarities and differences (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). These comparisons in turn might result in some sorting of initial codes into new, more elaborate codes.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- How would you define initial coding?

- What ideas does the example of initial coding in Table 3.1 give you about how researchers code their own data?

- How does initial coding challenge the researcher to think analytically?

Focused Coding

By conducting initial coding, the researcher will eventually “discover” the most significant or frequent initial codes. In focused coding, the researcher uses these codes to sift through large amounts of data (Charmaz, 2000, 2003, 2006). Glaser (1978, 1998, 2005) argues that you have to find and select one core category, the most significant or frequent code that also is related to as many other codes as possible and more codes than are other candidates for the core category. According to Glaser (1978), the core category “accounts for most of the variation in the pattern of behavior” (p. 93). This core category becomes a guide to further data gathering and coding (instead of focused coding, Glaser talks about selective coding, meaning that subsequent data gathering and coding are delimited to the core category and those codes or categories that relate to the core category; see also Glaser, 1998; Holton, 2007). The constructivist position of grounded theory is more flexible by being open for more than one significant or frequent initial code in order to conduct this further work. Such openness also means that the researcher continues to determine the adequacy of those codes during the focused coding (Charmaz, 2006).

Focused coding is more directed, selective, and conceptual than initial coding. By doing focused coding, we can begin to synthesize and explain larger segments of data. Grounded theorists are open-minded (in order to avoid preconceptions and to let unexpected ideas or insights emerge), sensitive, and active in the coding process. They return to study their earlier coded data to select focused codes among the initial codes or construct focused codes based on comparisons between clusters of initial codes. They also begin to code more data, guided by these more elaborated codes, but are still sensitive and open to modifying their codes and to being surprised by the data.

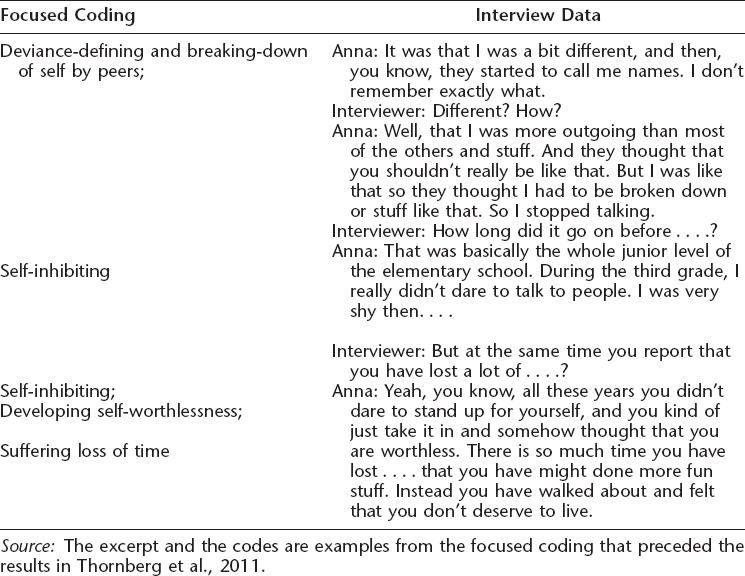

In the study of students whose peers bullied them, Thornberg et al. (2011) constructed the focused code “deviance-defining and breaking-down of self by peers” from constant comparison of many initial codes like “being punished for being too social,” “breaking-down process,” “being bullied for group-imposed social shyness,” “being different,” “experiencing social disapproval because of being too outgoing,” and “breaking-down of self” from the initial coding of the interview data in Table 3.1, as well as other initial codes generated by the earlier coding of other interview data, such as “being rejected because of not sharing the peers' interest in sport,” “putting-down process,” “being defined as deviant by peers,” “being constructed as a loner by peers and then punished for being a loner,” and “being socially rejected and dejected for not being cool enough.”

Thornberg et al. (2011) constructed the focused code “self-inhibiting” through the constant comparison of initial codes like “becoming silent,” “reacting with self-silencing,” “becoming shy,” “fearing of standing up for oneself,” and “inhibiting the social presence of self.” The focused code “developing self-worthlessness” was selected among the existing initial codes as it captures many other initial codes, like “questioning self's worthiness to live,” “initiating mistrust and bad thoughts of self,” “feelings of unworthiness,” and “beginning to devaluate oneself.” As can be seen in Table 3.2, in which parts of the interview data displayed in Table 3.1 have been recoded, the focused codes or categories were used to capture and synthesize the main themes in the interviewee's statements.

During focused coding, researchers explore codes and decide which best capture what they see happening in the data, and then raise these codes up to tentative conceptual categories for the grounded theory they are going to construct. The researchers give the categories conceptual definitions and assess the relationships between them. For example, the focused code “deviance-defining and breaking-down of self by peers” in Table 3.2 was later conceptualized as the category “stigma cycling,” which refers to a cycling process between the following two subprocesses: peers (1) devaluing a student by defining and labeling him or her as different, odd, or deviant, and (2) breaking down the student's self by repeatedly harassing and rejecting him or her. As long as the stigma cycling takes place, peers severely attack the victim's identity and self-value. This basic social process forces the victim to develop a negative-loaded deviant identity and a general expectation of being unwanted, rejected, and harassed by others—and to connect these two things. Nevertheless, further analysis also indicated a turning point among some of the victims, which broke the stigma cycling and initiated a coming-back trajectory. The names and definitions of the generated categories should be treated as approximate and provisional, and thus open for further development and revision during the entire analysis process.

In order to generate and refine categories, grounded theorists have to compare data, incidents, and codes, and then later compare their categories with other categories. According to Charmaz (2003, p. 101), making the following comparisons might be helpful during focused coding:

- Comparing different people (in regard to their beliefs, situations, actions, accounts, or experiences)

- Comparing data from the same individuals at different points in time

- Comparing specific data with the criteria for the category

- Comparing categories in the analysis with other categories

In addition, we suggest that the following comparisons are also useful during focused coding:

- Comparing and grouping codes, and comparing codes with emerging categories

- Comparing different incidents (for example, social situations, actions, social processes, or interaction patterns)

- Comparing data from the same or similar phenomenon, action, or process in different situations and contexts

In an ongoing study of school consultation and multi-professional collaboration between teachers and nonschool consultants concerning hard-to-teach students, Thornberg (2011) raised a focused code, “professional collision,” to a category and tentatively defined it as collision between different professional perspectives, goals, and practices. By comparing this category with data and focused codes, he constructed other focused codes as categories, such as “remaining outsiders” and “resisting change of the school culture.” By comparing these and other categories with each other, and with data and focused codes, Thornberg began to develop a grounded theory of consultation barriers between teachers and nonschool consultants.

According to this grounded theory, consultation barriers were constructed and maintained by social processes like professional collision; resisting change of the school culture, manifested in teachers' attitudes and actions; and nonschool consultants' remaining outsiders (professional marginalizing in the school context and failing to receive acceptance and legitimacy from teachers). The barriers served and protected each professional group's identity, self-serving social representations, and latent patterns. This complex social process of consultation barriers might be called, in Glaser's terminology (1978, 1998, 2005) the core category of the study. Thornberg linked the process of enacting professional and cultural barriers to most other categories and focused codes—including categories that indicated properties and dimensions of the process, such as professional collision, remaining outsiders, and resisting change of the school culture, as well as categories that indicated consequences of the process, such as consultation disengagement and consultation loss.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- What is focused coding? When would researchers use it?

- In which ways does Thornberg et al.'s focused coding (2011) of the data on bullying advance their analysis?

- What challenges should researchers foresee when doing focused coding?

Theoretical Coding

In addition to conducting initial and focused coding, grounded theorists might also take advantage of what Glaser (1978, 1998, 2005) calls theoretical coding. Glaser (1978) introduces theoretical codes as tools for conceptualizing how categories and codes generated from data may relate to each other as hypotheses to be integrated into a theory. Theoretical codes “give integrative scope, broad pictures and a new perspective” (Glaser, 1978, p. 72). They “specify possible relationships between categories you have developed in your focused coding…[and] may help you tell an analytic story that has coherence” (Charmaz, 2006, p. 63). Holton (2007) defines theoretical coding as “the identification and use of appropriate theoretical codes to achieve an integrated theoretical framework for the overall grounded theory” (p. 283).

By studying many theories, grounded theorists may identify numerous integrating logics (that is, theoretical codes) embedded in these theories, and hence develop a repertoire or knowledge bank of theoretical codes (Glaser, 1998, 2005).

One reads theories in any field and tries to figure out the theoretical models being used.… It is a challenge to penetrate the patterns of latent logic in other's [sic] writings. It makes the researcher sensitive to many codes and how they are used. He or she should take the time it takes to understand as many theoretical codes as possible by reading the research literature. This is a very important part of developing theoretical sensitivity. (Glaser, 1998, pp. 164–165)

Glaser (2005) argues that the more theoretical codes the grounded theorists learn, the more they have “the variability of seeing them emerge and fitting them to the theory” (p. 11). Glaser (1978) presented as a guide a list of theoretical codes organized in a typology of coding families, and made later additions to this list (Glaser, 1998, 2005). In Table 3.3 we have listed some of Glaser's coding families.

Glaser's list (1978, 1998, 2005) contains many more coding families. Nevertheless, Glaser's list is by no means exhaustive, and coding families reveal considerable overlapping. In addition, Charmaz (2006) points out that several coding families are absent from Glaser's list, and other coding families appear rather arbitrary and vague. Instead of being hypnotized by his list, researchers should investigate all kinds of theories they encounter in education and the social sciences, as well as in other professional domains, in order to figure out for themselves their embedded theoretical codes. Subsequently they will view theoretical codes as analytic tools that, if relevant, they may draw on. If, for example, researchers discern a significant process in their data and emerging analysis, then they could draw on the concepts in Glaser's Process coding family (see Table 3.3) that fit the data (for example, phases, passages, careers, and so on).

Table 3.3 Examples of Glaser's Coding Families

| Coding Families | Theoretical Codes |

| Source: Adapted from Glaser, 1978, 1998. | |

| The “Six C's” | Causes, Contexts, Contingencies, Consequences, Covariances, and Conditions |

| Process | Phases, progressions, passages, transitions, careers, trajectories, cycling, and so on |

| Degree Family | Limit, range, grades, continuum, level, and so on |

| Dimension Family | Dimensions, sector, segment, part, aspect, section, and so on |

| Type Family | Type, kinds, styles, classes, genre, and so on |

| Identity-Self Family | Self-image, self-concept, self-worth, self-evaluation, identity, transformations of self, and so on |

| Cultural Family | Social norms, social values, social beliefs, and so on |

| Paired Opposite Family | Ingroup-outgroup, in-out, manifest-latent, explicit-implicit, overt-covert, informal-formal, and so on |

However, the risk arises that grounded theorists might force theoretical codes into their analyses. Glaser (1978) strongly argues that theoretical codes have to earn their way into the grounded theory by constant comparison. They must work, have relevance, and fit with data, codes, and categories. Usually grounded theorists more or less consciously or unconsciously use a combination of theoretical codes in order to relate, organize, and integrate their categories into a grounded theory. By possessing a broad repertoire of theoretical codes, researchers can view their data and categories from as many different relevant theoretical perspectives as they can envision in order to explore and evaluate the usefulness of a lot of theoretical codes for relating, organizing, and integrating the categories and codes into a grounded theory.

In Thornberg's study (2010a) of how schoolchildren explain bullying, he combined different theoretical codes to develop a typology of children's social representations of causes of bullying: bullying as a reaction to deviance, bullying as social positioning, bullying as the work of a disturbed bully, bullying as a revengeful action, bullying as an amusing game, bullying as social contamination, and bullying as a thoughtless happening. By constructing a typology grounded in data and in codes and categories generated in the analysis, Thornberg actually established connections between categories in accordance with Glaser's Type Family (1978) included in Table 3.3, which fit very well with the data and the categories. He also used “social representation,” which can be linked to the Cultural Family in terms of social beliefs, as a sensitizing concept. Blumer (1969) used the term sensitizing concepts to refer to general concepts that do not claim to be the truth but merely suggest a direction in which to look and to make possible interpretations. As Charmaz (2006) puts it, “These concepts give you initial ideas to pursue and sensitize you to ask particular kinds of questions about your topic” (p. 16). They give a loose frame to the empirical interest without forcing this frame on the data.

By comparing data, codes, categories, and memos (see the next section) with different theoretical codes, Thornberg (2010a) was able to see different possibilities of organizing and relating his categories in ways that reflected his data and the content of his categories. In addition, by doing a careful reading, grounded theorists might also detect many theoretical codes, such as normality-deviance, social norms, strategies, positioning, social control, power, and social influence, embedded in the children's social representations of bullying causes.

Even if theoretical coding has great potential to empower grounded theory research, Charmaz (2006) highlights some cautions that should be considered when conducting coding:

These theoretical codes may lend an aura of objectivity to an analysis, but the codes themselves do not stand as some objective criteria about which scholars would agree or that they could uncritically apply. When your analysis indicates, use theoretical codes to help you clarify and sharpen your analysis but avoid imposing a forced framework on it with them. (p. 66)

Remember that the categories can be related to each other in many different ways depending on the grounded theorists' knowledge and meaning-makings of theoretical codes as well as on their preferences and perspectives as researchers. Grounded theories do not already exist out there in reality to be found but are always constructed by researchers through their interactions with and interpretations of the field and participants under study.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- What are theoretical codes?

- Why should researchers be cautious about using theoretical codes?

- What challenges might using theoretical codes impose?