Practitioner Research Designs

Practitioners will find it useful to follow some kind of guidelines for designing practical studies of their own work, and one such model (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1982) has been adapted and applied in our cases of Mr. Crane and Ms. Drake. To review, these stages are focusing, planning, acting, observing, reflecting, and revising (followed by refocusing). Using our two practitioner researchers as examples following this model, we see Mr. Crane and Ms. Drake conducting their research in each stage in Exhibit 12.1.

SCENARIO EXAMPLES OF THE PRACTITIONER RESEARCH STAGES

- Mr. Crane finds his students reluctant to talk in class.

- Ms. Drake suspects she is obtaining only partial client reports in initial interviews.

Planning

- Mr. Crane thinks about using silence and more open-ended questions.

- Ms. Drake decides on applying a clarification strategy.

Acting

- Mr. Crane teaches using silence and open-ended questions, taping the experiment.

- Ms. Drake interviews a client using the clarifying statement technique, taping the experiment and implementing a questionnaire.

Observing

- Mr. Crane listens to the tape for examples of silence and questions.

- Ms. Drake listens to the tape and reads the completed questionnaire to gauge the effect of the clarifying statement experiment.

Reflecting

- Mr. Crane decides questions work but silence does not.

- Ms. Drake finds her restatements sometimes useful, sometimes parroting.

Revising

- Mr. Crane revises his questions and cancels the silence idea.

- Ms. Drake develops better clarifying statements and eliminates parroting examples.

Refocusing

- Mr. Crane has a new plan for increasing student verbal involvement.

- Ms. Drake has a new plan for encouraging client reporting.

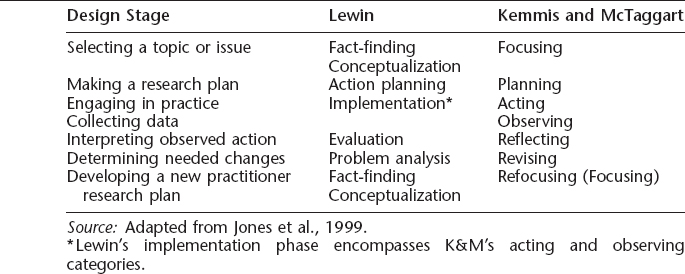

Table 12.1 Comparison of the Lewin (1948) and Kemmis and McTaggart (1982) Research Models

Kemmis and McTaggart (K&M) developed their design steps for practitioner research based on the work of Lewin (1948), who, as explained, originated the practitioner action research idea decades earlier. In Lewin's format, he outlines his stages as fact-finding, conceptualization, action planning, implementation, evaluation, and problem analysis. The elements of this structure are comparable to the K&M framework, as shown in Table 12.1.

There are two rather subtle but important differences between the Lewin and K&M designs that deserve attention. First, Lewin does not directly address the role of observation, incorporating it as part of his implementation category. And, although K&M consider refocusing an essential activity to emphasize the spiraled cycle pattern noted earlier, Lewin's model implies beginning once again with fact-finding and conceptualization. To be fair, though, Lewin made clear in his writing that a spiraled cycle of growth was a crucial aim of his recommended practitioner research sequence.

Most who write about practitioner research follow design sequences quite similar to those offered by Lewin and K&M, although some (Johnson, 1995, for example) have departed from this pattern by designating the initial stage as problem identification. This conception of beginning by locating difficulties may lead to a deficit orientation, implying that practitioner research should be conducted only when professionals experience trouble or serious problems in their work. However, as Schön (1983) has explained, professionals who frequently and effectively engage in move-testing (a form of practitioner research) are also those found to be superior performers in their practice. Practitioner research should not be just for teachers who have severe discipline problems or lawyers who too often improperly represent their clients.