Chapter 13

Staffing

Introduction

No matter how well designed a system may be, it can only be as good as the people who run it. As we have seen, competent, well-motivated staff are an essential element of any successful service operation. This is a matter of selecting the right people, giving them the right equipment, inducting and training them properly, then letting them get on with it, using the control process we have already described to monitor their performance.

These activities overlap into other management subjects. Staffing, for instance, covers the establishment of appropriate staffing levels, recruitment, selection, induction, training, motivation, welfare and appraisal. Most of these are the province of the human relations expert, and we do not intend to do more than cover them in outline here, just in case you find yourself working for the smaller kind of organization. Even then, you are advised to consult a good human relations textbook.

What we do propose to look at more fully are the questions most likely to be asked of the rooms division manager, namely:

![]() How many staff are required?

How many staff are required?

![]() What kind of recruits are needed?

What kind of recruits are needed?

![]() What special training requirements do they have?

What special training requirements do they have?

This should allow us to prepare a specimen job description and a specimen human resource management specification (the latter as a basis for interviews), which is something that the human resource management department would ask the front office manager to do in a large hotel.

Front office organization

We have already looked at the place of front office within the hotel as a whole. All we need to remind you of here is that it has six main responsibilities, namely:

![]() Advance bookings

Advance bookings

![]() Switchboard

Switchboard

![]() Reception

Reception

![]() Billing

Billing

![]() Cashier

Cashier

![]() Uniformed staff/Concierge

Uniformed staff/Concierge

In a large hotel, these may all be separate sections, each with its own supervisor, as shown in Figure 61.

In small establishments, all the duties may have to be undertaken by a single receptionist, who may find herself taking bookings, registering arrivals, putting calls through, posting charges and taking payments at different times (occasionally all at once, or so it can seem!).

In addition, management staff must be available to deal with major problems or the kind of guest who says, ‘I demand to see the manager’. In a small hotel these responsibilities will be undertaken by the manager or assistant manager. In a large hotel there may well be a number of ‘duty managers’, who cover a twenty-four-hour period between them and whose job it is to make sure that the various section supervisors cooperate in solving any problems which arise.

Even in large hotels, it is a good policy to move front office staff around so that they can experience different aspects of the job. This helps to maintain their interest and enthusiasm, increases staff flexibility and improves their promotion prospects. Some such hotels start new staff in the back office so that they can learn about the rooms and the systems in operation before going onto reception to meet real live customers on a face-to-face basis. All-round experience is also valuable because the work often comes in peaks and troughs, and it is useful to be able to pull somebody out of the back office, say, and put them on the desk to help deal with a sudden rush of arrivals.

Figure 61 Front office organization chart

‘Job enlargement’ has been advocated by many organization theorists, and some attempts have been made to apply this on a more extended scale. One major company experimented with appointments inspired by the concept of the ‘air hostess’. These employees were expected to handle not only reception duties but also housekeeping and food and beverage service, with the emphasis placed very much on customer relations. However, the range of duties involved was too wide, and the experiment was not a success.

Other attempts have been made to apply the concept within front office. The idea is to encourage a single receptionist to deal with a particular guest or group of guests throughout their stay as far as possible. Shift patterns make this difficult to achieve, but it certainly develops a feeling of involvement on both sides, and helps to counteract the feeling of anonymity that guests sometimes get in very large and busy establishments.

The ‘host’ or ‘hostess’ concept has also been tried occasionally. Guests are greeted by a pleasant, attractive, well-groomed person who directs them to the appropriate clerk and makes sure that the clerical functions are handled smoothly. However, there is an element of artificiality about trying to separate the ‘hospitality’ side of the job from the ‘clerical’, and our view is that all front office staff should employ social skills as an integral part of their job.

Numbers and hours

How many receptionists are needed? This is very difficult to say. An old rule of thumb was that a receptionist ought to be able to handle 50-60 occupied rooms. However, this formula excluded switchboard operators and back office staff. If the receptionist was also required to handle guest billing and cashiering duties, the ratio would have to be substantially reduced. All we can usefully say is that it depends on:

1 The occupancy rate. Empty rooms do not give rise to any clerical activities or customer contact.

2 The average length of stay. Guests who stay for seven nights on inclusive terms put less of a burden on front office than one-night stays (they only need to be registered once, and their bills are simpler).

3 The pattern of activity. Most hotels experience departure and arrival ‘peaks’ in the early morning and the later afternoon, and these may call for extra staff to be on duty. Resort hotels may have similar weekend ‘peaks’. On the other hand, a busy airport hotel may have a much more even distribution of arrivals and departures.

4 The amount of personal contact required. This can be reduced by various means. Groups can be preregistered, or some of the formalities can be looked after by the group organizers. Automated check-in and check-out can reduce the amount of time the guest needs to spend at reception. Experienced ‘FITs’ (frequent independent travellers) may welcome such innovations, but other guests still prefer the personal touch, and contact times should allow for the pleasantries which help to create that impression of ‘hospitality’.

5 The character of the hotel. A few minutes’ wait might be acceptable in a small country hotel catering for a leisure market, whereas it is quite inappropriate in a busy city centre environment. Luxury hotels in particular must try to avoid exposing their guests to the indignity of having to queue, even for a few minutes.

6 The technology being employed. Manual methods are more expensive in terms of clerical time than mechanized or computerized ones. Automated telephone exchanges reduce the number of telephonists required, for instance, and point of sale terminals can considerably reduce the amount of voucher posting that has to be done.

The best way to approach the question of staffing requirements is to consider what has to be done, and when it must be done by. This should be determined by the guest's needs, not the hotel's. The guest wants to be checked in smoothly on arrival, shown to a clean, vacant room, allowed to eat, drink and enjoy an undisturbed night's sleep, and then checked out again swiftly and efficiently when he leaves, and it is up to the hotel to arrange its staff schedules to make sure that this happens. Let us consider the activity patterns of the main front office areas:

1 Advance booking requests for a large international hotel may come in at any time of the day or night, but in most establishments they will tend to be concentrated during normal business hours, with something of a ‘peak’ when the morning mail arrives.

2 The switchboard will also be busiest during normal business hours.

3 The desk will have to be staffed from the early morning to the late evening, and large, busy hotels will need somebody on duty overnight as well. The main ‘peaks’ will come when guests depart (usually 7.30 to 10.30 a.m.) and arrive (about 3.00 to 7.00 p.m.).

4 The billing and cashiering ‘peaks’ will be concentrated in the morning (when early morning teas, breakfasts, etc. have to be posted), the middle of the day (lunchtime postings and dealing with bar and restaurant takings), and the evening (opening bills for new arrivals, posting accommodation charges and bar and restaurant vouchers).

5 The control process should go on all the time, but the natural time for a general review of the day's activities is the middle of the night, when most guests are asleep and there is time to check the figures before they wake up and start demanding their bills. This is so common that the process is almost universally known as ‘night audit’.

What this activity pattern calls for is a series of shifts. With a normal working day of eight hours, the whole twenty-four-hour period can be covered by three consecutive shifts, namely:

![]() An ‘early’ shift starting some time between 06.30 and 07.30

An ‘early’ shift starting some time between 06.30 and 07.30

![]() A ‘late’ shift starting between 14.30 and 15.30

A ‘late’ shift starting between 14.30 and 15.30

![]() A ‘night’ (or ‘graveyard’) shift from 22.30-23.30 to 06.30-07.30 again.

A ‘night’ (or ‘graveyard’) shift from 22.30-23.30 to 06.30-07.30 again.

The night shift does not usually require so many staff as the other two, and often attracts specialists who for some reason or other don't mind working at night.

This shift pattern undoubtedly creates problems. Staff have to start or finish earlier or later than in most jobs. There are sometimes transportation difficulties, and the personal security of staff (especially female ones) going home late at night is a legitimate cause for concern. Weekend work is also necessary because hotels have to remain open seven days a week, but it is not always popular.

Some of the stress can be reduced by introducing a supplementary ‘middle’ shift, which might last from mid-morning to early evening (08.30-10.30 to 16.30-18.30). This covers the normal business hours and many of the back office activities, like taking advance bookings. It might suit an older, experienced person with a family, or could be introduced as part of a rota scheme to allow staff a ‘normal’ day at regular intervals.

Arranging staff rotas is one of the most challenging of the front office manager's duties. The front desk must be covered at all times (except in small hotels), on weekends as well as weekdays. Holiday entitlements need to be built in, and rotas arranged in advance so that staff know when they are going to be off duty, even though the hotel may have to cope with considerable variations in terms of occupancy. The rotas must be seen to be fair to all concerned, but there must be a judicious mixture of youth and experience on duty at any time. The need to draw up staff rotas (in the housekeeping and food and beverage departments as well as front office) is one of the main reasons for producing medium-range occupancy forecasts.

Assuming a medium-sized hotel operating a standard three-shift pattern, the day's work might be programmed as follows (this is a simplified example: most hotels will have their own terms relating to the specific equipment and procedures being used):

| 07.00-09.00 | Early shift take over from night shift. Check float; early morning calls, post early morning teas, papers, etc.; check out departures; present bills; deal with payments; file registration cards. |

| 09.00-12.00 | Mail (advance bookings and confirmations, etc.); check stopovers on chart and liaise with housekeeper; check stopovers for credit limits; check room availability and ring round other hotels if necessary; check housekeeper's report and account for discrepancies (if any); run key check if appropriate. |

| 12.00 on | Post lunches to bills, cash up lunch and bar receipts. |

| 15.00 | Check float and safe, reconcile cash, etc. |

| 15.00-17.00 | Late shift takes over. Check float, etc.; check room availability and current arrivals list; check any VIP arrivals and confirm arrangements; prepare arrivals and departures lists for next day; prepare registration cards for next day; file correspondence; check in early arrivals. |

| 17.00-20.00 | Check in normal arrivals; check 6 p.m. releases and ensure these rooms available for chance requests; check any no shows; deal with book-outs (if necessary). |

| 20.00-23.00 | Post room charges, dinner and bar vouchers; check float and safe, reconcile cash, etc. |

| 23.00-07.00 | Night shift takes over; check float, etc.; check in late arrivals and chance guests; check room status report; carry out night audit; run back-up procedures. |

Staff selection

One of the rooms division manager's tasks is to recruit new front office staff. In a new hotel, she must start from scratch and select a complete team. This will generally be built around one or two key employees with previous experience, but many of the recruits will be new to the job, and they will certainly be new to each other. In an established hotel, it will generally be a question of filling individual vacancies. Labour turnover among receptionists varies from hotel to hotel, but some changes are inevitable.

The aim of the recruitment process is to select the best person for the job. This means that the person doing the recruiting must have a clear idea of what the job entails. The best method of ensuring this is to prepare a detailed job description. These will vary in detail from hotel to hotel, according to the systems, procedures and equipment used, but will bear a general resemblance to the example shown in Figure 62.

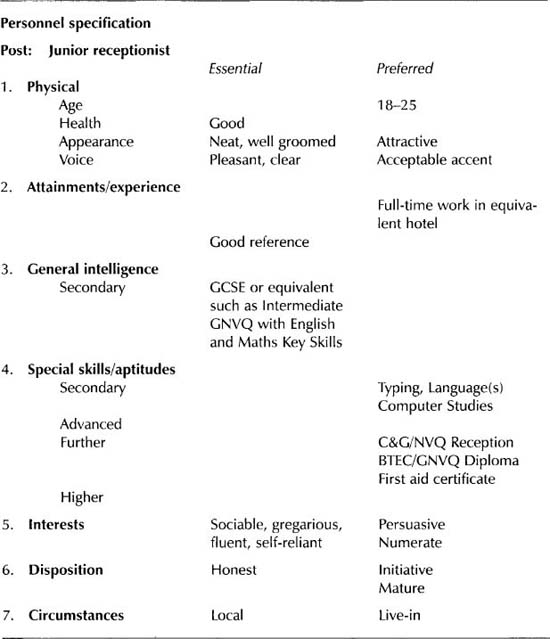

It is also desirable to have an idea of what kind of person you are looking for to fill the vacancy in question. The recommended method of achieving this is to prepare a personnel specification. This ought to cover the main points against which you will be assessing applicants. There is no need to work these out for yourself: human resource management experts have already produced well-tried interview plans, and it makes sense to follow one of these in preparing your personnel specification, since this allows you to conduct an effective and comprehensive interview.

The National Institute of Industrial Psychology's well-known ‘seven-point interview plan’ allows us to consider the following points:

1 Physical requirements

The job has few taxing physical requirements, except that receptionists do rather more standing than is usual in clerical jobs (though this is less true of back office personnel or telephonists). However, the hours do impose a certain amount of stress, which is why many rooms division managers have a preference for younger applicants, who can be expected to be more resilient.

Physical appearance is an important factor, since the receptionist is one of the chief representatives of the hotel as far as the guest is concerned. Other things being equal, a rooms division manager would prefer a reasonably good looking applicant to one who was physically unattractive. However, the standards are not impossibly high: you do not have to look like a film star to get a job in front office. Attention paid to grooming is far more important: neat hair, a clean face and hands, and tidy clothes will normally be sufficient for most situations, especially if they are accompanied by a pleasant smile.

2 Attainments

An applicant's previous experience can be a valuable guide to her likely effectiveness. Obviously, previous front office experience is the best recommendation, though this needs to be tempered with common sense: what is right for one hotel is not necessarily right for another, and you don't want to recruit the kind of person who is always saying, ‘That's not the way we used to do it at the Superbe’.

If this is not available, then clerical experience of some other kind is useful, especially if it involved dealing with the public in a customer service context. Such applicants will be prepared to meet the occasional rude or even hostile guest, and should have evolved their own strategies for dealing with them. This aspect of the job needs to be made clear to all the applicants, so that if they aren't willing to be civil they can withdraw their application before it is too late.

Records of previous employment can be read with an eye to spotting significant unexplained ‘gaps’ or unusually rapid job turnover patterns. Front office staff are often in a position of trust as far as guests’ valuables are concerned, so honesty is an essential quality. They will have to relieve their colleagues at awkward times, so reliability is another important quality. Someone who has never worked early or late hours, or in a situation calling for the display of individual initiative, is an unknown quantity as far as front office is concerned.

3 General intelligence

The clerical aspects of the job call for staff who are reasonably literate and numerate. Clerical entry requirements are usually expressed in terms of school leaving qualifications: there is no such thing as a rigid requirement, but a commonly accepted standard includes school leaving level passes in English and mathematics.

4 Special skills and aptitudes

Obviously, a qualification in reception work is a very considerable recommendation, since the applicant has already demonstrated both interest and aptitude, and will consequently require less training. You should be aware of the range of such certificates, including the National Vocational Qualifications and their Scottish equivalents (NVQs and SVQs) developed by the Hotel and Catering Training Company. The first level confirms the holder's competence at relatively simple tasks such as dealing with telephone calls, providing customer information and handling and transporting customer property, while the higher levels demonstrate the holder's competence in managing operations, resources, people, the environment and information.

Other than this, the special skills called for fall into three main groups:

– Keyboard (i.e. typing, machine operating or computer) skills. These are highly desirable in most front office situations. There are still many small establishments which use manual tabular ledgers and produce hand-written bills, but hardly any which would dream of sending out a hand-written letter. Keyboard skills of some kind are thus essential, and familiarity with the layout of a typewriter keyboard can easily be transferred to a computer. A knowledge of computer programming or how a computer actually works is not necessary: far more important is the ability to follow manuals which are still, alas, not particularly ‘user friendly’.

– Linguistic skills. A knowledge of one or more of the foreign languages likely to be used by guests is a valuable asset, especially if it covers what the language specialists call ‘oral/aural’ skills (i.e. the ability to understand what people are saying to you, and to respond effectively).

– Intercultural skills. This means an awareness of the existence of intercultural differences and the ability to deal with them. It tends to come with a knowledge of languages, but it can also be the product of foreign travel, so it is worth looking for evidence of that on an application form.

5 Interests

This heading is mainly of use because it provides some clues as to the applicant's personality traits, which are discussed next.

6 Disposition

This is perhaps the most difficult area to assess, and also the hardest to sum up in words. Nevertheless, it is very important. We all know that our friends tend to behave in fairly predictable ways: ‘X’ is always cheerful and enthusiastic, for instance, whereas ‘Y’ can be grumpy and irritable, and ‘Z’ is often timid and lacking in initiative. There is a good deal of argument regarding the extent to which these characteristics are innate or acquired: for our purposes this is less important than the fact that people do exhibit differences of personality. Let us consider what personality traits are required by front office staff. As we have seen, the job has three main elements:

– Clerical. This requires staff to be conscientious, methodical and accurate. Because they may have to be on duty alone, they also need to be self-reliant, and since the problems are often ‘immediate’ ones, they must be prepared to accept responsibility.

– ‘Hospitality’. This requires staff to be friendly, sympathetic and understanding, and to possess the behavioural skills necessary to project these qualities. We have discussed these skills in some detail earlier: to some extent they can be acquired, but it is still true that some people possess them naturally to a greater extent than others.

– Selling. This requires staff to be knowledgeable, enthusiastic and persuasive. In these days of yield management, it also requires them to be reasonably numerate, and tough enough to be able to negotiate successfully with people like tour organizers who make a living out of driving hard bargains.

To some extent these qualities are mutually exclusive. It is not easy to be tough when you are naturally sympathetic, or to sound understanding when your feet hurt and there are several reports and reconciliations to be completed before you can hand over.

The real clash of attributes is between the ‘introvert’ and the ‘extrovert’. Introverts are naturally self-absorbed, shy and withdrawn. They are not easily distracted and are generally careful and methodical: necessary qualities, in fact, for the ‘clerical’ side of the task. Extroverts, by contrast, are naturally gregarious and spontaneous, but they are more easily distracted and not always as careful as they should be.

The question is, which set of qualities should you put first? Ideally you want a combination of both, but it is not always possible to find this. The choice is influenced by three considerations:

– The procedures are not hard to master, whereas it is much more difficult to teach social skills.

– An effective control process should ‘catch’ any serious procedural errors.

– The effect of any such errors can usually be cancelled out by the prompt exercise of social skills.

These suggest that if it is necessary to choose, it would be better to go for the applicant who is naturally hospitable.

The extent to which applicants possess these traits can be assessed both before and during interview. The completed application form often offers indications as to the presence or otherwise of desirable qualities. Examination successes not only indicate the possession of specific skills and a certain level of general intelligence, but also (by implication) a methodical approach and a degree of self-motivation. Many forms contain an ‘interests’ section, and this can tell you much about an applicant. Indications of sociability are valuable (club membership, for instance), as is any evidence of organizing ability or a constructive concern for other people (someone who shows such concern in their private life is likely to project it in their professional guise, too).

The interview has many limitations as a selection method, but it does enable you to assess the applicant's social skills directly. An applicant who turns up untidily dressed, who mumbles her answers and who fails to respond to your welcoming smile is hardly likely to behave very differently when she is behind the reception desk, and should not be selected. Interviewees who recognize the importance of being well turned out and who can be fluent and outgoing in what is admittedly a stressful situation are likely to exhibit the same qualities in employment. However, allowances have to be made for differences in background: a school leaver attending her first interview is unlikely to be as confident as someone with several years’ experience.

7 Circumstances

This is of some importance because of the special requirements of the job. Applicants who are restricted to regular business hours for some reason or other (husbands, wives, children, etc.), or who would have to travel long distances at inconvenient times, are clearly at a disadvantage, and the likelihood of their being able to perform their duties regularly and successfully needs to be examined carefully. Flexibility often requires that preference be given to single applicants who are prepared to live in. However, this group tends to be more job mobile than most, so the policy more or less guarantees a high labour turnover rate. It is up to the rooms division manager to decide to what extent this outweighs the advantages of having staff to hand to cover emergencies. A personnel specification ought to describe the kind of person who could fill the job reasonably satisfactorily, not an ideal candidate who might well turn out to be over-qualified for the job. This means that it is sensible to divide the qualities you are looking for into ‘essential’ and ‘desirable’, since you are unlikely to find many applicants who have everything you could possibly want. A possible human resource management Specification is shown in Figure 63.

Induction

Again, this should be handled by a human relations specialist, but the responsibility may well fall to you in a small hotel. The points to bear in mind are as follows:

![]() The successful applicant should receive a formal letter of appointment. This must satisfy the current employment legislation by giving details of pay, conditions of service, hours, duties, holiday entitlements and any other relevant particulars.

The successful applicant should receive a formal letter of appointment. This must satisfy the current employment legislation by giving details of pay, conditions of service, hours, duties, holiday entitlements and any other relevant particulars.

Figure 63 A personnel specification

![]() The necessary documentation must be processed. This means obtaining the employee's P45 and bank account details, if appropriate. A file should be opened with details of the employee's full name, address and other personal particulars.

The necessary documentation must be processed. This means obtaining the employee's P45 and bank account details, if appropriate. A file should be opened with details of the employee's full name, address and other personal particulars.

![]() On arrival, the new employee should be shown round, introduced to her colleagues and told about any relevant house rules, such as those concerning smoking. The introduction process is particularly important, since this is a ‘people’ industry and you can't expect new staff to welcome customers properly unless the hotel itself sets them a good example.

On arrival, the new employee should be shown round, introduced to her colleagues and told about any relevant house rules, such as those concerning smoking. The introduction process is particularly important, since this is a ‘people’ industry and you can't expect new staff to welcome customers properly unless the hotel itself sets them a good example.

![]() It is equally important to establish a good ‘two-way’ communication link with the new employee at the start. This means explaining what she should do when the inevitable problems arise. Many larger establishments appoint ‘mentors’, whose job is to look after new staff, explain the unwritten rules and informal systems and help them until they have found their feet. A small hotel may not be able to do this: it is all the more important, then, that the supervisor fills the gap.

It is equally important to establish a good ‘two-way’ communication link with the new employee at the start. This means explaining what she should do when the inevitable problems arise. Many larger establishments appoint ‘mentors’, whose job is to look after new staff, explain the unwritten rules and informal systems and help them until they have found their feet. A small hotel may not be able to do this: it is all the more important, then, that the supervisor fills the gap.

![]() Finally, the induction process should identify or confirm any training needs. We will look at how you deal with these in the next section.

Finally, the induction process should identify or confirm any training needs. We will look at how you deal with these in the next section.

An effective induction process pays off because it:

![]() improves the efficiency of newly appointed staff

improves the efficiency of newly appointed staff

![]() improves their morale, and

improves their morale, and

![]() as a result, tends to reduce staff turnover.

as a result, tends to reduce staff turnover.

Staff training

This is really another task for the specialist, but you may not have one in a small hotel. Even in a large one, you will often be called upon to provide detailed training in specific front office procedures for a new employee, so you should have some idea how to go about it.

The first step is to be clear in your own mind what the job involves. This is best done by preparing a job analysis, which is a simple step-by-step list of what each particular task involves. The check-in process, for instance, could be broken down like this:

![]() Make eye contact with guest and smile

Make eye contact with guest and smile

![]() Introduce yourself and ask ‘Can I help you?’

Introduce yourself and ask ‘Can I help you?’

![]() Identify reservation

Identify reservation

![]() Confirm details, using guest's name

Confirm details, using guest's name

![]() Ensure that guest completes registration form

Ensure that guest completes registration form

![]() Obtain credit information (e.g. by noting credit card number)

Obtain credit information (e.g. by noting credit card number)

![]() Assign room and issue key, again using guest's name

Assign room and issue key, again using guest's name

![]() Call porter or direct guest to room

Call porter or direct guest to room

![]() Wish guest a pleasant stay and confirm that you will be at his service throughout it

Wish guest a pleasant stay and confirm that you will be at his service throughout it

Note that although this is a mixture of procedural steps and social skill elements, each stage is observable and measurable on a simple ‘Yes/No’ basis. Phrases such as ‘Be pleasant’ aren't a lot of use, because it is a matter of opinion whether one is being pleasant or not. On the other hand, a smile is unambiguous: you can watch the trainee's lips and see whether the corners of her mouth go up or down.

Many modern hotels have job analyses for every task and position. They may be written in more detail than the one we have just illustrated. In particular, they may include more standard phraseologies like the ‘Can I help you?’ we added to the second step.

Armed with your job analysis, you should then set about the training process. A lot of this is still carried out by getting the trainee to watch an experienced employee dealing with genuine guests (this is traditionally known as ‘sitting next to Nellie’), but it is much better to pick a quiet period and schedule a proper, unhurried training session.

You should be clear in your own mind:

![]() What your objectives are (e.g. to get the trainee to accomplish the task detailed in the job analysis without error).

What your objectives are (e.g. to get the trainee to accomplish the task detailed in the job analysis without error).

![]() How you are going to conduct the session (i.e. what training techniques you are going to use).

How you are going to conduct the session (i.e. what training techniques you are going to use).

![]() How you are going to evaluate the trainee's performance (this is where those ‘Yes/No’ criteria show their worth).

How you are going to evaluate the trainee's performance (this is where those ‘Yes/No’ criteria show their worth).

Training techniques

1 Telling them (i.e. lecturing). This has a part to play, especially in conveying background information, but it doesn't involve the trainee actively and consequently a lot of the material is quickly forgotten.

2 Showing them (i.e. demonstrating). This involves more senses (sight as well as hearing) and is therefore more effective.

3 Getting them to do it (i.e. practice). This involves the full range of senses and is better still as long as the instructor is there to correct mistakes and make sure that the trainee learns to do it the right way.

4 Discussion. This involves answering the trainee's questions. Lots of people are shy about asking questions, either because they are shy or because they find it embarrassing to confess their ignorance. However, you need to encourage them to do so.

5 Role reversal. This involves getting the trainee to teach the instructor. Most lecturers will admit that they only really mastered their subjects when they came to teach them, which shows that trying to teach something is one of the best ways of learning it. Why not make use of that fact?

6 Positive reinforcement. Learning a new skill can be hard, and it is easy to become discouraged. Trainees often reach a ‘plateau’ stage when they don't seem to be able to make any further progress. In fact the foundations for the next step are being laid, but only subconsciously. Trainees need to be helped through this stage. Don't display too much impatience.

Once the training sessions have been completed, the trainee should be given a few trial sessions. Pick quiet periods and (if possible) simple situations. Be on hand to step in if necessary, but try to leave the trainee to complete the whole procedure by herself if possible. If she does, provide positive reinforcement before you offer any minor criticisms.

Training for social skills

Training in clerical procedures is usually fairly straightforward. The real challenge is to improve the employee's all-round social skills performance. We have already suggested that you should incorporate behavioural elements into job analysis. Let us step back, however, and consider how a hotel might tackle the problem in general.

There are two possible approaches:

1 Behavioural

In this, the hotel isolates a particular aspect of staff behaviour and works on that. Some of the ways in which hotels have done this include:

– Self-presentation. Many hotels provide uniforms, and all of them expect a reasonably smart turnout. Some have put mirrors beside the doors leading from staff to public areas, with ‘How will your customers see you today?’ over the top.

– Position, posture and gesture. The Caribbean governments which we mentioned in our chapter on social skills put on various kinds of training courses designed to teach their staff how to appear welcoming to North American visitors.

– Expression. One of the authors of this book once visited an American establishment where all the staff were wearing round yellow ‘smile’ badges in their lapels. When asked why, the guide explained, ‘When our staff visit the washroom, they are expected to adjust their expressions as well as their dress before leaving.’ The badges, which were, of course, visible in the mirror, were there to provide an example of the desired expression. It may only be a gimmick, but if such gimmicks work, use them.

– Eye contact. Although most guests appreciate this, some international hotels have had to warn staff that there are cultures which don't, especially where their womenfolk are involved.

– Speech. We have already discussed the widespread use of standard phraseologies like ‘Have a nice day, now’. Lots of hotels have provided their staff with training in foreign languages. At a simpler level, one notably successful American hotelier was well known for his phrase ‘Contact the hell outa’ them’: his main technique was to make his staff use the guest's name instead of ‘Sir’ or ‘Madam’, and he aimed to have the guest hear that name a dozen times before he had unpacked (the last being a courtesy phone call from reception asking, ‘Is everything to your satisfaction, Mr Vanderbilt?’).

– Non-verbal speech elements. Some hotels have sent staff for elocution lessons (yes, really!).

Look at each of the elements of behaviour in isolation and see how you might improve staff performance.

2 Attitudinal

There is some evidence to suggest that changing one's behaviour can actually affect one's attitude (for instance, if we put on a smile it actually makes us feel better disposed). However, the idea behind inducing attitudinal changes is to make the staff want to be pleasant and helpful so that they modify their behaviour of their own accord.

There are a number of sophisticated techniques designed to bring about the required changes in attitude, and you may well come across them at some time in your career. They include sensitivity training, interaction analysis and T groups. However, these require expert guidance and should be left to qualified professionals.

One of the best known training techniques is ‘transactional analysis’ (usually abbreviated to ‘TA’). This may simplify the psychological processes involved when two people interact, but it helps staff to appreciate how complex customer behaviour can be. That knowledge can help to bring about the desired attitudinal change. TA also provides staff with a set of behavioural clues to other people's states of mind, and easily understood models for their own behaviour.

Appraisal

Modern organizations put a good deal of emphasis on this aspect of human resource management work, and it is undeniably important. Regular performance appraisal interviews:

![]() Help to identify individual strengths and weaknesses, allowing the former to be recognized and the latter to be corrected.

Help to identify individual strengths and weaknesses, allowing the former to be recognized and the latter to be corrected.

![]() Remind the individual of the employer's expectations and, hopefully, encourage renewed commitment.

Remind the individual of the employer's expectations and, hopefully, encourage renewed commitment.

Performance appraisal thus benefits both parties. In a large organization the process is likely to be quite sophisticated. The interviews will be held at regular intervals (yearly is the norm, though some companies conduct them more frequently). The process will involve the completion of an appraisal form, and many organizations ask the employee to complete an initial self-appraisal document as a basis for the interview. The interview itself is a delicate process, and the manager conducting it will probably have received some training in how to do it.

As we have said a number of times in this chapter, this kind of activity will be the business of the specialist in a large organization. However, it could well be yours in a small hotel, which is why we have included it here. The fact that you do not have a human relations specialist available does not invalidate any of the advantages of staff appraisal, so you should try to schedule this as one of your regular responsibilities.

The one difference is that you don't need to make the procedures as formal as they tend to be in larger organizations. To do so might well upset the kind of relationships characteristic of the smaller kind of operation. Even so, it is worth arranging an annual chat with each of your subordinates. Tell them what kind of session it is going to be, but don't make it sound too terrifying. Choose a time when neither of you are likely to be disturbed, and avoid the kind of location which suggests that it will be a confrontational meeting (if you have to use your office, for instance, don't sit behind your desk). A checklist of the topics you should try to cover might look like this:

![]() The employee's personal circumstances. Are there any changes (present or future) which might affect her ability to do the job? If so, can you help?

The employee's personal circumstances. Are there any changes (present or future) which might affect her ability to do the job? If so, can you help?

![]() The employee's performance. If it has been satisfactory, or better than that, then say so. Recognition is one of the strongest motivating factors of all. Try to lead up to any shortcomings as tactfully as possible, and, if possible, get the employee to volunteer them first.

The employee's performance. If it has been satisfactory, or better than that, then say so. Recognition is one of the strongest motivating factors of all. Try to lead up to any shortcomings as tactfully as possible, and, if possible, get the employee to volunteer them first.

![]() Training needs. It is much better if these can be identified jointly.

Training needs. It is much better if these can be identified jointly.

![]() Employee's suggestions. If the interview isn't a ‘two-way’ process, then you have wasted an opportunity. Staff see more of what is going on at their level than you do, and they often have useful ideas. Of course, they can also use the interview as an opportunity to air petty jealousies, but it is useful to know about these as long as you don't take sides.

Employee's suggestions. If the interview isn't a ‘two-way’ process, then you have wasted an opportunity. Staff see more of what is going on at their level than you do, and they often have useful ideas. Of course, they can also use the interview as an opportunity to air petty jealousies, but it is useful to know about these as long as you don't take sides.

![]() Pay. Good work calls for some reward.

Pay. Good work calls for some reward.

![]() Prospects. Small operations might not offer a lot of scope for promotion, but if there is any, it is worth mentioning it. People like to know where they stand.

Prospects. Small operations might not offer a lot of scope for promotion, but if there is any, it is worth mentioning it. People like to know where they stand.

Properly conducted, this kind of discussion helps to clear the air of any misunderstandings and should lead to a happier, better-motivated staff.

Discipline and dismissals

Unfortunately, staff do not always behave as you would like, and you may have to face up to the disagreeable necessity of disciplining them. It is particularly important that you handle this correctly, since the employee can take the case to an industrial tribunal if you don't. Make sure you keep up with developments in employment law.

In broad terms, disciplinary offences can be divided into:

1 Minor infractions. These include lateness or absenteeism, poor job performance and the kind of disobedience which doesn't create a safety hazard or offend a guest. This kind of problem should be dealt with by a series of warnings:

– Verbal warning

– Written warning

– Final written warning, and then

– Dismissal.

2 Infractions justifying instant dismissal. These would include dishonesty, abusing or assaulting guests, the wanton destruction of hotel property, or any conduct which creates a serious safety hazard. Disobedience as such isn't necessarily a valid cause: you need to allow for the employee's state of mind and any possible provocation she may have suffered.

This last point underlines the need to have an effective grievance procedure. Once again, large companies formalize these, whereas the problem is best handled informally in a small one. You should make sure that there is some outlet, however: it's much better to listen than to let grievances fester.

Assignments

1 Prepare outline organization charts for the Tudor and Pancontinental Hotels.

2 Assign staff names to the front office posts you have designed for the Pancontinental, and prepare a specimen four-week duty rota.

3 Prepare a job analysis to cover the steps required to deal with a guest who is leaving after a one-night stay.

4 Prepare a five-day training programme for a new receptionist in a medium-sized hotel using a computerized front office system. Your programme should detail the training session periods (with breaks), the aims of each session and the techniques you propose to use.

5 ‘It is easier to teach procedures to someone who is naturally hospitable than to teach hospitality to someone who knows the procedures.’ Discuss this statement in relation to front office.