Chapter 11

Tariffs

Introduction

So far, we have said little about the way in which a hotel decides how much to charge for its accommodation. This is clearly something which affects its marketing policy and is likely to play an important role in the negotiating process we outlined at the end of the last chapter.

Tariff construction is not likely to concern the majority of front office staff very closely. However, it IS a matter for the front office manager, and you ought to have some understanding of the principles.

There are two fundamental methods of approaching the problem:

1 Cost-based pricing. In these systems, the tariff is designed to cover the basic costs of operation at a given level of service, plus a given rate of return.

2 Market-based pricing. These systems start from an idea of what the customer is prepared to pay and use this as a starting point. The hotel then tries to tailor its costs so that it achieves a reasonable rate of return on that basis.

Of course, no hotel can determine its costs without having some idea of what the customer wants by way of service, so even cost-based pricing contains an important market element.

There is evidence that the hotel industry is divided into ‘price makers’ and ‘price takers’. The former (usually the larger market leaders) use a sophisticated cost-based approach combined with market research techniques to determine the optimum price levels for their hotels. The latter (usually the smaller operators) then compare their establishments with those of the price makers, and adjust their prices accordingly. In other words, they look at what their larger neighbours are offering, and then say, ‘If the Superbe is charging £50 per night for a modern room with a good view and every possible facility, we can't ask more than £35 for our less attractive ones...’ This is effectively market-based pricing.

Let us look at these different approaches.

Cost-based pricing

The 1:1,000 rule

This is the simplest of the cost-based systems. It states that you should charge approximately £1 per night for every £1,000 of room cost. It works in other currencies, too. If your room cost was $100,000, your room rate should be around $100 per night, and if your costings were in Japanese Yen, about ¥100.

The rule was devised quite a long time ago, when rates of interest and expectations about appropriate rates of return were very different, but it still reflects the fundamental importance of fixed costs in determining a hotel's profitability. If you build a hotel in a major metropolitan city centre like London, you have to pay a high price for the land. This forms a major part of the room cost, which might well exceed £200,000. As the 1:1,000 rule indicates, you would then have to charge around £200 per night to have any chance of recovering your investment. This helps to explain London room rates.

‘Room cost’, incidentally, includes the cost of the public areas as well, which are averaged out over the rooms as a whole. Essentially, the calculation is:

The 1:1,000 rule ignores inflation, but it is obvious that this needs to be taken into account. Many of the rooms built at the beginning of the twentieth century cost a few hundred pounds each rather than tens of thousands. It would be ludicrous for such hotels to be charging 50p per night today. In applying the rule, therefore, it is better to take the current cost of building an equivalent room rather than the (possibly misleading) historical cost.

With this reservation, the rule still offers a rough and ready guide to hotel prices. It is not at all precise, but if you know (say) that a group with a number of hotels totalling 1,000 rooms has just been bought for £60,000,000, then you can assume with some confidence that the average room rate will be closer to £60 per night than £40 or £80.

The Hubbart formula

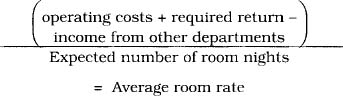

The Hubbart formula is a method of establishing an average room rate for a new hotel. The basic calculation is:

It is rather more complicated than this in practice, but there is still nothing particularly difficult about it. The steps are as follows:

1 Take the total amount invested in the hotel (this will include both share capital and any long-term loans such as debentures) and decide on the rate of return required on this investment.

2 Estimate the overhead expenses (interest, administration, heating and lighting, repairs and the like) for the next year.

3 Combine 1 and 2 to find the required gross operating income (in other words, the amount you need to make to cover your expenses and keep your investors satisfied).

4 Estimate the probable profits from all other sources other than rooms (i.e. restaurant, bars, health clubs, concessionary shops and the like).

5 Deduct 4 from 3 to find out how much profit you need to make from room lettings.

6 Estimate the accommodation department's expenses for the next year.

7 Add 5 and 6 to find out how much you need to make from the rooms.

8 Estimate the number of room nights you are likely to achieve per annum (this may be established by taking regional Tourist Board averages for comparable hotels).

9 Divide 7 by 8 to find out the average room rate you should charge.

Let us take a practical example.

Mike Allott has bought a plot of land in order to build a motel on it. His architect calculates that he can fit twenty rooms onto the site, plus appropriate car parking and access routes, a restaurant, a small swimming pool and the necessary stores and offices. He estimates that the land and buildings will cost him £500,000, the fixtures and fittings another £100,000, and that he will need another £10,000 for initial working capital. He proposes to borrow £50,000 by means of 12 per cent debentures and to raise the remainder of the capital required by issuing shares at a premium.

Mike decides that he wants a return of 18 per cent on his investment, though he recognizes that about a third of this will be taken in tax. He prepares estimates of the operating costs, etc. and goes on to calculate the required average room rate (see following page).

You will notice that this average room rate bears out the 1:1,000 rule. The room cost was about £30,000 (total cost £600,000 divided by 20), and the rule predicts that the average room rate should be around £30. Our example may seem a little contrived, but we have used fairly ‘standard’ ratios in preparing Mike's forecasts for him, and even if we changed some of these we would still expect the result to be somewhere in a range of £25 to £35 per night. This suggests that the 1:1,000 rule still has some validity.

Differential room rates

The 1:1,000 rule and the Hubbart formula only produce average room rates. These do not allow for the fact that the price often has to vary according to the type of room (e.g. single, twin, etc.), its facilities (size, furnishings, accessories, location, noise, etc.), and the number of people occupying it.

| Balance sheet figures: | ||

| Total investment: | ||

Fixed assets |

600,000 | |

Working capital |

10,000 | 610,000 |

| Total capital employed: | ||

Share capital |

500,000 | |

Share premium account |

60,000 | |

12% debentures |

50,000 | 610,000 |

| Room rate calculations: | ||

Required net profit before tax: |

||

Required return less tax |

67,200 | |

Tax at 30% |

28,800 | 96,000 |

| Operating costs: | ||

12% debenture interest |

6,000 | |

Operating expenses |

27,900 | |

Property expenses |

25,600 | 59,500 |

| Required gross profit: | 155,500 | |

| Less profits from other depts: | ||

Food |

15,000 | |

Bar |

34,000 | 49,000 |

| Required profit from rooms | 106,500 | |

| Estimated rooms expenses | 45,000 | |

| Required room income | 151,500 | |

| Estimated room nights p.a. | ||

(20 rooms @ 70% occupancy for 365 nights) |

5,110 | |

| Required average room rate | 30 |

These considerations affect most hotels, so the calculation of an average room rate is usually only the first step in the process of tariff creation. It needs to be broken up in order to offer differentials between different room types. Let us consider this problem with the aid of another example.

Let us assume that we have taken over an old and somewhat run-down hotel, refurbished it, and now have to work out a new tariff. The hotel has the following rooms:

| 20 singles | (washbasins and showers) |

| 30 doubles | (washbasins and showers) |

| 10 de luxe doubles | (bathrooms en suite) |

Our Hubbart formula calculations tell us that the average room rate ought to be £35 per night. Our problem is to work out what the rates should be in detail. Our initial choice has to be between a ‘per room’ and a ‘per guest’ rate. In this situation we would probably choose the former, since the rooms vary in terms of size and amenities. Two singles offer rather more than one double, and a single person occupying a double room would have more space at his disposal. A simple ‘per guest’ rate would ignore these considerations and lead to some guests feeling disadvantaged while others felt they had got a bargain.

However, we can't begin to work out suitable rates without having some idea of the probable occupancy figures. These are likely to vary according to the type of room. Let us assume that our estimates are as shown in Table 11.

As you can see, we have had to allow for the fact that the double rooms can be let to singles as well as couples (they might even sleep more if we added cots or ‘Z’ beds, but we will ignore that complication).

We have also had to allow for the fact that we have a different number of rooms of each type. A 10 per cent change in the doubles occupancies would have more effect on the overall rate than a 20 per cent change in the occupancy of the de luxe doubles, simply because there are three times as many of the former.

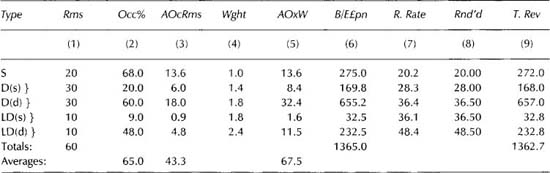

Table 11 Estimates of room occupancy

| Type | Rooms | Occupancy (%) | |

| S | (single, single occupancy) | 20 | 68.0 |

| D(s) | (double, single occupancy) | 20.0 | |

| D(d) | (double, double occupancy) | 30 | 60.0 |

| LD(s) | (Luxe D, single occupancy) | 9.0 | |

| LD(d) | (Luxe D, double occupancy) | 10 | 48.0 |

| Total rooms | 60 | ||

| Average occupancy | 65.0 | ||

Table 12 Suggested room weightings

| Type | Rms | Occ% | AOcRms | Wght |

| S | 20 | 68.0 | 13.6 | 1.0 |

| D(s) } | 20.0 | 6.0 | 1.4 | |

| D(d) } | 30 | 60.0 | 18.0 | 1.8 |

| LD(s) } | 9.0 | 0.9 | 1.8 | |

| LD(d) } | 10 | 48.0 | 4.8 | 2.4 |

| Total | 60 | |||

| Averages | 65.0 | 43.3 | ||

In order to arrive at a suitable rate per night for each type of room, we have to decide on appropriate ‘weightings’. In other words, if a single room cost (say) 1, how much more would we expect to pay for a double? These weightings are very much a matter of judgement. However, most people seem to agree that a single person occupying a double should pay more than the standard single rate (after all, he has more space) but not the full double rate, and that a double should normally cost rather less than twice the single rate (it doesn't cost twice as much to service, for one thing), so our proposals are as shown in Table 12.

Now, our original target revenue per night must have been £1,365 (£35 average rate x 60 rooms x 65 per cent occupancy rate). Our problem is to split up the average rate in a way which will reflect the varying number of rooms, the different occupancy rates and the differential weightings, so that the actual revenue still comes to the required £1,365 per night. A possible way to do it is shown in Table 13.

The meaning of the various columns in Table 13 is as follows:

(1) The number of rooms of each type. There are two kinds of occupancy to consider as far as the doubles and deluxe doubles are concerned, but the total number of rooms remains the same at sixty.

(2) Room occupancy percentages (as before).

(3) Average number of rooms occupied per night. The calculation is:

![]()

In the case of the doubles and de luxe doubles, the combined total of occupied rooms cannot exceed the total number of rooms of that type (i.e. thirty and ten respectively).

Table 13 Revenue from weighted rooms

(4) Weights as previously decided.

(5) Average occupancies times weights, or (3) x (4). This produces a combined weighting which reflects both the ‘value’ of the room and the expected occupancies.

(6) This divides the required nightly revenue of £1,365 in the proportions shown by Column (5). For example, the singles figure is calculated as follows:

![]()

and so on. The point of this is to find how much each room type needs to contribute to the nightly target, given its expected occupancy and its ‘weight’.

(7) This establishes how much each individual occupied room needs to contribute to the target. We find this by dividing the total target figure for the room type (this is what we calculated in Column 6) by the number of occupied rooms (Column 3). The singles figure, for example, is calculated as follows:

![]()

You will notice that the room rates we obtain still bear the same relationship to each other as the original weightings. The de luxe doubles, for instance, are still 2.4 times as expensive as the singles.

(8) This simply rounds off the figures in Column (7) to acceptable sums. Your decisions here might not be exactly the same as ours, but that doesn't matter very much.

(9) This calculates final revenue total per night in order to check that our rates do actually achieve something close to the target figure. Because of the rounding-off process in Column (8) our final total isn't exactly £1,365, but this doesn't matter as long as it is reasonably close. After all, most of the original figures were only estimates anyway.

All this can be done on a spreadsheet. It may take an hour to set up, but you can file this and use it again. For instance, if your target revenue figure changed you could easily recalculate your rates, or revise them on the basis of different weightings if the latter turned out to be wrong.

Seasonal rates

Another of the problems that an average rate doesn't deal with is that of seasonality. Almost all hotels experience some fluctuations in occupancy levels at different times of the year, and these are particularly marked in the case of resort hotels. Setting a low one during the off season helps to attract business, while setting a higher one during the busy season maximizes profit.

Some specialized kinds of operation (hire boats, for instance, or holiday camps) have a wide range of different rates, with the main holiday periods attracting the highest ones, but hotels generally have fewer. The most common approach is to have high and low season rates. In Europe the high season is in the summer, but it is the other way round in tropical holiday areas like the Caribbean where tourists go to escape the northern winter.

We face the same problem with seasonal rates as we did with different room types, and we can use the same approach. Indeed, we can even combine the two. Let us extend our last example to see how.

You will remember that we had estimated average annual occupancies for each type of room. In practice, these would vary from week to week, being relatively low in the winter (possibly with an increase around Christmas), and higher in summer.

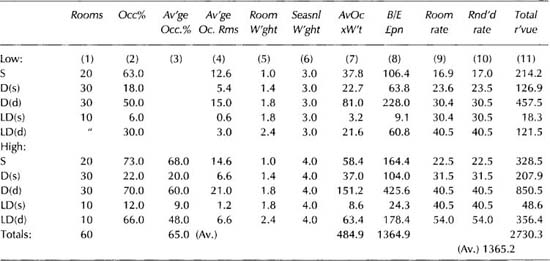

Table 14 Room occupancies for high and low seasons

| Rooms | Low (%) | High (%) | Average occupancy (%) | |

| s | 20 | 63.0 | 73.0 | 68.0 |

| D(s) } | 30 | 18.0 | 22.0 | 20.0 |

| D(d) } | 50.0 | 70.0 | 60.0 | |

| LD(s) } | 10 | 6.0 | 12.0 | 9.0 |

| LD(d) } | 30.0 | 66.0 | 48.0 | |

| Total | 60 | |||

| Averages | 56.5 | 73.4 | 65.0 | |

Let us assume that there are two reasonably clearly marked seasons, a low and a high. Let us also assume for the sake of convenience that each of these lasts six months (October to March, say, and April to September). The occupancies for the different types of room might then break down as shown in Table 14.

As before, the averages take account of the fact that there are differing numbers of each type of room.

You will notice that the seasonal differences are greater for some types of rooms than for others. In the case of the de luxe doubles, for instance, the summer occupancies are twice as high as the winter ones, whereas the increase in the singles occupancies is nowhere near as great. This may well lead you to think about raising the differential in the case of the former by more than for the latter. However, to keep things simple, let us assume that you decide that each summer rate should be a third higher than the winter one.

The problem is how to divide up our set of average room rates so that they reflect this difference while still achieving the target revenue figure of £1,365. Fortunately, we can use the same ‘weighting’ technique that we have already outlined above. Even more fortunately, we can combine the two sets of calculations, as shown in Table 15.

This looks fairly formidable, but it is in fact only an extension of the technique we used earlier. What we have done in addition is to combine the two kinds of weighting, so that the final figure reflects both the relative ‘value’ of the rooms and the seasonality factor. The columns are calculated as follows:

1 Actual number of rooms, as before. Once again, note that the double and de luxe double figures have to reflect two types of occupancy, but that the total of available rooms remains sixty.

2 Occupancy percentages, this time divided into low and high.

3 Annual average occupancy percentages for each type of room. There is only one figure for each type of occupancy because there can only be one annual average! It is only incorporated as a check on the accuracy of the seasonal figures, and we won't be using it in the subsequent calculations. The calculation in this particular case is quite simple, but it would be slightly different if you had seasons of different lengths. This is easy to demonstrate:

Table 15 Seasonal revenue from weighted rooms

(a) 6 month high season

6 month low season

![]()

(b) 4 month high season

8 month low season

![]()

4 Average number of rooms occupied per night for each type of occupancy. The calculation is:

![]()

5 Weights as previously agreed.

6 Seasonal weightings. As already noted, we decided that the high season rates should be a third higher than the low season ones. This is achieved by giving the former a weighting of 4 and the latter a weighting of 3.

7 Average occupancies times both weights, i.e. (4) x (5) x (6). This produces a combined weighting which reflects the probable occupancy, the ‘value’ of the room, and the seasonal weighting.

8 This divides the required nightly revenue of £1,365 in the proportions shown by Column (7). The low season singles figure is calculated as follows:

![]()

and so on. This works out how much each type of room should be contributing to the nightly target.

9 This shows how much each occupied room needs to contribute. We find this by dividing the total contribution for the type (Column 8) by the actual number of occupied rooms (Column 4). The low season singles figure, for example, is calculated as follows:

![]()

You will notice that the resulting room rates within each of the two seasons still bear the same relationship to each other as the original weightings (the de luxe doubles, for instance, are still 2.4 times as expensive as the singles). Moreover, the high season rates are almost a third higher than the low season ones, which is what we wanted.

10 Again, we have rounded off the rates in Column (9) to produce psychologically acceptable figures. This is a question of judgement, and your decisions may not be the same as ours, though in this particular case the answers are fairly obvious.

11 This column confirms that the various rates will actually produce the required average annual nightly revenue target figure. The calculation is occupied rooms (Column 4) times the rounded off room rate (Column 10). The only point to note is that the final total (£2,730.3) has to be divided by 2, since each separate rate only applies for a six-month period (i.e. half the year). This produces our Hubbart formula starting point of £1,365 per night, which is an average of both the low and high seasons. If you had seasons of unequal length, this calculation would have to be modified along the lines suggested in point 3.

Weekday/weekend rates

As a general rule, weekday (usually Monday to Thursday) occupancies are higher than weekend (Friday to Sunday) ones, especially in business hotels. This is sometimes known as a ‘four-sevenths’ pattern.

Hotels may differentiate between weekdays and weekends for the same reason as they use seasonal rates. Differential rates maximize revenue when demand is high, and encourage occupancy when it is low.

The problem as far as rate setting is concerned is the same as before, and the technique we have already described could be extended if necessary. You would have to decide how much more the weekend rate should be as compared with the weekday one, and then introduce an appropriate weighting. You might decide, for instance, on a proportion of 2:3 (in other words, with the weekend rate only two-thirds of the weekday one). You would then have a table with four separate blocks of rates (low/weekend, low/weekday, high/weekend, and high/weekday). This would be rather complicated, especially since you would have to allow for the fact that the total number of weekend nights is different from the total of weekday ones (there are 156 weekend nights and 208 weekday nights, plus one which might be either).

In practice, few hotels would use differential weekend rates calculated in this way, since they complicate the tariff structure and make billing more difficult. However, there is a case for differential weekend rates where the weekday and weekend business are self-contained and mutually exclusive. Some years ago enterprising hotels decided to promote ‘weekend packages’ in association with the major tour operators. The method they used to price these is described in the next section.

Marginal or contribution pricing

Traditional cost-based pricing tries to make sure that revenue covers the total costs plus the target profit. Marginal pricing is aimed at ensuring that the price charged for any individual service covers the variable (i.e. extra) cost of providing that service plus a contribution to the establishment's fixed costs.

Marginal pricing is particularly suited to what have been described as ‘secondary pricing decisions’, which means any supplementary business such as special weekend packages, occasional conferences and the like. One example might be the ‘four-seventh’ type of hotel, where the main market is the weekday business traveller. The hotel still has to remain open over the weekend, however, and thus incurs costs. Some of these (like staffing) can be reduced, but overheads such as depreciation remain unaffected. If the establishment can create new weekend business, these overheads can be ‘spread’ over a larger number of customers.

It is usually impossible to attract such weekend business at the normal weekday prices, which means that these will have to be reduced. The aim of marginal pricing is to make sure that they still cover the variable costs, together with a contribution towards the fixed costs. The actual size of this contribution is often secondary: the basic idea is to fix the selling price so that it is attractive enough to bring in some additional business and thus make some contribution.

Let us consider a simple example. As you know, variable costs usually form a very small proportion of the expenses of letting an additional hotel room. They involve little more than the laundry charges and a few disposables such as soap. Strictly speaking, direct labour is only a semi-variable (you don't normally take on an extra receptionist to deal with one extra guest, though you may have to in order to deal with twenty), though it is usually included as well. Even with labour included, the variable costs do not usually amount to much more than 25 per cent.

Let us assume that these variable (direct) costs are 25 per cent, and that our normal (i.e. weekday) rack rate is £40. Our figures would then look something like this:

| Normal room rate | £40 |

| Less variable costs | £10 |

| Normal contribution | £30 |

If we can obtain more than £10 for our room at the weekends, then we are getting a contribution towards the fixed (overhead) costs. If we charged £15, for instance, we would get a contribution of £5. It may not sound much, but it is a great deal better than nothing at all. The ‘floor price’ (i.e. the minimum we could charge) would be £10, the ‘ceiling price’ (i.e. the maximum) usually not more than £40 (the normal rate). This gives us a range of possible prices which provides a lot of scope to develop a flexible pricing strategy, and even to explore totally new markets.

Marginal pricing can be used to advantage in the following situations:

![]() Where rooms are otherwise likely to remain empty.

Where rooms are otherwise likely to remain empty.

![]() In any situation where there are rapid and marked fluctuations in demand, making the uniform rack rate inappropriate (in these circumstances marginal pricing will at least tell you the lowest price you can afford to charge).

In any situation where there are rapid and marked fluctuations in demand, making the uniform rack rate inappropriate (in these circumstances marginal pricing will at least tell you the lowest price you can afford to charge).

![]() Where you are quoting a price on a ‘one-off’ basis, especially in a competitive situation.

Where you are quoting a price on a ‘one-off’ basis, especially in a competitive situation.

The areas where marginal pricing is most likely to be useful are thus weekend breaks, off-season holidays, conferences and special events. Hotels have also been known to respond to last minute enquiries by reducing their prices (airlines follow the same reasoning with regard to unsold seats), which amounts to the same thing.

Generally, marginal pricing should only be used as a supporting technique, since it does not offer any guarantee that all the fixed costs will be covered. It should therefore be combined with some other form of cost plus pricing. One approach might be to rely on the staple business (in our case, the Monday to Thursday guests) to cover the basic costs (all the fixed costs plus the variable ones incurred by that business), and use the weekend business to provide the extra ‘jam’.

There are, of course, problems associated with marginal pricing, notably the difficulty of establishing just what the variable costs actually are (especially in small businesses), the risk that frequent price changes may affect customer goodwill and thus repeat business, and the difficulty of deciding just what price level will maximize demand. These last two considerations lead us on to a consideration of market pricing.

Market pricing

Price- taking or ‘price followership’

Many smaller hotels simply ‘follow’ the prices established by their larger competitors by keeping their own rates 10-20 per cent below theirs.

Strictly speaking, this is competitor-based pricing, but since the ‘pricemaker’ will have taken what the market will bear into consideration, it is also a form of market-based pricing. It is a mechanism for updating the 1:1,000 rule as well: the price-makers tend to be the newer hotels, so price following keeps rates in the older establishments in line with current construction costs.

Price taking does not take any account of the follower's operating costs. If the price-maker is much more efficient (through better room design reducing heating costs, for instance), this puts the price-taker in the difficult position of having to cover relatively higher overheads with relatively lower revenue.

‘Top-down’ pricing

This approach is often used by companies proposing to enter a new market. It starts by identifying a ‘gap’ which is currently unfilled. One might look at an old-fashioned resort town, for instance, and find that while there are one or two traditional hotels and a lot of smaller private ones and boarding houses, there is no medium-sized modern establishment with a conference centre and rates which fit somewhere in between the two levels available.

Once this market opportunity has been identified, the procedure is very similar to that used in the Hubbart formula. The main difference is that we now start ‘at the top’ by establishing how many rooms we think we can let per annum at the given rate, and then working downwards through the cost figures to see whether these will result in an acceptable rate of return.

If our calculations do not result in an acceptable return, then the costs must be re-examined. It may be that reductions can be made in building costs, or staffing ratios can be reduced, or a greater contribution obtained from the restaurant.

It might be argued that ‘top-down’ pricing is really cost-based, because ultimately it is still the costs which decide whether we can achieve an acceptable rate of return. However, it puts the emphasis firmly on what the customer wants, and stimulates innovative thinking about the various cost elements, rather than taking these as fixed.

The most radical example of this approach is the Japanese ‘cubicle’ hotel, introduced after research had shown that Japanese customers wanted cheaper city centre overnight accommodation and would not mind sleeping in self-contained insulated cylinders with communal washing facilities as long as these cost only 25 per cent of the usual room rate. Here the sequence of thinking began with the question ‘How can we provide accommodation at a quarter of the usual city centre room rate?’, and came up with the answer ‘Pack four times as many guests into the same space’.

Rate cutting

Most hoteliers assume that demand will increase if prices are lowered. However, rate cutting can be a risky expedient, because the increases in occupancy needed to offset the drop in revenue are surprisingly high, as Table 16 demonstrates.

Many of these increases are clearly unobtainable, even though a hotel can sometimes achieve more than 100 per cent by bringing additional beds and rooms into play.

A unilateral cut may begin a round of competitive rate cutting which would end up in everyone making losses and the weaker hotels (possibly yours, especially since you were the one who felt the need to start it in the first place) going to the wall. This is why the industry as a whole frowns on what is sometimes called ‘discounting’.

Prestige product pricing

It is not always true that demand will increase if prices are lowered. Raising them may well make the hotel more exclusive and thus change the nature of the product (marketing people explain this in terms of ‘product differentiation’). This means that hotels can sometimes increase occupancies by raising their prices, in apparent defiance of the laws of economics.

Table 16 Occupancies required to offset rate cuts

The orthodox explanation for this phenomenon is that guests are unable to discern a hotel's ‘quality’ in advance and so use the quoted price as an indicator, arguing, ‘It's very expensive so it must be good!’ This may be true enough as far as new guests are concerned, but it hardly explains why such a hotel is able to retain its customers. It seems more likely that the hotel is genuinely providing something extra in return for its high prices, over and above the obvious features of five-star service. We suggest that there are two closely linked elements to this:

1 Firstly, the fact that the guest can afford the price asked demonstrates his relatively high economic (and thus social) status, and consequently satisfies his need for ‘esteem’.

2 Secondly, the high prices effectively keep out persons of lower economic standing, thus underpinning the hotel's image of social exclusiveness.

This exclusiveness can be thought of as an important element of the total ‘package’, and the high prices necessary to maintain it are both its cause and its justification.

It is said that when the first modern hotels were built in Central London after the Second World War their initial occupancies were disappointing, and that it was only after they increased their rates so that they were in line with the older, higher cost establishments that occupancies picked up. Although their initial rates were actually based on lower costs, these were perceived (rightly or wrongly) as reflecting lower quality.

This strategy will only succeed where the market is not particularly price-conscious. It can work for a luxury cruise ship, for instance, but not for the cheap weekend market. It underlines the fact that pricing is very much a psychological activity.

Because of this, prices are often modified to convey particular messages. £59.50 sounds much lower than £60 than it really is, and £105 can ‘signal’ prestige and quality much more clearly than £95. This is why we added a ‘rounding’ column to our earlier tables.

Inclusive/non-inclusive rates

Before we finish, we need to consider whether to include meals in our rates. There are four main kinds of tariff available:

1 Fully inclusive (room plus all main meals). This is the European ‘En Pension’ or ‘Full Board’ rate, also known as ‘American Plan’ because nineteenth-century US hotels often catered for long-stay full-board residents.

2 Semi-inclusive (i.e. room plus breakfast and one main meal, usually the evening one). This is the European ‘Demi-Pension’ or ‘Half Board’, also called ‘Modified American Plan’ or ‘MAP’.

3 Bed and Breakfast CB&B’). This is self-explanatory.

4 Non-inclusive rate (i.e. a separate charge for each item such as room, meals, drinks, extras, etc.). This is often known as ‘European Plan’ because it was characteristic of the large European hotels Americans stayed at on their travels.

No rate can ever be fully inclusive, because guests vary so much in their requirements. Some drink a lot, others don't. Some will make a lot of use of the telephone or laundry while others won't. All these are extras which will have to be charged for separately. ‘Inclusive’ is thus a relative term.

The question is, what kind of approach to adopt? This depends upon two factors.

Guest characteristics

The tariff type has to be related to the guests’ own requirements. The main factors affecting these are as follows:

1 Length of stay. An airport hotel can't even be sure that its guests will stop for breakfast. Most hotels find that overnighters want an evening meal, although longer stays may not wish to be tied down to a single restaurant (this is why large modern hotels often offer a range of ‘meal experiences’). Really long-term stays (like those at spa hotels) tend to regard the hotel as ‘home’ and only eat out occasionally.

2 Spending power. An inclusive tariff implies a table d'hôte menu with a restricted range of dishes all costing more or less the same to produce. Since such menus offer the advantages of economies of scale, they are usually cheaper and thus appeal to customers with relatively low purchasing power. By contrast, more upmarket customers are accustomed to a wider range of choice and are prepared to pay for this.

3 Homogeneity. The standardization implicit in inclusive rates is more acceptable if all the guests have similar backgrounds. This is characteristic of holiday camps, group tour business and conventions.

4 Predictability. This means the extent to which the guests’ requirements are likely to vary from night to night. A business traveller may eat a plain, solitary meal one evening, then entertain a group of clients lavishly the next, which makes an inclusive tariff awkward to operate.

Hotel characteristics

Some hotels are more likely to operate inclusive tariffs than others. The main considerations are:

1 Grade. A five-star hotel has a higher staff:guest ratio than a cheaper one. The extra staff make it easier for such hotels to produce itemized bills.

2 Size. This means that the cost of equipment such as expensive computers and point of sale terminals can be spread over a larger number of customers. Moreover, the larger the hotel, the more sophisticated its costing system needs to be, and this also tends to lead to itemized bills.

3 Type of business. The longer stays characteristic of resort hotels increase the relative burden of itemizing every separate charge. If a guest incurs four charges a day (room, breakfast, lunch and dinner) and stays for seven days, his bill will be at least twenty-eight items long. This could be reduced to only one by using an inclusive weekly rate.

4 Location. Guests at isolated hotels are more or less forced to eat there. On the other hand, a hotel situated in the centre of a city's restaurant district has little chance of ‘holding’ its guests for more than one night (one imaginative solution is to provide vouchers which the guests can use at a variety of local restaurants).

5 Marketing considerations. An inclusive rate helps to ‘fix’ guests as far as the restaurant is concerned. This can be important in smaller hotels (where the unexpected absence of a few guests can seriously upset restaurant calculations) and those working on very narrow margins. Hotels offering inclusive rates sometimes offer ‘meal allowances’, which permit guests to choose either the standard table d'hôte menu or to set off the cost against an a la carte meal. This encourages them to take advantage of the latter's wider choice because they feel they are getting a substantial allowance towards the cost, and thus helps to increase restaurant sales figures.

Turning a room rate into an inclusive rate, is easy enough in principle because all you have to do is add the meal prices to the room rate. However, you have to remember that double occupancy means two sets of meal charges, which is why most inclusive rates are ‘per person’.

If you operate an inclusive rate, you also have to decide on whether to make an allowance if the guest does not consume a meal, and how to check this. Breakfasts used to be a particular problem: receptionists had little option but to take an early check-out's word that he had not had time for breakfast and make an appropriate deduction, and some guests took advantage of this. One of the advantages of electronic point of sale billing is that it reduces this possible fraud.

Conclusion

To sum up, room pricing is a complex business which requires both a knowledge of costs and a good deal of psychology.

Assignments

1 Compare the tariffs likely to be found in the Tudor Hotel with those of the Pancontinental. Which is the more likely to include inclusive elements?

2 Paragon Hotels are considering building a 150-room hotel in a city centre location. The estimated building costs are £5,000,000, the fitting-out costs £2,000,000, and the working capital required £500,000. The project will be financed by borrowing £6,000,000 at 15 per cent per annum and providing the remainder from internal sources.

Paragon's policy is not to undertake any new investment unless the overall return is 15 per cent net of tax (currently 30 per cent on net profits).

The annual operating expenses are estimated to be £2,500,000, the food and beverage contribution to be £400,000, and the room servicing costs to be £300,000. The hotel will be open all year round and the average occupancy is expected to be 75 per cent.

Calculate the average room rate using the Hubbart formula.

3 Paragon Hotels have just acquired the Queen's Hotel, which has the following characteristics: Rooms:

15 singles with shower

15 singles with bath

20 doubles/twins with shower

20 doubles/twins with bath

5 luxury doubles/twins

Expected clientele:

30% business (year round, mainly S, stay 1/2 nights)

20% transit (year round, mixed S/D, stay 1 night)

20% touring (seasonal, mainly D, stay 1 night)

20% resort-based (seasonal, mainly D, stay 4/7 nights)

10% group (seasonal, mixed S/D, stay 2/3 nights)

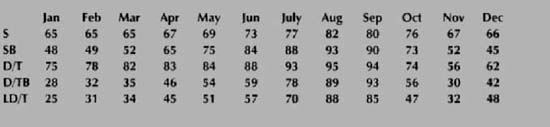

Studies suggest that average monthly occupancy percentages will be as in the table below.

These figures can be assumed to be consistent over the probable price range.

Friday-Sunday occupancies are likely to average 60 per cent of Monday-Thursday ones.

Table d'hôte meal charges (exclusive of liquor) are expected to be as follows:

Breakfast |

£3.00 |

Lunch |

£6.00 |

Dinner |

£9.00 |

Room revenue is required to cover operating expenses plus overheads, together amounting to £400,000 per annum, plus a profit of 20 per cent (ignore tax).

Design a suitable tariff and demonstrate that this will meet the prescribed accommodation revenue target on the basis of the information given.

4 You have a thirty-bedroom hotel with a low weekend occupancy. A neighbouring hotel has operated weekend packages (i.e. full board for two days) successfully at £40 per person over a six-month (i.e. 26-week) period. You would like to enter this market. You estimate that the costs to be taken into consideration are as follows:

Food £8 per person per day

Laundry and other direct guest costs £6 per day

Additional part-time staff 30 hours at £2.00 per hour

Fixed cost allocation £5,000

Advertising and promotion £5,000

Propose a suitable package rate and demonstrate the average occupancy level at which this will:

(a) Break even.

(b) Yield a net profit of £2,000 over the period.

5 It is said that some hotels can actually increase demand for their services by raising their prices. How far is this true of hotels as a whole, and what is the explanation?