Cultural Intelligence and Levels of Readiness

The third and final variable in the model represents an overall level of readiness to communicate in ways that are beneficial to global organizational learning. We use the concept of cultural intelligence (abbreviated as CQ) (Ang and Van Dyne, 2008; Early and Ang, 2003) to explore the characteristics of individuals who are more likely to have the capability to overcome the communication barriers to organizational learning in MNCs described above.

Cultural intelligence is conceptualized as having four main dimensions: meta-cognitive, cognitive, motivational, and behavioral (Ang and Van Dyne, 2008). Meta-cognitive CQ refers to the ‘individual’s level of conscious cultural awareness during cross-cultural interactions. People with strength in meta-cognitive CQ consciously question their own cultural assumptions, reflect during interactions, and adjust their cultural knowledge when interacting with those from other cultures’ (Ang and Van Dyne, 2008: 5). It can thus be seen as a higher-order cognitive process. Cognitive CQ, on the other hand, is more concerned with understanding how cultures differ and includes knowledge of the norms and practices of other cultures that a person accumulates through study or personal experience. Motivational CQ refers to the ‘capability to direct attention and energy toward learning about functioning in situations characterized by cultural differences,’ that is, being willing to expend the energy to understand cultural differences, often due to intrinsic interest. Finally, behavioral CQ is the willingness to engage in actions, both verbal and non-verbal, that are different from those of one’s own culture in order to facilitate interaction with people from different cultures.

While CQ is usually conceptualized and studied from the individual level of analysis, rather than societal or organizational (Elenkov and Pimentel, 2008), it has been argued that an organization such as a MNC can increase its ‘cultural capital’ by enhancing the CQ of its employees, often through ‘enriching their multicultural experiences’ (Klafehn, Banerjee, and Chiu, 2008: 327). Thus, we posit that both MNCs as a whole as well as the individuals within them have differing levels of CQ, and therefore ‘readiness to transfer’ information and knowledge across borders. The readiness to learn and transfer knowledge in a global organization rests on a threshold level of CQ possessed by a significant number of key employees within the organization.

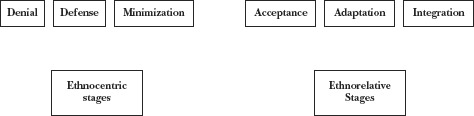

How does a MNC know whether it has a high level of readiness to transfer information and knowledge across borders and that it has accumulated sufficient ‘cultural capital’ so that intraorganizational communication across cultures can occur without major misunderstandings? Drawing on Bennett’s (1993) development model of intercultural sensitivity (DMIS), which is usually applied at the individual level, we can designate MNCs as being in either the ethnocentric or the ethnorelative stage of readiness. Within the ethnocentric level, companies and the individuals within them ‘can be seen as . . . avoiding cultural differences, either by denying its existence, by raising defenses against it, or by minimizing its importance’ (Bennett and Bennett, 2001: 14). In this stage, one’s own culture is experienced as central to reality—hence the term ‘ethnocentric.’ In contrast, people experience their own culture in the context of other cultures in the ethnorelative stage. In this stage, companies and individuals seek cultural difference, ‘either by accepting its importance, by adapting a perspective to take it into account, or by integrating the whole concept into a definition of identity’ (Bennett and Bennett, 2001: 14). CQ is closely related to intercultural sensitivity; however, the CQ concept provides greater relevance to discussing the challenge of increasing organizational learning in MNCs (for a discussion of the differences between intercultural sensitivity and CQ, see Leung and Li, 2008, 352–353).

We believe that there is a relationship among CQ, intercultural sensitivity, and readiness to transfer knowledge for global organizational learning. Communicators’ realization that they need to be aware of culture and open to knowledge regardless of its source (meta-cognitive CQ), and to question their assumptions through knowledge of their own culture and that of others (cognitive CQ), is more likely in the ethnorelative stages. At the organizational level, organizations in the ethnorelative stages are more likely to have a preponderance of key people who have both the motivation to learn about other cultural approaches to communication and to engage in the behaviors necessary to make their own ideas or others’ clear during transfer of information or learning (motivational and behavioral CQ). In contrast, based on our examination of the barriers to communication in the first part of this chapter, we would expect ethnocentric organizations and individuals to show a greater tendency to marginalize other organizational members and units, to be more prone to stereotyping, and to be less conscious and tolerant of communication style differences and less flexible in adapting to other styles. We would also expect them to be less cosmopolitan and show a greater tendency toward satisficing.

Figure 26.3 Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity

Trigger events and increased readiness to learn

We argue that both organizations and individuals are unlikely to move from the ethnocentric to the ethnorelative level of readiness without a disruption of some sort. These disruptions can be viewed as trigger events (Griffith, 1998; Osland, Bird, and Gundersen, 2008) that cause the actors to become consciously engaged and question previous schemas of interpretation. Louis and Sutton (1991) identified three types of triggers. First, switching to a conscious mode is provoked when one experiences a situation as unusual or novel—when something ‘stands out of the ordinary,’ ‘is unique,’ or when the ‘unfamiliar’ or ‘previously unknown’ is experienced. Second, switching is also provoked by discrepancy—when ‘acts are in some way frustrated,’ when there is ‘an unexpected failure,’ a ‘disruption,’ ‘a troublesome . . . situation,’ when there is a significant difference between expectations and reality. The third trigger event refers to deliberate initiatives, usually in response to an internal or external request for an increased level of conscious attention—as when people are ‘asked to think’ or ‘explicitly questioned’ (Louis and Sutton, 1991: 60).

For an organization, the first kind of situation—an unusual or novel experience—can occur when a group or unit within the global network makes a positive and unexpected contribution of information or knowledge that has an impact on organizational performance. Hewlett-Packard, for example, had to re-examine its organizational view of the capabilities of its Singaporean affiliate when presented with a clear example of the ability of the Singaporean design team to move beyond adaptation to innovation. When such questioning leads to changes in attitude about the marginality of a particular unit, as well as a re-examination of the organization’s view of its foreign operations, the trigger event moves the firm toward a more ethnorelative level of readiness.

For individuals, a similar trigger can occur when they are presented with valuable information or knowledge from an organizational member previously stereotyped as incapable of providing valuable input. A manager in the HQ of a Spanish telecommunications MNC might receive a report from its Chilean subsidiary on an innovative approach to billing customers for mobile services. Realizing that the innovation greatly enhances return on investment and is applicable world-wide could force the Spanish manager to re-examine his or her stereotypes about Chileans and other Latin American nationals, thus moving that manager toward greater ethnorelativism and openness to learning from international colleagues.

A trigger event can also be negative, a discrepancy between what is desired and what is obtained. For an organization, this could be the success of competitors’ moves in its overseas markets and a consequent fall in its own performance. The experience of Procter and Gamble in Japan in the 1970s illustrates this kind of trigger. When Procter and Gamble first acquired a medium-sized Japanese firm to manufacture its disposable diapers, it held one hundred percent of the Japanese market due to its first mover status. However, it ignored the input from the managers in its Japanese subsidiary and failed to adjust the product to fit the smaller size of Japanese babies and other considerations of Japanese mothers. It soon found that Japanese competitors flooded the market with their own disposable diapers, which led to a drop of more than seventy percent in Procter and Gamble’s market share in Japan. The company had been satisficing, basing its behavior on a superficial understanding of Japanese employees and the local context and failing to re-examine its assumptions. The reduced market share was a trigger event that led to a change in the way the company interacted with its Japanese subsidiary.

For individuals, such as the HQ-based leader of a global team, a discrepancy could include the inability to reach the goals set for the team. The leader could be facing possible negative impacts on his compensation or promotion. Examination of the hindrances to effective team performance could make the leader more aware of his tendency to discount important information or ideas because they were couched in elaborate descriptions rather than the succinct style he preferred. As a result, he might be motivated to learn more about communication style differences and attempt to reconcile his own language style with that of other team members.

Finally, an outside event such as a corporate initiative or training program can lead people to re-examine aspects of their intercultural communication. For organizations, this could include a change in corporate leadership, with a subsequent change in vision and norms. The CEO of a chemical company with a global strategy decided that international experience should be a prerequisite for promotion to senior management. The corporation’s heroes became those people who worked abroad. Repatriates were promoted and given strategic responsibilities, which made it easier to transfer their knowledge back to headquarters. The firm acquired global expertise and transformed a formerly parochial mindset to a global mindset in a relatively short time frame.

For individuals, a deliberate initiative and important disruption often involves training. Hult, Nichols, Giunipero, and Hurley (2000), for example, found in their international study of organizational learning among supply chain managers that those who had received training in understanding and using organizational learning concepts had better supply chain relationships. One could argue that the training enhanced the cosmopolitanism of these individuals, leading to greater effectiveness in intercultural communication and learning with others in the supply chain.

Discussion

In this chapter, we argue that global organizational learning is affected by the process of intercultural communication at both the individual and organizational levels. Sender-related and receiver-related factors, such as marginality, stereotypes, and CQ, influence how messages are perceived and interpreted, and they filter the exchange of ideas in a global organization. This results in both individuals and organizations having varying levels of cultural intelligence and intercultural sensitivity, which can be characterized as either ethnocentric or ethnorelative (Bennett, 1993). Trigger events—novelty, discrepancy, and deliberate initiatives (Louis and Sutton, 1991)—can help move people and firms to higher stages of cultural intelligence, ethnorelativism, and global organizational learning. Our arguments are drawn from extant theory and research, as well as experience. The following discussion delineates the managerial implications and caveats of the framework presented in this chapter, along with their benefits and costs for MNCs. We also address the questions raised by the framework that require further research.

An understanding of the intercultural communication’s impact on organizational learning yields many practical, managerial implications and caveats for global organizations. First of all, the most obvious way to diminish the effects of intercultural communication filters is through more training and emphasis on intercultural communication and the development of CQ for members of global organizations. Training and development needs to take into account the importance of intercultural sensitivity for global organizational learning. However, according to Bennett and Bennett (2001), such training should not be one-size-fits-all. To move individuals to higher levels of intercultural sensitivity, they recommend different types of training and experience for each stage.

Second, global managers should take into consideration the research findings on intergroup contact theory, which maintains that prejudice declines as a result of contact with other racial and ethnic groups (Williams, 1947; Allport, 1954). A meta-analysis of hundreds of studies concluded that contact does reduce prejudice when it is facilitated by (1) equal status; (2) group interdependent efforts toward common goals; (3) high potential for cross-group friendship; (4) positive experiences that counter negative stereotypes; and (5) authority sanction (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2000). MNCs could devote more attention and energy to these facilitating factors. Contact is needed not only between national groups, but also between different organizational cultures and different professions.

Third, while the greater heterogeneity and diversity of viewpoints and experiences inherent in MNCs can be a positive factor in organizational learning, there are also transaction costs for managers to recognize and handle. For example, stress is inherent in intercultural encounters, as evidenced in the literature on culture shock (Furnham and Bochner, 1986; Kim, 1988, 1989a) and intergroup anxiety (Barna, 1983; Gudykunst and Ting-Toomey, 1988; Stephan and Stephan, 1985). Pettigrew (2008) identified anxiety management as one of three core intercultural competencies. Learning to anticipate and deliberately manage this stress and anxiety could facilitate the transfer of knowledge.

Fourth, yet another transaction cost concerns intergroup relations. Relationships among different national or professional groups involve ‘intergroup postures’ that often cause ‘in-group loyalties’ and ‘out-group discrimination’ (Brewer and Miller, 1984; Brown and Turner, 1981). ‘We–they’ groups accentuate the perceived differences that divide them and are subject to attribution errors—inaccurate assumptions about the behavior of strangers, which are closely related to ethnocentrism and prejudice (Brewer and Miller, 1984). These tendencies are more pronounced when the groups involved have a history of dominance/subjugation or wide discrepancies in power and prestige (Kim, 1989b). More managerial attention, as well as research, could focus on the effects of marginality versus inclusion and on policies and practices that unwittingly reinforce unequal status. In MNCs, employees’ expectations and interpretations of the behavior of people and groups from other cultures are frequently inaccurate, which can affect work performance as well as organizational learning. An awareness of these transaction costs and a deliberate effort to manage them could facilitate the transfer of knowledge.

Finally, if the intercultural communication process is both transactional and irreversible, that argues for greater mindfulness—paying more attention to the way employees of global firms, as well as the firms themselves, communicate and working to ensure that communications elicit more rather than less organizational learning. Mindfulness also involves increased awareness of the ethnocentric tendencies manifested in attitudes, policies, and procedures. Furthermore, mindfulness means identifying intercultural competence knowledge in the firm and transferring and institutionalizing that knowledge throughout the organization. By doing so, MNCs can eliminate some of the filters that impede organizational learning.

In sum, more managerial and organizational emphasis and attention to training, contact, transaction costs, intergroup relations, and mindfulness could increase global organizational learning in general. However, any investment that increases the competency of global talent represents a significant cost to MNCs, and one that should not be undertaken without evidence and research findings that prove its worth. Such research, however, should not overlook the potential collateral benefits of developing intercultural communication and CQ competence. By nurturing greater meta-cognitive CQ and communication competence in a MNC’s employees, the firm is likely to increase its capacity, even in purely domestic settings, to become more aware of their own and other’s assumptions when communicating important information and knowledge. This ability to stop and reflect during interactions, both about the context of the other as well as one’s own, is a valuable skill that can lead to enhanced listening and understanding of others’ ideas. It could also be argued that increased behavioral CQ, and the greater comfort of adapting one’s behaviors to enhance communication across cultures, could also be useful when trying to interact across functional areas (say, engineers talking to marketers) or across organizational boundaries (for example, when supply chain managers in a large firm communicate with small-firm vendors). Moreover, increasing CQ generally has been found to be related to increased levels of creative performance (Leung and Chiu, 2010), which could have important implications for organizational knowledge creation in general. When MNCs have successfully managed to overcome the numerous barriers to successful intercultural communication discussed in this chapter and created greater ethnorelativism and CQ within the organization and its individual members, they may hold an advantage in organizational learning over purely domestic firms, as well as firms that lack intercultural expertise.

While the managerial implications of our framework suggest considerable benefits as well as costs, there is a clear need to substantiate the relationships we have discussed and to explore relationships the framework implies for other areas. First and foremost is to determine whether the set of intercultural communication factors chosen for discussion here is indeed the complete set of variables most relevant to global organizational learning. Second, we need to identify the relative weights each of these factors has in affecting successful transfer of knowledge in global firms. Again, without empirical research specific to this research question, it is difficult to predict which factors might be most important in explaining successful intercultural communication in global organizational learning.

A further question pertains to the relative importance of individual versus organizational actors in the intercultural communication process. Are highly ethnorelative firms in which most individual employees lag behind in CQ and ethnorelativism (which could occur through international acquisitions, for example) more or less successful than firms in which there are many ethnorelative individuals with high CQ within an overall fairly ethnocentric organization? The challenge of finding firms with these various configurations will make research into this area difficult, and require creative research methodologies. Yet the question could be an important task since the answer is likely to influence how scarce managerial resources are allocated in global firms wishing to increase their global organizational learning.

Several implications of the framework also need research to substantiate their effects. It is necessary to determine whether more intercultural training and intercultural sensitivity correlates with a higher level of both global organizational learning and firm performance, a relationship suggested by prior research (Williams, 1947; Allport, 1954). Further, while on the surface there appear to be linkages among intercultural communication competence, cultural intelligence, intercultural sensitivity, and the capacity for global organizational learning, more research is needed to test whether ethnorelative organizations are more successful at organizational learning and whether people with high levels of intercultural communication competence and cultural intelligence are more skilled at organizational learning.

In addition, the work of Bennett and Bennett (2001), upon which this framework draws, provokes several questions for organizational learning scholars. Is it possible to identify discrete stages of organizational readiness to learn globally and, if so, do we have the knowledge to move organizations to higher stages? We can readily borrow the ethnocentric and ethnorelative terms and apply them to an organization’s openness to knowledge that is created within and outside corporate HQ, similar to Perlmutter’s (1969) taxonomy. Would the identification of more narrow and discrete stages lead us to more systematic ideas for increasing organizational readiness to learn?

It is important to note that this chapter does not argue that effective intercultural communication is the most important determinant of global organizational learning. While we have argued that communication is extremely important, particularly for the transfer of tacit knowledge between individuals and groups, it may be that other mechanisms in MNCs are just as important to global organizational learning, such as information systems. Given the nature of global competition today, we believe that it is unlikely that a mechanistic system that rests on the transfer of largely archival or explicit knowledge can be a substitute for the individual and organizational communication as described in this chapter. However, we recognize that establishing the veracity of this belief is an empirical question requiring future research.

Finally, this chapter has focused on aspects of intercultural communication that filter or impede organizational learning. Scholars could take the positive perspective and examine how intercultural diversity and communication facilitates, rather than impedes organizational learning.

References

Adler, N. (2002) International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, 4th edition. Cincinnati: South-Western.

Allport, G.W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Ang, S. and Van Dyne, L. (2008) Conceptualization of cultural intelligence: Definition, distinctiveness, and nomological network. In S. Ang and L. Van Dyne (eds.) Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, pp. 3–15.

Antal, A. (2001) Expatriates’ contributions to organizational learning. Journal of General Management, 26(4): 62–83.

Apfelthaler, G. and Karmasin, M. (1998) Do you manage globally or does culture matter at all? Paper presented at the Academy of Management Conference, San Diego, CA.

Barna, L. (1983) The stress factor in intercultural relations. In D. Landis and R. Brislin (eds.) Handbook of Intercultural Training: Issues in Training Methodology. New York: Pergamon, pp. 19–49.

Barney, J. (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17: 99–120.

Barnlund, D. (1962) Toward a meaning-centered philosophy of communication. Journal of Communication, 2: 197–211.

Bartlett, C. and Ghoshal, S. (1989) Managing Across Borders. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Bartlett, C. and Ghoshal, S. (2000) Transitional Management. Boston: Irwin McGraw-Hill.

Bennett, J. (1993) Cultural Marginality: Identity Issues in Intercultural Training. In R. M. Paige (ed.) Education for the Intercultural Experience. Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, pp. 109–135.

Bennett, J. and Bennett, M. (2001) Developing intercultural sensitivity: An integrative approach to global and domestic diversity. In D. Landis, J.M. Bennett and M.J. Bennett (eds.). Handbook of intercultural training, 3rd ed, pp 147–165. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Bennett, M. (1993) Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R.M. Paige (ed.) Education for the Intercultural Experience. Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, pp. 21–71.

Bernhut, S (2001) Measuring the value of intellectual capital. Ivey Business Journal, 65(4): 16–20.

Birkinshaw, J. (2001) Making sense of knowledge management. Ivey Business Journal, 65(4): 32–36.

Bochner, S. (ed.) (1982) The Mediating Person: Bridges Between Cultures. Boston: Hall.

Brannen, M.Y. and Peterson, M. F. (2009) Merging without alienating: Interventions promoting cross-cultural organizational integration and their limitations. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(3): 468–489.

Brewer, M.B. and Miller, N. (1984) Beyond the contact hypothesis: Theoretical perspectives on desegregation. In N. Miller and M. Brewer (eds.) Groups in Contact: The Psychology of Desegregation. New York: Academic Press, pp. 281–302.

Brown, J.S. and Duguid, P. (1991) Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organization Science, 2(1): 40–57.

Brown, R. and Turner, J. (1981) Interpersonal and intergroup behavior. In J. Turner and Giles, H. (eds.) Intergroup Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 33–65.

Burgoon, J., Buller, D., and Woodall, W.G. (1996) Nonverbal Communication: The Unspoken Dialogue. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Chakrabarti, R., Gupta-Mukherjee, S. and Jayaraman, N. (2009) Mars–venus marriages: Culture and cross-border M&A. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(2): 216–236.

Christensen, D. and Rosenthal, R. (1982) Gender and nonverbal decoding skill as determinants of interpersonal expectancy effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42: 75–87.

Cohen, A.P. (1985) The Symbolic Construction of Community. London/New York: Routledge.

Cohen, W. and Levinthal, D. (1990) Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1): 128–152.

Cook, S. and Yanow, D. (1993) Culture and organizational learning. Journal of Management Inquiry, 2: 373–390.

Daft, R. and Weick, K. (1984) Toward a model of organizations as interpretation systems. Academy of Management Review, 3: 546–563.

De Geus, A. (1988) Planning as learning. Harvard Business Review, 66(2): 70–74.

Early, P. and Ang, S. (2003) Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Elenkov, D.S. and Pimental, J.R.C. (2008) Social intelligence, emotional intelligence and cultural intelligence: An integrative perspective. In S. Ang and L. Van Dyne, (eds.) Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, measurement, and applications. New York: ME Sharpe, pp. 289–305.

Fang, Y., Guo-Liang, F.J., Shige, M., and Beamish, P.W. (2010) Multinational firm knowledge, use of expatriates, and foreign subsidiary performance. Journal of Management Studies, 4(1): 27–54.

Fink, G., Meierewert S., and Rohr U. (2005) The use of repatriate knowledge in organizations. Human Resource Planning, 28(4): 30–36.

Furnham, A. and Bochner, S. (1986) Culture Shock: Psychological Reactions to Unfamiliar Environments. London: Methuen.

Garvin, D., (1993) Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 71(4): 78–92.

Gouldner, A.W. (1957) Cosmopolitans and locals: Toward an analysis of latent social roles – I. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2: 281–306.

Gouldner, A.W. (1958) Cosmopolitans and locals: Toward an analysis of latent social roles – II. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2: 444–480.

Graf, J. (1994) Views on Chinese. In Y. Bao (Ed.) Zhong Guo Ren, Ri Shou Le Shen Me Zhu Zhou? Chinese People, What Have You Been Cursed With? Taipai: Xing Guang Ban She.

Griffith, T. (1999) Technology features as triggers for sensemaking. Academy of Management Review, 24(3): 472–488.

Gudykunst, W. and Kim, Y.Y. (1997) Communicating With Strangers: An Approach to Intercultural Communication. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Gudykunst, W. and Ting-Toomey, S. with Chua, E. (1988) Culture and Interpersonal Communication. Newbury Park: Sage.

Gupta, A. and Govindarajan, V. (1991) Knowledge flows and the structure of control within multinational corporations. Academy of Management Review, 16(4): 768–792.

Hall, E.T. (1976) Beyond Culture. New York: Random House.

Hamel, G. and Prahalad, C.K. (1994) Competing for the Future. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Hannerz, U. (1996) Cosmopolitans and locals in world culture. In U. Hannerz (ed). Transnational Connections: Culture, People, Places. London: Routledge, 102–111.

Heavens, S. and Child, J. (1999) Mediating individual and organizational learning: The role of teams and trust. Paper Presented at the 1999 Organization Learning Conference, Lancaster University, Lancaster, England.

Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture’s Consequences. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Hong, Y., Morris, M., Chiu, C-Y., and Benet-Martinez, V. (2000) Multicultural minds: A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. American Psychologies, 55: 709–720.

Huber, G. (1991) Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organization Science, 2(1): 88–115.

Hult, T., Nichols, E., Giunipero, L., and Hurley, R. (2000) Global organizational learning in the supply chain: A low versus high learning study. Journal of International Marketing, 8(3): 61–83.

Inkpen, A.C. and Crossan, M. (1995) Believing is seeing: Joint ventures and organizational learning. Journal of Management Studies, 32(5): 595–618.

Inkpen, A.C. and Dinur, A. (1998) Knowledge management processes and international joint ventures. Organization Science, 9(4): 454–468.

Kamoche, K. (1996) Strategic human resource management within a resource-capability view of the firm. Journal of Management Studies, 33(2): 213–234.

Kim, D. (1993) The link between individual and organizational learning. Sloan Management Review, 35(1): 37–50.

Kim, Y. (1988) Communication and Cross-Cultural Adaptation: An Integrative Theory. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Kim, Y. (1989a) Intercultural adaptation. In M. Asante and W. Gudykunst (eds.) Handbook of International and Intercultural Communication. Newbury Park: Sage, pp. 275–299.

Kim, Y. (1989b) Explaining interethnic conflict. In J. Gittler (ed.) The Annual Review of Conflict Knowledge and Conflict Resolution, New York: Garland, pp. 101–125.

Klafehn, J., Banerjee, P.M., and Chiu, C. (2008) Navigating Cultures: The role of metacognitive cultural intelligence. In S. Ang and L. Van Dyne, (eds.) Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, measurement, and applications. New York: ME Sharpe, p. 327.

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1992) Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3: 383–397.

Langer, E. (1997) Mindfulness. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Leonard-Barton, D. (1995) Wellsprings of Knowledge. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Leung, A.K-Y. and Chiu, C-Y. (2010) Multicultural experiences, idea receptiveness, and creativity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. In press.

Leung, K. and Li, F. (2008) Social axioms and cultural intelligence: Working across cultural boundaries. Annual Review of Psychology, 58: 579–514.

Levy, O., Beechler, S., Taylor, S., and Boyacigiller, N. (2007) What we talk about when we talk about ‘Global Mindset’: Managerial cognition in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(2): 231–258.

Louis, M.R. and Sutton, R. (1991) Switching cognitive gears: From habits of mind to active thinking. Human Relations, 44: 55–76.

Lustig, M. and Koester, J. (1999) Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication Across Cultures. New York: Longman Addison-Wesley.

McCauley, C., Stitt, C.L., and Segal, M. (1980) Stereotyping: From prejudice to prediction. Psychological Bulletin, 29:195–208.

Merton, R.K. (1957). Patterns of influence: Local and cosmopolitan influentials. In R. K. Merton (ed.) Social Theory and Social Structure. Glencoe: Free Press, 368–380.

Napier, N.K. (2010). Insight: Encouraging Aha Moments for Organizational Success. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Napier, N.K. and Taylor, S. (2010) The aha experience in managing global organizations. In V. Kannan (ed.), Going Global: Implementing International Business Operations. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Nohria, N. and Ghoshal, S. (1997) The differentiated network. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organizational Science, 5(1): 14–37.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The Knowledge-Creating Company. New York: Oxford University Press.

Oddou, G., Osland, J., and Blakeney, R. (2009) Repatriating knowledge: Variables influencing the ‘Transfer’ process.’ Journal of International Business Studies, 40: 181–199.

O’Hair, D., Friedrich, G., Wiemann, J., and Wiemann, M. (1997) Competent Communication. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Osland, J. (1995) The Adventure of Working Abroad: Hero Tales From the Global Frontier. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Osland, J. and Bird, A. (2000) Beyond sophisticated stereotyping: Cultural sensemaking. Academy of Management Executive, 14(1): 65–77.

Osland, J. and Bird, A. (2001) Trigger events in cultural sensemaking. Paper presented at the Institute for Research on Intercultural Cooperation Conference, the Netherlands.

Osland, J., Bird, A., and Gundersen, A. (2008) Trigger events in intercultural sensemaking. Paper presented at the Academy of International Business Meeting, Milan, Italy.

Perlmutter, H. (1969) The tortuous evolution of the multinational corporation. Columbia Journal of World Business, January–February: 9–18.

Pettigrew, T.F. (2008) Future directions for intergroups contact theory and research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(3): 182–199.

Pettigrew, T.F. and Tropp, L.R. (2000) Does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Recent meta-analytic findings. In S. Oskamp (Ed.) Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination. Mahwah: Erlbaum: 93–113.

Reiche, B.S., Harzing, A., Kraimer, M.L., Reus, T.H., and Lamont, B.T. (2009) The Double-edged sword of cultural distance in international acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(8): 1298–1314.

Reus, T.H. and Lamont, B.T. (2009) The double-edged sword of cultural distance in international acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(8): 1298–1314.

Senge, P. (1990) The Fifth Discipline. London: Century.

Simon, H.A. (1976) Administrative Behavior. New York: Free Press.

Stephan, W. and Stephan, C. (1985) Intergroup anxiety. Journal of Social Issues, 41(3): 157–175.

Stonequist, E. (1932) The Marginal Man: A Study in the Subjective Aspect of Cultural Conflict. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Thich, N.H. (1991) Peace is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life. New York: Bantam Books.

Ting-Toomey, S. (1999) Communicating Across Cultures. New York: Guilford.

Tushman, M. and O’Reilly III, C. (1997) Winning Through Innovation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Williams, R.M., Jr. (1947) The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions. New York, NY: Social Science Research Council.

Zander, U. and Zander, L. (2010) Opening the grey box: Social communities, knowledge and culture in acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 41: 27–37.

1There are other communication differences related to culture, such as monochronic versus polychronic time schedules and instrumental versus affective styles, but they appear to have less potential direct impact on organizational learning.