Chapter 3. Your Audience

Your portfolio is an expression of who you are. But even the unique “you” changes according to your mood and situation. Kicking back with friends sparks a different state of mind than visiting your family. It should. You’re relating to people whose assumptions, goals, and values are probably galaxies apart. However, unless you’re a chameleon, you don’t become someone new with each group. You adapt your style to make the people you’re with more comfortable with you.

Creating a portfolio that speaks effectively to prospective clients or employers might require similar adjustments. But when you are with different groups, you have the benefit of knowing their expectations already. You’ve had years to learn the unspoken code of conduct that each situation requires. That’s probably not true of your portfolio audience. To get your share of the current opportunities, you need to be aware of what your market desires, and show that awareness explicitly with your portfolio.

With self-examination fresh in your mind, this chapter will point you in the direction of tools that will help you sharpen your marketplace savvy. We’ll move from figuring out what topics you need to research, through good places to do your researching, to some practical tips on how to conduct fruitful market research. By the end of the chapter, you’ll be well on your way to knowing who your target is and what they’ll want to see in your portfolio.

Why do research?

Part of the allure of digital portfolios is how fluid they are. Plan wisely, and you can quickly roll out a series of portfolios, each tailored to a single market, culture, or geographical area. However, you need to know a lot about each audience to speak effectively to it. Knowledge is key to chasing the right work, media, and approach.

Wouldn’t it be nice if the people you’d like to work with would just tell you what they want? Actually, they do. They publicize new campaigns and give interviews about their strategic partners. They give talks at clubs and offer their opinions at student critiques. They put up websites with client lists and project samples that tell you the type of work they do and what types of firms they’re pleased to do it for. Sometimes they even provide case studies that tell you all about their working process. This abundance of information tells an astute observer volumes about their philosophy, aesthetics, and company culture. You find this wealth of information through research.

Armed with solid research, you don’t have to design your portfolio and hope you’ve made the right choices. An illustrator who has researched his targets’ styles and clientele can showcase examples of appropriate work online. A designer can send an individually created PDF that shows her knowledge of a firm’s client base or working process.

The word research makes some visual people twitch. Don’t let it. You’re just poking around for information, something you probably do for personal projects or just plain curiosity without giving it a second thought. The only difference here is that you’ll be aware of what you’re doing and have a long-range goal in mind.

What should you research?

Your research will be most effective if you move from the general to the specific. The further along you are in your career, the finer you might winnow the field. If you are already very focused and aware of your possible market, you might simply research individual prospects.

Depending on why you are creating a portfolio, you may pause at, stop on, or skip directly to any of four progressively more detailed research stages.

1. Do basic market research.

Savvy creative professionals always ask, “Who’s your customer?” of their clients. Design and advertising are driven by market forces. Each individual market needs to be approached in a unique way. We all know—or we should—that it’s hard to develop a good logo, design effective communication, or create a killer game if you haven’t a clue about who you need to sell to, speak to, or impress.

We may complain about our clients’ myopia, but we can be guilty of the same career crime. Although you can do every type of work for anyone, you are probably better at some types of projects than others. The end result is more satisfying and better produced, and you’re proud to show it. Why not make yourself more attractive to people who can offer you such a project?

When you aren’t consistently getting the work that you would like, you either have to look closely at yourself (as we did in Chapter 2, “Assessment and Adaptation”) or your working environment. If you’re not sure how to define your audience or what type of audience matches you best, the “Market assessment” sidebar provides a list to spark your thinking.

Which of these items is most important to you? Priorities matter because your ideal situation may not exist. Refer to your self-assessment in Chapter 2 to help you prioritize and narrow your focus.

You might not be sure of how some factors play out—company size, for example. A large corporation may put you to work on one mammoth project, giving you an overview of process and production. Or if you’re looking for clientele, you may have prior experience with certain demographics. Should you look for a client that sells to that market? If you’re not sure how some of these topics affect your job or client search, you’ve found a good subject to research.

For example, let’s say that you want a better idea of how company size is likely to impact your project opportunities. You could move forward by selecting a small group of companies that do your type of work—half large (advertising companies or design firms listing more than one branch) and half small (firms with a single principal’s name or with a creative or unusual identity are often small, personal concerns). Go to their websites and poke around to see how you respond to the type of projects on view, the type of clients (big corporate names or small local companies), and the design of the website itself. A large firm will only show work from a small client if the work represents their most creative effort—a good gauge of their creative range. A small firm may display fairly pedestrian projects if they’ve been done for a prestigious name—a good measure of their long-term growth aspirations.

2. Find your target audience category.

After you have created a basic definition of your portfolio’s target audience, look for general data about this target. Some typical questions to answer might be:

• Is my target realistic? Are there companies that do exactly what I’m looking for, or should I be more general?

• How many companies fit my target? Can I narrow it down?

• How many companies are local? Does the geography matter to me?

In doing a general category search, you should come up with several pages of possible company targets. If you’re in the triple digits, you need to be more selective. If you have only ten options, you’ve narrowed your options too far and too fast.

3. Select specific companies.

Now you’re homing in on companies that exemplify the type of work you’d like to do.

You may have found these companies initially by exploring links from the general search or by developing a separate list from directories maintained by professional organizations. (See Appendix A, “Resources.”) These companies will become the target audience against which you will “test” your portfolio concepts. You’ll ask more specific questions about this group:

• What do the companies I’ve short-listed have in common?

• What do they have to say about their process or client relationships?

• What types of clients do they specialize in?

• What is the range of work they do?

The more these companies have in common, the easier it will be to create a digital portfolio that will be appropriate to the group, yet feel individually crafted when you approach each one. Understanding the visual language and work culture of the companies you admire will make it easier to winnow your existing work and develop ideas for your presentation.

If you are in possession of this information, you can use it to answer a broad range of vexing questions about your portfolio format, content, and design. Here are some examples of questions that you can find answers to through networking, periodicals, school contacts, websites, or other research sources:

• Should I put that group of photographs in my graphic design site?

• Will they appreciate my sense of humor?

• Which illustrations are likely to get me more book work?

• Will they be put off by the ad campaign work?

• How much new media work should I bring? How much print work?

4. Research the best way to present yourself.

Defining your audience and determining their basic category information should always take place before you begin your portfolio. They may be all you need. But in some situations, you want to impress an audience of few—or one. If you’re well-organized (see Chapter 5, “Organizing Your Work”), you may be able to quickly compile a version of your portfolio for one special company.

Search questions to answer about a specific firm:

• Are they busy? Are they hiring?

• What is their aesthetic? Do I like it? Would I be proud to work with them?

• What’s their philosophy or way of working with clients? Could I work within it?

• Does their website or other official address tell you how they like to be approached? Email? Letter? Phone?

• Who are their decision makers? What does their personal work look like?

• What are they like to work for?

You may wonder why you need to ask these questions. You’re applying for a job, not marrying the company! Yes and no. If you’re hired, you’ll probably spend more time at the office than you do with your significant other. You need to know that those hours will be well-spent and that the projects you take on will enhance your portfolio. Also, you should consider the other side. If you are hired, but it’s not a good fit, you might not stay hired for long. You could have used that time to find a more compatible situation.

For a full-throttle search on one company, word-of-mouth information from personal and local contacts is the most precious and useful source, particularly to find out if the company offers a solid work opportunity.

Search tools

No matter the scope of your search, you’ll be using tools that you probably take for granted: personal networks, periodicals, and the Internet, particularly Google.

Personal contacts

A personal network is your best resource. Do you know anyone who has the kind of job you want? If they are secure in their position, they might tell you what people at their firm say about the portfolios that get passed around. Creative professionals in related areas can be excellent contacts because they talk to the same people you want to—but about different work. They might give you a contact name in the organization who would be willing to look at your current material and give you direct feedback on it. (See Chapter 13, “Presenting Your Portfolio.”) Other surprisingly good contacts are representatives of supplier companies, such as printers. They can often tell you who in your city is busy and might be ready to hire new talent.

WWW.SEGD.ORG

The Society for Environmental Graphic Design is only one of many professional societies that offer networking opportunities. Each active local chapter should offer special meet-and-greet events, ranging from workshops and seminars to cocktail parties. Larger chapters may offer lectures, special events, and local job listings.

If there is a professional association in your field, join it. Most large national associations, like the AIGA and the IDSA (Industrial Designers Society of America) have regional chapters with contact information listed on the associations’ main websites. (You’ll find a list of professional associations and their websites in Appendix A.) Very active chapters will have their own websites, brimming with useful information about the local scene. Go to the meetings, and take advantage of any career events they sponsor. If you are new to your profession, volunteer your time, particularly for events and projects that will give you the opportunity to work with people at different levels of experience. People are more likely to go out of their way to answer questions for someone they’ve met (or for the friend of a friend).

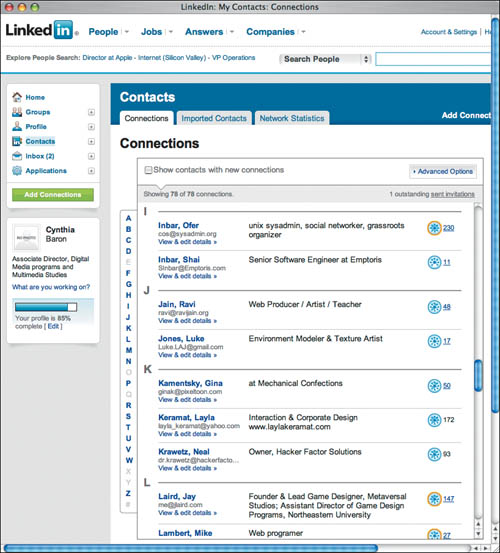

WWW.LINKEDIN.COM

This site is a professional social networking space with an infinite Rolodex. A LinkedIn profile requires minimal maintenance, but pays great dividends in building both a network of contacts and a library of recommendations.

Social networking

Although it’s not the same as a face-to-face encounter, a social network can often be a better way to learn about job-related opportunities than most personal encounters. It can be hard to ask an acquaintance at a cocktail party for an introduction to one of their coworkers. It’s comparatively easy to put yourself out there in a site explicitly devoted to making friends and building your business network.

You probably belong to not just one, but several social networking sites already. All of them are valuable resources, because the more people you know and who know you, the better chance you have of meeting your goals. That being said, social networks with a focus are less distracting. Facebook may be a dominant network, and it’s a great way to stay in touch with friends, but it has yet to prove itself as a professional destination. Although you can post artwork, other addresses may be better for a small portfolio. Facebook’s superficial, short-form communications don’t always lend themselves to work-related topics.

One excellent option is LinkedIn. Explicitly created for professional networking, it relies on the “six degrees of separation” concept for careers. You create a profile that can easily take the place of an online résumé, then invite people to become part of your network of connections. Once you connect with a person, you can see people in their network, and potentially add them to yours.

Aother option is to seek out professional networks that were created specifically for you and others like you. One of the very best for creatives is The Behance Network (www.behance.net). It’s an all-purpose destination for anyone in the creative industries, complete with job listings, a gallery of portfolios, and its own e-zine.

Forums and directories

You can also learn a tremendous amount by visiting online forums (see Appendix A). People are there to discuss professional practice and are willing to offer advice and a reality check. One excellent source for lists of forums and discussion groups is Yahoo (groups.yahoo.com). It is intelligently organized, and topics are easy to find. General career websites like The Vault (www.vault.com) can be helpful as well if you are hoping to work for a large company with a creative services or marketing communications department. The message boards on these sites are full of people who are already working at or are former employees of the company.

Most professional organizations have statistics and surveys about your profession, from pricing structures to presentation standards, often broken down by geography or industry. While some of this material is published for general use, other parts of it might be for members only. Contact information for a selection of relevant organizations can be found in Appendix A.

WWW.GRAPHICDESIGNFORUM.COM

The best online forums are a one-stop resource for everything from technical questions to portfolio critiques.

WWW.RISDBOSTON.ORG

RISDBoston is a very active local chapter of Rhode Island School of Design alumni that lists local firms with a special interest in RISD graduates. Firms with alumni contacts are starred, and alumni are listed with their graduation year.

Schools, universities, and alumni associations

Did you graduate from an art school or from a university with a large department or school in your specialty? If so, you could have an invaluable resource at hand. A specialized school might offer career counseling and even placement services for alums. As a service to their students, schools often offer great career links. Even if they don’t, they’re usually well-connected with firms in their local area and committed to offering useful information that can be exactly what you need for your target audience search.

Some art and design schools have an intricate network of alumni associations in major cities worldwide. Local alumni clubs have lists of companies with established professionals who are willing to offer informational interviews—or even a shot at real jobs—to other alums. They can help you match your skills and interests with companies whose style and philosophy are compatible with your own. Even nongraduates can sometimes find these organizations helpful. You can use their lists of prestigious firms and contact names in a category search or to find possible targets in a geographical area that interests you.

Searching with Google

Unquestionably, the Internet is the single best tool for capturing information. There’s almost nothing you can’t find out about potential clients or employees—in general or in specific—by using Internet resources. And Google is the tool of choice for searching it.

Simple search

Googling a specific company, sometimes with some additional criteria, will get you their website, as well as any other sites they maintain (like a separate blog), as well as mentions of them and their principals in articles. Phrases such as “working for (target company here)” or (target company) and “resume” will get you job listings and contacts.

Remember to make bookmarks so you can return to them later and organize your search results into categories, like “job directories” and “art schools.” Half of the battle in research is knowing where you put things. If you have to reconstruct your sources every time you have a problem to solve, the process will take much longer.

Googling by location

Imagine that you’re a designer who has recently relocated to Montreal. You’re looking for design firms that do branding and are within easy driving distance of your new home.

If you go to Google and type in “branding agency design” you may be surprised to discover that Google knows a lot more about you than you think. The list will probably be specific to your home area. Very close to the top of the list, you’ll probably find a search result with a map that keys some of the companies that tag those words on their home page. The initial list is short, but if you select the “More results” option at the bottom of the listing snippet, you’ll find every firm that fits your criteria in the metropolitan area.

If Google brings up results in your former home location, just click the “Change location” link to input your new city.

Google and directories

Sometimes what you need is a list of lists. If you type in your creative area and the word directory as a search, you’ll locate a mountain of already-researched associations, job listings, and fellow travelers in your profession. An excellent resource that is indicative of what you can find this way is BusinessWeek affiliate Core 77 (www.designdirectory.com), which is a well-organized database of professionals and firms in all the major design fields. (See Appendix A for a list of some good directories to use as starting points.)

One gem hidden deep inside Google’s many tools is Google Directory (directory.google.com). Select Arts, and a list of relevant categories appears. Are you an illustrator or web designer? Select the Design category and drill through the options.

Googling with advanced search

Even with Google’s shortcuts and intelligence, it can offer too much information. Sometimes, you need to design a search criteria that will find information that isn’t readily available. Clicking the Advanced Search option to the right of the Search button will give you the opportunity to specify words that must factor into the results as well as eliminating those that don’t sound right for you. In our hypothetical search below, we’ve strategically slimmed down the results to only 129. That’s a reasonable number to explore.

Turn to Google’s advanced search function if your first easy search turns out to be too general. This search for a company that has won awards for branding in Canada turns up a million results. The advanced search applies several strategies. By putting quotes around design agency it requires these two words to appear together as a phrase. By adding optional words, in this case two preferred locations in Canada, these locations must be mentioned in order for a site to appear. Last, by specifying words that should not be part of the site, it eliminates the location of Vancouver (too far away) and subtracts any school websites.

Hit the books

Creative professionals frequently pore through Graphis, Communication Arts, and other magazines for inspiration. These publications are also useful for research. Look for work you admire and see if the companies or studios who’ve done the work fit your general audience description.

You can also use these books to create a web search, a particularly fine strategy if the companies you love don’t happen to be anywhere near where you live. Go to their websites and look at the source HTML code, as shown below. There should be a descriptive list of words inside tags. These tags, and the words inside them, are called meta tags or description tags. Use these words for your local area searches, and you should find companies that describe themselves the same way and, hopefully, do the same type of work.

Meta tags are used by web search engines to find sites that meet your criteria. Someone at the company has deliberately chosen these words to make their site come up frequently in web searches.

When are you done?

One of the dubious delights of research is that it is never completely finished. There are always little tidbits of information that can teach you more about your target audience or change your focus. Once your portfolio is underway, it’s a good idea to revisit individual websites and check for recently posted articles.

In the meantime, you should have developed a feel for the market you want to enter or the companies you want to entice. Looking at their work has helped you judge what parts of your own work might be most effective. Reading about their philosophy and comparing it to their client lists will tell you whether you should be conservative or try for a tour de force. If you’ve been researching potential clients, you’ll know who they’ve used previously, why they continued to use them (or dumped them), and whether they might find your approach compatible.

In short, you’ll know your subjects well enough to have built a little target audience construct in your head. Based on your self-assessment from Chapter 1, do your current skills and work fit that picture? If they don’t, you’ll need to determine the changes you need to make to bring your portfolio into the right ballpark. If they do, you can steam confidently ahead.

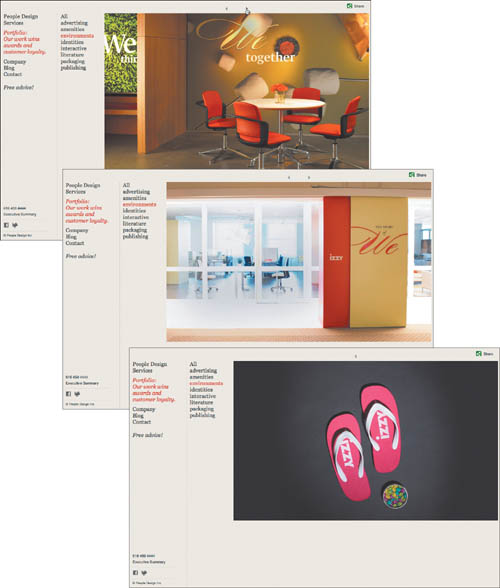

Portfolio highlight: People Design | Know your market

As anyone who is old enough to remember New Coke knows, it can be a very dangerous thing to mess with an established brand. So, when partners Kevin Budelmann and Yang Kim decided to replace BBK Design, their award-winning design studio, with a refocused consultancy—People Design—they knew they were taking a radical step. After years of targeting marketing departments, they selected a new audience: corporate leaders who were looking for an innovative, integrated approach to their users’ experience.

To the right of the main navigation is a column of short titles, encouraging the visitor to jump directly to a topic of interest.

Because the main menu persists, it’s easy to jump back after reading one of the essays.

At the bottom of the page, discreetly nestled under the logo, are a downloadable executive summary and contact options.

The People Design website needed to do some heavy lifting in order to reassure existing customers while convincing a new audience that they could deliver on an ambitious agenda. They decided to reorganize and redesign their existing portfolio to make it equally easy for their audience to see their work across multiple categories for single clients as well as multiple clients within product categories. And, most importantly, to emphasize visual inspiration rather than case study analysis.

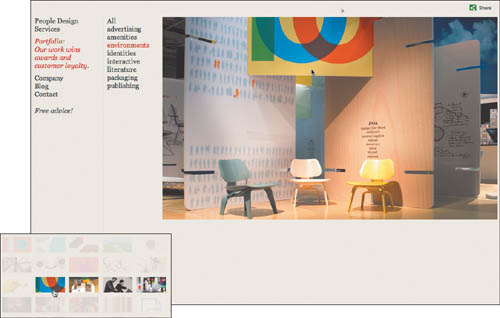

Select Portfolio from the main navigation, and a grid of thumbnail images appears, accompanied by a submenu of portfolio categories.

Select a category from the submenu, and the topic color changes to red to remind you of what you selected. Selecting All returns all thumbnails to active mode.

The items in the portfolio grid that are not part of the selected category fade and are no longer active. Clicking another category brings up a different collection of thumbnails.

Navigation and architecture

The site structure is extremely compact. There are no Flash intros, or content prequels. Beginning with a clear statement of identity and purpose on the splash page, the main site sections appear in a standard vertical list. Each main header is a portal to its own home page, where all of the section’s content displays. This strategy makes for a very shallow site that limits unnecessary mouse clicks.

The portfolio page is a surprise. Most portfolios, intentionally or by default, directly translate the organization of a physical portfolio to an interactive space. This often takes the form of a menu organized by category, client, or project list.

Selecting an active thumbnail opens the slideshow window. If you have chosen a subset category, only the images belonging to the subset join the slideshow.

Click on the first image in the slideshow and you return to the portfolio grid.

People Design rethinks this portfolio metaphor, in keeping with their belief that a prospective client is most interested in inspiration. The portfolio, which is accessed from one of the main menu options, is a wall of thumbnail images—snippets of interesting texture or details from the image they represent. Although it is possible to experience the portfolio by selecting a category from the portfolio menu list, this option is only one of many. You might also click any image to launch a simple slideshow that browses sequentially through the entire collection, or you could just randomly click on individual thumbnails.

Click on the forward arrow above the image and the sequence loads. From that point, you can either use the arrows to click back and forth through each sequential image, or click anywhere on the large image to move forward.

Interactive projects inside the portfolio play as encapsulated movies from a Vimeo feed, allowing you to see the navigation in action, or to see more than one page of the client site.

No matter how the viewer chooses to experience the samples, it requires very little user action to tell the portfolio story, and no clicks away from either the menu or the image grid.

Content

People Design has jettisoned the case study approach to its portfolio. Instead, they have looked carefully at what a prospective client really wants to know about them. The portfolio doesn’t burden the viewer with content that may not be relevant to their needs, or require a shift from visual to text processing. It provides a selection of media projects that emphasize the broad range of challenges the company has tackled successfully and gives the viewer the freedom to browse casually, or pursue a specific theme.

Instead of case studies, People Design emphasizes team, personality, and process—the common threads for all their work. Prospective clients can visit the Services section for a short presentation of People Design’s working framework or visit the Company link to learn more about them as a potential design partner. Some might even decide to read the Blog, which is a prime destination for people—other designers, company fans, or aspiring employees—who want to stay on top of their thinking as design leaders. In all cases the nature of the content is clearly defined and well-categorized. The visitor can clearly engage in whatever aspect of the site most interests them without distractions or false moves.

Future plans

Portfolio sites are always in flux, and you learn from what works. People Design is constantly tweaking the back end to improve content organization and flow. As Budelmann says, “We put a lot of thought into this site, trying to marry print/analog paradigms with best practices and innovative thinking online. The structure is intentionally flexible and we intend for it to grow.” By the time this case study is in print, the site features will have been expanded to personalize the experience for existing clients and to incorporate elements from social media networks (like Twitter) directly into the site.