Chapter 1. Assessment and Adaptation

You’d be surprised at what an experienced reviewer can assume about you from looking at your portfolio. Some reviewers may react negatively to choices you’ve made and pass you by, even if you’d do a great job for them. You can neutralize your portfolio to prevent that, avoiding examples of chance-taking work. This decision has its own pitfalls. Many art directors use a portfolio to get a sense of who you are. If your portfolio is too dry, they’ll worry that they won’t enjoy working with you.

It’s in your best interest, then, to evaluate yourself and your work before it’s done for you. Self-evaluation is tough. Although you use some of the same skills you would if you were developing a concept for a client, applying them is much harder when the product is yourself. You carry around blind spots that might make you emphasize the wrong things in your portfolio or pursue work in an area that isn’t your best. What are your strengths? What will you need to overcome? Do you have the talents that your target audience wants? Where do you need to adapt to the market? Answer these questions and you have a focus that will shape your subsequent portfolio decisions.

Soul-searching

Even if you aren’t naturally introspective, don’t skip this step. In fact, it’s probably most important if you tend to be impatient with self-examination. You’re in a profession where personality matters because it is so frequently reflected in how you approach concepts and ideas. The self-assessment checklist that follows will help you to think clearly about your abilities, needs, and goals. Not only will this help you develop an appropriate portfolio, but it will prepare you to talk effectively about yourself and your work in an interview.

Self-assessments are subjective, not scientific. You’ll find this one most useful if you collate the results of each topic and use them at major decision points in your portfolio development: determining your target market (Chapter 3, “Your Audience”), preparing your résumé, briefs, and other text (Chapter 8, “Creating Written Content”), and making the all-important concept decisions (Chapter 9, “Structure and Concept”). It is less important to rack up points than it is to have the right points.

In general, solid experience is more valuable than training and can balance some gaps in formal education. Without experience, you should be more flexible in your goals and prioritize your values. In a down economy, there’s always pressure to be employed first and fulfilled second. But compromises are out there. Consider positions that offer the opportunity to learn from experienced professionals, even if those positions pay less than those that reward your technical skills. Or use the pay from a production job to finally get the formal education that will open the door to new options later.

Values should overlay your goals. The more selective your values, the less likely it is that you will find happiness in a large corporation, and the harder it may be for you to make a major creative change. If you have a reasonable head for detail, you might be happier as a freelancer than as an employee.

Personality is a critical component and can, in the highly subjective world of the arts, move you closer to your goals even if some of your preparation is spotty. If you’ve chosen one set of words to describe your work and a completely different set to describe your “true” style, you need to reexamine your answers to the other sections and prepare for many hard choices as you mold your portfolio.

Self-assessment checklist

These questions have no right or wrong answers. They also have nothing to do with how talented you are. (There’s no way to judge that with a checklist.)

No one has to see these results but you, so be completely honest. Refer to this assessment at many points along your portfolio process: as a reality check against your target audience, as you decide what projects to include in the portfolio, and as you choose the type of portfolio most likely to help you reach your goals.

Strengths and weaknesses

1. Educational experience in my profession:

![]() Self-taught

Self-taught

![]() Non-credit classes

Non-credit classes

![]() Certificate or associate’s degree

Certificate or associate’s degree

![]() Bachelor’s degree

Bachelor’s degree

![]() Advanced degree

Advanced degree

2. Educational experience in a related or supporting profession (check all that fit):

![]() 2D art fundamentals

2D art fundamentals

![]() 3D modeling or rendering

3D modeling or rendering

![]() Environmental design

Environmental design

![]() Video and/or animation

Video and/or animation

![]() User-interface and/or interaction

User-interface and/or interaction

![]() Marketing

Marketing

![]() Photography

Photography

![]() Graphic design

Graphic design

![]() Industrial or product design

Industrial or product design

![]() Typography

Typography

![]() Scripting or programming

Scripting or programming

![]() Writing

Writing

3. Work experience within a related or supporting profession (check all that fit):

![]() 2D art and illustration

2D art and illustration

![]() 3D design: modeling or rendering

3D design: modeling or rendering

![]() Marketing and/or advertising

Marketing and/or advertising

![]() Graphic design: print

Graphic design: print

![]() Graphic design: identity and branding

Graphic design: identity and branding

![]() Graphic design: packaging

Graphic design: packaging

![]() Photography or image editing

Photography or image editing

![]() Video and/or animation

Video and/or animation

![]() User-interface and/or interaction

User-interface and/or interaction

![]() Scripting or programming

Scripting or programming

![]() Game design

Game design

![]() Journalism, editorial

Journalism, editorial

4. I have software training in (check all that fit):

![]() Photoshop and related imaging software (Fireworks, etc.)

Photoshop and related imaging software (Fireworks, etc.)

![]() 2D illustration and print design software (Illustrator, InDesign, etc.)

2D illustration and print design software (Illustrator, InDesign, etc.)

![]() Production software (Acrobat, color-proofing software, etc.)

Production software (Acrobat, color-proofing software, etc.)

![]() Flash or other animation software

Flash or other animation software

![]() Web programming languages like ActionScript or JavaScript

Web programming languages like ActionScript or JavaScript

![]() Web design coding and software (HTML, CSS, XML, Dreamweaver, etc.)

Web design coding and software (HTML, CSS, XML, Dreamweaver, etc.)

![]() Rendering or CAD programs (AutoCad, Form-Z, etc.)

Rendering or CAD programs (AutoCad, Form-Z, etc.)

![]() 3D or animation programs (Maya, 3ds Max, etc.)

3D or animation programs (Maya, 3ds Max, etc.)

![]() Video editing software (After Effects, Final Cut Pro, etc.)

Video editing software (After Effects, Final Cut Pro, etc.)

![]() I have no software training.

I have no software training.

5. Exclusive of school, I have been working in my chosen profession for:

![]() < 1 year

< 1 year

![]() 1–3 years

1–3 years

![]() 3–7 years

3–7 years

![]() 7–10 years

7–10 years

![]() 10+ years

10+ years

(Don’t count time spent unemployed if you didn’t freelance at least part-time.)

6. Rate your skills (not your raw talent) in your primary area:

![]() A master of my craft

A master of my craft

![]() Have lots to teach others

Have lots to teach others

![]() Better than most

Better than most

![]() Better than average

Better than average

![]() About average

About average

![]() Still learning

Still learning

Goals

7. Why are you making a digital portfolio? Check all that apply:

![]() Creative outlet

Creative outlet

![]() Required for school

Required for school

![]() About to graduate

About to graduate

![]() Unemployed, looking for a job

Unemployed, looking for a job

![]() Employed, looking for a job

Employed, looking for a job

![]() Client marketing tool

Client marketing tool

![]() Professional project record

Professional project record

![]() Need the technical practice

Need the technical practice

8. If your portfolio needs are job-related, check the statements that apply to you:

![]() I’ll take any job I can get in my profession.

I’ll take any job I can get in my profession.

![]() I want a job similar to one I have or had.

I want a job similar to one I have or had.

![]() I want a job at a higher responsibility level.

I want a job at a higher responsibility level.

![]() I want to do specialized work in my profession. Name the area:

I want to do specialized work in my profession. Name the area:

_________________________________________________________

![]() My previous jobs were unfulfilling. I want to do something different.

My previous jobs were unfulfilling. I want to do something different.

![]() What I haven’t liked about my jobs:

What I haven’t liked about my jobs:

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

![]() I want/need to change my creative profession.

I want/need to change my creative profession.

![]() My current profession is ___________________________ and I want to be a ______________________ (job title).

My current profession is ___________________________ and I want to be a ______________________ (job title).

9. If your portfolio needs are client-related, check the statements that apply to you:

![]() I am happy with the type of clients I currently have but need more work.

I am happy with the type of clients I currently have but need more work.

![]() I want to specialize in specific industries or types of work. Name the area:

I want to specialize in specific industries or types of work. Name the area:

_________________________________________________________

![]() I want to add to or change what I’ve specialized in. I currently specialize in ________________________ (name of area) and want to specialize in ________________________ (name of area).

I want to add to or change what I’ve specialized in. I currently specialize in ________________________ (name of area) and want to specialize in ________________________ (name of area).

Values

10. How do you like to work?

![]() Alone

Alone

![]() Collaboration or partnership

Collaboration or partnership

![]() As a team member

As a team member

![]() Doesn’t matter

Doesn’t matter

11. What’s your preferred working environment?

![]() I can work anywhere.

I can work anywhere.

![]() I need a private space.

I need a private space.

![]() I like to have other people around.

I like to have other people around.

![]() My colleagues must be friends.

My colleagues must be friends.

12. Select the statement that fits you best:

![]() I will take jobs from any paying client.

I will take jobs from any paying client.

![]() I won’t accept some types of clients or client work.

I won’t accept some types of clients or client work.

![]() In specific, I won’t accept this type of work: _____________________

In specific, I won’t accept this type of work: _____________________

_________________________________________________________

Personality

13. Check up to five of these words that best describe the work you’ve done:

![]() Personal

Personal

![]() Sexy

Sexy

![]() Serious

Serious

![]() Clever

Clever

![]() Intuitive

Intuitive

![]() Elegant

Elegant

![]() Confident

Confident

![]() Trendy

Trendy

![]() Funny

Funny

![]() Sensitive

Sensitive

![]() Complex

Complex

![]() Analytical

Analytical

![]() Crisp

Crisp

![]() Challenging

Challenging

![]() Thoughtful

Thoughtful

![]() Playful

Playful

![]() Intellectual

Intellectual

![]() Detailed

Detailed

![]() Organized

Organized

![]() Boring

Boring

![]() Issues-oriented

Issues-oriented

![]() Brash

Brash

![]() Sarcastic

Sarcastic

![]() Emotional

Emotional

![]() Impulsive

Impulsive

![]() Structured

Structured

![]() Cooperative

Cooperative

You’ve chosen words that currently describe your work. If you feel that the words you’ve chosen don’t reflect the style or approach you’d like your work to have, select some words from the list that do so:

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

WWW.FISTIK.COM

Some 3D animators are very adept on the computer but have problems story-boarding or making detailed sketches with traditional media. Cemre Ozkurt’s web portfolio has ample examples of his ability to think and draw creatively both on and off the computer screen.

Strengths and weaknesses

You have both, and you should know them well. Technical strengths and weaknesses are the most obvious and the easiest to assess. Some employers are on the prowl for specifics, like computer proficiency or knowledge of printing processes. They need evidence that you can handle their work.

Knowledge is tougher to assess because it can be hard to recognize what you don’t know. That’s why the checklist differentiates between formal professional education and courses that simply cover the how-tos of an application. For example, a professional degree is most necessary in the design fields. If you don’t have a degree, you’ll need to balance that lack with more years of high-quality work experience. Software training is most useful in areas with very high learning curves, like 3D, while sheer skill is most important for artists, photographers, and animators.

WWW.CLOUDRAKER.COM

Click Montreal and the mounted longhorn head comes down, along with a label. Click Amsterdam and the Sherpa character moves right to make room for the mounted reindeer. This interactive animation sequence has a lot of technology under the hood. How long might it take you to duplicate this combination of animation and programming? The answer to that question can mark the difference between qualifying for an interface design position and a most unpleasant learning experience.

Self-confidence is important, but it should be based on reality. Without real experience or formal education or training, you may not be qualified to tackle the challenging or sophisticated projects you crave. Or you might find that you’re hired for a job that becomes a nightmare because you’re behind the learning curve.

If you don’t have enough training or experience to land the position you want, don’t lose hope. Address the problem by focusing on a short-term goal—creating a portfolio that plays to your current strengths—while you upscale your skills and knowledge.

Goals

Begin a portfolio without understanding why you’re making one, and it will fall prey to one of the classic portfolio concept errors (see the section, “What a portfolio is not”). A portfolio begun in ignorance or pure desperation telegraphs its weaknesses.

It’s not enough to say, “I need a job!” A job is a financial requirement, not a goal. You could fix plumbing or drive a cab. It is equally insufficient to say, “I need clients!” You can do work for clients who aren’t a perfect fit, but it would be a mistake to create a portfolio that will only bring in the wrong type of work for you. Never lose sight of the fact that you’re in this because it’s work you want to do—it is satisfying and it matters.

Set two goals now: your long-term career and your short-term job. The first should rule your portfolio’s presentation format and the type of work you show. The second will determine the specific projects you include and how you customize the portfolio for individual needs. Perhaps you want to specialize in packaging and identity projects. Short-term, you need a job that gets you a step closer to that goal. That might mean creating a portfolio to interest companies that specialize in print, rather than those that specialize in interactive design.

What if you have started out in one direction, and your goal is to strike out in a new one? If you have been designing CD covers and want to design for the medical industry, you will be competing against people who are already “experts” in a demanding and complex field. When you make a risky and demanding change, you may have to construct your portfolio from scratch. Be sure that there is a fit between how you feel about risk and the goal you choose.

Values

Values determine what makes you comfortable and happy. You shouldn’t knowingly target situations that you’ll dislike unless the wolf is scratching at the door. Even when things are tough, it might be better to take a series of freelance or temp jobs than to accept a full-time position that you know is completely wrong for you. Long term, if you subvert your taste and instincts to land a client or a job, your portfolio becomes a collection of compromises, and your self-confidence can ebb. Eventually, you’ve done a lot of work you don’t want to show, and you will have to work extra hard to counteract it in your presentation.

That being said, everyone makes work compromises at some point in their careers. Some are worth making. Only you can determine where you draw the line, but you should at least know where the line is, and whether it is a realistic limitation. You can’t survive without a certain amount of flexibility. Not every project is groundbreaking and edgy, and you can learn a lot from projects that make you think along unfamiliar lines.

WWW.SKEVINLONGO.COM

In a vast wasteland of predictable site design, a portfolio like S. Kevin Longo’s is a refreshing taste of his distinctive design personality. It demonstrates that he can take a fresh look at projects and might be a fun creative voice on a team.

Personality

Does your work display a unique flavor? This question is subjective but goes to the heart of your portfolio. If your profession is style-based, your portfolio and all the work within it should express a personality. The words you’ve chosen in the self-assessment profile should describe the flavor of your work. If you create images (illustrations, photographs, and so on) the words you’ve chosen should be strong, related descriptors. Impulsive, clever, and sarcastic might work together. Intuitive, trendy, and complex might be too far apart to provide a focused sense of who you are.

In professions, like graphic design, that emphasize variety, your personality should be less obvious in a client project. A designer works for a range of clients. A poster for a theater troupe shouldn’t look like a financial firm’s prospectus. The words you’ve chosen should describe how you approach your work, rather than describing a personal or house style. Elegant, crisp, or confident are more likely to work for you than brash, sexy, or impulsive.

Adapting your content

You’ve now tallied up the self-assessment and have a profile of who you are—and how the world probably sees you—as a creative professional. In creating this profile, you’ve defined the work you’re qualified to handle, the range of work you’ve already done, and the type of employer or client you want. Ideally, these three areas connect elegantly. Most probably, there’s an inequality somewhere that you need to address.

Quality

Your portfolio is a kind of personal statement, so you want it to say what you really mean. Every time you include a project that is clearly inferior to other work you’ve done, you make the worst portfolio faux pas. You’ve said, “I am proud of this work. I think it represents the quality of material you will get from me.” By saying that, you’ve told the savvy reviewer that you can’t tell good work from bad. Or that maybe the good work you’re showing is a fluke and that most of the work you do is like the inferior pieces. Either interpretation will devalue your portfolio and all of the work in it.

Some people are aghast at this idea. “This is the only piece I have that shows I can design a website! Didn’t you say I needed variety?” Project variety is never served by variety of quality.

Eliminating bad work doesn’t always mean eliminating work you didn’t enjoy. There’s no excuse for keeping in an inferior personal project because a reviewer will assume that you had creative control over it. But there is an occasional real-world piece that may not excite you but tells something important about your skills. If you have other work that shows your creativity and one piece that shows you can deliver a finely crafted but boilerplate project, you might want to leave it in. In your explanation of the project, you can briefly discuss the constraints under which you had to operate.

Quantity

There are a lot of myths about how much work you should show in any type of portfolio, let alone a digital one. There’s no ideal number, but whatever it might be, people overwhelmingly err on the side of too much. Minimizing the number of pieces you show is a form of self-protection. It’s a lot harder to get sucked into showing an inferior project if you limit your total number of pieces.

Illustrators, artists, and photographers, who are responding to a different type of market, will almost immediately disagree. To tap the stock or clip art market, they feel that they have to carry an encyclopedic amount of work on their sites. Their error is in not making a distinction between their Flickr account or catalog site and their portfolio.

There are many outlets where you can display your oeuvre. Sites like Flickr encourage image makers to upload everything they shoot. But digital cameras and camcorders make it dangerously easy not just to shoot extensively—a blessing that photographers in the film age would have given their best lens for—but to post obsessively as well. That’s fine for sharing fun ideas or trolling for facile compliments. But a portfolio should contain nothing but the artist’s selects—a small fraction of your work. The person looking through a portfolio with money in her hand wants to know quickly about the artist’s style and how it plays out in some example projects. This need is best served by a small, exclusive collection of highlighted images. In contrast, anyone examining work on a stock or catalog site is looking for something specific. They will treat the site like a database or search engine and search by subject.

Reworking, rethinking

Once you’ve trimmed your expectations of how much work to show and eliminated any work that feels off, you may discover gaps in areas that you originally thought were well covered. If you really need an example of a certain type of work, you can return to a less satisfying piece and rethink it—pushing it harder to show that you know how it should have turned out.

Reworking is almost obligatory for any piece that wasn’t professionally produced, and the result can be very successful in a digital portfolio. In particular, animations and interactive projects are so comparatively easy to rework at the same level of production that you should never include a substandard one. Even with a site that was a live client project, you will boost your chances with a potential employer by showing how you would improve it.

You also have the prerogative of reworking projects that were OK but that suffered from built-in limitations. If your portfolio is chock-full of black-and-white line drawings and you are bored with working in black and white, why show a digital portfolio that will never get you a color illustration? Reworking an idea with fewer (or different) limitations shows versatility and enthusiasm for your work.

Creating your own projects

Based on your past projects, why would someone hire you? It’s possible that you love the work you do and hope a revised portfolio will help you to do more of it. But if you don’t have any good examples of the work you’d like to do, or any that can simply be revised, it’s time to invent your own.

Invention is not a lame response, or “make work.” Creative directors often look for freelancers and employees who will take initiative without losing sight of the project goals. If your portfolio shows evidence of these traits, you could very well beat out someone whose portfolio is stuffed with pedestrian color material, even though you have only one four-color piece (the one you invented). That can hold true even if the other person’s portfolio contains professionally printed samples, and yours are printed on an Epson. In a digital portfolio, where all surfaces become pixels, it might be enough to get you in the door.

Not all projects are equally worthwhile as professional hole-patchers. The sidebar that follows, “Classic projects,” is a starter list. Your best bet is to stick with projects that are realistic but that offer an opportunity to express your creativity. Unless you are inexplicably at a loss for structure, there will be plenty of time in your life to do product spec sheets, identity systems, and web forms. Just keep some ground rules in mind before you begin:

• Select a client first. Having a real-world company’s need to consider is much better than trying to imagine one.

• Develop for a different audience. Limited to the same old teen demographic? Try a company that sells to children, to retirees, or to farmers.

• Do your research. Take the project seriously enough to look at your client’s current material, and that of some reasonable competitors. What fresh and new approach can you bring to their work?

• Meet real design constraints. If you are drawing poster art, produce something using real poster dimensions. If you are designing a book cover or magazine, select a standard publication size. Making an identity? Be sure to use a mailable envelope size and standard business card dimensions. Reviewers will notice immediately if you haven’t done your homework.

Partnering

By now, you may have skimmed forward in this book and felt a little overwhelmed by how much work your personal project will take. As a result, you might be concluding that your only option is a group portfolio website or a social networking site, at least until you’ve mastered some new skills. That wouldn’t be the worst decision. But a lot depends on why you are making a portfolio and what your specialization is. If you belong to one of the professions that expect a unique statement online, or you feel strongly that you want to set yourself apart from others in your area, creating a personal site is still the best choice.

Instead, it might be time to ask yourself, “Do I need help?” There is no shame in concluding that you can successfully master some portions of designing and producing your digital portfolio, but not all.

Help can come in many forms. You can simply hire someone who fills the gap you see in your skills and experience. But it may be that the very reasons that you need a portfolio—short on work and cash—puts a hired gun out of reach.

If so, consider a creative partnership instead. Your partner may be a photographer who provides you with digital files of your projects. He may be a graphic designer who designs an interface for you. She may be a programmer who takes your graphic design and implements its interactive elements in Flash and JavaScript. Many times, partnerships are about bartering skills—a new business logo identity for one person, a photo shoot for another.

What you need in a partner

A partner should complement your own expertise and be someone whose work you are familiar with and respect. Ideally, he or she should be someone you have worked with on another project, so that you know what their strengths are and whether you work well together. Your portfolio is a very personal project, and the last thing you want is a partner who isn’t prepared to support you and your vision.

Be prepared to give full credit for your partner’s creative input. That probably means that you should not consider as a partner someone whose creative area you hope to make your own. If you are an established print designer with no desire to enter new media, it’s reasonable to partner with a new media specialist to write the program, create the database, and implement the navigation. It’s not reasonable to allow others to assume that you are a multimedia designer if someone else has created the concept and implemented the site for you.

Your role in the partnership

Although you should trust whomever you work with to know their own area of expertise, you should come to the table prepared to explain who you are, what type of help you need, and how much autonomy your partner will have. If the areas you need help in are areas you should ultimately know and understand, use your partnership as a learning opportunity.

Handle as much of the process as you reasonably can. Know your target market and how you want to be seen. If you’re working with a photographer, take some shots yourself from the right distance and angle, with your materials arranged as you’d like them. Decide what content goes into your portfolio and how you want your work grouped. If artwork needs to be processed and you don’t do it yourself, you should at least quality control (QC) every piece before it enters the portfolio to make sure it represents you well.

If you do not have Flash or programming expertise, you should at least have a hand in your portfolio’s concept, look, and feel. Even better, you should come to your meetings with a proposed design. Best, you should create the static artwork and partner with someone with UI (user interface) experience to implement it.

Last but not least, you should personally test the portfolio as it develops and before you post or send it. See Chapter 13, “Presenting Your Portfolio” for a discussion of how and what to test.

WWW.EMMANUEL-LAFFON.COM

Industrial designer Emmanuel Laffon de Mazières uses beautiful background photos as important elements on his portfolio site. He provides a credits link that not only alerts the viewer to photographer Keira Chang’s contribution, but provides a link to her Flickr site.

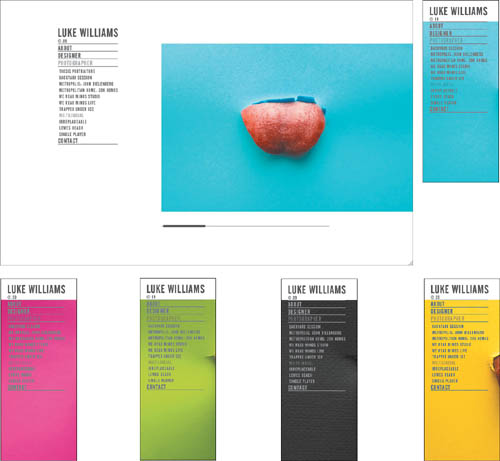

Portfolio highlight: Luke Williams with Jonnie Hallman | Partnering

By any reasonable measure, Luke Williams is a young graphic designer on the rise. On the dean’s list at the prestigious Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), a former intern at Pentagram Design, and already a junior designer at Under Armour, he could have decided to take the easy road on his portfolio. He’s primarily a print designer, and for many others in this category a well-designed PDF combined with a laptop slideshow and physical portfolio might be a fine combination.

But Williams doesn’t ever take the line of least resistance. He not only wanted a personal website, he wanted a project that would be more like a personal presentation. It should flow beautifully, showcase the work, and crack the anonymous web wall with a peek at a real person.

The about and annoucement pages are very understated. With their condensed, angular type and hairline rules, they echo the design of a printed page. However, they are legibly reworked for the web—an elegant translation of a familiar aesthetic to a new venue.

Laying out the design flats in Illustrator, Williams knew exactly how he wanted his site to function, but lacked the skills to implement his ideas. He was fortunate to have as a good friend fellow student and web designer Jonnie Hallman. As talented as Williams and with a shared aesthetic, he was a natural person to ask for help. Initially, Williams asked for “just” Flash tutoring. Hallman, knowing exactly what a time sinkhole that would be, secretly knocked out the initial programming as a personal challenge while they shared a movie rental.

When Luke decided to improve the site for version two, the favor for a friend evolved into a partnership, with Williams driving the concept and tweaking the design details while Hallman provided a working process that included design alternatives, feasibility feedback, and programming implementation. The result is an unqualified success, both as the embodiment of Luke’s personal vision and as an example of partnering at its best.

After the viewer selects a project, a set of gray windows sized to each project image builds on the screen, focusing your attention and defining the viewing area.

Navigation and architecture

The navigation is both simple and enormously sophisticated. Although the site is obviously built with Flash technology and uses it well, it avoids busy Flash effects.

The narrow menu anchors the left vertical plane, with project titles expanding below when the main category is selected. Active categories and projects are indicated in gray, as are rollovers that “anticipate” their selection. The only other navigation element is a slender slider bar below the project images. Clicking on the bar and sliding to the right scrolls project images horizontally. Design projects are either sequential spreads or are organized visually to help the visitor explore the project. Photographs describe small narratives, and are sequenced by chronology or subject.

One of the most striking aspects of the navigation is revealed as you scroll. The menu remains firmly in place as an active element while the project work scrolls transparently behind it. This extremely usable idea is the most visible example of the Williams-Hallman creative process. As Luke says, “That was one of the things that Jonnie surprised me with. I realized that the menu wasn’t going anywhere when I scrolled through the pieces. I was curious about how people would respond to it. In hindsight, I liked it and I wanted to keep it like that. It echoes the announcement text on my home page. It’s all about me talking to the viewer. I’m always in the fore-front, and what’s behind me is my work.”

Content

Williams’s content is clearly displayed in his menu, and falls into three categories: Designer, Photographer, and About. The majority of work is found under the category Designer, and is organized chronologically, with the most recent project at the top of the menu and therefore the first one a visitor sees. The projects have short, descriptive labels, but stand on their own as visual artifacts without project briefs.

Williams offers a second category of work in his photography, some of which he created for clients, and the rest of which is personal artwork. However, he never makes the mistake of confusing the viewer about his professional focus. Even his narrative photography has a strong design aesthetic.

His announcements are content as well—frequently updated ephemeral bulletins about his creative life that appear on his splash page. These updates are common on Facebook but unusual in a portfolio. Williams explains, “It’s a way to speak about my work and process. I want viewers to know what I’m up to, and that I am a real person. And most importantly, I want you to feel like I am approachable. I get emails from people telling me that they saw my site and really enjoyed the experience, and I wonder if the announcement column deserves some credit.” Expressive and humanizing, the announcements are great examples of portfolio text done right, and have become a signature part of his personal graphic identity.

Future plans

The format, based in sophisticated Flash programming, might seem to be a future barrier. How will updates take place? Once again, a smart partnership prepared for this. Hallman created a document in XML, an easy markup language that Flash can read, then gave Williams a crash course in XML’s basics. Williams can change some parameters, cut and paste text, and upload a document, allowing him to not only add individual projects and change text at will, but even add new sections to the menu.

Williams has been hired by Chicago-based advertising agency Leo Burnett, which should lead to a wide range of projects and a diversified portfolio. Although every web site eventually gets redesigned, he feels confident that the current version will stay fresh for now: “I’ve tried to provide an intuitive experience for the viewer. There isn’t much I would want to change or add to the site, and I actually have yet to encounter a project that does not translate well in the format I’ve given myself.”

When you hover over an image, you have the opportunity to enlarge it. The enlarged image is not a zoom of the original shot, but a larger image of the entire piece, allowing the viewer to examine the details.

Williams’ wry photographic essay, Multilingual, displays a variety of tongues in different color fields, and illustrates one of the navigational challenges Hallman solved. Given the variety of color and value in Williams’ images, leaving the menu one color as the artwork scrolled behind it would impair legibility. Hallman programmed the menu so the type would respond to the individual background colors.