Chapter 2. Professions

Portfolios are bound together by the personality and goals of those who create them. When you define the type of work you want and identify yourself within it, you lay the first building block for your unique portfolio.

Defining your place in the world can be surprisingly complex. You might apply for several art director positions, only to find that this title means different things at different companies. Each one puts their own spin on how much experience and what talents and skills the position demands.

If you want to work on electronic media projects, do you call yourself a graphic designer? Sometimes graphic design equals print design. An interface designer? You need to know something about interface design to design a website. But interface design—the “human factors” part of design—is often handled by a person with an engineering or industrial design background. Then there’s the interactive designer—the person who designs a project’s look and feel. A Flash developer may play that design role, as well as do production and scripting. Some media creatives prefer the term experience designer. People in the industry will know what this means, but it will mystify most potential clients.

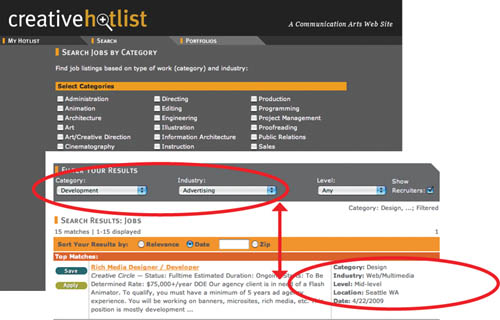

WWW.CREATIVEHOTLIST.COM

The Communication Arts job website has finely tuned its subject list. But many of the jobs are cross-listed, like this one for a multimedia Flash developer, which is also listed in the Advertising industry and the Design category.

Does this seem like splitting hairs? Maybe. But if you make the wrong choice as you develop your portfolio, you could end up doing work you don’t like—and in the wrong industry. You should emerge from this chapter understanding the portfolio expectations for your creative niche and how to mix different types of projects to meet those expectations.

Purpose

The elements of a portfolio are basic, but how you mix them depends on your immediate need—the life change that is prompting you to create or update your portfolio. Are you developing and presenting it...

• For professional growth and discovery?

• For acceptance into an academic program?

• To curators or gallery owners?

• To provide elements for a larger project?

• For a full-time job?

• To gain or retain clients?

Your purpose will color the type of work you include, its format, and your presentation. It will interact with the following portfolio ingredients to create a framework that is specific to your industry.

Portfolio ingredients

It’s obvious that a portfolio isn’t worth much unless it contains good work. But good work alone isn’t always enough. Every profession has a different definition of what “good” is. What works magnificently when you present to an art director who needs an illustrator will fall flat when she needs a freelance designer—and vice versa. For each role and audience, your portfolio must contain the right kind of work, in the right format. Meet the unspoken assumptions, and you send the message that you know who you are and what you want to do.

That’s good advice, you may be thinking, but not very practical. How do you know what’s needed when? It’s hard to answer that because every hiring situation has unique requirements, and every portfolio is individually created. But there is a short list of underlying elements that, when combined in appropriate proportions, can help to craft a portfolio that speaks effectively to its intended eyes and ears.

The following ingredients appear in different proportions in each creative profession’s portfolio. A bar keyed to each category indicates their relative importance for each area. Like a great chef, use these recipes as guidelines, not laws, for finding the uniquely right proportion for your work.

Variety

![]()

You might think that variety would be a plus because it shows the full range of your work and capabilities. Sometimes it is, but you’d be surprised how often it works against you in some professions. If your pieces are too diverse, in medium, look, subject, or clientele, they can imply that you haven’t yet figured out what you do best—and that you have yet to find your creative voice.

Style

![]()

As artists and designers mature, their work frequently develops a creative signature. For some professions, an identifiable style is nothing short of a requirement. For others, it’s intrusive, like an out-of-tune voice in a chorus, because it gets in the way of a client’s message.

Concept | creativity

![]()

There is a difference between creativity in your portfolio content and creativity in your presentation of that content. Some professsional areas expect the portfolio package in any medium to be a beautiful creative artifact. Others consider a high-concept presentation to be a nice touch, but it is not required. For a small number of portfolio types, too much attention and creative energy spent on the portfolio concept is probably a waste of time.

Process

![]()

Work in process, or work about your process, can indicate how you evolve your ideas and what it would be like to work with you. In many professional situations, how you think and problem-solve can be as important as your aesthetic decisions. For professions where production is expensive or time-consuming, process work and prototypes are so important that not showing them is suspect.

Technology and craft

![]()

Bad craft and inappropriate technology are always negative, but for some professions, they’re a much bigger issue than for others. Many fine artists create personal websites that use text or navigation badly. These lacks can be painful to those in the know, but a potential curator will just go straight to the work without noticing. Weak craft in a design portfolio, on the other hand, is never forgiven.

Your portfolio mix

How you approach your portfolio—digital or traditional—should depend on your purpose and the category of creative professional you are. The following descriptions define these categories. They’re followed by examples of how your category interacts with a likely purpose. These templates will help you determine your ideal mix of portfolio elements, unify your portfolio, and emphasize your strengths in the context of your professional needs. Hopefully, they’ll also make it clear how important it is to have a portfolio that is organized and modular, so you can reconfigure it as your situation and needs change.

As you read the following descriptions, concentrate on the one that fits you best. You’re required by the way people evaluate your work to choose a category and stay consistent within it. Does your work, your chosen market, and your current portfolio seem to work within the framework of one of the descriptions below? If it works within more than one, you may be a highly versatile person, but you’ll either have to make a choice, or you’ll need to create more than one portfolio. (Check out Chapter 4, “Delivery and Format,” for more on multiple portfolios.)

Art

This category is made up of people who have considerable control over the subject, message, media, and presentation of their creative work. That freedom usually extends to the digital portfolio. If you want to make art for commercial purposes (like an illustrator) rather than sell or exhibit art that you have made for personal expression, you should look at the other categories instead of or in addition to this section. The two portfolio purposes really shouldn’t mix, as they have different audiences.

Student | for admission

![]()

Students belong in the art category because their primary focus isn’t (or shouldn’t be) making a living from their artwork—although every student would much prefer to freelance for spending money than to wait on tables. Being a student is a transitional state. Because you’re still on the road to your goal and able to change focus as you experience new options, you can create a portfolio that includes many facets of your creative life.

Admission portfolios are special: The people judging your work tell you exactly what they want to see. Don’t take this gift for granted. Meet the requirements as closely as you can. If digital portfolios aren’t mentioned as a submission medium, don’t send one, even if all your artwork is computer-based. Some academic institutions are just old-fashioned, and the admissions committee isn’t comfortable handling technology. Others are perfectly adept with computers but have very good reasons (see Chapter 4) why they may not welcome discs.

In general, an admissions committee is looking for variety in order to assess your strengths, weaknesses, and level of preparation. In undergraduate portfolios, craft is seen as less important than potential because technique and good habits can be taught. Don’t attempt a high-concept presentation unless you are applying to graduate school in one of the design professions. Such professions also take craft issues much more seriously for graduate students, particularly if the applicant has already majored in art or design as a undergraduate.

Some college art departments help to encourage good quality student digital portfolios by developing portfolio templates. This one, developed for Art+Design students by the Educational Technology Center at Northeastern University, allows students to customize background, colors and content. It puts a clean Flash presentation within every student’s reach.

Fine artist | for exhibition or commission

![]()

A fine artist is someone who views his or her work solely as a means of creative, social, or philosophical expression. An artist doesn’t need a digital portfolio in the same way that a designer or illustrator does. However, the benefits of personal marketing and networking outside a geographical area have persuaded many fine artists to use an online outlet for their work. You’ll seldom get a show or a commission based on your digital portfolio alone, but if you’re lucky it could open the door to a studio visit or an invitation to a competition.

The art world was slow to accept any merger of art and technology, including that of traditional art forms with a digital portfolio. That has changed. Curators who are sticklers for tradition still consider 35mm slides and transparencies de rigueur, but fortunately, their numbers are shrinking. No matter how much an artist hates technology, he should at least have a small space on one of the many group or art catalog sites for prospective clients or curators.

WWW.ARTN.COM

(art)n—Art to the Nth Power—is a collective led by renowned graphic artist Ellen Sandor. (art)n highlights its virtual artwork—virtual photos on a range of topics, rendered with rich photorealistic depth—on its site. The home page is a slideshow in a minimalist but technically savvy interface, designed by Janine Fron and Jack Ludden.

As a fine artist, variety works against you. The art world looks for a unique, consistent style. Only after developing a track record of successful shows can you combine multiple interests and media in one portfolio. Unless your artwork involves technology, craft is only relevant in that bad craft can push people away. The fine art digital portfolio should keep its focus on the work, minimizing presentation concept.

2D graphics

Three groups of image-makers belong here: people who compose and/or shoot live images, those who create images through multiple forms of image capture and digital compositing, and those who draw or paint pictures—either in traditional media or on the computer. The groups can be fluid, although photographers and their clients tend to view most computer image compositing (as opposed to image enhancement) as a form of illustration. For convenience’s sake, I’ve combined compositors and illustrators into the Graphic Artist category.

Photographer | for license or freelance

![]()

Photographers capture images, either digitally or on film. They were among the first artists to use digital media to archive, display, and sell their work. Unfortunately, with the near-universal ownership of good digital cameras and Photoshop, more people create images that are (at least online) competitive in quality with the work of established pros. By creating an enormous searchable library, Flickr has made it difficult for a photographer to justify building their own portfolio of stock images, which was a major way to drive online income for professionals only a few years ago. In this new environment, photographers’ portfolios must stand out, both in the type of work they contain and the sophistication of their presentation.

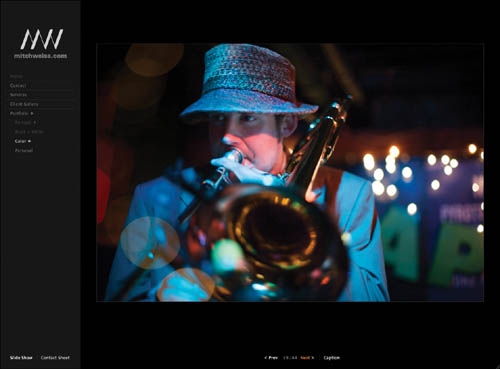

WWW.MITCHWEISS.COM

Mitch Weiss is a prime example of a professional photographer who is comfortable with website development and has given significant thought to how he presents his work online. His site enhances and showcases his strengths in portraits and commissioned work.

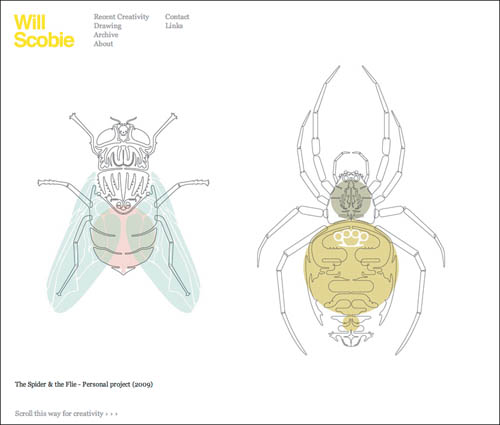

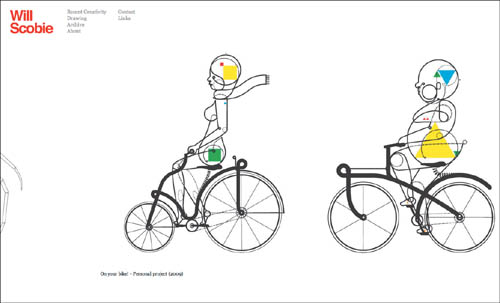

Graphic artist | for license or freelance

![]()

Illustrators and fine artists often use the same tools, but to different purposes. Unlike fine artists, illustrators create artwork on assignment. Like artists, they must project a unique stylistic identity and approach. They must be not only talented and skilled in their media, but also good at interpreting and executing client ideas.

Like for fine artists, style is the most important element in this type of portfolio. But the bar is much higher in the concept and execution of a graphic artist’s web portfolio than it is for a fine artist. Graphic artists should consider splitting their material between a site like Flickr, where they can post volumes of work that can range from experiments to commercial work for inexpensive licensing, and a personal site for higher-end commissioned and concept work.

A freelance illustrator’s portfolio should complement the artist’s style the way a good matte and frame enhance a 2D graphic. The concept is very important. In both cases, technology and craft must be fluid but largely invisible.

WWW.FLICKR.COM/PHOTOS/WILL_SCOBIE/

Will Scobie takes advantage of Flickr’s great organizing tools and presence online. He draws copiously, and puts the results of loose, fun work on envelopes, scraps of paper, or in formal sketchbooks where they will be seen, but not confused with his more formal, developed work.

Design

The design professions share a common ground in their roles as interpreters, integrators, and collaborators. Although there is little fluidity across the spectrum of design professions (architects don’t usually design annual reports, any more than designers create elevations) there is quite a lot of crossover at the edges. An exhibit or experience designer might have been trained in architecture, industrial design, or graphic design.

Architect | for commission or full-time

![]()

An architect designs buildings, interior spaces, and landscapes—the interactive space of the real world. Because of the stakes involved, the architectural profession has a strong commitment to apprenticeship. A new architect can expect to spend time in a CAD support role before they are trusted to take part in the design process, so their technical skills must be strong.

Although most young architects have some form of digital portfolio, it is often an exact digital rendition of the traditional print-based archive of models, elevations, plans, renderings, and photographs. Architectural firms concentrate more on photographs of finished work online, but even established professionals often show projects that did not get built or produced in their portfolios. There will always be more design ideas than there can be actual commissions.

ISSUU.COM/GRACEFULSPOON/DOCS/080206_ARCH_PORTFOLIO

As this flat from architectural student John Locke’s online portfolio attests, an architectural presentation should emphasize all stages of the development cycle, from first sketches to the completed project.

Industrial designer | for commission or full-time

![]()

Industrial designers design products and systems. Excellent 3D visualization talent and sketching skills are important prerequisites and play a big role in their portfolio presentations. Their strengths in usability and navigation make them naturals for careers in multimedia design. Although industrial designers overlap architects in many of the technical tools of their trade, their portfolio requirements diverge. Unlike architects, ID portfolios are frequently digital, both in web and CD form.

Young 3D designers, even ones with great creative promise, will spend their first years exercising their modeling or drafting expertise. A portfolio that doesn’t display the highest possible professional craft with the widest variety of tools will go to the bottom of the pile. Process is very effective as well. In addition, usability is often a major design issue, particularly for product designers, making a great, elegantly conceived online portfolio a bonus.

Graphic designer | for freelance or full-time

![]()

A graphic designer combines text, image, and sometimes sound to visually communicate ideas and solve strategic and marketing challenges. Graphic designers are more likely to deal with 2D projects, but many also design packaging, signage, and, of course, interactive sites. A graphic designer with a good eye for space might design a store interior as part of a client’s overall branding and marketing system.

The format and design considerations of a graphic designer’s digital portfolio will almost certainly be affected by the type of work in which the designer specializes. A package designer may have a portfolio that is formatted more like that of an industrial designer because so much of the work is 3D. Corporate identity designers will often show more process and speculative work.

Pieces that display good visual thinking will be more effective than pedestrian desktop publishing, even if one piece is a student project, and the desktop work is professionally printed. The graphic designer’s portfolio concept will be looked at very carefully by any prospective employer, even if that designer only does print work.

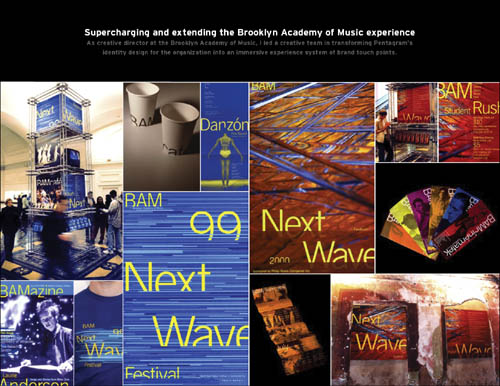

JASONRING.COM

Ring is a multitalented identity and brand design specialist. Every page of his PDF portfolio is designed with a keen eye for color and form. His collage of project images show a mastery of small as well as large-form print matter.

Multimedia designer | for freelance or full-time

![]()

Unlike graphic designers, who also may do multimedia design as one medium among many, a multimedia designer is most comfortable designing for the computer screen. Multimedia designers are expected to be extremely technologically adept, and their portfolios should display these skills.

Technical presentation, flair, and attention to detail are particularly critical for the design portfolio. Variety in project and approach are encouraged. Because of the emphasis on how you think, a design portfolio is a great place for process and personal project work. Craft is also highly regarded.

The designer’s digital portfolio requires a concept that not only presents the actual work well but is a design project in itself. This “wrapper” is frequently interactive, although for a print-based designer, interaction might mean a simple linear slideshow instead of a complex, multilayered experience.

A multimedia designer’s digital portfolio is more technically demanding, and an elegantly designed and executed “wrapper” is often a plus. Considering that you might have created sites that have been redesigned (or closed down) after you worked on them, showing prototypes or work in process is often a necessity. This portfolio is often a design object in its own right, but the portfolio should not be allowed to overwhelm the projects.

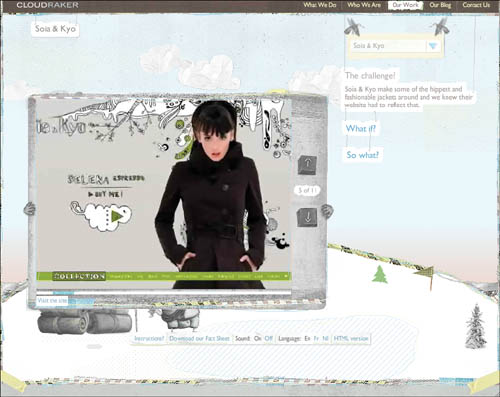

WWW.CLOUDRAKER.COM

As a company that specializes in multimedia experience design, CloudRaker has to meet high client expectations; their work and their portfolio site must be smart and on the cutting edge of technology.

Production developer | For freelance or full-time

![]()

Designers or graphic artists sometimes apply for production positions in a soft economy. If you fit this description, you may need a different balance of work in your digital portfolio than the one you use when applying for a creative position.

A production specialist is hired for one reason only—to implement—whether they are writing JavaScript, optimizing graphics, or creating Flash-based interaction. Creativity and a good eye are a bonus, not the main event. A professional developer knows this and prides herself on her speed, efficiency, and accuracy, even under pressure. This pride should be on display in a production portfolio’s exquisite attention to craft and detail. Process and variety are still useful.

Motion and interaction

Designers and illustrators are adding time and motion to their repertoire of tools and media. There is a difference, however, between incorporating interactive elements into a design and concentrating on movement and imagery. Motion graphics professionals incorporate performance and storytelling into their visual skills.

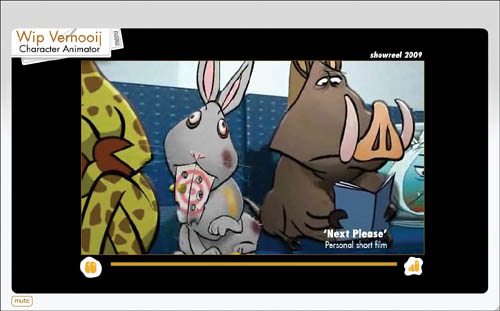

Animator | for freelance or full-time

![]()

Animation was once identified exclusively as hand-drawn cartoon entertainment. Today, most animation is computer-based or -assisted. Computer animators make it possible to “walk through” designed virtual spaces, visualize abstract scientific principles, and merge real and imaginary elements seamlessly in film.

Technical virtuosity goes hand in hand with creativity in a time-and-motion portfolio. Variety is prized, as is a clever concept for editing clips of work together. Sound is a part of the palette and should be an integrated component in the portfolio. Process is useful in a supporting role. Personal projects are expected to make up a large percentage of an animation portfolio until the animator has been working professionally for many years.

Videographer | for freelance

![]()

In a quick and simplistic analogy, a videographer is to a photographer what an animator is to an illustrator. Instead of capturing and editing individual still frames, a videographer captures moving images. Videographers are usually freelancers who not only shoot the content but handle post-production as well. Their portfolio samples are provided in the same range of format and quality as animators’ work, although there are usually fewer individual projects, and longer sample clips. Variety of subject matter and evidence of good technical skills are extremely useful.

Because both animation and video projects are extremely time-consuming, work in process or personal projects are not only acceptable in the digital reel, but expected. So are other goodies—tutorials or personal projects—that show technical mastery behind the scenes.

Portfolio sites by both video and animation professionals are often simple static sites that are used as a download space for the actual portfolio—the demo reel. No longer a literal reel-to-reel analog film, today’s reel is always digital, saved with different compressions for different purposes. The first is a highly compressed, low-bandwidth sampling appropriate for YouTube or similar sites. The second is a large, high-resolution version that can be downloaded and viewed locally or handed off on a DVD. In addition, some motion professionals offer a third version at a compromise resolution for display on a personal website.

WWW.WIPVERNOOIJ.COM

Freelance character animator Wip Vernooij’s demo reel displays his talent, attention to detail, and sense of humor. It includes both professional work and personal projects.

Game Design

Game design is a collaborative category that comprises a range of specialists from established creative areas—illustrators, animators, interactive designers, information architects, programmers—who come together to create and develop a form of digital play. These specialists tend to place the word game prominently in front of their discipline, but they create portfolios or reels appropriate to their specialty. Illustrators and animators create game art, for example, that they display in ways entirely consistent with illustrators and animators who create for other categories. Specialists in interaction, environments, and built spaces are often game level designers. Game programmers will usually provide demo code and will work with game artists to create a DVD that contains a playable game prototype.

Most creatives in the game industry at the technical-creative end work full-time for game companies. Because no game engine has emerged as a standard, it is common for game design programmers and designers to use one or two prototypes as content for a portfolio reel to land an entry-level staff position. Once there, you’ll master the company’s specific engine or apply a programming language in a proprietary project.

Game artists, on the other hand, are frequently hired guns who move from project to project. Their portfolios tend to combine the game aesthetics of 2D or 3D play with the guidelines of their basic area—storyboard or character design artists have online or disc portfolios that look like illustrators’ portfolios, while game animators’ portfolios are always demo reels, with or without a designed wrapper.

Performance

Performing artists have joined the ranks of creative professionals presenting themselves digitally. Standards for performance digital portfolios are still evolving. Aesthetic expectations are still fairly undemanding, but seamless craft and good quality film resolution can be very important. A digital portfolio offers the opportunity for a performer to establish credibility and to provide a more professional presentation. However, as most performers do not have training in the visual arts or programming, it’s usually best to hire someone to follow the professional guidelines—good quality video samples of your work, one or more high-resolution images of yourself, and a well-designed resume in PDF form.

The grain of salt

Don’t be surprised if you come across portfolios of senior professionals that stretch the limits. These profiles can’t represent the state of the profession for everyone at every point in their careers. When an individual moves upward professionally or carves a unique niche, he or she can salt the common wisdom to taste. If you are just starting out, are trying to improve your chances, or are shifting into a new area, you can’t. Although you can, and should, push yourself to offer the most creative and innovative presentation and work that you can, pushing far beyond the guidelines may simply make your audience think that you don’t know what those guidelines are. That’s a particularly important idea to keep in mind as you move from a general understanding of your profession’s expectations to the specifics of who you are in relation to your chosen audience.

Portfolio highlight: Will Scobie | Primary directive

Generic portfolios are like clichéd characters—we know what to expect and we’d rather not waste our time. Ideally, every portfolio should be lively and unique, just as we are.

But having a creative signature doesn’t mean that a portfolio shouldn’t reflect its artistic origins. Like you can tell bruschetta and sushi apart at a taste, spending a few seconds on the home page of a great portfolio should immediately telegraph whether you are sitting down to design, animation, or illustration. Spend a bit longer, and the individual personality should burst through. You’ll savor every project, enjoy the presentation, and talk it up to your friends. Illustrator Will Scobie’s portfolio explodes with personal style and makes you sure that you would like the person who provided the feast.

Navigation and architecture

A good structural architecture always serves as a strong skeleton for a portfolio. But nothing shows better how important the maker’s personality and its creative expression can be to the portfolio’s impact than a quick comparison between Luke Williams’ portfolio in Chapter 1 and Scobie’s here. Both portfolios use a horizontal scrolling system. But other than this fact and their shared excellence, the two creative expressions have little in common. Scobie’s portfolio is as free-form as Williams’ is crisply designed.

It’s clear that Scobie is his site’s designer. The website looks and feels exactly like one of Scobie’s illustration projects, rather than a generic matte and frame, or an outside wrapper with another artist or designer’s imprint. Much of his artwork, like his website, unfolds like a paper scroll. Looking at the horizontal pieces on his site imposes a linear narrative on the unfolding sequence, and encourages the viewer to linger on the individual characters and drawings to check out the details.

Site navigation is compactly nested next to Scobie’s name, and is very simple. The menu text brings you to individual gallery sections, each of which is either below the menu on the screen or viewable by scrolling right. Click his name and you’re returned to the home page animation.

Scobie’s site is built around the primary colors of yellow, red, and blue. It opens with a clean and graphically simple but mesmerizing animation. The simple circles suddenly become the frame for a complex sketch made from one continuous red line, an illustration that exemplifies his style.

Each menu item highlights in one of the three colors. Roll over the name, and it changes to a primary color or to black.

Content

Scobie’s work is loosely divided into three categories. Recent Creativity and Archive are chronological, with Recent Creativity positioned in the menu to encourage people to view it first.

Work in the Drawing section exhibits a distinctly different feel from the rest of Scobie’s work. Putting this work in a separate gallery space is a very smart decision, as an illustrator’s style is his most distinguishing selling point. People can explore this area, but prospective clients are channeled first to the “Recent Creativity” section, where his identifiable style predominates.

Another smart decision is what is not on the site. Many creatives struggle with how to categorize and present their material in one place. How much is too much? What will clients want to see, as opposed to other artists or friends? Visit Scobie’s Links menu and you’ll find a list of self-publishing sites. Although part of his strategy is just to get his work out into the world as widely as possible, he’s selected each site for a purpose. Each contains a diffent type or mix of content: artist notebooks and work in progress on Flickr, thoughts and comments on specific projects in the blog.

Except in the Recent Creativity section, where the most recent project pushes the older one to the right, the artwork is not arranged in any particular order. In this case, the lack of regimented structure is very consistent with the playful and surprising character of Scobie’s work.

The Drawing section is a nice counterpoint to the rest of Scobie’s site. Scobie’s very identifiable style is graphic and somewhat geometric. These sketches still have the flavor of his other work, but are less commercially focused.

Use the scrollbar to see an unfolding stream of work. This delightful piece has distinct segments that loosely correspond to the way you would see the piece evolve onscreen.

By offloading his wide variety and enormous output of work to other sites and using the portfolio website as a place for polished, completed projects only, Scobie makes explicit in the virtual world what was once standard practice in the analog one: segregating the “cream of the cream” in a portfolio, while inviting Scobie fans who want to go deeper to visit his artist’s studio—in this case, Flickr and other self-publishing addresses. Everything is available somewhere, but the audience can’t confuse concept and completion.

Future plans

As of this writing, Scobie’s site is very new, and he has no immediate plans to change it. As Scobie says, “Before my current website I had a Flash-based site, which I felt restricted the way in which I could display work. My current site was built using HTML and CSS, which allows me to show off my work at its best.”

The loose breakout by chronology makes it easy to update, and as recent work gets older, it takes its place as the first-seen work in the Archive. Because Scobie uses self-publishing sites for work of the moment, he feels no pressure to make his portfolio site bigger or update it more than once a month.