If the composition, blocking, and camera movement shapes the visual look of your film, lighting determines what the look feels like. No matter your lens choice, proper exposure, and ISO setting, a lack of understanding how to utilize light will destroy your cinematic look. A cinema-like camera will not provide a cinema look alone. Lighting is your most powerful ally in helping you sculpt a film look. Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC (The Deer Hunter), says that the “type of lighting we use actually creates the mood for the scene.”1

This mood is what you, as the DSLR shooter, must try to shape and capture with your camera. It helps provide visual depth to your picture. If you shot an off-white subject against a white wall, there’s not much contrast—not much light and shadow—and the picture appears flat. If you shoot somebody white against a dark background, the person stands out, and if you add background lighting to the scene, the depth increases. DSLR cameras maintain a strong advantage over HD video cameras because they have the capability with larger chips and ISO settings to shoot in natural and practical low-light situations, so fewer lights are needed on set.

The quality of light refers to what it looks like and what it feels like. What it looks like is what you see on the surface. The feel, on the other hand, conveys the emotion shaped by lighting. You can craft the look and feel of a film by paying attention to:

1. Light quality

2. Light direction

3. Light and shadow placement

4. Color temperature

LIGHT QUALITY 1: SHOULD IT BE HARD OR SOFT?

Hard light is direct, producing harsh shadows, and results in a high level of contrast. This can come from a sunny day or an unshaded light pointed directly at a subject. Hard lights are especially effective as backlight and rimlight sources, such as the example in Figure 2.1.

FIGURE 2.1 Vincent Laforet chooses to use a hard light source, not only casting a shadow, but bringing out the texture of the flowers due to the placement or light source direction from the side. Lights from headlights of a car with a white reflector were used for this shot. Lens: 50mm, f/1.2 shot at f/4.

(Still from Reverie. ©2008 Vincent Laforet. Used with permission.)

Craft the look and feel of a film by paying attention to:

1. Light quality

2. Light direction

3. Light and shadow placement

4. Color temperature

Soft light is indirect, created by reflecting or diffusing the light—an overcast day or a scrim or sheet dropped between the light source and the subject, or simply bouncing light off a white art board, or even reflecting light off a wall or ceiling. This type of light provides low contrast to the image (see Figure 2.2).

FIGURE 2.2 The waiting woman in Laforet’s Reverie is cast in a combination of hard and soft light. A rear three-quarter key highlights her hair and cheekbone in hard-quality light, while her face and chest are filled in with soft red light—actually lit from the taillight of a car to get the desired effect. (See Figure 2.17 for a lighting diagram of this shot.)

(Still from Reverie. ©2008 Vincent Laforet. Used with permission.)

One of the counterintuitive properties of light is the fact that as the lighting instrument is brought closer to the subject, the softer the lighting gets, while farther away, the harder it is because it becomes more of a point source, causing the hard light quality to stand out. A diffused light source from farther away may convey a harder light quality than a low-watt Fresnel lamp up close.

LIGHT QUALITY 2: DIRECTION

The direction of the light will determine the placement of shadows and, consequently, the physical texture of objects and people. There are fewer shadows when the lighting is on-axis of the camera (the front). Shadows increase as the light shifts off-axis of the camera and to the rear of your subject. Light from the side will increase the texture of the scene. When lighting is “motivated,” it refers to a light from a particular source, such as a fireplace, window, lamp, or the sun. In the medium close-up of the woman in the still from Laforet’s Reverie (see Figure 2.2), the hard light source is from the three-quarter right rear position, elevated above the actress’s head, the light motivated by a streetlamp. Background streetlamps provide ambient lighting, while fill lights from the front—lights either bounced or scrimmed—provide a soft look and feel on the woman. Although the red light isn’t necessarily motivated, it conveys an emotion Laforet wanted in the scene. The saturation of color is more prominent when the source is from the front, while colors become desaturated when the lights are placed in the rear.

Light Placement Terminology

• Key: The main light source of the scene (a window, a table lamp, overhead lighting, a fireplace, and so forth). Know where your motivated light source is and add lights, if needed, to reinforce it accordingly. Can be hard or soft quality.

• Fill: Lights used to fill in shadows caused by the key light. Usually a soft quality.

• Back and Rim: Lights placed behind characters to separate them from the background. A rim light specifically is placed high with the light falling on a character’s head, her hair lit in such a way as to differentiate her from the background.

• Background: Lighting occurring in the background of the set, designed to separate it from the foreground, giving the scene visual depth. These could be street lights, lights in a store, a hallway light inside, and so forth.

Following are a series of stills from a variety of DSLR shooters’ work, each one illustrating a different light source direction.

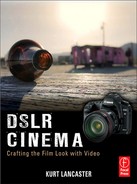

Light Source Direction: Side

A side key light on the front of the face brings out the main features of the character, the emotions expressed by the face (see Figure 2.3).

FIGURE 2.3 In Philip Bloom’s San Francisco’s People, he utilizes practicals from street lamps to light his subject. (See Bloom, P. (2009). San Francisco’s People: Canon 5DmkII. <http://philipbloom.co.uk/dslr-films/san-franciscos-people-canon-5dmkii/>.) Shot handheld with a Canon 5D Mark II; 50mm f/1.2 lens with Zacuto Z-Finder (eyepiece adapter).

(©2009 Philip Bloom. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 2.4 In this still from Rii Schroer’s 16 Teeth: Cumbria’s Last Traditional Rakemakers (featured in Chapter 9), we see how Schroer utilizes side lighting to highlight the features of her subject. Side lighting brings out texture because it reinforces shadows, as we can see with the man’s wrinkles (on-axis light will lesson shadows). Fill light reflects back onto the man’s screen-right face to help ease out the shadows (light from a window). Backlighting provides a sense of depth to the frame. (See Schroer, R. (2009). 16 Teeth: Cumbria’s Last Traditional Rakemakers. Vimeo.com. <http://vimeo.com/4231211>.) Shot on Canon 5D Mark II; Canon 24–70mm/2.8 lens.

(©2009 Rii Schroer. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 2.5 Another still from Rii Schroer’s 16 Teeth reveals how one key source light from the 180-degree rear offers a silhouette effect (the camera is exposed for the outside). Some of the light spills into the room, providing detail on the workshop table, but with no additional lighting we do not see details of the subject. Shot on Canon 5D Mark II; Canon 24–70mm, f/2.8.

(©2009 Rii Schroer. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 2.6 Ken Yiu utilizes a ¾ rear to shape a backlighting look that creates a contrast by putting the woman’s screen-left face in shadow, but enough on the screen-right side to give us a dramatic expression. (Yui, K. (2009). Y. Lumix GH1-Wedding Highlights. Vimeo.com. <http://vimeo.com/6272661>; normal shooting mode, kit lens: 14–140mm, f/4–5.8).

(Still from Wedding Highlights. ©2009 Ken Liu. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 2.7 This full frontal key light from Philip Bloom’s A Day at the Races (featured in ) brings out the full emotion of the character, while minimizing texture. Notice the eyes have a glint in them. Frontal lights make characters come alive through these types of tricks. Some cinematographers will add an eye light to bring liveness to the shot. Shot on a Canon 7D, modified with a PL mount with a Cooke lens (100mm). (Bloom, P. (2010, March 10). A Day at the Races. PhilipBloom.net. <http://philipbloom.co.uk/2010/03/07/races/>.)

(©2010 LumaForge, LLC. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 2.8 This still from Vincent Laforet’s Reverie utilizes a ¾ frontal key (Profoto 7B head with reflector and modeling lamp with bare head) from a high angle, emphasizing the beauty and dramatic look of the woman. Backlighting is shaped from available (practical) street lamps and also causes shadows to fall into the foreground of the shot. The higher the backlight, the shorter the shadow on the ground (but not the face). Shot on a Canon 5D Mark II, 50mm lens at f/2.

(Still from Reverie. ©2008 Vincent Laforet. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 2.9 The setup for the shot featured in Figure 2.8. Vincent Laforet, screen right, sits behind the camera, while we can see the breaklights on the vehicle casting red light onto the model.

(Photo courtesy of Vincent Laforet.)

Note: If you’re shooting in the daytime and need to make it look dark, use blue gel filters with a high hard light (representing the moon) and desaturate the colors.

LIGHT QUALITY 3: LIGHT AND SHADOW

Shadows bring out drama and are essential when creating a night scene (see Figure 2.10). Related to light direction is the placement of shadows. The direction and height of the light determine how shadows fall in the cinematographer’s composition. Lights from the front will minimize shadows, whereas lights from the rear will increase the amount of shadows seen on camera. The higher the light source, the shorter the shadow. If you want long shadows, shoot at sunrise or sunset, or place your lights low, instead of high, in the background. Side lighting will increase texture.

FIGURE 2.10 In the opening sequence to Laforet’s Reverie, we can see how he crafted a night look for this scene. Soft light (with a blue gel to color the scene) from above left lights the actor’s face, while one from the front hits his feet. The light is tightly controlled, minimizing spill, so as to enhance the shadows in the space. The lack of a backlight also helps accent the darkness and provides the night-time feel.

(Still from Reverie. ©2008 Vincent Laforet. Used with permission.)

LIGHT QUALITY 4: COLOR TEMPERATURE

DSLR cameras see lights differently than people do. Their computer chips are not as smart as human perception and have a hard time adjusting precise and subtle differences in color caused by different kinds of light sources. Different chemicals burn at different wavelengths, producing different color qualities depending on whether the lamp is halogen, tungsten, fluorescent, sunlight, and so on. Also, sunlight changes its color temperature depending on the time of day and whether or not it’s cloudy (see Figure 2.11). Color temperature is measured in degrees Kelvin (K).

FIGURE 2.11 An overview of the color tones during different times of day. Sunset can also refer to sunrise. The warmer and cooler label refers to the quality of the tones, not to actual temperature. (Based on image from http://www.freestylephoto.biz/camerakh.php, accessed 28.02.2010).

Our eyes adjust to these varying color temperatures automatically. Indoor settings for cameras are usually set at 3200K, whereas outdoor settings are usually at 5600K; both of these numbers are averages for indoor tungsten lighting and outdoor daylight. Even though cameras have automatic white balance systems, the white balance setting of your camera allows you to adjust the setting manually. You may set your camera to manual mode and adjust it with a white or gray card. The Canon 5D and 7D, as well as the Panasonic Lumix GH1, include preset color temperatures you can select with the dial (Philip Bloom refers to this as “dialing in the color temperature”). Balancing correctly is important so that you can control your image. Sometimes you may want to experiment with color temperature as a way to change the look of the scene, but you should always control this important element of lighting (see Figure 2.12).

FIGURE 2.12 Three shots of the same model using three different color temperatures. The middle one is “correct.” The first one is too blue, and the third is too warm for the standard look. However, the color temperature is a guide; you may decide the warm image is the color temperature you’re looking for to capture the feeling of your story.

(Photos by Kurt Lancaster.)

Cinematographer’s Tip

Color Temperature

Shane Hurlbut, ASC

You have to get the in-camera look as close as possible to the final vision for the project. It’s an 8-bit color space, 4-2-0. It is compressed and that color space can be limiting. I find it is the compression that makes it look the closest to film, so embrace it. As a cinematographer, you really need to micromanage the color temperature. If you want a day exterior to feel consistent throughout a day from morning till sunset, you need to start with your color temperature so that it is consistent with that of the sun. In the morning it could be around 3400 degrees. To keep the light looking white and not orange, you will need to set your color temp at 3400 Kelvin. By midday it should be around 5200 to 5500 Kelvin. You repeat the same approach at sunset. We had a sequence in Act of Valor on a dry lake bed that posed for a landing strip in the Horn of Africa. We started before the sun came up and were there until it went behind the Sierra Nevadas at around 7:45pm. I used this micromanaging approach and the image is so consistent. In the final color correction we hardly had to do any manipulation other than dialing in contrast. (Hurlbut, S. (2009, Nov. 9). Collision Conference. Video. <http://shanehurlbut.smugmug.com/Professional/CollisionConference/10137672_ia4ZS#697099091_Bqx5z-A-LB>, accessed 28.05.2010).

In addition, many of these cameras allow you to create presets for the picture look. Several DSLR shooters have mimicked the look of a variety of film stocks to create different looks as well. (See Chapter 4 for details on adjusting color temperature, as well as steps for shaping your picture style.) In addition, post-production color grading allows you to further shape the look of your project (Philip Bloom, for example, uses Magic Bullet software to utilize color grading plug-ins to achieve his looks).

There is no one way to determine color balance. Do you balance for tungsten if you’re indoors near a window, do you just go with the camera’s preset (daylight, indoor, outdoor shade, and so forth), or do you dial it in? You need to look at the image and think about how it relates to the story to best determine what you need. Shane Hurlbut, ASC, dials in his color temperature by eyeballing the monitor or the camera’s LCD screen and getting the look as close as he can get it before turning it over to postproduction. Others suggest using the presets for consistency depending on the lighting type you’re in, and setting manual white balance only when in a mixed lighting setup (halogens, fluorescents, incandescents in one room, for example). The Canon 7D tends to go a little red when shooting indoors with the incandescent setting.

White Balance Tip

Do not manually white balance during a sunrise or sunset because you would be adjusting the nice golden flow into white, and you don’t want to lose the golden glow! During the sunset scene in The Last 3 Minutes, Shane Hurlbut, ASC, dialed in his color temperature at 4700 degrees K (see Figure 2.13).

FIGURE 2.13 Shane Hurlbut, ASC, dialed in the color temperature to 4700 degrees Kelvin for the beach scene from The Last 3 Minutes (featured in Ch. 12).

(©2010 Hurlbut Visuals and The Bandito Brothers. Used with permission.)

SAMPLE LIGHTING SETUPS

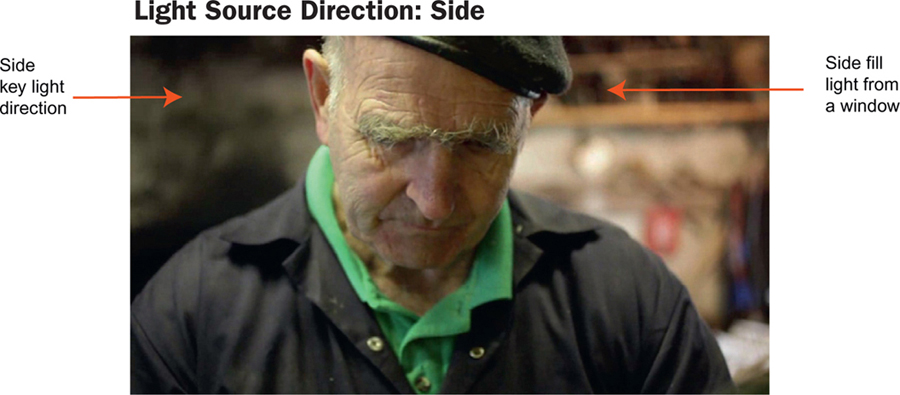

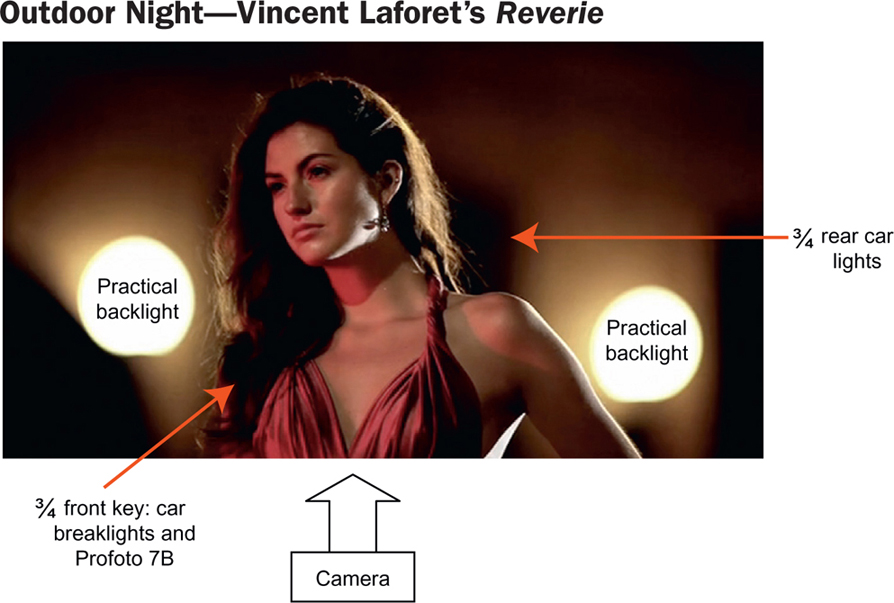

The following stills and diagrams with brief explanations show basic setups for shooting outdoor day, outdoor night, indoor day, and indoor night as tied to the idea of composition and light quality.

Outdoor Day (Soft and Hard)—Philip Bloom’s Cherry Blossom Girl

When shooting outdoor locations, time of day and weather are the two most important factors to consider; they determine your light source and shadows. Big-budget films may use generators with daylight lamps, but when shooting a documentary or an outdoor wedding, for example, you need to be aware of the sun’s location because it will be the primary light source (see Figures 2.14 and 2.15). Mornings and afternoons tend to provide better shooting because the color temperature will provide warmer skin tones; it will also provide long shadows, so you can shape the look around this light and shadow placement. However, when shooting during the “golden hour,” you’ll have less time to shoot and a bit more challenge in post to match the color temps from shot to shot (and sometimes within the shot) because the lighting is changing quickly (and thus the color temperature). In addition, to soften the quality of the light, you may want to use a scrim to remove the harshness of the light on a subject’s face, or you may want to bounce light off a reflector to provide fill light.

Figures 2.14 and 2.15 In these two stills from Philip Bloom’s Cherry Blossom Girl, we see how he utilized the position of the sun to light the same subject in two different ways. In the first, we see the woman lit from the side with soft-quality lighting, reflected sunlight causing fill light on her right side. In the second shot, Bloom places the woman so she’s lit by a high key sun from ¾ back, acting as a hard rim light, which causes a glow around her hair and shoulders. The sunlight reflects back onto her face, acting as a soft fill.

(Stills from Cherry Blossom Girl. ©2009 Philip Bloom. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 2.16 In this shot, Bloom utilizes an open doorway to provide a key light on his two subjects inside. The rear side lighting lights the screen-left side of the couple, while a bit of reflected light on screen right helps add a bit of fill to the scene. Notice the color temperature of warm hues, compared to the cooler tones of the woman in Figures 2.14 and 2.15.

(Still from Cherry Blossom Girl. ©2009 Philip Bloom. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 2.17 In this setup from Laforet’s Reverie, we see a medium close-up of a woman. A ¾ rear key (a kicker provided by car headlights) is used to highlight her hair. The street lights in the background, soft and out of focus, provide some backlighting as well as ambience to the scene. The front left key light with red, projected by car breaklights, is placed ¾ left, along with a Profoto 7B lamp with bare head and reflector; 200mm lens at f/2 wide open. The red light is unmotivated; we don’t see the source of the light in the wider shot.

(Still from Reverie. ©2008 Vincent Laforet. Used with permission.)

Indoor Day—Rii Schroer’s 16 Teeth: Cumbria’s Last Traditional Rakemakers

In shaping the interior during the day, many cinematographers will use windows for short shoots (see Figure 2.18). They may add in a daylight lamp from the direction of the window on longer shoots, so as not to lose light direction when the direction of the light changes over the course of a day.

FIGURE 2.18 Rii Schroer utilizes sunlight from a window as her key light in 16 Teeth: Cumbria’s Last Traditional Rakemakers. The light bounces off the back wall and ceiling, acting as fill light on the characters. A fireplace also adds backlighting screen left. For additional details, see .

(Still from 16 Teeth. ©2009 Rii Schroer. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 2.19 Beauty dish light from above with grid. TV light in front with blue screen. Rim light with bare bulb from behind couch. Lens: 1.2, 85mm at f/2.

(Still from Reverie. ©2008 Vincent Laforet. Used with permission.)

Checklist for Lighting

1. The quality of the light: hard or soft; direct lighting or bounced (or scrimmed) lighting for each light you’re going to use.

2. The kinds of light you’re using: key, fill, back, background. (Yes, there are many different types of lights—from sunlight with a reflector to hardware store halogen work lights, but you need to determine how they’re going to be utilized.) Many scenes will have all four of them, but there’s no rule. Sunlight with a reflector may be all that’s required. With DSLR cameras, Philip Bloom says that he tries to use as much natural and practical light as possible before bringing in other lights. When necessary, he uses LED and Kino Flo Divas, and he stresses the importance of some LED light in front to light the eyes of the performers. But he’s an experienced shooter. If you’re more of a beginner, practice with three-point lighting until you can really “see” the light around you and how you can use it to your advantage and use such material as bouncing light off a white t-shirt, for example.

3. Light placement of each light. A frontal ¾ key will make the scene look different than a rear ¾ key with a frontal fill light. Lighting placement will determine shadow placement, all of which will convey a different mood.

4. Lighting zones or contrast range

A. Will everything be lit evenly?

B. Will there be some contrast between bright and darker areas?

C. Will there be great contrast between the light and shadows?

D. Will you need to scrim the lights to dim them, use a dimmer, move lights closer or farther away from the subject?

E. Do you have shutters on the lights to control where the light falls?

F. Do have blackout scrims (flags) to control where the light and shadows are placed?

5. If you’re shooting outdoors, what time of day will provide the best mood for the scene? Because sunlight is your key light source, it will determine to a large extent the mood of your scene. A high-contrast scene with harsh light might be best during late morning through early afternoon, while early morning or early evening will provide the golden hour look with long shadows and rich sunlight tones. Use of reflectors and scrims will help you control outdoor lighting. Night shots may require additional lighting setups if there aren’t enough practical lights (from storefronts and streetlamps, for example).

6. Control your color temperature. Indoor lighting is different than outdoor lighting. A fluorescent light will look different than an incandescent bulb. Know your primary light source and adjust your white balance accordingly.

NOTE

1 Fauer, J. (2008). Cinematographer Style: The Complete Interviews, Vol. 1. (p.332). American Society of Cinematographers